Abstract

Background

Advanced models including time-lapse imaging and artificial intelligence technologies have been used to predict blastocyst formation. However, the conventional morphological evaluation of embryos is still widely used. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the predictive power of conventional morphological evaluation regarding blastocyst formation.

Methods

Retrospective evaluation of data from 15,613 patients receiving blastocyst culture from January 2013 through December 2020 in our institution were reviewed. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to establish the morphology-based model. To estimate whether including more features regarding patient characteristics and cycle parameters improve the predicting power, we also establish models including 27 more features with either LASSO regression or XGbosst. The predicted number of blastocyst were associated with the observed number of the blastocyst and were used to predict the blastocyst transfer cancellation either in fresh or frozen cycles.

Results

Based on early cleavage and routine observed morphological parameters (cell number, fragmentation, and symmetry), the GEE model predicted blastocyst formation with an AUC of 0.779(95%CI: 0.77–0.787) and an accuracy of 74.7%(95%CI: 73.9%-75.5%) in the validation set. LASSO regression model and XGboost model based on the combination of cycle characteristics and embryo morphology yielded similar predicting power with AUCs of 0.78(95%CI: 0.771–0.789) and 0.754(95%CI: 0.745–0.763), respectively. For per-cycle blastocyst yield, the predicted number of blastocysts using morphological parameters alone strongly correlated with observed blastocyst number (r = 0.897, P < 0.0001) and predicted blastocyst transfer cancel with an AUC of 0.926((95%CI: 0.911–0.94).

Conclusion

The data suggested that routine morphology observation remained a feasible tool to support an informed decision regarding the day of transfer. However, models based on the combination of cycle characteristics and embryo morphology do not increase the predicting power significantly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in embryo culture systems promote the currency of moving toward blastocyst transfer [1]. Extending the duration of embryo culture to the blastocyst stage may have several advantages, including a higher implantation rate over cleavage transfer and the potential to reduce the number of embryos transferred. Theoretically, blastocyst culture may help select the most viable embryo for transfer. However, low blastocyst formation rate may lead to an increase risk of transfer cancellation [1]. While the good-prognosis patients may benefit from blastocyst transfer, the patients with unfavorable characteristics, such as poor response or advanced age, may suffer an increased incidence of canceled transfers [2, 3]. Canceled transfer may add to the burden of infertile couples, both emotionally and economically. Therefore, predicting the possibility of blastocyst formation might be the key to giving a meaningful informed consent before providing blastocyst culture, especially for patients with few embryos available on day 3.

In efforts to facilitate the clinical decision-making before blastocyst culture and transfer, several models were developed to predict the blastocyst transfer cancellation or blastocyst formation for individual patients [4, 5], which demonstrated that the greatest predict value may lie in the number and quality of day 3 embryos. In recent years,‘OMICS’ technologies [6], and algorithms created through the use of time-lapse microscopy [7] were used to predict the destiny of day 3 embryos during in vitro culture. While ‘OMICS’ technologies, such as proteomics and metabolomics for non-invasive embryo developmental capacity assessment, are yet to be recommended for routine use [1], time-lapse microscopy has been introduced as a routine clinical practice and showed a capacity to predict the blastocyst formation with AUCs ranging from 0.6–0.8 across different studies [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Unfortunately, novel technologies inevitably require additional cost or equipment and the expense of technologies may limit their widespread use.

Although afflicted by subjectivity and limited efficacy, conventional embryo morphological assessment at fixed time point remained the standard of practice [20] in the era of ‘OMICS’ and time-lapse microscope. Since the early days of blastocyst culture, associations between day 3 morphology and blastocyst formation have been demonstrated. However, poor-looking day 3 embryos rejected by conventional embryo morphological assessment may also have a chance to develop into blastocysts and it is believed that the associations between morphology and blastocyst formation do not necessarily correlate with blastocyst viability. Nevertheless, data from studies predicting blastocyst formation using conventional morphological assessment and time-lapse microscopy in the same population [16, 18], showed that AUCs of conventional embryo morphological assessment for blastocyst formation were close to that of time-lapse microscopy. Especially, in the work of Petersen et al., which compared six time-lapse algorithms in the same study, only two algorithm surpassed an algorithm based on conventional Alpha/ESHRE consensus assessment in terms of predictive power [16]. Therefore, these data may suggest that the routine practice of laboratory remained a useful tool to predict blastocyst culture cancellation and provide meaningful clinical consultation, without additional cost or equipment. However, most of the previous studies focused on the assessment and selection of individual embryo and the performance of morphological based algorithms in predicting canceled blastocyst transfer cycle is less known. According to the previous studies [4, 5], there are still several other clinical and cycle based factors associated with blastocyst development besides the number and quality of day 3 embryos, and the morphology/ morphokinetic of day 3 embryos is also confounded by the cycle based factors they derived from [21]. The purpose of the study was to estimate the value of conventional embryo assessment until day 3 as tool to predict cycle based blastocyst-transfer cancellation rates.

In addition, contribution of cycle based factors to the predictive power was also evaluated by comparing the algorithms involving cycle based factors with those without.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

A retrospective analysis was performed on patients who underwent IVF/ICSI treatment in the Center for Reproduction Medicine of the affiliated Chenggong Hospital of Xiamen University, China, between January 2013 to December 2020. Institutional Review Board approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Medical College Xiamen University. Informed consent was not necessary, because the research was based on non-identifiable records as approved by the ethics committee.

The data from cycles in the period between January 2013 to December 2019 were obtained to create models to predict blastulation. The data from cycles in the period between January 2020 to December 2020 were obtained to validate the model. The inclusion criteria were the cycles accepted blastocyst culture and all parameters recorded precisely.

All patients were treated with conventional agonist or antagonist stimulation protocol in our center as previously described [22]. The initial and ongoing dosage was determined by patients’ age, antral follicle count (AFC), BMI, and ovarian response. When at least one follicle reached a mean diameter of 18 mm, An intramuscular injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (4000–6000 IU, hCG; Livzen, China) or a subcutaneous injection of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin (250 μg, Ovidrel, Merck-Serono, Switzerland) was administrated for final triggering. Oocytes were retrieved under transvaginal ultrasound guidance 34–36 h after hCG injection.

Embryo culture and assessment

Conventional IVF and ICSI protocol in our center were carried out [23]. After insemination, oocytes were cultured individually in preequilibrated Cleavage Medium (Cook) under mineral oil in traditional incubators (C200, Labotect) at 37℃, 6% CO2 and 5% O2 in a humidified atmosphere. In day3 morning, the culture media was switched to Blastocyst Medium (Cook) in the same culture condition. The culture system kept unchanged in the period of study.

Embryos were observed at the time according to Istanbul consensus [24]. Fertilization, early cleavage, the number and symmetry of blastomeres, fragmentation level on day 3 and blastocyst formation on day 5 and 6 were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The blastocyst formation as the endpoint was defined as formation of viable blastocysts for either transfer for cryopreservation. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to establish the morphology-based model. The features included in the model were early cleavage (with or without), the cell number on day 3 (2–3 cells, 4–6 cells, 7 cells, 8 cells, 9–11 cells, > 12 cells, and compact), fragmentation rate (continuous), and asymmetry (with or without). The grouping strategy for cell number on day 3 was based on the distribution of blastocyst formation (Figure S1).

To estimate whether including features regarding patient characteristics and cycle parameters improve the predicting power, we also establish models including 27 more features to establish additional models. The additional features were: female age, male age, GnRH analogues, insemination protocol, TESA/PESA, maternal height, maternal weight, maternal BMI, maternal basal FSH, maternal basal LH, maternal basal PRL, maternal basal E2, maternal basal T, basal AFC, gonadotropin dose, gonadotropin duration, HMG dose, HMG duration, starting dose, FSH on the day of stimulation, LH on the day of stimulation, E2 on the day of stimulation, E2 on the day of triggering, LH on the day of triggering, P on the day of triggering, oocyte yield, and maturation rate of oocytes in the cycle.

Two strategies were used to incorporate the features in the predicting models. First, a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) model [25] was used for feature selection, and the resulting features along with morphological parameters were used to predict the blastocyst formation (LASSO model). Second, an Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGboost) algorithm [26] was used to establish gradient boosting trees with the features (XGboost model).

Predicting power of the models was quantified with the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with area under the curve (AUC). A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for the AUC. A cutoff point for prediction was determined according to the maximum informedness (sensitivity + specificity-1) and the predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the given point were also calculated accordingly.

Because cancellation of blastocyst transfer was cycle based, we also attempted to evaluate the clinical usefulness of the blastocyst formation prediction of individual embryos in a given cycle. Models were used to calculate the predicted number of blastocysts in cycles. The predicted number of blastocyst correlated to the observed number of the blastocyst with Spearman‘s rank correlation and mean absolute difference between the prediction and observation was calculated.

The cumulative probability of predicted blastocyst formation of individual embryos in a cycle was used to predict whether the cycle have blastocyst for transfer. The cumulative probability was defined as follows. Cumulative probability = 1-∏(1-individulal embryo blastocyst formation rate).

The predicting power was compared to a cycle-based model based on XGboost with 29 features. The features included the aforementioned patient characteristics and cycle parameters, as well as the number of good quality embryos and whether all cleavages were subjected to blastocyst culture in cycles.

Calibration curves were used to report clinical agreement between model predictions and observed outcomes in the large. A calibration curve was plotted by comparing the relationship between model values and observed rates, grouped by deciles of model values. When the predicted number of blastocysts were used for prediction, a logistical transfer was used in order to obtain a linear relationship.

The calibration slope was used to evaluate the spread of the estimated rates with a target value of 1. A slope < 1 suggests that the prediction was too extreme and a slope > 1 suggests the opposite. The calibration intercept with a target value of 0, was an assessment of calibration-in-the-large. The negative intercept suggested overestimation, whereas positive intercept suggest underestimation.

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.1.2, R Core Team 2021).

Result

Training data included 13,674 cycles. The median of maternal age is 30[28-33]. 3010(23.1%) cycles accepted ICSI and 10,038(76.9%) accepted IVF treatment. A total of 96,378 embryos were cultured for blastulation. Early cleavage occurred in 42,669(44.3%) embryos. In the end, 55,323(57.4%) embryos developed to blastocysts. Another 1956 cycles were included to validate the model. The median of maternal age is 31[29-34]. 506(25.9%) cycles accepted ICSI and 1450(74.1%) accepted IVF treatment. A total of 11,770 embryos were cultured for blastulation. Early cleavage occurred in 5961(50.6%) embryos. In the end, 7024(59.7%) embryos developed to blastocysts (Table 1 and 2).

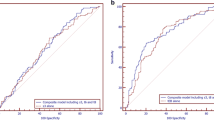

Based on early cleavage and routine observed morphological parameters (cell number, fragmentation, and symmetry), we established a predicting model with GEE. The coefficients and interception was shown in Supplementary Table 1 (Table S1). The GEE model predicted blastocyst formation with an AUC of 0.771(95%CI: 0.768–0.774) in the training set and 0.779(95%CI: 0.77–0.787) in the validation set. A cutoff of 0.51 was determined according to the maximum informedness. The accuracy of prediction according to the cutoff was 74.7%(95%CI: 73.9%-75.5%) in the validation set. Similarly, LASSO regression model and XGboost model based on the combination of cycle characteristics and embryo morphology yielded similar predicting power with AUCs of 0.78(95%CI: 0.771–0.789) and 0.754(95%CI: 0.745–0.763) in validation set, respectively. There was no significant difference in terms of predicting power demonstrated with AUCs among different model (Table 3). The AUC curves and calibration curves were also comparable (Figure S2).

We further explored the discrimination of GEE model with the given cutoff value for blastocyst formation in different subgroup of patients (Table 4). The predicting power in terms of AUCs were similar in the large and denoted a fair performance. However, the discrimination power appeared to be lower in aged patients and patients with fewer oocyte yield.

In clinical practice, whether a blastocyst transfer cycle is canceled may be determined by the availability of all embryos subjected to blastocyst formation in the cycle. To mimic the scenario, we further generated a per-cycle blastocysts prediction based on the models. The predicted number of blastocyst per cycle was simply the sum of individual embryo prediction. For per-cycle blastocyst yield, the predicted number of blastocysts using morphological parameters alone strongly correlated with observed blastocyst number (r = 0.897, P < 0.0001) with a mean absolute error of 0.95 (95%CI: 0.92–0.99).

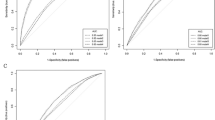

The predicted number of blastocysts was also used to predict chance of blastocyst transfer with an AUC of 0.926((95%CI: 0.911–0.94). The predicting power of the predicted number of blastocysts for blastocyst transfer cancel surpassed an XGBoost model based on 29 features (AUC 0.885, 95%CI: 0.867- 0.903). Figure 1 demonstrated the AUCs and calibration curves of both models. The cycles based model appeared to be overestimate the chance of blastocyst transfer (slope = 1.01, intercept = -0.009) while the predicted number of blastocyst made a prediction closer to observed probability (slope = 1.15, intercept = -0.185).

Performance of embryo based and cycle based model in predicting cycle with blastocyst. A Scatter plot indicating correlation between observed blastocyst number and predicted blastocyst number based on embryo morphology. B ROC curves of embryo based model and cycle based model to predict cycle with blastocyst. C Calibration curves linking predicted probability and observed proportion of cycles with blastocyst according to embryo based and cycle based model

In Table 5, the prediction of blastocyst transfer was stratified according to patient subgroup. The predictive power in terms of AUC of ROC curves was not significantly differ in patients older than 34 years in comparison with the unselected population. On the other hand, the patients with no good quality embryos and the patients with partial embryos cultured suffered a decreased AUC. However, the AUC in the patients with no good quality embryos still suggested a moderate discriminability with a value of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.68–0.79).

Discussion

Although challenged by novel technologies for embryo assessment, the conventional static morphological assessment is still widespread used with established consensus of practice [24, 27], generating large amount of datasets within the past decades. A feasible clinical prediction model based on these datasets may benefit from the large sample size and be easily incorporated in the routine procedures without additional cost. In the present study, we demonstrated the predictive values of conventional static morphological assessment for blastocyst formation and provided a simplified predicting algorithm to predicted canceled blastocyst transfer cycles with a moderate predictive power. In addition, by comparing with models including cycle based parameters, our data also suggested that increase the complexity of the model by taking parameters other than the embryo themselves may not significantly improved the predictive power.

Since the early days of blastocyst culture, many previous studies have investigated the association between conventional morphology assessment and the rates of blastocyst formation [28,29,30]. However, only a few studies quantitatively evaluated the predictive power [16, 18]. Basile et al. evaluated the predictive power for blastocyst formation of morphological criteria defined by the Spanish Association of Embryologists (ASEBIR), showing an AUC of 0.717 (CI95%: 0.703–0.732), which is close to the AUC derived from Eeva time lapse system in the same population. In a classic paper comparing multiple blastocyst formation algorithms, the algorithm based on conventional Istanbul consensus showed an AUC of 0.700 (CI95%: 0.687–0.714), surpassing several time-lapse based algorithms in the same population. Both studies focused on the comparison of different algorithms and the authors may aim at “giving all investigated algorithms equal frames”. Therefore, both time-lapse and conventional morphology results were given as classifications or score groups and the contribution of each conventional morphology parameters were not demonstrated. In addition, the work of Petersen et al. used only the timings part of Istanbul consensus. Comparing with the previous studies, our algorithms based on data-driven models using a full set of conventional morphology parameters. Including conventional morphology parameters rather than pre-established classifications may provide more information and therefore increase the predictive power.

The time-lapse microscopy, which generates thousands of images during the in vitro culture of an embryo, provides far more information than conventional static observation. Theoretically, this advantage may make it a superior morphology tool to predict the fate of a cultured embryo. However, several earlier studies did not demonstrate satisfying predictive power for blastocyst formation, with AUCs ranging from 0.6 to 0.7. More recently, the time-lapse algorithm developed by Motato et al., predicted blastocyst formation with an AUC value 0.849 (95% CI: 0.835–0.854) [17]. This method, however, requires a culture duration up to 96 h, which may resulted in a delayed decision making. A recent study integrates deep learning algorithms to the time-lapse system, and the predictive power in terms of AUC reaches 0.82 [8]. In comparison the historical performance of time-lapse system in predicting blastocyst formation, the conventional static observation of the old era yields acceptable predictive power and only requires limited resource.

Most of the previous morphological studies focused on tracking the destiny of an individual embryo, aiming to select the most competent embryo. On the other hand, whether blastocyst culture yields viable blastocysts for transfer also relates to the decision making. It has been proposed that four good embryos on day 3 may reassure that the patients will benefit from blastocyst transfer [31]. However, the performance of a day 3 morphology based algorithm to predict a canceled blastocyst transfer cycle due to failed blastocyst formation yet to be determined. A few studies used cycle based characteristics, such as maternal age, oocyte yield and the number of good-quality embryos, to predict the probability of blastocyst transfer cancellation [4, 5]. Dessolle et al. established a cycle-based model with multivariate logistical regression and showed a AUC of 0.75 (95% CI: 0.73–0.77) for predicting canceled cycles [4]. More recently, a model using multiple classification algorithms predicted cycle based blastocyst formation with an AUC of 0.922 [5]. Both algorithms require the patient characteristics in combination with embryo quality on day 3. Our data suggested that the cumulative probability of morphological assessment based prediction alone also yields a notable prediction power. Independent of cycle based characteristics, the prediction may be more flexible as it is also applicable to the cycles where only a part of embryos is subjected to blastocyst culture. Interestingly, both our cycle based model and model of Dessolle et al. suggested a tendency of overestimation according to the calibration plots, although different statistic methods and populations were involved. It may suggest a potential intrinsic feature of cycle based prediction.

Prevalence of blastocyst formation in different population may be another issue should be considered beyond discriminability when attempt is made to predict the chance of embryo transfer in a given cycle. The rates of blastocyst formation vary widely among patients, ranging from 0% to almost 100% [1]. In unselected population, the chance to have at least one blastocyst to transfer in a cycle may be rather high. For instance, Dessolle et al. observed that the percentage of cycles with blastocyst transfer was about 79% in the study cohort [4]. We also observed a cycle based blastocyst formation rates approximating 90% in the overall population. With a high prevalence, a naive guessing by always predicting ‘yes’ could still yield high accuracy. On the other hand, however, patients with low embryo yield or advanced age may suffer a higher chance of blastocyst culture failure [2, 3], and need a more detailed consults before making decision. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the discriminability of the model in different subgroup of patients, which may represent different scenarios, and the reasonable AUCs were observed. Notably, a remarkable decrease in blastocyst formation rate was observed among the patients who had no good-quality embryo for blastocyst culture, while a moderate discriminability was observed in the ROC curve. The results suggested that conventional morphology observation remains a useful consulting tool, even no good quality embryo was scored.

It is known that in vitro development of embryos is associated with patient- and treatment-related factors [21]. Beyond the morphology/morphokinetic characteristics, the patient- and treatment-related factors may also affect intrinsic characteristics, such as aneuploidy or metabolism [32, 33]. These characteristics may not be necessarily associated with the appearance of the embryos. Therefore, adding factors such as age may increase the information available for the prediction. To test this hypothesis, we compared the multivariate model including only morphological parameters with models constructed with LASSO regression or XGboost including both morphological parameters and patient/treatment related factors. Although the patient/treatment related factors were significantly associated with blastulation, the LASSO/XGboost models did not significantly surpass the simple multivariate model in terms of predictive power. Well-known prognosis factors for blastocyst formation, such as AMH and maternal age also affected the quantity and morphology of day 3 embryos [34, 35]. The existence of mediation effects, where day 3 embryo quality serve as a mediator, may partially explain why including more patient/treatment related factors may not further improve the performance of the model in the study.

The study is fortified by a large sample size, which may provide a narrow confidence interval for coefficients and reduce the uncertainty of the performance. In addition, we also calibrate the model in several different clinical scenarios, including advanced maternal age, few embryos for culture and blastocyst culture for surplus embryos. The study also suffered from several drawbacks, including retrospective design and subjectivity of methodology. Because the study is single-centered, we could not test the performance of the model in other culture system. Nevertheless, the study may encourage the establishment of predicting model based on existing large datasets in other culture system.

Conclusion

In the present study, data suggested that conventional morphology remained a useful tool to predict blastocyst formation and blastocyst transfer cancellation. Meaningful consult on blastocyst culture could be made on day 3 morning based on a combination of morphological parameters, even though no good quality embryo was obtained at the time.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive M, Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Electronic address aao. Blastocyst culture and transfer in clinically assisted reproduction: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(7):1246–52.

Dirican EK, Olgan S, Sakinci M, Caglar M. Blastocyst versus cleavage transfers: who benefits? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;305(3):749–756

Chen P, Li T, Jia L, Fang C, Liang X. Should all embryos be cultured to blastocyst for advanced maternal age women with low ovarian reserve: a single center retrospective study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(9):761–5.

Dessolle L, Freour T, Barriere P, Darai E, Ravel C, Jean M, et al. A cycle-based model to predict blastocyst transfer cancellation. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(3):598–604.

Spies NC, Pisters EEA, Ball AE, Jungheim ES, Riley JK. A machine learning approach to predict blastocyst formation in vitro. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(4):E47.

Inoue N, Nishida Y, Harada E, Sakai K, Narahara H. GC-MS/MS analysis of metabolites derived from a single human blastocyst. Metabolomics. 2021;17(2):17.

Gallego RD, Remohi J, Meseguer M. Time-lapse imaging: the state of the artdagger. Biol Reprod. 2019;101(6):1146–54.

Liao Q, Zhang Q, Feng X, Huang H, Xu H, Tian B, et al. Development of deep learning algorithms for predicting blastocyst formation and quality by time-lapse monitoring. Commun Bio. 2021;4(1):1–9.

D’Estaing SG, Labrune E, Forcellini M, Edel C, Salle B, Lornage J, et al. A machine learning system with reinforcement capacity for predicting the fate of an ART embryo. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2021;67(1):64–78.

Sayme N, Krebs T, Maas DHA, Kljajic M. Morphokinetics of morula stage embryo fail to predict blastocyst formation and blastocyst quality. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(3):E119.

Zaninovic N, Nohales M, Zhan Q, de los Santos ZMJ, Sierra J, Rosenwaks Z, et al. A comparison of morphokinetic markers predicting blastocyst formation and implantation potential from two large clinical data sets. J Assist Reprod Gen. 2019;36(4):637–46.

Bortoletto P, Kanakasabapathy MK, Thirumalaraju P, Gupta R, Pooniwala R, Souter I, et al. Predicting blastocyst formation of day 3 embryos using a convolutional neural network (CNN): a machine learning approach. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(3):E272–3.

Segal TR, Epstein DC, Lam L, Liu J, Goldfarb JM, Weinerman R. Development of a decision tool to predict blastocyst formation. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):E49–50.

Kim HJ, Yoon HJ, Lee WD, Yoon SH, Lee DH, Kang YJ, et al. Morphokinetics in the early cleavage stage predicts formation and quality of the blastocyst stage. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:230–1.

Kaser DJ, Farland LV, Missmer SA, Racowsky C. Prospective study of automated versus manual annotation of early time-lapse markers in the human preimplantation embryo. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(8):1604–11.

Petersen BM, Boel M, Montag M, Gardner DK. Development of a generally applicable morphokinetic algorithm capable of predicting the implantation potential of embryos transferred on Day 3. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(10):2231–44.

Motato Y, Jose del os Santos M, Jose Escriba M, Aparicio Ruiz B, Remohi J, Meseguer M. Morphokinetic analysis and embryonic prediction for blastocyst formation through an integrated time-lapse system. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(2):376-384.e9.

Basile N, Aparicio-Ruiz B, Garcia Velasco J, de los Santos M, RemohiGimenez J, Meseguer M. Blastocyst formation rate can be predicted by an automatic system independently of the number of oocytes retrieved and the morphology of the embryos on day 3. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):E356.

Milewski R, Kuc P, Kuczynska A, Stankiewicz B, Lukaszuk K, Kuczynski W. A predictive model for blastocyst formation based on morphokinetic parameters in time-lapse monitoring of embryo development. J Assist Reprod Gen. 2015;32(4):571–9.

Coticchio G, Behr B, Campbell A, Meseguer M, Morbeck DE, Pisaturo V, et al. Fertility technologies and how to optimize laboratory performance to support the shortening of time to birth of a healthy singleton: a Delphi consensus. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(5):1021–43.

Kirkegaard K, Sundvall L, Erlandsen M, Hindkjaer JJ, Knudsen UB, Ingerslev HJ. Timing of human preimplantation embryonic development is confounded by embryo origin. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(2):324–31.

Cai J, Liu L, Zhang J, Qiu H, Jiang X, Li P, et al. Low body mass index compromises live birth rate in fresh transfer in vitro fertilization cycles: a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):422-9 e2.

Wang W, Cai J, Liu L, Xu Y, Liu Z, Chen J, et al. Does the transfer of a poor quality embryo with a good quality embryo benefit poor prognosis patients? Reprod Biol Endocrin. 2020;18(1):97.

Alpha Scientists in Reproductive M, Embryology ESIGo. The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1270–83.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1):1–22.

Chen T, He T, Benesty M, Khotilovich V, Tang Y, Cho H, et al. xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting. Version 1.3.2.1 [updated January 2021]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=xgboost. Accessed 1 Mar 2021.

Embryology ESIGo, Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address cbgi. The Vienna consensus: report of an expert meeting on the development of ART laboratory performance indicators. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;35(5):494–510.

Kaupert L, Januario DANF, Czeresnia CE, Nisenbaum MG, Maluf M, Perin PM. Simplified static embryo score system for the prediction of blastocyst formation and euploidy. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):E173.

Fisch JD, Rodriguez H, Ross R, Overby G, Sher G. The Graduated Embryo Score (GES) predicts blastocyst formation and pregnancy rate from cleavage-stage embryos. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(9):1970–5.

Rijnders PM, Jansen CA. The predictive value of day 3 embryo morphology regarding blastocyst formation, pregnancy and implantation rate after day 5 transfer following in-vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(1O):2869–73.

Papanikolaou EG, D’Haeseleer E, Verheyen G, Van de Velde H, Camus M, Van Steirteghem A, et al. Live birth rate is significantly higher after blastocyst transfer than after cleavage-stage embryo transfer when at least four embryos are available on day 3 of embryo culture. A randomized prospective study Hum Reprod. 2005;20(11):3198–203.

Rodriguez-Purata J, Gomez-Cuesta MJ, Cervantes-Bravo E. Association of ovarian stimulation and embryonic aneuploidy in in vitro fertilization cycles with preimplantation genetic testing: A narrative systematic review. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2021. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210069. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34751016.

Franasiak JM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Werner MD, Upham KM, Treff NR, et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):656-63 e1.

Sills ES, Collins GS, Brady AC, Walsh DJ, et al. Bivariate analysis of basal serum anti-Mullerian hormone measurements and human blastocyst development after IVF. Reprod Biol Endocrine. 2011;9:153.

Janny L, Menezo YJ. Maternal age effect on early human embryonic development and blastocyst formation. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;45(1):31–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xinli Wang for her assistance in data processing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 22176159]; the Xiamen medical advantage subspecialty construction project [grant number 2018296] and the Special Fund for Clinical and Scientific Research of Chinese Medical Association [grant number 18010360765].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J., J.C., L.L and J.R. contribute to conception and design. X.J., W.W., J.G., Y.C., Z.L., Z.L. and Jinghua Chen contribute to acquisition of data. X.J. and J.C. contribute to analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contribute to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval of this retrospective study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Medical College Xiamen University on 21 December 2019.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figures S1. Distribution of blastulation rate among different day 3 embryos with different cell number in the training data. Error bar indicates 95% CI of the rates.

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Performance of models in predicting blastocyst formation. (A) ROC curves for models (B) Calibration plot linking predicted probabilities to observed rates rates.

Additional file 3:

Table S1. Model coefficients of GEE and LASSO model to predict blastocyst formation.

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Cai, J., Liu, L. et al. Does conventional morphological evaluation still play a role in predicting blastocyst formation?. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 20, 68 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-022-00945-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-022-00945-y