Abstract

Burnout in healthcare providers has impacts at the level of the individual provider, patient, and organization. While there is a substantial body of literature on burnout in healthcare providers, burnout in pediatric nurses has received less attention. This subpopulation may be unique from adult care nurses because of the specialized nature of providing care to children who are typically seen as a vulnerable population, the high potential for empathetic engagement, and the inherent complexities in the relationships with families. Thus, the aim of this scoping review was to investigate, among pediatric nurses, (i) the prevalence and/or degree of burnout, (ii) the factors related to burnout, (iii) the outcomes of burnout, and (iv) the interventions that have been applied to prevent and/or mitigate burnout. This scoping review was performed according to the PRISMA Guidelines Scoping Review Extension. CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ASSIA, and The Cochrane Library were searched on 3 November 2018 to identify relevant quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies on pediatric nurse burnout. Our search identified 78 studies for inclusion in the analysis. Across the included studies, burnout was prevalent in pediatric nurses. A number of factors were identified as impacting burnout including nurse demographics, work environment, and work attitudes. Similarly, a number of outcomes of burnout were identified including nurse retention, nurse well-being, patient safety, and patient-family satisfaction. Unfortunately, there was little evidence of effective interventions to address pediatric nurse burnout. Given the prevalence and impact of burnout on a variety of important outcomes, it is imperative that nursing schools, nursing management, healthcare organizations, and nursing professional associations work to develop and test the interventions to address key attitudinal and environmental factors that are most relevant to pediatric nurses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Burnout has been a widely studied topic of interest over the last 40 years, with significant resources devoted toward investigating its causes, impacts, and strategies for mitigation [1]. Burnout is a work outcome, defined by prolonged occupational stress in an individual that presents as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment [2].

The study of burnout in healthcare professionals is important as it has impacts at the level of the individual provider [3,4,5], the patient [6,7,8,9], and the organization [5, 10,11,12]. As nurses make up the largest group of healthcare professionals, there have been a number of studies that have explored contributing factors [13] and interventions for their burnout [14]. Pediatric nurses are a lesser-studied population, perhaps due to the relatively small number of pediatric nurses compared to general service nurses and the broader population of healthcare professionals. Burnout in pediatric nurses may be unique from adult care nurses because of the specialized nature of providing care to children who are typically seen as a vulnerable population, the high potential for empathetic engagement, and the inherent complexities in the relationships with families [15, 16]. Only one literature review could be located on the topic of pediatric nurse burnout; it mainly focused on burnout prevalence, which was found to be moderate to high [17]. Further synthesis of the literature in other domains of the topic is needed to explore factors associated with pediatric nurse burnout, the associated outcomes, and interventions.

The purpose of this scoping review is to explore what is known about pediatric nurse burnout to guide future research on this highly specialized population and, ultimately, improve both pediatric nurse and patient well-being. More specifically, the aim of this scoping review was to investigate, among pediatric nurses, (i) the prevalence and/or degree of burnout, (ii) the factors related to burnout, (iii) the outcomes of burnout, and (iv) the interventions that have been applied to prevent and/or mitigate burnout.

Methods

Protocol registration

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines scoping review extension [18]. The protocol was registered on Open Science Framework on 25 March 2019 and can be accessed at https://osf.io/5xrkg/.

Information sources and search strategy

In consultation with an experienced librarian, the following electronic databases were searched on 3 November 2018 without limitation to a publication date range in order to maximize inclusion: The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and ASSIA. All electronic database search strategies used in this review can be found in Appendix A. The term “pediatrics” was not part of the electronic database search to avoid inadvertently excluding studies that contained pediatric nurses as a non-primary subject group. The selected articles from the electronic database search were screened for inclusion of the pediatric nurse population. For the purposes of this review, the pediatric patient population is defined as newborn to age 21 as defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics, acknowledging that this age range may be slightly extended based on the country and patient needs [19].

Eligibility criteria

All qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods studies published in English that examined the prevalence and/or degree of burnout in pediatric nurses using self-identification or self-report assessment tools were included. Commentaries, letters, and editorials were excluded as these are not peer-reviewed and often referred to colloquial definitions, not the clinical definition of burnout of interest in this scoping review. Dissertations were excluded, but their corresponding publications were screened for inclusion. Conference abstracts were excluded as they are often inconsistent with their corresponding full reports [20]. Systematic or scoping reviews and meta-synthesis were excluded, but references were hand-screened for suitable studies.

Selection of sources of evidence

All citations retrieved from the databases were uploaded into Endnote with duplicates removed as per protocol [21]. The remaining citations were uploaded into Covidence for review by the research team (LB, CM, KW). Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed against the selection criteria in a blinded process by two reviewers (LB and CM). The remaining citations were then reviewed as full-text articles for inclusion against the selection criteria in a blinded process by two reviewers (LB and CM). Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (KW).

Data charting process

Data were extracted from included articles and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Extraction was performed by one researcher (LB). The following data items were extracted: title, journal, authors, year of publication, country of publication, sample size, study aim, study design, tool used to measure burnout, burnout prevalence and scores, factors that contribute to the development of burnout in pediatric nurses, factors that prevent or mitigate burnout in pediatric nurses, the impact of burnout in pediatric nurses, and interventions for pediatric nurse burnout.

Synthesis of results

A quantitative synthesis specific to the prevalence and degree of burnout was completed based on the included articles that reported raw scores for any of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) subscales. A mean score was calculated by hand across studies for each subscale, by totaling the raw scores and dividing by the total number of studies that included a raw score for that subscale. The resulting mean was also categorized as low, moderate, or high burnout based on published cutoff scores [22]. Other data were synthesized qualitatively to map current evidence available to address the remaining study aims. Aims ii and iii were analyzed using directed content analysis [23] following the themes outlined by Berta et al. [24], work environment, work attitudes, and work outcomes. Aim iv data was synthesized by grouping together similar interventions and descriptively summarizing the interventions that were effective in reducing burnout. Given that the overall purpose of the review was to explore the breadth of what is currently known about burnout in pediatric nurses, a quality assessment of individual studies was not conducted [18].

Results

Description of the search and demographics of studies included

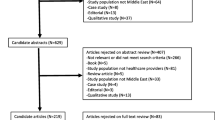

Through the initial database search, 16 909 possible papers were identified. After deduplication, 8629 titles/abstracts were screened and 1206 articles were assessed for eligibility at the level of full-text screening. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 78 studies [16, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101] were deemed relevant and retained for analysis (Fig. 1). The characteristics of included studies are provided in Table 1. Publication dates ranged from 1981 to 2018, with the majority published between 2009 and 2017. The number of pediatric nurses who participated as either a primary or sub-sample ranged from five to 3710. The most common study design was cross-sectional (n = 60), with 10 studies using multi- or mixed methods, seven using an interventional design, and one each using case-control, exploratory prospective, and longitudinal designs. Only 45 of the 78 studies reviewed used exclusive samples of pediatric nurses; the remaining studies only included pediatric nurses as a subpopulation of a larger sample. The results in this review are reported for pediatric nurse samples and sub-samples only. Almost half (46%) of the included studies were conducted in the USA, followed by Canada (n = 7), China (n = 5), Turkey (n = 3), Brazil (n = 3), Taiwan (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), and Switzerland (n = 2), plus 18 other countries where only a study was conducted. Out of the 78 studies included, 53 (68%) used some form (either complete or abbreviated) of the MBI to measure burnout (see Table 1).

Burnout prevalence and scores

Although all of the included studies measured burnout using a self-report assessment tool or binary self-identification, only 65 reported burnout scores for a sample of pediatric nurses (Table 2). In total, 53 studies used the MBI, 34 reported on the Emotional Exhaustion subscale with 24 reporting raw scores [25, 27, 29, 39, 42, 45, 48, 53, 61, 62, 72, 75, 77, 78, 84,85,86, 89, 90, 94, 97, 99, 100], and 16 reporting proportions and/or severity of those with scores indicating emotional exhaustion (e.g., low, moderate, high). The mean of the reported raw Emotional Exhaustion scores was 22.45 (SD = 6.54) which indicates moderate burnout [22]. Out of the 14 studies reporting the proportion of respondents with scores indicating high emotional exhaustion, the mean proportion was 38.7%. The mean of the reported raw Depersonalization scores [25, 29, 42, 45, 47, 48, 53, 61, 62, 72, 75, 77, 78, 84,85,86, 89, 90, 94, 97, 99, 100] was 6.95 (SD = 3.38) which indicates moderate burnout [22]. The mean of the reported raw Personal Accomplishment scores [25, 29, 42, 45, 47, 48, 53, 61, 62, 72, 75, 77, 78, 86, 89, 90, 94, 97, 99, 100] was 29.15 (SD = 11.48) which indicates high personal accomplishment [22]. The individual scores from the MBI and other measurement tools are reported for each study in Table 2.

Factors related to burnout

Of the included studies, 47 (60%) addressed factors associated with pediatric nurse burnout (Table 3). Factors related to pediatric nurse burnout were classified into the following categories: nurse demographics, work environment, work attitudes, work outcomes, and burnout interventions.

Nurse personal factors

Burnout was found to be inversely associated with age; higher burnout was also associated with low/moderate level of experience (5–10 years) [26, 32, 46, 47, 58, 71, 85, 88]. A lack of university-level education or lower self-reported levels of clinical competency were also associated with higher levels of burnout [57, 90]. Being in a nursing supervisory position had ambiguous results on impact on burnout; in some studies, holding supervisory positions correlated with higher reports of burnout while in others, the opposite effects were found [29, 33]. Nurses identifying as not being White or Asian/Pacific Islander ethnicity/race scored significantly lower on the MBI subscale of Personal Accomplishment than respondents identifying as White and Asian/Pacific Islander, and Asian/Pacific Islanders scored lower on Emotional Exhaustion than those identifying as White [36]. High neuroticism and low agreeableness [31] were both associated with higher burnout. Finally, being married had mixed results on impact on burnout, whereas in some studies, being married correlated negatively with burnout, and in others, it correlated positively [26, 36, 101].

Work environment

The work environment is defined by the conditions in which nurses work; it influences work attitudes and, in turn, work outcomes [103]. Burnout was found to be high in certain high-acuity pediatric units including emergency, medical/surgical, surgery, pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [26, 32, 35, 36, 76, 88]. Davis et al. [38] found that adult oncology nurses had higher personal accomplishment than pediatric oncology nurses while Neumann et al. [74] found nurses who care for both pediatric and adult patients had lower emotional exhaustion than those who cared for adult patents only. Conversely, Sun et al. [94] found that nurses who worked in adult obstetrics and gynecology units had more burnout than nurses who worked in pediatric units; however, Ohue et al. [78] reported the inverse. Working in hematology/oncology [88] and unit-level factors such as workload [65, 85], number of assigned patients [26], increased number of admissions, understaffing, and shifts > 8 h were associated with increased burnout [51, 92, 95, 96]. Aytekin et al. [29] found working longer years in the NICU was associated with lower levels of personal accomplishment. Brusch et al. [36] found that nurses working exclusively day shifts had higher levels of depersonalization than those working night shifts or a mix of days and nights. Favrod et al. [45] found NICU nurses reported more traumatic stressors in their working environment.

Pediatric nursing workplaces with a strict structure of rules and regulations [33] or nurse leaders who valued structure over staff considerations [41] were found to have nurses with higher burnout. Nurses who had higher perceived organizational support had lower burnout [39]. Higher burnout was generally associated with systems issues such as unreasonable policies, staffing shortages, insurance frustrations, high volumes of paperwork [65], lack of nursing supplies [36], and lack of regular staff meetings [56]. The relationship between resources and facets of burnout was mixed: Rochefort and Clarke [83] found a negative relationship between nurses’ emotional exhaustion and their rating of the adequacy of the resources available to them, while Gallagher and Gormley [46] found that even nurses who reported that support systems were in place and felt supported still were emotionally exhausted. The lack of access to work information and research information was consistently associated with higher levels of burnout [71, 91], and lower burnout was associated with increased communication [33, 36] and better work relationships [39].

Factors impacting increased pediatric nurse burnout were related to the role of the nurse in patient care activities such as decision-making/uncertainty around treatment [33, 39, 56, 76], lack of role clarity, and unclear plan of care [65]. Other factors associated with the development of burnout were related to exposure to suffering, pain, sadness, and death [65]; hopelessness [85]; providing futile care [56]; and overall moral distress [85].

Higher levels of burnout were found in nurses who cared for specific pediatric patient populations such as caring for children with cerebral palsy [97], children with cystic fibrosis [59], and babies with neonatal abstinence syndrome [73]. Another patient factor related to higher burnout involved behavioral issues from patients/families [65, 79].

Work attitudes

Work attitudes are factors that impact the positive or negative perceptions of one’s work environment [104]. Low self-compassion and low mindfulness [47] were associated with higher burnout. Co-occurring conditions with burnout such as depression [37, 63, 97], anxiety [97], and somatic work-related health problems [101] were correlated with greater burnout whereas positive psychosocial factors and coping strategies such as positive affect [30], acting with awareness [70], self-care, humor, reflection, non-work relationships, and a personal philosophy related to work were found to be associated with lower burnout [65].

Nurses’ perceived work stress was positively associated with burnout in several studies [16, 28, 63, 76, 77]. Meyer et al. [16] found that current stress exposure significantly predicted higher levels of burnout after controlling for pre-existing stress exposure, and Holden et al. [51] found that burnout was positively associated with mental workload. Oehler and Davidson [76] found perceived workload made a significant contribution to feelings of burnout. Job satisfaction was also found to be negatively associated with burnout [26, 29, 39, 43, 47, 51, 67].

Work outcomes

Work outcomes refer to occupational performance factors that are influenced by work attitudes and the work environment [24]. Nine studies examined work outcomes associated with burnout including nurse retention, nurse well-being, patient safety, and patient-family satisfaction (Table 4). An increase in burnout was associated with nurses considering a career change [37], decreased quality of life [29], tiredness [89], and feeling negatively toward their teammates and the impact of their work [37]. Work-associated compassion fatigue [16, 66], secondary traumatic stress [48, 58], and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [37, 60, 70] were all found to be associated with pediatric nurse burnout. However, Li et al. [60] report that high group cohesion may prevent pediatric nurses from developing burnout from PTSD by protecting nurses from the impacts of negative outcomes. Nurse burnout was found to be negatively associated with the safety climate of the hospital in which they work [27, 39] and positively associated with higher infection rates when nurses were feeling overworked [96]. Moussa and Mahmood [71] found that as nurses’ personal accomplishment increased, so did patients’ mothers’ satisfaction with meeting their child’s care needs in the hospital.

Burnout interventions

Seven of the 78 studies included interventions to mitigate burnout (Table 5). Interventions included coping workshops [42], mindfulness activities [47, 68, 70], workshops to improve knowledge/understanding of their patient population [81, 85], and clinical supervision [50]. Only three of the seven interventions studied provided varying positive impacts on burnout scores [42, 70, 85]. An in-person day-long retreat resulted in a significant improvement in emotional exhaustion for pediatric nurses. The intervention involved didactic and hands-on trauma, adaptive grief, and coping strategies; half of the subjects were also randomized to a booster session 6 months later [42]. Another intervention involved a 90-min interactive module on clinical skills surrounding the management of pediatric pain and resulted in a significant decrease in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization [85]. Finally, the third study of smartphone-delivered mindfulness interventions showed a marginal decrease in burnout compared to nurses receiving traditional mindfulness interventions [70].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that focuses on what is known about pediatric nurse burnout. Burnout was measured with a variety of instruments and interpretations, thereby making score comparisons a challenge. Even in those studies that used the MBI, the most commonly used burnout measurement [105], variations of the tool were applied, as were diverse subscale cutoff scores. Similar challenges in synthesizing extremely heterogeneous burnout data were echoed in a 2018 JAMA review of the prevalence of burnout among different types of physicians [106]. Of the MBI Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization subscale results that were synthesized, the results showed moderate scores indicating a significant level of burnout in pediatric nurses. Personal Accomplishment subscale results were high, perhaps indicating a factor of pediatric nursing that increases resilience despite moderate burnout in other domains. In studies that compared nurses who work in pediatric units to other in-patient units, burnout results were mixed [26, 32, 35, 36, 38, 74, 78, 94]. The majority of the included studies identified correlational relationships using cross-sectional study designs, which limited causal inferences. Study designs, such as longitudinal approaches, would allow for causal inference and in-depth analysis of this phenomenon in this unique population.

Nurse personal factors

Pediatric nurse demographic factors that are associated with burnout, such as age, work experience, and level of education, have been a common area of studied burnout associations across other healthcare populations. Similar burnout associations were found in research studying healthcare providers caring for adults such as younger age (< 31 years) [107, 108] and years of experience (> 7 years) [109]. It is likely that nurses new to the profession are younger, are experiencing the challenges of the nursing profession for the first time, and are less likely to have well-developed skills for resiliency. Given that the start of nurses’ careers is a vulnerable stage for burnout, nursing schools and orientation programs may be well-positioned to highlight burnout prevention and mitigation strategies with students and new hires [107]. Personality traits such as high neuroticism and low agreeableness were found to be associated with pediatric nurse burnout [31]. These results have been supported in other nurse and physician populations, along with conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness contributing to lower levels of burnout [110,111,112,113]. Although personality traits appear to have significant correlations with healthcare provider burnout, targeting modulation of personality traits as a mitigation strategy for burnout may be a high-cost, low-yield strategy.

It has been suggested that healthcare provider burnout is not a failure on the part of the individual, rather it is a culmination of impacts stemming from the work environment and the healthcare system as a whole [114]. Responsibility, then, is thought to lie within the individual, the organization, and the profession in general.

Work environment

Job demands and resource variables in pediatric nursing lead to increased burnout, work-life interference, psychosomatic complaints, and intent to leave; these associations are also represented in adult nursing literature [102, 115], including associations with excessive workload, number of assigned patients, admissions, understaffing, and longer shifts [116,117,118,119]. Although Bursch et al. [36] found that pediatric nurses who worked straight day shifts had higher depersonalization than those who worked mixed shifts or just night shifts, Poncet et al. [108] found that working more night shifts was associated with higher burnout in adult critical care nurses. Day shift nurses have potentially more strenuous workloads as patients are more wakeful, have diagnostic tests, or consulting services visiting; however, night shifts could be perceived as more strenuous as it requires the provider to work against their natural circadian rhythm and less support staff are available [120]. These results may also be dependent on individuals’ preference and the specific unit on which they work.

Systems issues such as overwhelming clerical work, administrative, and resource issues have impacts on provider burnout in both the pediatric nurse and general physician populations [36, 56, 65, 121]. Poor leadership is associated with pediatric nurse burnout as identified by Bilial and Ahmed [33] and Druxbury et al. [41]; this relationship is echoed in research with physicians, nurses, and allied health [122]. In pediatric nurses [39], increased perception of organizational support is associated with lower burnout; this association is supported in general nursing populations [119, 123]. In all populations, the support a healthcare provider perceives they get from the organization is predictive of their level of organizational commitment. When healthcare providers perceive that they have high organizational support, they will exhibit greater organizational citizenship behavior, which are extra-role tasks that ultimately improve the organization [124]. Burnout itself results in reduced organizational commitment on the part of the healthcare provider [125].

The experience of witnessing patient suffering and death [65, 122], uncertainty around plan/utility of care [15, 56, 126], moral distress [15, 85], and behavioral issues with patient families (e.g., aggressive patients/families) [65, 79, 127] were found to be significant factors that contributed to burnout in both pediatric nurses and general population physicians and nurses.

Work attitudes

As might be expected, optimism, self-efficiency, resilience, and positive coping strategies are supported as inversely related to burnout in broader nursing populations [128,129,130]. The identification and treatment of burnout is particularly important to consider in light of the evidence that burnout is inversely related to job satisfaction and burnout is a contagious phenomenon between nurses; therefore, early intervention is essential to prevent transmission among staff [131,132,133].

Work outcomes

The association between burnout and patient satisfaction and intent to leave has been reported in non-pediatric nurse populations as well [5, 6, 115, 134,135,136]. It is likely that as nurses become increasingly burned out their satisfaction with their jobs decreases and their desire to leave their position increases. This linkage highlights the importance of addressing nurse burnout in the organization to retain staff and reduce the financial and tacit knowledge losses associated with high nurse turnover.

Higher work-related burnout is also associated with mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression in pediatric nurses; this is represented in several studies of other healthcare provider populations [113, 137,138,139,140]. However, the majority of these associations are correlational; thus, they are left open for further assessment if they impact the development of burnout or if burnout impacted their development. Further research is needed to confirm causal, directional effects.

The relationship of increased clinician burnout and decreased patient safety has been supported in additional studies of healthcare provider burnout [7, 141]. As clinician burnout increases, the detachment from patients and their work does too, which may contribute to negative attitudes toward patient safety, incomplete infection control practices, and decreased patient engagement [7, 141]. Reducing burnout has the potential to impact patient safety; the Quadruple Aim of Healthcare hopes to improve patient outcomes, such as safety, through the addition of clinician well-being as a primary aim in the model [142].

Interventions

Although only seven of the studies analyzed in this review included interventions, there is modest evidence on the efficacy of burnout interventions in the broader healthcare provider population. Similar to the results of Hallberg [50], a study of Swedish district nurses showed no impact of clinical supervision on burnout [143]. While Morrison Wylde et al. [70] found a marginal improvement in pediatric nurse burnout with smartphone-based intervention vs. traditional mindfulness interventions, studies investigating mindfulness interventions in other healthcare populations reported mixed results [144,145,146,147]. Similar to pediatric nurses [84], social workers showed a significant decrease in burnout after attending skills development courses [148] suggesting that improving clinical knowledge and skills may reduce burnout. This is supported by the finding that pediatric nurses with lower clinical competency and education level have increased burnout [57, 90]. Although Edmonds et al. [42] showed significant decreases in pediatric nurse burnout using in-person trauma, adaptive grief, and coping sessions with follow-up, similar sessions have shown mixed results in other healthcare provider populations [149,150,151]. More research is needed to identify reliable interventions for pediatric nurse burnout that can be pre-emptively and routinely implemented by nursing schools and healthcare organizations.

Study limitations

The search strategy was limited to publications in English; thus, potentially relevant studies in other languages were excluded. Gray literature was not included; thus, informal annual surveys conducted at various healthcare institutions may have been missed; however, this was outweighed by the desire to only include peer-reviewed literature to ensure the quality of data reviewed [152]. Third, the definition of “nurses” varies internationally as does their required education and scope of practice; however, the slight variations were outweighed by the need to include thorough, culturally diverse research. Finally, the extreme heterogeneity of the burnout measurement tools and their application and interpretation inhibited the comparison of results across studies.

Conclusion

Our scoping review showed inconsistent measurement and interpretation of pediatric nurse burnout scores. Factors associated with pediatric nurse burnout were similar to those found in other healthcare professional groups and can be separated into the domains of nurse personal factors, work environment, work attitudes, and work outcomes. Only 45 of the 78 studies reviewed studied exclusive populations of pediatric nurses, and most associations identified were correlational. Few interventions to prevent or mitigate pediatric nurse burnout have been undertaken, and the results were mixed, at best. Further studies using mixed methods are needed to expand on these results and incorporate the direct feedback of the nurses. Additional research is needed to develop and test interventions for pediatric nurse burnout. The improvement of pediatric nurse burnout has the potential to improve nurse well-being and, ultimately, patient care.

Availability of data and materials

The complete list of articles used as data in this review is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

References

Leiter MP, Maslach C, Schaufeli WB. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2009;14(3):204–20.

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113.

Wang S, Yao L, Li S, Liu Y, Wang H, Sun Y. Sharps injuries and job burnout: a cross-sectional study among nurses in China. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;14(3):332–8.

Han SS, Han JW, An YS, Lim SH. Effects of role stress on nurses’ turnover intentions: the mediating effects of organizational commitment and burnout. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2015;12(4):287–96.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–46.

Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke SP, Vargas D. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2004;42(2 Suppl):II57–66.

Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(6):486–90 [erratum appears in am J infect control. 2012 Sep;40(7):680].

Manomenidis G, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. Job burnout reduces hand hygiene compliance among nursing staff. J Patient Saf. 2017;13:13.

Johnson J, Louch G, Dunning A, Johnson O, Grange A, Reynolds C, et al. Burnout mediates the association between depression and patient safety perceptions: a cross-sectional study in hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(7):1667–80.

Chiu S-F, Tsai M-C. Relationships among burnout, job involvement, and organizational citizenship behavior. J Psychol. 2006;140(6):517–30.

Zhou Y, Lu J, Liu X, Zhang P, Chen W. Effects of core self-evaluations on the job burnout of nurses: the mediator of organizational commitment. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95975.

Gabel Shemueli R, Dolan SL, Suarez Ceretti A, Nunez Del Prado P. Burnout and engagement as mediators in the relationship between work characteristics and turnover intentions across two Ibero-American nations. Stress Health. 2016;32(5):597–606.

Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Oldenburg B. Burnout in relation to specific contributing factors and health outcomes among nurses: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(6):2214–40.

Nowrouzi B, Lightfoot N, Larivière M, Carter L, Rukholm E, Schinke R, et al. Occupational stress management and burnout interventions in nursing and their implications for healthy work environments: a literature review. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(7):308–15.

Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, Parshuram CS. Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners: a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(8):e318–e26.

Meyer RM, Li A, Klaristenfeld J, Gold JI. Pediatric novice nurses: examining compassion fatigue as a mediator between stress exposure and compassion satisfaction, burnout, and job satisfaction. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(1):174–83.

Pradas-Hernandez L, Ariza T, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Albendin-Garcia L, De la Fuente EI, Canadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence of burnout in paediatric nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195039.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. The PRISMA-ScR statement. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Hardin AP, Hackell JM. Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20172151.

Li G, Abbade LPF, Nwosu I, Jin Y, Leenus A, Maaz M, et al. A scoping review of comparisons between abstracts and full reports in primary biomedical research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):181.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–3.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual, vol. iv. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. p. 52.

Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42–55.

Berta W, Laporte A, Perreira T, Ginsburg L, Dass AR, Deber R, et al. Relationships between work outcomes, work attitudes and work environments of health support workers in Ontario long-term care and home and community care settings. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):15.

Adwan JZ. Pediatric nurses’ grief experience, burnout and job satisfaction. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29(4):329–36.

Akman O, Ozturk C, Bektas M, Ayar D, Armstrong MA. Job satisfaction and burnout among paediatric nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(7):923–33.

Alves DF, Guirardello EB. Safety climate, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction among Brazilian paediatric professional nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(3):328–35.

Amin AA, Vankar JR, Nimbalkar SM, Phatak AG. Perceived stress and professional quality of life in neonatal intensive care unit nurses in Gujarat. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82(11):1001–5.

Aytekin A, Yilmaz F, Kuguoglu S. Burnout levels in neonatal intensive care nurses and its effects on their quality of life. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2013;31(2):39–47.

Barr P. Personality traits, state positive and negative affect, and professional quality of life in neonatal nurses. J Obst Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;22:22.

Barr P. The five-factor model of personality, work stress and professional quality of life in neonatal intensive care unit nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(6):1349–58.

Berger J, Polivka B, Smoot EA, Owens H. Compassion fatigue in pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(6):e11–7.

Bilal A, Ahmed HM. Organizational structure as a determinant of job burnout. Workplace Health Saf. 2017;65(3):118–28.

Bourbonnais R, Comeau M, Vezina M, Dion G. Job strain, psychological distress, and burnout in nurses. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34(1):20–8.

Branch C, Klinkenberg D. Compassion fatigue among pediatric healthcare providers. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2015;40(3):160–6 quiz E13–4.

Bursch B, Emerson ND, Arevian AC, Aralis H, Galuska L, Bushman J, et al. Feasibility of online mental wellness self-assessment and feedback for pediatric and neonatal critical care nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;43:62–8.

Czaja AS, Moss M, Mealer M. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among pediatric acute care nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012;27(4):357–65.

Davis S, Lind BK, Sorensen C. A comparison of burnout among oncology nurses working in adult and pediatric inpatient and outpatient settings. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(4):E303–11.

Dos Santos Alves DF, da Silva D, de Brito Guirardello E. Nursing practice environment, job outcomes and safety climate: a structural equation modelling analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(1):46–55.

Downey V, Bengiamin M, Heuer L, Juhl N. Dying babies and associated stress in NICU nurses. Neonatal Netw. 1995;14(1):41–6.

Duxbury ML, Armstrong GD, Drew DJ, Henly SJ. Head nurse leadership style with staff nurse burnout and job satisfaction in neonatal intensive care units. Nurs Res. 1984;33(2):97–101.

Edmonds C, Lockwood GM, Bezjak A, Nyhof-Young J. Alleviating emotional exhaustion in oncology nurses: an evaluation of Wellspring’s “Care for the Professional Caregiver Program”. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1):27–36.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hutchinson AM, Scott S, Cummings GG, Kang SH, et al. Assessment of variation in the Alberta context tool: the contribution of unit level contextual factors and specialty in Canadian pediatric acute care settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):251.

Faller MS, Gates MG, Georges JM, Connelly CD. Work-related burnout, job satisfaction, intent to leave, and nurse-assessed quality of care among travel nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41(2):71–7.

Favrod C, Jan du Chene L, Martin Soelch C, Garthus-Niegel S, Tolsa JF, Legault F, et al. Mental health symptoms and work-related stressors in hospital midwives and NICU nurses: a mixed methods study. Front Psychiatry Front Res Found. 2018;9:364.

Gallagher R, Gormley DK. Perceptions of stress, burnout, and support systems in pediatric bone marrow transplantation nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(6):681–5.

Gauthier T, Meyer RML, Grefe D, Gold JI. An on-the-job mindfulness-based intervention for pediatric ICU nurses: a pilot. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(2):402–9.

Gunusen NP, Wilson M, Aksoy B. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout among Muslim nurses caring for chronically ill children in a Turkish hospital. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29(2):146–54.

Habadi AI, Alfaer SS, Shilli RH, Habadi MI, Suliman SM, Al-Aslany SJ, et al. The prevalence of burnout syndrome among nursing staff working at king Abdulaziz University hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2017. Divers Equality Health Care. 2018;15(3):122.

Hallberg IR. Systematic clinical supervision in a child psychiatric ward: satisfaction with nursing care, tedium, burnout, and the nurses’ own report on the effects of it. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1994;8(1):44–52.

Holden RJ, Scanlon MC, Patel NR, Kaushal R, Escoto KH, Brown RL, et al. A human factors framework and study of the effect of nursing workload on patient safety and employee quality of working life. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):15–24.

Hsu HY, Chen SH, Yu HY, Lou JH. Job stress, achievement motivation and occupational burnout among male nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(7):1592–601.

Hylton Rushton C, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412–21.

Jacobs LM, Nawaz MK, Hood JL, Bae S. Burnout among workers in a pediatric health care system. Workplace Health Saf. 2012;60(8):335–44.

Kase SM, Waldman ED, Weintraub AS. A cross-sectional pilot study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in pediatric palliative care providers in the United States. Palliat Supportive Care. 2018;55(2):1–7.

Klein SD, Bucher HU, Hendriks MJ, Baumann-Holzle R, Streuli JC, Berger TM, et al. Sources of distress for physicians and nurses working in Swiss neonatal intensive care units. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14477.

Koivula M, Paunonen M, Laippala P. Burnout among nursing staff in two Finnish hospitals. J Nurs Manag. 2000;8(3):149–58.

Latimer M, Jackson PL, Eugene F, MacLeod E, Hatfield T, Vachon-Presseau E, et al. Empathy in paediatric intensive care nurses part 1: behavioural and psychological correlates. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2676–85.

Lewiston NJ, Conley J, Blessing-Moore J. Measurement of hypothetical burnout in cystic fibrosis caregivers. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1981;70(6):935–9.

Li A, Early SF, Mahrer NE, Klaristenfeld JL, Gold JI. Group cohesion and organizational commitment: protective factors for nurse residents’ job satisfaction, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout. J Prof Nurs. 2014;30(1):89–99.

Liakopoulou M, Panaretaki I, Papadakis V, Katsika A, Sarafidou J, Laskari H, et al. Burnout, staff support, and coping in pediatric oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(2):143–50.

Lin F, St John W, McVeigh C. Burnout among hospital nurses in China. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(3):294–301.

Lin TC, Lin HS, Cheng SF, Wu LM, Ou-Yang MC. Work stress, occupational burnout and depression levels: a clinical study of paediatric intensive care unit nurses in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(7–8):1120–30.

Liu X, Zheng J, Liu K, Baggs JG, Liu J, Wu Y, et al. Hospital nursing organizational factors, nursing care left undone, and nurse burnout as predictors of patient safety: a structural equation modeling analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;86:82–9.

Maytum JC, Heiman MB, Garwick AW. Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18(4):171–9.

Meadors P, Lamson A, Swanson M, White M, Sira N. Secondary traumatization in pediatric healthcare providers: compassion fatigue, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. Omega. 2009;60(2):103.

Messmer PR, Bragg J, Williams PD. Support programs for new graduates in pediatric nursing. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2011;42(4):182–92.

Moody K, Kramer D, Santizo RO, Magro L, Wyshogrod D, Ambrosio J, et al. Helping the helpers: mindfulness training for burnout in pediatric oncology--a pilot program. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(5):275–84.

Morelius E, Gustafsson PA, Ekberg K, Nelson N. Neonatal intensive care and child psychiatry inpatient care: do different working conditions influence stress levels? Nurs Res Pract. 2013;2013:761213.

Morrison Wylde C, Mahrer NE, Meyer RML, Gold JI. Mindfulness for novice pediatric nurses: smartphone application versus traditional intervention. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:205–12.

Moussa I, Mahmood E. The relationship between nurses’ burnout and mothers’ satisfaction with pediatric nursing care. Int J Curr Res. 2013;5(7):1902–7.

Mudallal RH, Othman WM, Al Hassan NF. Nurses’ burnout: the influence of leader empowering behaviors, work conditions, and demographic traits. Inquiry. 2017;54:46958017724944.

Murphy-Oikonen J, Brownlee K, Montelpare W, Gerlach K. The experiences of NICU nurses in caring for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal Netw. 2010;29(5):307–13.

Neumann JL, Mau LW, Virani S, Denzen EM, Boyle DA, Boyle NJ, et al. Burnout, moral distress, work-life balance, and career satisfaction among hematopoietic cell transplantation professionals. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(4):849–60.

Nguyen HTT, Kitaoka K, Sukigara M, Thai AL. Burnout study of clinical nurses in Vietnam: development of job burnout model based on Leiter and Maslach’s theory. Asian Nurs Res. 2018;12(1):42–9.

Oehler JM, Davidson MG. Job stress and burnout in acute and nonacute pediatric nurses. Am J Crit Care. 1992;1(2):81–90.

Oehler JM, Davidson MG, Starr LE, Lee DA. Burnout, job stress, anxiety, and perceived social support in neonatal nurses. Heart Lung. 1991;20(5 Pt 1):500–5.

Ohue T, Moriyama M, Nakaya T. Examination of a cognitive model of stress, burnout, and intention to resign for Japanese nurses. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2011;8(1):76–86.

Pagel I, Wittmann ME. Relationship of burnout to personal and job-related variables in acute-care pediatric settings. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1986;9(2):131–43.

Profit J, Sharek PJ, Amspoker AB, Kowalkowski MA, Nisbet CC, Thomas EJ, et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(10):806–13.

Richter LM, Rochat TJ, Hsiao C, Zuma TH. Evaluation of a brief intervention to improve the nursing care of young children in a high HIV and AIDS setting. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:647182.

Robins PMP, Meltzer LP, Zelikovsky NP. The experience of secondary traumatic stress upon care providers working within a children’s hospital. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24(4):270.

Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2213–24.

Rodrigues NP, Cohen LL, McQuarrie SC, Reed-Knight B. Burnout in nurses working with youth with chronic pain: a pilot intervention. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43(4):382–91.

Rodrigues NP, Cohen LL, Swartout KM, Trotochaud K, Murray E. Burnout in nurses working with youth with chronic pain: a mixed-methods analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43(4):369–81.

Rodríguez-Rey R, Palacios A, Alonso-Tapia J, Pérez E, Álvarez E, Coca A, et al. Burnout and posttraumatic stress in paediatric critical care personnel: prediction from resilience and coping styles. Aust Crit Care. 2019;32(1):46–53.

Roney LN, Acri MC. The cost of caring: an exploration of compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and job satisfaction in pediatric nurses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;40:74–80.

Sekol M, Kim S. Job satisfaction, burnout, and stress among pediatric nurses in various specialty units at an acute care hospital. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2014;4(12):115–24.

Skorobogatova N, Zemaitiene N, Smigelskas K, Tameliene R. Professional burnout and concurrent health complaints in neonatal nursing. Open Med. 2017;12:328–34.

Soroush F, Zargham-Boroujeni A, Namnabati M. The relationship between nurses’ clinical competence and burnout in neonatal intensive care units. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21(4):424–9.

Squires JE, Estabrooks CA, Scott SD, Cummings GG, Hayduk L, Kang SH, et al. The influence of organizational context on the use of research by nurses in Canadian pediatric hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):351.

Stimpfel AW, Lake ET, Barton S, Gorman KC, Aiken LH. How differing shift lengths relate to quality outcomes in pediatrics. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(2):95–100.

Sun JW, Lin PZ, Zhang HH, Li JH, Cao FL. A non-linear relationship between the cumulative exposure to occupational stressors and nurses’ burnout and the potentially emotion regulation factors. J Ment Health. 2017;27(5):1–7.

Sun WY, Ling GP, Chen P, Shan L. Burnout among nurses in the People’s Republic of China. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1996;2(4):274–9.

Tawfik DS, Phibbs CS, Sexton JB, Kan P, Sharek PJ, Nisbet CC, et al. Factors associated with provider burnout in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):05.

Tawfik DS, Sexton JB, Kan P, Sharek PJ, Nisbet CC, Rigdon J, et al. Burnout in the neonatal intensive care unit and its relation to healthcare-associated infections. J Perinatol. 2017;37(3):315–20.

Vicentic S, Sapic R, Damjanovic A, Vekic B, Loncar Z, Dimitrijevic I, et al. Burnout of formal caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2016;53(2):10–5.

Paula Vega V, Rina González R, Natalie Santibáñez G, Camila Ferrada M, Javiera Spicto O, Antonia Sateler V, et al. Supporting in grief and burnout of the nursing team from pediatric units in Chilean hospitals. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2017;51:1–6.

Watson P, Feld A. Factors in stress and burnout among paediatric nurses in a general hospital. Nurs Prax N Z. 1996;11(3):38–46.

Yao Y, Zhao S, Gao X, An Z, Wang S, Li H, et al. General self-efficacy modifies the effect of stress on burnout in nurses with different personality types. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):667.

Zanatta AB, Lucca SR. Prevalence of burnout syndrome in health professionals of an onco-hematological pediatric hospital. Revista Da Escola de Enfermagem Da Usp. 2015;49(2):253–60.

Jourdain G, Chenevert D. Job demands-resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(6):709–22.

Perreira TA, Berta W, Laporte A, Ginsburg L, Deber R, Elliott G, et al. Shining a light: examining similarities and differences in the work psychology of health support workers employed in long-term care and home and community care settings. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;38(11):0733464817737622.

Pinder CC. Work motivation in organizational behavior: psychology press; 2014.

Cartwright S, Cooper CL. The Oxford handbook of organizational well-being. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. Available from: http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211913.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199211913

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–50.

Chen SM, McMurray A. “Burnout” in intensive care nurses. J Nurs Res. 2001;9(5):152–64.

Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, Pochard F, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):698–704.

Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Job satisfaction and burnout among intensive care unit nurses and physicians. Crit Care Res Pract. 2013;2013:786176.

Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: a systematic review of 25 years of research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(2):649–61.

Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169–77.

McManus IC, Keeling A, Paice E. Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: a twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Med. 2004;2:29.

De la Fuente-Solana EI, Gomez-Urquiza JL, Canadas GR, Albendin-Garcia L, Ortega-Campos E, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Burnout and its relationship with personality factors in oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;30:91–6.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US Population. JAMA Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–85.

Moloney W, Boxall P, Parsons M, Cheung G. Factors predicting registered nurses’ intentions to leave their organization and profession: a job demands-resources framework. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(4):864–75.

Dall Ora C, Griffiths P, Ball J, Simon M, Aiken LH. Association of 12 h shifts and nurses’ job satisfaction, burnout and intention to leave: findings from a cross-sectional study of 12 European countries. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008331.

Galvan ME, Vassallo JC, Rodriguez SP, Otero P, Montonati MM, Cardigni G, et al. Professional burnout in pediatric intensive care units in Argentina. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2012;110(6):466–73.

Garcia-Izquierdo M, Rios-Risquez MI. The relationship between psychosocial job stress and burnout in emergency departments: an exploratory study. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(5):322–9.

Spence Laschinger HK, Grau AL, Finegan J, Wilk P. Predictors of new graduate nurses’ workplace well-being: testing the job demands-resources model. Health Care Manag Rev. 2012;37(2):175–86.

Lindborg C, Davidhizar R. Is there a difference in nurse burnout on the day or night shift? Health Care Superv. 1993;11(3):47–52.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901–2.

Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Ripp J, Murphy ML, Sandborg C, Bohman B. Building a program on well-being: key design considerations to meet the unique needs of each organization. Acad Med. 2018;21:21.

Hunsaker S, Chen HC, Maughan D, Heaston S. Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(2):186–94.

Cropanzano R, Mitchell M. Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag. 2005;31(6):874–900.

Leiter MP, Maslach C. The impact of interpersonal environment on burnout and organizational commitment. J Organ Behav (1986–1998). 1988;9(4):297.

Teixeira C, Ribeiro O, Fonseca AM, Carvalho AS. Burnout in intensive care units - a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: a descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013;13(1):38.

Merecz D, Drabek M, Moscicka A. Aggression at the workplace--psychological consequences of abusive encounter with coworkers and clients. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2009;22(3):243–60.

Chang Y, Chan HJ. Optimism and proactive coping in relation to burnout among nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(3):401–8.

Ding Y, Yang Y, Yang X, Zhang T, Qiu X, He X, et al. The mediating role of coping style in the relationship between psychological capital and burnout among Chinese nurses. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122128.

Laschinger HK, Grau AL. The influence of personal dispositional factors and organizational resources on workplace violence, burnout, and health outcomes in new graduate nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(3):282–91.

Bakker AB, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(3):276–87.

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–93.

McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. 2011;30(2):202–10.

Cameron SJ, Horsburgh ME, Armstrong-Stassen M. Job satisfaction, propensity to leave and burnout in RNs and RNAs: a multivariate perspective. Can J Nurs Adm. 1994;7(3):43–64.

Leiter MP, Maslach C. Nurse turnover: the mediating role of burnout. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(3):331–9.

Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36–41.

Colville GA, Smith JG, Brierley J, Citron K, Nguru NM, Shaunak PD, et al. Coping with staff burnout and work-related posttraumatic stress in intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(7):e267–e73.

Creedy DK, Sidebotham M, Gamble J, Pallant J, Fenwick J. Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):13.

Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, Gonzalez AD, Gabani FL, Andrade SM. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185781.

Vasconcelos EM, Martino MMF, Franca SPS. Burnout and depressive symptoms in intensive care nurses: relationship analysis. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(1):135–41.

Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1573.

Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–6.

Palsson MB, Hallberg IR, Norberg A, Bjorvell H. Burnout, empathy and sense of coherence among Swedish district nurses before and after systematic clinical supervision. Scand J Caring Sci. 1996;10(1):19–26.

Barbosa P, Raymond G, Zlotnick C, Wilk J, Toomey R III, Mitchell J III. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training is associated with greater empathy and reduced anxiety for graduate healthcare students. Educ Health. 2013;26(1):9–14.

de Vibe M, Solhaug I, Tyssen R, Friborg O, Rosenvinge JH, Sørlie T, et al. Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):107.

Garneau K, Hutchinson T, ZHAO Q, Dobkin P. Cultivating person centered medicine in future physicians. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2013;1(2):468–77.

Goodman MJ, Schorling JB. A mindfulness course decreases burnout and improves well-being among healthcare providers. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(2):119–28.

Cohen M, Gagin R. Can skill-development training alleviate burnout in hospital social workers? Soc Work Health Care. 2005;40(4):83–97.

Kravits K, McAllister-Black R, Grant M, Kirk C. Self-care strategies for nurses: a psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(3):130–8.

Sallon S, Katz-Eisner D, Yaffe H, Bdolah-Abram T. Caring for the caregivers: results of an extended, five-component stress-reduction intervention for hospital staff. Behav Med. 2017;43(1):47–60.

Wlodarczyk N. The effect of a group music intervention for grief resolution on disenfranchised grief of hospice workers. Prog Palliat Care. 2013;21(2):97–106.

Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS. Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. Int J Manag Rev. 2017;19(4):432–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge librarian Mikaela Gray for her assistance with the search strategy development. Kristin Cleverley was supported by the CAMH Chair in Mental Health Nursing Research while writing this article.

Funding

This paper is part of the doctoral work of the primary author who is funded by the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing, University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and drafting and finalizing the manuscript. WB and KC were involved in data interpretation and substantively revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. CM was involved in the data collection (title, abstract, and full-text screening) and substantively revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KW was involved in the study design, data interpretation, and substantively revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree both to be personally accountable for their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. None of the authors have any competing interests as outlined by BioMed Central.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K. et al. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health 18, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-0451-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-0451-8