Abstract

Objective

Quality of life (QoL) is one major outcome parameter in the care for people with dementia (PwD); however, their assessment is lacking a gold standard. The purpose of this study was to evaluate potential factors associated with nurse-rated quality of life of PwD in nursing homes in Berlin, Germany.

Method

An explorative cross-sectional study was performed in five nursing homes to evaluate QoL. Nurses rated the QoL for all residents with dementia by completing two different standardised assessments (ADRQL, QUALIDEM). Potential associated factors were evaluated concerning resident and nurse related factors. A fixed-effects models of analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) was used to analyse effects of assumed associated factors of the major outcome parameters ADRQL and QUALIDEM. Associated factors were severity of dementia (GDS), challenging behaviour (CMAI), and other characteristics. Regarding the nurses, burnout (MBI), satisfaction with life (SWLS), attitude (ADQ) and empathy toward residents (JSPE), as well as circumstances of the ratings and days worked in advance of the ratings were assessed.

Results

In total, 133 PwD and 88 nurses were included. Overall, the ratings show moderate to high QoL in every subscale independent of the instrument used. Assumed confounders relevantly influenced 14 out of 17 ratings. Predominantly, residents’ challenging behaviour, nurses’ burnout and satisfaction with life as well as the circumstances of the ratings are significant and clinically relevant associated factors.

Conclusion

Assessing QoL of PwD is acknowledged as a central component of health care and health care research. In later stages of dementia, proxy-reported information obtained from quality of life questionnaires is and will continue to be essential in this research. However, methodological issues that underline this research - matters of measurement and instrument validity - must receive more attention. Associated factors in proxy-ratings have to be routinely assessed in order to get more valid and comparable estimates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, the number of persons with dementia (PwD) is increasing [1]. Therefore, care of PwD is challenging and becomes a focal point of interest. Although most PwD are community-dwelling and cared for by relatives and friends, dementia is one major reason for relocation into a nursing home [2]. Various studies have aimed to improve the care provision in those settings. To evaluate the impact of an intervention, quality of life (QoL) is considered one of the main parameters; it includes objective and subjective aspects of PwD [3],[4].

Quality of life ratings

The evaluation of QoL of PwD is associated with various problems [5], especially because there is no ‘gold standard’ [6]. However, the evaluation of QoL is possible in self and/or proxy-ratings [7]. In addition, due to the subjective aspects of the concept of QoL, self-rating scales are considered the best way to evaluate QoL [8] but in longitudinal interventional studies it is unclear whether changes in QoL are caused by the progression of the dementia and associated disorders or actually by the interventional program. Moreover, in a population with severe dementia, PwD are frequently unable to understand the questions or even remember the situation about which they are asked [9]. Therefore, especially in a population with severe dementia, proxy-ratings (e.g., by nurses) are the method of choice and reduce the number of missing values [10]. Typically, dementia-specific QoL questionnaires show a sufficient reliability, e.g., inter-rater reliability [7]. However, associated factors reliability have yet to be investigated. In addition, proxy-ratings are associated with various unknown factors. This leads to a weak level of agreement between self- and proxy-ratings [10],[11]. Few studies report predictors of a higher level of agreement between PwD and family members [12],[13]. Studies investigating the ratings of PwD and nurses determined that being the responsible nurse [10] and staff age [11] are factors which improve the general level of agreement.

In various studies, effects of an intervention on proxy-rated QoL were found [14],[15]. Other studies did not find convincing effects [16],[17]. In these examples, the results are discussed only in light of the research questions. However, it is unclear if the ratings themselves are influenced by factors other than the intervention and it is unknown which factors might influence nurse-ratings basically.

A deeper insight into associated factors of proxy-ratings of QoL is required. The investigation of ‘factors that affect both patient and caregiver ratings […] of QoL’ [18] is recommended. Those factors can be characteristics of nurses (e.g., burnout, attitude toward PwD) but also circumstances of the rating (e.g., at beginning of the shift, after holiday). To optimise the interpretation of interventional results, a valid QoL evaluation with individuals who have a severe level of dementia, is necessary. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate:

variability of nurses rated QoL of PwD in institutional long-term care facilities in Germany

PwD and nurse related factors associated with nurses rated QoL

Method

Sample and setting

Five nursing homes with ten wards for PwD participated in the study. All residents with a medical diagnosis of dementia and all nurses, either registered nurses or nursing assistances, working predominantly in a participating ward were included in the study.

Procedure

In an explorative cross-sectional study, written study information was sent to heads of ten randomly selected nursing homes in Berlin, Germany, with the request to participate in the study. After four weeks, all nursing homes were contacted by phone. Primary nurses of each resident provided socio-demographic (age, sex) and further resident related characteristics (e.g., severity of dementia, need-based behaviour) on a written questionnaire. Afterwards each nurse received a written standardised questionnaire to rate the QoL of each resident in their ward. In addition, nurses provided information on their own socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., sex, age, time of being in the ward, being the responsible nurse). Additionally, nurses rated their own attitude towards PwD, empathy, satisfaction with life, burnout, days worked in advance of the ratings, and circumstances (e.g., before starting the shift) of the ratings.

Quality of life measurements

The main focus within this article is measuring quality of life of PwD in nursing homes. To avoid instrument-related effects, two different proxy-rated QoL-instruments were applied as primary measurements. However, only two proxy-rated quality of life instruments, focusing on institutionalised people with all stages of dementia, the ADRQL and the QUALIDEM, are available in a validated German version.

Alzheimer’s Disease Related Quality of Life (ADRQL)

The Alzheimer’s Disease Related Quality of Life (ADRQL) [19] assessment consists of 47 items concerning observable behaviour within the last two weeks. Their occurrence can be ‘agreed’ or ‘disagreed’ upon. The authors defined an item-specific value to weight the ratings. A relative global score and five relative scores for subscales (‘social interaction’; ‘awareness of self’; ‘enjoyment of activities’; ‘feelings and mood’; ‘response to surroundings’) were calculated. Due to relative score calculations, an imputation of missing values is not necessary. A higher score (0-100) indicates higher QoL. The German version of the ADRQL shows sufficient to good reliability. The validity was proofed using discriminant and convergent, as well as construct, validity by confirmatory factor analysis [20].

QUALIDEM

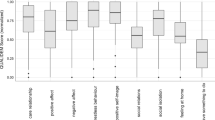

The QUALIDEM [21],[22] is a 37-item instrument for PwD. It includes nine subscales (‘care relationship’; ‘positive affect’; ‘negative affect’; ‘restless tense behaviour’; ‘positive self-image’; ‘social relations’; ‘social isolation’; ‘feeling at home’; ‘having something to do’) for mild to moderate dementia. For people with severe dementia, the number of items is 18 and only six subscales (excluded are: ‘positive self-image’; ‘feeling at home’; ‘having something to do’) are calculated. Various behaviours of the past week were rated from 0 = ‘never’ to 3 = ‘frequently’ or vice versa. The expectation-maximisation algorithm was used to impute missing values. A higher sum score indicates higher QoL. The global QoL score was calculated by summing up all items, without any weighting. To increase comparability, scores of all subscales and the global scores were linearly adapted to a scale from 0-100 (per scale: Σitemi × 100 / 3 × itemi). The German QUALIDEM versions show a weak inter-rater reliability [23]. The validity was again proofed using discriminant and convergent, as well as construct, validity by confirmatory factor analysis [20].

Measurements of associated factors

PwD-related measurements included the severity of dementia, using the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) [24]. A higher stage indicates a more severe level of dementia. Challenging behaviour of residents was assessed by using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) [25]. Responsible nurses rated 29 behaviours on a seven point Likert-scale (from ‘never’ to ‘a few times in an hour’). The analysis indicated whether aggressive behaviour, physically nonaggressive behaviour or verbally agitated behaviour occurred. Further nurse-related outcomes included burnout as evaluated by using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [26]. A 25 item questionnaire with ratings from ‘never’ to ‘frequently’ form three subscales: ‘emotional exhaustion (EE)’, ‘depersonalization (D)’, and ‘personal accomplishment (PA)’. For each subscale mild, moderate or severe burden of nurses is assessed. The attitude towards PwD was evaluated by applying the Approach to Dementia Questionnaire (ADQ) [27]. Nurses had to rate 19 statements on a five-point Likert-scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. These ratings result in a global sum score (19-95 points) and the domains ‘person centeredness’ (11-55) and ‘hope’ (8-40). Higher scores indicate a more positive attitude towards PwD. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) [28], a questionnaire with 20 statements each rated on a seven-point Likert-scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, was used to assess the empathy of nurses. A higher sum score (20-140 points) indicates higher empathy. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [29] was used to evaluate nurses’ satisfaction with life. Five aspects were rated on a 7-point Likert-scale (ranging from ‘extremely unsatisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’). A global sum score was calculated, higher scores (5-35) indicate higher satisfaction with life. Additionally, basic characteristics of residents (e.g., age, sex) and nurses (e.g., age, sex, being the responsible nurse, being a registered nurse) were surveyed.

All associated variables show good psychometric properties for applied versions [24]-[29].

Statistical analysis

Basic characteristics of residents and nurses were described using descriptive statistics. Correlations among metric/ordinal variables were examined by Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlations. Fixed-effects models of analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) were used to investigate effects of assumed categorical and continuous associated factors of the major outcome parameters ADRQL and QUALIDEM (total score and subscales for each). These models were adjusted for confounding factors such as severity of dementia (GDS; levels ≤4, 5, 6, 7), occurrence of at least one challenging behaviour (CMAI), residents’ sex, nurses’ sex, being the responsible nurse (yes/no), being a registered nurse (yes/no), burnout (‘MBI-EE’, ‘MBI-PA’, ‘MBI-D’), circumstances of ratings, time being on the ward (nurses), attitude (ADQ total score), empathy (JSPE), satisfaction with life (SWLS) and days worked in advanced of the ratings (nurses). Interactions between confounding variables were not modelled because of the small sample size. Statistical model assumptions of normal distribution and multicollinearity for variables were examined before conducting further analyses. Two-sided significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Due to multiple testing, Bonferroni-correction was applied for ADRQL and QUALIDEM analyses (total score and subscales; α = 0.003). All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS® (v21.0).

The study was conducted in line with German law and the declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. The Ethics Committee of the German Society of Nursing Sciences approved the study protocol.

Results

In total, five nursing homes with ten wards participated in this study. For all eligible residents (n = 133) data was collected. The number of participating nurses was 88, this corresponds to a response rate of 86.6%. In Table 1, characteristics of residents and nurses are shown. No significant correlations between residents’ measurements appeared in the analyses and all measurements of possible confounding factors were included in the analyses of (co-)variance. Regarding nurses’ characteristics, the only significant correlations were found between ADQ total score and ADQ subscales ‘person centeredness’ (r = 0.870 [95% CI: 0.758; 0.982], p < 0.001) and ‘hope’ (r = 0.792 [95% CI: 0.653; 0.930], p < 0.001), all possible confounding factors were included in the analyses of (co-)variance.

Quality of life

A total of 1,482 QoL ratings for ADRQL and QUALIDEM (each) could be included in further analyses. On average for each resident QoL was rated 11 times, by using the ADQRL and QUALIDEM. Each nurse rated QoL16.8 times. Within these ratings there was 3.7% missing items for the ADRQL and 4.1% missing values for the QUALIDEM.

The circumstances of ratings are comparable between both instruments. Predominantly, ratings are done during the shift (ADRQL: 33.5%; QUALIDEM: 33.4%) or shortly afterwards (ADRQL: 29.4%; QUALIDEM: 29.2%). Rarely, QoL ratings are done in advance of a shift (ADRQL: 12.4%; QUALIDEM: 13.3%). All other ratings are done during leisure time. Before performing ADRQL and QUALIDEM ratings, nurses worked on average 3.8 (SD 2.5; min: 0; max: 6) days.

The average QoL scores are displayed in Table 2. All scores indicate a moderate to high QoL of residents. The ADRQL and QUALIDEM scores are comparable; however, the standard deviations (ADRQL: 17.5 up to 22.9; QUALDEM: 18.7 up to 29.9) indicate heterogeneous ratings.

Associated factors of the ADRQL

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the ANCOVA-analyses for the ADRQL. Regarding the corrected alpha-level, all six models show significant (all ANCOVA, p < 0.003) results with a proportion of explained variance up to one quarter (R2 up to 0.266). Altogether, ten associated factors were identified. Variables associated with each of the five scores are: severity of dementia (GDS), nurses’ satisfaction with life (SWLS) (‘total score’, ‘social interaction’, ‘awareness of self’, ‘moods and feeling’, ‘enjoyment of activities’) and circumstances of ratings (‘total score’, ‘social interaction’, ‘awareness of self’, ‘moods and feeling’, ‘response to surroundings’). Three scores (‘total score’, ‘moods and feeling’, ‘response to surroundings’) are influenced by the occurrence of challenging behaviour (CMAI) and the time nurses are already in the ward. Higher burnout of nurses (‘total score’, ‘moods and feelings’) and the number of days nurses worked in advance of the ratings (‘awareness of self’, ‘response to surrounding’) influence two scores. The direction of influence is displayed in Table 4.

Associated factors of the QUALIDEM

Five out of the nine subscales and the total score of the QUALIDEM could significantly be explained by covariance analyses (Table 5). The explained proportion of variance is again up 53.2% (R2 = 0.532). Five subscales (‘total score’, ‘care relationship’, ‘positive affect’, ‘restless tense behaviour’, and ‘social isolation’) result in higher QoL in the case of absence of challenging behaviours or a higher burden for nurses (MBI) or nurses’ higher satisfaction with life (SWLS). Ratings during the shift are associated with lower QoL in three QUALIDEM subscales (‘positive affect’, ‘negative affect’, and ‘restless tense behaviour’). Two subscales (‘care relationship’ and ‘restless tense behaviour’) result in higher QoL in the case of lower severity of dementia (See Table 6).

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify possible associated factores of nurse rated QoL of PwD in German nursing homes. By identifying such associated factors, the performance of QoL proxy-ratings can be improved. Taking these associated factors into account, ratings are more reliable and most notably more comparable.

The mean age, gender distribution as well as severity of dementia indicates a typical German and international nursing home population [15],[17],[30]. In addition, characteristics (age, proportion of female, etc.) of the included nurses are comparable to those of the larger nursing exit study in various European countries [17],[31]. Thus, we can conclude that we have no sample bias and the results of the study are valid from this point of view.

Identification of associated factors of proxy-rated QoL

We found various factors associated the proxy-ratings. First, the resident related factors are discussed. The data analyses show, that 13 out of 16 QoL scores (subscales and total scores) were significantly influenced by the assumed factors. Residents’ sex only influences the subscale negative affect of the instrument QUALIDEM. This is largely in line with the results of a previous study, which concludes that QoL is independent from sex [5],[32]. However, occurrence of challenging behaviour is associated with residents’ lower QoL in the present as well as in previous studies [5],[32]. In addition, the severity of dementia effects the proxy-ratings. Lower severity is described to be associated with higher QoL, as it is in the present study. Due to the presence of challenging behaviour and that the level of severity of dementia may change over time [16], longitudinal studies have to consider these aspects as possible confounders in order to adjust analyses. If not accounted for, possible effects of care provision as well as interventional effects might be hidden and no clear conclusions could be drawn.

In addition to resident characteristics we found various nurse related characteristics that influence the proxy-rated QoL of nursing home residents with dementia. Due to the lack of similar studies, a critical discussion of identified associated factors is difficult, particularly, caregiver burnout as lower burden, frequently results in higher QoL-ratings. This might result from the fact that nurses with a higher burden expect the person with dementia to be burdened as well and therefore assume a low QoL. However, this issue needs to be clarified in future research projects. Generally, the literature has described that nurses in German institutional care settings frequently suffer from burnout [33]. This has to be taken into account, when using nurses as surrogates for residents in any study.

The circumstances of proxy-ratings are relevant associated factors as well. In various studies, the time at which proxy-ratings are completed is not described. Based on the present results, different circumstances might lead to different ratings, which are also clinically relevant (β up to 18.8).

Limitations

The study was performed as a single centre study using a convenience sample consisting of residents and nurses from Berlin, Germany. Although we do not believe we had a sampling bias, this may influence the results. In addition, about 14% of nurses did not participate in our study. This may limit our results. The achieved explanation of variance throughout the co-variance analyses is not very high, thus further associated factors might exist in addition to those identified in the present study, e.g., functional abilities or depression of residents. A larger sample with a more comprehensive profile of nurses may address this issue.

Conclusion

Assessing QoL of PwD is acknowledged as a central component of health care and health care research. In later stages of dementia, proxy-reported information obtained from quality of life questionnaires is and will continue to be essential. However, methodological issues that underline this research - matters of measurement and instrument validity - have to receive more attention. Associated factors in proxy-ratings have to be routinely assessed in order to get more valid and comparable estimates. Especially in longitudinal studies, changes in QoL over time can be influenced by factors other than the primary goals e.g., the evaluation of an intervention.

References

Prince M, Prina M, Guerchet M: World Alzheimer Report 2013 - Journey of Caring. Alzheimer's Disease International, London; 2013.

Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König H-H, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG: Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2010, 39: 31–38. 10.1093/ageing/afp202

Barofsky I: Can quality or quality-of-life be defined? Qual Life Res 2012, 21: 625–631. 10.1007/s11136-011-9961-0

Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods R, Verhey F, Chattat R, de Vugt M, Mountain G, O’Connell M, Harrison J, Vasse E, Dröes RM, Orrell M: INTERDEM group: A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health 2008, 12: 14–29. 10.1080/13607860801919850

Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, Alvir J, Treglia M, Schwam EM, del Valle M: What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009, 24: 15–24. 10.1002/gps.2090

Edelman P, Fulton B, Kuhn D, Chang C-H: A Comparison of three methods of measuring dementia-specific quality of life: perspectives of residents, staff, and observers. Gerontologist 2005, 45: 27–36. 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.27

Gräske J, Fischer T, Kuhlmey A, Wolf-Ostermann K: Dementia-specific quality of life instruments and their appropriateness in shared-housing arrangements - a literature study. Geriatr Nurs 2012, 33: 204–216. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.01.001

Trigg R, Watts S, Jones R, Tod A: Predictors of quality of life ratings from persons with dementia: the role of insight. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011, 26: 83–91. 10.1002/gps.2494

Streiner DL, Norman GR: Health Measurements Scales - a Practical Guide to their Development and Use. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 2003.

Gräske J, Fischer T, Kuhlmey A, Wolf-Ostermann K: Quality of life in dementia care – differences in quality of life measurements performed by residents with dementia and by nursing staff. Aging Ment Health 2012, 16: 818–827. 10.1080/13607863.2012.667782

Spector A, Orrell M: Quality of Life (QoL) in dementia: a comparison of the perceptions of people with dementia and care staff in residential homes. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006, 20: 160–165. 10.1097/00002093-200607000-00007

Schulz R, Cook TB, Beach SR, Lingler JH, Martire LM, Monin JK, Czaja SJ: Magnitude and causes of bias among family caregivers rating Alzheimer disease patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013, 21: 14–25. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.002

Pfeifer L, Drobetz R, Fankhauser S, Mortby ME, Maercker A, Forstmeier S: Caregiver rating bias in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease: impact of caregiver burden and depression on dyadic rating discrepancy across domains. Int Psychogeriatr 2013, 25: 1345–1355. 10.1017/S1041610213000562

Nordgren L, Engström G: Animal-assisted intervention in dementia: effects on quality of life. Clin Nurs Res 2014, 23: 7–19. 10.1177/1054773813492546

Crespo M, Hornillos C, Gómez MM: Dementia special care units: a comparison with standard units regarding residents’ profile and care features. Int Psychogeriatr 2013, 25: 2023–2031. 10.1017/S1041610213001439

Wolf-Ostermann K, Worch A, Fischer T, Wulff I, Gräske J: Health outcomes and quality of life of residents of shared-housing arrangements compared to residents of special care units - results of the Berlin DeWeGE-study. J Clin Nurs 2012, 21: 3047–3060. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04305.x

Verbeek H, Zwakhalen SMG, Van Rossum E, Ambergen T, Kempen GIJM, Hamers JPH: Dementia care redesigned: effects of small-scale living facilities on residents, their family caregivers, and staff. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010, 11: 662–670. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.08.001

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L: Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med 2002, 64: 510–519. 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016

Rabins PV, Kasper JD, Kleinman L, Black BS, Patrick DL: Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer disease. J Ment Health 1999, 5: 33–48.

Gräske J, Verbeek H, Gellert P, Fischer T, Kuhlmey A, Wolf-Ostermann K: How to measure quality of life in shared-housing arrangements? A comparison of dementia-specific instruments. Qual Life Res 2014, 23: 549–559. 10.1007/s11136-013-0504-8

Ettema TP, Dröes R-M, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW: QUALIDEM: development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument: scalability, reliability and internal structure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007, 22: 549–556. 10.1002/gps.1713

Ettema TP, Dröes R-M, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW: QUALIDEM: development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument – validation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007, 22: 424–430. 10.1002/gps.1692

Dichter MN, Schwab CGG, Meyer G, Bartholomeyczik S, Dortmann O, Halek M: Measuring the quality of life in mild to very severe dementia: testing the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of the German version of the QUALIDEM. Int Psychogeriatr 2014, 26: 825–836. 10.1017/S1041610214000052

Reisberg B, Ferris S, de Leon M, Crook T: The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1982, 139: 1136–1139. 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136

Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS: A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol 1989, 44: M77-M84. 10.1093/geronj/44.3.M77

Büssing A, Perrar KM: Die Messung von Burnout. Untersuchung einer Deutschen Fassung des Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D). [Measurement of burnout. Investigation of a German version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D)]. Diagnostica 1992, 38: 328–353.

Macdonald AJD, Woods RT: Attitudes to dementia and dementia care held by nursing staff in U.K. “non-EMI” care homes: what difference do they make? Int Psychogeriatr 2005, 17: 383–391. 10.1017/S104161020500150X

Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Cohen MJM, Gonnella JS, Erdmann JB, Veloski J, Magee M: The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas 2001, 61: 349–365. 10.1177/00131640121971158

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S: The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985, 49: 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dichter MN, Dortmann O, Halek M, Meyer G, Holle D, Nordheim J, Bartholomeyczik S: Scalability and internal consistency of the German version of the dementia-specific quality of life instrument QUALIDEM in nursing homes - a secondary data analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013, 11: 1–13. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-91

Li J, Galatsch M, Siegrist J, Möller BH, Hasselhorn HM: Reward frustration at work and intention to leave the nursing profession - prospective results from the European longitudinal NEXT study. Int J Nurs Stud 2011, 48: 628–635. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.011

Beerens HC, Zwakhalen SMG, Verbeek H, Ruwaard D, Hamers JPH: Factors associated with quality of life of people with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013, 50: 1259–1270. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.005

Wolf-Ostermann K, Gräske J: Psychische Belastungen in der stationären Langzeitpflege [Psychological Burden in Institutional Long-term Care]. Public Health Forum 2008, 16: 15.e11–15.e13. 10.1016/j.phf.2008.11.010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

Study design: KWO, JG. Data collection: SM, JG, KWO. Data analysis: JG, SM, KWO. Manuscript preparation: JG, KWO, SM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gräske, J., Meyer, S. & Wolf-Ostermann, K. Quality of life ratings in dementia care – a cross-sectional study to identify factors associated with proxy-ratings. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12, 177 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0177-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0177-1