Abstract

Background

Knowledge translation (KT) is currently endorsed by global health policy actors as a means to improve outcomes by institutionalising evidence-informed policy-making. Organisational knowledge brokers, comprised of researchers, policy-makers and other stakeholders, are increasingly being used to undertake and promote KT at all levels of health policy-making, though few resources exist to guide the evaluation of these efforts. Using a scoping review methodology, we identified, synthesised and assessed indicators that have been used to evaluate KT infrastructure and capacity-building activities in a health policy context in order to inform the evaluation of organisational knowledge brokers.

Methods

A scoping review methodology was used. This included the search of Medline, Global Health and the WHO Library databases for studies regarding the evaluation of KT infrastructure and capacity-building activities between health research and policy, published in English from 2005 to 2016. Data on study characteristics, outputs and outcomes measured, related indicators, mode of verification, duration and/or frequency of collection, indicator methods, KT model, and targeted capacity level were extracted and charted for analysis.

Results

A total of 1073 unique articles were obtained and 176 articles were qualified to be screened in full-text; 32 articles were included in the analysis. Of a total 213 indicators extracted, we identified 174 (174/213; 81.7%) indicators to evaluate the KT infrastructure and capacity-building that have been developed using methods beyond expert opinion. Four validated instruments were identified. The 174 indicators are presented in 8 domains based on an adaptation of the domains of the Lavis et al. framework of linking research to action – general climate, production of research, push efforts, pull efforts, exchange efforts, integrated efforts, evaluation and capacity-building.

Conclusion

This review presents a total of 174 method-based indicators to evaluate KT infrastructure and capacity-building. The presented indicators can be used or adapted globally by organisational knowledge brokers and other stakeholders in their monitoring and evaluation work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Health research is largely an untapped resource in policy-making; while there is an abundance of health research conducted worldwide, the translation of research into policy can be slow or even non-existent [1, 2]. Knowledge translation (KT) — a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge [3] — has been advocated in high level policy meetings and echoed in practice by major health policy actors like WHO as a key approach for linking research and policy [4,5,6,7]. KT has been implemented in a variety of disciplines using several different, often overlapping frameworks [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The Lavis et al. [14] framework developed to assess country-level efforts to link research to action has been widely adopted in the health policy arena [14,15,16,17]. The framework provides four key domains to guide country-level KT efforts, namely (1) the climate for research use; (2) the production of research that is both highly relevant to and appropriately synthesised for research users; (3) the mix of clusters of activities used to link research to action; and (4) the evaluation of efforts to link research to action [14]. Within their framework, Lavis et al. classify KT activities into four models of push, pull, exchange and integrated efforts [14].

Push efforts are often researcher-led and include efforts to disseminate user-friendly knowledge or seek policy-relevant research questions [14]. User pull efforts include activities to support policy-makers in searching and using evidence for decision-making [14, 17, 18]. Exchange efforts involve fostering joint interaction, collaboration and partnerships between research producers and users [14, 17]. Integrated efforts incorporate pull, push and exchange efforts and are often facilitated through knowledge brokers (individuals or organisations/networks) that bring together policy-makers, researchers and other stakeholders to conduct KT activities [14, 17]. These activities outlined in the framework largely contribute to KT by building capacity (i.e. skills development and continuing education) and the development of KT infrastructure [14]. For the purposes of this study, we adopted the Ellen et al. [19] definition of research knowledge infrastructure to define KT infrastructure as any instrument (i.e. programmes, interventions, tools, devices) used to facilitate the access, dissemination, exchange and/or use of evidence.

Integrated efforts using organisational knowledge brokers to facilitate KT are widely used by global policy actors to develop capacity and infrastructure at the country-level [6, 17, 20,21,22]. Organisational knowledge brokers involve the development of multisectoral bodies comprised of researchers, policy-makers and other stakeholders to collaboratively facilitate KT [17, 23]. One such initiative is the multi-year programme, Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) developed by the Evidence for Policy Design from the Harvard Kennedy School in collaboration with United Kingdom Aid [24]. The BCURE programme developed organisational knowledge brokering projects across 12 low- and middle-income countries from 2013 to 2017 and built KT capacity in over 560 stakeholders [20]. A similar initiative from the McMaster Health Forum in Canada, the Partners for Evidence-driven Rapid Learning in Social Systems (PERLSS), is currently working to establish organisational knowledge brokers and strengthen KT capacity in 13 partner countries, with the aim of supporting countries in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals [21, 25].

Recognising that many countries face low KT capacity, coupled with requests from Member States to develop innovative mechanisms for bridging the research-to-policy gap, the WHO launched its organisational knowledge brokering initiative in 2005 called the Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) [6, 26, 27]. Operating at the global, regional and national levels, EVIPNet’s aim is to support national policy-makers, researchers and other stakeholders to systematically and transparently use high-quality evidence in policy-making [6]. EVIPNet establishes country-level organisational knowledge brokers, so-called KT Platforms (KTPs) under the EVIPNet terminology, as a means to build capacity and institutionalise KT infrastructure in network participant countries [17, 23]. EVIPNet’s KTPs develop products such as rapid response services, evidence briefs for policy and policy dialogues, and conduct capacity-building exercises with national stakeholders to retrieve, assess, synthesise, package and use evidence [6].

The European arm of EVIPNet (EVIPNet Europe), for example, launched under the umbrella of the WHO European Health Information Initiative, has supported 21 network participant countries in KT capacity-building and infrastructure development since its inception in 2012 [28]. Network members have developed a range of KT instruments in recent years that catalyse policy change at the national level and several countries have successfully implemented preliminary steps to institutionalise KTPs [28, 29]. By improving health policy-making processes, EVIPNet Europe supports the implementation of regional and global policy goals such as the Health 2020 European policy framework [30], the Action Plan to Strengthen the Use of Evidence, Information and Research for Policy-making in the WHO European Region [31] and the Sustainable Development Goals [25].

While there has been some evaluation of these efforts, mainly from programme leadership [28, 32, 33], challenges related to the low capacity of organisational knowledge brokers to evaluate their own activities have been noted [16]. Low capacity coupled with the complexity of policy-making processes, which are often influenced by a number of factors that make attributing policy and health outcomes to any one aspect difficult, can create challenges for organisational knowledge brokers to evaluate their work [34, 35]. Using high-quality, evidence-informed indicators can support organisational knowledge brokers and ensure greater attribution to their efforts [36]. While impact evaluation is important and work has been done in this area [37, 38], focusing on shorter and intermediate evaluation indicators is more likely to result in greater attribution to KT activities [39]. For this reason, our study focuses solely on output indicators (measure programme outputs including products, goods and services resulting from an intervention) and outcome indicators (measure the short- and medium-term effects of an intervention’s outputs) [40].

While there has previously been a lack of indicators to evaluate KT activities [41, 42], some work has been done in this area in recent years [38, 43]. For example, Tudisca et al. [38] have developed 11 indicators to assess evidence use in policy-making using a Delphi study; however, the study does not include indicators to assess KT activities. Maag et al. [43] have collected and assessed indicators for measuring the contributions of knowledge brokers but the study is not specific to health policy and focuses on individual knowledge brokers; consequently, it lacks indicators to assess the development of KT infrastructure at the country level, which is a main aim of the organisational knowledge brokers currently active in the global health policy arena. The aim of this study was to identify, synthesise and assess indicators that have been used to evaluate KT infrastructure and capacity-building activities, in order to support organisational knowledge brokers and their stakeholders in evaluation.

Methods

We have used the scoping review methodology as outlined in the Arksey and O’Malley [44] framework. This included (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying the relevant studies; (3) determining the study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results [44]. The following research questions guided the review: What indicators have been used to measure KT infrastructure and capacity-building in evaluation literature? What percentage of indicators are based on previously developed methods or are validated?

A search strategy was developed, piloted and refined in consultation with a team of medical librarians at Karolinska Institutet (see Additional file 1 for full search strategy). Three databases were used, namely Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Global Health and the WHO Library Database – a combination that searched both peer-reviewed and grey literature. Additional literature was collected via reference searching of eligible articles and manual addition by the authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To capture the indicators relevant for organisational knowledge brokers, we included studies evaluating KT infrastructure or KT capacity-building. The inclusion criteria consisted of (1) studies published in English language, from January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2016 (the year 2005 was used as the lower cut-off year for the search since investments into increasing the linkages between research and policy substantially increased globally with World Health Assembly 58 resolution [5]); (2) studies that evaluated KT infrastructure or capacity-building efforts between research and policy-making, only. Due to the heterogeneity of the topic, the review was limited to the research–policy gap, though other forms of KT between researchers, communities, patients and clinicians could contribute useful indicators and/or perspectives; and (3) studies conducted on the macro scale, which was defined as an administrative geographical level of policy-making or research activity occurring at the national or supranational level.

All types of study designs were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded from analysis if they (1) did not evaluate or develop an evaluation framework for a KT infrastructure or capacity-building intervention or mechanism for increasing KT or evidence-informed policy-making (EIP); (2) discussed KT infrastructure or capacity-building in individual clinical decision-making or described capacity to implement evidence-based interventions or capacity-building efforts to front-line staff; (3) described or evaluated KT tools and products without focusing on infrastructure or capacity-building; (4) described capacity-building efforts with no intervention regarding KT or researcher–policy interaction; (5) described indicators to measure capacity, without a capacity-building effort implemented or described; (6) described a KT capacity-building effort between researchers and policy-makers at the sub-national level (however, some cases that fell into this distinction were included as they were deemed to be equally autonomous to the national level given the unique situation of the country); (7) focused on community-based participatory research, incorporating community needs in interventions or policy; (8) described the dissemination of evidence-based interventions or of quality improvement interventions; (9) focused on coalition and network best practices for achieving a goal besides KT; (10) were studies that fell under the category of implementation science (while similar and even complementary to KT, implementation science focuses more on barriers and facilitators of delivering an intervention, rather than the processes of evidence use [45]); or (10) had no published abstract.

All authors were involved in developing the search criteria and data extraction tool. Article screening, data extraction and charting were led by one reviewer (JS) and verified with a second reviewer (ZEK) when eligibility was unclear. The final references included for analysis and the extracted data were presented to and reviewed by all authors. While having two independent reviewers is ideal, the literature notes that the scoping review methodology can be adapted for feasibility, for example, by using one reviewer and a second reviewer to verify the data [46]. This modified approach was most feasible for our study given the available resources.

Screening of the collected data was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart [47], where first duplicate records were removed and then screened by title and abstract. For those abstracts for which eligibility was uncertain, full text articles were reviewed. Included articles were then reviewed in their full text. The following data items were extracted from the included literature and charted for analysis: title, author, year, country, study design, evaluation method, outputs and indicators, outcomes and indicators, mode of verification, duration and/or frequency of collection, and indicator methods. The domains of the Lavis et al. [14] research-to-action framework were used to categorise the output and outcome indicators. The conditions for each domain, that if met would likely be conducive for effective KT, were also used to guide our suggestions for applying the indicators (Table 1) [14].

Indicator methods were assessed by the extent to which they were informed by evidence, where expert opinion was considered least rigorous and validation procedures as most rigorous. Indicators that were informed by previously published frameworks, tools or literature, or developed using qualitative methods, were deemed to have been informed and included. When indicator sources were not mentioned or authors failed to provide a comprehensive description of indicator methods, the indicators were not deemed to be informed and were excluded.

No ethical approval was necessary to conduct this study, as it collected publicly published reports.

Results

Study characteristics

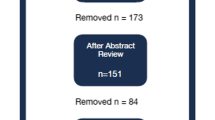

Of 1231 articles obtained from the database search, reference searching and manual addition, 32 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this study. The full study selection process with reasons for exclusion is outlined in Fig. 1.

Of the 32 eligible studies, 3 articles were study protocols for a randomised control trial (RCT), 3 studies were general evaluation frameworks and 1 study developed indicators for use in monitoring and evaluation (M&E). The remaining 25 studies were programme/intervention evaluations. Participants and target audiences were mainly policy-makers (n = 21/32) and researchers (n = 17/32). Other targeted populations included the public sector, academic and research institutions, healthcare personnel and institutions, non-governmental organisations and advocacy groups, development agencies, media, donors and funders, and civil society. More details of study characteristics can be seen in Additional file 2.

Of the 32 studies, integrated efforts and push efforts were the most represented with 9 studies each. Specific integrated efforts included KT brokering (n = 4), secretariat technical assistance (n = 1), KTPs/organisational knowledge brokers (n = 3) and research networks (n = 1). Push efforts included research funding (n = 4), research platforms (n = 2), researcher capacity-building academic programmes (n = 1), complex interventions (n = 1) and research partnerships (n = 1). Seven studies (n = 7/32) represented linkage and exchange efforts, which included research partnerships and platforms (n = 3), KT and knowledge exchange networks (n = 2), buddying (n = 1), and complex systems interventions (n = 1). User pull activities included workshops (n = 2), a workshop with mentoring (n = 1), a conference (n = 1), an organisational complex intervention (n = 1), online resources (n = 1) and technical assistance (n = 1). Capacity-building efforts were found to be mainly focused on producer push and user pull, whereas infrastructure was mainly focused on exchange and integrated efforts. The main KT infrastructural tools included platforms, partnerships, networks, and KTPs or other organisational knowledge brokers.

Indicators organised by domain

All 32 studies reported outputs, with fewer reporting outcomes (n = 26/32). Output and outcome indicators were organised using the domains included in the Lavis et al. [14] framework for assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. One domain from the original framework, ‘efforts to facilitate user pull’, was revised to ‘integrated efforts’ for the purposes of this study. This revised domain includes facilitation not only of pull efforts but also of push and exchange efforts, since organisational knowledge brokers facilitate KT across all three activities [17]. ‘Capacity-building’ was also added as an additional domain. Capacity-building is included in the Lavis et al. [14] framework but is not a separate domain. We chose to highlight these indicators in a dedicated section since they apply to many of the other domains. Table 1 includes a full description of the eight domains used to categorise the collected indicators and the conditions outlined in the framework that, if met, would likely be conducive for KT.

In total, 213 indicators were identified, including 181 output indicators and 32 outcome indicators. Of the 213 indicators identified, 174 (81.7%) were based on methods beyond expert opinion (i.e. literature review, frameworks, published tools) or had been validated. Of these, 155 were output indicators and 19 were outcome indicators. Indicators that were based on literature review, pre-existing frameworks or were validated are presented in Table 2. Most studies developed indicators specifically for the evaluation highlighted in the study and used non-systematic literature review, theoretical frameworks, published tools and/or expert opinion. One study developed indicators using literature review and focus groups with stakeholders, one study developed and validated indicators, and three studies used previously validated indicators.

Four of the 32 studies used the validated indicators (as noted by an a in Table 2). Three of the four studies were part of the same project, which used indicators from the validated Is Research Working for You? tool [48,49,50]. Other validated tools included the Staff Assessment of engagement with Evidence (SAGE), Seeking, Engaging with, and Evaluating Research (SEER), and Organisational Research Access, Culture and Leadership (ORACLe) [41]. These indicators were mainly used to evaluate capacity, not KT infrastructure. They are derived from both qualitative and quantitative methods, using interviews or questionnaires as evaluation methods. As a capacity measure, these indicators were used in pre/post interventions as both a baseline and outcome measures [41, 48,49,50].

Measure descriptions of the four validated indicators and tools: | |

• ORACLe Measures: capacity (policies that encourage or mandate the examination of research in policy and programme development; tools, systems, training and programmes to assist with accessing, appraising and generating research). | |

• SEER Measures: capacity (value placed on research, perceived value organisation places on research; confidence in skills and knowledge to access, appraise and generate research; perceived availability of organisational tools, systems, training and programmes to assist with accessing, appraising and generating research); research engagement actions (self-reported extent of accessing, appraising and generating research, and interaction with researchers); research use (self-reported use of research). | |

• SAGE Measures: research engagement actions (accessing research, appraising research (for quality and relevance), generating new research or analysis, and interacting with researchers) and research use (four types of research use are considered: instrumental, tactical, conceptual and imposed) in each policy document and the context in which the policy document was produced, including barriers and facilitators. | |

• Is Research Working for You? Tool This tool was developed in 2009 by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (formerly the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation) and includes 88 items to measure culture for EIP and use of evidence at the individual and/or organisational level. |

Discussion

We identified 213 unique output and outcome indicators related to KT infrastructure and capacity-building, of which 174 were based on methods beyond expert opinion. Few of the indicators had been validated or assessed for rigor and many studies did not report methods for selecting indicators at all. The literature notes the common trade-off that exists between collecting data with quality indicators versus collecting data that is already being used for monitoring [40], which may be a driving factor that many indicators were not explicitly described or based on methods. The indicators measured using the four validated tools (SEER, SAGE, ORACLe and Is Research Working for You? [41, 48,49,50]) should be highlighted as the most rigorous indicators collected in this review.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to identify indicators to evaluate KT infrastructure and capacity-building activities specific to organisational knowledge brokers in a health policy-making context. Maag et al. [43] and Tudisca et al. [38] have both published indicator lists, the former to assess the contributions of individual knowledge brokers and the latter to assess the use of evidence in policy-making. Our study is distinguished from these other indicator studies as we collected indicators to assess organisational knowledge brokers in their work to build capacity and KT infrastructure. It is also distinguished from the Gagliardi et al. [51] scoping review that synthesised 13 evaluation studies of integrated KT activities across varied healthcare settings since our study extracted and assessed evaluation indicators. The indicators synthesised in this study are both generalisable and transferable to other KT infrastructural and capacity-building efforts at the national and regional levels, given the broad eligibility criteria. However, since the indicators presented in this synthesis are broad indicators that should be adapted to the specific needs and activities of KT stakeholders [52], the transferability and generalisability of the indicators may not affect their practical use.

Applying the indicators in practice

The summary list of indicators can guide the evaluation of organisational knowledge brokers, such as the KTPs implemented under EVIPNet as well as similar capacity-building initiatives that operate via organisational knowledge brokers [20,21,22]. For example, this list has been presented to the WHO Secretariat of EVIPNet Europe and has already been used in EVIPNet Europe’s mid-term evaluation and M&E framework. We have also provided data on mode of verification, method and frequency of collection for each indicator in Additional file 3 to guide stakeholders in applying them in practice.

In selecting indicators to assess country-level KT indicators, we suggest stakeholders use the Lavis et al. [14] framework as a guide. In particular, the conditions outlined under each domain that, if met, would likely be conducive with linking research to action; these conditions are outlined in Table 1 above. Additionally, there are several factors that should be carefully considered when selecting indicators for M&E. Current evaluation literature recommends using a mix of both qualitative and quantitative indicators [52]. Qualities such as validity, acceptability, feasibility, sensitivity and predictive validity should also be considered [40]. The related costs and resources required for the collection of an indicator are also determining factors in selecting M&E indicators and, often, such factors may result in the use of indicators based on existing data or data collection instruments over the ‘best fit’ indicator [40]. Selecting fewer but essential and higher quality indicators can mitigate such trade-off [40]. Based on these considerations, we outline a few examples of using the presented set of indicators to evaluate organisational knowledge brokers. The two examples highlight that, for some activities, there may be one composite indicator available (when multiple indicators are compiled into a single index [53]) and, for other activities, stakeholders may need to select a variety of indicators based on the type of activity they are evaluating.

To assess the general KT climate, for example, a programme may be interested in evaluating current outputs or outcomes of KT activities. Since there is a validated output indicator to assess the general climate, we suggest that stakeholders use the indicator ‘the organisation has the skills, structures, processes and a culture to promote and use research findings in decision-making’, which is collected using the Is Research Working for You? tool [48,49,50]. This indicator will assess most of the considerations detailed in the Lavis et al. [14] framework that include structural supports and individual value of research use. The indicator can be used to assess both organisations and individuals, and can be used both as a pre-test assessment to understand the current state of the KT climate or as a post-test assessment to understand if KT activities have contributed to an improved climate [48,49,50]. Similarly, this study collected three composite indicators – SEER, ORACLe and SAGE – that can be used to evaluate both the outputs and outcomes of pull efforts. These indicators can also be used as pre/post-test assessments [41].

On the other hand, to assess push efforts, stakeholders may need to use a variety of indicators since there is no one indicator that captures all conditions outlined by Lavis et al. [14]. The condition of developing user-friendly messages from the evidence can be evaluated using a validated indicator, ‘research is presented to decision-makers in a useful way’, which is also measured using the Is Research Working for You? tool [48,49,50]. However, stakeholders may also be interested in assessing their outputs of strategies employed to encourage the use of evidence. To do so, we recommend using a few output indicators that apply to the strategy taken. For example, if an organisational knowledge broker disseminated research findings and actionable messages using a website, it may be useful to collect data on the number of downloads, number of page visits and number of countries visiting the website since these three indicators will provide a snapshot of reach and level of engagement. Outcomes of these strategies are also likely of importance to stakeholders. The four outcome indicators collected to assess push efforts all capture distinct items: use of research, behaviour change, increased interest in KT from researchers and changes in funding. The first two indicators, ‘number of project findings used/expected to be used in policy’ and ‘number of projects leading to/expecting to change behaviour’ would demonstrate the effect of efforts on evidence use, while the latter two indicators, ‘increase in inquiries and applications’ and ‘phasing out of external funding’ would rather demonstrate the effect of efforts on sustainability. Selecting which indicator would be best and how many to use would ultimately depend on the type of work being assessed, the goals of the evaluation, data availability and resources.

Limitations and further research

The findings are limited in scope since only articles published in English were included. Ensuring a comprehensive list of search terms was important to minimise bias in study representation towards a particular country, region, organisation or funder given that the KT terminology used varies widely by such factors [54]. Careful attention was paid to develop a comprehensive search strategy, which was informed by a literature search and piloted several times in consultation with medical librarians. The use of only two databases, both of which are health focused, may have excluded relevant studies from other disciplines. However, the peer-reviewed database search was supplemented using grey-literature databases, reference searching and manual addition.

Despite developing inclusion and exclusion criteria, decisions on eligibility often needed to be interpreted due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the topic. While only one reviewer screened and analysed the data, a second reviewer was consulted where eligibility was unclear. We acknowledge this as a limitation of our work, since having two reviewers is ideal under the Arksey and O’Malley framework [44]. However, our modified approach using one reviewer and a second reviewer to verify results has been used by other stakeholders in the field and was carefully developed to be robust while still being feasible for our study given the available resources [46]. The challenges faced due to the complexity of the KT field further emphasise the previous calls for action on developing a more uniform KT vocabulary and adding to existing efforts [55]. Due to a widespread lack of detail regarding evaluation and indicator methods, some rigorous or method-based indicators may have been excluded. Many studies did not explicitly state which indicators were used as output or outcome indicators and were then categorised by judgement of the reviewer.

Further analyses using the Delphi method and stakeholder interviews can contribute to our findings regarding the comprehensiveness, acceptability and feasibility of the presented indicators [40]. A complementing review to identify institutionalisation indicators to assess the extent to which organisational knowledge brokers have been systematically integrated into national health policy-making would be useful. By organising the collected indicators with the Lavis et al. [14] framework domains we have also identified opportunities for further work with indicator development and validation. For example, there was a minimal number of indicators identified to assess programme’s evaluation efforts. This may be due to a potential lack of evaluation occurring in the field. Additionally, this review found no validated indicators that have been used to evaluate exchange efforts. The literature on the institutionalisation of organisational knowledge brokers is also scarce and further work, including developing institutionalisation frameworks, would aid the development of institutionalisation indicators.

M&E provides valuable insight for quality improvement and can help strengthen organisational knowledge brokers in their work to make the policy-making process more systematic and transparent. This is particularly important since policy-making is a complex process, often influenced by political will and obligation, civil society needs and opinion, cultural norms, resource considerations, lobbying and advocacy [34, 35]. Strong KT infrastructure provided by organisational knowledge brokers can support more equitable and efficient policies [56]. Demonstrating the effectiveness of organisational knowledge brokers through M&E is particularly important for sustainability, as it can lead to greater funder interest and buy-in. Strong support for organisational knowledge brokers will help countries work towards the EIP goals they have agreed to [4, 5, 7] and assist them in meeting current policy targets [30].

Conclusion

The gap between research and policy is a result of several competing factors, one of which is a lack of capacity for EIP [27]. More specifically, many countries do not have the structural capacity to systematically and transparently use high-quality evidence. Efforts to support countries in developing such systems using organisational knowledge brokers have been implemented in cooperation with several global and local stakeholders. WHO’s EVIPNet, as an example, works collaboratively with countries to develop organisational knowledge brokering platforms comprised of researchers, policy-makers and other stakeholders [6].

M&E is vital for ensuring the success and sustainability of organisational knowledge brokers. However, resources for evaluating organisational knowledge brokers in a health policy context are limited. As organisational knowledge brokers are implemented and become more established, it is important to build stakeholder capacity to evaluate their work. This review presents a total of 174 method-based indicators to evaluate KT infrastructure and capacity-building. Four validated instruments, namely SEER, SAGE, ORACLe and Is Research Working for You? [41, 48,49,50], were also identified. While this study provides a critical starting point for future development of KT indicators, the presented indicators in their current form can be used or adapted globally by organisational knowledge brokers and other stakeholders in their M&E work.

Abbreviations

- EIP:

-

Evidence-informed policy-making

- EVIPNet:

-

Evidence-informed Policy Network

- KT:

-

Knowledge translation

- KTP:

-

Knowledge translation platform

- M&E:

-

Monitoring and evaluation

- ORACLe:

-

Organisational Research Access, Culture and Leadership

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- SAGE:

-

Staff Assessment of enGagement with Evidence

- SEER:

-

Seeking, Engaging with and Evaluating Research

References

Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104:510–20.

Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D, O'Flaherty M, Capewell S. The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21704.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Knowledge translation: Government of Canada; 2005. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html. Accessed 28 May 2017.

Global Ministerial Forum on Research for Health. The Bamako call to action on research for health. 2008. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2008/BAMAKOCALLTOACTIONFinalNov24.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2018.

World Health Assembly. Resolution 58.34 on the Ministerial Summit on Health Research. Geneva: WHO; 2005. http://www.wpro.who.int/health_research/policy_documents/ministerial_summit_on_health_research_may2005.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 25 May 2017.

Evidence-Informed Policy Network: what is EVIPNet? World Health Organization. 2016. http://www.who.int/evidence/resources/what-is-EVIPNet_20160925.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Ministerial Summit on Health Research. Mexico Statement on Health Research. 2004. http://www.wpro.who.int/health_research/policy_documents/mexico_statement_20nov04.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2017.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework--a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(4):297–304.

Flagg JL, Lane JP, Lockett MM. Need to Knowledge (NtK) Model: an evidence-based framework for generating technological innovations with socio-economic impacts. Implement Sci. 2013;8:21.

Landry R, Amara N, Lamari M. Utilization of social science research knowledge in Canada. Res Policy. 2001;30:333–49.

Hoffmann S, Thompson Klein J, Pohl C. Linking transdisciplinary research projects with science and practice at large: 1 Introducing insights from knowledge utilization. Environ Sci Policy. 2019;102:36–42.

Ward V. Why, whose, what and how? A framework for knowledge mobilisers. Evid Policy. 2017;13(3):477–97.

Lavis JN, Lomas J, Hamid M, Sewankambo NK. Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):620–8.

Cordero C, Delino R, Jeyaseelan L, Lansang MA, Lozano JM, Kumar S, et al. Funding agencies in low- and middle-income countries: support for knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(7):524–34.

El-Jardali F, Lavis J, Moat K, Pantoja T, Ataya N. Capturing lessons learned from evidence-to-policy initiatives through structured reflection. Health Syst Policy Res. 2014;12:2.

Evidence-informed Policy Network Europe. Introduction to EVIPNet Europe: conceptual background and case studies. Copenhagen: EVIPNet Europe; 2017.

Uneke CJ, Ezeoha AE, Uro-Chukwu H, Ezeonu CT, Ogbu O, Onwe F, et al. Enhancing the capacity of policy-makers to develop evidence-informed policy brief on infectious diseases of poverty in Nigeria. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(9):599–610.

Ellen ME, Lavis JN, Ouimet M, Grimshaw J, Bédard PO. Determining research knowledge infrastructure for healthcare systems: a qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:60.

Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE). ITAD; 2014. https://www.itad.com/project/evaluation-of-approaches-to-build-capacity-for-use-of-research-evidence-bcure/. Accessed 18 May 2020.

McMaster and partners receive $2 million to help achieve UN Sustainable Development Goals. McMaster University; 2019. https://brighterworld.mcmaster.ca/articles/mcmaster-and-partners-receive-2-million-to-help-achieve-un-sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed 18 May 2020.

REACH Initiative. World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/evidenceinformed/reach/en/. Accessed 18 May 2020.

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. EVIPNet Europe Strategic Plan 2013–2017. Copenhagen: WHO; 2015. http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/evidence-informed-policy-making/publications/2015/evipnet-europe-strategic-plan-20132017-2015. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Building capacity to use research evidence: data and evidence for smart policy design: Harvard Kennedy School; 2020. https://epod.cid.harvard.edu/project/building-capacity-use-research-evidence-data-and-evidence-smart-policy-design. Accessed 18 May 2020.

United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: United Nations; 2015. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Green A, Bennet S. Sound choices: enhancing capacity for evidence-informed health policy: WHO; 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43744. Accessed 25 May 2017.

Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Perry BW. Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007;85(4):729–68.

Scarlett J, Köhler K, Reinap M, Ciobanu A, Tirdea M, Koikov V, et al. Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Europe: knowledge translation success stories. Public Health Panorama. 2018;4:2.

Köhler K, Reinap M. Paving the way to sugar-sweetened beverages tax in Estonia. Public Health Panorama. 2017;3(4):633–9.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Health 2020: a European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. Geneva: WHO; 2013. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/199532/Health2020-Long.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 5 Nov 2018.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Action plan to strengthen the use of evidence, information and research for policy-making in the WHO European Region. Geneva: WHO; 2016. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/314727/66wd12e_EIPActionPlan_160528.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Vogel I, Punton M. Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) realist evaluation: stage 2 synthesis report; 2017. http://www.itad.com/knowledge-product/building-capacity-to-use-research-evaluation-bcure-realist-evaluation-stage-2-synthesis-report. Accessed 18 Aug 2020.

Vogel I, Punton M. Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE) evaluation: stage 1 synthesis report; 2016. http://www.itad.com/knowledgeproduct/building-capacity-to-use-research-evidence-bcure-evaluation-stage-1-synthesis-report/. Accessed 18 Aug 2020.

Jones H. A guide to monitoring and evaluating policy influence: Overseas Development Institute; 2011. https://www.odi.org/publications/5252-monitoring-evaluation-me-policy-influence. Accessed 25 May 2017.

Morgan-Trimmer S. Policy is political; our ideas about knowledge translation must be too. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(11):1010–1.

Bertram M, Loncarevic N, Castellani T, Valente A, Gulis G, Aro A. How could we start to develop indicators for evidence-informed policy making in public health and health promotion? Health Syst Policy Res. 2015;2(2):14.

Greenhalgh T, Raftery J, Hanney S, Glover M. Research impact: a narrative review. BMC Med. 2016;14:78.

Tudisca V, Valente A, Castellani T, Stahl T, Sandu P, Dulf D, et al. Development of measurable indicators to enhance public health evidence-informed policy-making. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):47.

Hughes A, Martin B. Enhancing impact the value of public sector R&D. CIHE-UK, IRC. 2012. https://www.ncub.co.uk/impact. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Fretheim A, Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Lewin S. SUPPORT Tools for Evidence-informed Policymaking in health 18: Planning monitoring and evaluation of policies. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):S18.

Cipher Investigators. Supporting Policy In health with Research: an Intervention Trial (SPIRIT)-protocol for a stepped wedge trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005293.

Majmood S, Hort K, Ahmed S, Mohammed S, Cravioto A. Strategies for capacity building for health research in Bangladesh: role of core funding and a common monitoring and evaluation framework. Health Syst Policy Res. 2011;9:31.

Maag S, Alexandera T, Kasec R, Hoffmann S. Indicators for measuring the contributions of individual knowledge brokers. Environ Sci Policy. 2018;89:1–9.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Panisset U, Koehlmoos TP, Alkhatib AH, Pantoja T, Singh P, Kengey-Kayondo J, et al. Implementation research evidence uptake and use for policy-making. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:20.

Aromataris E, Munn Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Accessed 18 May 2020.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Mavoa H, Waqa G, Moodie M, Kremer P, McCabe M, Snowdon W, et al. Knowledge exchange in the Pacific: The TROPIC (Translational Research into Obesity Prevention Policies for Communities) project. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:552.

Waqa G, Mavoa H, Snowdon W, Moodie M, Schultz J, McCabe M, et al. Knowledge brokering between researchers and policymakers in Fiji to develop policies to reduce obesity: a process evaluation. Implement Sci. 2013;8:74.

Waqa G, Mavoa H, Snowdon W, Moodie M, Nadakuitavuki R, Mc Cabe M, et al. Participants’ perceptions of a knowledge-brokering strategy to facilitate evidence-informed policy-making in Fiji. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:725.

Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Perrier L, Bell M, Straus S. Exploring mentorship as a strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research and practice: a scoping systematic review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:122.

ESSENCE on health research: planning, monitoring and evaluation framework for research capacity strengthening. World Health Organization; 2016. http://www.who.int/tdr/partnerships/essence/en/. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Rovan J. Composite indicators. In: Lovric M, editor. International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2011.

Curran JA, Grimshaw JM, Hayden JA, Campbell B. Knowledge translation research: the science of moving research into policy and practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2011;31(3):174–80.

McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Wilczynski NL, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Davis DA, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a Tower of Babel? Implement Sci. 2010;5:16.

Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Lewin S, Fretheim A. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 1: What is evidence-informed policymaking? Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):S1.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the librarian staff at Karolinska Institutet for their help on this project.

Funding

No funding was received for this study. Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS, BF, OB, TK and ZEK conceived and planned the study. TK conceived the original study, including the research subject and question, as part of a wider research project on the Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Europe. ZEK and TK provided conceptual and methodological guidance for the study. JS conducted the review and ZEK was the reference reviewer. TK provided resources and literature for manual addition during data collection. All authors provided input in developing the search strategy and data extraction tool and reviewed the final data results. JS prepared the first draft of the manuscript; all authors reviewed and contributed to the text. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy used to search Medline and Global Health databases. This file presents the full search strategy used to search the Medline and Global Health databases.

Additional file 2.

Study characteristics of the 32 eligible studies. This file details the complete list of included articles and includes data on the KT model of the KT infrastructure or capacity-building intervention, the country, the capacity-building level, the evaluation method used and the target audience.

Additional file 3.

Indicator data extracted from eligible studies to inform their use in evaluation. This file has a complete list of output and outcome indicators based on methods beyond expert opinion that were extracted from the eligible studies. The table includes the indicators organised by domain, the modes of verification for the indicators, the method the indicators were based on or collected with, the frequency of collection, and the study the indicator was extracted from.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Scarlett, J., Forsberg, B.C., Biermann, O. et al. Indicators to evaluate organisational knowledge brokers: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys 18, 93 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00607-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-00607-8