Abstract

Background

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents the most common histological subtype of primary gastrointestinal lymphoma and is a heterogeneous group of disease. Prognostic characterization of individual patients is an essential prerequisite for a proper risk-based therapeutic choice.

Methods

Clinical and pathological prognostic factors were identified, and predictive value of four previously described prognostic systems were assessed in 101 primary gastrointestinal DLBCL (PG-DLBCL) patients with localized disease, including Ann Arbor staging with Musshoff modification, International Prognostic Index (IPI), Lugano classification, and Paris staging system.

Results

Univariate factors correlated with inferior survival time were clinical parameters [age >60 years old, multiple extranodal/gastrointestinal involvement, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase and β2-microglobulin, and decreased serum albumin], as well as pathological parameters (invasion depth beyond serosa, involvement of regional lymph node or adjacent tissue, Ki-67 index, and Bcl-2 expression). Major independent variables of adverse outcome indicated by multivariate analysis were multiple gastrointestinal involvement. In patients unfit for Rituximab but received surgery, radical surgery significantly prolonged the survival time, comparing with alleviative surgery. Addition of Rituximab could overcome the negative prognostic effect of alleviative surgery. Among the four prognostic systems, IPI and Lugano classification clearly separated patients into different risk groups. IPI was able to further stratify the early-stage patients of Lugano classification into groups with distinct prognosis.

Conclusions

Radical surgery might be proposed for the patients unfit for Rituximab treatment, and a combination of clinical and pathological staging systems was more helpful to predict the disease outcome of PG-DLBCL patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal lymphoma, accounting for 30–40 % of the patients, in which diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most frequent histological subtype with a variable clinical outcome [1, 2]. Therefore, prognostic characterization of individual patients is an essential prerequisite for a proper risk-based therapeutic choice.

Surgery was once the standard procedure or a regular component of combined treatment modalities in primary gastrointestinal DLBCL (PG-DLBCL) [3]. The factors in favor of a surgical approach include the removal of primary lesions, availability of precise histological classification and staging, as well as avoidance of complications such as perforation or hemorrhage that may occur during radiotherapy and chemotherapy [4–6]. In the recent years, opinion has increasingly swung toward non-invasive treatment even for patients with resectable disease, so as to maintain their quality of life [7–9]. However, the benefit of a surgical approach remains controversial in the patients treated with Rituximab and chemotherapy/radiotherapy.

Several staging systems have been developed over the past decades to improve prognostic stratification of primary gastrointestinal lymphoma, mainly taking into account different clinical parameters. The classical Ann Arbor staging system is adapted for extranodal lymphoma, as proposed by Musshoff et al. [10]. International Prognostic Index (IPI) is originated from patients with DLBCL that consists of age, performance status, Ann Arbor stage, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and extranodal involvement [11]. Meanwhile, novel scores have been explored, namely Lugano classification and Paris staging system [12, 13], which combine clinical features with pathological findings of the tumors.

Although both clinical and pathological prognostic systems were effective in the patient series used to drive them, their utility needs testing in other patient populations of PG-DLBCL, particularly in those with accurate pathological data obtained by a surgical approach. Moreover, direct evaluation and comparison of these systems are limited in large -scale Chinese patients with localized disease in the Rituximab era. To address this issue, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 101 patients followed up in our Institution over the last 12 years to identify the main prognostic factors and to compare different staging systems in the prediction of survival in localized PG-DLBCL that received a surgical approach.

Methods

Patients

From January 2003 to October 2014, a total of 101 patients of localized PG-DLBCL received a surgical approach were included in this retrospective study and 49 patients who received chemotherapy alone were referred as control. PG-DLBCL was defined according to Lewin et al.: patients had to present gastrointestinal symptoms or predominant lesions in the gastrointestinal tract [14]. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, in accordance with the regulations of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards.

Diagnosis and staging systems

Pathological diagnosis was established according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [15]. The staging work-up included history and physical examination, blood cell counts and serum chemistry, bone marrow aspiration or biopsy, endoscopy of gastrointestinal tracts, and chest and abdominal tomography scan or positron emission tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT). The stage of lymphoma was assessed following the guidelines of Ann Arbor staging with Musshoff modification (Ie1/Ie2/IIe1/IIe2), IPI (low/low–intermediate/high–intermediate/high-risk), Lugano classification (I/II1/II2/IIE), and Paris staging system (TxNxMxBx), respectively. The macroscopic type of lymphoma (ulcerative, diffuse, or massive type), the depth of tumor invasion, as well as the involvement of regional lymph nodes and adjacent structure were determined based on histology of the resected tumor specimens.

Treatment and response

A standard radical gastrectomy is defined as a gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and resection of Nl and N2 lymph nodes [16]. Radical surgery for primary intestinal lymphoma is defined as completely primary mass resection and regional lymph nodes dissection. As for the alleviative surgery, the lesions were not completely resected, which is also called surgical debulking, including local mass resection (R1–R2), enterostomy, and simple perforation repair [17, 18].

The patients received a surgical approach, either alone or followed by chemotherapy (four to six standard dose of CHOP regimens) or combined with Rituximab (375 mg/m2). The treatment response was evaluated according to the WHO response criteria. Complete response (CR) was defined as no evidence of residual disease, partial response (PR) with at least 50 % reduction in tumor burden from the onset of treatment, and stable disease (SD) and progression disease (PD) with less than 50 % reduction in tumor burden or disease progression. Assessment of treatment response was evaluated by clinical follow-up, radiological, or laboratory studies, as determined by the clinician. The patients who had stable disease or partial response received second-line chemotherapy instead of radiotherapy.

Statistic analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease relapse or the last follow-up. Survival functions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Chi-square was used for comparison of the clinical data of the patients with different treatments. Multivariate survival analysis was performed using Cox regression model. Significant variables in the univariate analysis were selected as variables in the multivariate analysis for survival. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were evaluated using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Clinical characteristics

As shown in Table 1, 64 of the 101 patients (63 %) were <=60 years old and the median age was 57 years (ranged 18 to 82 years). There were 57 male and 44 female patients. All the patients presented gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal discomfort (67 cases, 66 %), severe gastrointestinal bleeding (16 cases, 16 %), obstruction or intussusceptions (10 cases, 10 %), diarrhea (3 cases, 3 %), abdominal mass (6 cases, 6 %), and perforation (2 cases, 2 %).

According to Ann Arbor staging with Musshoff modification, all the patients had localized disease (Ie to IIe2) with ECOG ≤2. Forty-two cases (44 %) presented with B symptoms. Multiple extranodal involvement and elevated serum LDH level were observed in 16 patients (16 %) and 24 patients (24 %), respectively. Fifty-one cases (50 %) had elevated β2-microglobulin (β2-MG), 25 cases (25 %) had hypoalbuminemia, and 45 cases (45 %) had anemia at diagnosis.

As for the sites of origin, the most frequent site was the stomach (gastric group; 48 cases, 48 %), followed by the duodenum and small bowel (17 cases, 17 %), ileocecal (16 cases, 15 %), and colorectal groups (15 cases, 15 %). The remaining 5 (5 %) patients (combined group) had both gastric and intestinal involvement.

Surgical approaches and chemotherapy

Surgical modalities included radical surgery and alleviative surgery (74 and 27 cases, respectively). Of the 74 patients who underwent radical surgery, 9 cases received surgery alone, and the remaining 65 cases were treated with chemotherapy alone, or combined with Rituximab (21 and 44 cases, respectively). Similar distribution was found in the 27 patients who underwent alleviative surgery (3, 8, and 16 cases, respectively, Table 1).

Pathological characteristics

Detailed pathological features of the tumors were available from operation (Table 2). Macroscopically, 12 tumors (12 %) were classified as ulcerative type, 18 (18 %) as diffuse type, and 71 (70 %) as massive type. Microscopically, the depth of invasion were limited to mucosa/submucosa (0), muscularis propria/subserosa (40, 40 %), beyond serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invasion of adjacent structures (43, 42 %), and involvement of adjacent structures or organs (18, 18 %). Involvement of regional lymph node and adjacent tissue were present in 53 and 22 patients (52 and 22 %, respectively). The high level (>75 %) of Ki-67 antigen was detected in the biopsy specimens of 25 cases (25 %). Bcl-2 expression was positive in 48 of the 101 patients (48 %).

Treatment outcome

The overall CR, PR, and SD/PD rate were 73, 15, and 12 %, respectively. The median follow-up time was 23 months (ranged 1 to 115 months). Overall, the 5-year RFS and OS rates were 82.5 ± 4.5 % and 83.9 ± 4.4 %, with median RFS and OS at 43.3 and 49.6 months, respectively.

By univariate analysis, the clinical characteristics significantly correlated with poor RFS and OS in the patients who received surgery were age older than 60 years old, the presence of multiple extranodal involvement, elevated serum LDH level and β2-MG, and decreased serum albumin (Table 1). Regarding pathological parameters, adverse prognostic factors included invasion depth beyond serosa, involvement of regional lymph nodes or adjacent tissue, high level of Ki-67, and Bcl-2 expression (Table 2).

Gastric, duodenum and small bowel, ileocecal, and colorectal group showed a higher survival rate than those with multiple sites involved (Table 1). To determine the role of surgery in the treatment of localized PG-DLBCL, we included 49 patients who received chemotherapy alone as control. As showed in Additional file 1: Table S1, no significant difference of clinical characteristics and Rituximab treatment was observed between the patients with surgery or those with chemotherapy alone. Surgery did not prolong the survival rate of localized PG-DLBCL patients, when compared with chemotherapy alone. However, in the patients without Rituximab treatment, mostly due to active infection of hepatitis B virus, the survival rate showed longer RFS and OS in cases who received radical surgery than those with alleviative surgery (RFS, 88.5 ± 4.4 % vs 69.5 ± 9.7 %; OS, 87.7 ± 4.8 % vs 72.3 ± 9.7 %, both P = 0.004). Addition of Rituximab significantly improved the survival of the patients who received alleviative surgery and chemotherapy (RFS, 92.9 ± 6.9 % vs 58.3 ± 18.6 %, P = 0.002; OS, 91.7 ± 8.0 % vs 71.4 ± 17.1 %, P = 0.001), instead of those who received radical surgery and chemotherapy (RFS, 93.8 ± 4.3 % vs 88.2 ± 7.8 %, P = 0.302; OS, 93.3 ± 4.6 % vs 88.2 ± 7.8 %, P = 0.333, Table 3).

By multivariate analysis, the significant independent prognostic factors for poor RFS and OS was multiple gastrointestinal involvement.

Staging systems

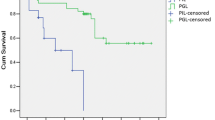

As illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, the staging systems varied from each other for defining specific risk subgroups. Ann Arbor staging with Musshoff modification could not further stratify the early-stage patients into different stages (stage I and stage II) (I, 5-year RFS, 86.8 ± 5.1 %; 5-year OS, 87.6 ± 5.3 % vs II, 5-year RFS, 77.9 ± 7.4 %; 5-year OS, 76.9 % ± 7.7 %, P = 0.423 and P = 0.428, respectively). IPI was able to define specific risk subgroups (low/low–intermediate (L–I)-risk and intermediate–high (I–H)/high-risk), but there was no prognostic difference between the low-risk subgroup and the L–I-risk group (5-year RFS and 5-year OS, P = 0.636 and P = 0.643, respectively), or between the high–intermediate (H–I)-risk subgroup and the high-risk group (5-year RFS and 5-year OS, P = 0.694 and P = 0.725, respectively). Using Lugano classification, the patients with advanced stage (IIE) had significantly shorter survival time than those with early stage (I and II) (IIE, 5-year RFS, 71.1 ± 11.0 %; 5-year OS, 76.0 ± 10.5 % vs I and II, 5-year RFS, 86.5 ± 4.5 %; 5-year OS, 85.4 ± 4.9 %, P = 0.039 and P = 0.044, respectively). Using Paris staging system, the patients in T3 and T4 showed no significant survival difference (T3, 5-year RFS, 71.3 ± 8.1 %; 5-year OS, 73.7 ± 8.0 % vs T4, 5-year RFS, 81.1 ± 9.9 %; 5-year OS, 80.4 ± 10.2 %, P = 0.661 and P = 0.695, respectively) (Table 4). Of note, according to IPI, Lugano early stage was grouped to IPI 0–2 (72 patients) and IPI 3–5 (10 patients) (Fig. 3). The latter had similar RFS and OS of the cases with Lugano late stage (P = 0.960 and P = 0.870, respectively). Thus, combination of clinical and pathological staging system was more efficient in classifying PG-DLBCL patients.

The RFS and OS curve according to Ann Arbor stage modified by Musshoff (a) and IPI score (b). The relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) curves according to Ann Arbor stage modified by Musshoff (a) and IPI score (b) show that these staging systems could define specific risk subgroups of patients with localized PG-DLBCL to some extent

The RFS and OS curves according to Lugano classification (a) and Paris staging system (b–d). The relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) curves according to Lugano classification (a) and Paris staging system (b–d) show that these staging systems could define specific risk subgroups of patients with localized PG-DLBCL to some extent

The RFS and OS curves according to the combination of Lugano classification and IPI. The relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) curves according to combination of Lugano classification and IPI shows that the combination of clinical and pathological staging system was more efficient in classifying PG-DLBCL patients

Discussion

PG-DLBCL represents the most common subtype of extranodal lymphoma, mainly involved in stomach and bowl [19]. Comparable to previous studies in Western and Asian countries [20–26], clinical parameters associated with deteriorated patient status (older age and hypoalbuminemia) as well as increased tumor burden (multiple extranodal and gastrointestinal involvement, elevated LDH, and β2-MG) were important factors indicating poor prognosis. Among all these univariate prognostic factors, multiple gastrointestinal involvement was independently related to adverse outcome of the patients. With the development of endosonography, radiological examination and PET-CT, patients with multiple gastrointestinal involvement could be easily distinguished nowadays. Also, pathological parameters negatively correlated with disease prognosis were identified, including tumor infiltration and involvement of regional lymph nodes, adjacent structures or organs, high Ki-67, and Bcl-2 expression. As previously reported, Ki-67 reflects high proliferation index and Bcl-2 is an important anti-apoptotic protein [27, 28], both of which correlate with the aggressive course in patients with DLBCL. Therefore, in addition to clinical prognosticators, pathological characteristics that are associated with biological behavior of the tumors are meaningful for appropriate prognostic settings of the patients with PG-DLBCL.

Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, is generally applied to treat B cell lymphoma. Like nodal lymphomas, the survival of primary gastric B cell lymphoma has been improved upon Rituximab treatment [29, 30]. Interestingly, the negative impact of alleviate surgery could be overcome by Rituximab treatment. Meanwhile, based on our data and the others [24, 31, 32], radical surgery may be considered as a therapeutic modality to patients unfit for Rituximab treatment (active infection of hepatitis B virus, etc.).

Staging systems are important to provide adequate treatment guidance. For the early stage of localized PG-DLBCL patients, Ann Arbor staging with Musshoff modification failed to give prognostic indications. Instead, IPI appeared more efficient in dividing the patients into two risk subgroups with distinct outcome, but it was unable to separate the survival of patients with low and L–I risks, as well as high and H–I risks [28, 33, 34]. Lugano classification [12, 25], including major pathological parameters like the depth of infiltration and infiltration of adjacent organs, also proved efficient. Interestingly, our data showed that IPI in conjunction with Lugano classification could further improve their capacity to discriminate the important risk subgroups. Therefore, the combination of clinical and pathological staging systems is optimal to predict the prognosis of PG-DLBCL.

Conclusions

Non-surgical treatment becomes an optimal therapeutic modality for localized PG-DLBCL in the Rituximab era. Addition of Rituximab might overcome the negative prognostic effect of alleviative surgery. The combination of pathological staging system and clinical system is optimal for prognosis prediction in patients with PG-DLBCL.

Abbreviations

- CR:

-

complete response

- DLBCL:

-

diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- IPI:

-

International Prognostic Index

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PD:

-

progression disease

- PG-DLBCL:

-

primary gastrointestinal DLBCL

- PR:

-

partial response

- RFS:

-

relapse-free survival

- SD:

-

stable disease

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- β2-MG:

-

β2-microglobulin

References

Bautista-Quach MA, Ake CD, Chen M, Wang J. Gastrointestinal lymphomas: morphology, immunophenotype and molecular features. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(3):209–25.

Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:697–707.

Rackner VL, Thirlby RC, Ryan Jr JA. Role of surgery in multimodality therapy for gastrointestinal lymphoma. Am J Surg. 1991;161:570–5.

Pascual M, Sanchez-Gonzalez B, Garcia M, Pera M, Grande L. Primary lymphoma of the colon. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:74–8.

Shimada S, Gen T, Okamoto H. Malignant gastric lymphoma with spontaneous perforation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4251.

Alevizos L, Gomatos IP, Smparounis S, Konstadoulakis MM, Zografos G. Review of the molecular profile and modern prognostic markers for gastric lymphoma: how do they affect clinical practice? Can J Surg. 2012;55:117–24.

Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Ponzoni M. The role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the treatment of diffuse large B-cell and marginal zone lymphomas of the stomach. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:470–9.

Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Digestion. 2013;87:182–8.

Selcukbiricik F, Tural D, Elicin O, Berk S, Ozguroglu M, Bese N, et al. Primary gastric lymphoma: conservative treatment modality is not inferior to surgery for early-stage disease. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:951816.

Musshoff K, Schmidt-Vollmer H. Proceedings: Prognosis of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas with special emphasis on the staging classification. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1975;83:323–41.

A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994.

Rohatiner A, D’Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, et al. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5(5):397–400.

Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Dragosics B, Morgner A, Wotherspoon A, De Jong D. Paris staging system for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas. Gut. 2003;52:912–3.

Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978;42:693–707.

Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;523–531.

Avilés A1, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Huerta-Guzmán J, Cuadra I, Alvarado I, et al. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240(1):44–50.

Gou HF1, Zang J, Jiang M, Yang Y, Cao D, Chen XC. Clinical prognostic analysis of 116 patients with primary intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29(1):227–234.

Gobbi PG1, Ghirardelli ML, Cavalli C, Baldini L, Broglia C, Clò V, et al. The role of surgery in the treatment of gastrointestinal lymphomas other than low-grade MALT lymphomas. Haematologica. 2000;85(4):372–380.

Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Wilson WH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma-treatment approaches in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:12–23.

Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18):3861–73.

Landolsi A, Chabchoub I, Limem S, Gharbi O, Chaafai R, Hochlef M, et al. Primary digestive tract lymphoma in central region of Tunisia: anatomoclinical study and therapeutic results about 153 cases. Bull Cancer. 2010;97(4):435–43.

Yin WJ, Wu MJ, Yang HY, Zhu X, Sun WY. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of 216 cases with primary gastrointestinal tract non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2013;34(5):377–82.

Cheung MC, Housri N, Ogilvie MP, Sola JE, Koniaris LG. Surgery does not adversely affect survival in primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:59–64.

Shawky H, Tawfik H. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a retrospective study with emphasis on prognostic factors and treatment outcome. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2008;20(4):330–41.

Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97:2462–73.

Papaxoinis G, Papageorgiou S, Rontogianni D, Kaloutsi V, Fountzilas G, Pavlidis N, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 128 cases in Greece. A Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study (HeCOG). Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2140–6.

He X, Chen Z, Fu T, Jin X, Yu T, Liang Y, et al. Ki-67 is a valuable prognostic predictor of lymphoma but its utility varies in lymphoma subtypes: evidence from a systematic meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:153.

Tibiletti MG, Martin V, Bernasconi B, Del Curto B, Pecciarini L, Uccella S, et al. BCL2, BCL6, MYC, MALT1, and BCL10 rearrangements in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: a multicenter evaluation of a new set of fluorescent in situ hybridization probes and correlation with clinical outcome. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:645–52.

Lee L, Crump M, Khor S, Hoch JS, Luo J, Bremner K, et al. Impact of rituximab on treatment outcomes of patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma: a population-based analysis. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:481–8.

Li X, Shen W, Cao J, Wang J, Chen F, Wang C, et al. Treatment of gastrointestinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma in China: a 10-year retrospective study of 114 cases. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1721–9.

Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Trastulli S, Cavaliere D, Covarelli P, Listorti C, et al. Surgical treatment of primitive gastro-intestinal lymphomas: a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:145.

Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18):3874–83.

Tay K, Tai D, Tao M, Quek R, Ha TC, Lim ST. Relevance of the International Prognostic Index in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e14; author reply e15.

Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, Glass B, Schmitz N, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Standard International Prognostic Index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2373–80.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81172254, 81101793, and 81325003), the Shanghai Commission of Science and Technology (11JC1407300, 14140903100, and 14430723400), and the Program of Shanghai Subject Chief Scientists (13XD140Z700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SZ, LW, DY, YS, SC, LZ, YQ, and ZS collected and analyzed the clinical data and drafted the manuscript. WZ and QL carried out the manuscript editing and review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Shengting Zhang, Li Wang and Dong Yu contributed equally to this work.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Clinical characteristics and survival rate of patients with localized PG-DLBCL. It shows the clinical characteristics and Rituximab treatment between localized PG-DLBCL patients with surgery and those with chemotherapy alone. (PDF 276 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Wang, L., Yu, D. et al. Localized primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B cell lymphoma received a surgical approach: an analysis of prognostic factors and comparison of staging systems in 101 patients from a single institution. World J Surg Onc 13, 246 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0668-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0668-5