Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to explore the characteristics and prognostic information of estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-negative (ER+/PR−) male breast cancer.

Methods

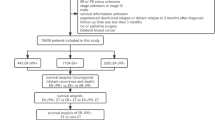

Using the US National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, we compared the demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcome of estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-positive (ER+/PR+) patients with ER+/PR− male breast cancer patients from 1990 to 2010. Two thousand three hundred twenty-two patients with ER+/PR+ tumors and 355 patients with ER+/PR− tumors were included in our study.

Results

ER+/PR− patients were younger (P = 0.008) and more likely to be African American (P < 0.001) while presented with higher histological grade (P < 0.001), larger tumor size (P = 0.010), and more invasion to the lymph nodes (P = 0.034) and distant sites (P < 0.001), thus later stage (P = 0.001). Despite higher chance of receiving chemotherapy (51.0% vs 36.5%, P < 0.001), ER+/PR− patients experienced significantly worse breast cancer-specific survival (BSCC) (P < 0.001) and shorter overall survival (OS) (P = 0.003). Multivariate Cox model confirmed that tumor size, lymph node invasion, metastasis, and surgery were independent prognostic factors of both BSCC and OS for ER+/PR− male breast cancer. Age at diagnosis and chemotherapy were significantly associated with OS but not with BSCC.

Conclusion

ER+/PR− male breast cancer was more aggressive and experienced shorter survival than ER+/PR+ patients. The prognosis was mainly associated with tumor size, lymph node invasion, metastasis, and surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Male breast cancer (MBC) is an uncommon disease, accounting for less than 1% of all breast cancer diagnoses in the USA [1]. However, the annual incidence was reported to increase from 1.0 per 100,000/year in the late 1970s to 1.2 per 100,000/year in 2000–2004 [2]. Due to its rarity, the epidemiology, tumor behavior, treatment, and prognosis remain poorly understood. Current knowledge was mainly based on small series of studies, except for the advancement made by the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. The results of part 1, a retrospective joint central study of 1822 MBC patients, and part 2, a 30-month prospective registry of 557 cases, had been partially released lately [3,4,5,6]; thus, further analysis and prospective trials are still yet to be conducted.

Suffering from lack of clinical trials and knowledge on molecular biology, clinicians have to extrapolate treatment strategies for MBC from female breast cancer (FBC) data, despite differences at the protein, genetic, and epigenetic level [7,8,9]. Although several recent studies have assessed the prognostic factors of MBC, the conclusions are controversial and often blighted by the small number of patients [10,11,12].

Testing for estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) markers has been recommended for all newly diagnosed breast cancer patients by the College of American Pathologists and American Society of Clinical Oncology [13]. Several studies have demonstrated high rates of ER positivity in MBC, for example, Cardoso et al. reported that up to 99.3% of tumors were ER-positive [3, 14, 15]. The range of PR expression is wider than ER among different published reports, from 58.8 to 96% [16]. In FBC, if human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) was negative, ER+/PR− and ER+/PR+ breast cancer would be categorized as luminal B subtype and luminal A subtype, respectively, with different prognosis. Given the fact that HER-2 was dominantly negative in MBC [3, 5, 17], we conducted this population-based study to compare ER+/PR− MBC with ER+/PR+ MBC and further investigate the clinical characterization and prognostic factors of ER+/PR− MBC.

Materials and methods

Data were obtained from the US National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database [18]. We selected patients diagnosed with breast cancer between 1990 and 2010 according to the following criteria: male, pathological diagnosis of invasive carcinoma, unilateral, ER-positive, and breast as the only primary site. Patients with unknown PR status were excluded. Data extraction was performed by SEER*Stat software version 8.3.2 based on the November 2015 data submission [19]. Marital status was divided into three categories: not married, married, and unknown, with the first one consisting of divorced, separated, single (never married), and widowed. The outcome of interests were breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS). The former was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of breast cancer death, and OS was defined as the interval from diagnosis to the death from any cause.

Our study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital, namely Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital Ethics Committee. No informed patient consent was needed.

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics were compared between ER+/PR+ and ER+/PR− subtypes using a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct survival curves. The multivariate Cox regression models were built to assess the independent association of all the variables with BCSS and OS in the ER+/PR+ and ER+/PR− cohorts (forward: LR). Stage, which was defined by tumor size, lymph node invasion, and distant metastasis, was excluded from the model to avoid interference among the variables. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using the Cox models. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 2677 male patients with ER+ invasive carcinoma were included in this study. Two thousand three hundred twenty-two patients had ER+/PR+ tumors, and 355 patients had ER+/PR− tumors. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to PR status. Compared with PR-positive patients, PR-negative patients were younger (P = 0.008), more likely to be African American (P < 0.001). PR-negative tumors tended to present with higher grade (P < 0.001), larger tumor size (P = 0.010), and more invasion to the lymph nodes (P = 0.034) and distant sites (P < 0.001), thus later stage (P = 0.001). Fifty-one percent of PR-negative patients received chemotherapy, significantly higher than PR-positive patients (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference between ER+/PR+ and ER+/PR− MBC patients in terms of laterality, marital status, surgery, and radiation therapy (P = 0.910, 0.331, 0.623, and 0.089, respectively).

Survival analysis

After a median follow-up of 82 months, 1313 deaths were reported among patients in this study, 625 of which were due to breast cancer. Compared with PR-positive patients, patients with PR-negative breast cancer experienced significantly worse BCSS (P < 0.001) and shorter OS (P = 0.003) (see Fig. 1).

In the PR-positive MBC cohort, laterality and radiation did not make it into the final Cox model (forward: LR) in the analysis of OS and BCSS. Race, age at diagnosis, marital status, histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status, metastasis, and surgery all exhibited independent prognostic significance. Chemotherapy could significantly improve OS (HR = 1.261, 95% CI 1.088–1.461, P = 0.002) but not BSCC, as shown in Table 2.

In the PR-negative MBC cohort, laterality, radiation, race, marital status, and histological grade were not included in the final Cox model (forward: LR) in the analysis of OS and BCSS. Tumor size, lymph node invasion, metastasis, and surgery were independent prognostic factors. Age at diagnosis and chemotherapy were significantly associated with OS but not with BCSS. Chemotherapy could reduce the risk of dying from all causes (HR = 1.492, 95% CI 1.073–2.076, P = 0.017), as shown in Table 3.

As age at diagnosis was related to OS in both the PR-positive and PR-negative patients, we constructed the survival curves and conducted a pair-wise comparison among different age groups to further explore the difference between PR-positive and PR-negative MBC, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 4. For PR-positive MBC, the OS of patients younger than 40 was not significantly different from patients aged 41 to 55 (P = 0.800) and 56 to 70 (P = 0.154) but better than patients aged 71 to 85 (P < 0.001) and older (P < 0.001). The OS of patients aged 41 to 55 was significantly better than the following groups (P = 0.010, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively). For PR-negative MBC, the OS of patients younger than 40, patients aged 41 to 55, and patients aged 56 to 70 did not change dramatically (P = 0.951, 0.772, and 0.738, respectively). Survival declined significantly with age after 70, as shown in Table 4.

Discussion

MBC is substantially different from FBC, arising with increasing frequency due to BRCA2 mutations with differential effects by gender of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [20]. The rarity of MBC resulted in difficulty in operating randomized, controlled clinical trials and limited prognostic information and suboptimal treatment. Only 3 out of the 12 breast cancer trials that included male patients are phase 3 clinical trials, and just 1 trial is actively recruiting [5]. The implications for PR positivity have long been a focus of debate. Some researchers recommended the elimination of PR testing from the routine diagnostic work-up of invasive breast cancer [13]. Other researchers advocated assessment of PR status to distinguish subsets of ER-positive and ER-negative tumors [21]. Also, PR status was suggested as a useful tool for selecting initial therapy, because ER+/PR− tumors might benefit more from initial treatment with an aromatase inhibitor [22]. However, tamoxifen is still the standard endocrine therapy in MBC patients [17]. In our study, we found that the clinical characteristics and prognosis of ER+/PR− MBC were different from ER+/PR+ MBC, the former being more aggressive and experiencing a much shorter OS and BCSS. Given the fact that normally endocrine therapy would be administered to both ER+/PR+ MBC and ER+/PR− MBC patients, the survival difference possibly lay more in tumor behavior than treatments. This verified the importance of PR testing. Besides, according to our study, the prognosis of ER+/PR− MBC patients was significantly related to tumor stage and surgery other than demographic factors like marital status and race; herein, early detection, diagnosis, and intervention were of great importance to improve the outcome of these patients.

The median age at diagnosis of MBC is 65–69 years old [3, 6, 23,24,25] in the West counties and a little bit younger in Asia [26] and the Middle East [27]. Most literature has validated the prognostic role of age at diagnosis [12, 24, 26, 28, 29]. Our study was in agreement with the previous research. Nevertheless, we found different effect of age between the PR-positive and PR-negative MBC. OS dropped significantly for PR-positive patients older than 55 years, while patients younger than 70 years old experienced similar OS in PR-negative group. Furthermore, age was not independently related to BCSS in PR-negative MBC patients. The analysis of EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program partially supported our results [3]. Compared with patients diagnosed ≤ 40 years old, patients diagnosed ≥ 75 years old experienced a 25% higher mortality risk. Nonetheless, the authors did not conduct strata analysis according to breast cancer subtypes, and only deaths following a distant relapse were considered breast cancer mortality event. We assume that older onset of age with a high presence of comorbidities could explain the divergence between OS and BCSS. 32.6% of MBC patients were diagnosed with comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease [26]. Nearly 40% of MBC patients died from causes unrelated to their breast cancer [24].

Histological grade is representative of the “aggressive potential” of the tumor and would be expected to predict the survival of MBC. Some literature did report that tumor grade was a predictor of OS and/or BCSS [25, 28, 30], so did our analysis of the PR-positive cohort. On the contrary, Vermeulen et al. [6] found that tumor grade was not independently associated with survival, so did our analysis of the PR-negative patients and some other research [3, 31]. Different “scoring systems” were applied for determining the grade of a breast cancer, including four-tier grading scheme and three-tier grading scheme, which undermined the comparison among different results. Also, the grading system that was initially developed for FBC may not be suitable in the MBC setting. Last, MBC could be a heterogenous disease with different subtypes exhibiting different prognostic patterns, as our work demonstrated.

Interestingly, chemotherapy was confirmed an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate Cox analyses of OS but did not reach significance with this test in BCSS, neither in ER+/PR+ nor ER+/PR− cohort, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. Since few studies analyzed OS and BCSS of MBC at the same time, our finding was not echoed. There might be some possibilities: first, the drugs somehow reduced the risk of dying from causes other than cancer; second, we did not use HER-2 status in the model, which was not available until 2010, so the conclusion might be partial. The application of the 21-gene breast recurrence score (RS) may shed some light on the option of chemotherapy. After testing 38 MBC patients, Turashvili et al. [32] found similar RS distribution in MBC and FBC patients. Besides, RS testing was declared to play a prognostic role in MBC [7]. Larger studies with different cohorts are needed to further identify the risk factors and optimize treatments for MBC patients.

We acknowledge some limitations to our study. We do not have the information regarding HER-2 status, as mentioned above. Also, as a retrospective analysis, our study may have introduced biases. Despite these limitations, our study, to our best knowledge, was the first to expound the characterizations and prognosis of PR-negative MBC. Also, our SEER-based study included the data on systemic treatments of this population, which was recently updated.

In conclusion, ER+/PR− MBC, compared with ER+/PR+ MBC, presented with more aggressive behavior and poorer survival. The prognosis was independently associated with stage and clinical intervention; thus, early diagnosis and individualized treatment were warranted to improve the outcome.

Abbreviations

- BCSS:

-

Breast cancer-specific survival

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FBC:

-

Female breast cancer

- HER-2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- MBC:

-

Male breast cancer

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- RS:

-

Recurrence score

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29.

Stang A, Thomssen C. Decline in breast cancer incidence in the United States: what about male breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(3):595–6.

Cardoso F, Bartlett JMS, Slaets L, van Deurzen CHM, van Leeuwen-Stok E, Porter P, et al. Characterization of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):405–17.

Doebar SC, Slaets L, Cardoso F, Giordano SH, Bartlett JM, Tryfonidis K, et al. Male breast cancer precursor lesions: analysis of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(4):509–18.

Gucalp A, Traina TA, Eisner JR, Parker JS, Selitsky SR, Park BH, et al. Male breast cancer: a disease distinct from female breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4921-9.

Vermeulen MA, Slaets L, Cardoso F, Giordano SH, Tryfonidis K, van Diest PJ, et al. Pathological characterisation of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:219–27.

Massarweh SA, Sledge GW, Miller DP, McCullough D, Petkov VI, Shak S. Molecular characterization and mortality from breast cancer in men. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(14):1396–404.

Piscuoglio S, Ng CK, Murray MP, Guerini-Rocco E, Martelotto LG, Geyer FC, et al. The genomic landscape of male breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(16):4045–56.

Rizzolo P, Navazio AS, Silvestri V, Valentini V, Zelli V, Zanna I, et al. Somatic alterations of targetable oncogenes are frequently observed in BRCA1/2 mutation negative male breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;7(45):74097–106.

Abreu MH, Afonso N, Abreu PH, Menezes F, Lopes P, Henrique R, et al. Male breast cancer: looking for better prognostic subgroups. Breast. 2016;26:18–24.

Gu L, Sun B, Zhang L-N, Zhang J, Zhang N. The prognostic value of clinical and pathologic features in nonmetastatic operable male breast cancer. Asian J Androl. 2016;18(1):90.

Choi MY, Lee SK, Lee JE, Park HS, Lim ST, Jung Y, et al. Characterization of Korean male breast cancer using an online nationwide breast-cancer database: matched-pair analysis of patients with female breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(16):e3299.

Hefti MM, Hu R, Knoblauch NW, Collins LC, Haibe-Kains B, Tamimi RM, et al. Estrogen receptor negative/progesterone receptor positive breast cancer is not a reproducible subtype. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(4):R68.

Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenberg PS. Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):232–9.

Sineshaw HM, Freedman RA, Ward EM, Flanders WD, Jemal A. Black/white disparities in receipt of treatment and survival among men with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(21):2337–44.

Zografos E, Gazouli M, Tsangaris G, Marinos E. The significance of proteomic biomarkers in male breast cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13(3):183–90.

Leon-Ferre RA, Giridhar KV, Hieken TJ, Mutter RW, Couch FJ, Jimenez RE, et al. A contemporary review of male breast cancer: current evidence and unanswered questions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-018-9761-x.

Available from: National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. http://seer.cancer.gov/.

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance E, and End Results Program. Turning Cancer Data Into Discovery. http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. Accessed 30 Nov 2016.

Fentiman IS. Male breast cancer is not congruent with the female disease. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;101:119–24.

Shen T, Brandwein-Gensler M, Hameed O, Siegal GP, Wei S. Characterization of estrogen receptor-negative/progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(11):1776–84.

Fuqua SA, Cui Y, Lee AV, Osborne CK, Horwitz KB. Insights into the role of progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):931–2 Author reply 2-3.

Leone JP, Leone J, Zwenger AO, Iturbe J, Vallejo CT, Leone BA. Prognostic significance of tumor subtypes in male breast cancer: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152(3):601–9.

Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer. 2004;101(1):51–7.

Madden NA, Macdonald OK, Call JA, Schomas DA, Lee CM, Patel S. Radiotherapy and male breast cancer: a population-based registry analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39(5):458–62.

Kwong A, Chau WW, Mang OWK, Wong CHN, Suen DTK, Leung R, et al. Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer in Hong Kong, Southern China: 1997–2006. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;21(4):1246–53.

Ndom P, Um G, Bell EM, Eloundou A, Hossain NM, Huo D. A meta-analysis of male breast cancer in Africa. Breast. 2012;21(3):237–41.

Leone JP, Zwenger AO, Iturbe J, Leone J, Leone BA, Vallejo CT, et al. Prognostic factors in male breast cancer: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;156(3):539–48.

Shahraki HR, Salehi A, Zare N. Survival prognostic factors of male breast cancer in southern Iran: a LASSO-Cox regression approach. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6773–7.

Masci G, Caruso M, Caruso F, Salvini P, Carnaghi C, Giordano L, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics in male breast cancer: a retrospective case series. Oncologist. 2015;20(6):586–92.

Arslan UY, Oksuzoglu B, Ozdemir N, Aksoy S, Alkis N, Gok A, et al. Outcome of non-metastatic male breast cancer: 118 patients. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):554–60.

Turashvili G, Gonzalez-Loperena M, Brogi E, Dickler M, Norton L, Morrow M, et al. The 21-gene recurrence score in male breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1530–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available on the following website: http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. The corresponding author would provide the raw files analyzed via e-mail on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJ analyzed and interpreted the patient data. FD was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. ZJ conceived the idea. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, JL., Zhang, JX. & Fu, DY. Characterization and prognosis of estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-negative male breast cancer: a population-based study. World J Surg Onc 16, 236 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1539-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1539-7