Abstract

Background

Despite the well-established need for specific measurement instruments to examine the relationship between neighborhood conditions and adolescent well-being outcomes, few studies have developed scales to measure features of the neighborhoods in which adolescents reside. Moreover, measures of neighborhood features may be operationalised differently by adolescents living in different levels of urban/rurality. This has not been addressed in previous studies. The objectives of this study were to: 1) establish instruments to measure adolescent neighborhood features at both the individual and neighborhood level, 2) assess their psychometric and ecometric properties, 3) test for invariance by urban/rurality, and 4) generate neighborhood level scores for use in further analysis.

Methods

Data were from the Scottish 2010 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey, which included an over-sample of rural adolescents. The survey responses of interest came from questions designed to capture different facets of the local area in which each respondent resided. Intermediate data zones were used as proxies for neighborhoods. Internal consistency was evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha. Invariance was examined using confirmatory factor analysis. Multilevel models were used to estimate ecometric properties and generate neighborhood scores.

Results

Two constructs labeled neighborhood social cohesion and neighborhood disorder were identified. Adjustment was made to the originally specified model to improve model fit and measures of invariance. At the individual level, reliability was .760 for social cohesion and .765 for disorder, and between .524 and .571 for both constructs at the neighborhood level. Individuals in rural areas experienced greater neighborhood social cohesion and lower levels of neighborhood disorder compared with those in urban areas.

Conclusion

The scales are appropriate for measuring neighborhood characteristics experienced by adolescents across urban and rural Scotland, and can be used in future studies of neighborhoods and health. However, trade-offs between neighborhood sample size and reliability must be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The impact of neighborhood conditions on health and well-being outcomes has been gaining considerable attention over the past decade [1]. Young people may be especially affected by the neighborhood they live in due to limited mobility restricting each individual’s school, family, and peers to a confined geographic area [2, 3]. Many studies have explored the impact of neighborhood social conditions on adolescent health outcomes including self-rated health (e.g., [2]), alcohol use (e.g., [3]), and violence (e.g., [4]). In line with this increased research interest, there is a need for measurement instruments that examine the features of the neighborhood in order to better understand the relationships between the neighborhood context and adolescent health and well-being [5–7]. Despite this, there are few validated and reliable measures of adolescent neighborhood conditions [6], particularly at the neighborhood level.

Most studies examining neighborhood level conditions make use of structural measures which are based on administrative data such as census information. Recently research has moved beyond examining the structural features of the neighborhood to better understand the societal conditions present at the neighborhood level. Survey data have proven to be a useful source in understanding the social conditions of the neighborhoods in which people reside [5, 8]. However, many studies survey adults to understand the neighborhoods in which the adolescents live, leaving adolescents ignored as active agents within their own neighborhoods [9, 10]. Schaefer-McDaniel [11] argues that this represents a methodological flaw and that adults cannot fully represent with accuracy the experiences and perceptions of young people in their environment. Measures derived from adolescents’ perspectives are therefore considered more theoretically valid than adult measures of the adolescent environment, as young people may have different perceptions of their neighborhood than adults, are exposed to fewer neighborhoods to compare their own with, and access different areas of their neighborhood [12].

Neighborhoods are experienced through an individual’s perceptions and as a collective attribute at an aggregate level (a shared characteristic). Where possible, examining both collective measures and individual perceptions is desirable to allow for the most complete picture of the role of neighborhoods in adolescents’ lives. Kawachi et al. [13] argue that studies examining the relationship between neighborhood social conditions and health should consider both individual perceptions and collective conditions using multilevel frameworks and considering cross-level interactions. For instance, socially isolated individuals may still benefit from residing within a community with positive neighborhood conditions. The construction of valid and reliable measures that operate at both the individual and neighborhood level necessitates an assessment of both psychometric and ecometric properties. Psychometric properties refer to the extent to which items reliably capture a construct at the individual level, while ecometric properties refer to the reliability at the neighborhood level [5]. Although some studies exist detailing the psychometric properties of adolescents’ neighborhood perceptions (e.g., [6]) fewer studies examine the ecometric properties of these measures [12].

An important consideration when deriving neighborhood scales that will be utilized in a variety of neighborhood settings is whether the scale items are operationalized similarly for different types of regions, and what adaptations might be needed to ensure scales are appropriate across neighborhood types. The same scales therefore may not be invariant between urban and rural areas [14]. Neighborhood scales are considered invariant when items within the scale function similarly between different groups (see [15, 16] for a more complete discussion). This makes comparisons between groups justifiable. Two types of invariance are most frequently considered 1) factor loading invariance (metric invariance) and 2) intercept invariance (structural invariance). Metric invariance indicates the factor loadings are equal across groups; if this condition is met, “weak” invariance is satisfied [17]. Reasons metric invariance may not be met include: if respondents from different groups interpret the scale items differently or if certain groups have a higher propensity to extreme responses [16]. Structural invariance indicates that a one-unit change in the item response results in the same change on the underlying factor for both groups. This meets the condition for “strong” invariance [17]. Structural invariance may not be met if certain groups have a different reference point when making statements about themselves, there are differences in social norms, and/or certain groups are prone to respond strongly to an item despite having comparable factor values [16, 18]. Structural invariance implies both the meaning of constructs and levels of the underlying items are the same between groups; thus allowing for group comparisons [19].

This research seeks to construct multi-item scale(s) measuring adolescent’s social environment in the neighborhoods in which they live. Accordingly, both individual and neighborhood measures are derived from adolescent survey data. Psychometric methods are used to validate and measure reliability of individual level measures while ecometric methods are used to measure reliability at the neighborhood level [20]. It is important to have both valid and reliable measurements prior to conducting statistical models using these constructs. Accordingly, the objectives of this research were to: a) establish valid and reliable measures of adolescent neighborhood conditions, b) assess the psychometric and ecometric properties of these measures, c) test for invariance between urban/rural classifications, and d) generate neighborhood level scores that can be used in further analysis.

Methods

Study population, study questionnaire, and data

This research utilizes data from the Scottish 2010 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey, a World Health Organization (WHO) collaborative cross-national study conducted in 44 countries in Europe and North America [21]. The anonymous questionnaire was paper-based and completed in-class under teacher supervision. The data are a nationally representative sample of pupils in Secondary 4 (S4), age approximately 15.5 years, that also includes a boost of rural schools [22] (n = 3591).

Students supplied their residential postcode which was used to determine their location of residence and their urban/rural status. Urbanity was classified into six categories based on the urban-rural postcode classifications by the Scottish Government: 1) 4 cities (settlements with population over, 125,000: Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, and Edinburgh) (n = 620), 2) other urban (other settlements with a population over 10,000) (n = 617), 3) accessible towns (settlements with a population between 3000 and 10,000 and within a 30-min drive time of a settlement of 10,000 or more) (n = 274), 4) remote towns (settlements with a population between 3000 and 10,000 and more than a 30-min drive time of a settlement of 10,000 or more) (n = 247), 5) accessible rural (settlements with a population <3000 and within a 30-min drive time of a settlement of 10,000) (n = 376) & 6) remote rural (settlements with a population <3000 and more than a 30-min drive time of a settlement of 10,000 or more) (n = 456). “Neighborhoods” were represented by Intermediate Data Zones (IDZs). IDZs were developed by the Scottish Government. These zones represent 1235 regions in Scotland, contain on average 4000 residents and are based on administrative data and local knowledge [23].

A set of indicators of neighborhood conditions were previously developed by the HBSC international network, a multinational group of experts in the field of adolescent health (Table 1). Prior to data collection the neighborhood conditions questions were piloted in several countries including Scotland to ensure adolescents understand the meaning of the questions [24]. The goal of many of these indicators was to measure neighborhood social capital specifically for young people drawing on multiple theoretical perspectives [25] and they were based partially on social capital measures used by Kawachi et al. [26] and on qualitative analysis undertaken by Morrow [27]. Other items addressing neighborhood conditions were included in the current analysis regarding neighborhood safety, general perception of neighborhood and presence of certain behaviors and physical features (e.g., rundown buildings). One item regarding the local area was not included in this analysis: “How well off is the area in which you live?” This exclusion was made because this item assessed economic conditions rather than social environment. It did not, therefore, fit theoretically with the other items. These items have been used in multiple past studies either in their entirety, or using a subset (e.g., [28–30]). Items were recoded so that higher values indicated greater presence of each item.

Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis

As a first step exploratory factor analysis was conducted examining the structure of latent variables derived from the items in Table 1. The number of respondents with complete data on all questions of interest was 3396 out of 3591. Two factors were decided on based on the scree plot and the retaining all factors with an eigenvalue of greater than 1.0 [30]. As suggested by Costello and Osborne [31], an oblique rotation was utilized and direct oblimin extraction was conducted by principal axis factoring. Items were retained if they had a factor loading > .40 and did not cross-load on another factor (factor loading > .32, which equates to approximately 10% overlapping variance with other items in that factor) [31, 32]. Psychometric properties of each scale were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient [33].

Confirmatory factor analysis and invariance testing

Secondly, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to determine whether the proposed latent variables exhibit equivalence across urban and rural settings using measurement invariance testing methods. This analysis was limited to a subset of the total sample which included those with valid residential postcode data allowing for classification of residential urban or rural conditions (n = 2590). Those excluded due to missing postcode data had a higher proportion of males compared to those who reported their postcode (53% versus 47%; Chi-Square =10.5; p < .01) but were not significantly different from those who reported their postcode in terms of the HBSC family affluence scale [20].

As noted by Bryne [34], testing for invariance requires a series of hierarchical steps (Table 2). First, a configural model was run (a model where no constraints are placed between groups but the data for all groups are analyzed simultaneously). This model acts as the baseline. Secondly, a metric model was established where factor loadings were constrained to be equal among groups. This assesses metric invariance. Third, a structural model was run where the factor loadings and intercepts are constrained to be equal. This model was compared to the metric model to assess for “strong” invariance. Because there is debate in the literature regarding how best to test for invariance each model is compared to the subsequent model using four tests: 1) a chi-square (X 2) difference test where a nonsignificant value indicates invariance [34], 2) the ratio of the change in X 2 to the change in degrees of freedom between two models (∆X 2/∆df) where a value ≤ 5 indicates invariance [15, 35], 3) the difference in root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and 4) comparative fit index (CFI) values, where a difference ≤0.015 and ≤ .01 respectively indicate invariance [34, 36, 37].

Ecometrics

Ecometric approaches were used to derive neighborhood scores and to test the reliability of the neighborhood measure using linear three-level models [5, 20, 38–40]. The question response is the dependent variable, level one is a categorical variable of the question/item, level two is the individual, and level three is the neighborhood. The reliability of the neighborhood level measure was calculated as a function of the neighborhood variation and the neighborhood sample size. The value is close to 1 when the neighborhood means vary substantially across neighborhoods (holding sample size constant) or the sample size per group is large [41]. Although there is no agreed cut-off for reliability at the neighborhood level, generally scores above 0.60 are considered good or acceptable [42, 43]. Ecometrics mitigates issues associated with using scale means to aggregate to the neighborhood level because it takes individual differences in perceived neighborhood social environment into account by including these as level-two covariates. Measures therefore reflect differences by geographic area rather than respondents’ individual characteristics therefore controlling for possible measurement bias [43]. The residuals are used as the neighborhood variable because they represent what cannot be attributed to individual response patterns with positive values reflecting higher than average levels [39]. It is important to bear in mind that group level coefficients represent a weighted average estimate of each grouping towards the average of the dataset based on group sample size and distance between the group level estimate and the overall estimate, termed “shrinkage,” thus potentially biasing the estimates towards the overall estimate [43]. Although some research refutes the value of the added complexity of ecometrics over simple mean aggregation as the results are similar [44], ecometrics allows for reliability to be calculated which is an important aspect of scale development. Reliability is calculated based on Hox [43].

Individual item responses were imputed prior to ecometric analysis using the person average of available items in each scale, if less than half were missing [45]. Imputation methods on item responses have been used in similar models [46]; alternatively, as stated by Hox [43], the model can accommodate missing data. However, the best approach to missing items in these types of models is still under study [46].

Individuals residing in an area with less than five respondents were excluded. This cut-off is similar to other studies of adolescent neighborhoods [39]. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis where the cut-off was four, as this would allow for additional IDZs to be included in the analyses. Additionally those who were missing data on any of the scale items after imputation (four individuals on each scale had imputation procedures) were excluded, leaving 1491 respondents on the neighborhood disorder scale and 1509 on the social cohesion scale from approximately 190 IDZs for both scales. Those included did not have a significantly higher proportion of males than those not included from the total sample but they were significantly more likely to be in the high family affluence tertile (38% versus 33%). Respondents’ sex was adjusted for in the model as it may influence individual experiences of their neighborhood [39].

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

The scree plot indicated a two-factor solution explaining 42.7% of the variance (34.3% in the 1st factor and 8.4% in the 2nd factor).

Using a two-factor solution, the factors are 1) social cohesion (Items 3, 4, 5, 7), and 2) neighborhood disorder (Items 9, 10, 11). “Perceived good places,” “feeling safe,” and “people would try to take advantage of you” did not load > .4 on either factor while perceiving the local area as good cross-loaded between the two factors (see Table 1). A three-factor solution was also obtained and yielded similar results with the exception that “having good places to spend free time” loaded on its own factor. Given current debate on best methods to determine the number of factors to maintain, we also conducted a parallel analysis with Velicer’s minimum average partial criteria using an R-add on designed for SPSS [44]. The Velicer’s minimum average partial criteria indicated two factors be maintained and the parallel analysis indicated four factors. A four-factor solution produced two non-trivial factors that were similar to the two-factor solution presented earlier. Therefore, a two-factor solution was implemented in the CFA. Cronbach’s alpha for social cohesion was .787 and the alpha for neighborhood disorder was .765.

Confirmatory factor analysis

From the EFA results, a two-factor solution was specified using AMOS software, using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Results of the configural model indicated good model fit (RMSEA = .027, goodness of fit index (GFI) = .975, CFI = .970, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = .951). However, X 2 difference tests indicated non-invariance (difference in X 2 was significant between the configural model and metric model as well as between the metric model and the structural model) while ∆X2/∆df, RMSEA, and CFI difference tests indicated invariance between model comparisons (Table 3). Results of the modification indices were examined and Item 7 (“I could ask for help or favour from a neighbour”) was removed due to high error covariance with other items. Removing this item from the social cohesion scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .760.

After removing Item 7, the six-item configural model indicated improved model fit (RMSEA = .022, GFI = .986, CFI = .986, TLI = .973), meeting the requirement for configural invariance. Additionally criteria for metric invariance were met by all four tests; structural invariance was met using the ∆X2/∆df, RMSEA, and CFI tests (Table 3).Footnote 1

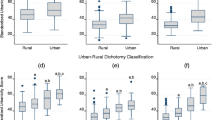

There were significant differences between urban and rural areas on both perceived neighborhood social cohesion and perceived neighborhood disorder found through analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests (Table 4). On average, adolescents in rural areas perceived greater social cohesion and lower neighborhood disorder in their local area; whereas individuals living in accessible small towns perceived the greatest neighborhood disorder.

Ecometrics

The ecometric properties of both neighborhood level social cohesion and neighborhood level disorder are shown below. Both scales showed moderate reliability, but within the range considered acceptable in several other studies, at .577 and .563 respectively [39, 41, 47].

Sensitivity analysis showed that when the cut-off was changed to four individuals per IDZ rather than five per IDZ, the reliability for neighborhood social cohesion and neighborhood disorder dropped to .524 and .543, respectively. However, the number of neighborhoods increased from approximately 190 to 250. Additionally, the number of individual survey respondents increased by approximately 250. Given the substantial increase in neighborhoods and that the reduction in reliability was not great (reliability was still > .50) we proceeded with analysis using the cut-off of four (IDZs n = approximately 250). Moreover, due to the small number of response categories in the neighborhood disorder items, we re-ran the original model as an ordinal three-level model. This also made little difference to reliability (reliability = .589 versus 0.563).

Convergent validity was tested by examining the correlations between neighborhood level constructs and administrative measures available for the IDZs from the Scottish Government [48]. We examined the percent of people living within 500 m of a derelict site in 2010 expecting to find a positive correlation with neighborhood disorder, as well as the estimated percent of working aged households that were materially deprived in 2008/2009 expecting to find a negative correlation with neighborhood social cohesion, as has been found in past studies using adult survey measures [49]. As was expected, neighborhood social cohesion and neighborhood disorder were significantly and negatively correlated (R =−.499, p < .001). Also, a positive correlation was found between proportion of people living near derelict sites and neighborhood disorder (R = .365, p < .001) and a negative association was found with neighborhood social cohesion (R =−.320, p < .001). In terms of material deprivation, a negative correlation was present with neighborhood social cohesion (R =−.396, p < .001) and a positive correlation was found with neighborhood disorder (R = .410, p < .001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to construct neighborhood scales for adolescents at both the individual and neighborhood level that takes into account potential invariance across neighborhood type. Measures across two dimensions of adolescents’ neighborhood social environment were constructed with both yielding good reliability at the individual level and moderate reliability at the neighborhood level. However, it is important to note that the response system varied for the neighborhood questions and that the EFA results largely corresponded with this. Nevertheless, the two measures perform well in CFA.

The research findings of this study are consistent with past research of psychometric and ecometric properties of adolescent neighborhood scales. Studies of rural and urban United States adolescents found similar individual level reliabilities. For example, a measure of neighborhood attachment that used some similar indicators to this study reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .72 [50] and a measure of neighborhood deterioration using comparable measures reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .75 [4]. Additionally, findings are consistent with a study of neighborhood level social capital in Dutch adolescents which found what the authors deem acceptable levels of neighborhood social capital at .57 [39].

We found that adjustments to the originally specified model improved model fit and measures of invariance. The results of invariance testing indicate “weak” (metric) invariance between different urban/rural locations for the six-item model was certainly met. There is also evidence of “strong” (structural) invariance, however, these results are more sensitive to estimation procedure and invariance test used and therefore should be interpreted with caution. Issues with X 2 difference test have been widely noted as it is sensitive to sample size [15, 34, 36]. Therefore the other approaches used to test for invariance may be more appropriate and we can be reasonably confident that strong invariance is met.

Regarding the ecometric analysis, we were able to construct measures that reflect collective attributes that showed moderate reliability. Trade-offs between neighborhood sample size and reliability had to be considered as reliability decreases as a function of within neighborhood sample size. There is no established cut-offs for reliability in ecometric analysis and so the researcher must consider the trade-off between sample size and reliability as well as the purpose of the scales prior to use in future analysis. Estimates of convergent validity were as expected indicating that valid measures of the neighborhood level social environment can be constructed using survey data from adolescents. This is similar to findings based on surveys of adults [5].

A potential limitation of the current study is that an administrative definition was used as a proxy of neighborhoods. The IDZs were constructed with consultation from those with local knowledge (by consultation with Community Planning Partnerships who coordinated the views of local people and regional officials); however, these partnerships are administratively based and therefore do not necessarily include adolescents. Additionally, the questions in the HBSC survey asked adolescents about their “local area” in which they lived but did not specify how local area should be defined and we were unable to determine how the administrative boundaries relate to the adolescents’ perceptions of their local area boundaries. This may contribute to within neighborhood variability [5]. Despite these limitations, IDZs reflect a neighborhood definition for which other data from government sources can be linked.

Another consideration when interpreting the results is the potential for bias due to the presence of missing cases; particularly the proportion who were missing due to non-reporting of postcode data and missing data due to a low number of respondents within neighborhoods. This is a common issue in studies that collect neighborhood data but are not able to target at the neighborhood level, such as in school-based surveys (e.g., [47]).

Although the measures established in this research are suitable for individuals experiencing urban and rural conditions in Scotland they may not be invariant cross-culturally. Further studies are needed to better understand how perceptions of neighborhoods may vary between countries. This represents an important avenue for future research of neighborhood characteristics. Additionally, the compromise between reliability, sample size, and having an appropriate number of respondents per neighborhood is an important area for future research.

Conclusions

It is important that studies examining adolescent outcomes make clear whether associations are found at the individual or collective level as these indicate distinct levels at which to target potential policies and interventions, e.g., people or places [12, 51, 52]. Constructing valid and reliable measures at these different levels represents a crucial first step in understanding the ways in which adolescents experience their local areas. The two scales established in this study can be used to investigate the effect of neighborhood environmental characteristics, specifically social cohesion and neighborhood disorder, on a range of outcomes and from a population health perspective. By accessing adolescent’s own perceptions of the area in which they live, these instruments represent a more useful and appropriate means to measure the impact of neighborhood on adolescent outcomes than many existing measures which are mainly based on adult perceptions or structural indicators.

Notes

Ad hoc tests for multivariate normality were conducted for each urban/rurality type. Overall, the Mardia’s coefficient of multivariate kurtosis suggests non-normality in the sample (range: 4.65–15.35) [34]. Given this, additional models were conducted with asymptotically distribution-free (ADF) estimation (also known as weighted least squares). ADF does not require normality but studies have shown it is only useful for relatively simple models with a moderate to large sample size (some suggest n > 1000) [53–55]. Results were similar to ML estimation but the difference in CFI between the metric model and structural model was -.012.

The majority of studies of invariance testing procedures have been undertaken using ML estimation. Also, there are no standards on appropriate tests and cut-offs for alternative estimation methods. There is some indication that ΔRMSEA performs well with ordinal data [56, 57].

Abbreviations

- ADF:

-

Asymptotically Distribution-free

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- DF:

-

Degrees of freedom

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- GFI:

-

Goodness of fit index

- HBSC:

-

Health Behaviour of School Aged Children

- IDZ:

-

Intermediate Data Zones

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- S4:

-

Secondary 4

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis Index

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Piccolo RS, Duncan DT, Pearce N, McKinlay JB. The role of neighborhood characteristics in racial/ethnic disparities in type 2 diabetes: results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:79–90.

Aminzadeh K, Denny S, Utter J, Milfont TL, Ameratunga S, Teevale T, Clark T. Neighbourhood social capital and adolescent self-reported wellbeing in New Zealand: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:13–21.

Åslund C, Nilsson KW. Social capital in relation to alcohol consumption, smoking, and illicit drug use among adolescents: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:1–11.

Vowell PR. A partial test of an integrative control model: neighborhood context, social control, self-control, and youth violent behavior. Western Criminol Rev. 2007;8:1–15.

Friche AAL, Diez-Roux AV, César CC, Xavier CC, Proietti FA, Caiaffa WT. Assessing the psychometric and ecometric properties of neighborhood scales in developing countries: Saude em Beaga Study, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2008–2009. J Urban Health. 2013;90:246–61.

Oliva A, Antolín L, López AM. Development and validation of a scale for the measurement of adolescents’ developmental assets in the neighborhood. Social Indic Res. 2012;106:563–76.

Moore S, Bockenholt U, Daniel M, Frohlich K, Kestens Y, Richard L. Social capital and core network ties: a validation study of individual-level social capital measures and their association with extra-and intra-neighborhood ties, and self-rated health. Health Place. 2011;17:536–44.

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing“neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;8:443–78.

Morrow V. Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well‐being of children and young people: a critical review. Sociol Rev. 1999;47:744–65.

Paiva PCP, de Paiva HN, de Oliveira Filho PM, Lamounier JA, e Ferreira EF, Ferreira RC, Kawachi I, Zarzar PM. Development and validation of a social capital questionnaire for adolescent students (SCQ-AS). PloS One. 2014;9:DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103785.

Schaefer-McDaniel NJ. Conceptualizing social capital among young people: Towards a new theory. Children Youth Environm. 2004;14:153–72.

Martin G, Gavine A, Inchley J, Currie C. Conceptualizing, measuring and evaluating constructs of the adolescent neighbourhood social environment: A systematic review. SSM-Population Health, 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.03.002.

Kawachi I, Kim D, Coutts A, Subramanian S. Commentary: Reconciling the three accounts of social capital. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:682–90.

Evenson KR, Sotres-Alvarez D, Herring AH, Messer L, Laraia BA, Rodríguez DA. Assessing urban and rural neighborhood characteristics using audit and GIS data: derivation and reliability of constructs. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:DOI: 10.1186/1479-5868-1186-1144.

Choi Y, Harachi TW, Catalano RF. Neighborhoods, family, and substance use: Comparisons of the relations across racial and ethnic groups. Soc Serv Rev. 2006;80:675–704.

Karcher MJ, Sass D. A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. J Couns Psychol. 2010;57:274–89.

Tucker KL, Ozer DJ, Lyubomirsky S, Boehm JK. Testing for measurement invariance in the satisfaction with life scale: A comparison of Russians and North Americans. Social Indic Res. 2006;78:341–60.

Chen FF. What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:1005–18.

Van de Schoot R, Lugtig P, Hox J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2012;9:486–92.

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol. 1999;29:1–41.

Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, Currie D, De Looze M, Roberts C, Samdal O, Smith O, Barnekow V. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people: HBSC international report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 6); 2012.

Levin KA, Dundas R, Miller M, McCartney G. Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in adolescent smoking: a multilevel cross-sectional study of 15 year olds in Scotland. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107:162–70.

Flowerdew R, Feng Z. Scottish Neighbourhood Statistics: Intermediate Geography Background Information. 2005. http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2005/02/20732/53084. Accessed 4 May 2016.

Currie C, Samdal O, Boyce W, Smith B. Health Behaviour in Scholl-Aged Childres: a World Health Organization Cross-National Study Reseaarch Protocol for the 2001/2002 Survey. Scotland: University of Edinburgh; 2001.

Morgan A. Social capital as a health asset for young people’s health and wellbeing: definitions, measurement and theory. Solna: Karolinska Institutet; 2011.

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1491–8.

Morrow V. Young people’s explanations and experiences of social exclusion: retrieving Bourdieu’s concept of social capital. Int J Sociol Social Policy. 2001;21:37–63.

De Clercq B, Vyncke V, Hublet A, Elgar FJ, Ravens-Sieberer U, Currie C, Hooghe M, Ieven A, Maes L. Social capital and social inequality in adolescents’ health in 601 Flemish communities: A multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:202–10.

Vafaei A, Pickett W, Alvarado BE. Neighbourhood environment factors and the occurrence of injuries in Canadian adolescents: a validation study and exploration of structural confounding. BMJ Open. 2014;4:doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004919.

Nichol M, Janssen I, Pickett W. Associations between neighborhood safety, availability of recreational facilities, and adolescent physical activity among Canadian youth. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:442–50.

Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Pract Assessment Res Eval. 2005;10. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v10n7.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2017.

Fields A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 2005.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Rosay AB, Gottfredson DC, Armstrong TA, Harmon MA. Invariance of measures of prevention program effectiveness: A replication. J Quant Criminol. 2000;16:341–67.

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equation Model. 2002;9:233–55.

Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equation Model. 2007;14:464–504.

Fone DL, Farewell DM, Dunstan FD. An ecometric analysis of neighbourhood cohesion. Popul Health Metrics. 2006;4:DOI: 10.1186/1478-7954-1184-1117.

Prins RG, Mohnen SM, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Oenema A. Are neighbourhood social capital and availability of sports facilities related to sports participation among Dutch adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:DOI: 10.1186/1479-5868-1189-1190.

Fagan AA, Wright EM, Pinchevsky GM. A multi-level analysis of the impact of neighborhood structural and social factors on adolescent substance use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:180–6.

Mujahid MS, Roux AVD, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:858–67.

Ruijsbroek A, Droomers M, Hardyns W, Groenewegen PP, Stronks K. The interplay between neighbourhood characteristics: The health impact of changes in social cohesion, disorder and unsafety feelings. Health Place. 2016;39:1–8.

Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Mackenbach J, Lakerveld J, Lenthe F, Kawachi I, McKee M, Rutter H, Glonti K, Compernolle S, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Feuillet T. Neighbourhood social capital: measurement issues and associations with health outcomes. Obes Rev. 2016;17:96–107.

Katz MH. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Finch H. Estimation of item response theory parameters in the presence of missing data. J Educ Meas. 2008;45:225–45.

Jackson N, Denny S, Sheridan J, Zhao J, Ameratunga S. The role of neighborhood disadvantage, physical disorder, and collective efficacy in adolescent alcohol use: a multilevel path analysis. Health Place. 2016;41:24–33.

Government S: Official Statistics. Accessed June 15th 2016 from http://statistics.gov.scot/. 2016.

Drukker M, Kaplan C, Feron F, Van Os J. Children’s health-related quality of life, neighbourhood socio-economic deprivation and social capital. A contextual analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:825–41.

Van Gundy KT, Stracuzzi NF, Rebellon CJ, Tucker CJ, Cohn ES. Perceived community cohesion and the stress process in youth. Rural Sociol. 2011;76:293–318.

Poortinga W. Social capital: an individual or collective resource for health? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:292–302.

Gilbert KL, Quinn SC, Goodman RM, Butler J, Wallace JM. A meta-analysis of social capital and health: A case for needed research. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:1385–99.

Finney SJ, DiStefano C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course. United States of America: Information Age Publishing, Inc; 2006. p. 269–314.

Jones JA, Waller NG. The normal-theory and asymptotic distribution-free (ADF) covariance matrix of standardized regression coefficients: theoretical extensions and finite sample behavior. Psychometrika. 2015;80:365–78.

Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol Methods. 2004;9:466–91.

Koziol NA. Evaluating measurement invariance with censored ordinal data: A monte carlo comparison of alternative model estimators and scales of measurement. University of Nebraska, 2010.

Ranøyen I, Stenseng F, Klöckner CA, Wallander J, Jozefiak T. Familial aggregation of anxiety and depression in the community: the role of adolescents’ self-esteem and physical activity level (the HUNT Study). BMC Public Health. 2015;15:DOI: 10.1186/s12889-12015-11431-12880.

Acknowledgments

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study is an international survey conducted in collaboration with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. The authors would like to acknowledge the HBSC international research network that developed the study’s research protocol. For details, see http://www.hbsc.org. Funding for the Scottish Survey was provided by NHS Scotland. This work was also supported by the 600th Anniversary PhD Scholarship which was awarded to Gina Martin by the University of St Andrews.

Additionally, we thank the Regional and Island Authorities for granting permission for their schools to participate in the survey; and all the young people who generously completed questionnaires; and the schools and teachers who kindly agreed to administer the survey.

Funding

This work was supported by NHS Health Scotland and the University of St Andrews. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Availability of data and supporting materials

Data from the Health Behaviours of School-Aged Children Survey are available at http://www.uib.no/en/hbscdata. However, the data used specifically in this study are not publically available due to concerns over participant confidentiality for the reason that geographic variables are used.

Authors’ contributions

GM, CC, and JI conceptualised the study. GM conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript with inputs from JI, CC, and GH. GH provided statistical expertise. CC was the Principal Investigator for the Scottish 2010 Health Behaviour of School- Aged Children Survey. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the University of Edinburgh’s School of Education Ethics Committee. Additionally, ethical approval for use of the data was obtained by the University of St Andrews Teaching and Research Ethics Committee (reference number: MD11023).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, G., Inchley, J., Humphris, G. et al. Assessing the psychometric and ecometric properties of neighborhood scales using adolescent survey data from urban and rural Scotland. Popul Health Metrics 15, 11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-017-0129-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-017-0129-1