Abstract

Progress has been made in recent years to bring attention to the challenges faced by school-aged girls around managing menstruation in educational settings that lack adequate physical environments and social support in low- and middle-income countries. To enable more synergistic and sustained progress on addressing menstruation-related needs while in school, an effort was undertaken in 2014 to map out a vision, priorities, and a ten-year agenda for transforming girls’ experiences, referred to as Menstrual Hygiene Management in Ten (MHM in Ten). The overarching vision is that girls have the information, support, and enabling school environment for managing menstruation with dignity, safety and comfort by 2024. This requires improved research evidence and translation for impactful national level policies. As 2019 marked the midway point, we assessed progress made on the five key priorities, and remaining work to be done, through global outreach to the growing network of academics, non-governmental organizations, advocates, social entrepreneurs, United Nations agencies, donors, and national governments. This paper delineates the key insights to inform and support the growing MHM commitment globally to maximize progress to reach our vision by 2024. Corresponding to the five priorities, we found that (priority 1) the evidence base for MHM in schools has strengthened considerably, (priority 2) global guidelines for MHM in schools have yet to be created, and (priority 3) numerous evidence-based advocacy platforms have emerged to support MHM efforts. We also identified (priority 4) a growing engagement, responsibility, and ownership of MHM in schools among governments globally, and that although MHM is beginning to be integrated into country-level education systems (priority 5), resources are lacking. Overall, progress is being made against identified priorities. We provide recommendations for advancing the MHM in Ten agenda. This includes continued building of the evidence, and expanding the number of countries with national level policies and the requisite funding and capacity to truly transform schools for all students and teachers who menstruate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

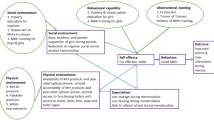

Over the last decade, evidence has accrued from around the world on the many barriers faced by schoolgirls to safe, hygienic, and dignified menstruation [1]. Challenges include limited or nonexistent information prior to menstrual onset [2]; inadequate health education about menstruation and puberty [3]; a lack of social support from teachers and peers for managing menses in school, and from families [4]; and insufficient access to water, sanitation, hygienic materials and disposal infrastructure. These barriers contribute to gender discriminatory physical school environments [5, 6] and pervasive menstruation-related stigma, enabling behavioral restrictions and feelings of shame, stress, and taboo [7]. Menstruation-related barriers are also associated with girls’ education [8,9,10]. This includes, for example, difficulty participating and engaging in the classroom, and thus achieving their potential, along with missed hours or days of school, and anxiety around menstrual accidents [11, 12]. Researchers have also identified associations with transactional sex in exchange for sanitary pads [13], increased vulnerability to pregnancy or child marriage, with subsequent school dropout or expulsion [14,15,16]; and bullying or teasing about menstruation by school boys [17]. These gendered educational realities may lead to negative reproductive and psychosocial outcomes, and diminished future economic opportunities. In turn, this may reinforce gender inequalities globally. Assuring the ability to manage menstruation safely and with dignity is essential to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for gender equality, good health, quality education, and sustainable water and sanitation for all; and related human rights. An essential aspect of addressing this issue are evidence-informed national level policies, and the resources to support their implementation.

As interest grew globally on the issue of menstruation in schools, an effort was undertaken to develop a ten-year agenda (2014–2024) with five corresponding priorities that address the intersection of girls’ education, health, gender and menstruation (Box 1). This endeavor incorporated inputs from global experts working on the issue of menstrual hygiene management (MHM), including academics, United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental (NGO) and advocacy organizations, private sector, social entrepreneurs, and national governments. The term MHM is used given it was the predominant term at the time referring to the components of managing menstruation with dignity and comfort, as defined by the Joint Monitoring Programme in 2012. The overarching aim was to collectively achieve, by 2024, a “MHM in Ten” vision [18]:

MHM in Ten Vision: Girls in 2024 around the world are knowledgeable and comfortable with their menstruation, and able to manage their menses in school in a comfortable, safe and dignified way.

The articulation of a “MHM in Ten” agenda and key priorities was a call to action to identify synergies and encourage and mobilize coordinated—rather than duplicative—efforts to address the MHM needs of schoolgirls through providing a roadmap for stakeholder engagement at global, national, and subnational levels, in the public and private sectors, and among development and humanitarian response actors [6].

Numerous organizations and institutions have incorporated the MHM in Ten vision and priorities into their menstruation-related planning and programmes, and the call to action has been cited over 108 times [18]. UNICEF continues to promote the importance of synergistic action in making progress on the agenda through requesting that during its annual virtual conference on MHM in schools indicate which priority (or priorities) the showcased work is advancing. Globally the evidence for action continues to grow, and a select number of national or sub-national level menstrual policies have been enacted. Five years have passed since the launching of the agenda, prompting a need to examine if and how progress is being achieved midway between the generation of the priorities and the ten-year endpoint. The aim of this paper is to present the findings from a narrative review conducted of research, programmes, policies, and initiatives focused on menstruation in schools across low- and middle-income countries to assess progress and gaps across the five priority areas identified, and to offer policy-oriented recommendations for global, regional, national, and subnational stakeholders. The insights from this review are intended for all actors working on MHM in schools to inform future effort, engagement, and investment required to achieve the collective MHM in Ten vision by 2024.

To review progress, we conducted a global desk review from April to June 2019. First, we identified 119 studies, programme reports, policies, systematic reviews, guidance documents and other documentation by searching a range of databases (Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, internal university database [CLIO] which catalogues over seven million articles, books, and archival content). Search terms included multiple combinations of the terms “advocacy”, “cost-effectiveness”, “data”, “effectiveness”, “evaluation”, “feasibility”, “gender”, “girls”, “global”, “government”, “guidance”, “guideline”, “impact”, “implementation”, “inclusive”, “indicator”, “international”, “menstrual health”, “menstrual hygiene management (MHM)”, “menstruation”, “national”, “policy”, “report”, “review”, “school(s)”, “systematic review”, “tool(kit)”, “trial”, “water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)”. These terms were also combined with the names of relevant organizations, networks, countries, regions, or international institutions to enhance relevance of results. Second, we contacted a total of 115 experts across sectors, including academics, NGOs, UN agencies, donors, governments, social entrepreneurs and advocates working in the MHM arena. Approximately 40% of the responses came from experts representing low-and middle-income countries, including government agencies, international agency country offices, and local NGOs. We began with all of the multi-sector participants of the initial and subsequent two annual follow-up MHM in Ten meetings held in 2014, 2015 and 2016 as well as those who presented at the UNICEF annual virtual conference on MHM in Schools. Electronic communications sent to all experts asked for: (1) updates and examples of progress being made to meet the five priorities; and (2) suggestions of additional organizations or experts to contact. Next, two members of the research team extracted information relevant to the five identified priorities from the documents identified from our search and the updates from experts. For the latter, we utilized an analysis approach developed in advance that incorporated key aspects of the priorities which we hoped to identify in relation to progress being made or not. These included, for example, examples of an expanding research base and general trends, the development of tools, the global state of the evidence, the inclusivity of research and programming, and other relevant categories that would indicate advancement or lack thereof. Finally, we selected examples across the priorities that illustrated progress being made or gaps where minimal progress has been achieved.

Update of progess since 2014

In the following sections we discuss each priority, detail known initiatives, and briefly note where further progress is urgently needed, particularly in the realm of evidence and policy. We acknowledge that all efforts globally are not captured, but have aimed to provide illustrative examples across sectors. The summaries below are intended to assess collective progress made by the global community working on the issue of menstruation across the articulated priorities. We do not intend to imply that that the MHM in Ten agenda is responsible for the initiatives noted. We have included in the Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 exemplars of progress and gaps across each priority, along with research, policy and related recommendations for advancing the agenda. In addition, we chose to include a select number of additional achievements across the MHM global community that while not specifically school-based, represent assessments or actions which contribute to national policy discussions and highlight population-level inequities, both of which are necessary to inform school menstrual health and hygiene policies and programmes.

Priority 1: Build a strong cross-sectoral evidence base for MHM in schools for prioritization of policies, resource allocation, and programming at scale.

The evidence base for MHM in schools has strengthened considerably since 2014. A key outcome of the first MHM in Ten meeting was the publication of research priorities for the 10-year agenda that summarized the evidence to date, articulated the gaps, recommended methodologies for future learning, and included a call for standardized measures within and across key sectors [19]. Progress has been made against the research needs that were identified. Overall, support from global funding bodies and research councils has increased, facilitating research beyond qualitative and descriptive studies [20] to include cross-sectional studies in Bangladesh [21], pilot intervention trials in Kenya, Uganda and the Gambia including varying combinations of WASH, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and education [23], intervention studies in Bangladesh and Uganda [24, 25]; full intervention trials in Kenya, and systematic reviews with meta-analyzes analyzing MHM-related evidence and measures and outcomes being utilized [1, 9, 10, 26,27,28,29]. In Kenya and the Philippines (see Boxes 2 and 3), evidence has fed directly into national policy and monitoring efforts influencing both countries’ education systems. These findings suggest that while important progress has been made to advance the evidence base, there is now a need for implementation science research to learn from these and other initiatives to understand how successful interventions, policies and programmes are delivered and scaled. In particular, the recommendations for advancing the agenda (see Table 1) articulate a range of empirical evidence needed, with topical and methodological areas described. This will be fundamental to informing advocacy efforts, along with and national and sub-national level policy.

Priority 2: Develop and disseminate global guidelines for MHM in schools with minimum standards, indicators, and illustrative strategies for adaptation, adoption, and implementation at national and subnational levels.

Although there does not exist broad consensus for one set of global guidelines, global and national level guidance for MHM in schools has been developed and disseminated (see Table 2). Country-specific examples include the Kenyan government’s design of guidelines on MHM strategy, policy, and a manual for training teachers, utilizing a multi-sector approach, and spearheaded by the Ministry of Health’s WASH group (see Box 2). Another country with existing guidelines is the Philippines government, which provides a useful example of a country that has integrated MHM indicators into their Education Monitoring Information System (EMIS). Early reports suggest that school-level MHM monitoring incentives improve compliance with standards, including the availability of emergency menstrual products in schools and the provision of adequate WASH facilities and MHM education (see Box 3).

Multiple efforts have fed into the development and provision of global level guidance. Since 2014, global guidance has emerged from multi-sectoral partnerships specific to the WASH and education sectors. Save the Children (2016) and UNICEF (2019) developed guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene, which encompasses the project cycle through design, delivery and evaluation UNICEF outlines a package of interventions that includes social support, knowledge and skills, facilities and services, and menstrual materials and supplies, all of relevance to schoolgirls. UNHCR has a mandate to provide sanitary products for displaced girls (and women), although not specific to the education sector. The MHM in Emergencies Toolkit, launched in 2017 with 27 co-publishing organizations, recommends the provision of sanitary products, female-friendly toilets, the provision of MHM and puberty information to girls, and the sensitization of teachers at schools with girls of menstruating age in emergency settings [30]. The WHO hosted a collaborative meeting in 2018 to identify strategic MHM contributions, and possible future guidelines, with a particular focus on the needs of girls, including the intersection with their education. While no global guidelines yet exist, given the varying contexts in which MHM-related programming and policy are implemented, having country-specific guidance may be of greater importance for transforming schools around MHM. However, having global guidance would serve as an important platform from which countries could tailor and adapt guidance at national and local levels.

Priority 3: Advance MHM in schools activities through a comprehensive evidence-based advocacy platform that generates policies, funding, and action across sectors and at all levels of government.

Numerous evidence-based advocacy platforms have emerged that have generated policies, funding and action (see Table 3). Global and national advocacy has served a critical role to advance the MHM in schools’ effort, including coverage by social and mainstream media, and individuals and organizations lobbying for action to address the range of menstruation-related needs of girls. Since 2014, an intensification of efforts focused on reducing menstruation-related stigma and raising awareness about schoolgirls’ MHM experiences and needs. MHM-compendiums like those developed from the 14 country UNICEF, UN Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) and Emory University-led WASH in Schools for Girls (WinS4Girls) effort have provided tools and evidence regarding MHM barriers in school, and subsequently, key messaging for advocacy initiatives (http://wins4girls.org/). Some partnerships have served to create spaces for young people to partake in the MHM conversation. For example, UNICEF and the School of Leadership in Pakistan invited girls and boys to design innovative MHM projects as part of the 16-country Generation Unlimited Youth Challenge. In Nepal and Pakistan, WaterAid used participatory photography so that girls could document experiences and challenges relating to MHM in schools; their exhibitions advocated to families, school authorities and local government for improvements. Although much of the global and local advocacy goes beyond girls in school, such efforts serve to reduce stigma around the topic, and potentially encourage governments and donor institutions to increase resources for MHM in schools specifically. Advocacy efforts are likely to increase pressure on governments and other stakeholders to develop and provide resources to implement relevant policies in education, health or other relevant areas, such as water and sanitation.

Priority 4: Allocate responsibility to designated government entities for the provision of MHM in schools including adequate budget and monitoring and evaluation [M&E]) and the reporting to global channels and constituents.

A growing number of government entities around the world have shown signs of engagement, responsibility, and ownership of MHM support in schools (see Table 4). Much of this can be attributed to the consistent advocacy efforts and systematic approaches incorporated, for example, by UNICEF’s WinS4Girls programme, which included a clear commitment from a government partner as criteria for selecting countries. In countries such as Kenya, important partnerships between government entities, researchers, and NGOs have played a key role in developing guidelines and uptake of MHM in schools (see Box 2). This provides an important example of research evidence translating into policy development processes at the country level. In many places, ownership and engagement by government actors provide an important mechanism for reducing menstruation-related stigma-related restrictions that girls may face, which in turn may impact girls’ ability to engage productively in school. In Afghanistan, the First Lady and two male ministers spoke openly about the topic of menstruation at a large event on MH Day in 2017; the First Lady of Kyrgyzstan made a statement at a WinS4Girls event; in Nepal, the President recently noted in a speech to Parliament that sanitary pads would be made available free of cost in all community schools; and in India, the subnational Government of Punjab committed to scale-up MHM initiatives in 54,000 schools. It will be important for governments to adopt monitoring and evaluation plans, and for those announcing national or provincial free or subsidized sanitary pad distribution programmes to create adequate disposal mechanisms in schools. As previously highlighted, the Kenya and Philippines policies provide useful examples of the way in which sustained government commitment and committed resources are needed to truly advance progress in schools (see Boxes 2 and 3).

This priority serves as a critical example of one in which commitment and resources are needed to truly advance progress, with important acknowledgement that there is not a “one size fits all” approach for each country per the responsible entities within a given government. Important to note is that many of the examples identified of government entities engaging on MHM were grounded in quality formative research conducted within each country around the MHM needs of girls in school, and to a lesser extent, intervention research; the latter is essential for assuring an effective and efficient use of limited resources.

Priority 5: Integrate MHM and the capacity and resources to deliver inclusive MHM into the education system.

MHM is beginning to be integrated into country-level education systems, however capacity and resources continue to lag, particularly around incorporating more inclusive approaches (see Table 5). In addition, limited national policies currently exist that explicitly incorporate attention to menstruation, which hinders the allocation of budget line items to build capacity and deliver effective programming. Yet a number of governments are taking promising steps towards increasing responsibility for providing MHM in schools. For example, in Zambia, the Ministry of General Education is rolling out the country’s MHM programme. In most countries, this has not yet translated to national action that is inclusive and accompanied with implementation and monitoring resources. While policies, standards and guidelines are growing, clear responsibility for implementation is not always clearly articulated, with financing often insufficient. The use, integration, operationalization, and scale-up of guidelines, for example, remains limited, even where there are plans to do so. In a number of countries, activities have been initiated. For instance, Nepal’s Integrating Menstrual Health and Hygiene in School Education, developed by the Family Welfare Division, is being piloted in different districts, supported by the German Corporation for International Cooperation GmbH (GIZ). Indonesia has used the National Health Programme (UKS) to test a roll out of an MHM package in schools, supported by the Ministries of Education and Health. Madagascar is planning a scale-up of MHM school activities in 2019, although smaller scale, and to date, Somalia has only implemented its institutional sanitation and hygiene promotion in a fraction of schools. The Gambia began to roll out a pilot initiative to implement minimum guidelines in 2018. In 2017, a study found that less than 20% of schools in rural Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia had four out of the five recommended menstrual hygiene services (e.g. sex-separate facilities, water supply, door with lock, waste disposal bin) [31]. And in high-income countries, legislative attention to addressing MHM in schools only very recently emerged. Much progress is needed across this priority to reach the vision of 2024, although the examples provided are useful for highlighting efforts underway, and potential models for other countries to follow. Truly impactful change on addressing the menstruation-related needs of girls and female teachers will only occur when policies—national or sub-national—are embedded within government institutions with the needed capacity and resources to deliver programming, and monitor impact and outcomes.

Expansion beyond schools

Although not within the scope of what could be included in this paper, there has been important progress made beyond schools in relation to menstruation, such as the inclusion of questions on menstruation and menarche in national levels surveys (MICS and DHS) as noted above, and the WHO’s 2018 Guidelines on Sanitation and Health which emphasize the importance of MHM-appropriate facilities, representing useful global guidance even if not specific to schools [32]. Additional efforts are underway to understand and address the needs of out of school girls, women, those in the workplace, and a more diverse range of menstrual experiences among populations in varying contexts. Part of this effort includes the evolution of definitions and terminology, such as Menstrual Health and Hygiene, defined well in UNICEF’s guidance [33], and a new definition for Menstrual Health is being developed by members of the Global Menstrual Collective There is also a critical need to assess and monitor how COVID-19 may widen disparities in relation to menstruation. The loss of family livelihoods may further exacerbate gendered access to and engagement in education. Menstrual health and hygiene should be considered as part of a safe return to school that considers all the gendered needs of girls.

Research and policy recommendations for advancing the agenda

To truly advance the MHM in Ten agenda in countries around the world, rigorous implementation research is needed to enable governments and donors to channel resources effectively, including contributing to the design of appropriate policies and related programs in a each country context. As differing government entities may be responsible and/or relevant for transforming girls’ experiences of menstruation in relation to school in each country, such as a sanitation and hygiene policy in one country, an education policy in many countries, and a health or gender related policy in other countries, it is essential that a foundation of relevant evidence be generated and translated as needed. To truly be impactful, enacted policies (or the relevant given entity in a sector, such as Education Sector Plans) should be linked with budget line items, and have operational plans and strategies that incorporate monitoring and evaluation to ensure implementation is happening as intended, and delivers the desired outcomes. As incorporated in this paper, a small number of countries are leading the way through their evidence-informed initial national level policy efforts [34].

Limitations

This MHM in Ten progress update was conducted through a desk review and outreach to the ever-growing network of experts and organizations working on menstrual health and hygiene, with an expanded number of individuals and organizations contacted. This brief review does not represent all activities worldwide and much of the MHM progress may not be identified easily through existing documentation, as government documents may not be shared widely and/or be available only in local languages. Therefore, this review likely under-represents progress. Nevertheless, we hope that this review will inspire reporting and the expansion of the MHM in Ten network to enable a stronger review by 2024, with gains achieved across the five priorities, either through direct action or indirect efforts that contribute to meeting the vision.

Conclusions

MHM is now recognized globally as a definitive public health and development issue, with substantial increase in financial and human capital committed toward this topic. While progress has been made across the five priorities in a range of countries, and is moving towards the vision for 2024 directly or indirectly, much remains to be done. Gaps in progress cannot be filled until resources and political commitments are made to transform schools for menstruating girls. The SDGs present an opportunity for greater prioritization of the issue of MHM for schoolgirls, including increased integration across sectors and improved monitoring of progress. They also provide pressure on governments to enact relevant policies that enable transforming education systems at scale. Progress was primarily identified in countries across Priorities 1, 2 and 3, with Priorities 4 and 5, requiring government engagement and capacity, highlighted as areas for attention in the second half of the ten-year agenda.

Key recommendations for actions that will advance the agenda include support for learning from implementation of government programmes and policies to share across country governments, longitudinal research to measure relevant impact and outcomes; improved investment in the evidence base for addressing MHM in schools, particularly research targeting the most underserved; a better understanding of costs and effectiveness, and the benefits of comprehensive, cross-sectoral approaches. Together these actions will contribute to meeting the vision that all girls in 2024 are knowledgeable and comfortable with their menstruation, and able to manage their menses in school in a comfortable, safe and dignified way.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Hennegan J, Shannon AK, Rubli J, Schwab KJ, Melendez-Torres GJ. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(5).

Deo G. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: a comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med [Internet]. 2005;30(1):33–33. http://medind.nic.in/iaj/t05/i1/iajt05i1p33.pdf. Accessed 2 Aug 2019.

Crockett LJ, Deardorff J, Johnson M, Irwin C, Petersen AC. Puberty education in a global context: Knowledge gaps, opportunities, and implications for policy. J Res Adolesc [Internet]. 2019;29(1):177–95. http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12452. Accessed 2 Aug 2019.

Haver J, Long JL, Caruso BA, Dreibelbis R. New directions for assessing menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in schools: a bottom-up approach to measuring program success. Stud Soc Justice. 2018;12(2):372–81.

Alexander KT, Oruko K, Nyothach E, Mason L, Odhiambo FO, Vulule J, et al. Schoolgirls’ experiences of changing and disposal of menstrual hygiene items and inferences for WASH in schools. 2015 http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3362/1756-3488.2015.037. ISSN:0262-8104.

Sommer M, Kjellén M, Pensulo C. Girls’ and women’s unmet needs for menstrual hygiene management (MHM): the interactions between MHM and sanitation systems in low-income countries. J Water, Sanit Hyg Dev [Internet]. 2013;3(3):283–97. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/docview/1943052555/fulltextPDF/70077594951D462DPQ/1?accountid=10226. Accessed 2 Aug 2019.

Sommer M, Ackatia-Armah N, Connolly S, Smiles D. A comparison of the menstruation and education experiences of girls in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Comp A J Comp Int Educ [Internet]. 2015;45(4):589–609. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.871399. Accessed 2 Aug 2019.

Schoep ME, Adang EMM, Maas JWM, De Bie B, Aarts JWM, Nieboer TE. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32 748 women. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2019;9(6):e026186.

Sumpter C, Torondel B. A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. RezaBaradaran H, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013;8(4):e62004. http://dx.plos.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062004. Accessed 21 Sep 2019.

Hennegan J, Montgomery P. Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. Thompson Coon J, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016;11(2):e0146985. https://dx.plos.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146985. Accessed 21 Sept 2019.

Alam M-U, Luby SP, Halder AK, Islam K, Opel A, Shoab AK, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among Bangladeshi adolescent schoolgirls and risk factors affecting school absence: results from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2017;7(7):e015508. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Chinyama J, Chipungu J, Rudd C, Mwale M, Verstraete L, Sikamo C, et al. Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: a descriptive study of knowledge, experiences and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019;19(1):16. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6360-2. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Phillips-Howard PA, Otieno G, Burmen B, Otieno F, Odongo F, Odour C, et al. Menstrual needs and associations with sexual and reproductive risks in rural Kenyan females: A cross-sectional behavioral survey linked with HIV prevalence. J Women’s Heal [Internet]. 2015;24(10):801–11. http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.5031. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Prakash R, Beattie T, Javalkar P, Bhattacharjee P, Ramanaik S, Thalinja R, et al. Correlates of school dropout and absenteeism among adolescent girls from marginalized community in north Karnataka south India. J Adolesc. 2017;61:64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.007.

Sekine K, Hodgkin ME. Effect of child marriage on girls’ school dropout in Nepal: analysis of data from the multiple indicator cluster survey 2014. Gammage S, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017;12(7):e0180176. https://dx.plos.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180176. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Wodon Q, Nguyen MC, Tsimpo C. Child marriage, education, and agency in Uganda. Fem Econ [Internet]. 2016;22(1):54–79. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1102020. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Mason L, Nyothach E, Alexander K, Odhiambo FO, Eleveld A, Vulule J, et al. “We keep it secret so no one should know” - A qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural Western Kenya. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013;8(11):e79132. www.plosone.org. Accessed 5 Aug 2019.

Sommer M, Caruso BA, Sahin M, Calderon T, Cavill S, Mahon T, et al. A time for global action: addressing girls’ menstrual hygiene management needs in schools. PLOS Med [Internet]. 2016;13(2):e1001962. http://dx.plos.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001962. Accessed 2 Aug 2019.

Phillips-Howard PA, Caruso B, Torondel B, Zulaika G, Sahin M, Sommer M. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low- and middle-income countries: research priorities. Glob Health Action [Internet]. 2016;9:33032.

Sommer M. Putting menstrual hygiene management on to the school water and sanitation agenda. Waterlines [Internet]. 2010;29(4):268–78. www.practicalactionpublishing.org. Accessed 9 Aug 2019.

ICDDRB. Bangladesh National Hygiene Baseline Survey Preliminary Report. WaterAid Bangladesh, Local Government Division. Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2014.

National Institutes of Health. Cups or cash for girls trial to reduce sexual and reproductive harm and school dropout [Internet]. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03051789. Accessed 9 Aug 2019.

Miiro G, Rutakumwa R, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Nakuya K, Musoke S, Namakula J, et al. Menstrual health and school absenteeism among adolescent girls in Uganda (MENISCUS): a feasibility study. BMC Womens Health [Internet]. 2018;18(1). https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0502-z. Accessed 9 Aug 2019.

Emdadul Haque S, Rahman M, Itsuko K, Mutahara M, Sakisaka K. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: an intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2014;4:4607. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/. Accessed 9 Aug 2019.

Burgers L, Yamakoshi B, Serrano M. Wash in schools empowers girls’ education: proceedings of the 7th annual virtual conference on menstrual hygiene management in schools [Internet]. New York; 2019. www.unicef.org/wash. Accessed 11 Aug 2019.

van Eijk AM, Sivakami M, Thakkar MB, Bauman A, Laserson KF, Coates S, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2016;6(3):e010290.

Wilbur J, Torondel B, Hameed S, Mahon T, Kuper H. Systematic review of menstrual hygiene management requirements, its barriers and strategies for disabled people. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019;14(2):e0210974.

Birdthistle I, Dickson K, Freeman M, Javidi L. What impact does the provision of separate toilets for girls at schools have on their primary and secondary school enrolment, attendance and completion?: A systematic review of the evidence [Internet]. London; 2011. https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/Birdthistle-2011-What.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept 2019.

Shannon AK, Melendez-Torres GJ, Hennegan J. How do women and girls experience menstrual health interventions in low-and middle-income countries? Insights from a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. Cult Health Sex [Internet]. 2020; https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tchs20. Accessed 8 May 2019.

Sommer M, Schmitt M, Clatworthy D. A toolkit for integrating menstrual hygiene management (MHM) into humanitarian response [Internet]. New York; 2017. https://www.wsscc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/The-MHM-Toolkit-Full-Guide.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2019.

Morgan C, Bowling M, Bartram J, Lyn Kayser G. Water, sanitation, and hygiene in schools: status and implications of low coverage in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia. Int J Hyg Environ Health [Internet]. 2017;220(6):950–9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1438463916305594?via%3Dihub. Accessed 11 Aug 2019.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on sanitation and health [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018. http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/guidelines-on-sanitation-and-health/en/. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

UNICEF. Gender Action Plan 2018–2021 | UNICEF [Internet]. https://www.unicef.org/gender-equality/gender-action-plan-2018-2021. Accessed 8 May 2019.

Sommer M, Figueroa C, Kwauk C, Jones M, Fyles N. Attention to menstrual hygiene management in schools: An analysis of education policy documents in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Educ Dev [Internet]. 2017;57:73–82. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738059317302316. Accessed 10 Aug 2019.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the experts working globally who so generously responded to our request for inputs and provided updates from progress being made or perceived gaps from around the world.

Funding

The Water Sanitation and Supply Collaborative Council (WSSCC) generously provided support for the conduct of this review and manuscript preparation. Additional support for MS was provided by the Sid and Helaine Lerner MHM Faculty Support Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and ECW conceptualized the manuscript and wrote the initial draft; BAC, BT, BY, JH, JL, TM, EN, NO, and PP-H provided extensive inputs and edits. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required for the conduct of this review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sommer, M., Caruso, B.A., Torondel, B. et al. Menstrual hygiene management in schools: midway progress update on the “MHM in Ten” 2014–2024 global agenda. Health Res Policy Sys 19, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00669-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00669-8