Abstract

Background

More than 60% of the world’s rural population live in the Asia-Pacific region. Of these, more than 90% reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Asia-Pacific LMICs rural populations are more impoverished and have poorer access to medical care, placing them at greater risk of poor health outcomes. Understanding factors associated with doctors working in rural areas is imperative in identifying effective strategies to improve rural medical workforce supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs.

Method

We performed a scoping review of peer-reviewed and grey literature from Asia-Pacific LMICs (1999 to 2019), searching major online databases and web-based resources. The literature was synthesized based on the World Health Organization Global Policy Recommendation categories for increasing access to rural health workers.

Result

Seventy-one articles from 12 LMICs were included. Most were about educational factors (82%), followed by personal and professional support (57%), financial incentives (45%), regulatory (20%), and health systems (13%). Rural background showed strong association with both rural preference and actual work in most studies. There was a paucity in literature on the effect of rural pathway in medical education such as rural-oriented curricula, rural clerkships and internship; however, when combined with other educational and regulatory interventions, they were effective. An additional area, atop of the WHO categories was identified, relating to health system factors, such as governance, health service organization and financing. Studies generally were of low quality—frequently overlooking potential confounding variables, such as respondents’ demographic characteristics and career stage—and 39% did not clearly define ‘rural’.

Conclusion

This review is consistent with, and extends, most of the existing evidence on effective strategies to recruit and retain rural doctors while specifically informing the range of evidence within the Asia-Pacific LMIC context. Evidence, though confined to 12 countries, is drawn from 20 years’ research about a wide range of factors that can be targeted to strengthen strategies to increase rural medical workforce supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs. Multi-faceted approaches were evident, including selecting more students into medical school with a rural background, increasing public-funded universities, in combination with rural-focused education and rural scholarships, workplace and rural living support and ensuring an appropriately financed rural health system. The review identifies the need for more studies in a broader range of Asia-Pacific countries, which expand on all strategy areas, define rural clearly, use multivariate analyses, and test how various strategies relate to doctor’s career stages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuing to strengthen the rural health workforce is crucial as part of building universal health coverage and achieving Sustainable Development Goals [1,2,3,4]. Even when rural people, who account for nearly half of the world’s population, are covered by universal health insurance, service coverage may be poor without a sufficient number of skilled local health workers [3, 5].

Higher doctor-to-population ratios correlate with lower maternal, child, and neonatal mortality [6, 7] and lower all-cause morbidity and mortality rates [8, 9], suggesting that access to tertiary qualified doctors is essential. Countries at all levels of socioeconomic development are investing in strategies to improve the supply and retention of qualified doctors in rural areas. High-income countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia have implemented numerous policies and published extensively about various interventions, including financial incentives, rural education pathways, regulatory, and personal and professional support strategies to address rural doctor shortages [10,11,12,13,14,15]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), stand-alone policies of compulsory rural healthcare-professional placements have also been implemented [16, 17]. However, the range of research informing how to improve access to qualified rural doctors in LMICs remains to be summarized. An additional quality issue is the lack of evidence relating to doctors at various career stages, since medical workforce dynamics may change by stage professional development [18].

The Asia-Pacific region is home to more than half of the global population, with approximately 98% of the Asia-Pacific population living in 29 LMICs, and just over half of these LMIC populations living rurally [19]. Doctor-to-population ratios in Asia-Pacific LMICs are well below the World Health Organization (WHO)’s benchmark of 1.15-to-1000 population [19], which is essential to achieve its Sustainable Development Goals [1]. Thus, it is critical to understand the effectiveness of strategies implemented to increase rural medical workforce supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs.

With this background in mind, this review summarizes and synthesizes existing evidence about factors associated with preferences and actual work locations of medical students and doctors in Asia-Pacific LMICs. This is done with a view to identifying effective strategies for recruiting and retaining doctors in rural areas. Additional aims are to describe how studies define rural or remote and to determine the spread of evidence by career stage, so as to inform how to target strategies better.

Methods

Nature of review

The scoping review method was used as it was most relevant to answering the primary research question about the range and extent of existing evidence. Scoping reviews, unlike traditional systematic reviews, place less emphasis on the critical appraisal of the included evidence, thus allowing the inclusion of a broader range of literature potentially relevant to capturing emerging evidence in Asia-Pacific LMICs [20]. The protocol for this review was developed iteratively by the authorship team according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-Scr) [21].

Search strategy

The authors, with assistance of an experienced librarian, developed a Boolean string from key search terms (Table 1) and tested hits against ten key articles known to the first author with 100% sensitivity. Included were terms that covered LMICs, sub-regions and country groups in the Asia-Pacific as at 2019, using the World Bank 2019 definition of Asia-Pacific LMICs [22]. Other search terms addressed the population of interest (medical doctors), exposures of interest, and location of practice.

Both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed literature published in the last 20 years (July 1999–June 2019) were retrieved. Pubmed, Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and SCOPUS were searched. Human Resources for Health and Rural and Remote Health journals were also searched. Grey literature searches included Proquest dissertations; first 10 pages of Google Scholar for each country; hrhresourcecenter.org (category: rural/urban imbalance, deployment); WHO website; and Global Health Workforce Alliance website. We searched the eligible articles’ references to identify any additional materials.

Study selection

Included were studies investigating the following outcomes: (1) actual work, referring to current work, and; (2) preference, referring to attitude towards, intention to work and remain, in the rural and remote areas. As the 2010 WHO global policy recommendations to improve rural health worker recruitment and retention emphasize the importance of educational interventions, and to specifically explore career stage [23], the review included studies of doctors, medical students and interns. This review was restricted to university-qualified doctors or students undertaking tertiary (university-level) degree training (Table 2).

After retrieving articles and removing the duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts against inclusion/exclusion criteria. We worked independently, then in pairs, to compare assessments and reach agreement. When eligibility for inclusion differed, the team conferred to resolve difference.

Data charting and analysis methods

A spreadsheet of key factors was developed to extract relevant data. Two authors tested and refined the data extraction tool using 10 eligible studies. Information extracted covered key areas such as country, sample, rural work outcomes, and factors related to the outcomes, and organized using the categories and sub-categories of the WHO global policy recommendations [23].

To understand how eligible articles defined ‘rural’ or ‘remote’ areas, we searched for explicit and implied definitions in the text according to categories described in previous studies such as: non-metropolitan area, population density and characteristics, distance from the nearest town and environmental characteristics [24, 25].

The authors discussed, agreed on, summarized and synthesized findings and implications for future research, policy and practice. Although not the main purpose of this scoping review, an overall exploration of study quality was undertaken to identify issues in research quality and support ongoing research.

Results

Source of evidence

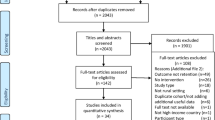

The search retrieved 3425 articles. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 71 articles were included in this review (Fig. 1). Ninety-two percent of the 71 eligible articles (see Additional file 1) were published after 2009 (Fig. 2).

Peer- and non-peer-reviewed articles on effective rural medical workforce strategies by country and year. *Countries included in multi-country studies: Bangladesh (3 articles), Cambodia (1 article), China (2 articles), India (3 articles), Nepal (2 articles), Thailand (2 articles), and Vietnam (2 articles)

Although the search was for low- and middle-income country studies, Nepal was the only low-income country (LIC; as classified in 2019) addressed in articles that met the search criteria. However, Nepal has been classified as a middle-income country (MIC) since 2020. No study from Pacific Island nations met the inclusion criteria.

Study characteristics

The majority (69%) of studies were quantitative, about one-quarter (24%) were qualitative, with the remainder (7%) policy analyses and review. More than half of studies (62%) included only tertiary-qualified doctors (at any career stage) as respondents, one-quarter (25%) of studies included only medical students and nine studies included both. Of 53 studies involving doctors (44 studies with doctors only and 9 studies with both doctors and students), half (53%) explored preference for rural work while the remaining (47%) investigated actual rural work (Table 3).

Factors associated with doctors working in rural locations

We present results of factors associated with preference or actual work in rural locations according to the WHO areas (educational, regulatory, financial incentives, and professional and personal support), and an additional category of factors related to health system contexts. Some rural work predictors identified in the MIC-based studies—such as rurally located medical school, rural clerkship and rural internship—were not identified in the studies of Nepal (the only LIC in studies that met the search criteria). Differences were due to the scope of covariates explored. Given this, and because only one LIC was included in the studies considered, we present the results of both low- and middle-income countries as a unified analysis.

There were mostly concurrences in factors associated with preference and actual rural work when studies of similar factors were explored as to their findings. Therefore, we discuss the findings in an integrated way while noting them separately in Table 4. Where relevant, any differences in preference and actual rural work outcomes are discussed.

Educational

Eighty-two percent of the articles—from 12 Asia-Pacific LMICs—were about educational factors, categorized into 2 areas: (1) student selection, and; (2) delivering medical education. For student selection, most studies demonstrated rural background was associated with both rural preference [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46, 54] and actual work [26], while several found no association with rural preference [47,48,49, 56]. Being enrolled through the 'special track', which consists of rural student recruitment, scholarships and receive a rural-oriented curriculum, were associated with actual work in rural areas [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Other student selection factors associated with rural preference were: having parents with lower educational level or wealth [38, 40, 43, 46] or with an income source from the agricultural sector [37, 44], entering medical school through a graduate track [47], and having graduated from a government-owned high school [43]; however, there was no evidence for such association with the actual work. Studies exploring the delivery of medical education found associations for both rural preference and actual work with rurally located medical schools [40, 46, 61], rural clerkship [37], and rural-oriented curricula combined with other educational strategies [27,28,29,30,31, 62,63,64,65]. Students in public medical schools were more likely to prefer rural work compared to those from private ones [43, 55]. Rural internship was cited as a negative experience leading to poorer intention to work rurally in Indonesia [80], while, when delivered as part of a rural-oriented curricula, it was associated with better rural doctor supply [64].

Regulatory

One-fifth (20%) of articles, from China, Nepal, Thailand, and Timor-Leste, examined regulatory strategies. Compulsory rural service periods, whether implemented as a stand-alone strategy [31, 81, 82], combined with scholarships only [43, 47, 66, 81], or combined with combined with scholarship and recruiting students from rural areas [27, 29,30,31, 47,48,49, 72], were associated with higher rural preference or actual work.

Financial incentives

Forty-five percent of the studies—from 12 Asia-Pacific LMICs—explored associations between rural preference or actual work and financial incentives. Despite many demonstrating that appropriate financial incentives were essential for rural doctor recruitment, it was not clear what increment of incentive was needed for optimal results. One study revealed the actual income is higher among urban than rural doctors [46]. Across studies applying discrete choice experiment (DCE) methods, the proportion of increased salary or allowances tested varied, ranging from 0 to 300%. One study demonstrated doctors and medical students were 1.1–1.3 times more likely to consider rural jobs if offered 16% higher salaries [56], while others suggested that incentives worth 45% or 50% of doctors’ salary had the highest coefficient for rural work preference [54, 74, 76]. Nonetheless, some studies found that salary increases had lower utility compared to other recruitment/retention strategies such as good working environment [37], study assistance and supportive management [75], and support for professional development [58]. Opportunities to do private work were associated with better doctor supply or preference to work in rural areas [32, 45, 50, 90].

In term of retention, good salary was the second highest reason for Filipinos doctors’ willingness to stay in rural areas after completing the rural deployment program [96]. Likewise, a 50% salary increase had the highest utility to influence rural retention among Lao doctors [76]. However, in Thailand, financial incentives were deemed less valuable for retention compared to other factors such as working environment, community and personal factors [72]. Nor did an increase in salary associate with Timorese doctors’ preferences to remain working in rural locations [58].

Personal and professional support

Over half (57%) of the articles—from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Timor-Leste and Vietnam—investigated personal and professional supports. The three most important personal and professional support strategies were working environment, living conditions and career development opportunities. Working environment included adequate facility infrastructure, equipment, drugs, and technology [34, 40, 58, 60, 75, 85, 91], sufficient number of health workers, availability of supportive mentoring or supervision, as well as availability of, and good relationships with, other health professionals [34, 46, 53, 91, 93]. Better housings [76, 92], electricity, water, and communications [52, 57, 59, 88], transportation [57, 72, 74, 76], schooling facilities [50, 53], employment opportunities for spouses [53] were the key living amenities important for doctors to work in rural locations. Clear career promotion schemes such as guarantee of permanent employment, transfer to more developed areas, or promotion opportunities were preferred to overcome rural doctor shortages [31, 54, 56, 76]. While relationship between gender and rural work preference showed mixed results (i.e., the majority found no difference, some found male prefers rural work, and others found the opposite), studies on actual rural work demonstrated that being male was associated with working in rural locations [27, 28]. Another frequently raised issues deterring doctors from rural practice was the lack of security [40, 50, 72, 73, 79, 88, 92], especially among women and in conflict-afflicted areas [57, 83].

Health systems

Some (13%) studies covered factors related to health systems issues that did not fit well into the existing WHO strategy categories [97]. These were from Bangladesh, China, Cambodia, India, Nepal, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam, and included governance, service delivery, and health financing issues impacting on rural workforce supply [32, 50, 59, 70, 73, 83].

Definitions of rural (or remote)

Definitions of rural used to describe the outcomes were grouped according to four themes identified inductively: (1) inferred with no clear description; (2) facility-related, if differentiated by health facility factors such as facility resources; (3) non-facility-related, if characterized by demographic structure, environmental characteristics, population characteristics, topography or accessibility, and; (4) combination, if combined according to points (2) and (3) above (Table 5).

Many included studies (39%) did not provide a definition of rural. Many (39%) also defined ‘rural’ based on non-facility aspects such as level of socioeconomic deprivation [32, 51, 53, 57, 62, 70, 86, 90, 91], being located outside of metropolitan areas [26,27,28,29, 48, 82], population size [42, 65], administrative unit definitions [36, 77, 84], and geographical access [50, 52, 56, 58, 83]. Some (14%) studies defined rural as working in primary care or community-level facilities or smaller hospitals [31, 47, 49, 61, 63, 64, 67, 95].

Definitions of rural varied across different studies from the same country. For example, in India, a study conducted in Odisha state considered the entire state as rural [91], while another study conducted in Andhra Pradesh [41], only classified positions in community health centers or lower-level facilities as rural. Likewise, in Indonesia, while one study defined rural districts as < 25,000 population size [42], other studies considered any areas outside of Java and Bali—the most developed regions—as rural, regardless of population size [51, 90]. Studies involving respondents from more than one country relied on respondents’ self-reporting ‘rural’ via questionnaire [33,34,35].

Rural preference and career stages

Few studies considered and the impact of career stage. Of 53 studies involving medical graduates, only 2 analyzed outcomes by length of medical career. There was no association between being in early, mid, or later career and intention to stay working rurally among doctors in rural India [91]. Among early career doctors in Thailand, rural preference was higher among a cohort of doctors finishing 2-year compulsory rural service compared to those finishing 1 year [54].

Study quality

While most of the included studies had a clear research question and coherent methods, some were of poorer quality. Only half (n = 26) of 49 quantitative studies applied multivariate analysis (Table 3) with the remainder analyzing data at a univariate level or applied descriptive statistics without adjusting for potential confounding variables. Furthermore, among studies which adjusted for confounders, several relied on subjective definitions of rural location [33,34,35, 39, 75], thereby reducing study quality. Almost all qualitative studies explained data collection methods and respondent recruitment in detail. However, less than half (n = 7) clearly described the theoretical framework used. Some qualitative studies also did not report the relationship between interviewers and respondents, qualifications of the interviewers nor whether training was conducted to ensure consistency in the quality of the interviewing, thereby weakening the credibility of reported findings [99].

Discussion

This review is the first published study to undertake a detailed synthesis of factors associated with rural medical workforce supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs. Seventy-one articles from 12 countries published between 1999 and 2019 were included. Most evidence was from India, published within the last 10 years and mainly focused on doctors in practice. Around one-third of evidence related to medical students. The spread of evidence was reasonably even across the globally recognized WHO categories of strategies for rural retention, although this review identified a new category: health systems, including government policies and political climate, found to affect the rural medical workforce.

A broad range of educational factors were associated with rural work, especially related to rural background. Both preference and actual work in rural locations were associated with having resided in rural areas during the school-age period, having graduated from a rurally located high school, or being a native of a particular area, consistent with evidence on the importance of recruiting rural-origin students to increase rural doctor supply from other regions [10, 14, 100]. Despite this widely acknowledged evidence, there remains great opportunity for selecting rural background students into medical schools in the Asia-Pacific LMICs. In some countries, such as Indonesia, where more than 50% of medical students are enrolled in private institutions [101] and most medical schools are city-based, executing such rural-focused student selection could require government to provide more financial support for rural students as rural students are less able to afford a medical education. In Thailand, only 1 out of 19 medical schools is privately owned, an easier context in which to implement rural background selection targets [102].

There was limited research isolating the effectiveness of delivering a rural-oriented curriculum, and few examples of rurally located medical schools, rural clerkships, and rural internships. The scant available evidence about rural clerkships showed a positive association with rural work preference; yet, this only applied to those with an urban background. This evidence is not currently strong enough to recommend rural clerkships, nor how to go about rural-focused education. Nonetheless, the evidence available in Asia-Pacific LMICs does suggest that combining rurally based medical education strategies with other strategies, or with other compulsory and incentivizing strategies, can improve rural supply. This is consistent with evidence from other regions that combinations of rural workforce strategies are more effective than single strategies in increasing rural doctor availability [23, 103, 104].

Financial incentives and opportunities to earn income from additional jobs, a conducive work environment, and ongoing supports for professional development were also associated with rural intention, preference, and practice. These benefits were generally coveted by doctors and compensated for the perceived disadvantages of practicing in rural areas. The availability of local amenities such as housing, road infrastructure, and schooling facilities, as well as working-environment considerations such as facility readiness, and adequacy of drugs and equipment, were also associated with doctors’ decisions about work location, supporting the widely documented evidence from around the globe [105]. These strategies—financial incentives, supportive working environments, decent local amenities, and clear career ladder as well as effective human resource management practices—are in the governments’ scope of authority and make practical sense for local governments, rural health services and communities to implement. Thus, this could be especially important because many Asia-Pacific LMICs are decentralized nations in which the management of human resources, health resources, infrastructure, and finance is devolved to local government, thereby providing local governments with a specific role in rural medical workforce management.

While good salary was of high importance for rural doctor retention in the Philippines and Lao [76, 96], studies in Thailand and Timor-Leste found no such association [58, 72]. The majority of respondents in the Thai and Timorese studies had received scholarships (88% and 93%), which may have influenced their preference regarding financial incentives. This calls for more research to explore the role of financial factors, whether given upfront as a scholarship or at the time of employment, in increasing rural doctor retention in Asia-Pacific LMICs.

Past studies indicate that initial employment experiences could play a critical role in influencing doctors’ work performance and retention [18, 106]. In South Africa, doctors who had worked in rural locations at early career stages, even as part of a compulsory assignment, were more likely to have rural work intentions [107]. However, this review identified the paucity of evidence on the association between the different length of employment and actual rural work. A better understanding on the difference of rural work across doctor’s career stages would better inform health workforce planning and decision-making, hence calls for more inquiries on this topic.

We identified that male students or doctors were more likely to prefer or actually work in rural or remote locations [27, 29, 38, 43, 47, 77] and female doctors were more affected by perceptions of lack of security than were male doctors [57, 83]. Since women dominate the doctor population in many Asia-Pacific LMICs [38, 48, 58, 76, 108], understanding the environmental and personal attributes that influence female doctors’ willingness to work rurally is crucial to inform effective policy.

The disparity between the factors related to the two outcomes—preference or actual work in rural areas—was mostly due to difference on variables studied across both outcomes. While there is some evidence that graduation from a public medical school or having lower-income parents was associated with rural work preference, the absence of evidence of these associations for actual work should encourage further investigations. This could become an invaluable policy input, especially for countries where a significant proportion of doctors attended high-fee private schools.

The review identifies some weaknesses of study methodologies. First, almost one-third of the studies did not define rural location, and, for studies that did, the definitions were non-standardized and varied significantly. Some of the definitions used may not reflect geographical and demographic aspects of rurality. This variation may not affect the utility of the study for adding to the emerging evidence about effective rural workforce strategies in Asia-Pacific LMICs; however, it does reduce the capacity to validate and generalize the findings to other contexts. The diverse rural definitions for health policy and research purposes have been previously identified and widely discussed, including in developed countries [24, 109]. The usefulness of future studies in this field could be increased by standardizing definitions of rural.

Second, the majority of included studies only asked whether respondents ever lived in rural areas, without considering any particular rural area. This did not allow any conclusions about whether exposure to any rural area, or familiarity with a specific area, has a stronger influence on doctors’ decisions about where to work. Exploring the nature of doctors’ backgrounds, and whether it is rurality in general, or attachment to a hometown, is an important topic that could provide substantial evidence for policymakers in selecting characteristics for medical students recruitment or doctor deployment.

Finally, the included studies lacked multivariate analyses that is needed to isolate the strength of association of factors related to doctors’ rural work and preference. Adjusting for potential confounders in studies on rural workforce strategies will allow policymakers to understand which of the strategies or sociodemographic characteristics need more emphasis to improve rural doctor availability.

We acknowledge that Asia-Pacific LMICs included in this review range from the world’s most populous countries with strong economic growth (e.g., China) to comparatively smaller, poorer nations with less than 2 million people (e.g., Timor-Leste). Also, no study from Pacific island nations was identified; there remains a need for more studies from these countries. The findings should be generalized with caution given the range of included material from different settings and contexts. By focusing this work on one region, and the context of LMICs being more similar than including all country types, the work substantially adds to the existing evidence for guiding rural medical workforce development in this region, including according to the WHO guidelines.

Almost all of the studies we included involved local-origin doctors, except for Timor-Leste where some doctors are from Cuba. As the poaching of medical staff between high-, middle-, and low-income countries could impact a country’s doctor supply, further research should consider supply chains, including cross-country migration and its impact on different LMICs.

Conclusions

This study provides critical new evidence, drawn from 20 years’ research, about a range of factors which can be used to target strategies to increase rural medical workforce supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs. The evidence has grown substantially, especially over the last 10 years, but remains confined to 12 Asia-Pacific LMICs. Achieving rural medical workforce growth in Asia-Pacific LMICs required multi-level approaches including selecting more medical students with a rural background, combining this with rural-focused or -located education and return-of-service scholarships, workplace and rural living support and ensuring an appropriately financed rural health system. The review identifies the need for more studies in a broader range of Asia-Pacific countries which define rural clearly, expanding on all strategy areas, use multivariate analyses, and test how various strategies relate to doctor’s career stages.

Availability of data and materials

All data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- DCE:

-

Discrete Choice Experiment

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income country

- LIC:

-

Low-income country

- MIC:

-

Middle-income country

- PRISMA-Scr:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Review

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015: 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/Res/70/1(2015).

Cometto G, Witter S. Tackling health workforce challenges to universal health coverage: setting targets and measuring progress. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:881–5.

Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G, Fogstad H, et al. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:853–63.

World Health Organization. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Human Resources for Health Observer Series No 17. Switzerland: Geneva; 2016. Report No.: 9241511400.

Cotlear D, Nagpal S, Smith O, Tandon A, Cortez R. Going universal: how 24 developing countries are implementing universal health coverage from the bottom up: The World Bank; 2015.

Anand S, Bärnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364(9445):1603–9.

Robinson JJ, Wharrad H. The relationship between attendance at birth and maternal mortality rates: an exploration of United Nations’ data sets including the ratios of physicians and nurses to population, GNP per capita and female literacy. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34(4):445–55.

Lee J, Park S, Choi K, Kwon S-m. The association between the supply of primary care physicians and population health outcomes in Korea. Fam Med. 2010;42(9):628–35.

Gulliford MC. Availability of primary care doctors and population health in England: is there an association? J Public Health. 2002;24(4):252–4.

Viscomi M, Larkins S, Sen GT. Recruitment and retention of general practitioners in rural Canada and Australia: a review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18(1):13–23.

Farmer J, Kenny A, McKinstry C, Huysmans RD. A scoping review of the association between rural medical education and rural practice location. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):27.

Parlier AB, Galvin SL, Thach S, Kruidenier D, Fagan EB. The road to rural primary care: a narrative review of factors that help develop, recruit, and retain rural primary care physicians. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):130–40.

Walters LK, McGrail MR, Carson DB, O’Sullivan BG, Russell DJ, Strasser RP, et al. Where to next for rural general practice policy and research in Australia? Med J Australia. 2017;207(2):56–8.

Laven G, Wilkinson D. Rural doctors and rural backgrounds: how strong is the evidence? A systematic review. Aust J Rural Health. 2003;11(6):277–84.

Sempowski IP. Effectiveness of financial incentives in exchange for rural and underserviced area return-of-service commitments: systematic review of the literature. Can J Rural Med. 2004;9(2):82.

Frehywot S, Mullan F, Payne PW, Ross H. Compulsory service programmes for recruiting health workers in remote and rural areas: do they work? Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(5):364–70.

Liu X, Dou L, Zhang H, Sun Y, Yuan B. Analysis of context factors in compulsory and incentive strategies for improving attraction and retention of health workers in rural and remote areas: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(61):1–8.

Purohit B, Martineau T. Initial posting—a critical stage in the employment cycle: lessons from the experience of government doctors in Gujarat, India. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):41.

The World Bank Group. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics. United States. 2019.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

The World Bank Group. World Bank Open Data United States. 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/.

World Health Organization. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: global policy recommendations: World Health Organization; 2010.

Williams AM, Cutchin MP. The rural context of health care provision. J Interprof Care. 2002;16(2):107–15.

Moran AM, Coyle J, Pope R, Boxall D, Nancarrow SA, Young J. Supervision, support and mentoring interventions for health practitioners in rural and remote contexts: an integrative review and thematic synthesis of the literature to identify mechanisms for successful outcomes. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):10.

Zimmerman M, Shakya R, Pokhrel BM, Eyal N, Rijal BP, Shrestha RN, et al. Medical students’ characteristics as predictors of career practice location: retrospective cohort study tracking graduates of Nepal’s first medical college. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2012;345:e4826.

Arora R, Chamnan P, Nitiapinyasakul A, Lertsukprasert S. Retention of doctors in rural health services in Thailand: impact of a national collaborative approach. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(4344):1–10.

Pagaiya N, Kongkam L, Sriratana S. Rural retention of doctors graduating from the rural medical education project to increase rural doctors in Thailand: a cohort study. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):10.

Techakehakij W, Arora R. Rural retention of new medical graduates from the Collaborative Project to Increase Production of Rural Doctors (CPIRD): a 12-year retrospective study. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(6):809–15.

Boonluksiri P, Tumviriyakul H, Arora R, Techakehakij W, Chamnan P, Umthong N. Community-based learning enhances doctor retention. Educ Health Change Learn Pract. 2018;31(2):114–8.

Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1(1):12.

Zhu A, Tang S, Thu NTH, Supheap L, Liu X. Analysis of strategies to attract and retain rural health workers in Cambodia, China, and Vietnam and context influencing their outcomes. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):2.

Silvestri DM, Blevins M, Afzal AR, Andrews B, Derbew M, Kaur S, et al. Medical and nursing students’ intentions to work abroad or in rural areas: a cross-sectional survey in Asia and Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(10):750–9.

Silvestri DM, Blevins M, Wallston KA, Afzal AR, Alam N, Andrews B, et al. Nonacademic attributes predict medical and nursing student intentions to emigrate or to work rurally: an eight-country survey in Asia and Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(6):1512–20.

Chuenkongkaew WL, Negandhi H, Lumbiganon P, Wang W, Mahmud K, Cuong PV. Attitude towards working in rural area and self-assessment of competencies in last year medical students: a survey of five countries in Asia. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):238.

Hou J, Xu M, Kolars JC, Dong Z, Wang W, Huang A, et al. Career preferences of graduating medical students in China: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:136.

Liu J, Zhang K, Mao Y. Attitude towards working in rural areas: a cross-sectional survey of rural-oriented tuition-waived medical students in Shaanxi, China. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):91.

Liu J, Zhu B, Mao Y. Association between rural clinical clerkship and medical students’ intentions to choose rural medical work after graduation: a cross-sectional study in western China. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195266.

Nallala S, Swain S, Das S, Kasam SK, Pati S. Why medical students do not like to join rural health service? An exploratory study in India. J Fam Commun Med. 2015;22(2):111–7.

Saini NK, Sharma R, Roy R, Verma R. What impedes working in rural areas? A study of aspiring doctors in the National Capital Region. India Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1967.

Sinha RK. Perception of young doctors towards service to rural population in Bihar. J Indian Med Assoc. 2012;110(8):530–4.

Syahmar I, Putera I, Istatik Y, Furqon MA, Findyartini A. Indonesian medical students’ preferences associated with the intention toward rural practice. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(4):3526.

Huntington I, Shrestha S, Reich NG, Hagopian A. Career intentions of medical students in the setting of Nepal’s rapidly expanding private medical education system. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(5):417–28.

Sapkota BP, Amatya A. What factors influence the choice of urban or rural location for future practice of Nepalese medical students? A cross-sectional descriptive study. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:84.

Farooq U, Ghaffar A, Narru IA, Khan D, Irshad R. Doctors perception about staying in or leaving rural health facilities in District Abbottabad. J Ayub Med College: JAMC. 2004;16(2):64–9.

Vujicic M, Shengelia B, Alfano M, Thu HB. Physician shortages in rural Vietnam: using a labor market approach to inform policy. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(7):970–7.

Qing Y, Hu G, Chen Q, Peng H, Li K, Wei J, et al. Factors that influence the choice to work in rural township health centers among 4669 clinical medical students from five medical universities in Guangxi, China. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:40.

Putthasri W, Suphanchaimat R, Topothai T, Wisaijohn T, Thammatacharee N, Tangcharoensathien V. Thailand special recruitment track of medical students: a series of annual cross-sectional surveys on the new graduates between 2010 and 2012. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:47.

Thammatacharee N, Suphanchaimat R, Wisaijohn T, Limwattananon S, Putthasri W. Attitudes toward working in rural areas of Thai medical, dental and pharmacy new graduates in 2012: a cross-sectional survey. Human Resour Health. 2013;11:53.

Darkwa EK, Newman MS, Kawkab M, Chowdhury ME. A qualitative study of factors influencing retention of doctors and nurses at rural healthcare facilities in Bangladesh. BMC Health Services Res. 2015;15(344):1–12.

Handoyo NE, Prabandari YS, Rahayu GR. Identifying motivations and personality of rural doctors: a study in Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. Educ Health (Abingdon, England). 2018;31(3):174–7.

Rajbangshi PR, Nambiar D, Choudhury N, Rao KD. Rural recruitment and retention of health workers across cadres and types of contract in north-east India: a qualitative study. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2017;6(2):51–9.

Sheikh K, Rajkumari B, Jain K, Rao K, Patanwar P, Gupta G, et al. Location and vocation: why some government doctors stay on in rural Chhattisgarh, India. Int Health. 2012;4(3):192–9.

Lagarde M, Pagaiya N, Tangcharoensathian V, Blaauw D. One size does not fit all: investigating doctors’ stated preference heterogeneity for job incentives to inform policy in Thailand. Health Econ. 2013;22(12):1452–69.

Diwan V, Minj C, Chhari N, De Costa A. Indian medical students in public and private sector medical schools: are motivations and career aspirations different?–studies from Madhya Pradesh, India. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):127.

Rao KD, Ryan M, Shroff Z, Vujicic M, Ramani S, Berman P. Rural clinician scarcity and job preferences of doctors and nurses in India: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e82984:1–9.

Sheikh K, Mondal S, Patanwar P, Rajkumari B, Sundararaman T. What rural doctors want: a qualitative study in Chhattisgarh state. Indian J Med Ethics. 2016;1(3):138–44.

Smitz MF, Witter S, Lemiere C, Eozenou PHV, Lievens T, Zaman RU, et al. Understanding health workers’ job preferences to improve rural retention in Timor-Leste: findings from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):0165940.

Goel S, Angeli F, Dhirar N, Sangwan G, Thakur K, Ruwaard D. Factors affecting medical students’ interests in working in rural areas in North India—a qualitative inquiry. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210251.

Thapa KR, Shrestha BK, Bhattarai MD. Study of working experience in remote rural areas after medical graduation. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2014;12(46):121–5.

Wang L. A comparison of metropolitan and rural medical schools in China: which schools provide rural physicians? Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10(2):94–8.

Cristobal F, Worley P. Can medical education in poor rural areas be cost-effective and sustainable: the case of the Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1835.

Halili SB Jr, Cristobal F, Woolley T, Ross SJ, Reeve C, Neusy AJ. Addressing health workforce inequities in the Mindanao regions of the Philippines: tracer study of graduates from a socially-accountable, community-engaged medical school and graduates from a conventional medical school. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):859–65.

Siega-Sur JL, Woolley T, Ross SJ, Reeve C, Neusy AJ. The impact of socially-accountable, community-engaged medical education on graduates in the Central Philippines: implications for the global rural medical workforce. Med Teach. 2017;39(10):1084–91.

Woolley T, Cristobal F, Siega-Sur JL, Ross S, Neusy A-J, Halili SB Jr, et al. Positive implications from socially accountable, community-engaged medical education across two Philippines regions. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(1):1–10.

Asante AD, Martins N, Otim ME, Dewdney J. Retaining doctors in rural Timor-Leste: a critical appraisal of the opportunities and challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(4):277–82.

Vyas R, Zachariah A, Swamidasan I, Doris P, Harris I. Evaluation of a distance learning academic support program for medical graduates during rural hospital service in India. Educ Health (Abingdon, England). 2017;30(3):240–3.

Hou X, Witter S, Zaman RU, Engelhardt K, Hafidz F, Julia F, et al. What do health workers in Timor-Leste want, know and do? Findings from a national health labour market survey. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):69.

Behera MR, Prutipinyo C, Sirichotiratana N, Viwatwongkasem C. Interventions for improved retention of skilled health workers in rural and remote areas. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2017;10(1):16–21.

Witter S, Thi Thu Ha B, Shengalia B, Vujicic M. Understanding the “four directions of travel”: qualitative research into the factors affecting recruitment and retention of doctors in rural Vietnam. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(1):20.

Shroff ZC, Murthy S, Rao KD. Attracting doctors to rural areas: a case study of the post-graduate seat reservation scheme in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Commun Med. 2013;38(1):27.

Seangrung R, Chuangchum P. Factors affecting the rural retention of medical graduates in lower northern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2017;100(6):692–701.

Butterworth K, Hayes B, Neupane B. Retention of general practitioners in rural Nepal: a qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(4):201–6.

Jaskiewicz W, Phathammavong O, Vangkonevilay P, Paphassarang C, Phachanh IT, Wurts L. Toward development of a rural retention strategy in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: understanding health worker preferences. Washington: CapacityPlus; 2012.

Efendi F, Chen C-M, Nursalam N, Andriyani NWF, Kurniati A, Nancarrow SA. How to attract health students to remote areas in Indonesia: a discrete choice experiment. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2016;31(4):430–45.nn

Keuffell E, Jaskiewicz W, Theppanya K, Tulenko K. Cost-effectiveness of rural incentive packages for graduating medical students in Lao PDR. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;6(7):383–94.nn

Liu S, Li S, Yang R, Liu T, Chen G. Job preferences for medical students in China: a discrete choice experiment. Medicine. 2018;97(38):1–9.

Raha S, Berman P, Bhatnagar A. Career preferences of medical and nursing students in Uttar Pradesh. India Health Beat. 2009;1(6):1–4.

Hayes BW, Shakya R. Career choices and what influences Nepali medical students and young doctors: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):5.n

Dasman H, Mwanri L, Martini A. Indonesian rural medical internship: the impact on health service and the future workforce. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9(7):231–6.nnn

Shankar PR. Attracting and retaining doctors in rural Nepal. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(1420):1–7.

Wiwanitkit V. Mandatory rural service for health care workers in Thailand. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(1583):1–9.

Ramani S, Rao KD, Ryan M, Vujicic M, Berman P. For more than love or money: attitudes of student and in-service health workers towards rural service in India. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):58.n

Jing L, Liu K, Zhou X, Wang L, Huang Y, Shu Z, et al. Health-personnel recruitment and retention target policy for health care providers in the rural communities: a retrospective investigation at Pudong New Area of Shanghai in China. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2019;34(1):e157–67.nn

Leonardia JA, Prytherch H, Ronquillo K, Nodora RG, Ruppel A. Assessment of factors influencing retention in the Philippine National Rural Physician Deployment Program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012a;12(1):411.n

Kadam S, Nallala S, Zodpey S, Pati S, Hussain MA, Chauhan AS, et al. A study of organizational versus individual needs related to recruitment, deployment and promotion of doctors working in the government health system in Odisha state. India Hum Resour Health. 2016;14:7.nn

Reddy PP, Anjum MS, Monica M, Rao KY, Hameed IA, Reddy JR. Compulsory 1 year rural Service-Stance of interns and postgraduates of medicine and dentistry in Hyderabad City, Telangana: a cross-sectional survey. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2017;15(4):383.nn

Rana SA, Sarfraz M, Kamran I, Jadoon H. Preferences of doctors for working in rural Islamabad Capital Territory, Pakistan: a qualitative study. J Ayub Med College: JAMC. 2016;28(3):591–6.nn

Shankar PR, Thapa TP. Student perception about working in rural Nepal after graduation: a study among first-and second-year medical students. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10(1):27.n

Meliala A, Hort K, Trisnantoro L. Addressing the unequal geographic distribution of specialist doctors in Indonesia: the role of the private sector and effectiveness of current regulations. Soc Sci Med. 2013;82:30–4.nn

Behera MR, Prutipinyo C, Sirichotiratana N, Viwatwongkasem C. Living conditions, work environment, and intention to stay among doctors working in rural areas of Odisha state, India. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2018;17(Special issue):S809.nn

Gruen R, Anwar R, Begum T, Killingsworth JR, Normand C. Dual job holding practitioners in Bangladesh: an exploration. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2002;54(2):267–79.n

Dutt RA, Shivalli S, Bhat MB, Padubidri JR. Attitudes and perceptions toward rural health care service among medical students. Med J Dr DY Patil Univ. 2014;7(6):703.n

Joarder T, Rawal LB, Ahmed SM, Uddin A, Evans TG. Retaining doctors in Rural Bangladesh: a policy analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):847–58.nn

Huang J, Shi L, Chen Y. Staff retention after the privatization of township-village health centers: a case study from the Haimen City of East China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:136.nn

Leonardia JA, Prytherch H, Ronquillo K, Nodora RG, Ruppel A. Assessment of factors influencing retention in the Philippine National Rural Physician Deployment Program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012b;12:411.nn

De Savigny D, Adam T. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva, Switzerland: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization; 2009.

Sapkota BP, Amatya A. Intended location of future career practice among graduating medical students: perspective from social cognitive career theory in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Council. 2013;11(25):229–34.n

Hannes K. Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al., editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions, Version 1: Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group; 2011.

Lehmann U, Dieleman M, Martineau T. Staffing remote rural areas in middle-and low-income countries: a literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(19):10.nnn

Anderson I, Meliala A, Marzoeki P, Pambudi E. The production, distribution, and performance of physicians, nurses, and midwives in Indonesia: an update. Washington DC, Unites States: The World Bank; 2014.

Suphanchaimat R, Wisaijohn T, Thammathacharee N, Tangcharoensathien V. Projecting Thailand physician supplies between 2012 and 2030: application of cohort approaches. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):3.

Walker JH, Dewitt D, Pallant J, Cunningham C. Rural origin plus a rural clinical school placement is a significant predictor of medical students' intentions to practice rurally: a multi-university study. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12(1908):1–9.

Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, Eley DS, Ranmuthugala G, Chater AB, Toombs MR, Darshan D, et al. Determinants of rural practice: positive interaction between rural background and rural undergraduate training. Med J Aust. 2015;202(1):41–5.

Dussault G, Franceschini MC. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4(1):12.

Briscoe F, Kellogg KC. The initial assignment effect: local employer practices and positive career outcomes for work-family program users. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76(2):291–319.

Hatcher AM, Onah M, Kornik S, Peacocke J, Reid S. Placement, support, and retention of health professionals: National, cross-sectional findings from medical and dental community service officers in South Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(14):1–13.

Hossain P, Das Gupta R, YarZar P, Salieu Jalloh M, Tasnim N, Afrin A, et al. ‘Feminization’ of physician workforce in Bangladesh, underlying factors and implications for health system: Insights from a mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210820.

Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149–55.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Penelope Presta, librarian at Monash University, for her expert advice in developing the Boolean search string. The first author also thanks The Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP scholarship) for sponsoring her doctoral study at Monash University. The authors also thank reviewers for the invaluable comments to strengthen the content of this article.

Funding

The first author received scholarships for her doctoral degree and thesis assistance fund from Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP Scholarship), Ministry of Finance, Republic Indonesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP contributed to the design, study selection, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. DR, BS and RK contributed to the study selection, data analysis and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Lists of included article.

Additional file 2.

Detailed search term for each database searching (June 1990–July 2019).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Putri, L.P., O’Sullivan, B.G., Russell, D.J. et al. Factors associated with increasing rural doctor supply in Asia-Pacific LMICs: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health 18, 93 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00533-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00533-4