Abstract

Background

In South and Southeast Asian countries, tobacco is consumed in diverse forms, and smoking among women is very low. We aimed to provide national estimates of prevalence and social determinants of smoking and smokeless tobacco use among men and women separately.

Methods

Data from Demographic and Health Surveys completed in nine countries (India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, Philippines, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Timor Leste) were analyzed. Current smoking or smokeless tobacco use was assessed as response “yes” to one or more of three questions, such as “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” Weighted country-level prevalence rates for socio-economic subgroups were calculated for smoking and smokeless tobacco use. Binary logistic regression analyses were done on STATA/IC (version 10) by ‘svy’ command.

Results

Prevalence and type of tobacco use among men and women varied across the countries and among socio-economic sub groups. Smoking prevalence was much lower in women than men in all countries. Smoking among men was very high in Indonesia, Maldives, and Bangladesh. Smokeless tobacco (mainly chewable) was used in diverse forms, particularly in India, among both men and women. Chewing tobacco was common in Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Cambodia. Both smoking and smokeless tobacco use were associated with higher age, lower education, and poverty, but their association with place of residence and marital status was not uniform between men and women across the countries.

Conclusion

Policymakers should consider type of tobacco consumption and their differentials among various population subgroups to implement country-specific tobacco control policies and target the vulnerable groups. Smokeless tobacco use should also be prioritized in tobacco control efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2010, globally, 54% of Disability adjusted Life Years (DALYS) were caused from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [1] and tobacco smoking including second-hand smoke was one of the leading risk factors for global disease burden accounting for 6.3% of global DALYS [2]. If the current trend of tobacco use continues, it could cause approximately 8.3 million deaths annually by the year 2030 [3], and more than 80% of them may occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [4], where nearly two-thirds of the world’s smokers live [3]. In 2012, there were an estimated 967 million smokers from 187 countries [5], with the highest burden of tobacco use in high-income countries (HICs), intermediate in middle-income countries, and lowest in low-income countries. The deaths attributable to tobacco use are 18%, 11%, and 4% respectively [6]. Increasing rates of smoking in many LMICs and decreasing rates in HICs may lead to increased proportional tobacco-related mortality in LMICs [6],[7].

The Southeast Asia region is home to nearly 400 million tobacco users, who experience about 1.2 million deaths annually [7]. Although smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is common among women, smoking among women is increasing [8],[9]. In Southeast Asia, tobacco is used in diverse forms, including cigarettes or bidis (dried tobacco rolled in paper or leaf), SLT such as chewing khaini (tobacco with slaked lime and aromatic spices), surti (dried tobacco leaves for chewing), or paan masala (tobacco with aromatic spices), sucking gutkha (mixture of tobacco and molasses available in small sachets), applying gul or gudaku as dentifrice, and inhaling nas and naswar (nasal inhalation of tobacco powder) [10]. Bidis are popular in Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, whereas cheroots are popular in Myanmar, and roll-your-own cigarettes (in palm leaves or paper) are popular in Thailand and Timor Leste. In Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, use of gul, gudaku, mishri, masher, lal dantamanjan as dentrifice, and nas/naswar is common [11]. SLT use in various forms is directly responsible for oropharyngeal cancers [12],[13].

Socio-economic differentials in tobacco use have existed in both developed [14],[15] and developing countries [16]-[18]. Studies have reported that tobacco consumption rates are higher in lower socioeconomic classes and less-educated groups [16],[17],[19]. Moreover, smoking prevalence is lower among women worldwide, particularly in South and Southeast Asia [20]. Therefore, assessing socio-economic differentials of tobacco use in Southeast Asia by population-based surveys will provide information about effectiveness of tobacco control measures and aid policymaking. The global tobacco surveillance system [21], World Health Organization (WHO) STEPS program [22], and WHO World Health Surveys (WHS) [23] have provided such information. However, these surveys cover several countries from various regions, but not all of the countries in a region. Moreover, the literature from these surveys has emphasized smoking and reported determinants of tobacco use [16],[17],[24], but not about SLT use, which is prevalent in South and Southeast Asia [11]. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) collect information about tobacco use in nationally representative samples of men and women and have provided national estimates of tobacco use for Nepal [25], India [26],[27], sub-Saharan Africa [18], and other countries [28]. We aimed to provide national estimates on prevalence and social determinants of tobacco smoking and smokeless tobacco use in South and Southeast Asian countries.

Methods

Data source

We used data from nationally representative samples of women and men from DHSs conducted between 2005–2006 and 2012–2013 in nine South and Southeast Asian countries: India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia, and Timor Leste (Table 1). DHS aims to provide reliable indicators about fertility, family planning, health, and nutrition of populations in developing nations [29],[30]. DHSs were implemented by country-level statistical offices or other local institutions and are technically supported by ORC (Opinion Research Corporation) Macro International Inc. of Calverton, Maryland, USA and financially supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) [30].

Sampling and sample size

The final samples of households in DHSs were selected by two stages, stratified random sampling using population proportionate to size technique to include both rural and urban residents. Heads of each selected household answered general questions about the household and listed the household members. All women aged 15 to 49 years and men aged 15 to 49 years or more (up to 54 years in India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh and up to 64 years in Maldives) who were the usual residents were eligible to participate. Trained interviewers collected information about demographic and socio-economic factors and health status. Questions about tobacco use were asked of all eligible men and women [29],[30], except in Bangladesh and the Philippines (Table 1).

Outcome variables

The following four identical questions were asked to elucidate information about tobacco use in all countries, but response options varied between countries (see below).

-

1)

Do you currently smoke cigarettes? (response as ‘yes’ or ‘no’)

-

2)

In the last 24 hours, how many cigarettes did you smoke? (response as numerical)

-

3)

Do you currently smoke or use any other type of tobacco? (response as ‘yes’ or ‘no’)

-

4)

What (other) type of tobacco do you currently smoke or use? (options provided were pipe, chewing tobacco, snuff, country-specific options, and others)

Additional country-specific options given were the use of hookah (sheesha), bidi, and cigars in Maldives; bidi in India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh; cigars in Philippines; hand-rolled tobacco in Timor Leste; Pan Masala and Gutkha in India; and nuswar in Pakistan. Each respondent was classified as ‘current smoker’ if the response to the first question was ‘yes,’ the response to the fourth question was ‘pipe,’ or if they were using hookah, bidi, cigars, or hand-rolled tobacco. The respondents were classified as ‘current SLT user’ if the response to the fourth question was any form of SLT, including ‘chewing’ tobacco, ‘Pan Masala’, ‘Gutkha,’ and ‘snuff.’

Explanatory variables

Age, religion, and marital status were reclassified for logistic regression analyses. Religion was categorized as Hindu, Islam, Roman Catholic, Buddhist, and others. Each religion was classified into two categories, i.e., main religion of the country and others, except in India (Hindu, Muslim, and others). Age of the participant was recoded as 15–29, 30–39, and 40-49/≥40 years (for women and men, respectively). Marital status was classified as being married or single. Single constituted being never married, separated, or divorced. A cohabiting partner was included under single as its proportion was very small in most countries. In DHS, place of residence was classified as rural or urban; educational level was classified as ‘no education’, ‘primary’, ‘secondary,’ or ‘higher.’ Household wealth index, considered a reliable proxy for household economic status [31], was calculated based on a standard set of household assets, dwelling characteristics, and ownership of consumer items as observed by the interviewer. Participants were ranked on the basis of their household score by dividing them into quintiles where the first quintile was the poorest 20% of the households and the fifth quintile was the wealthiest 20% [32].

Ethics statement

The institutional review boards of ORC Macro International Inc. and participating institutions in each country provided ethical clearance for DHSs. In each survey, participants were informed about voluntary participation and confidentiality of information and could refrain from responding to any of the questions. Before each interview, details of the survey were explained and informed consent was obtained. Written consent was not obtained since no intervention was applied to the participants.

Data analysis

All analyses were done for men and women separately in each country. Descriptive analyses were done for smoking and SLT use. Overall weighted prevalence estimates for tobacco smoking and SLT use were calculated by including sample weights to account for the complex sampling design of DHS. Weighted prevalence estimates of smoking and SLT use were calculated according to age groups, religion, place of residence, marital status, education, and wealth quintiles. Binary logistic regression analyses were done to assess demographic (age was entered as continuous variable) and socio-economic factors associated with smoking and SLT use by SVY command on STATA/IC version 10 [33]. Beta-coefficients, their 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were calculated.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample size of women interviewed was greater than for men since DHS mainly aimed to estimate indicators related to mother and child health (Table 1). In the 2008 Philippines DHS, men were not sampled, whereas in 2007 Bangladesh DHS, women were not asked about tobacco use. In Pakistan, Indonesia, and Maldives, information about religion was not collected (Table 2). Both men and women were mainly from rural areas in Maldives, Cambodia, Nepal, and Timor Leste, whereas in India, Pakistan, and Indonesia urban–rural distribution was nearly equal. More than half of men and women were aged between 15 and 29 years in all countries except Bangladesh, Maldives, and Indonesia, where about 45% of men were aged ≥40 years. Most participants were educated through primary and secondary level, except in the Philippines, where a third of women had received higher education. Nearly a third of men were uneducated in Bangladesh and Maldives. A high proportion of women (56.2% to 17.1%) were not educated in all countries except Indonesia (3.6%) and the Philippines (1.6%). Two-thirds or more of both men and women were married, but in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, and Indonesia ≥95% of men were married. Participants were evenly distributed across all wealth quintiles except in Maldives, Indonesia, and Timor Leste where the richest quintile was the smallest.

Prevalence of smoking and SLT use

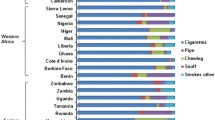

Among men, weighted prevalence of smoking varied between the countries; the highest prevalence was found in Indonesia (72.3%), followed by Timor Leste (69.5%), Bangladesh (60.0%), and Maldives (47.3%), but prevalence was lower in India (34.1%), Nepal (33.6%), Cambodia (34.7%), and Pakistan (31.6%). Prevalence of SLT use among men also varied between countries, with the highest prevalence in India (36.7%), followed by Nepal (34.8%) and Bangladesh (21.4%), and the lowest in Indonesia (0.46%) and Timor Leste (2.5%) (Figure 1). Among women, weighted prevalence of smoking was much lower than men in all countries; the highest prevalence was in Nepal (9.8%), followed by Philippines (5.2%), Maldives (4.6%), and Pakistan (4.02%). Prevalence of SLT use among women was highest in India (9.0%), followed by Cambodia (5.1%), Nepal (4.8%), and Maldives (4.2%) (Figure 1). The most common form of tobacco consumed was cigarettes in all countries except India and Timor Leste. Cigarettes/bidis were smoked in India, and hand-rolled cigarettes were smoked in Timor Leste. However, Indian men and women used diverse forms of SLT including ‘gutkha,’ ‘pan masala,’ and other chewing tobacco (unspecified). Chewing tobacco was also common in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Cambodia. Indonesian men mostly smoked cigarettes, while women there were also using chewing tobacco. Smoking a pipe/cigar was only seen among Filipino and Nepalese women, while women from Maldives and Pakistan mostly smoked hookah (Figure 2).

Prevalence of smoking and SLT use according to socio-economic and demographic factors

Differentials in smoking and SLT use according to socio-economic and demographic variables are shown separately for men and women in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Prevalence of both smoking and SLT use among men was higher in rural areas than urban areas in all countries (for example, among Indian men 36.8 vs. 29.5 and 39.9 vs. 31.3, respectively). Smoking and SLT use among women was higher in rural areas in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Cambodia, but these differentials varied for prevalence of smoking and SLT use among women in other countries. Prevalence of smoking and SLT use among both men and women varied according to wealth quintiles and educational level. In all countries among men and women, prevalence of smoking and SLT use was generally highest among the least educated and the lowest among those with higher education. Prevalence of tobacco use was highest among the poorest and lowest among the richest. For example, among Nepalese men, prevalence rates for smoking and SLT use in those with no education vs. the highest education was 57.9 vs. 20.5 and 57.8 vs. 18.4, respectively. Among Bangladeshi men prevalence rates for smoking and SLT use in the poorest group vs. the richest was 70.1 vs. 46.8 and 26.6 vs. 15.7, respectively. The only exception was seen in Maldivian men, where differentials were very small for prevalence of smoking (poorest vs. richest was 47.6 vs. 52.9) (Table 3). Prevalence of both smoking and SLT use was higher among married men and women in all countries except the Philippines, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Maldives. Prevalence of both smoking and SLT use was higher among men and women aged ≥40 years in all countries, except for smoking among men and women in Maldives and SLT use among Pakistani and Indonesian men. Among Indian, Pakistani, Nepalese, and Maldivian women differentials by age were very high. For example, among Maldivian women, prevalence of smoking and SLT use in the 15–29 age group vs. those 40–49 years old was 1.1 vs. 10.4 and 0.2 vs.10.6, respectively (Table 4).

Association of tobacco use with socio-economic and demographic factors

The association of tobacco use among men and women with socio-economic and demographic factors was assessed using binary logistic regression analysis. Men from rural areas had greater likelihood of smoking and SLT use in India only. Women from rural areas had greater likelihood of smoking in all countries except Nepal and Cambodia and SLT use in India, Cambodia, and Timor Leste (Table 5). Older men were more likely to smoke and use SLT in most countries (except for SLT use in Indonesia and Timor Leste). Older men were less likely to smoke in Maldives (β = −0.03) and Indonesia (β = −0.01).Older women were more likely to smoke and use SLT in all countries (β coefficients ranged from 0.04 to 0.12, Table 5). Married men were more likely to smoke and use SLT in all countries except Bangladesh (for both smoking and SLT use), Maldives, Indonesia, Cambodia, and Timor Leste (for SLT use only). Married women were more likely to smoke in the Philippines but were less likely to smoke in Indonesia and Maldives. Married women were more likely to use SLT in Nepal only (Table 5). Smoking and SLT use among both men and women were strongly associated with education (protective effect) in all countries, except for SLT use among men from Bangladesh and Timor Leste. Individuals who were educated were less likely to smoke or use SLT. Smoking and SLT use among men was associated with wealth in all countries except Nepal, Pakistan, Timor Leste, and Maldives, while the association of wealth with smoking and SLT use among women was seen in all countries except Timor Leste (for smoking). Wealthier individuals were less likely to smoke or use SLT. Smoking among men was associated with religion in India, Nepal, Cambodia, and Timor Leste, while SLT use among men was associated with religion in India and Nepal. Smoking among women was associated with religion in India, Philippines, and Cambodia, while SLT use among women was associated with religion in India and Nepal (data about religion was not collected in Indonesia and Maldives).

Discussion

Our report using DHS datasets provided national-level estimates and information about the pattern of tobacco use in nine countries in the South and Southeast Asia region. Our disaggregated analyses by gender and type of tobacco use demonstrated that pattern of tobacco consumption has cross-country and intracountry variations. In each country, tobacco consumption among men and women was unequally distributed in all demographic and socio-economic groups. Tobacco use among women was very low in all countries, but smoking was higher in Nepal and SLT use higher in India than other countries. Prevalence of smoking and SLT use among men was almost equal in India and Nepal, but among Bangladeshi men, smoking was higher than SLT use. Prevalence of smoking among men was very high in Indonesia, Timor Leste, and Maldives while SLT use was very low. In all countries, significant associations between age, education, and wealth for both smoking and SLT use highlights the existence of social disparities in tobacco use.

Prevalence estimates were comparable to DHS-based estimates for India [26] and Nepal [25] and were much higher than estimates for India and Nepal in GATS [17],[34], but prevalence in Cambodia was lower compared to another national survey [35]. Only three (India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines) of the nine countries that had also participated in the first wave of GATS did not allow comparison of prevalence in all GATS countries [17],[34]. Moreover, our estimates cannot be compared with those of GATS and WHS, which defined current smoking as smoking of any form of tobacco either daily or occasionally [16],[34], while the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study defined daily smoking as smoking any type of tobacco product at least once per day [5]. Our estimates for the current smoking rate among men in Indonesia and Timor Leste were approximately 70%, whereas GBD reported rates as <61%. Similarly, among Nepalese women, our estimate for current smoking was 10%, but GBD results put daily smoking rate at 17%. Differences as large as these between our estimates and those from GBD may have occurred due to differences in data sources, definition of smoking, and statistical methods used for estimating prevalence rates [5]. GBD used multiple sources of microdata and aggregate data from major multicountry survey programs such as DHS, GATS, WHS, WHO STEPwise Approach to Surveillance program, and others, national-level, multiyear surveys on health, addiction, and risk factors, and three large health databases. To estimate prevalence of daily smoking, GBD analyzed data from the sources listed above for 2,102 country-years from 181 countries for a 33-year period, while we used cross-sectional samples of men and women from one DHS in each of the nine South and Southeast Asian countries for 2005–2013. GBD defined a daily smoker as someone who smokes any type of tobacco product at least once per day, but we defined current smoker as someone who responded as “yes” to the question, “Do you currently smoke cigarette?”. Moreover, GBD adopted robust statistical techniques such as regression analyses to adjust for data providing varying or non-standard definitions for smoking, but we relied on participants’ response to three questions to define current smokers. GBD estimates are more realistic, as the study used a spatial-temporal regression model and Gaussian process regression to create a complete time-series for all data from multiple sources, followed by computation of age-standardized prevalence rates, while our study computed the weighted point prevalence of current smoking among men and women, which was not age-standardized. Such methodological heterogeneity of tobacco surveys and the importance of more systematic design of surveys, questionnaires, and definitions have been previously underscored [25],[26]. Comparison with DHS-based reports for India and Nepal shows an increase in prevalence of tobacco use [25],[26]. Low prevalence of smoking and SLT use among women as reported earlier [17],[34] is not surprising since it is socially unacceptable for women to smoke in South Asian communities [36]. However, SLT use was common in India, Nepal, and Cambodia, confirming the results of previous studies [11],[37].

Our findings that current smoking is prevalent from the age of 15 years onwards but was higher in older age groups which is similar to results of previous surveys [16]-[18],[34]. This may be due to a cohort effect (i.e., smoking was less likely to be initiated in more recent decades). This means that more attention should be paid to young men in Indonesia, Maldives, and Bangladesh, where prevalence rates of smoking were alarmingly high. Some think that tobacco companies have been aggressively marketing to young people in these countries, particularly in Indonesia [38]. A protective effect of education on smoking, after controlling for other factors, was consistent with results of previous studies [16]-[18]. However, association of smoking with wealth index was consistent for women in most countries, but not for men, highlighting that smoking behavior may be context-specific, needing country-level analysis like that seen in the GATS report [17] but not in other reports from WHS [16] and DHS [18]. In developed countries, the smoking epidemic began among the rich and educated and later spread to lower socio-economic groups [39], but in developing countries the less educated may have taken up smoking, due to lack of awareness about health risks [40]. Lack of association of wealth index with smoking in some countries could be explained by parental influences, peer pressure [41], and cultural acceptance of smoking [42]. Significantly higher rates of smoking among urban residents have been reported [18],[43]; in our study a higher prevalence of tobacco use among rural residents was not significant for men (with multivariate analysis). We found that socio-demographic factors associated with SLT use were increasing age, lower education, and poverty among both men and women, which is similar to determinants of current smoking in our study and studies from India [26], Nepal [25], and Bangladesh [44], which analyzed SLT use separately. These findings are also similar to multicountry surveys that reported social determinants of tobacco use [17] or smoking only [16],[18].

An advantage of using DHS data was that DHS included large representative samples of men and women and allowed cross-country comparison of tobacco prevalence. Our analysis has revealed, albeit with some limitations, that comparable estimates of current tobacco use can be obtained from DHS. However, future DHS in more than 85 LMICs should include more questions about previous tobacco use and quit attempts to provide data for monitoring of the global tobacco epidemic [45],[46]. Although GATS intends to include more countries [34] in future surveys, DHS cover most LMICs [30] where the majority of tobacco-attributable deaths occur [4]. Our analysis fulfills the need for assessing the social disparities in tobacco use [24],[42] and studying the pattern of tobacco use [26] in South and Southeast Asia, which already has a high burden of communicable and nutrition-related diseases [47]. Urgent actions are necessary to reduce the burden of NCDs [48]. If nothing is done, health inequalities health among the socially disadvantaged may widen further.

There are some limitations of estimates from DHS data due to its design and the questions asked about tobacco use. First, the sample of men and women aged 15–49 years leads to under-estimation, if men and women aged >49 years had higher rates of tobacco use. Second, from the limited questions asked we could only estimate current use, unlike WHS and GATS, which have provided insights into other stages of smoking behavior such as never user and former user. Third, participants were asked to quantify tobacco use by cigarettes smoked during the last 24 hours, but other forms of smoking (bidi, pipe, hookah) and SLT use were not quantified. Fourth, the associations with social factors lack temporal relationships, as DHS were cross-sectional studies. Lastly, in conservative Asian societies it is very likely that tobacco use based on self-report may be under-reported, and DHS did not verify this by measuring urinary cotinine levels.

Conclusions

Our study provides information about prevalence and patterns of tobacco use among men and women in South and Southeast Asian countries not covered in other multicounty surveys and confirms that tobacco use was higher among men, the less educated, and the poor, particularly those living in rural areas. Policymakers should consider the diverse forms of tobacco used and social distribution in each country to provide context-specific tobacco prevention and control strategies and target vulnerable groups. Policymakers need to consider SLT use separately in tobacco control efforts, since the economic and health effects of SLT use are different from that of smoking.

References

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, et al.: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380: 2197-2223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, et al.: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380: 2224-2260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8

Detels R, Beaglehole R, Lansang MA, Gulliford M: Oxford Textbook of Public Health. Oxford University Press, New York; 2011.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD: Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet 2003, 362: 847-852. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3

Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Wollum A, Sanman E, Wulf S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Gakidou E: Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012. JAMA 2014, 311: 183-192. 10.1001/jama.2013.284692

Mathers C, Stevens G, Mascarenhas M: Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2009.

WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011: Warning About the Dangers of Tobacco. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2011.

Sinha DN, Palipudi KM, Rolle I, Asma S, Rinchen S: Tobacco use among youth and adults in member countries of South-East Asia region: review of findings from surveys under the Global Tobacco Surveillance System. Indian J Public Health 2011, 55: 169. 10.4103/0019-557X.89946

Thakur JS, Garg R, Narain JP, Menabde N: Tobacco use: a major risk factor for non communicable diseases in South-East Asia region. Indian J Public Health 2011, 55: 155. 10.4103/0019-557X.89943

Kyaing NN, Islam MA, Sinha DN, Rinchen S: Social, economic and legal dimensions of tobacco and its control in South-East Asia region. Indian J Public Health 2011, 55: 161. 10.4103/0019-557X.89944

Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Ray CS, Singh PK: Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among adults in WHO South-East Asia. Indian J Cancer 2012, 49: 342. 10.4103/0019-509X.107726

Boffetta P, Hecht S, Gray N, Gupta P, Straif K: Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol 2008, 9: 667-675. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70173-6

Gupta PC, Ray CS: Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirology 2003, 8: 419-431. 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x

Barbeau EM, Leavy-Sperounis A, Balbach ED: Smoking, social class, and gender: what can public health learn from the tobacco industry about disparities in smoking? Tob Control 2004, 13: 115-120. 10.1136/tc.2003.006098

Jarvis MJ, Wardle J: Social patterning of individual health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. Edited by Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Hosseinpoor AR, Parker LA, d’Espaignet ET, Chatterji S: Socioeconomic inequality in smoking in low-income and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. PLoS One 2012, 7: e42843. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042843

Palipudi KM, Gupta PC, Sinha DN, Andes LJ, Asma S, McAfee T: Social determinants of health and tobacco use in thirteen low and middle income countries: evidence from Global Adult Tobacco Survey. PLoS One 2012, 7: e33466. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033466

Pampel F: Tobacco use in sub-Sahara Africa: estimates from the demographic health surveys. Soc Sci Med 2008, 66: 1772-1783. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.003

Mathur C, Stigler MH, Perry CL, Arora M, Reddy KS: Differences in prevalence of tobacco use among Indian urban youth: the role of socioeconomic status. Nicotine Tob Res 2008, 10: 109-116. 10.1080/14622200701767779

Mackay J, Amos A: Women and tobacco. Respirology 2003, 8: 123-130. 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00464.x

Warren CW, Asma S, Lee J, Lea V, Mackay J: Global tobacco surveillance system. The GTSS atlas Atlanta, Georgia, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009, 9: 9.

Bonita R, De C, Dwyer T, Jamrozik K, Winkelmann R: The WHO Stepwise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS) of NCD Risk Faktors. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2001.

Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Mechbal A, Murray CJ: The World Health Surveys. In Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism. World Health Organization, Geneva; 2003:797.

Harper S, McKinnon B: Global socioeconomic inequalities in tobacco use: internationally comparable estimates from the World Health Surveys. Cancer Causes Control 2012, 23: 11-25. 10.1007/s10552-012-9901-5

Sreeramareddy CT, Ramakrishnareddy N, Harsha KH, Sathian B, Arokiasamy JT: Prevalence, distribution and correlates of tobacco smoking and chewing in Nepal: a secondary data analysis of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey-2006. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2011, 6: 33. 10.1186/1747-597X-6-33

Rani M, Bonu S, Jha P, Nguyen SN, Jamjoum L: Tobacco use in India: prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey. Tob Control 2003, 12: e4. 10.1136/tc.12.4.e4

Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Kelly M, Gordon D, Smith GD: Patterns and distribution of tobacco consumption in India: cross sectional multilevel evidence from the 1998–9 national family health survey. BMJ 2004, 328: 801-806. 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.801

Ansara DL, Fred A, Sunita K, Jason H, Rachel K: Tobacco use by men and Women in 49 Countries With Demographic and Health Surveys: DHS Comparative Reports. 31. ICF International, Calverton, Maryland, USA; 2014.

Demographic and Health Surveys. ICF Macro, Calverton, MD; 2009.

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV: Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol 2012, 41: 1602-1613. 10.1093/ije/dys184

Rutstein SO, Johnson K: Demographic and Health Survey Wealth Index. ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS, Calverton, MD; 2004.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L: Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan 2006, 21: 459-468. 10.1093/heapol/czl029

StataCorp LP: Stata/IC 10, 0 for Windows. College Station, Texas; 2007.

Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, Gupta PC, Jarvis MJ, Bhala N, Peto R, Zatonski W, Hsia J, Morton J, Palipudi KM, Asma S: Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet 2012, 380: 668-679. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61085-X

Singh PN, Yel D, Sin S, Khieng S, Lopez J, Job J, Ferry L, Knutsen S: Tobacco use among adults in Cambodia: evidence for a tobacco epidemic among women. Bull World Health Organ 2009, 87: 905-912. 10.2471/BLT.08.058917

Toll BA, Ling PM: The Virginia Slims identity crisis: an inside look at tobacco industry marketing to women. Tob Control 2005, 14: 172-180. 10.1136/tc.2004.008953

Sinha DN, Bajracharya B, Khadka BB, Rinchen S, Bhattad VB, Singh PK: Smokeless tobacco use in Nepal. Indian J Cancer 2012, 49: 352-356. 10.4103/0019-509X.107728

Webster PC: Indonesia: the tobacco industry’s“Disneyland”. CMAJ 2013, 185: E97-E98. 10.1503/cmaj.109-4342

Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T: A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control 1994, 3: 242. 10.1136/tc.3.3.242

Siahpush M, McNeill A, Hammond D, Fong GT: Socioeconomic and country variations in knowledge of health risks of tobacco smoking and toxic constituents of smoke: results from the 2002 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006, 15: iii65-iii70.

Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, Crump AD, Eitel P, Saylor KE: Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Educ Behav 2001, 28: 95-107. 10.1177/109019810102800109

David A, Esson K, Perucic AM, Fitzpatrick C: Tobacco use: equity and social determinants. Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes 2010, 199.

Völzke H, Neuhauser H, Moebus S, Baumert J, Berger K, Stang A, Ellert U, Werner A, Döring A: Urban–rural disparities in smoking behaviour in Germany. BMC Public Health 2006, 6: 146. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-146

Palipudi KM, Sinha DN, Choudhury S, Zaman MM, Asma S, Andes L, Dube S: Predictors of tobacco smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults in Bangladesh. Indian J Cancer 2012, 49: 387-392. 10.4103/0019-509X.107745

Warren CW, Asma S, Lee J, Lea V, Mackay J: Global tobacco surveillance system. The GTSS Atlas Atlanta, Georgia, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009.

Giovino GA, Biener L, Hartman AM, Marcus SE, Schooley MW, Pechacek TF, Vallone D: Monitoring the tobacco use epidemic I. Overview: optimizing measurement to facilitate change. Prev Med 2009, 48: S4-S10. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.08.007

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, et al.: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380: 2095-2128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0

Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, Adams C, Alleyne G, Asaria P, Baugh V, Bekedam H, Billo N, Casswell S, Cecchini M, Colagiuri R, Colagiuri S, Collins T, Ebrahim S, Engelgau M, Galea G, Gaziano T, Geneau R, Haines A, Hospedales J, Jha P, Keeling A, Leeder S, Lincoln P, McKee M, Mackay J, Magnusson R, Moodie R, Mwatsama M, et al.: Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 2011, 377: 1438-1447. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0

Acknowledgments

The authors thank measureDHS for providing us access to data from nine countries of the South and Southeast Asia region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CTS was principal author who conceptualized the manuscript, performed data analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the results and discussion sections of the manuscript. PMS assisted in conceptualization of the manuscript, wrote the background and methods sections, and revised the final drafts of the manuscript. IAM assisted in conceptualization of the manuscript, assisted in data analyses, prepared the tables and graphs, and revised the final draft of the manuscript. SS assisted in conceptualization of the manuscript, assisted in revised data analyses, prepared the revised tables and results section, and revised the initial version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sreeramareddy, C.T., Pradhan, P.M.S., Mir, I.A. et al. Smoking and smokeless tobacco use in nine South and Southeast Asian countries: prevalence estimates and social determinants from Demographic and Health Surveys. Popul Health Metrics 12, 22 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-014-0022-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-014-0022-0