Abstract

Background

Homelessness constitutes a traumatic period that adversely impacts health and quality of life outcomes. The potential mitigating effects of resilience on quality of life levels in people experiencing homelessness are underresearched. This study assesses the longitudinal associations between resilience and quality of life scores among adults experiencing homelessness and mental illness.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of longitudinal data collected over 6 years from participants (N = 575) of the At Home/Chez Soi study on Housing First, Toronto site. Repeatedly measured resilience scores are the primary exposure and repeatedly measured global quality of life scores and mental health-specific quality of life scores are the primary outcomes. Mixed effect models were used to assess the association between the exposures and the outcomes.

Results

The majority of the participants were men (69.2%) and were on average 40.4 (± 11.8) years old at baseline. The average resilience score ranged between 5.00 to 5.62 over 8 data collection points across the 6-year follow-up period. After adjusting for gender, age, ethno-racial background, Housing First intervention, physical and mental comorbidities, and lifetime homelessness, higher resilience scores were positively associated with higher Global quality of life (Adjusted-coefficient: 0.23, 95% CI 0.19–0.27) and mental health-related quality of life values (Adjusted-coefficient: 4.15, 95% CI 3.35–4.95).

Conclusion

In homeless adults with mental illness, higher resilience levels were positively associated with higher global and mental health related quality of life values. Further interventions and services aimed to enhance resilience mechanisms and strategies are warranted to enhance better mental health and quality of life outcomes of this population group.

Trial registration

At Home/Chez Soi trial was registered with ISRCTN, ISRCTN42520374. Registered 18 September 2009, http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN42520374.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Homelessness is a serious social and public health concern that affects thousands of people in both low-income and high-income countries [1]. It is a traumatic event that negatively affects health and well-being [2,3,4,5,6]. Those experiencing homelessness are often exposed to stressful conditions (e.g., lack of safety or a private space, perceived powerlessness and loss of social networks) commonly associated with shelter environments [2]. Additional traumatic and stressful experiences such as street victimisation, physical and sexual abuse, exposure to crime-related activities, and discrimination further compound the psychological effects of homelessness[4, 7, 8]. These traumatic events are often intertwined with trauma experienced prior to homelessness, such as adverse childhood experiences [9, 10], family dysfunction [11], or hazardous military service [12]. Exposure to trauma increases individual vulnerability to mental and substance use disorders, physical comorbidities, social disconnectedness, poor recovery outcomes and hopelessness [3, 4, 11, 13]. Indeed, traumatic experiences in this population are reflected in the high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental and substance use disorders [3, 4].

To overcome trauma, adversity, or stressful life changes, individuals have stress responses or adaptive mechanisms such as resilience [14,15,16,17]. Despite the lack of a universal definition of resilience, it is often referred to as biological, psychological and social processes or strategies that individuals have or adopt to resist or overcome life’s traumatic, stressful events and adversity [14,15,16,17]. Resilience is found to enhance individual adjustment or adaptation to new situations and allows people to bounce back from adversity or protect their mental health and wellbeing [14, 16,17,18,19,20]. In general, a high level of resilience has been found to improve mental health status, recovery (ability to function and live hopefully and meaningfully) and well-being outcomes [21, 22]. Similar positive effects of resilience are observed in adults affected by mental illness [18]. In socio-economically disadvantaged population groups, such as people experiencing homelessness, it has been found that more resilient individuals have higher levels of community functioning [23, 24] and social support [24], a higher percentage of days stably housed [24], and less suicidal ideation [25].

Despite their challenging social, housing and health conditions, some homeless people adopt resilience strategies to cope with their homeless state and life struggles. Some of these resilience strategies include use of affirmational statements, such as “stay strong and thankful,” “looking to live,” “hope to move forward,” “self-improvement,” “do not give up” [26], and remain “optimistic” and “confident” [27]. However, other less adaptive resilience strategies include negative feelings, emotional or psychological emptiness, pessimism and hopelessness [23, 26], which may hinder exits from homelessness and progress towards recovery. Resilience in homeless people is significantly negatively influenced by mental disorders (e.g., psychotic and depression disorders) [23, 28], which are frequently present in this population group.

Some researchers have studied the resilience process and outcomes in individuals experiencing homelessness, but there is still scant evidence on the association of resilience with overall and specific quality of life levels. Furthermore, the effects of resilience on well-being outcomes in homeless populations are often assessed using cross-sectional [23, 25] or qualitative methodological designs [26, 27]. To date, a handful of studies have explored this relationship over a short-term longitudinal period (e.g., ≤ 2 years)[24, 29]. The Toronto site of the At Home/Chez Soi (AH/CS) Housing First (HF) randomised trial collected six years of longitudinal data on quality of life and resilience measures among individuals with mental illness who were experiencing homelessness at the time of recruitment. The present study is a secondary analysis of these data. The objective of this study is to investigate the longitudinal associations of resilience levels with generic and mental health-related quality of life scores in adults who experience both homelessness and severe mental disorders.

Methods

Study population and design

The present study aimed analyses data from the Toronto site of the AH/CS study, which is part of the multi-site pragmatic randomised trial of HF in 5 cities across Canada (Toronto, Moncton, Montreal, Winnipeg and Vancouver) [30]. The Toronto AH/CS study design, population, tools and measures are published in detail elsewhere [31, 32]. Briefly, 575 participants were enrolled in the study between October 2009 and July 2011 and were followed up to March 2017 [32]. The primary participants’ inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) 18 years old or older; (2) homeless or precariously housed, with at least two episodes of absolute homelessness or one homelessness episode which lasted four or more weeks in the previous year; and (3) a diagnosed mental disorder with or without co-occurring substance or alcohol use disorder [31].

Participants were stratified according to their level of need for mental health services at the time of recruitment. High need participants were randomised to receive the HF intervention with assertive community treatment (ACT) and rent supplements or treatment as usual (TAU), which provided access to supportive housing and social and health services that were available in the community. Moderate need participants were randomised to either HF with intensive case management (ICM) plus rent supplements or to TAU. Detailed information on the specific level of needs criteria and the services provided for HF ACT, ICM treatment and TAU can be consulted in Hwang et al. [31].

The participants recruited for the Toronto AH/CS study site were initially followed for an average of 2 years (2009–2013) (phase 1) [32]. In 2014, they were re-enrolled in the study if willing to continue their participation (phase 2). A total of 414 of participants agreed to extend their participation for another two years and they were followed up to March 2017 [32]. The incompleteness of participants’ data over the follow-up period was due to participant attrition, missing interviews, missing item-responses, and low confidence in the participant questionnaire response assessed by the interviewer using an interviewer impression instrument [32].

Ethics approvals

The AH/CS study of the Toronto site received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael’s Hospital. At recruitment, all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. After an average of two years of follow-up, participants re-consented if they were willing to participate in the second phase of the study. The AH/CS study is registered with the International Standard Randomized Control Trial Number Register (ISRCTN42520374), http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN42520374

Study measures

Primary exposure

The overall resilience score, assessed using the abbreviate version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC2) [33, 34], is considered the primary exposure. The CD-RISC2, which included two items (“Able to adapt to change,” “Tend to bounce back after illness or hardship”) has been derived from the longer 25-item CD-RISC [33]. In previous studies, it has shown good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity, as well as high correlation with the overall 25-item CD-RISC score, being therefore, a good resilience indicator [34]. The CD-RISC2 was administered in face-to-face interviews at baseline, 12- and 24-months during phase 1 of the follow-up period, and at baseline, 6 and 18 months during the phase 2 of our study follow-up period. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the CD-RISC in our study population was 0.92, which is indicative of great reliability. The overall resilience score was calculated by adding the scores (0–4) from the two items, which produced a total score with a range between 0 and 8. Higher values indicated more resilience.

Quality of life outcomes

The main study outcomes are generic and mental health-specific quality of life scores. Generic quality of life was measured using the validated global 20-item of the Lehman’s 20-item QOL interview [35, 36], which measures QOL by assessing leisure, family and social relationships, finances, and safety domains. The abbreviated global 20-item was developed by Uttaro et al. using item-response theory and graded response modelling, with the purpose of reducing participant burden [36]. It retained similar internal consistency to that observed from the derived QOL dimensions scales of the Lehman’s 20-item QOL interview [36]. Therefore, it is a good single indictor to capture the overall essence of the subjective global quality of life. Further, it has previously used in study in homeless people [37] and in the context of the AH/CS study (data source of the present study) to assess changes in the QOL and the long-term effectiveness of HF on quality of life [32]. The Lehman’s 20-item QOL interview was administered in a face-to-face interview every six months during both phase 1 and phase 2 of the study follow-up [32]. The score for 20-item QOL ranges from 1 to 7-point order Likert scale, where the higher values indicate better overall quality of life.

Generic mental health related quality of life was assessed every six months only during phase 1 follow-up period using the EuroQol-5 vertical visual analogue scale (VAS) (0–100), which allows self-rated overall quality of life be linked to mental health status [38]. VAS values near 100 indicate high quality of life depending of their mental health. VAS format for measuring global QOL has been found to be valid, reliable and responsive as compared with QOL scores derived from other multi-item instruments[39], as it has showed moderate to high correlation with indicators of physical, psychological and social aspects of quality of life[39]. In our study population, assessing the mental health-related quality of life levels is critical as our participants had serious mental health disorders at baseline. Furthermore, previous studies carried out over phase 1 of the AH/CS study, find that participants continue to have high levels of severe mental health symptomatology over the two-years of follow-up [40,41,42]; therefore, it is likely that their mental health has continued to negatively affect their overall QOL over time. For the present study, the VAS was only analysed for phase 1 follow-up responses.

Covariates

The following baseline characteristics were used as both adjusting factors and covariates. Age, categorized as < 30, 30–39, 40–49, ≥ 50 years, was used to capture potential effect differences between younger and older age groups. Gender was dichotomized to include the categories men and women, as only seven participants self-identified as transgender or transsexual, which is too small sample to preform meaningful analyses. Ethno-racial and cultural identity background was categorized as Aboriginal, black, white and other. Year of lifetime homelessness was categorized as < 3 and ≥ 3 years, where 3 years or more indicated homelessness chronicity[31]. Mental comorbidity was grouped as having < 3 or ≥ 3 mental disorders as an indicator of higher mental health comorbidity. All participants in the present study had at least one mental health concern. Similarly, we categorized physical comorbidity as having < 3 or ≥ 3 chronic diseases, as our participants had on average 2.0 of these health conditions. As our study participants were part of an HF randomised trial [31, 32], the intervention group HF vs. TAU was also included as an adjusting variable and covariate.

Statistical analysis

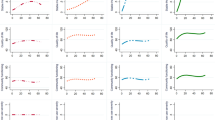

The participants’ main characteristics were described (frequency and percentage) in the overall study sample. The resilience scores (primary exposure) and main outcomes (overall disease and mental health-specific quality of life scores) over the phase 1 and phase 2 follow-up periods were plotted by HF intervention group, as this study was embedded within a HF RCT.

The associations between resilience and the outcomes of interest were assessed using linear mixed effect models to account for repeated measures over a follow-up period of up to six years. Compound symmetry structure was used and all models were adjusted for age, gender, ethno-racial and cultural identity background, year of lifetime homelessness, mental comorbidity, physical comorbidity, and HF intervention group.

All analyses were tested at 0.05 statistical significance level. The “nlme package” in the R statistical software version 3.5.0 was used to perform the analyses for the present study.

Results

The majority of study participants were men (68.36%). The mean age was 40.32 (SD 11.79) years, and majority of participants were from a black (34.55%) or white (35.27%) ethno-racial background (Table 1). 60.17% and 55.25% of participants had three or more mental disorders and physical chronic diseases, respectively. Slightly less than half of the participants (47.03%) had three or more years of lifetime duration of homelessness, and 52.35% received HF intervention, whereas 47.65% received TAU (Table 1).

The distribution of resilience scores, generic and mental health-specific quality of life scores over phases 1 and 2 of the follow-up period are presented according to HF treatment group in Fig. 1. The average scores for resilience slightly changed over the follow-up periods for HF and TAU participants, with values ranging between 5.00 to 5.21 over the six-year follow-up period. (Fig. 1a). The global quality of life scores ranged between 3.42 to 4.6 values over the six-year period (Fig. 1b), while the distribution of the mental-health quality of life scores over the two-year follow-up period ranged from 54.35 to 68.10 of the 100-maximum value (Fig. 1c).

The unadjusted and adjusted associations of resilience score with the quality of life outcomes are presented in Table 2. A one-point increase in resilience score was associated with higher values of global quality of life (Adjusted coefficient and 95% CI 0.23, 0.19–0.27) adjusting for gender, age, ethno-racial and cultural identity group, mental and physical comorbidities, lifetime duration of homelessness, and HF treatment group. A positive association between resilience levels and mental health-specific quality of life level was also observed, where one increased point in the resilience score was associated with an increase of 4.15 (95% CI: 3.35 to 4.95) points in participants’ mental health-related quality of life after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, health related comorbidities and HF intervention group (Table 2.)

Discussion

This longitudinal study of adults experiencing homelessness and mental illness identified that high levels of resilience were positively associated with greater global and mental quality of life scores. Among these associations, higher values were observed for the mental health-related quality of life, where one increased point in the resilience score was associated with an increase of 4.15 points in the mental health-specific quality of life score.

Resilience is individual quality that allows coping with stressful life experiences [14,15,16,17], including adversity surrounding homelessness [23, 26,27,28, 43] and mental illness [18]. In this study, participants’ resilience scores over the six-year follow-up period ranged between 5.01 to 5.63 points, over the 0–8 range of values. These scores are similar to those observed in non-homeless populations outside Northern American settings, using the same 2-item resilience scale [44, 45], but lower compared to scores in the general population within the US context, where resilience levels average 6.91 points [34]. This finding suggests that people with experiences of homelessness and serious mental disorders can leverage strategies to strengthen resilience and adversity while experiencing unstable housing.

Among the strategies that people leverage to overcome homelessness and its sequelae, some may promote their health and well-being. For example, individuals may seek instrumental support, socialize, engage in meaningful activities, and maintain hopefulness [26, 27, 46]. However, other strategies or behaviours used as adaptive mechanisms may have a negative impact on health and other outcomes. Among those maladaptive strategies are drug and alcohol use [27, 47] and engagement with criminal-related activities[48]. Thus, it is crucial to facilitate access to and provide social, psychological, emotional, and health support and services to boost this population’s resilience and to enhance other life dimensions, such as health, mental health, and quality of life. Our findings offer some promising insights in this little studied or understood area.

In our study population, we found that people with higher scores of resilience also had better global quality of life levels over the six-year follow-up period, as well as higher mental health-related quality of life values over the first two-years of follow-up. In the general population, quality of life and substance use recovery are influenced by a wide range of multidimensional factors[49]. These factors become more varied and complex in the context of housing instability, homelessness, and mental illness [37, 50,51,52,53,54]. Resilience is considered an important life and health protective factor [55], as it can help homeless people look forward to life in a hopeful way even when they face adversity and social barriers. Further, resilience can facilitate integration in communities, build family and social relationships and networks, and allow for participation in meaningful activities (e.g., work, spirituality, leisure, training-related activities) [23, 27]. All of this, in turn, could lead to improvements in quality of life for persons experiencing homelessness and mental health concerns.

A study carried out among 410 Dutch homeless persons [55] found that most of participants have at least one personal life goal for their near future, and among these goals, building resilience were among those aspects that participants’ were looking forward to [55]. It also found that higher levels of goal-related self-efficacy were positively associated with higher quality of life values [55]. Another study conducted with youth who experience homelessness used latent class analysis, found that a greater level of resilience acts as a protective factor which is associated with improved quality of life [29]. The existing evidence and findings from the present study support the positive and instrumental role of resilience in achieving greater quality of life levels among people with experiences of homelessness and mental illness.

The present study has some limitations. Resilience and the studied outcomes were measured contemporaneously over the follow-up period; therefore, we cannot exclude potential reverse associations. Mental health-related quality of life was only analysed in phase 1 of the AH/CS study; hence, the observed findings may have differed if this measure had been analysed over the entire six-year follow-up period. Further, using the VAS for assessing the mental health-related quality of life may only capture the effect of a specific mental health disorder (e.g., depression) rather than the effects of all aspects of mental health status, which influence quality of life [39]. It is also likely that due to potential physical, cognitive and mental impairment of some participants, the VAS rating could be susceptible to marking error; therefore, VAS scores may not be reflective of actual mental health quality of life levels and potential changes over time. Despite these limitations, existing evidence indicates that the VAS is a valid instrument to capture respondents’ perspectives on their quality of life [56]. It has good inter-rater reliability and test–retest reliability when compared with quality of life scores derived for multi-dimensional or multi-item instruments [39]. In the present study, measures of objective quality of life were not included. Therefore, the associations between resilience and specific objective quality of life indicators (e.g. income) may differ from those observed in the present paper, which assesses subjective quality of life. Yet, if a person perceived their quality of life as poor, it is going to negatively affect overall well-being, even if an objective tool states that they have the resources for a high quality of life. Further, this study assesses general and mental health related quality of life, rather than focusing on specific indicators (e.g., employment, social networks) or dimensions level; therefore, the relationship between individual quality of life indicators and resilience should be explored in future studies. Finally, the present study was embedded in a pragmatic randomised trial with people experiencing both homelessness and mental illness. Thus, the findings may not be generalisable to all homeless individuals or to other settings.

The present study has implications for practice and policy. Our findings revealed that people experiencing both homelessness and mental illness have moderate resilience levels, and these are positively associated with improvements in their global and mental health-related quality of life levels over time. Therefore, there is an opportunity to implement interventions to further enhance resilience and coping strategies that may have lasting impacts on mental health, substance use and quality of life. Finally, social and health providers working with homeless people could also incorporate resilience-based psychoeducation services [19], where specific skills and capabilities such as active problem-solving, cognitive reappraisal, guided-self-dialogue, social support and competence building, learned optimism, and stress management could be enhanced to help this population group grow their resilience and overcome trauma and distress [15, 19].

In conclusion, higher resilience levels are positively associated with higher long-term global and mental-health related quality of life values in homeless adults with mental illness. Further interventions and services aimed to enhance resilience mechanisms and strategies are warranted to enhance better mental health and quality of life outcomes of this population group.

Availability of data and material

The At Home/Chez Soi study dataset cannot be made publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the data and agreements and procedures governing the use of the dataset that were established by the study sponsor, the Mental Health Commission of Canada. However, anonymized participant data from the AH/CS study, as well as the specific dataset used in the present paper, can be made available to investigators who complete the following steps: (1) present a study proposal that has received approval from an independent research committee or research ethics board; (2) provide a data request for review by the AH/CS data access committee; (3) following approval of the request, execute a data-sharing agreement between the investigators and the AH/CS data custodians. Study proposals and data access requests should be sent to Evie Gogosis (Evie.Gogosis@unityhealth.to), research manager for the Toronto site of the AH/CS study, and to Dr. Stephen Hwang (Stephen.Hwang@unityhealth.to), co-principal investigator of the Toronto site of the AH/CS study.

Code availability

The statistical code used in this study could be required to the corresponding author. The request will be revised by the AH/CS research team before it can made available.

Abbreviations

- AH/CS:

-

At Home/Chez Soi

- ACT:

-

Assertive community treatment

- CD-RISC:

-

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HF:

-

Housing first

- ICM:

-

Intensive case management

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

- VAS:

-

Vertical visual analogue scale

References

Homeless World Cup Foundation. Global Homeless Statistics [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: https://homelessworldcup.org/homelessness-statistics/

Goodman L, Saxe L, Harvey M. Homelessness as psychological trauma: Broadening perspectives. Am Psychol. 1991;46:1219–25.

Whitbeck LB, Armenta BE, Gentzler KC. Homelessness-related traumatic events and PTSD among women experiencing episodes of homelessness in three U.S. Cities. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:355–60.

Deck SM, Platt PA. Homelessness is traumatic: abuse, victimization, and trauma histories of homeless men. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2015;24:1022–43.

Coates J, McKenzie-Mohr S. Out of the frying pan, into the fire: trauma in the lives of homeless youth prior to and during homelessness. J Sociol Soc Welf. 2011;37:65–96.

Duncan S, Oby S, Larkin H. Trauma and adversity in the lives of people experiencing homelessness. In: Larkin H, Aykanian ASC, editors. Homelessness Prev Interv Soc Work. Springer; 2019. p. 41–56.

Ellsworth JT. Street crime victimization among homeless adults: a review of the literature. Vict Offenders. 2019;14:96–118.

Mejia-Lancheros C, Lachaud J, Campo PO, Wiens K, Nisenbaum R, Wang R, et al. Trajectories and mental health-related predictors of perceived discrimination and stigma among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229385.

Roos LE, Mota N, Afifi TO, Katz LY, Distasio J, Sareen J. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and homelessness and the impact of Axis I and II disorders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:275–81.

Woodhall-Melnik J, Dunn JR, Svenson S, Patterson C, Matheson FI. Men’s experiences of early life trauma and pathways into long-term homelessness. Child Abus Negl Elsevier. 2018;80:216–25.

Padgett DK, Hawkins RL, Abrams C, Davis A. In their own words: Trauma and substance abuse in the lives of formerly homeless women with serious mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:461–7.

Montgomery AE, Cutuli JJ, Evans-Chase M, Treglia D, Culhane DP. Relationship among adverse childhood experiences, history of active military service, and adult outcomes: Homelessness, mental health, and physical health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:262–8.

Taylor KM, Sharpe L. homeless adults in Sydney. Arch Intern Med. 2008;42:206–13.

Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is resilience? An Integrative Review of the empirical literature. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:980–1000.

Averill LA, Averill CL, Kelmendi B, Abdallah CG, Southwick SM. Stress response modulation underlying the psychobiology of resilience. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Current Psychiatry Reports; 2018;20.

Bennett JM, Rohleder N, Sturmberg JP. Biopsychosocial approach to understanding resilience: stress habituation and where to intervene. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:1339–46.

Stainton A, Chisholm K, Kaiser N, Rosen M, Upthegrove R, Ruhrmann S, et al. Resilience as a multimodal dynamic process. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13:725–32.

Ayed N, Toner S, Priebe S. Conceptualizing resilience in adult mental health literature: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psychol Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 2019;92:299–341.

Horn SR, Charney DS, Feder A. Understanding resilience: new approaches for preventing and treating PTSD. Exp Neurol. 2016;284:119–32.

Cadet JL. Epigenetics of stress, addiction, and resilience: therapeutic implications. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:545–60.

Färber F, Rosendahl J. The association between resilience and mental health in the somatically Il. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:621–7.

Ungar M, Theron L. Resilience and mental health: how multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;0366:1–8.

Greenberg JM, Wynn JK, Lee J, Hellemann G, Gabrielian S, Green MF. Resilience in homeless veterans: clinical and cognitive correlates. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2019;42:314–22.

Durbin A, Nisenbaum R, Kopp B, O’Campo P, Hwang SW, Stergiopoulos V. Are resilience and perceived stress related to social support and housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness? Heal Soc Care Community. 2019;27:1053–62.

Cleverley K, Kidd SA. Resilience and suicidality among homeless youth. J Adolesc. 2011;34:1049–54.

Shankar S, Gogosis E, Palepu A, Gadermann AM, Hwang SW. “I Haven’t Given Up and I’m Not Gonna”: a phenomenographic exploration of resilience among individuals experiencing homelessness. Qual Health Res. 2019;29:1850–61.

Paul S, Corneau S, Boozary T, Stergiopoulos V. Coping and resilience among ethnoracial individuals experiencing homelessness and mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:189–97.

Perron JL, Cleverley K, Kidd SA. Resilience, loneliness, and psychological distress among homeless youth. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:226–9.

Altena AM, Beijersbergen MD, Vermunt JK, Wolf JRLM. Subgroups of Dutch homeless young adults based on risk- and protective factors for quality of life: results of a latent class analysis. Heal Soc Care Community. 2018;26:e587–97.

Goering PNPN, Streiner DLDL, Adair C, Aubry T, Barker J, Distasio J, et al. The at Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: A pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000323.

Hwang SW, Stergiopoulos V, O’Campo P, Gozdzik A. Ending homelessness among people with mental illness: the at Home/Chez Soi randomized trial of a Housing First intervention in Toronto. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:787.

Stergiopoulos V, Mejia-lancheros C, Nisenbaum R, Wang R, Lachaud J, Campo PO, et al. Long-term effects of rent supplements and mental health support services on housing and health outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness: extension study of the At Home/Chez Soi randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:915–25.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82.

Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JRT. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 2007;152:293–7.

Lehman A. Measures of quality of life among persons with severe and persistent mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:78–88.

Uttaro T, Lehman A. Graded response modeling of the Quality of Life Interview. Eval Program Plann. 1999;22:41–52.

Lam JA, Rosenheck RA. Correlates of improvement in quality of life among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:116–8.

The Euroqol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (New York). 1990;16:199–208.

De Boer AGEM, Van Lanschot JJB, Stalmeier PFM, Van Sandick JW, Hulscher JBF, De Haes JCJM, et al. Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? Qual Life Res. 2004;13:311–20.

Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, Misir V, Skosireva A, Sarang A, Connelly J, et al. The effectiveness of a Housing First adaptation for ethnic minority groups: Findings of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–11.

Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, Misir V, Skosireva A, Connelly J, Sarang A, et al. Effectiveness of housing first with intensive case management in an ethnically diverse sample of homeless adults with mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–21.

O’Campo P, Stergiopoulos V, Nir P, Levy M, Misir V, Chum A, et al. How did a Housing First intervention improve health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto? Two-year outcomes from a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010581.

Narayan AJ. Personal, dyadic, and contextual resilience in parents experiencing homelessness. Clin Psychol Rev Elsevier Ltd. 2015;36:56–69.

Ni MY, Li TK, Yu NX, Pang H, Chan BHY, Leung GM, et al. Normative data and psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) and the abbreviated version (CD-RISC2) among the general population in Hong Kong. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:111–6.

Rapacciuolo A, Perrone Filardi P, Cuomo R, Mauriello V, Quarto M, Kisslinger A, et al. The impact of social and cultural engagement and dieting on well-being and resilience in a group of residents in the metropolitan area of Naples. J Aging Res. 2016;2016:1–11.

Tozer K, Tzemis D, Amlani A, Coser L, Taylor D, Van Borek N, et al. Reorienting risk to resilience: Street-involved youth perspectives on preventing the transition to injection drug use. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–11.

Rudzinski K, McDonough P, Gartner R, Strike C. Is there room for resilience? A scoping review and critique of substance use literature and its utilization of the concept of resilience. Subst Abus Treat Prev Policy. 2017;12:1–35.

Ferguson KM, Bender K, Thompson SJ. Gender, coping strategies, homelessness stressors, and income generation among homeless young adults in three cities. Soc Sci Med. 2015;135:47–55.

Potter J, Cantarero R, Wood H. The multi-dimensional nature of predicting Quality of Life. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2012;50:781–90.

Gentil L, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, Dorvil H, Fleury MJ. Profiles of quality of life in a homeless population. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:1–10.

Garey L, Reitzel LR, Neisler J, Kendzor DE, Zvolensky MJ, Neighbors C, et al. Health-related Quality of Life among homeless smokers: risk and protective factors of latent class membership. Behav Med. 2019;45:40–51.

Pauly BB, Gray E, Perkin K, Chow C, Vallance K, Krysowaty B, et al. Finding safety: a pilot study of managed alcohol program participants’ perceptions of housing and quality of life. Harm Reduct J. 2016;13:1–11.

O’Brien KK, Schuttke A, Alhakeem A, Donnelly-Swift E, Keogh C, O’Carroll A, et al. Health, perceived quality of life and health services use among homeless illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:139–45.

Palepu A, Hubley AM, Russell LB, Gadermann AM, Chinni M. Quality of life themes in Canadian adults and street youth who are homeless or hard-to-house: A multi-site focus group study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:1–11.

van der Laan J, Boersma SN, van Straaten B, Rodenburg G, van de Mheen D, Wolf JRLM. Personal goals and factors related to QoL in Dutch homeless people: what is the role of goal-related self-efficacy? Heal Soc Care Community. 2017;25:1265–75.

EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-5L User Guide, 2019. The Netherlands; 2019.

Acknowledgements

We thank AH/CS study’s participants for their involvement, and the AH/CS project team, site coordinators, and service providers who have contributed to the design, implementation and follow-up of participants.

Funding

The Toronto site of the AH/CS study was funded by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (HSRF #259), and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR MOP-130405). The present study also received funding from St. Michael’s Hospital Research Training Centre Scholarship awarded (2019) to Dr Cilia Mejia-Lancheros. The funding institutions had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, nor in the preparation, revision, or approval of the present manuscript. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anna Durbin, Julia Woodhall-Melnik, Ri Wang, and Cilia Mejia-Lancheros conceptualized the study. Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, Julia Woodhall-Melnik, and Ri Wang were responsible for the methodological approach of the study. Ri Wang carried out the statistical analysis and prepared the findings’ visualisations. Cilia Mejia-Lancheros carried out first interpretation of the study findings and wrote the first manuscript version. Julia Woodhall-Melnik, Anna Durbin, Ri Wang contributed to the validation and interpretation of the findings and critical revision and editing the first manuscript version. Vicky Stergiopoulos and Stephen W. Hwang made substantive intellectual contributions in the interpretation of the findings and revision of the final version of the manuscript. Vicky Stergiopoulos and Stephen W. Hwang are also the co-principal investigators of the Toronto site of the AH/CS study. All co-authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscripts and are accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved final manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Toronto site AH/CS study (phase 1 and phase 2) has received ethics approval (REB#: 09–208) from the Research Ethics Board of the St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mejia-Lancheros, C., Woodhall-Melnik, J., Wang, R. et al. Associations of resilience with quality of life levels in adults experiencing homelessness and mental illness: a longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01713-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01713-z