Abstract

Background

Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) are underreported. The aim of this study is to describe clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes for patients with this rare tumor to raise awareness among clinicians and surgeons.

Methods

Retrospective review of records of a tertiary referral center and specialized liver unit was performed. Out of 3623 patients who underwent liver resection, 366 patients received surgical treatment for HCC; of them, eight (2.2%) had FL-HCC and were resected between October 2001 and December 2018.

Results

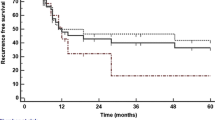

Eight patients (3 males and 5 females) with FL-HCC (median age 26 years) underwent primary surgical treatment. All patients presented with unspecific symptoms or were diagnosed as incidental finding. No patient had cirrhosis or other underlying liver diseases. Coincidentally, three patients (37.5%) had a thromboembolic event prior to admission. The majority of patients had BCLC stage C and UICC stage IIIB/IVA; four patients (50%) presented with lymph node metastases. The median follow-up period was 33.5 months. The 1-year survival was 71.4%, and 3-year survival was 57.1%. Median survival was at 36.4 months. Five patients (62.5%) developed recurrent disease after a median disease-free survival of 9 months. Two patients (25.0%) received re-resection.

Conclusion

FL-HCC is a rare differential diagnosis of liver masses in young patients. Since the prognosis is limited, patients with incidental liver tumors or lesions with suspicious features in an otherwise healthy liver should be presented at a specialized hepatobiliary unit. Thromboembolism might be an early paraneoplastic symptom and needs to be elucidated further in the context of FL-HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malignant primary liver tumors are rare in young adults. However, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FL-HCC) is an underestimated differential diagnosis of liver masses in young patients that can often be misinterpreted as benign lesions on radiological imaging and requires histopathological confirmation. FL-HCC was first described in 1956 [1] as a subtype of HCC. It has a low incidence (0.02 per 100,000) [2] and comprises between 1 and 9% of all HCC diagnoses [2,3,4]. The available data shows a minor male predominance (male to female case ratio 1.7:1) [2].

FL-HCC does not have specific symptoms and often presents as an incidental finding [5, 6]. In contrast to conventional HCC, it is not associated with cirrhosis, hepatitis, or other liver diseases [7, 8]. Unlike hepatic adenoma, FL-HCC has not been linked to estrogen or other hormones. Due to some radiomorphological similarities with focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) (both may present with a stellate central scar), FL-HCC can be misinterpreted as FNH [9]. A non-negligible portion of patients presents with advanced disease of FL-HCC, but their medical history reports show prior surveillance for FNH. Typically, they are referred to tertiary centers after the growth behavior of the lesion changed or intra-hepatic metastases have occurred. FNH has been reported as a synchronous or metachronous lesion in patients with FL-HCC [10,11,12,13,14]. It was initially suspected as a potential precursor lesion [9, 14, 15], but causality could not be proven [16, 17]. Until proven to be a benign lesion by biopsy, every FNH with uncommon radiological characteristics such as calcifications surrounded by hypervascular features [18, 19] should be considered a potential FL-HCC. On histological evaluation, vascular invasion is often present and up to 40% of patients have already developed regional lymph node metastasis [20, 21]. Most patients are in an advanced TNM stage at the time of diagnosis [20]. Genetically, FL-HCC is defined by a focal deletion leading to DNAJB1-PRKACA gene, which can be reliably detected in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue and is pathognomonic for FL-HCC [17, 22,23,24]. Immunostaining typically reveals coexpression of CD68 (KP-1 clone) and CK7 [17].

A more favorable prognosis for FL-HCC compared to classic HCC was discussed after partial hepatectomy. The 5-year survival rates in surgical reports range from 70 to 76% [4, 25] with a median overall survival between 84 and 112 months [25, 26]. In contrast, non-resectable FL-HCC showed a dismal prognosis with 5-year survival of 0% and overall median survival of 12 months [26, 27]. However, even after resection, aggressive behavior with early relapse (median time to recurrence 10–33 months [27]) and recurrence rates between 33 and 100% have been reported [4]. This underlines the absolute necessity for early detection to allow potentially curative treatment in specialized hepatobiliary units. The aim of this study was to describe clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes for patients with this rare tumor to raise awareness among clinicians and surgeons.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty Heidelberg at Ruprecht Karls University in Heidelberg and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments [28]. A retrospective analysis of patients referred to the Department of General, Visceral and Transplantation Surgery of Ruprecht Karls University for liver surgery between October 2001 and December 2018 was performed. A total of 3623 patients underwent liver resection for various conditions during this period. A total of 366 patients received a liver resection due to HCC, and of these, eight patients underwent an exploration due to FL-HCC, seven received a liver resection with primary curative intention, and one patient had an extensively metastasized intraoperative finding, rendering curative resection unattainable.

Prior to operation, each patient received a standard clinical work-up, including thorax and abdominal imaging (contrast-enhanced CT and/or MRI with liver-specific contrast agent), laboratory work-up, and clinical assessment. Clinicopathological features are shown in Table 1.

Morbidity and mortality of the surgical procedure as well as recurrence rate and survival were analyzed as outcome parameters.

None of the patients presented with synchronous malignancies. All patients received primarily surgical treatment, and no preoperative radiological intervention (preoperative portal or hepatic vein embolization or neoadjuvant treatment) was administered. All patients received a postoperative consultation by an oncologist with recommendation in accordance with the actual recommendation.

Anatomic disease extent was described using the pTNM classification developed by Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and clinical stage was described according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification. Liver resections are defined according to the Brisbane 2000 Terminology of liver anatomy and resections.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables; medians and range are reported. Frequency distribution described categorical variables. Mortality is defined as death occurring in the hospital or within 30 days after surgery. Due to the small sample size, analysis is limited to descriptive statistics.

Results

Retrospective analysis identified eight patients with FL-HCC, who underwent exploration with curative intent within a 17-year period (October 2001to December 2018). Five female and three male patients with a median age of 26 years (range 18–36 years) received surgery.

Three patients had a liver mass as incidental finding on imaging prompted by unrelated conditions: one patient received abdominal MRI after an X-ray performed for shoulder pain complaint showed elevated diaphragm on the right side, one patient received abdominal ultrasound after presenting at the hospital with DVT, and one patient received a CT scan of the thorax due to pneumonia, which revealed a mass in the observable section of the liver. Four patients had vague abdominal discomfort that led to imaging and diagnosis.

All patients presented with the absence of liver disease, and no cirrhosis was found on pathology examinations of the non-tumor tissue.

AFP was slightly elevated (> 8 IU/ml) in two patients (25.0%); however, no patient had an elevation above 15 IU/ml. Preoperative laboratory findings were unremarkable in all patients and showed no liver dysfunction. Pathological findings are presented in Table 2. 62.5% presented with BCLC stage C, and the rest (37.5%) had stage A.

Median time between diagnosis through biopsy or imaging and surgery was 21 days with a range of 7 to 240 days.

Incidentally, three patients (37.5%) had a thromboembolic event prior to admission. Otherwise, no patient presented with major preoperative morbidity, such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic diseases.

Imaging showed well-circumscribed lesions with a central scar, and most showed an arterial hyperenhancement. Figure 1 exemplifies findings in the current group.

MRI scan of a 17-year-old female patient. a) Axial T2 weighted Half-Fourier Acquisition Single-shot Turbo spin Echo (HASTE) sequence shows a large inhomogenous hepatic lesion with a central moderately T2-hyperintense scar (white arrowheads) in the left lateral and medial as well as right anterior sectors. b) The central scar (white arrowheads) is more prominent in the axial native T1 Fast Low-Angle Shot (Flash) 2D sequence. c) The lesion shows markedly inhomogenous hyperenhancement in the arterial phase (axial T1 FLASH 3D). The central scar (white arrowheads) does not enhance. d) A ventral part of the lesion shows washout appearance (black arrows) in the portal venous phase (axial T1 FLASH 3D).

Seven patients (85.7%) who underwent curative treatment presented with a single lesion, and one patient had multiple (12.5%).

Three patients (37.5%) received major resections, and four (50.0%) were treated with minor resection (typical or atypical resection of three segments or less). One patient scheduled for curative surgery showed prior undiagnosed extensive peritoneal metastasis at exploration and received an open biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis.

There was no in-house or 90-day mortality among this group of patients. Postoperative morbidity rate was 25% for major complications (≥ Clavien-Dindo grade 3) and involved two patients. One patient developed multiple complications: a bile leak (grade C), early postoperative portal vein thrombosis, hematothorax, and ARDS; one patient had a wound dehiscence requiring repeated surgery.

One patient underwent resection at our center due to recurrence after being surgically treated with a right hemihepatectomy 2 years prior at another hospital, after which the patient was monitored for recurrence.

Median follow-up was 47 months (range 1 to 60 months). The recurrence rate after hepatectomy was 71.4 % (intrahepatic: n = 3, diffuse: n = 2). Five patients (62.5%) received treatment for progressive disease: either as chemotherapy alone or in combination with radiation or local radiological therapies as an individual approach. Three patients have died during follow-up. The 1-year survival was 71.4%, and 3-year survival was 57.1%, with a median survival time of 36.5 months after resection. Follow-up is summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

After FL-HCC was first described by Edmondson in 1956, little progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of this entity. Especially in the European region, there are only limited reports available, thus making even an estimation of incidence for the region difficult. Most reports are limited to case descriptions. In the USA, FL-HCC estimates less than 1% of all primary liver tumors according to the SEER database [3]; in contrast, Mexico reported an incidence rate of 5.8% [29]. Table 4 provides an overview of the reports on clinicopathological features and treatments of FL-HCC from the European region published in the last 10 years.

FL-HCC predominantly affects younger patients, ages 10–30 years old, although a second incidence peak has been described at ages 60–69 [2]. The current series consisted of patients all aged below 36 years all presented with pure FL-HCC. It is conceivable and should be evaluated further, if patients falling into the second incidence peak have a fibrolamellar-like, conventional HCC. A systematic testing for a DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion gene is needed to assess this.

The slight male predominance reported in the analysis of the SEER database [2] is consistent with the current dataset. Most patients either present with incidental findings or undergo work-up for abdominal pain and weight loss [30], and the current dataset reports consistent findings.

Three patients had a history of deep venous thrombosis, with one showing acute signs, due to extensive phlebothrombosis, spreading to the inferior vena cava. Although venous thromboembolism is associated with a number of cancers [31], it is not commonly described for HCC, especially rare HCC subtypes. There is an established association between cirrhosis and venous thromboembolism [32, 33], but cirrhosis in FL-HCC patients is uncommon. A link between thrombocytosis as paraneoplastic syndrome of HCC due to TPO-overproduction and large tumor volume, as well as high alpha-fetoprotein, has previously been described by Hwang et al. [34]. Two patients with history of deep venous thrombosis also had thrombocytosis on admission in the current cohort, and all three had large tumor volume, although alpha-fetoprotein was fairly low (< 13.5 IU/ml) in all patients. Only few reports describe an association between FL-HCC and thrombosis, such as atrial thrombus and pulmonary emboli [35] and thrombus in the main portal vein [36]. A large-scale study is needed to further investigate the association of thrombocytosis or thromboembolic events and FL-HCC.

Other paraneoplastic symptoms have previously been described in case reports for FL-HCC. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy [37,38,39] is the most prevalent symptom described in the literature. Several pathophysiological pathways need to be evaluated in these cases, such as hepatocellular dysfunction, portosystemic shunting, and ornithine transcarbamylase mutation. However, in most reported cases, none of these mechanisms sufficiently explains the degree of hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Table 5 provides an overview of reports describing FL-HCC presenting with potential paraneoplastic symptoms. Interestingly, the association between FL-HCC and gynecomastia has only been described in pediatric population.

Vascular invasion was present in six patients: one proved to be unresectable, while five received surgery with curative intent. Four of these patients developed a recurrence. Three patients had positive lymph nodes, two of which developed a recurrence. Vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis have been described in association with a worse outcome after surgical treatment of FL-HCC [40, 41]. The current study supports previously described association.

As with most cancers, negative resection margins are associated with a better outcome [41]. In the current dataset, five of seven successfully resected patients had negative resection margins, while two remaining had microscopically positive resection margins. Four R0 resected patients showed a recurrence, and one patient with R1 situation had a recurrence within 3 months. Despite R0 resection margins, some series report a high recurrence rate of up to 71% for FL-HCC [42]. Interestingly, four out of five R0 resected patients showed longer survival (median survival 53 months, range 7–60 months) compared to R1 resected patients, despite most presenting with a recurrence after surgery.

Female gender has been previously described as a variable associated with a better overall survival [42]; however, other reports contradict this finding [5]. Interestingly, both patients in the current dataset who died during follow-up were female.

Surgery remains the mainstream treatment for FL-HCC; however, chemotherapy does not offer potential benefit in unresectable patients. Most patients receive sorafenib in unresectable cases with unsatisfactory results. Some publications report a stable disease under this regimen [42], while others reported progression [43]. Few case reports explore non-standard treatment options with varying reports. Mafeld et al. reported a case of FL-HCC successfully treated with TACE and subsequent SIRT using Yttrium-90 leading to tumor downsize to a resectable size [44]. Benito et al. reported usage of adjuvant sunitinib after the resection of FL-HCC with metastasis to the ovary with recurrence-free patient at 12 months [45]. Doubtless, studies of chemotherapies in unresectable patients are necessary in the future.

Conclusion

The clinicopathological features and outcomes described in this report are consistent with those published in the literature. Further reports from the European region are necessary to evaluate FL-HCC further in this part of the world. Since deep venous thrombosis is not usually present in young, otherwise healthy individuals, with no liver cirrhosis, findings in this report are thought-provoking and the association between FL-HCC and vascular thromboembolism should be studied on a larger scale. Further, more reports on adjuvant or palliative treatment of FL-HCC may shed light on chemotherapy regimens with most beneficial clinical outcomes.

Due to limited data on FL-HCC, low incidence affecting predominantly young patients without comorbidities and oftentimes vascular invasion at the time of diagnosis, clinicians should be vigilant. It is imperative to promptly refer patients with incidental liver masses to a hospital with a specialized hepatobiliary surgery unit for evaluation and surgical treatment. Due to a similar radiological presentation of FL-HCC and FNH, all patients presenting with atypical FNH on imaging should be evaluated at a tertiary referral center to avoid fatal outcome due to misdiagnosis.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- DVT:

-

Deep venous thrombosis

- FL-HCC:

-

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

- FNH:

-

Focal nodular hyperplasia

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- SIRT:

-

Selective internal radiation therapy

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TAE:

-

Transarterial embolization

- UICC:

-

Union for International Cancer Control

References

Edmondson HA. Differential diagnosis of tumors and tumor-like lesions of liver in infancy and childhood. AMA J Dis Child. 1956;91(2):168–86.

Eggert T, McGlynn KA, Duffy A, Manns MP, Greten TF, Altekruse SF. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA, 2000-2010: a detailed report on frequency, treatment and outcome based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1(5):351–7.

El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? A US population-based study. Hepatology. 2004;39(3):798–803.

Mavros MN, Mayo SC, Hyder O, Pawlik TM. A systematic review: treatment and prognosis of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(6):820–30.

Ang CS, Kelley RK, Choti MA, Cosgrove DP, Chou JF, Klimstra D, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma: data from the fibrolamellar carcinoma consortium. Gastrointestinal cancer research : GCR. 2013;6(1):3–9.

Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmondson HA, Omata M. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: a tumor of adolescents and young adults with distinctive clinico-pathologic features. Cancer. 1980;46(2):372–9.

Hodgson HJ. Fibrolamellar cancer of the liver. J Hepatol. 1987;5(2):241–7.

Berman MA, Burnham JA, Sheahan DG. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: an immunohistochemical study of nineteen cases and a review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1988;19(7):784–94.

Palm V, Sheng R, Mayer P, Weiss KH, Springfeld C, Mehrabi A, et al. Imaging features of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI. Cancer Imaging. 2018;18(1):9.

Farhi DC, Shikes RH, Silverberg SG. Ultrastructure of fibrolamellar oncocytic hepatoma. Cancer. 1982;50(4):702–9.

Imkie M, Myers SA, Li Y, Fan F, Bennett TL, Forster J, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma arising in a background of focal nodular hyperplasia: a report of 2 cases. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(8):633–7.

Saul SH, Titelbaum DS, Gansler TS, Varello M, Burke DR, Atkinson BF, et al. The fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma. Its association with focal nodular hyperplasia. Cancer. 1987;60(12):3049–55.

Saxena R, Humphreys S, Williams R, Portmann B. Nodular hyperplasia surrounding fibrolamellar carcinoma: a zone of arterialized liver parenchyma. Histopathology. 1994;25(3):275–8.

Vecchio FM, Fabiano A, Ghirlanda G, Manna R, Massi G. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: the malignant counterpart of focal nodular hyperplasia with oncocytic change. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1984;81(4):521–6.

Berman MM, Libbey NP, Foster JH. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Polygonal cell type with fibrous stroma--an atypical variant with a favorable prognosis. Cancer. 1980;46(6):1448–55.

Torbenson M. Review of the clinicopathologic features of fibrolamellar carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14(3):217–23.

Torbenson MS. Morphologic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2017;46(2):365–91.

Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, Madariaga J, Nalesnik M, Marsh W. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: imaging and pathologic findings in 31 recent cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):352–61.

Friedman AC, Lichtenstein JE, Goodman Z, Fishman EK, Siegelman SS, Dachman AH. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 1985;157(3):583–7.

Chaudhari VA, Khobragade K, Bhandare M, Shrikhande SV. Management of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2018;7(5):51.

Pinna AD, Iwatsuki S, Lee RG, Todo S, Madariaga JR, Marsh JW, et al. Treatment of fibrolamellar hepatoma with subtotal hepatectomy or transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;26(4):877–83.

El Jabbour T, Lagana SM, Lee H. Update on hepatocellular carcinoma: pathologists’ review. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(14):1653–65.

Graham RP, Jin L, Knutson DL, Kloft-Nelson SM, Greipp PT, Waldburger N, et al. DNAJB1-PRKACA is specific for fibrolamellar carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(6):822–9.

Honeyman JN, Simon EP, Robine N, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Darcy DG, Lim II, et al. Detection of a recurrent DNAJB1-PRKACA chimeric transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2014;343(6174):1010–4.

Stipa F, Yoon SS, Liau KH, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, et al. Outcome of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1331–8.

Njei B, Konjeti VR, Ditah I. Prognosis of patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma versus conventional hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2014;7(2):49–54.

Torbenson M. Fibrolamellar carcinoma: 2012 update. Scientifica (Cairo). 2012;2012:743790.

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama. 2013;310(20):2191-4.

Arista-Nasr J, Gutierrez-Villalobos L, Nuncio J, Maldonaldo H, Bornstein-Quevedo L. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in mexican patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2002;8(2):133–7.

Malouf GG, Brugieres L, Le Deley MC, Faivre S, Fabre M, Paradis V, et al. Pure and mixed fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas differ in natural history and prognosis after complete surgical resection. Cancer. 2012;118(20):4981–90.

Abdol Razak NB, Jones G, Bhandari M, Berndt MC, Metharom P. Cancer-associated thrombosis: an overview of mechanisms, risk factors, and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(10):380.

Bikdeli B, Jimenez D, Garcia-Tsao G, Barba R, Font C, Diaz-Pedroche MDC, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with liver cirrhosis: findings from the RIETE (Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbolica) registry. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45(8):793–801.

Wu H, Nguyen GC. Liver cirrhosis is associated with venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients in a nationwide US study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(9):800–5.

Hwang SJ, Luo JC, Li CP, Chu CW, Wu JC, Lai CR, et al. Thrombocytosis: a paraneoplastic syndrome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(17):2472–7.

Asrani SK, LaRusso NF. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with Budd-Chiari syndrome, right atrial thrombus, and pulmonary emboli. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):977–8.

Bhagat M, Kembhavi S, Qureshi SS. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with extensive vascular thrombosis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(2):493–4.

Cho J, Chen JCY, Paludo J, Conboy EE, Lanpher BC, Alberts SR, et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy in a patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: case report and literature review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(3):582–8.

Surjan RC, Dos Santos ES, Basseres T, Makdissi FF, Machado MA. A proposed physiopathological pathway to hyperammonemic encephalopathy in a non-cirrhotic patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma without ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) mutation. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:234–41.

Thakral N, Simonetto DA. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: an unusual presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2019.

Chagas AL, Kikuchi L, Herman P, Alencar RSSM, Tani CM, Diniz MA, et al. Clinical and pathological evaluation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center study of 21 cases. Clinics. 2015;70:207–13.

Darcy DG, Malek MM, Kobos R, Klimstra DS, DeMatteo R, La Quaglia MP. Prognostic factors in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in young people. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(1):153–6.

Chakrabarti S, Tella SH, Kommalapati A, Huffman BM, Yadav S, Riaz IB, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(3):554–61.

Ang CS, Kelley RK, Choti MA, Cosgrove DP, Chou JF, Klimstra D, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma: data from the fibrolamellar carcinoma consortium. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6(1):3–9.

Mafeld S, French J, Tiniakos D, Haugk B, Manas D, Littler P. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with yttrium-90 and subsequent surgical resection. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(5):816–20.

Benito V, Segura J, Martinez MS, Arencibia O, Lubrano A. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the ovary. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(2):200–2.

Ince V, Isik B, Ozdemir F, Ozgor D, Ara C, Yilmaz S. Living-donor liver transplant for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with hilar lymph node metastasis: a case report. Exp Clin Transplant. 2018.

Bill R, Montani M, Blum B, Dufour JF, Escher R, Buhlmann M. Favorable response to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in a young patient with unresectable fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver. Hepatology. 2018;68(1):384–6.

Ciurea SH, Matei E, Stanescu CS, Lupescu IG, Boros M, Herlea V, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with ovarian metastasis - an unusual presentation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58(1):187–92.

Estrella Diez E, Alvarez Higueras FJ, Marin Zafra G, Bas Bernal A, Garre Sanchez C, Egea Valenzuela J, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a rare entity diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108(8):494–5.

Bauer U, Mogler C, Braren RF, Algul H, Schmid RM, Ehmer U. Progression after immunotherapy for fibrolamellar carcinoma. Visc Med. 2019;35(1):39–42.

Bender HU, Staudigl M, Schmid I, Fuhrer M. Treatment of paraneoplastic hyperammonemia in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with oral sodium phenylbutyrate. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):e8–10.

Vandewynckel YP, Geerts A, Verhelst X, Van Vlierberghe H. Cerebellar stroke in a low cardiovascular risk patient associated with sorafenib treatment for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Case Rep. 2014;2(1):4–6.

Sulaiman RA, Geberhiwot T. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. JIMD Rep. 2014;16:47–50.

Chiarelli M, De Simone M, Guttadauro A, Cioffi U. Fibrolamellar carcinoma in a 62 year-old patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46(10):959.

Okur A, Eser EP, Yilmaz G, Dalgic A, Akdemir UO, Oguz A, et al. Successful multimodal treatment for aggressive metastatic and recurrent fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(5):e328–32.

Zen Y, Vara R, Portmann B, Hadzic N. Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases with special reference to EpCAM. Histopathology. 2014;64(5):671–82.

Minutolo V, Licciardello A, Arena M, Minutolo O, Lanteri R, Arena G. Surgical resection of ruptured fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:679565.

De Gaetano AM, Nure E, Grossi U, Frongillo F, Russo R, Vecchio FM, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombus: an unreported association. Jpn J Radiol. 2013;31(10):706–12.

Berger C, Dimant P, Hermida L, Paulin F, Pereyra M, Tejo M. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy and fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicina (B Aires). 2012;72(5):425–7.

Wojcicki M, Lubikowski J, Post M, Chmurowicz T, Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Krawczyk M. Aggressive surgical management of recurrent lymph node and pancreatic head metastases of resected fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Jop. 2012;13(5):529–32.

Gras P, Truant S, Boige V, Ladrat L, Rougier P, Pruvot FR, et al. Prolonged complete response after GEMOX chemotherapy in a patient with advanced fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(1):169–72.

Koudah S, El Mouhadi S, Arrive L. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(1):5–6.

Brunel V, Cauliez B, Lacaze L, Riachi G, Gargala G, Francois A, et al. Liver mass in a young adult. Lancet. 2011;378(9797):1196.

Mroz RM, Korniluk M, Swidzinska E, Dzieciol J, Czaban J, Panek B, et al. Lung mass in a 28-year-old male: a case report of a rare tumor. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15(Suppl 2):95–7.

Terzis I, Haritanti A, Economou I. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report with distinct radiological features. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(1):2–5.

Chapuy CI, Sahai I, Sharma R, Zhu AX, Kozyreva ON. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy associated with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: case report, literature review, and proposed treatment algorithm. Oncologist. 2016;21(4):514–20.

Sethi S, Tageja N, Singh J, Arabi H, Dave M, Badheka A, et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy: a rare presentation of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(6):522–4.

Hashash JG, Thudi K, Malik SM. An 18-year-old woman with a 15-cm liver mass and an ammonia level of 342. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1157–402.

Alsina AE, Franco E, Nakshabandi A, Albers C, Kemmer N, Berry AC, et al. Successful liver transplantation for hyperammonemic fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3(4):e106.

Chan JS, Harding CO, Blanke CD. Postchemotherapy hyperammonemic encephalopathy emulating ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) deficiency. South Med J. 2008;101(5):543–5.

Suarez O, Perez M, Garzon M, Daza R, Hernandez G, Salinas C, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma and noncirrhotic hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Case Reports Hepatol. 2018;2018:7521986.

Khoo JJ, Clouston A. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Malays J Pathol. 2001;23(2):115–8.

Marrannes J, Gryspeerdt S, Haspeslagh M, van Holsbeeck B, Baekelandt M, Lefere P. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in a 65-year-old woman: CT features. JBR-BTR. 2005;88(5):237–40.

Lamberts R, Nitsche R, de Vivie RE, Peitsch W, Schauer A, Schuster R, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome as the primary manifestation of a fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Digestion. 1992;53(3-4):200–9.

Saab S, Yao F. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(10):1981–5.

Mansouri D, Van Nhieu JT, Couanet D, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Brugieres L, Cherqui D, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report with cytological features in a sixteen-year-old girl. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34(8):568–71.

Muramori K, Taguchi S, Taguchi T, Kohashi K, Furuya K, Tokuda K, et al. High aromatase activity and overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(5):e195–7.

Smith MT, Blatt ER, Jedlicka P, Strain JD, Fenton LZ. Best cases from the AFIP: fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiographics. 2008;28(2):609–13.

Sher ES, Migeon CJ, Berkovitz GD. Evaluation of boys with marked breast development at puberty. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1998;37(6):367–71.

Hany MA, Betts DR, Schmugge M, Schonle E, Niggli FK, Zachmann M, et al. A childhood fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with increased aromatase activity and a near triploid karyotype. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28(2):136–8.

McCloskey JJ, Germain-Lee EL, Perman JA, Plotnick LP, Janoski AH. Gynecomastia as a presenting sign of fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver. Pediatrics. 1988;82(3):379–82.

Agarwal VR, Takayama K, Van Wyk JJ, Sasano H, Simpson ER, Bulun SE. Molecular basis of severe gynecomastia associated with aromatase expression in a fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(5):1797–800.

Al-Matham K, Alabed I, Zaidi SZ, Qushmaq KA. Cold agglutinin disease in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: a rare association with a rare cancer variant. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(2):197–200.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts and by Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KH and AL developed the concept of the article. KH, AL, CR, MB, and AM developed the design and methodology. KH, AL, PM, DH, TL, and KHW contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lemekhova, A., Hornuss, D., Polychronidis, G. et al. Clinical features and surgical outcomes of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective analysis of a single-center experience. World J Surg Onc 18, 93 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01855-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01855-2