Abstract

Background

People who smoke crack cocaine experience a wide variety of health-related issues. However, public health programming designed for this population is limited, particularly in comparison with programming for people who inject drugs. Canadian best practice recommendations encourage needle and syringe programs (NSPs) to provide education about safer crack cocaine smoking practices, distribute safer smoking equipment, and provide options for safer disposal of used equipment.

Methods

We conducted an online survey of NSP managers across Canada to estimate the proportions of NSPs that provide education and distribute safer smoking equipment to people who smoke crack cocaine. We also assessed change in pipe distribution practices between 2008 and 2015 in the province of Ontario.

Results

Analysis of data from 80 programs showed that the majority (0.76) provided education to clients on reducing risks associated with sharing crack cocaine smoking equipment and about when to replace smoking equipment (0.78). The majority (0.64) also distributed safer crack cocaine smoking equipment and over half of these programs (0.55) had done so for less than 5 years. Among programs that distributed pipes, 0.92 distributed the recommended heat-resistant Pyrex and/or borosilicate glass pipes. Only 0.50 of our full sample reported that their program provides clients with containers for safer disposal of used smoking equipment. The most common reasons for not distributing safer smoking equipment were not enough funding (0.32) and lack of client demand (0.25). Ontario-specific sub-analyses showed a significant increase in the proportion of programs distributing pipes in Ontario from 0.15 (2008) to 0.71 (2015).

Conclusions

Our findings point to important efforts by Canadian NSPs to reduce harm among people who smoke crack cocaine through provision of education and equipment, but there are still limits that could be addressed. Our study can provide guidance for future cross-jurisdiction studies to describe relationships involving harm reduction programs and provision of safer crack cocaine smoking education and equipment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although the harm reduction philosophy that has moved forward in Canada, and North America more broadly, is inclusive of people who consume a wide spectrum of psychoactive substances, actual programming has been more focused on people who inject drugs. This is concerning from a public health perspective because in Canada crack cocaine use is common among street-based people who use drugs [1–3]. People who smoke crack cocaine report experiencing oral sores, cuts, and burns that are connected to the use of improvised crack pipes fashioned out of hazardous glass and metal materials [4, 5], and such injuries may facilitate infectious disease transmission when pipes are shared among users [6, 7]. Pipe sharing is also commonly reported, especially when pipes are difficult to obtain [8–10]. Indeed, evidence shows elevated rates of hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as HIV and other infectious diseases, among people who smoke crack cocaine [11–15].

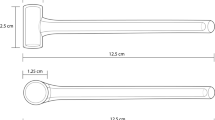

There are likely various, and some convergent, reasons why harm reduction programming for people who smoke crack cocaine has lagged behind programming developed for people who inject drugs. Injection drug use has long been considered the riskiest form of drug use in terms of potential health-related risks and as such public health authorities have prioritized services, especially HIV prevention services, for people who inject drugs (e.g., [16]). Nonetheless, although people who use illicit drugs in general are a socially marginalized group, people who smoke crack cocaine often exhibit pronounced marginalization characterized by, for example, poverty, unstable housing or homelessness, and elevated rates of encounters with the criminal justice system (e.g., [1, 17–19]). The establishment of greater services for this drug-using population has relied on additional advocacy efforts. Harm reduction advocates in Toronto and Vancouver were among the first groups in Canada to recommend and begin distribution of safer smoking equipment to engage people who smoke crack cocaine in programming [20, 21]. However, implementation of policies and interventions designed for crack cocaine users has also been hindered and delayed by questions about the legality of the distribution of safer smoking equipment and related opposition from police (cf. [19, 22–26]). In an effort to promote programming that addresses high rates of HCV among people who smoke crack cocaine, Canadian best practice recommendations encourage needle and syringe programs (NSPs) and other harm reduction programs to provide education on safer crack cocaine smoking practices and use of smoking equipment; distribute safer smoking equipment (i.e., Pyrex and/or borosilicate glass pipes or “stems”, mouthpieces, screens, and push sticks); and provide options for safer disposal of used equipment [27]. See Fig. 1 for a snapshot of the complete set of these best practices pertaining to safer crack cocaine use. These evidence-based guidelines for safer crack cocaine smoking education and equipment distribution were developed by a national, multi-stakeholder team (for a description of the best practices team formation, composition, and collaboration, see [28]).

As part of a national-in-scope evaluation of NSP practices and policies, the first of its kind that we are aware of in Canada, we conducted a survey of program managers to estimate the proportions of NSPs providing education and distributing safer smoking equipment to people who smoke crack cocaine. For the province of Ontario, we used previously collected survey data [25] to assess if there had been a change in the distribution of safer smoking equipment over time.

Methods

Managers of NSPs across Canada were invited to participate in an online survey examining program policies and uptake of best practices. Eligible programs included those operated by a public health organization or other agency contracted by their local health unit to provide needle/syringe distribution in any province or territory. We focused on these “core” programs associated with public health units and did not attempt to sample “satellite” NSP services (see [25]). To expand their reach, core NSPs often engage other organizations to be satellite sites that can also offer NSP services. Trying to sample all NSPs including satellite sites would have been a time-consuming effort and one that might not have added much value as core NSPs often provide their local satellite services with the necessary training (including policies and procedures to follow), supplies, and support (see again [25]). As there is no central registry of all NSPs in Canada, we created an email address list using three approaches. First, we knew from best practices research team members that three provinces (Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia) kept their own comprehensive and up-to-date lists of all NSPs (including program manager email addresses) for their respective regions. We obtained these lists for Quebec and Ontario. An official from the western province of British Columbia opted out of providing their email list stating that the burden of participation was too great for local NSP managers who were at that time implementing new overdose prevention programming. We did not have the time and resources necessary to contact all public health units in British Columbia and then follow up with all NSPs in that province to obtain the requisite email addresses. For the remaining provinces where, in some cases, there was a small number of programs and local managers knew each other, we asked the regional representative on the best practices team to provide email contact information for NSP managers in their province. Lastly, for the territories, the first author contacted local harm reduction representatives and a territorial ministry of health to identify NSP managers in those regions. The northernmost territory, Nunavut, did not have an NSP. Using these three approaches, we believe that we captured the email addresses for managers of all operational core NSPs in Canada, with the exception of NSPs in British Columbia.

To encourage survey participation, we modified a method by Dillman et al. [29] by asking team members who were involved in harm reduction policy and/or service provision in their regions to send to their local NSP managers an initial email “alert” to introduce the study and advise of upcoming invitations to participate. One to 2 weeks after these alerts were sent, the first author sent formal email invitations to potential participants in each province and territory; these invitations included a study information sheet with consent form and a link to the survey. Two weeks after these invitations, potential participants were sent the first email reminder about the survey. Two weeks after these reminders, we emailed potential participants a final reminder about completing the survey. To provide incentive to participate in the online survey, we offered to all potential participants an option to enter a draw to win for their program one of 20 gift cards worth $100CAD for a well-known coffee shop chain. Study recruitment was staggered and the survey was open to participants from April 9 to August 4, 2015.

Participants were asked questions (in Yes/No, multiple choice, Likert scale, and open-ended formats) about their program characteristics, distribution of harm reduction materials, including safer crack cocaine smoking equipment, and other key topics identified in the best practice recommendations [27, 30]. The questionnaire was developed for an online platform, FluidSurveys, and was offered in English and French. Please see Additional file 1 that contains English online survey text that is relevant to the findings we report in this article. Before launching data collection, we pilot tested the online survey with five program managers from different provinces and modified some questions as per their feedback. The University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (REB) approved this study.

Data were downloaded, managed, and analyzed using SPSS (version 24). Specifically, we report frequency distributions and bivariate statistics to characterize the proportion of programs offering safer crack cocaine smoking education and equipment distribution by NSPs. In addition, using data from an earlier study that used the same online survey methods for Ontario [25], we compared the proportion of programs in that province that distributed pipes in 2008 versus 2015. Similar data were not available for the other provinces or territories.

Results

Sample characteristics

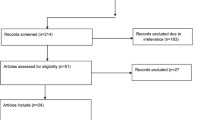

We invited 125 NSP managers from across Canada to complete the online survey. A filter question identified eight managers who were not eligible to participate because their program did not actively distribute needles at that time (our only study eligibility criterion). Of the remaining 117 potential participants, 104 initially responded to the survey; upon reviewing the data, we removed 24 surveys because of incomplete data, leaving 80 surveys for these analyses. Table 1 presents program characteristics. Throughout our results, we report the proportion of programs reporting each characteristic or practice.

Provision of safer crack cocaine smoking education

A majority of participants (0.76) reported that their program provides education to clients on reducing risks associated with sharing crack cocaine smoking equipment. Further, 0.75 indicated that their program provides education on identifying risks, such as cuts and injuries, from the use of improvised smoking equipment (e.g., soda cans as makeshift pipes), and 0.72 reported that they provide education on how to use safer smoking equipment.

Over three quarters of participants (0.78) reported that their program staff advise clients about when to replace smoking equipment. In terms of specific instances when it is time to replace smoking equipment, 0.75 of managers reported that their program advises clients to replace pipes and/or mouthpieces if these items have been used by anyone else; 0.74 advise clients to replace their pipe if it is scratched, chipped, or cracked; 0.71 advise clients to replace mouthpieces that are burnt; and 0.70 advise clients to replace the screen if it shrinks and becomes loose in the pipe.

We asked participants about the formats their programs use to provide education to clients about drug-related risk behaviors and practices. Given the general way in which we framed these questions, we cannot determine if and where the responses pertain to delivery of education on injection- or smoking-related behaviors, or both. With that caveat, we restricted these analyses to only managers who reported that their program provides education regarding how to use safer smoking equipment (n = 58) and found that all reported that their program offers educational information pamphlets or brochures; 0.97 offer one-on-one counseling; 0.79 offer demonstrations; 0.52 offer peer-delivered education; 0.38 offer skills-building sessions or group education; and 0.09 use instructional videos.

Distribution of safer crack cocaine smoking equipment

When asked if their program distributes “any” safer crack cocaine smoking equipment, 0.64 of managers responded affirmatively. Of these participants, nearly all (0.96) indicated that their program distributes pipes; over half (0.55) reported that their program has distributed safer smoking equipment for less than 5 years, while 0.43 have done so for more than 5 years and the remainder did not know how long their program has distributed this equipment. Of the programs that distribute pipes, 0.92 reportedly distribute the recommended heat-resistant Pyrex and/or borosilicate glass pipes, while 0.08 distribute pipes of an unknown type of glass. The proportions of managers who reported distribution of other pieces of safer smoking equipment were as follows: 0.94 for mouthpieces, 0.94 for screens, and 0.92 for push sticks. In addition to offering each piece of recommended equipment separately, 0.86 indicated that their program offers pre-packaged kits containing pipes plus other safer smoking equipment. In short, most of the programs that distribute safer smoking equipment reported giving out the recommended types of pipes as well as a complement of other safer smoking materials. Only 0.50 of our full sample reported that their program provides clients with containers for safer disposal of used smoking equipment.

Among participants who reported that their program does not distribute safer smoking equipment (0.35), the two most commonly endorsed reasons for not doing so were not enough funding (0.32) and lack of client demand (0.25). Only two participants selected “opposition from law enforcement” as a reason. Six managers wrote additional reasons in their surveys and three of these indicated that their programs are seeking to implement safer crack cocaine smoking equipment distribution and/or have received recent approval to do so.

When asked about distribution policies, 0.53 of managers who indicated that their program distributes pipes reported no maximum on the number of pipes that they will provide to a client at any one time; the remaining 0.47 indicated that their program sets a maximum. Reported limits ranged from one to 20 pipes per visit, though most commonly participants (0.57) indicated that their program imposes a maximum of one or two pipes per client at a time. When asked why their program imposes limits on pipe distribution, 0.61 of these managers reported that this quantity adequately meets client demand and 0.52 reported concerns about running out of supplies. Several participants added more information to their surveys that suggested that maximums are imposed due to concerns about clients selling their pipes on the street (e.g., “Some clients have been known to sell what they don’t use”). One participant added that a benefit of having a pipe limit is that it keeps clients who smoke crack cocaine coming back to their program for services (i.e., “to maintain continuity of contact with the clients so that we can provide support, education, and referrals”).

Influence of best practices on safer smoking education and distribution practices

Also as part of the online survey, we asked managers if they and their staff had used the recent set of national best practice recommendations [27] to change and align program practices with said evidence-based guidance. Just under half of participants (0.49) reported that their program used the recommendations to influence pipe distribution practices, 0.49 also did so to influence safer smoking education practices, and 0.39 did so to influence other smoking equipment (e.g., mouthpieces, screens) distribution practices.

Ontario: more programs distributing pipes over time

Finally, to examine potential changes in pipe distribution over time, we performed Ontario-specific sub-analyses and compared evaluation data collected in 2008 [25] with data from the 2015 survey. Analysis showed a significant increase in the proportion of programs distributing pipes in Ontario from 0.15 to 0.71.

Discussion

Our findings show that many NSPs in Canada offer safer crack cocaine smoking education and distribute equipment as recommended. In Ontario, there has been a significant increase in the number of programs distributing crack cocaine pipes since 2008. These findings are encouraging given that crack cocaine smoking occurs in cities across Canada and increases in use have been documented in some locations (e.g., [1–3]), and elevated rates of HCV and other health-related problems are reported among people who smoke crack cocaine [11–15], major reasons to engage this population in harm reduction services. However, there are important questions our study leaves unanswered or open for future investigations.

Although we found that some programs reported using the national best practice recommendations to influence safer crack cocaine education- and equipment-related practices, due to the cross-sectional nature of our survey and how we worded specific questions, we cannot state whether or not dissemination of said recommendations led to the observed levels of education provision and any increases in equipment distribution by NSPs. Overall, the evidence base supporting services for people who smoke crack cocaine is evolving and not as developed as that which supports harm reduction services for people who inject drugs—the latter backed by decades of research and recommended by international associations such as the World Health Organization [31]. More research is needed, for example, to solidify the linkage(s) between sharing pipes and HCV transmission [6]. That said, recent evidence demonstrates that access to safer smoking equipment can help to reduce health-related harm [32]. Research evidence is, nonetheless, one among numerous factors that impact health-related policy decisions.

Our study indicates an ongoing need to investigate and address barriers to best practice uptake, as 35% of managers in our sample reported that their program does not distribute any safer crack cocaine smoking equipment. More work is needed to address other domains found to promote uptake of evidence-based recommendations, including nurturing champions of organizational change, organizational cultures that support innovation and leaderships that promote the use of evidence-based practice, and ensuring adequate funding streams for distribution and disposal of safer smoking equipment [33, 34]. Only two managers among those who said that their programs do not distribute pipes selected police opposition as an underlying reason. This finding seems consistent with results from our larger evaluation study which show that the majority of NSP managers we sampled reported mostly positive relationships with their local law enforcement [35]. However, interpretation of this finding is difficult in light of other research that has reported policing practices to be a barrier to services designed for people who smoke crack cocaine (e.g., [19, 24]). Police support and opposition regarding harm reduction programs are dynamic, though, for example, in Canada there are signs that police perspectives on supervised injection facilities have changed in recent years, seemingly linked to the opioid overdose epidemic (cf. [36, 37]). How police may view services for people who smoke crack cocaine and how those views are changing or may change are worthy of in-depth investigation.

Lastly, although collection and safer disposal of used injection equipment is a core activity of NSPs, including providing clients with rigid, tamper-resistant, and clearly labeled sharps containers (see [27] for evidence-based best practice recommendations regarding disposal and handling of used drug-use equipment), we found that only half of all NSPs that we sampled provide clients with containers for safer disposal of used smoking equipment. We did not include more detailed or follow-up questions about this issue in the online survey, so we are unsure if this lack of safer disposal container provision represents a resource or cost issue and/or something else. We know from anecdotal reports from members of the cross-regional, multi-stakeholder best practice team that cost can be a barrier and some programs already struggle to cover the costs of injection equipment disposal. It is also possible that NSP staff do not regard pipes and other safer smoking equipment as sharps and/or biohazard material requiring the same level of safety procedures as used injection equipment. The removal from circulation and safer disposal of used injection equipment have long been considered key elements of NSP strategies to reduce needle reuse and accidental needle-stick injuries which, in turn, reduce opportunities for infectious disease transmission [38, 39]. More research is needed to determine if disposal is similarly as important for reducing certain risks associated with crack cocaine smoking.

In terms of study limitations, our findings may not be generalizable across all programs in Canada. One province with many NSPs and other harm reduction programs did not participate. It is also possible, though perhaps unlikely, that there are some programs that distribute safer smoking equipment and no injection equipment, and these would have been excluded from our survey. Although not an ideal sample, we otherwise captured data from programs from all other regions, including the Maritimes and the northern territories, and are thus able to provide a highly unique snapshot of Canadian practices. Our findings can provide some guidance for future, larger-sample investigations to describe and report on relationships involving harm reduction programs and safer crack cocaine smoking education and equipment.

Conclusions

Our findings point to important efforts on the part of Canadian NSPs to help reduce HCV and other health-related harm among people who smoke crack cocaine through provision of education and equipment that aim to address such harm. HCV is a preventable infection, and although at times challenging to implement harm reduction interventions, increased efforts are needed to reduce drug-related HCV risk in Canada and elsewhere in the world. Although beyond the scope of this article, we also stress that while client education and equipment distribution have a role to play in reducing such risk, ultimately improving the health and well-being of people who smoke crack cocaine requires much broader attention to social-structural factors—including social marginalization and drug law enforcement—that continue to disproportionately impact this population and drive much of their drug-related risk behaviors [40].

Abbreviations

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- NSPs:

-

Needle and syringe programs

References

Fischer B, Rudzinski K, Ivsins A, Gallupe O, Patra J, Krajden M. Social, health and drug use characteristics of primary crack users in three mid-sized communities in British Columbia. Canada Drug-Educ Prev Polic. 2010;17:333–53.

Paquette C, Roy E, Petit G, Boivin JF. Predictors of crack cocaine initiation among Montreal street youth: a first look at the phenomenon. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2010;110:85–91.

Werb D, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Modelling crack cocaine use trends over 10 years in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:271–7.

Faruque S, Edlin BR, McCoy CB, Word CO, Larsen SA, Schmid DS, et al. Crack cocaine smoking and oral sores in three inner-city neighborhoods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1996;13:87–92.

Porter J, Bonilla L, Drucker E. Methods of smoking crack as a potential risk factor for HIV infection: crack smokers’ perceptions and behavior. Contemp Drug Probl. 1997;24:319–47.

Fischer B, Powis J, Cruz MF, Rudzinski K, Rehm J. Hepatitis C virus transmission among oral crack users: viral detection on crack paraphernalia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:29–32.

Tortu S, McMahon J, Pouget E, Hamid R. Sharing of noninjection drug-use implements as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:211–24.

Cheng T, Wood E, Nguyen P, Montaner J, Kerr T, DeBeck K. Crack pipe sharing among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34:259–66.

Malchy LA, Bungay V, Johnson JL, Buxton J. Do crack smoking practices change with the introduction of safer crack kits? Can J Public Health. 2011;102:188–92.

Ti L, Buxton J, Wood E, Shannon K, Zhang R, Montaner J, et al. Factors associated with difficulty accessing crack cocaine pipes in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:890–6.

DeBeck K, Kerr T, Li K, Fischer B, Buxton J, Montaner J, et al. Smoking of crack cocaine as a risk factor for HIV infection among people who use injection drugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:585–9.

Hagan H, Perlman DC, Des Jarlais DC. Sexual risk and HIV infection among drug users in New York City: a pilot study. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:201–7.

Macias J, Palacios RB, Claro E, Vargas J, Vergara S, Mira JA, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among noninjecting drug users: association with sharing the inhalation implements of crack. Liver Int. 2008;28:781–6.

Story A, Bothamley G, Hayward A. Crack cocaine and infectious tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Diseases. 2008;14:1466–9.

Tortu S, Neaigus A, McMahon J, Hagen D. Hepatitis C among noninjecting drug users: a report. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36:523–34.

Ball AL. HIV, injecting drug use and harm reduction: a public health response. Addiction. 2007;102:684–90.

Cross JC, Johnson BD, Rees Davis W, Liberty HJ. Supporting the habit: income generation activities of frequent crack users compared with frequent users of other hard drugs. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2001;64:191–201.

Harwick L, Kershaw S. The needs of crack-cocaine users: lessons to be learnt from a study into the needs of crack-cocaine users. Drugs Educ Prev Polic. 2003;10:121–34.

Ivsins A, Roth E, Nakamura N, Krajden M, Fischer B. Uptake, benefits of and barriers to safer crack use kit (SCUK) distribution programmes in Victoria, Canada—a qualitative exploration. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:292–300.

Barnaby L, Clarke S, McCollum C, Okazawa V, Panter B, Steer L. Toronto crack users perspectives: inside, outside, upside down. Toronto: Safer Crack Use Coalition; 2005.

Johnson J, Malchy L, Mulvogue T, Moffat B, Boyd S, Buxton J, et al. Lessons learned from the SCORE project: a document to support outreach and education related to safer crack use. Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 2008.

Betteridge G. Toronto: cracking down on crack pipes. HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2006;11:25–6. 29.

Leonard L, DeRubeis E, Pelude L, Medd E, Birkett N, Seto J. “I inject less as I have easier access to pipes”: injecting, and sharing of crack-smoking materials, decline as safer crack-smoking resources are distributed. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:255–64.

McNeil R, Kerr T, Lampkin H, Small W. “We need somewhere to smoke crack”: an ethnographic study of an unsanctioned safer smoking room in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:645–52.

Strike C, Watson TM, Lavigne P, Hopkins S, Shore R, Young D, et al. Guidelines for better harm reduction: evaluating implementation of best practice recommendations for needle and syringe programs (NSPs). Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:34–40.

Watson TM, Strike C, Kolla G, Penn R, Jairam J, Hopkins S, et al. Design considerations for supervised consumption facilities (SCFs): preferences for facilities where people can inject and smoke drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24:156–63.

Strike C, Hopkins S, Watson TM, Gohil H, Leece P, Young S, et al. Best practice recommendations for Canadian harm reduction programs that provide service to people who use drugs and are at risk for HIV, HCV, and other harms: part 1. Toronto: Working Group on Best Practice for Harm Reduction Programs in Canada; 2013.

Watson TM, Strike C, Challacombe L, Demel G, Heywood D, Zurba N. Developing national best practice recommendations for harm reduction programmes: lessons learned from a community-based project. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;41:14–8.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2014.

Strike C, Watson TM, Gohil H, Miskovic M, Robinson S, Arkell C, et al. Best practice recommendations for Canadian harm reduction programs that provide service to people who use drugs and are at risk for HIV, HCV, and other harms: part 2. Toronto: Working Group on Best Practice for Harm Reduction Programs in Canada; 2015.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Prangnell A, Dong H, Daly P, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Hayashi K. Declining rates of health problems associated with crack smoking during the expansion of crack pipe distribution in Vancouver, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2012;17:163.

Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201.

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2.

Strike C, Watson TM. Relationships between needle and syringe programs and police: an exploratory analysis of the potential role of in-service training. Drug Alcohol Depen. in press.

Gray J. Toronto mayor, police chief onside for supervised drug injection sites. In: The Globe and Mail. 2016. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/toronto-police-chief-drops-opposition-to-safe-injection-sites/article30608788/. Accessed 13 Feb 2017

Watson TM, Bayoumi A, Kolla G, Penn R, Fischer B, Luce J, et al. Police perceptions of supervised consumption sites (SCSs): a qualitative study. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47:364–74.

Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Vlahov D, Junge B, Rathouz PJ, Galai N, et al. Discarded needles do not increase soon after the opening of a needle exchange program. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:730–7.

Kaplan EH, Heimer R. A circulation theory of needle exchange. AIDS. 1994;8:567–74.

Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:S135–45.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the following staff and team members who contributed their time and expertise to the larger best practices project, as this evaluation would not have been possible without their valuable work and insights: Ashraf Amlani, Camille Arkell, Jane Buxton, Hemant Gohil, Natalia Gutiérrez, Shaun Hopkins, Hugh Lampkin, Jenny Lebounga Vouma, Pamela Leece, Lynne Leonard, Lisa Lockie, Peggy Millson, Miroslav Miskovic, Carole Morissette, Diane Nielsen, Darren Petersen, Samantha Robinson, Despina Tzemis, and Sara Young.

Funding

This study was not externally funded.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

CS and TMW conceptualized the study, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Best Practice Recommendations Survey. (DOC 70 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Strike, C., Watson, T.M. Education and equipment for people who smoke crack cocaine in Canada: progress and limits. Harm Reduct J 14, 17 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0144-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0144-3