Abstract

Background

A high variety of team interventions aims to improve team performance outcomes. In 2008, we conducted a systematic review to provide an overview of the scientific studies focused on these interventions. However, over the past decade, the literature on team interventions has rapidly evolved. An updated overview is therefore required, and it will focus on all possible team interventions without restrictions to a type of intervention, setting, or research design.

Objectives

To review the literature from the past decade on interventions with the goal of improving team effectiveness within healthcare organizations and identify the “evidence base” levels of the research.

Methods

Seven major databases were systematically searched for relevant articles published between 2008 and July 2018. Of the original search yield of 6025 studies, 297 studies met the inclusion criteria according to three independent authors and were subsequently included for analysis. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Scale was used to assess the level of empirical evidence.

Results

Three types of interventions were distinguished: (1) Training, which is sub-divided into training that is based on predefined principles (i.e. CRM: crew resource management and TeamSTEPPS: Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), on a specific method (i.e. simulation), or on general team training. (2) Tools covers tools that structure (i.e. SBAR: Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation, (de)briefing checklists, and rounds), facilitate (through communication technology), or trigger (through monitoring and feedback) teamwork. (3) Organizational (re)design is about (re)designing structures to stimulate team processes and team functioning. (4) A programme is a combination of the previous types. The majority of studies evaluated a training focused on the (acute) hospital care setting. Most of the evaluated interventions focused on improving non-technical skills and provided evidence of improvements.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, the number of studies on team interventions has increased exponentially. At the same time, research tends to focus on certain interventions, settings, and/or outcomes. Principle-based training (i.e. CRM and TeamSTEPPS) and simulation-based training seem to provide the greatest opportunities for reaching the improvement goals in team functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Teamwork is essential for providing care and is therefore prominent in healthcare organizations. A lack of teamwork is often identified as a primary point of vulnerability for quality and safety of care [1, 2]. Improving teamwork has therefore received top priority. There is a strong belief that effectiveness of healthcare teams can be improved by team interventions, as a wide range of studies have shown a positive effect of team interventions on performance outcomes (e.g. effectiveness, patient safety, efficiency) within diverse healthcare setting (e.g. operating theatre, intensive care unit, or nursing homes) [3,4,5,6,7].

In light of the promising effects of team interventions on team performance and care delivery, many scholars and practitioners evaluated numerous interventions. A decade ago (2008), we conducted a systematic review with the aim of providing an overview of interventions to improve team effectiveness [8]. This review showed a high variety of team interventions in terms of type of intervention (i.e. simulation training, crew resource management (CRM) training, interprofessional training, general team training, practical tools, and organizational interventions), type of teams (e.g. multi-, mono-, and interdisciplinary), type of healthcare setting (e.g. hospital, elderly care, mental health, and primary care), and quality of evidence [8]. From 2008 onward, the literature on team interventions rapidly evolved, which is evident from the number of literature reviews focusing on specific types of interventions. For example, in 2016, Hughes et al. [3] published a meta-analysis demonstrating that team training is associated with teamwork and organizational performance and has a strong potential for improving patient outcomes and patient health. In 2016, Murphy et al. [4] published a systematic review, which showed that simulation-based team training is an effective method to train a specific type of team (i.e. resuscitation teams) in the management of crisis scenarios and has the potential to improve team performance. In 2014, O’Dea et al. [9] showed with their meta-analysis that CRM training (a type of team intervention) has a strong effect on knowledge and behaviour in acute care settings (as a specific healthcare setting). In addition to the aforementioned reviews, a dozen additional literature reviews that focus on the relationship between (a specific type of) team interventions and team performance could be mentioned [7, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. In sum, the extensive empirical evidence shows that team performance can be improved through diverse team interventions.

However, each of the previously mentioned literature reviews had a narrow scope, only partly answering the much broader question of how to improve team effectiveness within healthcare organizations. Some of these reviews focus on a specific team intervention, while others on a specific area of health care. For example, Tan et al. [7] presented an overview on team simulation in the operating theatre and O’Dea et al. [9] focused on CRM intervention in acute care. Other reviews only include studies with a certain design. For instance, Fung et al. [13] included only randomized controlled trials, quasi-randomized controlled trials, controlled before-after studies, or interrupted time series. Since the publication of our systematic review in 2010 [8], there has been no updated overview of the wide range of team interventions without restrictions regarding the type of team intervention, healthcare setting, type of team, or research design. Based on the number and variety of literature reviews conducted in recent years, we can state that knowledge on how to improve team effectiveness (and related outcomes) has progressed quickly, but at the same time is quite scattered. An updated systematic review covering the past decade is therefore relevant.

The purpose of this study is to answer two research questions: (1) What types of interventions to improve team effectiveness (or related outcomes) in health care have been researched empirically, for which setting, and for which outcomes (in the last decade)? (2) To what extent are these findings evidence based?

Methodology

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a research librarian from a medical library who specializes in designing systematic reviews. The search combined keywords from four areas: (1) team (e.g. team, teamwork), (2) health care (e.g. health care, nurse, medical, doctor, paramedic), (3) interventions (e.g. programme, intervention, training, tool, checklist, team building), (4) improving team functioning (e.g. outcome, performance, function) OR a specific performance outcome (e.g. communication, competence, skill, efficiency, productivity, effectiveness, innovation, satisfaction, well-being, knowledge, attitude). This is similar to the search terms in the initial systematic review [8]. The search was conducted in the following databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL EBSCO, and Google Scholar. The EMBASE version of the detailed strategy was used as the basis for the other search strategies and is provided as additional material (see Additional file 1). The searches were restricted to articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2008 and July 2018. This resulted in 5763 articles. In addition, 262 articles were identified through the systematic reviews published in the last decade [3, 4, 7, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In total, 6025 articles were screened.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review aims to capture the full spectrum of studies that empirically demonstrate how healthcare organizations could improve team effectiveness. Therefore, the following studies were excluded:

-

1.

Studies outside the healthcare setting were excluded. Dental care was excluded. We did not restrict the review to any other healthcare setting.

-

2.

Studies without (unique) empirical data were excluded, such as literature reviews and editorial letters. Studies were included regardless of their study design as long as empirical data was presented. Book chapters were excluded, as they are not published in peer-reviewed journals.

-

3.

Studies were excluded that present empirical data but without an outcome measure related to team functioning and team effectiveness. For example, a study that evaluates a team training without showing its effect on team functioning (or care provision) was excluded because it does not provide evidence on how this team training affects team functioning.

-

4.

Studies were excluded that did not include a team intervention or that included an intervention that did not primarily focus on improving team processes, which is likely to enhance team effectiveness (or other related outcomes). An example of an excluded study is a training that aims to improve technical skills such as reanimation skills within a team and sequentially improves communication (without aiming to improve communication). It is not realistic that healthcare organizations will implement this training in order to improve team communication. Interventions in order to improve collaboration between teams from different organizations were also eliminated.

-

5.

Studies with students as the main target group. An example of an excluded study is a curriculum on teamwork for medical students as a part of the medical training, which has an effect on collaboration. This is outside the scope of our review, which focuses on how healthcare organizations are able to improve team effectiveness.

In addition, how teams were defined was not a selection criterion. Given the variety of teams in the healthcare field, we found it acceptable if studies claim that the setting consists of healthcare teams.

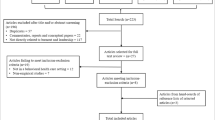

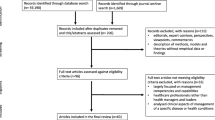

Selection process

Figure 1 summarizes the search and screening process according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) format. A four-stage process was followed to select potential articles. We started with 6025 articles. First, each title and abstract was subjected to elimination based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two reviewers reviewed the title/abstracts independently. Disagreement between the reviewers was settled by a third reviewer. In case of doubt, it was referred to the next stage. The first stage reduced the number of hits to 639. Second, the full text articles were assessed for eligibility according to the same set of elimination criteria. After the full texts were read by two reviewers, 343 articles were excluded. In total, 297 articles were included in this review. Fourth, the included articles are summarized in Table 1. Each article is described using the following structure:

-

Type of intervention

-

Setting: the setting where the intervention is introduced is described in accordance with the article, without further categorization

-

Outcomes: the effect of the intervention

-

Quality of evidence: the level of empirical evidence is based in the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) scale. GRADE distinguishes four levels of quality of evidence

-

A.

High: future research is highly unlikely to change the confidence in the estimated effect of the intervention.

-

B.

Moderate: future research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimated effect of the intervention and may change it.

-

C.

Low: future research is very likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimated effect of the intervention and is likely to change it.

-

D.

Very low: any estimated effect of the intervention is very uncertain.

-

A.

Studies can also be upgraded or downgraded based on additional criteria. For example, a study is downgraded by one category in the event there are important inconsistencies. Detailed information is provided as additional material (see Additional file 2).

Organization of results

The categorization of our final set of 297 articles is the result of three iterations. First, 50 summarized articles were categorized using the initial categorization: team training (subcategories: CRM-based training, simulation training, interprofessional training, and team training), tools, and organizational intervention [8]. Based on this first iteration, the main three categories (i.e. training, tools, and organizational interventions) remained unchanged but the subcategorization was further developed. Training, related to the subcategory “CRM-based training”, “TeamSTEPPS” was added as a subcategory. The other subcategories (i.e. simulation training, interprofessional training, and team training) remained the same. Tools, the first draft of subcategories, entailed Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR), checklists, (de)briefing, and task tools. Two subcategories of organizational intervention (i.e. programme and (re)design) were created, which was also in line with the content of this category in the original literature review. Second, 50 additional articles were categorized to test and refine the subcategories. Based on this second iteration, the subcategories were clustered, restructured and renamed, but the initial three main categorizations remained unaffected. The five subcategories of training were clustered into principle-based training, method-based training, and general team training. The tools subcategories were clustered into structuring, facilitating, and triggering tools, which also required two new subcategories: rounds and technology. Third, the remaining 197 articles were categorized to test the refined categorization. In addition, the latter categorization was peer reviewed. The third iteration resulted in three alterations. First, we created two main categories based on the two subcategories “organizational (re)design” and “programme” (of the third main categorization). Consequently, we rephrased “programme-based training” into “principle-based training”. Second, the subcategories “educational intervention” and “general team training” were merged into “general team training”. Consequently, we rephrased “simulation training” into “simulation-based training”. Third, we repositioned the subcategories “(de)briefing” and “rounds” as structuring tools instead of facilitating tools. Consequently, we merged the subcategories “(de)briefing” and “checklists” into “(de)briefing checklists”. Thereby, the subcategory “technology” became redundant.

Results

Four main categories are distinguished: training, tools, organizational (re)design, and programme. The first category, training, is divided in training that is based on specific principles and a combination of methods (i.e. CRM and Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS)), a specific training method (i.e. training with simulation as a core element), or general team training, which refers to broad team training in which a clear underlying principle or specific method is not specified. The second category, tools, are instruments that are introduced to improve teamwork by structuring (i.e. SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation), (de)briefing checklists, and rounds), facilitating (through communication technology), or triggering (through monitoring and feedback) team interaction. Structuring tools partly standardize the process of team interaction. Facilitating tools provide better opportunities for team interaction. Triggering tools provide information to incentivize team interaction. The third category, organizational (re)design, refers to (re)designing structures (through implementing pathways, redesigning schedules, introducing or redesigning roles and responsibilities) that will lead to improved team processes and functioning. The fourth category, a programme, refers to a combination of the previous types of interventions (i.e. training, tools, and/or redesign). Table 2 presents the (sub)categorization, number of studies, and a short description of each (sub)category.

Overall findings

Type of intervention

The majority of studies evaluated a training. Simulation-based training is the most frequently researched type of team training.

Setting

Most of the articles researched an acute hospital setting. Examples of acute hospital settings are the emergency department, operating theatre, intensive care, acute elderly care, and surgical unit. Less attention was paid to primary care settings, nursing homes, elderly care, or long-term care in general.

Outcome

Interventions focused especially on improving non-technical skills, which refer to cognitive and social skills such as team working, communication, situational awareness, leadership, decision making, and task management [21]. Most studies relied on subjective measures to indicate an improvement in team functioning, with only a few studies (also) using objective measures. The Safety Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ) and the Non-Technical Skills (NOTECHS) tool are frequently used instruments to measure perceived team functioning.

Quality of evidence

A bulk of the studies had a low level of evidence. A pre- and post-study is a frequently used design. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have used an action research approach, which often creates more insight into the processes of implementing and tailoring an intervention than the more frequently used designs (e.g. Random Control Trial and pre-post surveys). However, these valuable insights are not fully appreciated within the GRADE scale.

The findings per category will be discussed in greater detail in the following paragraphs.

Training

CRM and TeamSTEPPS are well-known principle-based trainings that aim to improve teamwork and patient safety in a hospital setting. Both types of training are based on similar principles. CRM is often referred to as a training intervention that mainly covers non-technical skills such as situational awareness, decision making, teamwork, leadership, coping with stress, and managing fatigue. A typical CRM training consists of a combination of information-based methods (e.g. lectures), demonstration-based methods (e.g. videos), and practice-based methods (e.g. simulation, role playing) [9]. However, CRM has a management concept at its core that aims to maximize the use of all available resources (i.e. equipment, time, procedures, and people) [324]. CRM aims to prevent and manage errors through avoiding errors, trapping errors before they are committed, and mitigating the consequences of errors that are not trapped [325]. Approximately a third of CRM-based trainings include the development, redesign or implementation of learned CRM techniques/tools (e.g. briefing, debriefing, checklists) and could therefore also be categorized in this review under programme [39, 40, 42, 51, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62].

The studies show a high variety in the content of CRM training and in the results measured. The majority of the studies claim an improvement in a number of non-technical skills that were measured, but some also show that not all non-technical skills measured were improved [43, 47, 66]. Moreover, the skills that did or did not improve differed between the studies. A few studies also looked at outcome measures (e.g. clinical outcomes, error rates) and showed mixed results [49, 52, 53]. Notable is the increasing attention toward nursing CRM, which is an adaptation of CRM to nursing units [66, 67]. Most studies delivered a low to moderate quality level of evidence. Although most studies measured the effect of CRM over a longer period of time, most time periods were limited to one or two evaluations within a year. Savage et al. [58] and Ricci et al. [56] note the importance of using a longer time period.

As a result of experienced shortcomings of CRM, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) has evolved (since 2006). TeamSTEPPS is a systematic approach designed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense (DoD) to enhance teamwork skills that are essential to the delivery of quality and safe care. Some refer to TeamSTEPPS as “CRM and more”. TeamSTEPPS provides an approach on preparing, implementing, and sustaining team training. It is provided as a flexible training kit and facilitates in developing a tailored plan. It promotes competencies, strategies, and the use of standardized tools on five domains of teamwork: team structure, leadership, communication, situational monitoring, and mutual support. In addition, TeamSTEPPS focuses on change management, coaching, measurement, and implementation. Notable is that even though the TeamSTEPSS training is most likely to differ across settings as it needs to be tailored to the situational context, articles provide limited information on the training content. All studies report improvements in some non-technical skills (e.g. teamwork, communication, safety culture). Combining non-technical skills with outcome measures (e.g. errors, throughput time) seemed more common in this category. Half of the studies delivered a moderate to high quality of evidence.

Simulation-based training uses a specific method as its core, namely, simulation, which refers to “a technique to replace or amplify real-patient experiences with guided experiences, artificially contrived, that evokes or replicates substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner” [326]. The simulated scenarios that are used can have different forms (e.g. in situ simulation, in centre simulation, human actors, mannequin patients) and are built around a clinical scenario (e.g. resuscitation, bypass, trauma patients) aiming to improve technical and/or non-technical skills (e.g. interprofessional collaboration, communication). We only identified studies in a hospital setting, which were mostly focussed on an emergency setting. All studies reported improvements in some non-technical skills (e.g. teamwork behaviour, communication, shared mental model, clarity in roles and responsibilities). In addition, some studies report non-significant changes in non-technical skills [98, 137, 140, 155]. Some studies also looked at technical skills (e.g. time spend) and presented mixed results [63, 112, 152, 159]. Sixty-nine studies focused on simulation-based training, of which 16 studies delivered a moderate to high quality of evidence.

General team training does not focus on one specific training principle or method. It often contains multiple educational forms such as didactic lectures, interactive sessions, and online modules. General team training focuses on a broad target group and entails for example team building training, coaching training, and communication skills training. Due to the broad scope of this category, high variation in outcomes is noted, although many positive outcomes were found. Most studies have a low to very low level of evidence.

Tools

Tools are instruments that could be implemented relatively independently in order to structure, facilitate or trigger teamwork.

Structuring tools

Teamwork can be structured by using the structured communication technique SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation), (de)briefing checklists, and rounds.

SBAR is often studied in combination with strategies to facilitate implementation, such as didactic sessions, training, information material, and modifying SBAR material (e.g. cards) [202, 204, 206,207,208, 211]. In addition, this subcategory entails communication techniques similar or based on SBAR [203, 205, 209, 210, 212]. One study focused on nursing homes, while the remaining studies were performed in a hospital setting. Most studies found improvements in communication; however, a few found mixed results [208, 209]. Only (very) low-level evidence studies were identified.

Briefings and debriefings create an opportunity for professionals to systematically communicate and discuss (potential) issues before or after delivering care to a patient, based on a structured format of elements/topics or a checklist with open and/or closed-end questions. Studies on (de)briefing checklists often evaluate the implementation of the World Health Organization surgical safety checklist (SSC), a modified SSC, SSC-based checklist, or a safety checklist in addition to the SSC. The SSC consists of a set of questions with structured answers that should be asked and answered before induction of anaesthesia, before skin incision, and before the patient leaves the operating theatre. In addition, several studies presented checklists aiming to better manage critical events [221, 223, 233]. Only one study on SSC was conducted outside the surgery department/operating theatre (i.e. cardiac catheterization laboratory [222]). However, similar tools can also be effective in settings outside the hospital, as shown by two studies that focused on the long-term care setting [249, 260]. Overall, included studies show that (de)briefing checklists help improve a variety of non-technical skills (e.g. communication, teamwork, safety climate) and objective outcome measures (e.g. reduced complications, errors, unexpected delays, morbidity). At the same time, some studies show mixed results or are more critical of its (sustainable) effect [215, 222, 231, 242]. Whyte et al. [262] pointed out the complexity of this intervention by presenting five paradoxical findings: team briefings could mask knowledge gaps, disrupt positive communication, reinforce professional divisions, create tension, and perpetuate a problematic culture. The quality of evidence varied from high to very low (e.g. Whyte et al. [262]), and approximately one third presented a high or moderate quality of evidence. Debriefings can also be used as part of a training, aiming to provide feedback on trained skills. Consequently, some articles focused on the most suitable type of debriefing in a training setting (e.g. video-based, self-led, instructor-led) [245, 246, 253, 263] or debriefing as reflection method to enhance performance [258, 261].

Rounds can be described as structured interdisciplinary meetings around a patient. Rounds were solely researched in hospital settings. Five studies found improvements in non-technical skills, one study in technical skills, and one study reported outcomes but found no improvement. Three studies presented a moderate level of evidence, and the others presented a (very) low level.

Facilitating tools

Teamwork can be facilitated through technology. Technology, such as telecommunication, facilitates teamwork as it creates the opportunity to involve and interact with professionals from a distance [271,272,273]. Technology also creates opportunities to exchange information through information platforms [276, 277]. Most studies found positive results for teamwork. Studies were performed in a hospital setting and presented a level of evidence varying from moderate to very low.

Triggering tools

Teamwork could be triggered by tools that monitor and visualize information, such as (score) cards and dashboards [278, 279, 281, 283, 284]. The gathered information does not echo team performance but creates incentives for reflecting on and improving teamwork. Team processes (e.g. trust, reflection) are also triggered by sharing experiences, such as clinical cases and stories, thoughts of the day [280, 282]. All seven studies showed improvements in non-technical skills and had a very low level of evidence.

Organizational (re)design

In contrast with the previous two categories, organizational (re)design is about changing organizational structures. Interventions can be focused on several elements within a healthcare organization, such as the payment system [292] and the physical environment [299], but are most frequently aimed at standardization of processes in pathways [286, 288] and changing roles and responsibilities [287, 289, 298], sometimes by forming dedicated teams or localizing professionals to a certain unit or patient [290, 291, 295, 300]. Most studies found some improvements of non-technical skills; however, a few found mixed results. Only four studies had a moderate level of evidence, and the others had a (very) low level.

Programme

A programme most frequently consists of a so-called Human Resource Management bundle that combines learning and educational sessions (e.g. simulation training, congress, colloquium), often multiple tools (e.g. rounds, SBAR), and/or structural intervention (e.g. meetings, standardization). Moreover, a programme frequently takes the organizational context into account: developing an improvement plan and making choices tailored to the local situation. A specific example is the “Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program” (CUSP) that combines training (i.e. science of safety training educational curriculum, identify safety hazards, learn from defects) with the implementation of tools (e.g. team-based goal sheet), and structural intervention (i.e. senior executive partnership, including nurses on rounds, forming an interdisciplinary team) [309, 319, 322]. Another example is the medical team training (MTT) programme that consists of three stages: (1) preparation and follow-up, (2) learning session, (3) implementation and follow-up. MTT combines training, implementation of tools (briefings, debriefing, and other projects), and follow-up coaching [5, 304, 305, 316]. MMT programmes are typically based on CRM principles, but they distinguish themselves from the first category by extending their programme with other types of interventions. Most studies focus on the hospital setting, with the exception of the few studies performed in the primary care, mental health care, and healthcare system. Due to the wide range of programmes, the outcomes were diverse but mostly positive. The quality of evidence varied from high to very low.

Conclusion and discussion

This systematic literature review shows that studies on improving team functioning in health care focus on four types of interventions: training, tools, organizational (re)design, and programmes. Training is divided into principle-based training (subcategories: CRM-based training and TeamSTEPPS), method-based training (simulation-based training), and general team training. Tools are instruments that could be implemented relatively independently in order to structure (subcategories: SBAR, (de)briefing checklists, and rounds), facilitate (through communication technology), or trigger teamwork (through information provision and monitoring). Organizational (re)design focuses on intervening in structures, which will consequently improve team functioning. Programmes refer to a combination of different types of interventions.

Training is the most frequently researched intervention and is most likely to be effective. The majority of the studies focused on the (acute) hospital care setting, looking at several interventions (e.g. CRM, TeamSTEPPS, simulation, SBAR, (de)briefing checklist). Long-term care settings received less attention. Most of the evaluated interventions focused on improving non-technical skills and provided evidence of improvements; objective outcome measures also received attention (e.g. errors, throughput time). Looking at the quantity and quality of evidence, principle-based training (i.e. CRM and TeamSTEPPS), simulation-based training, and (de)briefing checklist seem to provide the biggest chance of reaching the desired improvements in team functioning. In addition, programmes, in which different interventions are combined, show promising results for enhancing team functioning. The category programmes not only exemplify this trend, but are also seen in principle-based training.

Because this review is an update of our review conducted in 2008 (and published in 2010) [8], the question of how the literature evolved in the last decade arises. This current review shows that in the past 10 years significantly more research has focused on team interventions in comparison to the previous period. However, the main focus is on a few specific interventions (i.e. CRM, simulation, (de)briefing checklist). Nevertheless, an increasing number of studies are evaluating programmes in which several types of interventions are combined.

-

Training: There has been a sharp increase in research studying team training (from 32 to 173 studies). However, the majority of these studies still look at similar instruments, namely, CRM-based and simulation-based training. TeamSTEPPS is a standardized training that has received considerable attention in the past decade. There is now a relatively strong evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions, but mostly for the (acute) hospital setting.

-

Tools: There is also a substantial increase (from 8 to 84 studies) in studies on tools. Again, many of these studies were in the same setting (acute hospital care) and focused on two specific tools, namely, the SBAR and (de)briefing checklist. Although the level of evidence for the whole category tools is ambiguous, there is relatively strong evidence for the effectiveness of the (de)briefing checklist. Studies on tools that facilitate teamwork ascended the past decade. There is limited evidence that suggests these may enhance teamwork. The dominant setting was again hospital care, though triggering tools were also studied in other settings such as acute elderly care and clinical primary care. Moreover, most studies had a (very) low quality of evidence, which is an improvement compared to the previous review that solely presented (very) low level of evidence.

-

Organizational (re)design: More attention is paid to organizational (re)design (from 8 to 16 studies). Although the number of studies on this subject has increased, there still remains unclarity about its effects because of the variation in interventions and the mixed nature of the results.

-

Programmes: There seems to be new focus on a programmatic approach in which training, tools, and/or organizational (re)design are combined, often focused around the topic patient safety. The previous review identified only one such study; this research found 24 studies, not including the CRM studies for which some also use a more programmatic approach. There seems to be stronger evidence that this approach of combining interventions may be effective in improving teamwork.

Limitations

The main limitation of this review is that we cannot claim that we have found every single study per subcategory. This would have required per subcategory an additional systematic review or an umbrella review, using additional keywords. As we identified a variety of literature reviews, future research should focus on umbrella reviews in addition to new systematic literature reviews. Note that we did find more studies per subcategory, but they did not meet our inclusion criteria. For example, we excluded multiple studies evaluating surgical checklists that did not measure its effect on team functioning but only on reported errors or morbidity. Although this review presents all relevant categories to improve team functioning in healthcare organizations, those categories are limited to team literature and are not based on related research fields such as integrated care and network medicine. Another limitation is that we excluded grey literature by only focusing on articles written in English that present empirical data and were published in peer-reviewed journals. Consequently, we might have excluded studies that present negative or non-significant effects of team interventions, and such an exclusion is also known as publication bias. In addition, the combination of the publication bias and the exclusion of grey literature has probably resulted in a main focus on standardized interventions and a limited range of alternative approaches, which does not necessarily reflect practice.

Implication for future research

This review shows the major increase in the last decade in the number of studies on how to improve team functioning in healthcare organizations. At the same time, it shows that this research tends to focus around certain interventions, settings, and outcomes. This helped to provide more evidence but also left four major gaps in the current literature. First, less evidence is available about interventions to improve team functioning outside the hospital setting (e.g. primary care, youth care, mental health care, care for disabled people). With the worldwide trend to provide more care at home, this is an important gap. Thereby, team characteristics across healthcare settings vary significantly, which challenges the generalizability [327]. Second, little is known about the long-term effects of the implemented interventions. We call for more research that monitors the effects over a longer period of time and provides insights into factors that influence their sustainability. Third, studies often provide too little information about the context. To truly understand why a team intervention affects performance and to be able to replicate the effect (by researchers and practitioners), detailed information is required related to the implementation process of the intervention and the context. Fourth, the total picture of relevant outcomes is missing. We encourage research that includes less frequently used outcomes such as well-being of professionals and focuses on identifying possible deadly combinations between outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- CRM:

-

Crew resource management

- CUSP:

-

Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program

- DoD:

-

Department of Defense

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development, and Evaluation

- MTT:

-

Medical team training

- NOTECHS:

-

Non-Technical Skills

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SAQ:

-

Safety Attitude Questionnaire

- SBAR:

-

Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation

- SSC:

-

Surgical safety checklist

- TeamSTEPPS:

-

Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety

References

Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To err is human: building a safer health system: National Academies Press; 2000.

Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:143–51.

Hughes AM, Gregory ME, Joseph DL, Sonesh SC, Marlow SL, Lacerenza CN, et al. Saving lives: a meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101:1266–304.

Murphy M, Curtis K, McCloughen A. What is the impact of multidisciplinary team simulation training on team performance and efficiency of patient care? An integrative review. Australasian Emerg Nurs J. 2016;19(1):44–53.

Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, Carney BT, West P, Berger DH, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304:1693–700.

Salas E, Klein C, King H, Salisbury M, Augenstein JS, Birnbach DJ, et al. Debriefing medical teams: 12 evidence-based best practices and tips. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:518–27.

Tan SB, Pena G, Altree M, Maddern GJ. Multidisciplinary team simulation for the operating theatre: a review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84(7-8):515–22.

Buljac-Samardzic M, Dekker-van Doorn CM, Van Wijngaarden JDH, Van Wijk KP. Interventions to improve team effectiveness: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2010;94(3):183–95.

O’Dea A, O’Connor P, Keogh I. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of crew resource management training in acute care domains. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:699–708.

Maynard MT, Marshall D, Dean MD. Crew resource management and teamwork training in health care: a review of the literature and recommendations for how to leverage such interventions to enhance patient safety. Adv Health Care Manag. 2012;13:59–91.

Verbeek-van Noord I, de Bruijne MC, Zwijnenberg NC, Jansma EP, van Dyck C, Wagner C. Does classroom-based crew resource management training improve patient safety culture? A systematic review. SAGE open medicine. 2014;2:2050312114529561.

Boet S, Bould MD, Fung L, Qosa H, Perrier L, Tavares W, et al. Transfer of learning and patient outcome in simulated crisis resource management: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie. 2014;61(6):571–82.

Fung L, Boet S, Bould MD, Qosa H, Perrier L, Tricco A, et al. Impact of crisis resource management simulation-based training for interprofessional and interdisciplinary teams: a systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(5):433–44.

Doumouras AG, Keshet I, Nathens AB, Ahmed N, Hicks CM. A crisis of faith? A review of simulation in teaching team-based, crisis management skills to surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(3):274–81.

Weaver SJ, Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Lazzara EH, Lyons R, Salas E, et al. Does teamwork improve performance in the operating room? A multilevel evaluation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:133–42.

McCulloch P, Rathbone J, Catchpole K. Interventions to improve teamwork and communications among healthcare staff. Br J Surg. 2011;98(4):469–79.

Carne B, Kennedy M, Gray T. Review article: crisis resource management in emergency medicine. EMA Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24:7–13.

Russ S, Rout S, Sevdalis N, Moorthy K, Darzi A, Vincent C. Do safety checklists improve teamwork and communication in the operating room? A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2013;258:856–71.

Sacks GD, Shannon EM, Dawes AJ, Rollo JC, Nguyen DK, Russell MM, et al. Teamwork, communication and safety climate: a systematic review of interventions to improve surgical culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:458–67.

Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA. Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):359–72.

Shields A, Flin R. Paramedics' non-technical skills: a literature review. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(5):350–4.

McEwan D, Ruissen GR, Eys MA, Zumbo BD, Beauchamp MR. The effectiveness of teamwork training on teamwork behaviors and team performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventions. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0169604.

Borchard A, Schwappach DLB, Barbir A, Bezzola P. A systematic review of the effectiveness, compliance, and critical factors for implementation of safety checklists in surgery. Ann Surg. 2012 Dec;256:925–33.

Robertson JM, Dias RD, Yule S, Smink DS. Operating room team training with simulation: a systematic review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27(5):475–80.

Cunningham U, Ward M, De Brún A, McAuliffe E. Team interventions in acute hospital contexts: a systematic search of the literature using realist synthesis. BMC health services research. 2018;18(1):536.

Cheng A, Eppich W, Grant V, Sherbino J, Zendejas B, Cook DA. Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2014;48(7):657–66.

Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081–9.

Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):3.

Allan CK, Thiagarajan RR, Beke D, Imprescia A, Kappus LJ, Garden A, et al. Simulation-based training delivered directly to the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit engenders preparedness, comfort, and decreased anxiety among multidisciplinary resuscitation teams. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:646–52.

Ballangrud R, Hall-Lord M, Persenius M, Hedelin B. Intensive care nurses' perceptions of simulation-based team training for building patient safety in intensive care: a descriptive qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30:179–87.

Bank I, Snell L, Bhanji F. Pediatric crisis resource management training improves emergency medicine trainees' perceived ability to manage emergencies and ability to identify teamwork errors. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:879–83.

Budin WC, Gennaro S, O'Connor C, Contratti F. Sustainability of improvements in perinatal teamwork and safety climate. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29:363–70.

Carbo AR, Tess AV, Roy C, Weingart SN. Developing a high-performance team training framework for internal medicine residents: the ABC'S of teamwork. J Patient Saf. 2011;7:72–6.

Catchpole KR, Dale TJ, Hirst DG, Smith JP, Giddings TA. A multicenter trial of aviation-style training for surgical teams. J Patient Saf. 2010;6:180–6.

Clay-Williams R, McIntosh CA, Kerridge R, Braithwaite J. Classroom and simulation team training: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:314–21.

Cooper JB, Blum RH, Carroll JS, Dershwitz M, Feinstein DM, Gaba DM, et al. Differences in safety climate among hospital anesthesia departments and the effect of a realistic simulation-based training program. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:574–84.

France DJ, Leming-Lee S, Jackson T, Feistritzer NR, Higgins MS. An observational analysis of surgical team compliance with perioperative safety practices after crew resource management training. Am J Surg. 2008;195:546–53.

Gardner R, Walzer TB, Simon R, Raemer DB. Obstetric simulation as a risk control strategy: course design and evaluation. Simul Healthc. 2008;3:119–27.

Gore DC, Powell JM, Baer JG, Sexton KH. Crew resource management improved perception of patient safety in the operating room. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(1):60–3.

Haerkens MHTM, Kox M, Noe PM, van dH, Pickkers P. Crew resource management in the trauma room: a prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2017.

Haller G, Garnerin P, Morales MA, Pfister R, Berner M, Irion O, et al. Effect of crew resource management training in a multidisciplinary obstetrical setting. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:254–63.

Hefner JL, Hilligoss B, Knupp A, Bournique J, Sullivan J, Adkins E, et al. Cultural transformation after implementation of Crew Resource Management: is it really possible? Am J Med Qual. 2017;32:384–90.

Hicks CM, Kiss A, Bandiera GW, Denny CJ. Crisis Resources for Emergency Workers (CREW II): results of a pilot study and simulation-based crisis resource management course for emergency medicine residents. Can J Emerg Med. 2012;14:354–62.

Hughes KM, Benenson RS, Krichten AE, Clancy KD, Ryan JP, Hammond C. A crew resource management program tailored to trauma resuscitation improves team behavior and communication. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:545–51.

de Korne DF, van Wijngaarden JDH, van Dyck C, Hiddema UF, Klazinga NS. Evaluation of aviation-based safety team training in a hospital in The Netherlands. J.Health Organ.Manag. 2014;28:731–53.

Kuy S, Romero RAL. Improving staff perception of a safety climate with crew resource management training. J Surg Res. 2017;213:177–83.

LaPoint JL. The effects of aviation error management training on perioperative safety attitudes. Intern J Business and Soc Sci. 2012;3:2.

Mahramus TL, Penoyer DA, Waterval EM, Sole ML, Bowe EM. Two Hours of Teamwork Training Improves Teamwork in Simulated Cardiopulmonary Arrest Events. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016;30:284–91.

McCulloch P, Mishra A, Handa A, Dale T, Hirst G, Catchpole K. The effects of aviation-style non-technical skills training on technical performance and outcome in the operating theatre. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:109–15.

Mehta N, Boynton C, Boss L, Morris H, Tatla T. Multidisciplinary difficult airway simulation training: two year evaluation and validation of a novel training approach at a District General Hospital based in the UK. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2013;270:211–7.

Morgan L, Pickering SP, Hadi M, Robertson E, New S, Griffin D, et al. A combined teamwork training and work standardisation intervention in operating theatres: controlled interrupted time series study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:111–9.

Morgan L, Hadi M, Pickering S, Robertson E, Griffin D, Collins G, et al. The effect of teamwork training on team performance and clinical outcome in elective orthopaedic surgery: a controlled interrupted time series study. BMJ Open. 2015;5.

Müller MP, Hänsel M, Fichtner A, Hardt F, Weber S, Kirschbaum C, et al. Excellence in performance and stress reduction during two different full scale simulator training courses: a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2009;80(8):919–24.

Parsons JR, Crichlow A, Ponnuru S, Shewokis PA, Goswami V, Griswold S. Filling the gap: simulation-based crisis resource management training for emergency medicine residents. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:205–10.

Phipps MG, Lindquist DG, McConaughey E, O'Brien JA, Raker CA, Paglia MJ. Outcomes from a labor and delivery team training program with simulation component. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:3–9.

Ricci MA, Brumsted JR. Crew resource management: using aviation techniques to improve operating room safety. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2012;83(4):441–4.

Robertson B, Schumacher L, Gosman G, Kanfer R, Kelley M, DeVita M. Simulation-based crisis team training for multidisciplinary obstetric providers. Simul Healthc. 2009;4:77–83.

Savage C, Andrew Gaffney F, Hussainalkhateeb L, Ackheim PO, Henricson G, Antoniadou I, et al. Safer paediatric surgical teams: a 5-year evaluation of crew resource management implementation and outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29:853–60.

Sax HC, Browne P, Mayewski RJ. Can aviation-based team training elicit sustainable behavioral change?: archopht.jamanetwork.com; 2009.

Shea-Lewis A. Teamwork: crew resource management in a community hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31:14–8.

Schwartz ME, Welsh DE, Paull DE, Knowles RS, DeLeeuw LD, Hemphill RR, et al. The effects of crew resource management on teamwork and safety climate at Veterans Health Administration facilities. 2017.

Sculli GL, Fore AM, West P, Neily J, Mills PD, Paull DE. Nursing crew resource management a follow-up report from the Veterans Health Administration. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:122–6.

Steinemann S, Berg B, Skinner A, Ditulio A, Anzelon K, Terada K, et al. In situ, multidisciplinary, simulation-based teamwork training improves early trauma care. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:472–7.

Stevens LM, Cooper JB, Raemer DB, Schneider RC, Frankel AS, Berry WR, et al. Educational program in crisis management for cardiac surgery teams including high realism simulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:17–24.

Suva D, Haller G, Lübbeke A, Hoffmeyer P. Differential impact of a crew resource management program according to professional specialty. Am J Med Qual 2012;27:313-320.

Tschannen D, McClish D, Aebersold M, Rohde JM. Targeted communication intervention using nursing crew resource management principles. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(1):7–11.

West P, Sculli G, Fore A, Okam N, Dunlap C, Neily J, et al. Improving patient safety and optimizing nursing teamwork using crew resource management techniques. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42:15–20.

Ziesmann MT, Widder S, Park J, Kortbeek JB, Brindley P, Hameed M, et al. S.T.A.R.T.T.: development of a national, multidisciplinary trauma crisis resource management curriculum-results from the pilot course. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:753–8.

Forse RA, Bramble JD, McQuillan R. Team training can improve operating room performance. Surgery (USA). 2011;150:771–8.

Bridges R, Sherwood G, Durham C. Measuring the influence of a mutual support educational intervention within a nursing team. Int J Nurs Sci. 2014;1:15–22.

Brodsky D, Gupta M, Quinn M, Smallcomb J, Mao W, Koyama N, et al. Building collaborative teams in neonatal intensive care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:374–82.

Bui AH, Guerrier S, Feldman DL, Kischak P, Mudiraj S, Somerville D, et al. Is video observation as effective as live observation in improving teamwork in the operating room? Surgery. 2018;163:1191–6.

Capella J, Smith S, Philp A, Putnam T, Gilbert C, Fry W, et al. Teamwork training improves the clinical care of trauma patients. J Surg Educ. 2010;67:439–43.

Castner J, Foltz-Ramos K, Schwartz DG, Ceravolo DJ. A leadership challenge: staff nurse perceptions after an organizational TeamSTEPPS initiative. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42:467–72.

Deering S, Johnston LC, Colacchio K. Multidisciplinary teamwork and communication training. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:89–96.

Figueroa MI, Sepanski R, Goldberg SP, Shah S. Improving teamwork, confidence, and collaboration among members of a pediatric cardiovascular intensive care unit multidisciplinary team using simulation-based team training. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:612–9.

Gaston T, Short N, Ralyea C, Casterline G. Promoting patient safety results of a TeamSTEPPS (R) initiative. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46:201–7.

Gupta RT, Sexton JB, Milne J, Frush DP. Practice and quality improvement: successful implementation of TeamSTEPPS tools into an academic interventional ultrasound practice. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:105–10.

Harvey EM, Echols SR, Clark R, Lee E. Comparison of two TeamSTEPPS (R) training methods on nurse failure-to-rescue performance. Clin.Simul.Nurs. 2014;10:E57–64.

Jones KJ, Skinner AM, High R. A theory-driven, longitudinal evaluation of the impact of team training on safety culture in 24 hospitals. BMJ quality and safety. 2013.

Jones F, Podila P, Powers C. Creating a culture of safety in the emergency department: the value of teamwork training. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:194–200.

Lee SH, Khanuja HS, Blanding RJ, Sedgwick J, Pressimone K, Ficke JR, et al. Sustaining teamwork behaviors through reinforcement of TeamSTEPPS principles. J Patient Saf. 2017.

Lisbon D, Allin D, Cleek C, Roop L, Brimacombe M, Downes C, et al. Improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after implementation of TeamSTEPPS training in an academic emergency department: A Pilot Report. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31:86–90.

Mahoney JS, Ellis TE, Garland G, Palyo N, Greene PK. Supporting a psychiatric hospital culture of safety. J Am Psychiatr Nurs Assoc. 2012;18:299–306.

Mayer CM, Cluff L, Lin WT, Willis TS, Stafford RE, Williams C, et al. Evaluating efforts to optimize TeamSTEPPS implementation in surgical and pediatric intensive care units. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:365–74.

Rice Y, DeLetter M, Fryman L, Parrish E, Velotta C, Talley C. Implementation and evaluation of a team simulation training program. J Trauma Nurs. 2016;23:298–303.

Riley W, Davis S, Miller K, Hansen H, Sainfort F, Sweet R. Didactic and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:357–64.

Sawyer T, Laubach VA, Hudak J, Yamamura K, Pocrnich A. Improvements in teamwork during neonatal resuscitation after interprofessional TeamSTEPPS training. Neonatal Netw. 2013;32:26–33.

Sonesh SC, Gregory ME, Hughes AM, Feitosa J, Benishek LE, Verhoeven D, et al. Team training in obstetrics: a multi-level evaluation. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:250–61.

Spiva L, Robertson B, Delk ML, Patrick S, Kimrey MM, Green B, et al. Effectiveness of team training on fall prevention. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29:164–73.

Stead K, Kumar S, Schultz TJ, Tiver S, Pirone CJ, Adams RJ, et al. Teams communicating through STEPPS. Med J Aust. 2009;190:S128–32.

Thomas L, Galla C. Building a culture of safety through team training and engagement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:425–34.

Treadwell J, Binder B, Symes L, Krepper R. Delivering team training to medical home staff to impact perceptions of collaboration. Professional case management. 2015;20(2):81–8.

Vertino KA. Evaluation of a TeamSTEPPS© initiative on staff attitudes toward teamwork. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44:97–102.

Wong AH, Gang M, Szyld D, Mahoney H. Making an "attitude adjustment": using a simulation-enhanced interprofessional education strategy to improve attitudes toward teamwork and communication. Simul.healthc. 2016;11:117–25.

AbdelFattah KR, Spalding MC, Leshikar D, Gardner AK. Team-based simulations for new surgeons: does early and often make a difference? Surgery. 2018;163:912–5.

Amiel I, Simon D, Merin O, Ziv A. Mobile in situ simulation as a tool for evaluation and improvement of trauma treatment in the emergency department. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:121–8.

Arora S, Cox C, Davies S, Kassab E, Mahoney P, Sharma E, et al. Towards the next frontier for simulation-based training: full-hospital simulation across the entire patient pathway. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):252–8.

Arora S, Hull L, Fitzpatrick M, Sevdalis N, Birnbach DJ. Crisis management on surgical wards: a simulation-based approach to enhancing technical, teamwork, and patient interaction skills. Ann Surg. 2015;261:888–93.

Artyomenko VV, Nosenko VM. Anaesthesiologists' simulation training during emergencies in obstetrics. Romanian J Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;24:37–40.

Auerbach M, Roney L, Aysseh A, Gawel M, Koziel J, Barre K, et al. In situ pediatric trauma simulation: assessing the impact and feasibility of an interdisciplinary pediatric in situ trauma care quality improvement simulation program. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:884–91.

Bender J, Kennally K, Shields R, Overly F. Does simulation booster impact retention of resuscitation procedural skills and teamwork. J Perinatol. 2014;34:664–8.

Bittencourt T, Kerrey BT, Taylor RG, FitzGerald M, Geis GL. Teamwork skills in actual, in situ, and in-center pediatric emergencies performance levels across settings and perceptions of comparative educational impact. Simul.Healthc. 2015;10:76–84.

Bruppacher HR, Alam SK, Leblanc VR, Latter D, Naik VN, Savoldelli GL, et al. Simulation-based training improves physicians performance in patient care in high-stakes clinical setting of cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:985–92.

Bursiek AA, Hopkins MR, Breitkopf DM, Grubbs PL, Joswiak ME, Klipfel JM, et al. Use of high-fidelity simulation to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration and reduce patient falls. J Patient Saf. 2017;07.

Burton KS, Pendergrass TL, Byczkowski TL, Taylor RG, Moyer MR, Falcone RA, et al. Impact of simulation-based extracorporeal membrane oxygenation training in the simulation laboratory and clinical environment. Simul Healthc. 2011;6:284–91.

Chung SP, Cho J, Park YS, Kang HG, Kim CW, Song KJ, et al. Effects of script-based role play in cardiopulmonary resuscitation team training. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2011;28(8):690–4.

Cooper S, Cant R, Porter J, Missen K, Sparkes L, McConnell-Henry T, et al. Managing patient deterioration: assessing teamwork and individual performance. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:377–81.

Ciporen J, Gillham H, Noles M, Dillman D, Baskerville M, Haley C, et al. Crisis management simulation: establishing a dual neurosurgery and anesthesia training experience. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2018;30:65–70.

Ellis D, Crofts JF, Hunt LP, Read M, Fox R, James M. Hospital, simulation center, and teamwork training for eclampsia management: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:723–31.

Fernando A, Attoe C, Jaye P, Cross S, Pathan J, Wessely S. Improving interprofessional approaches to physical and psychiatric comorbidities through simulation. Clin.Simul.Nurs. 2017;13:186–93.

Fouilloux V, Gsell T, Lebel S, Kreitmann B, Berdah S. Assessment of team training in management of adverse acute events occurring during cardiopulmonary bypass procedure: a pilot study based on an animal simulation model (Fouilloux, Team training in cardiac surgery). Perfusion. 2014;29:44–52.

Fransen AF, Ven VD, AER Mén, De Wit-Zuurendonk LD, Houterman S, Mol BW, et al. Effect of obstetric team training on team performance and medical technical skills: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:1387–93.

Freeth D, Ayida G, Berridge EJ, Mackintosh N, Norris B, Sadler C, et al. Multidisciplinary obstetric simulated emergency scenarios (MOSES): promoting patient safety in obstetrics with teamwork-focused interprofessional simulations. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:98–104.

Frengley RW, Weller JM, Torrie J, Dzendrowskyj P, Yee B, Paul AM, et al. The effect of a simulation-based training intervention on the performance of established critical care unit teams. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2605–11.

George KL, Quatrara B. Interprofessional simulations promote knowledge retention and enhance perceptions of teamwork skills in a surgical-trauma-burn intensive care unit setting. Dccn. 2018;37:144–55.

Gettman MT, Pereira CW, Lipsky K, Wilson T, Arnold JJ, Leibovich BC, et al. Use of high fidelity operating room simulation to assess and teach communication, teamwork and laparoscopic skills: initial experience. J Urol. 2009;181:1289–96.

Gilfoyle E, Koot DA, Annear JC, Bhanji F, Cheng A, Duff JP, et al. Improved clinical performance and teamwork of pediatric interprofessional resuscitation teams with a simulation-based educational intervention. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e62–9.

Gum L, Greenhill J, Dix K. Clinical simulation in maternity (CSiM): interprofessional learning through simulation team training. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e19.

Hamilton NA, Kieninger AN, Woodhouse J, Freeman BD, Murray D, Klingensmith ME. Video review using a reliable evaluation metric improves team function in high-fidelity simulated trauma resuscitation. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:428–31.

Hoang TN, Kang J, Siriratsivawong K, LaPorta A, Heck A, Ferraro J, et al. Hyper-realistic, team-centered fleet surgical team training provides sustained improvements in performance. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:668–74.

James TA, Page JS, Sprague J. Promoting interprofessional collaboration in oncology through a teamwork skills simulation programme. J Interprof Care. 2016;7:1–3.

Kalisch BJ, Gosselin K, Choi SH. A comparison of patient care units with high versus low levels of missed nursing care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37:320–8.

Khobrani A, Patel NH, George RL, McNinch NL, Ahmed RA. Pediatric trauma boot camp: a simulation curriculum and pilot study. Emerg.Med.Int. 2018.

Kilday D, Spiva L, Barnett J, Parker C, Hart P. The effectiveness of combined training modalities on neonatal rapid response teams. Clin.Simul.Nurs. 2013;9:E249–56.

Kirschbaum KA, Rask JP, Brennan M, Phelan S, Fortner SA. Improved climate, culture, and communication through multidisciplinary training and instruction. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:200.e1–7.

Koutantji M, McCulloch P, Undre S, Gautama S, Cunniffe S, Sevdalis N, et al. Is team training in briefings for surgical teams feasible in simulation? Cognition, Technology & Work. 2008;10(4):275–85.

Kumar A, Sturrock S, Wallace EM, Nestel D, Lucey D, Stoyles S, et al. Evaluation of learning from Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training and its impact on patient outcomes in Australia using Kirkpatrick's framework: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2018;17(8):e017451.

Larkin AC, Cahan MA, Whalen G, Hatem D, Starr S, Haley HL, et al. Human emotion and response in surgery (HEARS): a simulation-based curriculum for communication skills, systems-based practice, and professionalism in surgical residency training. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:285–92.

Lavelle M, Abthorpe J, Simpson T, Reedy G, Little F, Banerjee A. MBRRACE in simulation: an evaluation of a multi-disciplinary simulation training for medical emergencies in obstetrics (MEmO). J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018:1–8.

Lavelle M, Attoe C, Tritschler C, Cross S. Managing medical emergencies in mental health settings using an interprofessional in-situ simulation training programme: a mixed methods evaluation study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;59:103–9.

Lee JY, Mucksavage P, Canales C, McDougall EM, Lin S. High fidelity simulation based team training in urology: a preliminary interdisciplinary study of technical and nontechnical skills in laparoscopic complications management. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1385–91.

Lorello GR, Hicks CM, Ahmed SA, Unger Z, Chandra D, Hayter MA. Mental practice: a simple tool to enhance team-based trauma resuscitation. Can J Emerg Med. 2016;18:136–42.

Mager DR, Lange JW, Greiner PA, Saracino KH. Using simulation pedagogy to enhance teamwork and communication in the care of older adults: the ELDER project. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2012;43:363–9.

Maxson PM, Dozois EJ, Holubar SD, Wrobleski DM, Dube JAO, Klipfel JM, et al. Enhancing nurse and physician collaboration in clinical decision making through high-fidelity interdisciplinary simulation training. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:31–6.

McLaughlin T, Hennecke P, Garraway NR, Evans DC, Hameed M, Simons RK, et al. A predeployment trauma team training course creates confidence in teamwork and clinical skills: a post-Afghanistan deployment validation study of Canadian Forces healthcare personnel. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2011;71(5):487–93.

Meurling L, Hedman L. Felländer-Tsai L, Wallin CJ. Leaders' and followers' individual experiences during the early phase of simulation-based team training: an exploratory study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:459–67.

Miller D, Crandall C, Washington Iii C, McLaughlin S. Improving teamwork and communication in trauma care through in situ simulations. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:608–12.

van der Nelson SD, Bennett J, Godfrey M, Spray L, Draycott T, et al. Multiprofessional team simulation training, based on an obstetric model, can improve teamwork in other areas of health care. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29:78–82.

Nicksa GA, Anderson C, Fidler R, Stewart L. Innovative approach using interprofessional simulation to educate surgical residents in technical and nontechnical skills in high-risk clinical scenarios. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:201–7.

Niell BL, Kattapuram T, Halpern EF, Salazar GM, Penzias A, Bonk SS, et al. Prospective analysis of an interprofessional team training program using high-fidelity simulation of contrast reactions. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:W670–6.

Oseni Z, Than HH, Kolakowska E, Chalmers L, Hanboonkunupakarn B, McGready R. Video-based feedback as a method for training rural healthcare workers to manage medical emergencies: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:149.

Paige JT, Kozmenko V, Yang T, Gururaja RP, Hilton CW, Cohn I Jr, et al. Attitudinal changes resulting from repetitive training of operating room personnel using high-fidelity simulation at the point of care. Am Surg. 2009;75:584–90.

Paltved C, Bjerregaard AT, Krogh K, Pedersen JJ, Musaeus P. Designing in situ simulation in the emergency department: evaluating safety attitudes amongst physicians and nurses. Adv Simul (Lond). 2017;2:4.

Pascual JL, Holena DN, Vella MA, Palmieri J, Sicoutris C, Selvan B, et al. Short simulation training improves objective skills in established advanced practitioners managing emergencies on the ward and surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2011;71:330–8.

Patterson MD, Geis GL, Falcone RA. In situ simulation: detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(6):468–77.

Patterson MD, Geis GL, LeMaster T, Wears RL. Impact of multidisciplinary simulation-based training on patient safety in a paediatric emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:383–93.

Pennington KM, Dong Y, Coville HH, Wang B, Gajic O, Kelm DJ. Evaluation of TEAM dynamics before and after remote simulation training utilizing CERTAIN platform. Med.educ.online. 2018;23:1485431.

Rao R, Dumon KR, Neylan CJ, Morris JB, Riddle EW, Sensenig R, et al. Can simulated team tasks be used to improve nontechnical skills in the operating room? J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e42–7.

Reynolds A, Ayres-De-Campos D, Lobo M. Self-perceived impact of simulation-based training on the management of real-life obstetrical emergencies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;159:72–6.

Roberts NK, Williams RG, Schwind CJ, Sutyak JA, McDowell C, Griffen D, et al. The impact of brief team communication, leadership and team behavior training on ad hoc team performance in trauma care settings. Am J Surg. 2014;207:170–8.

Rubio-Gurung S, Putet G, Touzet S, Gauthier-Moulinier H, Jordan I, Beissel A, et al. In situ simulation training for neonatal resuscitation: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e790–7.

Sandahl C, Gustafsson H, Wallin CJ, Meurling L, Øvretveit J, Brommels M, et al. Simulation team training for improved teamwork in an intensive care unit. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2013;26:174–88.

Shoushtarian M, Barnett M, McMahon F, Ferris J. Impact of introducing Practical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training (PROMPT) into maternity units in Victoria, Australia. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:1710–8.

Siassakos D, Fox R, Hunt L, Farey J, Laxton C, Winter C, et al. Attitudes toward safety and teamwork in a maternity unit with embedded team training. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:132–7.

Siassakos D, Hasafa Z, Sibanda T, Fox R, Donald F, Winter C, et al. Retrospective cohort study of diagnosis-delivery interval with umbilical cord prolapse: the effect of team training. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116:1089–96.

Silberman NJ, Mintz SB, Zych N, Bloch N, Tal ER, Rios L. Simulation training facilitates physical therapists' self-efficacy in the intensive care unit. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2018;9:47–59.

Stewart-Parker E, Galloway R, Vig S. S-TEAMS: a truly multiprofessional course focusing on nontechnical skills to improve patient safety in the operating theater. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:137–44.

Stocker M, Allen M, Pool N, De Costa K, Combes J, West N, et al. Impact of an embedded simulation team training programme in a paediatric intensive care unit: a prospective, single-centre, longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:99–104.

Sudikoff SN, Overly FL, Shapiro MJ. High-fidelity medical simulation as a technique to improve pediatric residents' emergency airway management and teamwork: a pilot study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:651–6.

Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, Lasky RE, Crandell S, Taggarte WR. Team training in the Neonatal Resuscitation Program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics. 2010;125:539–46.

Weller J, Civil I, Torrie J, Cumin D, Garden A, Corter A, et al. Can team training make surgery safer? Lessons for national implementation of a simulation-based programme. New Zealand Med J. 2016;129:9–17.

Willaert W, Aggarwal R, Bicknell C, Hamady M, Darzi A, Vermassen F, et al. Patient-specific simulation in carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1700–5.

Yang LY, Yang YY, Huang CC, Liang JF, Lee FY, Cheng HM, et al. Simulation-based inter-professional education to improve attitudes towards collaborative practice: a prospective comparative pilot study in a Chinese medical centre. BMJ Open. 2017;8(7):e015105.

Acai A, McQueen SA, Fahim C, Wagner N, McKinnon V, Boston J, et al. “It's not the form; it's the process”: a phenomenological study on the use of creative professional development workshops to improve teamwork and communication skills. Med.Humanit. 2016;42:173–80.

Agarwal G, Idenouye P, Hilts L, Risdon C. Development of a program for improving interprofessional relationships through intentional conversations in primary care. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:432–5.

Amaya-Anas A, Idarraga D, Giraldo V, Gomez LM. Effectiveness of a program for improving teamwork in operating rooms. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:68–75.

Barrett A, Piatek C, Korber S, Padula C. Lessons learned from a lateral violence and team-building intervention. Nurs Adm Q. 2009;33:342–51.

Bleakley A, Allard J, Hobbs A. Towards culture change in the operating theatre: embedding a complex educational intervention to improve teamwork climate. Med Teach. 2012;34:e635–40.

Blegen MA, Sehgal NL, Alldredge BK, Gearhart S, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Improving safety culture on adult medical units through multidisciplinary teamwork and communication interventions: the TOPS Project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:346–50.

Brajtman S, Hall P, Barnes P. Enhancing interprofessional education in end-of-life care: an interdisciplinary exploration of death and dying in literature. J Palliat Care. 2009;25:125–31.

Brajtman S, Wright D, Hall P, Bush SH, Bekele E. Toward better care of delirious patients at the end of life: a pilot study of an interprofessional educational intervention. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:422–5.

Brandler TC, Laser J, Williamson AK, Louie J, Esposito MJ. Team-based learning in a pathology residency training program. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142:23–8.

Chan BC, Perkins D, Wan Q, Zwar N, Daniel C, Crookes P, et al. Finding common ground? Evaluating an intervention to improve teamwork among primary health-care professionals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:519–24.

Christiansen MF, Wallace A, Newton JM, Caldwell N, Mann-Salinas E. Improving teamwork and resiliency of burn center nurses through a standardized staff development program. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:e708–14.

Chiocchio F, Rabbat F, Lebel P. Multi-level efficacy evidence of a combined interprofessional collaboration and project management training program for healthcare project teams. Proj.Manag.J. 2015;46:20–34.

Cohen EV, Hagestuen R, González-Ramos G, Cohen HW, Bassich C, Book E, et al. Interprofessional education increases knowledge, promotes team building, and changes practice in the care of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;22:21-27.

Cole DC, Giordano CR, Vasilopoulos T, Fahy BG. Resident physicians improve nontechnical skills when on operating room management and leadership rotation. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:300–7.

Eklof M, Ahlborg GA. Improving communication among healthcare workers: a controlled study. J.Workplace Learn. 2016;28:81–96.

Ellis M, Kell B. Development, delivery and evaluation of a team building project. LEADERSHIP HEALTH SERV (1751-1879) 2014;27:51-66.

Ericson-Lidman E, Strandberg G. Care providers learning to deal with troubled conscience through participatory action research. Action Research. 2013;11:386–402.

Fallowfield L, Langridge C, Jenkins V. Communication skills training for breast cancer teams talking about trials. Breast. 2014;23:193–7.

Fernandez R, Pearce M, Grand JA, Rench TA, Jones KA, Chao GT, et al. A randomized comparison study to evaluate the effectiveness of a computer-based teamwork training intervention on medical teamwork and patient care performance. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:S125.

Gibon AS, Merckaert I, Lienard A, Libert Y, Delvaux N, Marchal S, et al. Is it possible to improve radiotherapy team members' communication skills? A randomized study assessing the efficacy of a 38-h communication skills training program. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:170–7.

Gillespie BM, Harbeck E, Kang E, Steel C, Fairweather N, Panuwatwanich K, et al. Effects of a brief team training program on surgical teams' nontechnical skills: an interrupted time-series study. Journal of Patient Safety. 2017.

Gillespie BM, Steel C, Kang E, Harbeck E, Nikolic K, Fairweather N, et al. Evaluation of a brief team training intervention in surgery: a mixed-methods study. AORN J. 2017;106:513–22.

Halverson AL, Andersson JL, Anderson K, Lombardo J, Park CS, Rademaker AW, et al. Surgical team training: the Northwestern Memorial Hospital experience. Arch Surg. 2009;144:107–12.

Howe JL, Penrod JD, Gottesman E, Bean A, Kramer BJ. The rural interdisciplinary team training program: a workforce development workshop to increase geriatrics knowledge and skills for rural providers. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018 Mar;27:1–13.

Kelm DJ, Ridgeway JL, Gas BL, Mohan M, Cook DA, Nelson DR, et al. Mindfulness meditation and interprofessional cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a mixed-methods pilot study. Teach Learn Med. 2018 May;18:1–11.

Khanna N, Shaya FT, Gaitonde P, Abiamiri A, Steffen B, Sharp D. Evaluation of PCMH model adoption on teamwork and impact on patient access and safety. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8:77–82.

Korner M, Luzay L, Plewnia A, Becker S, Rundel M, Zimmermann L, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled study to evaluate a team coaching concept for improving teamwork and patient-centeredness in rehabilitation teams. PLoS ONE. 2017;12.

Lavoie-Tremblay M, O'Connor P, Biron A, Lavigne GL. Fréchette J, Briand A. The effects of the transforming care at the bedside program on perceived team effectiveness and patient outcomes. Health Care Manag. 2017;36:10–20.

Lee P, Allen K, Daly M. A 'Communication and patient safety' training programme for all healthcare staff: can it make a difference? BMJ Qual.Saf. 2012 Jan;21:84–8.

Ling L, Gomersall CD, Samy W, Joynt GM, Leung CC, Wong WT, et al. The Effect of a freely available flipped classroom course on health care worker patient safety culture: a prospective controlled study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e180.

Lundén M, Lundgren SM, Morrison-Helme M, Lepp M. Professional development for radiographers and post graduate nurses in radiological interventions: building teamwork and collaboration through drama. Radiography. 2017;23:330–6.

Mager DR, Lange J. Teambuilding across healthcare professions: the ELDER project. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27:141–3.

Magrane D, Khan O, Pigeon Y, Leadley J, Grigsby RK. Learning about teams by participating in teams. Acad Med. 2010;85:1303–11.

Nancarrow SA, Smith T, Ariss S, Enderby PM. Qualitative evaluation of the implementation of the Interdisciplinary Management Tool: a reflective tool to enhance interdisciplinary teamwork using Structured, Facilitated Action Research for Implementation. Health Soc Care Community. 2015;23:437–48.

Prewett MS, Brannick MT, Peckler B. Training teamwork in medicine: an active approach using role play and feedback. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;43:316–28.

Stephens T, Hunningher A, Mills H, Freeth D. An interprofessional training course in crises and human factors for perioperative teams. J.Interprofessional Care. 2016;30:685–8.