Abstract

Background

Over the past few decades the benefits of assessing Quality of Life (QoL) and mental health in patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) have steadily increased with limited studies relating to the most useful method to assess these patients. This study aims to identify, review, summarise, and evaluate the methodological quality for the most validated commonly used health-related QoL and mental health assessment measurements in diabetic patients.

Methods

All original articles published on PubMed, MedLine, OVID, The Cochrane Register, Web of Science Conference Proceedings and Scopus databases were systematically reviewed between 2011 and 2022. A search strategy was developed for each database using all possible combinations of the following keywords: “type 2 diabetes mellitus”, “quality of life”, mental health”, and “questionnaires”. Studies conducted on patients with T2DM of ≥ 18 years with or without other clinical illnesses were included. Articles designed as a literature or systematic review conducted on either children or adolescents, healthy adults and/or with a small sample size were excluded.

Results

A total of 489 articles were identified in all of the electronic medical databases. Of these articles, 40 were shown to meet our eligibility criteria to be included in this systematic review. Approximately, 60% of these studies were cross-sectional, 22.5% were clinical trials, and 17.5% of cohort studies. The top commonly used QoL measurements are the SF-12 identified in 19 studies, the SF-36, included in 16 studies, and the EuroQoL EQ-5D, found in 8 studies. Fifteen (37.5%) studies used only one questionnaire, while the remaining reviewed (62.5%) used more than one questionnaire. Finally, the majority (90%) of studies reported using self-administered questionnaires and only 4 used interviewer mode of administration.

Conclusion

Our evidence highlights that the commonly used questionnaire to evaluate the QoL and mental health is the SF-12 followed by SF-36. Both of these questionnaires are validated, reliable and supported in different languages. Moreover, using single or combined questionnaires as well as the mode of administration depends on the clinical research question and aim of the study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the increasing recognition of the impact of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) on Quality of Life (QoL), mental health and overall physical and psychological health along with their useful measurement instruments has been well addressed in scientific literature [1]. The benefits of evaluating QoL and mental health in patients with T2DM have been appreciated. This includes the evaluation of the burden of the disease and its complications, which may contribute to the development of the most appropriate management and treatment plans in these vulnerable patient groups [2].

Moreover, physicians caring for patients with comorbid chronic illnesses that affect their QoL and mental health, such as T2DM, need to prioritise their diabetes management to ensure better care with the aim to focus on how healthcare systems influence these decisions [3]. This includes the stability of these decisions over time, with continuous surveillance based on proper and validated measurements [3,4,5,6].

Overall, the nature of QoL is complex and multidimensional with a variation in tools used between studies. The Australian Centre for Quality of Life’s directory of instruments reflects this further where there are more than 1000 variables included and although these intend to measure QoL each contains a variety of dependent variables [7]. Findings from other studies have linked the wrong measure to the concept of interest and there are numerous occasions where incorrect or different tools have been used or where their data is misinterpreted as QoL [8, 9]. Moreover, this will emphasise the importance of selecting an ideal reliable and valid measure that is useful to use throughout different cultures. Also, it should include a broad range of potentially independent domains covering all critical aspects of QoL [10].

Furthermore, the assessment of mental health in patients with diabetes requires multiple transitions geographically and socially. In addition, there is a need to identify patients lacking medical follow-up and are therefore, at increasing risk of poor mental health status including psychosocial problems such as depression, diabetes-emotional distress, anxiety, eating disorders, and cognitive impairment [11]. Hence, it is essential for clinicians to use a standardised tool that is of dynamic construct that incorporates comprehensiveness, sensitivity, and balance relative to subjectivity and brevity to help identify gaps and monitor psychological well-being and care among adult patients with T2DM. However, to date, measuring QoL and mental health outcomes in these patients remains a challenge and there are limited studies evaluating the quality of these tools.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to identify, summarise, and evaluate the methodological quality for the most commonly used and validated health-related QoL and mental health assessment measurements in patients with T2DM.

Methodology

The Systematic review was conducted on QoL, and mental health surveys published in PubMed, MedLine, OVID, The Cochrane Register, Web of Science Conference Proceedings and Scopus databases between the 1st of January 2011 and the 31st of July 2022. In addition, reference lists of the included studies and previous reviews on the topic were hand searched for potentially relevant studies. Search terms for each database included ‘type 2 diabetes mellitus’, ‘quality of life’, ‘mental health’, and ‘questionnaires’. No language restrictions were applied. We performed a systematic search in accordance with the Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses protocols (PRISMA) statement 2020 [12]. Our formulated research question was based on Participants, Concept, and Context (PCC) on ‘What is the most recent validated and commonly used measurement or questionnaire to assess the quality of life and mental health among adult diabetic patients in different languages?’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

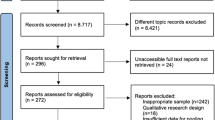

All studies conducted during the last decade or more (1st of January 2011 to 31st of July 2022) were considered to be eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) Population-based studies; 2) Among adults sharing common characteristics and health conditions including T2DM; 3) Studies focusing on health-related QoL and mental health assessment questionnaires or surveys; 4) Any studies conducted on 50 patients or more; 5) Surveys mentioned in conference abstracts were only considered if sufficient information were available for data extraction (Fig. 1). All publications were reviewed in full text to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria or not by two authors independently (Fig. 1).

Synthesis and data extraction

According to the eligibility criteria, the main author (O.A.) carefully scanned the titles and abstracts to address any duplicated or irrelevant studies from the initial databases, PubMed, and Scopus.

This was followed by reviewing all chosen articles in their full manuscript and filling in a pre-structured table that summarises and assesses the quality of the selected studies and any general information (Table 1). The table was designed into two sections one to cover the study characteristics and the other for study quality including the following items/ categories: 1) The primary author’s name; 2) Year of publication; 3) Study location; 3) Study design; 4) Target population (included the number of participants, age, and gender); 5) Main objectives and questionnaires; 6) Mode of questionnaire administration; 7) Validity; 8) Reproducibility; 9) Responsiveness of the participants; 10) Type of bias; 11) Languages support (Table 1).

A 10% random sample was checked by a second reviewer (K.H.) to check for the search and reviewing of the articles, references, and any additional relevant publications that may have been missed by the initial electronic databases was finally carried out independently by two senior examiners. Any inconsistencies were discussed by a third reviewer (J.F.) for a final decision.

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of each included study in terms of validity, reliability, and consistency was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklists (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools) for cohort, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and cross-sectional studies which was the most appropriate and applicable tool for this review [13]. The JBI checklist for cohort studies consists of 11 items, while 13 items for RCTs, and 8 items for cross-sectional studies. Each item was answered with either a Yes, No, Unclear, or Not Applicable response.

The categories of the studies were divided into: High quality (if 80% or more of the items were answered with a yes), Moderate (if more than 60% of the items were answered with a yes), and Low (if less than 60% of the items were answered with yes). Any study categorized as high or moderate quality was eligible to be included in this review. Any disagreement between the reviewers was solved by a discussion with the third reviewer (J.F.).

Results

Search and eligible studies

A total of 489 articles were identified in six electronic medical databases, 343 of which were selected (58.6% from Scopus) during the first screening (Fig. 1). Following the first screening, 109 articles were identified and subjected to the next level of screening after reading the titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). Of these, 68 articles were considered potentially eligible after reviewing the full text (Fig. 1). Subsequently, 28 articles were excluded based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and there were 21 articles [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] among them considered as low quality and excluded based on the JBI quality appraisal checklists used in this review (Fig. 1) (Table 2). Finally, 40 articles were shown to meet our eligibility criteria and were, therefore, included in this systematic review (Fig. 1) (Table 1).

Study characteristics and QoL measurements

The majority of the studies were cross-sectional 60% [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], followed by 22.5% clinical trial [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], and 17.5% cohort [68,69,70,71,72,73,74]; with overall response rates ranging between 40 and 98% among adult patients with T2DM.

The following questionnaires used in the QoL assessment included the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36), the Medical Outcomes Short Form 12 (SF-12), the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the EuroQoL EQ-5D, The World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief (WHOQOL-BREF), the 17-items Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS-17), the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life (ADDQoL19), the Diabetes‑Specific Quality of Life (DMQoL), and the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQoLLite). Other questionnaires used evaluated the mental health combined with QoL assessment. This included the Beck Depression Inventory, the World Health Organisation—Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), the Chronic Illness Care (PACIC), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale questionnaires (CES-D), the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) scale, the Confidence in Diabetes Self-Care (CIDS) scale, the 12-item Diabetes Support Scale (DSS), the Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey-II (HFS-II), the Health Care Climate-Short Form (HCC-SF), the Global Satisfaction with Diabetes Treatment (GSDT), the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities measure (SDSCA-6), the Barriers to Medications (BM), the Perceived Social Support (PSS), and The Empowerment Scale-Short Form (DES-SF).

Main findings

The six top commonly used QoL measurements included the SF-12 which was found in 19 studies [35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 60, 66, 68, 70,71,72,73], the SF-36, identified in 16 studies [36, 42, 44, 47, 50, 55, 57,58,59, 61,62,63,64,65, 67, 69], the EuroQoL EQ-5D, included in 8 studies [37, 41, 44, 55, 60, 71,72,73], the PHQ-9, found in five studies [35, 40, 60, 66, 74], the WHOQOL-BREF, evaluated in two studies [40, 52], and the ADDQoL19, identified in two studies [42, 46].

Fifteen (37.5%) studies used only one questionnaire. In this regard, the SF-12, was used as a single questionnaire in seven studies [39, 43, 45, 48, 51, 53, 70], the SF-36 in six studies [50, 61,62,63,64,65], the EuroQoL EQ-5D in one study [37] and the ADDQoL19 in one study [46]. However, the remaining reviewed studies (62.5%) used more than one questionnaire.

In terms of mental health measurements, there were four questionnaires that were commonly used which combined with QoL questionnaires namely the WHO-5 in three of the reviewed studies [38, 66, 74], the BDI in three studies [47, 57, 67], the PAID in three studies [56, 66, 74], and lastly the PACIC, found in two studies [38, 49].

Most of the studies (90%) reported using self-administered questionnaires with only four [51, 53, 68, 70] identified to use interviewer mode of administration. Moreover, all of the studies indicated that the questionnaires used were validated, reliable and that they supported different languages.

Discussion

The present systematic review indicates that the SF-12 questionnaire is the most appropriate and commonly used measurement to assess QoL and mental health followed by the SF-36, the EuroQoL EQ-5D, the PHQ-9, the WHOQOL-BREF, and the ADDQoL19. This questionnaire was used in several studies with different methodological approaches and was confirmed to be validated, reliable, less time-consuming, easy to use and available in many languages [75]. Other attributes of the SF-12 questionnaire include that it is a self-administered generic measurement and large-scale, population-based health inventory that has been developed to measure both the physical and mental health aspects of a patient [75]. It is effective and efficient with a completion time of fewer than five minutes [75]. Moreover, it has the exact eight health domains (Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Role Emotional, Mental Health, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, and Social Functioning) similar to SF-36 but with one or two items per domain and without any notable statistical difference especially for studies with a large sample size [75]. These were the significant advantages of using SF-12 over SF-36 while the disadvantages were considered as less in represents or comprehensiveness of the content of health measures and lacking of the statistical precision of mental and physical components scores compared to SF-36 [75].

One of the largest randomized controlled trials (RCTs) titled Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) conducted on 5,145 overweight or obese with T2DM assessed the effect of long-term lifestyle modification on QoL and depression symptoms using the BDI and SF-36 questionnaires as the main measurement for their primary outcomes. Concerns included a shallow response rate by fewer than 40% of patients in the final year of the study possibly due to the high dropout rate and lengthy QoL questionnaire [67]. Another RCT was conducted among 1,922 patients with T2DM to evaluate the effect of two different insulin therapy on QoL using the SF-36 alone. The authors of this study observed that there was a lack of a sleep variable on the questionnaire which was considered as a study limitation. There was no information relating to the response rate in this study [61]. The remaining trials that were included in the present review used the SF-36 with a response rate between 70%-98%; with the exception of one controlled clinical trial that used the SF-12 combined with different questionnaires and most of which had weaknesses with respect to randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment [59, 60, 62,63,64,65,66].

Another population-based cohort study on adults with T2DM conducted on 1,064 participants to assess the impact of diabetic retinopathy on QoL used the SF-12 where interviewers had the questionnaire administered in either English or another language [68]. This was similar to a population-based German cohort study that used the SF-12 to examine the change of QoL in 1,046 diabetic patients through a face-to-face questionnaire administered at baseline where the response rate was between 67 to 84% [70]. However, most of the other cohort studies included in this review preferred to use the SF-12 as a main questionnaire for their studies [71,72,73].

A longitudinal cross-sectional study conducted to identify the determinants of poor QoL in 1,826 Chinese diabetic patients who used the SF-12 over 24 months (through a phone interview) had a response rate between 75.5% and 59.7% [51]. This study used a similar methodological approach with another longitudinal cross-sectional study regarding the association between depression and QoL among 1,033 adults with T2DM addressed by interviews throughout the study using the SF-12 questionnaire alone [53]. It has been plausible that the majority of the cross-sectional studies matched with cohort studies in terms of using the SF-12 as their primary questionnaire and through interview mood of administration [35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 54].

Strengthens and limitations

The main strength of this review is that we comprehensively reviewed the body of evidence that focused on the most common and widely used publications over the last decade. This study identified the most common, widely used efficient and validated QoL and mental health questionnaire over a large number of publications for more than a decade in different languages. There are some weaknesses due to potential biases identified from the included studies especially the self-reported and non-response bias as well as the differences in response rates. Another weakness is the lack of standard terminology which may possibly cause misleading results. Lastly, the huge heterogeneity in the study designs, methodology, and sample size has limited our ability to quantify any differences through a meta-analysis.

Conclusion

In the backdrop of the growing prevalence of this disease worldwide there has been limited information on the most efficient and commonly used questionnaire for the diabetic patient. Our review found evidence of the effects of six different QoL and mental health questionnaires. Findings identified the SF-12 as the most validated, time efficient and effective questionnaire that allows cross-culture adaption which can be used in population-based studies across the world. These results encourage the use of SF-12 in adult patients with T2DM as a useful screening measure for identifying and monitoring mental health issues that may assist with target treatment and prevention. The wide range of tools used to assess QoL, methodology of administration, clinical research question and limited sample size used by studies hinder direct comparisons in patients with T2DM. Future large multicentre prospective research is recommended to help clarify causality on associations between mental health, QoL and any barriers in people with T2DM involving individuals from different cultural backgrounds.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- SF-12:

-

Medical outcomes short form 12

- SF-36:

-

Medical outcomes short form 36

References

The DCCT Research Group. Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT). Diabetes Care. 1988;11(9):725–32.

Jacobson AM, de Groot M, Samson JA. The evaluation of two measures of quality of life in patients with type I and type II diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(4):267–74.

Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–31.

Granata AV, Hillman AL. Competing practice guidelines: using cost-effectiveness analysis to make optimal decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(1):56–63.

Coffield AB, et al. Priorities among recommended clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(1):1–9.

Maciosek MV, et al. Methods for priority setting among clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(1):10–9.

Directory of Instruments. 2019; Available from: https://www.acqol.com.au/instruments.

Speight J, Reaney MD, Barnard KD. Not all roads lead to Rome-a review of quality of life measurement in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26(4):315–27.

Polonsky WH. Understanding and assessing diabetes-specific quality of life. Diabetes spectrum. 2000;13(1):36.

The Whoqol G. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties1This paper was drafted by Mick Power and Willem Kuyken on behalf of the WHOQOL Group. The WHOQOL group comprises a coordinating group, collaborating investigators in each of the field centres and a panel of consultants. Dr. J. Orley directs the project. The work reported on here was carried out in the 15 initial field centres in which the collaborating investigators were: Professor H. Herrman, Dr. H. Schofield and Ms. B. Murphy, University of Melbourne, Australia; Professor Z. Metelko, Professor S. Szabo and Mrs. M. Pibernik-Okanovic, Institute of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases and Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb, Croatia; Dr. N. Quemada and Dr. A. Caria, INSERM, Paris, France; Dr. S. Rajkumar and Mrs. Shuba Kumar, Madras Medical College, India; Dr. S. Saxena and Dr. K. Chandiramani, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India; Dr. M. Amir and Dr. D. Bar-On, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheeva, Israel; Dr. Miyako Tazaki, Department of Science, Science University of Tokyo, Japan and Dr. Ariko Noji, Department of Community Health Nursing, St. Luke's College of Nursing, Japan; Professor G. van Heck and Dr. J. De Vries, Tilburg University, The Netherlands; Professor J. Arroyo Sucre and Professor L. Picard-Ami, University of Panama, Panama; Professor M. Kabanov, Dr. A. Lomachenkov and Dr. G. Burkovsky, Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia; Dr. R. Lucas Carrasco, University of Barcelona, Spain; Dr. Yooth Bodharamik and Mr. Kitikorn Meesapya, Institute of Mental Health, Bangkok, Thailand; Dr. S. Skevington, University of Bath, U.K.; Professor D. Patrick, Ms. M. Martin and Ms. D. Wild, University of Washington, Seattle, U.S.A. and Professor W. Acuda and Dr. J. Mutambirwa, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe. In addition to the expertise provided from the centres, the project has benefited from considerable assistance from: Dr. M. Bullinger, Dr. A. Harper, Dr. W. Kuyken, Professor M. Power and Professor N. Sartorius.1. Social Science & Medicine. 1998; 46(12):1569–85.

Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312(7):691–2.

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71.

Ma L-L, et al. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: what are they and which is better? Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):7.

Cykert DM, et al. The association of cumulative discrimination on quality of care, patient-centered care, and dissatisfaction with care in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(1):175–9.

Rani M, Kumar R, Krishan P. Metabolic correlates of health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pharm Pract. 2019;32(4):422–7.

Babenko AY, et al. Mental state, psychoemotional status, quality of life and treatment compliance in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(2):113–20.

Haidari F, et al. The relationship between metabolic factors and quality of life aspects in type 2 diabetes patients. Res J Pharm Tech. 2017;10(5):1491–6.

Pati S, et al. Impact of comorbidity on health-related quality of life among type 2 diabetic patients in primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2020;21:e9.

Thapa S, et al. Health-related quality of life among people living with type 2 diabetes: a community based cross-sectional study in rural Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1171.

Sionti V, et al. Quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Int J Pharmaceu Healthcare Marketing. 2019;13(1):57–67.

Altınok A, Marakoğlu K, Kargın N. Evaluation of quality of life and depression levels in individuals with Type 2 diabetes. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(2):302–8.

Mikailiūkštienė A, et al. Quality of life in relation to social and disease factors in patients with type 2 diabetes in Lithuania. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:165–74.

Dalal J, et al. Association between dissatisfaction with care and diabetes self-care behaviors, glycemic management, and quality of life of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Educ. 2020;46(4):370–7.

Nyoni AM, et al. Profiling the mental health of diabetic patients: a cross-sectional survey of Zimbabwean patients. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):772.

Olukotun O, et al. Influences of demographic, social determinants, clinical, knowledge, and self-care factors on quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: black-white differences. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(4):1172–83.

Sato M, Yamazaki Y. Work-related factors associated with self-care and psychological health among people with type 2 diabetes in Japan. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;14(4):520–7.

Walker RJ, et al. Effect of diabetes self-efficacy on glycemic control, medication adherence, self-care behaviors, and quality of life in a predominantly low-income, minority population. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(3):349–55.

Baruah MP, et al. Impact of anti-diabetic medications on quality of life in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2021;25(5):432–7.

Costa MSA, Machado JC, Pereira MG. Longitudinal changes on the quality of life in caregivers of type 2 diabetes amputee patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(4):979–88.

Hu F, et al. The association between social capital and quality of life among type 2 diabetes patients in Anhui province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:786.

Ebrahimi H, et al. Effect of family-based education on the quality of life of persons with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. J Nurs Res. 2018;26(2):97–103.

Abraham AM, et al. Efficacy of a brief self-management intervention in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial from India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(6):540–8.

Kempf K, Martin S. Autonomous exercise game use improves metabolic control and quality of life in type 2 diabetes patients - a randomized controlled trial. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:57.

Hashimoto Y, et al. Association between sleep disorder and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20(1):98.

Green AJ, Fox KM, Grandy S. Self-reported hypoglycemia and impact on quality of life and depression among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;96(3):313–8.

Schunk M, et al. Health-related quality of life in subjects with and without Type 2 diabetes: Pooled analysis of five population-based surveys in Germany. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):646–53.

Siersma V, et al. Importance of factors determining the low health-related quality of life in people presenting with a diabetic foot ulcer: The Eurodiale study. Diabet Med. 2013;30(11):1382–7.

Pintaudi B, et al. Correlates of diabetes-related distress in type 2 diabetes: Findings from the benchmarking network for clinical and humanistic outcomes in diabetes (BENCH-D) study. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(5):348–54.

Adriaanse MC, et al. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on quality of life in type 2 diabetes patients. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(1):175–82.

Chew BH, Mohd-Sidik S, Shariff-Ghazali S. Negative effects of diabetes-related distress on health-related quality of life: An evaluation among the adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in three primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):187.

Shi L, et al. Is hypoglycemia fear independently associated with health-related quality of life? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):167.

Kuznetsov L, et al. Diabetes-specific quality of life but not health status is independently associated with glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of the ADDITION-Europe trial cohort. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104(2):281–7.

Bourdel-Marchasson I, et al. Correlates of health-related quality of life in French people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101(2):226–35.

Wermeling PR, et al. Both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidity are related to health status in well-controlled type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:121.

Reach G, Pautremat VL, Gupta S. Determinants and consequences of insulin initiation for type 2 diabetes in France: Analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:1007–23.

Donald M, et al. Mental health issues decrease diabetes-specific quality of life independent of glycaemic control and complications: Findings from Australia’s living with diabetes cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):170.

Zurita-Cruz JN, et al. Health and quality of life outcomes impairment of quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):1–7.

Williams JS, et al. Patient-centered care, glycemic control, diabetes self-care, and quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(10):644–9.

Jayasinghe UW, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life of Australian chronically-ill adults: Patient and physician characteristics do matter. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):102.

Pawaskar M, et al. Impact of the severity of hypoglycemia on health - Related quality of life, productivity, resource use, and costs among US patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32(5):451–7.

Wan EYF, et al. Main predictors in health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(11):2957–65.

Saffari M, et al. The role of religious coping and social support on medication adherence and quality of life among the elderly with type 2 diabetes. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(8):2183–93.

Alenzi EO, Sambamoorthi U. Depression treatment and health-related quality of life among adults with diabetes and depression. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(6):1517–25.

Abbatecola AM, et al. Diabetes-related quality of life is enhanced by glycaemic improvement in older people. Diabet Med. 2015;32(2):243–9.

Janssen LMM, et al. Burden of disease of type 2 diabetes mellitus: cost of illness and quality of life estimated using the Maastricht Study. Diabet Med. 2020;37(10):1759–65.

Sacre JW, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions on psychosocial and behavioural outcomes among Australian adults with type 2 diabetes: Findings from the PREDICT cohort study. Diabetic Medicine. 2021;38(9):e14611.

Selenius JS, et al. Impaired glucose regulation, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001568.

Nicolucci A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating a second-line glucose-lowering therapy: The DISCOVER study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;180:108974.

Cai J, et al. Impact of canagliflozin treatment on health-related quality of life among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pooled analysis of patient-reported outcomes from randomized controlled trials. Patient. 2018;11(3):341–52.

Al Sayah F, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA. Association of inadequate health literacy with health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and depression: secondary analysis of a controlled trial. Canadian J Diabetes. 2015;39(4):259–65.

Freemantle N, et al. Insulin degludec improves health-related quality of life (SF-36®) compared with insulin glargine in people with Type 2 diabetes starting on basal insulin: A meta-analysis of phase 3a trials. Diabet Med. 2013;30(2):226–32.

Myers VH, et al. Exercise training and quality of life in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):1884–90.

Löndahl M, Landin-Olsson M, Katzman P. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves health-related quality of life in patients with diabetes and chronic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2011;28(2):186–90.

Williams ED, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an automated, interactive telephone intervention (TLC Diabetes) to improve type 2 diabetes management: Baseline findings and six-month outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–1.

Nicolucci A, et al. Relationship of exercise volume to improvements of quality of life with supervised exercise training in patients with type 2 diabetes in a randomised controlled trial: The Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study (IDES). Diabetologia. 2012;55(3):579–88.

Hajos TRS, et al. Psychometric and screening properties of the WHO-5 well-being index in adult outpatients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2013;30(2):e63–9.

Wadden TA. Impact of intensive lifestyle intervention on depression and health-related quality of life in type 2diabetes: The lookahead trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1544–53.

Mazhar K, et al. Severity of diabetic retinopathy and health-related quality of life: The Los Angeles Latino eye study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):649–55.

Kempf K, Kruse J, Martin S. ROSSO-in-praxi follow-up: Long-term effects of self-monitoring of blood glucose on weight, hemoglobin a1c, and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(1):59–64.

Hunger M, et al. Longitudinal changes in health-related quality of life in normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: results from the KORA S4/F4 cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(9):2515–20.

Sayah FA, Qiu W, Johnson JA. Health literacy and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(6):1487–94.

Thiel DM, et al. Physical activity and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: Results from a prospective cohort study. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(5):368–74.

Zhao H, et al. A longitudinal study on the association between diabetic foot disease and health-related quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(3):280-286.e1.

Lloyd CE, et al. Factors associated with the onset of major depressive disorder in adults with type 2 diabetes living in 12 different countries: Results from the INTERPRET-DD prospective study. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2020;29:e134.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the authors for their time and effort.

Funding

There was no funding obtained for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A. participated in all sections of this manuscript as well as prepared the master table and the flow diagram. K.H. and J.F. reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. All authors agreed to publish the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alzahrani, O., Fletcher, J.P. & Hitos, K. Quality of life and mental health measurements among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 21, 27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02111-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02111-3