Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism in young women. Excessive ovarian production of Anti-Müllerian Hormone, secreted by growing follicles in excess, is now considered as an important feature of PCOS. The aim of this review is first to update the current knowledge about the role of AMH in the pathophysiology of PCOS. Then, this review will discuss the improvement that serum AMH assay brings in the diagnosis of PCOS. Last, this review will explain the utility of serum AMH assay in the management of infertility in women with PCOS and its utility as a marker of treatment efficiency on PCOS symptoms. It must be emphasized however that the lack of an international standard for the serum AMH assay, mainly because of technical issues, makes it difficult to define consensual thresholds, and thus impairs the widespread use of this new ovarian marker. Hopefully, this should soon improve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism in young women and affects 5 to 10 % of the female population. Since 2003, the Rotterdam Consensus defines PCOS and considers the antral follicle count (AFC) on ultrasound as one of the diagnostic criteria. With the improvement in ultrasonographic technology, the number of follicles seen on ultrasound increases almost daily but remains dependent on the specific equipment. Serum AMH is synthetized by small antral follicles, which are precisely the ones seen on ultrasound. Serum AMH could therefore be used as a surrogate for the AFC in the diagnosis of PCOS. Serum AMH has also demonstrated its utility in the treatment of infertility. But the absence of an international standard for serum AMH assay and the inability to define thresholds makes application of serum AMH more difficult. The purpose of this review is to explain the relationship between AMH and PCOS and to describe the utility of serum AMH in the diagnosis and treatment of PCOS.

AMH: from physiology to ovarian assessment

Physiology of AMH

AMH was only isolated and purified in 1984. Genes for AMH and its receptor were sequenced and cloned in 1986 and 1994 respectively [1]. AMH has been predominantly known for its role in male sexual differentiation [2]. In women, AMH expression is restricted to one cell type: the granulosa cells of the ovary. It starts around the 25th week of gestation continuing until menopause [1, 3]. AMH is expressed at all steps of folliculogenesis. It is initiated as soon as primordial follicles are recruited to grow into small preantral follicles and its highest expression is observed in pre antral and small antral follicles. AMH expression then decreases with the selection of follicles for dominance and is no longer expressed during the FSH dependent stages of follicular growth (except in the cumulus cells of pre ovulatory follicles), or in atretic follicles [4, 5] (Fig. 1).

Schematic model of AMH actions in the ovary. Dewailly, D., et al., Hum Reprod Update, 2014 [24]. AMH, produced by the granulosa cells of small growing follicles, inhibits initial follicle recruitment and FSH-dependent growth and selection of pre antral and small antral follicles. In addition, AMH remains highly expressed in cumulus cells of mature follicles. The inset shows in more detail the inhibitory effect of AMH on FSH-induced CYP19a1 expression leading to reduced estradiol (E2) levels, and the inhibitory effect of E2 itself on AMH expression. T, testosterone; Cyp19a1, aromatase. Figure modified from van Houten et al. (2010)

The functional role of AMH in early follicular growth has been characterized by the study of “knocked out” models for the AMH gene (AMHKO) [5, 8–10]. When there is no AMH, primordial follicles are recruited faster, resulting in more growing follicles until the exhaustion of primary follicle pool at younger age than wild-type animals. AMH therefore has an inhibitory effect on early follicular recruitment preventing the entry of primordial follicles into the growing pool and thus premature exhaustion of follicles/oocytes [11]. AMH also has an inhibitory effect on cyclic follicular recruitment in vivo by reducing the follicle sensitivity to FSH. In vitro AMH inhibits FSH induced pre antral follicle growth [4, 5, 8, 9].

AMH also reduces the number of LH receptors in granulosa cells, also an FSH induced process [12]. Thus, it is clear that AMH is involved in the regulation of follicle growth initiation and in the threshold for follicle FSH sensitivity.

AMH assay

In clinical application, AMH presents many opportunities but unfortunately there are difficulties due to several biological features of this molecule [13]. First, there is a molecular heterogeneity of the circulating AMH level with a non-cleaved biologically inactive form and a cleaved biologically active form [14, 15]. Also, there is variable sensitivity of the immunoassays to interference by complement C1q and C3 [16]. Then, the stability of AMH samples during the storage is not well known [17]. Moreover, AMH concentration varies according to the situation: in adults they are low (from 10.7 to 98 pmol/L) whereas in male new-borns they are very high (749 to 1930 pmol/L) [13]. Measurement thus involves different assays with different sensitivities. The last but not the least technical problem is the inter-laboratory variability, mainly for low values of serum AMH. The difficulty lies in the fact there are currently different ELISA immunoassays used worldwide: the Gen II (Beckman Coulter), the EIA AMH/MHS kits (IOT or “Immunotech” Beckman Coulter) and the AL-105-i (Anshlabs), which use different monoclonal antibody and different standards [18]. The lack of agreement between these assays explains the absence of consensual reference values and decision thresholds between teams in the literature [11]. To maximize the clinical utility of serum AMH measurement, current progress has been made: development of an ultrasensitive essay (‘pico AMH’ kit, Anshlabs), and automation on immuno-analyzers (Access Dxi automatic analyzer, Beckman Coulter. Cobas e instrument, Roche Diagnostics) allowing nearly identical values [19, 20]. Now that AMH assay has been automated, it is with great anticipation that an international standard for serum AMH will be developed.

AMH as indicator of ovarian reserve and follicle growth

The ovarian reserve refers to the number of primordial follicles, defined at birth (around 1 million). This follicular capital decreases gradually throughout reproductive life, with the continuous initiation of growth of some follicles, and then mostly their apoptosis. There are about 400 000 follicles in adolescents’ ovaries (leading roughly to 400 ovulations), whereas only a thousand remains at the time of Menopause.

Serum AMH concentration is strongly correlated with the number of growing follicles since it represents AMH secretion from all developing follicles [21, 22]. Considering that the rate of initiation of follicle growth is deeply related to the initial follicular pool, we can assume that serum AMH is an indirect reflection of ovarian reserve. There is actually a very good correlation between serum AMH levels and ultrasonographic measure of the antral follicular count (AFC) [23, 24]. This can be explained because circulating AMH is mostly produced by granulosa cells of follicles from 2 to 9 mm in diameter (60 %), and those small follicles are precisely the ones counted on the ultrasound when the AFC is done [25]. Measurement of serum AMH is even more sensitive and specific than the AFC as it also reflects pre antral and small antral follicles (<2 mm), which are hardly seen in ultrasound. Serum AMH is therefore a deeper “probe” for the growing follicular pool than the AFC [6].

Serum AMH assay has many benefits over the other markers of ovarian reserve [11]. First, its plasmatic level is quite stable from one cycle to another and throughout the same cycle since the dominant follicle and corpus luteum do not secrete AMH [26, 27]. Conversely, the AFC and the FSH E2 pair have to be measured on the first 5 days of the cycle [28–30]. Also, a recent study has shown ethnicity does not influence serum AMH level, contrary to previous studies [31]. Besides its minor variability, serum AMH is also useful when the AFC cannot be done such as in obese, virgin or poorly echogenic patients [6]. Moreover, serum AMH level is rather independent from the hypothalamic pituitary axis and as such is not modified in pathologies such as hyperprolactinemia, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea or in incomplete and recent hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, providing serum FSH level remains normal or sub-normal [32]. The question thus actually arises about the replacement of the conventional markers of ovarian reserve by the AMH assay [33].

However, serum AMH can be influenced by many factors and some controversies persist. Obesity is often associated with a significantly lower level of serum AMH, but not in all studies [11, 34, 35]. There is also a controversy regarding the influence of hormonal contraception: to some authors, combined oestrogen progestin does not change AMH serum levels whereas others have recently reported a decrease of 29 to 50 % that could be explained by the suppression of gonadotropin secretion [36–40]. Similarly a decrease of serum AMH seven days after injection of depot leuprolide 3.75 mg, a GnRH agonist has been shown [41].

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and AMH

Definition

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism in young women and affects 5 to 10 % of the female population [42, 43]. PCOS is a diagnosis of exclusion and is defined by the Rotterdam classification (2003) [44] requiring at least 2 out of the 3 following characteristics: (i) cycle disorder, (ii) clinical or biological hyperandrogenism, (iii) antral follicular excess on ultrasound with ≥ 12 follicles from 2 to 9 mm per ovary and/or ovarian volume ≥ 10 ml. Metabolic disorders are often associated to PCOS (up to 50 %), including an increased rate of insulin resistance, regardless obesity [45]. PCOS thus imposes a considerable economic burden on national health systems [46]. PCOS is almost certainly a genetic condition but the precise causes of hyperandrogenism and anovulation, which are not always associated, are still under investigations [47, 48].

Pathophysiology

PCOS is characterized by an increased number of follicles at all growing stages [49–51]. This increase is particularly seen in the pre-antral and small antral follicles, those which primarily produce AMH [52, 53]. Thus elevated serum AMH level, as a reflection of the stock of pre antral and small antral follicles, is 2–4 fold higher in women with PCOS than in healthy women [54–57] and is found in all PCOS populations [21, 22].

This increase in serum AMH was first thought to be only due to the higher number of pre antral and small antral follicles. However, production of AMH by granulosa cells was found in vitro to be 75-fold higher in anovulatory PCOS and 20-fold higher in normo ovulatory PCOS than in normal ovaries [55]. This suggests increased serum AMH levels in PCOS would also reflect an intrinsic dysregulation of the granulosa cells, in which AMH, itself, could be involved since an over expression of the AMH receptor type II (AMHRII) has also been demonstrated [58, 59].

The cause of such high production of AMH in antral follicles from PCO is currently unknown, but there is evidence to support a role played by androgens. Indeed, a positive correlation between serum androgen and AMH levels has been reported and the over production of androgens could be an intrinsic defect of thecal cells in PCOS [21, 22, 60–62].

Studies demonstrated contradictory results concerning AMH regulation by gonadotropins. For some authors, gonadotropins (especially FSH) inhibit serum AMH production in vivo in normal ovaries [63, 64]. Pellat et al. [55] also demonstrated a reduced AMH production in granulosa cells from women with PCOS stimulated by FSH, but no such effect was found in ‘normal’ women. On the contrary, others demonstrated a stimulating effect of FSH on AMH expression in normal ovaries as well as in PCOS [65]. The recent finding that E2 inhibits AMH expression could reconcile those different results [66]: FSH may directly stimulate AMH in small antral follicles, as long as they do not express aromatase. But in larger follicles, by increasing E2 production with the recruitment of a dominant follicle, FSH would have an indirect inhibitory effect on AMH expression through the negative feedback of E2 (Fig. 2).

Schematic diagram of AMH regulation by FSH and E2 in GC of small and large antral follicles. Adapted from Grynberg M et al. JCEM, 2012 [65]. Until the small antral stage, AMH secretion is stimulated by different factors like FSH. Estradiol (E2) production under the influence of FSH is impaired by the inhibiting effect of AMH on aromatase. When estradiol concentration reaches a certain threshold in large antral follicles, it is capable of completely inhibiting AMH expression through ERβ, which predominates in growing follicles, thus overcoming the stimulation by FSH. In large follicles from PCO, the lack of FSH-induced E2 production and the high level of AMH impair the shift form the AMH to the E2 tone, thus leading to the follicular arrest

It has also been demonstrated that AMH significantly decreases not only the FSH receptor expression but also ovarian aromatase expression [18]. This allows protection of the small follicles from premature aromatase expression. However, when this protective effect exceeds its physiological role, because of AMH excess and/or because it lasts longer than it should in larger follicles, this could result in a defect in the selection of the dominant follicle, thus causing the so called the “follicular arrest”. The fact that AMH is inhibitory to FSH-dependent factors required for follicle dominance adds considerable significance to the high serum AMH expression found in PCOS and makes AMH a putative central actor of the ‘follicular arrest’. In good agreement, clinical studies have shown a relationship between high AMH and ovulatory disorder [55]. Likewise LH seems to stimulate AMH production by the granulosa cells in women with PCOS [55]. Acquisition of LH receptors by the granulosa cells happens sooner in PCOS [67]. In addition, some authors demonstrated that LH reduces AMHRII expression in granulosa luteal cells in normal ovaries and in women with normo-ovulatory PCOS, whereas it cannot do so in women with anovulatory PCOS [65, 68]. Besides LH stimulating effect on AMH expression, this lack of LH-induced down regulation of AMHRII expression in women with anovulatory PCOS could contribute to anovulation. Therefore, the premature action of LH might also contribute to the ‘follicular arrest’ through a mechanism involving the AMH system [67, 69].

To sum up, in PCOS, there are many abnormalities of folliculogenesis: (i) an increased number of small growing follicles [50], (ii) an inhibition of the terminal follicular growth [51], resulting in a lack of selection of the dominant follicle, so-called the “follicle arrest” [70], and (iii) a follicular apoptosis defect aggravating the excess of growing follicles [71, 72].

Serum AMH in the diagnosis of PCOS

Given its strong implication in the pathophysiology of PCOS, serum AMH could be considered the “Gold Standard” in the diagnosis of PCOS. Even though serum AMH would be theoretically more accurate than AFC, as it reflects also the excess of small follicles non-visible on ultrasound [25, 6, 73] (Fig. 3), it is still considered premature to make this diagnostic transition.

Rationale for the use of serum AMH assay as a probe for PCOM. Dewailly, D., et al., Hum Reprod Update, 2014 [24]. a All growing follicles secrete AMH but serum AMH reflects only the secretion from bigger follicles that are in contact with the vascular bed. As the numbers of follicles in all growth stages are strongly related to each other, serum AMH is considered to reflect the sum of growing follicles but not the number of primordial follicles that do not secrete AMH. b In PCO, the numbers of all growing follicles is increased, resulting in a marked increase in serum AMH level. AMH may be considered as a deeper and more sensitive probe to define follicle excess than the follicle count by ultrasound (U/S) since it appraises more follicle classes (blue arrows)

The robust association between AMH and AFC has led some authors to compare their performance in the diagnosis of PCOS [74]. However, the results from the current literature are not homogeneous [11]. Part of this heterogeneity is due to the lack of well-defined population. In particular, some authors have used the PCOS definition established in 2003 at the Rotterdam conference, using 12 follicles of 2–9 mm diameter per ovary for the polycystic ovaries morphology (PCOM) [75]. This cut off is highly dependent on ultrasound equipment and operator skill, as demonstrated by Dewailly et al. [76]. Therefore, with the latest ultrasound generation, the threshold has evolved and is now up to 19 or 25 [73, 77, 78]. This threshold will probably continue to increase as newer ultrasound technologies and equipment are developed. Additionally, there are critical issues regarding what populations are included or excluded in the normative population. Lastly, there are technical issues regarding serum AMH assays leading to further heterogeneity of the results in the literature.

It is therefore impossible, so far, to propose a consensual and universal diagnostic threshold for serum AHM in the prediction of PCOS. However, in our experience, a cut off at 35 pmol/L (4.9 ng/mL) with the enzyme immunoassay AMH-EIA (EIA AMH/MIS kit) (“Immunotech”, ref A16507) provided by Beckman Coulter (France) had a good specificity (97 %) and a better sensitivity than the AFC (92 %) to distinguish women with PCOS from normal women [73]. This result was obtained after exclusion of women with asymptomatic PCO from the control group through cluster analysis, a mathematical procedure that avoids using predefined thresholds for AMH and AFC. This approach has been replicated in another setting [77]. Pigny et al. (unpublished data) have also compared the five serum AMH assays (as described above) for the diagnosis of PCOS. They proposed, with manual ELISAs assays, a higher cut-off at 5.6 ng/mL (40 pmol/L), as biological criteria indicative of PCOM, corresponding to the 95th percentile of “pure” controls. They also proposed a threshold at 4.2 ng/mL (30 pmol/L) for the automatic assays (unpublished data). If confirmed with the new automatized serum AMH assays or the ultrasensitive assay, a high serum AMH level could then become a reliable and accurate marker for PCOM, and eventually replace the AFC, which also suffers from great controversy in the literature. As an ‘increased serum AMH’ does not refer to ovarian morphology, the acronym ‘PCOM’ would not be appropriate and we have therefore suggested the term “PCO-like abnormality” (i.e., PCOM and/or increased serum AMH) as the third item of the Rotterdam classification rather than ‘PCOM’ [79, 74].

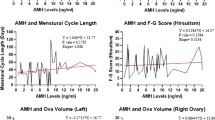

Serum AMH level is also correlated to the severity of PCOS symptoms [68] and is higher when hyperandrogenism [62, 80] or oligo-anovulation is present [21, 55, 81]. By a principal component analysis, it has been shown a high serum AMH level can be considered as a marker of hyperandrogenism and could also be used as a substitute for this item in the Rotterdam classification [82].

This would reconcile the different classifications currently available for PCOS because some require hyperandrogenism as a necessary criterion [56]. We thus propose the following strategy: for the diagnosis of PCOS, hyperandrogenism and oligo anovulation should be first sought, after excluding all alternative diagnoses. If one is missing, a high AFC or/and AMH level could be used instead.

In adolescent and young women with PCOS, it is sometimes difficult to evaluate the ovaries on ultrasonography. It can also be difficult to estimate the share of the physiological and pathological, concerning acne and cycle disorders. Serum AMH assay is therefore a true alternative, as it is recommended by the American association of clinical endocrinologists [83]. Adolescents with PCOS have higher serum AMH levels, with a thresholds set at 30 pmol/L [84], which is in the range of values found in the literature for older PCOS women [85, 86].

However, it must be noticed that the thresholds for excessive AFC or high serum AMH level have to be reviewed and validated worldwide, since recent technical developments in ultrasound and assays could lead to their modification. In the meantime, it is recommended that each centre set its own thresholds.

THE use of serum AMH for the treatment of PCOS

AMH: useful in treatments of infertility?

Because of the dysovulation often associated, PCOS is a frequent cause of infertility. The follicular excess present in this pathology can be responsible for an ovarian over-response when induction ovulation treatments are used increasing risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). This is a challenging situation as the minimal effective dose is often very close to the overdose leading to hyperstimultation.

Thus, in addition to its diagnostic role, serum AMH level is useful to establish treatment protocols and to define the best strategy for ovulation induction in infertile women with PCOS.

Clomiphene citrate

So far, there are very few studies that have examined the predictive power of serum AMH level in the response to clomiphene citrate (CC). Mahran et al. [87] have proposed a threshold at 3.4 ng/mL above which a resistance to CC is highly expected, suggesting a higher starting dose should be used. However, the free androgen index was significantly higher among the non-responding patients which may have biased the results since this parameter is a well-known negative predictor. Also the sensitivity and specificity were poor (around 75 %), leading to wrong information in ¼ of cases, making difficult the use of this threshold in clinical practice.

Recombinant FSH

Serum AMH level appears to be a good predictive marker for the risk of OHSS [88], mostly occurring in PCOS, as proved in the meta-analysis of Broer et al. [89]. However the establishment of an accurate threshold remains difficult because of the heterogeneity of the OHSS definition and technical issues with the AMH assays.

To conclude, serum AMH determination may be a helpful tool in the prediction of the ovarian response to gonadotropins in PCOS. Difficulties persist, however, since there is no consensus on the threshold for the AMH values. This is due to the well-known difficulty of quantification and standardization of the AMH assays.

Ovarian drilling

Laparoscopic ovarian drilling (LOD) is currently recommended as a successful second line treatment for ovulation induction in women with PCOS. It is considered to be an alternative to gonadotropin stimulation in the case of CC resistance [90].

The aim is to trigger spontaneous ovulation by destroying small amounts of ovarian cortex. The physiological mechanism remains unknown, but drilling significantly alters the hormonal environment within the ovary. The utility of the AMH assay as a predictor for LOD outcome has been recently questioned [91]. Two studies evaluated serum AMH before LOD to correlate with the results in terms of spontaneous ovulation [92, 93]. Elsmashad et al. [92] evaluated the effect of LOD, in PCOS, on serum AMH and ovarian stromal blood flow changes, by using three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography. They showed LOD was followed by lower serum AMH levels and less elevated Doppler flow indices. Amer et al. [93] also showed that women who ovulated after LOD had lower pre-operative AMH levels. They identified a pretreatment AMH level cut-off of 7.7 ng/mL (sensitivity 78 %, specificity 76 %), which predicted failure of LOD. Weaknesses of this study included the small sample size and the fact LOD was used as a first line method for ovulation induction

AMH: a marker of treatment efficiency on PCOS symptoms?

To normalize the menstrual cycle, it is common to prescribe a hormonal contraception to women with PCOS. As explained above, there is, however, controversy regarding the impact of hormonal contraception on the AMH circulating level [6, 38]. In PCOS, it has recently been shown [94] that in current users of hormonal contraception, SHBG was increased, leading to a diminished bioavailable androgen level, and that AMH and AFC levels were decreased. However, no study has reported so far this decrease of serum AMH has a predictive value on the subsequent fertility.

To have an anti-androgenic effect and thus decrease the clinical hyperandrogenism (such as acne, hirsutism) it is common, in PCOS, to use oral combined contraceptive treatment sometimes combined with antiandrogens such as drospirenone or cyproterone acetate (CPA) or spironolactone [95, 96]. Panidis et al. [97] have shown a significant decrease in serum AMH levels in women with PCOS with ethinylestradiol + CPA but not with use of ethinylestradiol + drospirenone.

Some studies have evaluated the relationship between weight loss, menstrual cyclicity and serum AMH levels in overweight women with PCOS. Moran et al. [98] showed better menstrual improvement after weight loss in women with lower baseline serum AMH. Serum AMH could therefore be used as a potential predictive factor of cycle normalization after weight loss. Nybacka et al. [99] described a significant decrease in serum AMH levels after diet in obese women with PCOS. Thomson et al. [100] demonstrated long-term weight loss (twenty weeks) resulted in improvements in reproductive function but did not change serum AMH levels. Lastly, various effects on AMH level were obtained with Metformin usage in women with PCOS [97, 101–104].

Altogether, no threshold for serum AMH can be proposed to predict the effectiveness of these treatments.

Conclusion

It is now undeniable that serum AMH is a valuable tool for the diagnosis of PCOS. As for its benefit in the treatment of PCOS, there may be an advantage in therapeutic decision support, but this needs to be confirmed by further studies. However, the current technical difficulties to set up consensual serum AMH thresholds [105, 19] (stability and heterogeneity of circulating AMH, wide range of values, inter laboratory variability, different immunoassays used worldwide) may have curbed the enthusiasm of some clinicians to make it “THE” marker of PCOM. However, we must remain optimistic regarding the latest progress made, making it more and more realistic that this assay may, one day, replace the AFC in the Rotterdam classification.

References

Rajpert-De Meyts E, Jorgensen N, Graem N, Muller J, Cate RL, Skakkebaek NE. Expression of anti-Mullerian hormone during normal and pathological gonadal development: association with differentiation of Sertoli and granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(10):3836–44. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.10.6047.

Jost A. The age factor in the castration of male rabbit fetuses. Exp Biol Med. 1947;66(2):302.

Kuiri-Hanninen T, Kallio S, Seuri R, Tyrvainen E, Liakka A, Tapanainen J, et al. Postnatal developmental changes in the pituitary-ovarian axis in preterm and term infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):3432–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1502.

Salmon NA, Handyside AH, Joyce IM. Oocyte regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone expression in granulosa cells during ovarian follicle development in mice. Dev Biol. 2004;266(1):201–8.

Durlinger AL, Visser JA, Themmen AP. Regulation of ovarian function: the role of anti-Mullerian hormone. Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2002;124(5):601–9.

Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):370–85. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt062.

van Houten EL, Themmen AP, Visser JA. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH): regulator and marker of ovarian function. Annales d'endocrinologie. 2010;71(3):191–7. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2010.02.016.

Durlinger AL, Kramer P, Karels B, de Jong FH, Uilenbroek JT, Grootegoed JA, et al. Control of primordial follicle recruitment by anti-Mullerian hormone in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 1999;140(12):5789–96. doi:10.1210/endo.140.12.7204.

Durlinger AL, Gruijters MJ, Kramer P, Karels B, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone attenuates the effects of FSH on follicle development in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 2001;142(11):4891–9. doi:10.1210/endo.142.11.8486.

Durlinger AL, Gruijters MJ, Kramer P, Karels B, Ingraham HA, Nachtigal MW, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone inhibits initiation of primordial follicle growth in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):1076–84.

Iliodromiti S, Kelsey TW, Anderson RA, Nelson SM. Can anti-Mullerian hormone predict the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome? A systematic review and meta-analysis of extracted data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):3332–40. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1393.

Teixeira J, Maheswaran S, Donahoe PK. Mullerian inhibiting substance: an instructive developmental hormone with diagnostic and possible therapeutic applications. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(5):657–74. doi:10.1210/edrv.22.5.0445.

Pigny P. Anti-Mullerian hormone assay : what's up in 2013? Médecine de la reproduction. Gynécologie Endocrinologie. 2014;16(1):16–20.

Pankhurst MW, McLennan IS. Human blood contains both the uncleaved precursor of anti-Mullerian hormone and a complex of the NH2- and COOH-terminal peptides. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(10):E1241–7. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00395.2013.

Nachtigal MW, Ingraham HA. Bioactivation of Mullerian inhibiting substance during gonadal development by a kex2/subtilisin-like endoprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):7711–6.

Han X, McShane M, Sahertian R, White C, Ledger W. Pre-mixing serum samples with assay buffer is a prerequisite for reproducible anti-Mullerian hormone measurement using the Beckman Coulter Gen II assay. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2014;29(5):1042–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu050.

Rustamov O, Smith A, Roberts SA, Yates AP, Fitzgerald C, Krishnan M, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone: poor assay reproducibility in a large cohort of subjects suggests sample instability. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27(10):3085–91. doi:10.1093/humrep/des260.

Pellatt L, Rice S, Dilaver N, Heshri A, Galea R, Brincat M, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone reduces follicle sensitivity to follicle-stimulating hormone in human granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(5):1246–51,e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.015.

van Helden J, Weiskirchen R. Performance of the two new fully automated anti-Mullerian hormone immunoassays compared with the clinical standard assay. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015;30(8):1918–26. doi:10.1093/humrep/dev127.

Nelson SM, Pastuszek E, Kloss G, Malinowska I, Liss J, Lukaszuk A, et al. Two new automated, compared with two enzyme-linked immunosorbent, antimullerian hormone assays. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):1016-21.e6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.024.

Laven JS, Mulders AG, Visser JA, Themmen AP, De Jong FH, Fauser BC. Anti-Mullerian hormone serum concentrations in normoovulatory and anovulatory women of reproductive age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(1):318–23. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030932.

Pigny P, Merlen E, Robert Y, Cortet-Rudelli C, Decanter C, Jonard S, et al. Elevated serum level of anti-mullerian hormone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to the ovarian follicle excess and to the follicular arrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5957–62. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030727.

van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, te Velde ER, Fauser BC, Bancsi LF, de Jong FH, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2002;17(12):3065–71.

Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Guibourdenche J, Frydman R, Taieb J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone is more strongly related to ovarian follicular status than serum inhibin B, estradiol, FSH and LH on day 3. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2003;18(2):323–7.

Jeppesen JV, Anderson RA, Kelsey TW, Christiansen SL, Kristensen SG, Jayaprakasan K, et al. Which follicles make the most anti-Mullerian hormone in humans? Evidence for an abrupt decline in AMH production at the time of follicle selection. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19(8):519–27. doi:10.1093/molehr/gat024.

Fanchin R, Taieb J, Lozano DH, Ducot B, Frydman R, Bouyer J. High reproducibility of serum anti-Mullerian hormone measurements suggests a multi-staged follicular secretion and strengthens its role in the assessment of ovarian follicular status. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2005;20(4):923–7. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh688.

van Disseldorp J, Lambalk CB, Kwee J, Looman CW, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC, et al. Comparison of inter- and intra-cycle variability of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle counts. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2010;25(1):221–7. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep366.

Hehenkamp WJ, Looman CW, Themmen AP, de Jong FH, Te Velde ER, Broekmans FJ. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels in the spontaneous menstrual cycle do not show substantial fluctuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):4057–63. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0331.

La Marca A, Stabile G, Artenisio AC, Volpe A. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone throughout the human menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2006;21(12):3103–7. doi:10.1093/humrep/del291.

Tsepelidis S, Devreker F, Demeestere I, Flahaut A, Gervy C, Englert Y. Stable serum levels of anti-Mullerian hormone during the menstrual cycle: a prospective study in normo-ovulatory women. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2007;22(7):1837–40. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem101.

Bhide P, Gudi A, Shah A, Homburg R. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels across different ethnic groups: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;122(12):1625–9. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13103.

Tran ND, Cedars MI, Rosen MP. The role of anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) in assessing ovarian reserve. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(12):3609–14. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0368.

La Marca A, Broekmans FJ, Volpe A, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Table ESIGfRE--AR. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH): what do we still need to know? Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2009;24(9):2264–75. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep210.

Freeman EW, Gracia CR, Sammel MD, Lin H, Lim LC, Strauss 3rd JF. Association of anti-mullerian hormone levels with obesity in late reproductive-age women. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(1):101–6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.074.

Steiner AZ, Stanczyk FZ, Patel S, Edelman A. Antimullerian hormone and obesity: insights in oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2010;81(3):245–8. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.10.004.

Bentzen JG, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Lidegaard O, Larsen EC, Friis-Hansen L, et al. Ovarian reserve parameters: a comparison between users and non-users of hormonal contraception. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):612–9. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.09.001.

Somunkiran A, Yavuz T, Yucel O, Ozdemir I. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels during hormonal contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134(2):196–201. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.01.012.

La Marca A, Malmusi S, Giulini S, Tamaro LF, Orvieto R, Levratti P, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone plasma levels in spontaneous menstrual cycle and during treatment with FSH to induce ovulation. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2004;19(12):2738–41. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh508.

Dolleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dolle ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, et al. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Mullerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2106–15. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3995.

Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, Vaskivuo T, Piltonen T, Tapanainen JS. Antimullerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1305–10. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.034.

Su HI, Maas K, Sluss PM, Chang RJ, Hall JE, Joffe H. The impact of depot GnRH agonist on AMH levels in healthy reproductive-aged women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):E1961–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2410.

Franks S. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(13):853–61. doi:10.1056/nejm199509283331307.

Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, Hickey TE. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370(9588):685–97. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61345-2.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2004;19(1):41–7.

Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A. Profound peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 1989;38(9):1165–74.

Azziz R, Marin C, Hoq L, Badamgarav E, Song P. Health care-related economic burden of the polycystic ovary syndrome during the reproductive life span. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4650–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0628.

Cui L, Li G, Zhong W, Bian Y, Su S, Sheng Y, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms in women with a single PCOS clinical feature. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu361.

Kosova G, Urbanek M. Genetics of the polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;373(1-2):29–38. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.009.

Hughesdon PE. Morphology and morphogenesis of the Stein-Leventhal ovary and of so-called “hyperthecosis”. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37(2):59–77.

Webber LJ, Stubbs S, Stark J, Trew GH, Margara R, Hardy K, et al. Formation and early development of follicles in the polycystic ovary. Lancet. 2003;362(9389):1017–21.

Maciel GA, Baracat EC, Benda JA, Markham SM, Hensinger K, Chang RJ, et al. Stockpiling of transitional and classic primary follicles in ovaries of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(11):5321–7.

Weenen C, Laven JS, Von Bergh AR, Cranfield M, Groome NP, Visser JA, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(2):77–83.

Bhide P, Dilgil M, Gudi A, Shah A, Akwaa C, Homburg R. Each small antral follicle in ovaries of women with polycystic ovary syndrome produces more antimullerian hormone than its counterpart in a normal ovary: an observational cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.033.

Lie Fong S, Schipper I, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Visser JA, Laven JS. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone and inhibin B concentrations are not useful predictors of ovarian response during ovulation induction treatment with recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):459–63. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.084.

Pellatt L, Hanna L, Brincat M, Galea R, Brain H, Whitehead S, et al. Granulosa cell production of anti-Mullerian hormone is increased in polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):240–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1582.

Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, et al. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):456–88.

Villarroel C, Merino PM, Lopez P, Eyzaguirre FC, Van Velzen A, Iniguez G, et al. Polycystic ovarian morphology in adolescents with regular menstrual cycles is associated with elevated anti-Mullerian hormone. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2011;26(10):2861–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/der223.

Catteau-Jonard S, Jamin SP, Leclerc A, Gonzales J, Dewailly D, di Clemente N. Anti-Mullerian hormone, its receptor, FSH receptor, and androgen receptor genes are overexpressed by granulosa cells from stimulated follicles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4456–61. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1231.

Alebic MS, Stojanovic N, Duhamel A, Dewailly D. The phenotypic diversity in per-follicle anti-Mullerian hormone production in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015. doi:10.1093/humrep/dev131.

Gilling-Smith C, Willis DS, Beard RW, Franks S. Hypersecretion of androstenedione by isolated thecal cells from polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(4):1158–65.

Carlsen SM, Vanky E, Fleming R. Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in androgen-suppressed women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2009;24(7):1732–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep074.

Eldar-Geva T, Margalioth EJ, Gal M, Ben-Chetrit A, Algur N, Zylber-Haran E, et al. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women with polycystic ovaries with and without hyperandrogenism. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2005;20(7):1814–9.

Baarends WM, Uilenbroek JT, Kramer P, Hoogerbrugge JW, van Leeuwen EC, Themmen AP, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone and anti-mullerian hormone type II receptor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in rat ovaries during postnatal development, the estrous cycle, and gonadotropin-induced follicle growth. Endocrinology. 1995;136(11):4951–62.

Panidis D, Katsikis I, Karkanaki A, Piouka A, Armeni AK, Georgopoulos NA. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels are differentially modulated by both serum gonadotropins and not only by serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(4):649–53. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2011.07.005.

Pierre A, Peigne M, Grynberg M, Arouche N, Taieb J, Hesters L, et al. Loss of LH-induced down-regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone receptor expression may contribute to anovulation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2013;28(3):762–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/des460.

Grynberg M, Pierre A, Rey R, Leclerc A, Arouche N, Hesters L, et al. Differential regulation of ovarian anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) by estradiol through alpha- and beta-estrogen receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1649–57. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3133.

Willis DS, Watson H, Mason HD, Galea R, Brincat M, Franks S. Premature response to luteinizing hormone of granulosa cells from anovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome: relevance to mechanism of anovulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(11):3984–91. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.11.5232.

Pellatt L, Rice S, Mason HD. Anti-Mullerian hormone and polycystic ovary syndrome: a mountain too high? Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2010;139(5):825–33. doi:10.1530/REP-09-0415.

Jakimiuk AJ, Weitsman SR, Navab A, Magoffin DA. Luteinizing hormone receptor, steroidogenesis acute regulatory protein, and steroidogenic enzyme messenger ribonucleic acids are overexpressed in thecal and granulosa cells from polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(3):1318–23. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.3.7318.

Jonard S, Dewailly D. The follicular excess in polycystic ovaries, due to intra-ovarian hyperandrogenism, may be the main culprit for the follicular arrest. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10(2):107–17. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmh010.

Das M, Djahanbakhch O, Hacihanefioglu B, Saridogan E, Ikram M, Ghali L, et al. Granulosa cell survival and proliferation are altered in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):881–7. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1650.

Webber LJ, Stubbs SA, Stark J, Margara RA, Trew GH, Lavery SA, et al. Prolonged survival in culture of preantral follicles from polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(5):1975–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1422.

Dewailly D, Gronier H, Poncelet E, Robin G, Leroy M, Pigny P, et al. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): revisiting the threshold values of follicle count on ultrasound and of the serum AMH level for the definition of polycystic ovaries. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2011;26(11):3123–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/der297.

Eilertsen TB, Vanky E, Carlsen SM. Anti-Mullerian hormone in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: can morphologic description be replaced? Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27(8):2494–502. doi:10.1093/humrep/des213.

Balen AH, Laven JS, Tan SL, Dewailly D. Ultrasound assessment of the polycystic ovary: international consensus definitions. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9(6):505–14.

Dewailly D, Alebic MS, Duhamel A, Stojanovic N. Using cluster analysis to identify a homogeneous subpopulation of women with polycystic ovarian morphology in a population of non-hyperandrogenic women with regular menstrual cycles. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2014;29(11):2536–43. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu242.

Dewailly D, Lujan ME, Carmina E, Cedars MI, Laven J, Norman RJ, et al. Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):334–52. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt061.

Lujan ME, Jarrett BY, Brooks ED, Reines JK, Peppin AK, Muhn N, et al. Updated ultrasound criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: reliable thresholds for elevated follicle population and ovarian volume. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2013;28(5):1361–8. doi:10.1093/humrep/det062.

Robin G, Gallo C, Catteau-Jonard S, Lefebvre-Maunoury C, Pigny P, Duhamel A, et al. Polycystic Ovary-Like Abnormalities (PCO-L) in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):4236–43. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1836.

Piouka A, Farmakiotis D, Katsikis I, Macut D, Gerou S, Panidis D. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels reflect severity of PCOS but are negatively influenced by obesity: relationship with increased luteinizing hormone levels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(2):E238–43. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90684.2008.

Catteau-Jonard S, Bancquart J, Poncelet E, Lefebvre-Maunoury C, Robin G, Dewailly D. Polycystic ovaries at ultrasound: normal variant or silent polycystic ovary syndrome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(2):223–9. doi:10.1002/uog.11202.

Dewailly D, Pigny P, Soudan B, Catteau-Jonard S, Decanter C, Poncelet E, et al. Reconciling the definitions of polycystic ovary syndrome: the ovarian follicle number and serum anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations aggregate with the markers of hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4399–405. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0334.

Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome - Part 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(11):1291–300. doi:10.4158/ep15748.dsc.

Hart R, Doherty DA, Norman RJ, Franks S, Dickinson JE, Hickey M, et al. Serum antimullerian hormone (AMH) levels are elevated in adolescent girls with polycystic ovaries and the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Fertil Steril. 2010;94(3):1118–21. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.11.002.

Sopher AB, Grigoriev G, Laura D, Cameo T, Lerner JP, Chang RJ, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in nonobese adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;27(11-12):1175–9. doi:10.1515/jpem-2014-0128.

Pinola P, Morin-Papunen LC, Bloigu A, Puukka K, Ruokonen A, Jarvelin MR, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone: correlation with testosterone and oligo- or amenorrhoea in female adolescence in a population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2014;29(10):2317–25. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu182.

Mahran A, Abdelmeged A, El-Adawy AR, Eissa MK, Shaw RW, Amer SA. The predictive value of circulating anti-Mullerian hormone in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome receiving clomiphene citrate: a prospective observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(10):4170–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2193.

Knez J, Kovacic B, Medved M, Vlaisavljevic V. What is the value of anti-Mullerian hormone in predicting the response to ovarian stimulation with GnRH agonist and antagonist protocols? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):58. doi:10.1186/s12958-015-0049-5.

Broer SL, Dolleman M, van Disseldorp J, Broeze KA, Opmeer BC, Bossuyt PM, et al. Prediction of an excessive response in in vitro fertilization from patient characteristics and ovarian reserve tests and comparison in subgroups: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(2):420–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.024. e7.

Thessaloniki, ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2008;23(3):462–77. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem426.

Abu HH. Predictors of success of laparoscopic ovarian drilling in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an evidence-based approach. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(1):11–8. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3447-6.

Elmashad AI. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian drilling on anti-Mullerian hormone levels and ovarian stromal blood flow using three-dimensional power Doppler in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2342-6, 6 e1.. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.093.

Amer SA, Li TC, Ledger WL. The value of measuring anti-Mullerian hormone in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing laparoscopic ovarian diathermy. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2009;24(11):2760–6. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep271.

Mes-Krowinkel MG, Louwers YV, Mulders AG, de Jong FH, Fauser BC, Laven JS. Influence of oral contraceptives on anthropomorphometric, endocrine, and metabolic profiles of anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome patients. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(6):1757–65 e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.039.

Leelaphiwat S, Jongwutiwes T, Lertvikool S, Tabcharoen C, Sukprasert M, Rattanasiri S, et al. Comparison of desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol plus spironolactone versus cyproterone acetate/ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014. doi:10.1111/jog.12543.

Amsterdam, ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd Pcos Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on women's health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27(1):14–24. doi:10.1093/humrep/der396.

Panidis D, Georgopoulos NA, Piouka A, Katsikis I, Saltamavros AD, Decavalas G, et al. The impact of oral contraceptives and metformin on anti-Mullerian hormone serum levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and biochemical hyperandrogenemia. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(8):587–92. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.507283.

Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Norman RJ. The use of anti-mullerian hormone in predicting menstrual response after weight loss in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3796–802. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1188.

Nybacka A, Carlstrom K, Fabri F, Hellstrom PM, Hirschberg AL. Serum antimullerian hormone in response to dietary management and/or physical exercise in overweight/obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):1096–102. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.030.

Thomson RL, Buckley JD, Moran LJ, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Norman RJ, et al. The effect of weight loss on anti-Mullerian hormone levels in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and reproductive impairment. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2009;24(8):1976–81. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep101.

Nascimento AD, Silva Lara LA, Japur de Sa Rosa-e-Silva AC, Ferriani RA, Reis RM. Effects of metformin on serum insulin and anti-Mullerian hormone levels and on hyperandrogenism in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(3):246–9. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.736563.

Grigoryan O, Absatarova J, Andreeva E, Melnichenko G, Dedov I. Effect of metformin on the level of anti-Mullerian hormone in therapy of polycystic ovary syndrome in obese women. Minerva Ginecol. 2014;66(1):85–9.

Piltonen T, Morin-Papunen L, Koivunen R, Perheentupa A, Ruokonen A, Tapanainen JS. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels remain high until late reproductive age and decrease during metformin therapy in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2005;20(7):1820–6. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh850.

Madsen HN, Lauszus FF, Trolle B, Ingerslev HJ, Torring N. Impact of metformin on anti-Mullerian hormone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(5):547–51. doi:10.1111/aogs.12605.

Anderson RA, Anckaert E, Bosch E, Dewailly D, Dunlop CE, Fehr D, et al. Prospective study into the value of the automated Elecsys antimullerian hormone assay for the assessment of the ovarian growing follicle pool. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(4):1074–80 e4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.004.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Marcelle Cedars (University of California, San Francisco, USA) for assistance in language corrections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the study: AD. Revising the article critically for intellectual content: SCJ, GR, DD. Final approval of the version to be submitted: DD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Agathe Dumont is graduated in Medical Gynecology, from Lille University (2015, France). She is getting specialized in Reproductive Medicine and in Endocrine Gynecology. Her main fields of interest are Polycystic Ovaries, Anti Mullerian Hormone and Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dumont, A., Robin, G., Catteau-Jonard, S. et al. Role of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 13, 137 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0134-9