Abstract

Background

The application of side-to-end anastomosis (SEA) in sphincter-preserving resection (SPR) is controversial. We performed a meta-analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of SEA with colonic J-pouch (CJP) anastomosis, which had been proven effective in improving postoperative bowel function.

Methods

The protocol was registered in PROSPERO under number CRD42020206764. PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials databases were searched. The inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the safety or efficacy of SEA in comparison with CJP anastomosis. The outcomes included the pooled risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous variables and weighted mean differences (WMDs) for continuous variables. All outcomes were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) by STATA software (Stata 14, Stata Corporation, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 864 patients from 10 RCTs were included in the meta-analysis. Patients undergoing SEA had a higher defecation frequency at 12 months after SPR (WMD = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.14–0.26; P < 0.01) than those undergoing CJP anastomosis with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54) and a lower incidence of incomplete defecation at 3 months after surgery (RR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.09–0.86; P = 0.03). A shorter operating time (WMD = − 17.65; 95% CI, − 23.28 to − 12.02; P < 0.01) was also observed in the SEA group without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54). A higher anorectal resting pressure (WMD = 6.25; 95% CI, 0.17–12.32; P = 0.04) was found in the SEA group but the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 84.5%, P = 0.84). No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of efficacy outcomes including defecation frequency, the incidence of urgency, incomplete defecation, the use of pads, enema, medications, anorectal squeeze pressure and maximum rectal volume, or safety outcomes including operating time, blood loss, the use of protective stoma, postoperative complications, clinical outcomes, and oncological outcomes.

Conclusions

The present evidence suggests that SEA is an effective anastomotic strategy to achieve similar postoperative bowel function without increasing the risk of complications compared with CJP anastomosis. The advantages of SEA include a shorter operating time, a lower incidence of incomplete defecation at 3 months after surgery, and better sphincter function. However, close attention should be paid to the long-term defecation frequency after SPR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the progress of surgical techniques and multimodal treatment, an increasing number of patients agree to undergo sphincter-preserving resections (SPRs) [1]. SPR maintains bowel continuity, and the procedure avoids permanent stoma [2]. Some studies have indicated that SPR patients experienced a better quality of life and overall survival comparable to those undergoing abdominoperineal resections (APRs) [3, 4]. However, 80–90% of SPR patients have different degrees of anorectal disorders [5]. Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) includes disordered bowel function after rectal resection, leading to a detriment in quality of life, and it incorporates a vast array of anorectal disorders after sphincter-preserving surgery such as fecal incontinence, urgency, clustering, and evacuation problems [6]. LARS has greatly weakened the advantages of SPR, and patients prefer APR over SPR owing to severe LARS [7].

To overcome the adverse functional outcomes of traditional straight colorectal anastomosis (SCA), some modified rectal reconstructions have been proposed. Colonic J-pouch (CJP) anastomosis has been extensively studied since it was initially proposed in 1986 [8, 9]. In this procedure, the distal colon is closed and folded, and the bottom of the J-pouch is anastomosed with the residual rectum or anal canal. CJP anastomosis is considered an optimal method for rectal reconstruction with acceptable complications [10, 11]. More importantly, CJP anastomosis increases the volume of the reservoir and effectively improves the bowel function, but some evacuation problems may persist [12,13,14]. Nevertheless, CJP anastomosis cannot be utilized with a narrow pelvis, bulky anal sphincters, or insufficient colon length [15]. Side-to-end anastomosis (SEA) [16] has also been used to form even smaller reservoirs; therefore, SEA is theoretically supposed to combine the advantages of the CJP anastomosis, with a wider range of applications, lesser surgical complexity, and better evacuation [17].

Looking at the last five systematic reviews or meta-analyses of SEA and CJP anastomosis studies [18,19,20,21,22], Hüttner et al. [21] barely investigated surgical and oncological outcomes and they failed to analyze the source of high heterogeneity even though they analyzed six publications. Four other studies [18,19,20, 22] contained only four or fewer publications. In addition, none of the five studies was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO) or Cochrane. In the past 5 years, several RCTs have been published, and we performed an updated meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of SEA compared with CJP anastomosis. Additional anastomotic techniques, such as transverse coloplasty, have also been developed, but safety reasons and debated functional outcomes have prevented their widespread adoption. As a result, these methods of rectal reconstructions were not included in this meta-analysis.

This study was performed according to the Cochrane Collaboration methodology and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [23, 24] statement.

Methods

Protocol and registration

In accordance with established PRISMA (Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, the prospective protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42020206764), available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=206764 (Additional file 1).

Data sources and searches

We used medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text words to search PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials before June 21, 2020. The search strategy was developed with a professional trial search coordinator. The search items were as follows: rectal cancer, rectal neoplasms, rectal tumors, cancer of rectum, side-to-end, end-to-side, and Baker anastomosis. We also reviewed references cited in relevant articles and several conference abstracts, including those of the International Congress of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and the Scientific Session of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Details of the literature search are shown in Additional file 2.

Selection and exclusion criteria

Studies were selected on the basis of the Patient problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) criteria as follows:

-

1.

Population: patients with rectal cancer and treated by SPR

-

2.

Intervention: SEA

-

3.

Comparator: CJP anastomosis

-

4.

Efficiency outcome measures were as follows: (a) defecation frequency (times/day), (b) the number of patients with urgency, (c) the number of patients with incomplete defecation, (d) the number of patients using pads, and (e) the number of patients using enema and medication. In addition, anorectal manometry data were also extracted to evaluate anorectal function. The safety outcome measures were as follows: (a) the number of patients with perioperative complications, (b) the number of patients with reoperations (except stoma reversal), (c) the number of patients treated with protective stoma, (d) the number of patients with relapse (< 2 year), (e) mortality (in-hospital or 30 days after surgery), (f) postoperative hospital stay (days), (g) operating time (min), and (h) blood loss (ml).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) case reports, conference abstracts, and animal experiments; (2) reviews or meta-analyses; (3) case-control studies; and (4) original studies lacking available data.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two trained reviewers independently extracted the following data: study demographics and characteristics, including (1) first author, (2) publication year, (3) country, (4) multi-center status, (5) study duration, (6) the number of patients, (7) tumor level, and (8) tumor stage besides safety and efficacy outcomes. We used the estimated values based on the Cochrane Handbook when we could not obtain mean values and standard deviations (SDs) from the eligible studies [25, 26]. Disagreements were resolved to reach a consensus through discussion or consulting with a third investigator.

The methodological quality of RCTs was evaluated by the Jaded Scale for randomization procedures, the proportionality of the randomization method, blinding, the procedure of blinding, and statement and cause of withdrawals [27].

Statistical analysis

We estimated outcomes by calculating the pooled RR for dichotomous variables and WMD for continuous variables by STATA software (Stata 14, Stata Corporation, TX, USA). Fixed-effects or random-effects models were applied to compute the pooled effect size with 95% CI. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated using the I-squared statistics (I2), and I2 > 50% was considered high [28]. Sensitivity analyses, cumulative analyses, and subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the influence on the overall results and discover the source of heterogeneity. Moreover, funnel plots, Harbord’s test and Egger’s test were performed to assess the publication bias of the included studies [29, 30].

Results

Included studies

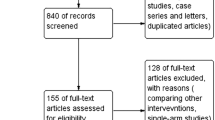

The results of the literature search identified 672 studies, and 10 RCTs [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (11 publications with 2 using the same cohort) were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Most of the studies were performed in Europe and Asia. The interventions of six studies [31,32,33,34, 36,37,38] were comparisons between SEA and CJP anastomosis, and the other four studies [35, 39,40,41] were based on three-arm trials. A total of 864 patients were available for this meta-analysis, and the characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Surgical details of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes

All the included studies provided data about bowel function except the study by Rasulov et al. [39]. Three studies [36, 37, 40] could not be evaluated in the analysis because the bowel function data were evaluated by the validated Colorectal Functional Outcome (COREFO) questionnaire’s summary score, the modified version of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) questionnaire, and composite evacuation/incontinence scores. The original data were not available even though we tried to contact the corresponding authors.

Bowel function

In the pooled analysis of all 5 trials [31, 32, 34, 35, 41], the combination of defecation frequency in the CJP group was less than that in the SEA group at 12 months after SPR (WMD = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.14–0.26; P < 0.01), and there was no statistically significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.84). Random-effect analyses showed a trend towards less frequency at 3 months, 6 months, and 24 months after surgery. However, no significant differences were noted and heterogeneities were high (Fig. 2).

Of the included studies, four studies [31, 34, 35, 38] reported urgency, three studies [32, 34, 38] reported the rate of using pads, four studies [31, 34, 35, 38] reported the incomplete defecation, and three studies [31, 32, 34] reported the number of patients using enemas or other medications at 6 months after surgery. The available data pooled from two studies [31, 34] showed that SEA had benefits in terms of completeness of defecation 3 months after surgery (RR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.09–0.86; P = 0.03). Other efficacy outcomes were not associated with the method of rectal reconstruction after SPR (Table 3).

Anorectal manometry

Four studies [31, 33,34,35] reported anorectal manometry data. However, meta-analysis could not be performed using all the studies. Huber et al. [31] and Akira et al. [35] reported their results with bar graphs, and the original data were not available. Pooled data from the other two studies [33, 34] that reported SEA were associated with high anorectal resting pressure (WMD = 6.25; 95% CI, 0.17–12.32; P = 0.04) but the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 84.5%, P = 0.01). We failed to find the source of heterogeneity due to the limitation of the included studies. Squeeze pressure and maximal tolerable volume were not associated with the method of rectal reconstruction after SPR (WMD = 23.83; 95% CI − 25.86 to 73.51; P = 0.35; WMD = − 20.37; 95% CI − 87.97 to 47.23; P = 0.56), and there was high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.5%, P < 0.001; I2 = 93.5%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The anorectal manometry details are available in Additional file 3.

Safety outcomes

Surgical outcomes

Pooled data from six studies [31, 32, 34, 38, 39, 41] reported operating times that showed no difference between SEA and CJP anastomosis (WMD = − 14.30; 95% CI, − 47.44 to 18.84; P = 0.40). When excluding one highly heterogeneous study [39] by the sensitivity analysis, SEA had a shorter operation time than CJP anastomosis (WMD = − 17.65; 95% CI, − 23.28 to − 12.02; P < 0.01) without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54) (Fig. 4).

Blood loss was not affected by the two different anastomotic approaches (WMD = − 11.7; 95% CI, − 32.64 to 9.24; P = 0.27). Similarly, there was no heterogeneity between the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.88) (Fig. 4).

All 10 RCTs [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] included protective stoma. However, the meta-analysis was performed including only seven RCTs [31,32,33,34,35,36, 39, 40] because the other three RCTs [37, 38, 41] showed that all patients were treated with protective stoma. No significant differences were observed among the groups (RR = − 1.09; 95% CI, 0.86–1.40; P = 0.47). However, the heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 53.2%, P < 0.05). The subgroup analysis revealed that the use of protective stoma was still comparable between SEA and CJP anastomosis in Europe (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.91–1.15; P = 0.69) and Asia (RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 0.43–5.26; P = 0.52) (Fig. 5). Sensitivity analysis and cumulative analysis revealed that the heterogeneity was caused by one study with the smallest sample size [35].

Clinical and oncological outcomes

No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of anastomotic leakage (RR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.41–1.13; P = 0.14), anastomotic stricture (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.29–3.30; P = 0.96), pouch-related complications (RR = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.13–2.30; P = 0.32), pelvic sepsis (RR = 1.77; 95% CI, 0.87–3.60; P = 0.11), intestinal obstruction (RR = 1.10; 95% CI, 0.53–2.24; P = 0.83), wound infection (RR = 1.18; 95% CI, 0.39–3.62; P = 0.77), rectovaginal fistula (RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.24–3.79; P = 0.94), urinary complication (RR = 0.72; 95% CI 0.31–1.69; P = 0.53), cardiovascular complications (RR = 1.55; 95% CI, 0.31–7.76; P = 0.62), pneumonia (RR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.16–3.85; P = 0.77), and postoperative hospital stay (WMD = 0.42; 95% CI, − 1.72 to 2.56; P = 0.70). Random model analysis revealed that oncological outcomes including in-hospital mortality, reoperation and relapse were not significantly different between the two rectal reconstructions with low heterogeneity (Table 4).

Cumulative meta-analyses, sensitivity analyses, and subgroup analyses

Cumulative meta-analyses, sensitivity analyses, and subgroup analyses (according to the geographical location or sample size) were implemented to investigate the heterogeneity of operating time; protective stoma use; defecation frequency in the 3rd, 6th, and 24th month; incomplete defecation in the 3rd and 6th month; and anorectal manometry. Studies by Akira et al. [35] and Rasulov et al. [39] were the main drivers of heterogeneity in this review. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis revealed that the inclusion of the Asian study [34, 35] and fewer than 60 patients affected the heterogeneity or stability of the variables.

Publication bias

We performed Harbord’s and Egger’s tests to assess the publication bias of the included studies. Funnel plots, Harbord’s test, and Egger’s tests demonstrated no evidence of publication bias (P > 0.05) (Additional file 4).

Discussion

The present study showed that compared to CJP anastomosis, SEA had a shorter operating time and a higher anorectal resting pressure but a higher incidence of frequency in the 12th month after surgery. No significant difference was observed in the rate of protective stoma use, perioperative complications, postoperative hospital stay, mortality, reoperations, relapse, urgency, incomplete defecation, pad use, enema, or medication between the two surgical approaches.

The operating time in SEA was shorter than that in CJP anastomosis; the possible reasons were as follows. First, functional results in patients with either a short side limb (3 cm) or a long limb (6 cm) in SEA showed no significant difference [42]. Surgeons do not need to pursue a tension-free anastomosis at the expense of time-consuming colonic mobilization. Second, side-to-side anastomosis of the distal colon is unnecessary in SEA. However, this procedure may increase the operating time of CJP anastomosis. Third, operating time may increase in some patients with a narrow pelvis who underwent CJP anastomosis [15, 43]. In contrast, narrow operating space was not a limitation for SEA.

The rates of protective stoma use for the two anastomotic methods were not significantly different in our meta-analysis. After the subgroups were divided according to geographical location, we found that heterogeneity did not exist in the European studies. One Asian study [35] was excluded after cumulative analysis and sensitivity analysis were performed. In this study, 88.7% (15/17) of patients in the SEA group were treated with protective stoma compared to 31.6% (6/19) of patients in the CJP group. The small sample size may be related to the difference between groups. The pooled data of the remaining studies revealed that the rate of protective stoma use was independent of anastomotic methods. Impaired anorectal function was the main overall reason for a permanent stoma [44]. Okkabaz et al. [38] found that stoma closure could not be achieved in 28.1% of patients, with 11 (37.9%) in the CJP group and 5 (17.9%) in the SEA groups (P = 0.092). Although the difference was not statistically significant, more high-quality clinical trials are needed to determine whether CJP anastomosis is a risk factor for permanent stoma use.

The defecation frequency has not been previously analyzed quantitatively in published meta-analyses. Machado et al. [38], Jiang et al., and Okkabaz et al. [38] reported no significant difference in stool frequency between the CJP and SEA groups. However, in this study, SEA was associated with more bowel movements with low heterogeneity at the 12th month after SPR. The mechanism by which CJP anastomosis reduces defecation frequency has not yet been thoroughly studied. In 1999, Marco et al. [45] conducted an experimental study in the pig model. The difference of median neorectal compliance between small CJP anastomosis and SEA was significant (17.8 ml/mmHg vs 11.8 ml/mmHg, P < 0.001). Increased rectal compliance may contribute to fecal retention by decreasing the frequency [46].

Postoperative incomplete evacuation was more frequent in the J-pouch group than in the SEA group [31, 34], which was supported by a previous animal experiment [45]. The median times required for complete evacuation were 14 min and 4 min for CJP anastomosis and SEA, respectively. In our meta-analysis, SEA had no advantages over CJP in terms of evacuation. However, the few included studies and high heterogeneity made the evidence limited.

Suggested explanations for LARS include impaired neorectal capacity, decreased compliance, and the loss of rectal sensation [33, 47, 48], which could be evaluated by anorectal manometry. Anal resting and squeeze pressures help determine the presence of internal and external anal sphincter dysfunction [49]. Abnormally low resting pressure and no relaxation during rectal distension generally indicated that patients have severe weakness of the anal sphincter [47]. Our study showed that CJP anastomosis was associated with lower anorectal resting pressure and worse function of the anal sphincter. However, our evidence is insufficient because only two articles are included and the source of heterogeneity could not be analyzed.

In this meta-analysis, there was no heterogeneity for the majority of the safety and efficacy outcomes. We also tried to explain the potential sources of heterogeneity. Therefore, the pooled results were stable and conclusive.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was not possible to obtain data for several key comparisons, such as the incidence of diarrhea, constipation, and incontinence. Other functional outcomes such as defecate at night, fragmentation, and differentiation between flatus and feces were reported in only one particular publication, thereby preventing a meta-analysis. Long-term outcomes such as overall survival and disease-free survival and sexual and bladder function, which are closely related to the quality of life of rectal cancer patients were not studied in this meta-analysis. Second, the analysis of anorectal manometry and incomplete defecation contained only two or three publications. Even though each trial had various strategies and different patient characteristics, the heterogeneity cannot be discussed further. Third, the current findings were based mainly on single-center small sample studies. Considering the limited quality of evidence for most outcomes, the use of SEA might be recommended as an alternative under some circumstances. Finally, we await long-term data from several ongoing studies to contribute to a more robust analysis of long-term quality of life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current evidence suggests that SEA may be an effective strategy to expedite the surgical process without increasing the risks of surgery in SPR. Postoperative bowel functions of SEA were comparable to those of CJP anastomosis. However, close attention should be paid to the potential risk of frequent defecation. Because the present findings were based mainly on single-center studies, further powered studies are required to assess the implementation of this anastomotic technique.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SEA:

-

Side-to-end anastomosis

- SPR:

-

Sphincter-preserving resection

- CJP:

-

Colonic J-pouch

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean differences

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- APRs:

-

Abdominoperineal resections

- LARS:

-

Low anterior resection syndrome

- SCA:

-

Straight colorectal anastomosis

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Review

- COREFO:

-

Colorectal Functional Outcome

- MSKCC:

-

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

References

Nocera F, Angehrn F, von Flüe M, Steinemann DC. Optimising functional outcomes in rectal cancer surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;406:233–50.

Fernández-Martínez D, Rodríguez-Infante A, Otero-Díez JL, Baldonedo-Cernuda RF, Mosteiro-Díaz MP, García-Flórez LJ. Is my life going to change?-a review of quality of life after rectal resection. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11(1):91–101. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2019.10.03.

Du P, Wang SY, Zheng PF, Mao J, Hu H, Cheng ZB. Comparison of overall survival and quality of life between patients undergoing anal reconstruction and patients undergoing traditional lower abdominal stoma after radical resection. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(10):1390–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02106-x.

Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Eckel R, Sauer H, Hölzel D. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients: a four-year prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):203–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000080823.38569.b0.

Nguyen TH, Chokshi RV. Low anterior resection syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-020-00785-z.

Keane C, Fearnhead NS, Bordeianou LG, Christensen P, Espin Basany E, Laurberg S, et al. International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(3):300–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.15421.

Lee L, Trepanier M, Renaud J, Liberman S, Charlebois P, Stein B, et al. Patients’ preferences for sphincter preservation versus abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer. Surgery. 2021;169(3):623–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.020.

Lazorthes F, Fages P, Chiotasso P, Lemozy J, Bloom E. Resection of the rectum with construction of a colonic reservoir and colo-anal anastomosis for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1986;73(2):136–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800730222.

Parc R, Tiret E, Frileux P, Moszkowski E, Loygue J. Resection and colo-anal anastomosis with colonic reservoir for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1986;73(2):139–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800730223.

Dehni N, Parc R, Church JM. Colonic J-pouch-anal anastomosis for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(5):667–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-6629-7.

Brown S, Margolin DA, Altom LK, Green H, Beck DE, Kann BR, et al. Morbidity following coloanal anastomosis: a comparison of colonic J-pouch vs straight anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(2):156–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000960.

Liang JT, Lai HS, Lee PH, Huang KC. Comparison of functional and surgical outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted colonic J-pouch versus straight reconstruction after total mesorectal excision for lower rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(7):1972–9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9355-2.

Hallböök O, Påhlman L, Krog M, Wexner SD, Sjödahl R. Randomized comparison of straight and colonic J pouch anastomosis after low anterior resection. Ann Surg. 1996;224(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199607000-00009.

Paty PB, Cohen AM. Sphincter preservation in rectal cancer. Technical considerations for coloanal anastomosis and J-pouch. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1998;8(1):48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4296(98)80037-4.

Harris GJ, Lavery IJ, Fazio VW. Reasons for failure to construct the colonic J-pouch. What can be done to improve the size of the neorectal reservoir should it occur? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(10):1304–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-6414-7.

Baker JW. Low end to side rectosigmoidal anastomosis; description of technic. Arch Surg. 1950;61(1):143–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1950.01250020146016.

Zhang YC, Jin XD, Zhang YT, Wang ZQ. Better functional outcome provided by short-armed sigmoid colon-rectal side-to-end anastomosis after laparoscopic low anterior resection: a match-paired retrospective study from China. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(4):535–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1359-5.

Brown CJ, Fenech DS, McLeod RS. Reconstructive techniques after rectal resection for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:Cd006040.

Ooi BS, Lai JH. Colonic J-Pouch, Coloplasty, Side-to-end anastomosis: meta-analysis and comparison of outcomes. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;20(2):69–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.scrs.2009.05.004.

Siddiqui MR, Sajid MS, Woods WG, Cheek E, Baig MK. A meta-analysis comparing side to end with colonic J-pouch formation after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14(2):113–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0576-1.

Hüttner FJ, Tenckhoff S, Jensen K, Uhlmann L, Kulu Y, Büchler MW, et al. Meta-analysis of reconstruction techniques after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102(7):735–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9782.

Si C, Zhang Y, Sun P. Colonic J-pouch versus Baker type for rectal reconstruction after anterior resection of rectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(12):1428–35. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2013.845905.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25(20):3443–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2380.

Huber FT, Herter B, Siewert JR. Colonic pouch vs. side-to-end anastomosis in low anterior resection. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1999;42(7):896–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02237098.

Machado M, Nygren J, Goldman S, Ljungqvist O. Similar outcome after colonic pouch and side-to-end anastomosis in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):214–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000080824.10891.e1.

Machado M, Nygren J, Goldman S, Ljungqvist O. Functional and physiologic assessment of the colonic reservoir or side-to-end anastomosis after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a two-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0772-z.

Jiang JK, Yang SH, Lin JK. Transabdominal anastomosis after low anterior resection: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing long-term results between side-to-end anastomosis and colonic J-pouch. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(11):2100–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0139-0.

Tsunoda A. Side-to-end vs. colonic pouch vs. end-to-end anastomosis in low anterior resection. Showa Univ J Med Sci. 2008;20:61–8.

Doeksen A, Bakx R, Vincent A, van Tets WF, Sprangers MA, Gerhards MF, et al. J-pouch vs side-to-end coloanal anastomosis after preoperative radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a multicentre randomized trial. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(6):705–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02725.x.

Marković V, Dimitrijević I, Barišić G, Krivokapić Z. Comparison of functional outcome of colonic J-pouch and latero-terminal anastomosis in low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2015;143(3-4):158–61. https://doi.org/10.2298/SARH1504158M.

Okkabaz N, Haksal M, Atici AE, Altuntas YE, Gundogan E, Gezen FC, et al. J-pouch vs. side-to-end anastomosis after hand-assisted laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective randomized trial on short and long term outcomes including life quality and functional results. Int J Surg. 2017;47:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.09.012.

Rasulov AO, Baytchorov AB, Kuzmitchev DV, Merzlikina AM, Rakhimov OA, Ivanov VA, et al. Short-term results of rectum reconstruction after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Endoskopicheskaya khirurgiya. 2018;24(2):13–20. https://doi.org/10.17116/endoskop201824213.

Marti WR, Curti G, Wehrli H, Grieder F, Graf M, Gloor B, et al. Clinical outcome after rectal replacement with side-to-end, colon-J-pouch, or straight colorectal anastomosis following total mesorectal excision: a Swiss prospective, randomized, multicenter trial (SAKK 40/04). Ann Surg. 2019;269(5):827–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003057.

Parc Y, Ruppert R, Fuerst A, Golcher H, Zutshi M, Hull T, et al. Better function with a colonic J-pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis?: a randomized controlled trial to compare the complications, functional outcome, and quality of life in patients with low rectal cancer after a J-pouch or a side-to-end anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(5):815–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003249.

Tsunoda A, Kamiyama G, Narita K, Watanabe M, Nakao K, Kusano M. Prospective randomized trial for determination of optimum size of side limb in low anterior resection with side-to-end anastomosis for rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(9):1572–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a909d4.

Mantyh CR, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Coloplasty in low colorectal anastomosis: manometric and functional comparison with straight and colonic J-pouch anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(1):37–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02234818.

Gadan S, Floodeen H, Lindgren R, Rutegård M, Matthiessen P. What is the risk of permanent stoma beyond five years after low anterior resection for rectal cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(12):2098–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15364.

Sailer M, Debus ES, Fuchs KH, Fein M, Beyerlein J, Thiede A. Comparison of different J-pouches vs. straight and side-to-end coloanal anastomoses - experimental study in pigs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(5):590–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02234131.

Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1510–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064.

Sun WM, Donnelly TC, Read NW. Utility of a combined test of anorectal manometry, electromyography, and sensation in determining the mechanism of ‘idiopathic’ faecal incontinence. Gut. 1992;33(6):807–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.33.6.807.

Hallbk O, Nystrm P-O, Sjdahl R. Physiologic characteristics of straight and colonic J-pouch anastomoses after rectal excision for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(3):332–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02050425.

Jiang AC, Panara A, Yan Y, Rao SSC. Assessing anorectal function in constipation and fecal incontinence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):589–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2020.04.011.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

National Natural and Science Foundation of China (NNSFC): 81871962

National Key Research and Development Program of China: 2145000042

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY designed the research and revised the draft. SH, SZ, and FL were the main investigators and data recorders; they analyzed and interpreted the data. PG and QW revised and corrected the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The formal ethical review was waived by our institutional review board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

Registration of the protocol in PROSPERO.

Additional file 2:.

Details of the literature search.

Additional file 3:.

Details of anorectal manometry.

Additional file 4:.

Publication bias assessment. a. Funnel plots of publication bias. b. Harbord test of publication bias. c. Egger test of publication bias.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, S., Wang, Q., Zhao, S. et al. Safety and efficacy of side-to-end anastomosis versus colonic J-pouch anastomosis in sphincter-preserving resections: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg Onc 19, 130 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02243-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02243-0