Abstract

Background

The Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (T.E.S.T) is a global antimicrobial surveillance study of both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. This report presents data on antimicrobial susceptibility among organisms collected in Mexico between 2005 and 2012 as part of T.E.S.T., and compares rates between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012.

Method

Each center in Mexico submitted at least 200 isolates per collection year; including 65 gram-positive isolates and 135 gram-negative isolates. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution methodology and antimicrobial susceptibility was established using the 2013 CLSI-approved breakpoints. For tigecycline US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) breakpoints were applied. Isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae with a MIC for ceftriaxone of >1 mg/L were screened for ESBL production using the phenotypic confirmatory disk test according to CLSI guidelines.

Results

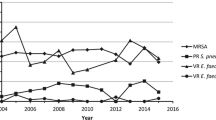

The rates of some key resistant phenotypes changed during this study: vancomycin resistance among Enterococcus faecium decreased from 28.6 % in 2005–2007 to 19.1 % in 2008–2012, while β-lactamase production among Haemophilus influenzae decreased from 37.6 to 18.9 %. Conversely, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus increased from 38.1 to 47.9 %, meropenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. increased from 17.7 to 33.0 % and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. increased from 25.6 to 49.7 %. The prevalence of other resistant pathogens was stable over the study period, including extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive Escherichia coli (39.0 %) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (25.0 %). The activity of tigecycline was maintained across the study years with MIC90s of ≤2 mg/L against Enterococcus spp., S. aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Serratia marcescens, H. influenzae, and Acinetobacter spp. All gram-positive organisms were susceptible to tigecycline and susceptibility among gram-negatives ranged from 95.0 % for K. pneumoniae to 99.7 % for E. coli.

Conclusion

Antimicrobial resistance continues to be high in Mexico. Tigecycline was active against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, including resistant phenotypes, collected during the study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The widespread occurrence of antimicrobial resistance among bacterial pathogens is a global concern, and infections caused by resistant bacteria are now frequent events in hospitalized or community patients. Countries in Latin America are recognised to have high levels of resistance and antimicrobial susceptibility has decreased among many pathogens in Mexico in recent years [1–8]. For example, in one tertiary care hospital in Mexico susceptibility to meropenem among Acinetobacter baumannii decreased from 91.7 % in 1999 to 11.8 % in 2011 [8].

The Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (T.E.S.T.) is a global in vitro antimicrobial surveillance study which started in 2004 and began collecting gram-positive and gram-negative isolates from Mexican centers in 2005. Susceptibility is tested against a range of antimicrobials, including tigecycline, by each medical center before shipping to a central laboratory; the central laboratory then carries out data validation and the collation of the T.E.S.T. database. In this report, we compare data for isolates collected between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012 as well as presenting data for 2005–2012 as a whole. This report serves as an update to some of the data presented in Rossi et al. [9], who presented data on antimicrobial susceptibility across Latin America between 2004 and 2007. Data for S. aureus collected across Latin America between 2004 and 2010 was previously published by Garza-González and Dowzicky [10] and data on gram-negative organisms collected across Latin America between 2004 and 2010 was previously published by Fernández-Canigia and Dowzicky [11]. These reports also contain data from Mexican centers which are included in this analysis.

Methods

In total, there were 16 centers in Mexico over the study period (1 center in 2005; 9 in 2006; 10 in 2007; 10 in 2008; 10 in 2009; 10 in 2010; 4 in 2011; and 15 in 2012). All centers did not participate in all years. The maximum number of years any one center participated for was 7 years. This was the case for two centers. One center participated for six years and four centers participated for 5 years. The remaining nine centers participated for between 2 and 4 years.

Isolates collection

Each participating centre submitted at least 200 isolates per collection year; including 65 gram-positive isolates [Enterococcus spp. (E. faecium and E. faecalis; n = 15), S. aureus (n = 25), Streptococcus agalactiae (n = 10), and S. pneumoniae (n = 15)] and 135 gram-negative isolates [Acinetobacter spp. (n = 15), Enterobacter spp. (n = 25), Escherichia coli (n = 25), Haemophilus influenzae (n = 15), Klebsiella spp. (K. oxytoca and K. pneumoniae; n = 25), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 20), and Serratia spp. (n = 10)].

All body sites were considered acceptable sources, although a maximum of 25 % of isolates could be urinary in origin. Inclusion of any isolate in the study was independent of patient medical history, previous antimicrobial use, age or gender. Only a single isolate was permitted from each patient. Ethics committee approval was not required as the study does not collect patient identifying information.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All participating medical centres were responsible for isolate identification and susceptibility testing. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for all pathogens and each antimicrobial agent in the T.E.S.T. panel were determined using Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution methodology [12], and either MicroScan® panels (Dade Microscan Inc., West Sacramento, CA, USA) or Sensititre® plates (TREK Diagnostic Systems, East Grinstead, UK). The core T.E.S.T. antimicrobial panel included: amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem or meropenem, levofloxacin, minocycline, piperacillin-tazobactam and tigecycline. Imipenem was replaced by meropenem in 2006 due to imipenem stability issues, while MicroScan® panels were replaced by Sensititre® plates. Gram-positive pathogens were tested against the core antimicrobials plus linezolid, penicillin and vancomycin; gram-negative isolates were tested against the core panel as well as amikacin, cefepime and ceftazidime. The S. pneumoniae test panel was expanded in 2006 to include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin and clindamycin.

All isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae were tested for extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production while all H. influenzae were tested for β-lactamase production. Isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae with a MIC for ceftriaxone of >1 mg/L were screened for ESBL production using the CLSI phenotypic confirmatory disk test according to CLSI guidelines [13] using cefotaxime (30 µg), cefotaxime/clavulanic acid (30/10 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), and ceftazidime/clavulanic acid (30/10 µg) disks (Oxoid, Inc., Ogdensburg, NY, USA). Mueller–Hinton agar used in testing was manufactured by Remel, Inc. (Lenexa, KS, USA). An increase of >5 mm in the inhibition zone of the combination disk when compared to that of the cephalosporin disk alone demonstrated ESBL production. H. influenzae isolates were tested for β-lactamase production using local methodologies.

Quality control (QC) strains were tested on each day of isolate testing. The QC strains used were E. coli ATCC 25922, H. influenzae ATCC 49247 and ATCC 49766, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, E. faecalis ATCC 29212, S. aureus ATCC 29213, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619. MIC data were used only if the daily QC test results were within ranges considered acceptable by CLSI [13].

All isolates were sent to International Health Management Associates, Inc. (IHMA, Schaumberg, IL, USA). IHMA were responsible for the organisation of isolate collection and transport and the management of a centralized database. IHMA were also responsible for carrying out isolate identification QC checks, which were conducted on approximately 10–15 % of isolates.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was established using CLSI-approved breakpoints. The 2013 version was used for all isolates in this study [13]. Tigecycline breakpoints, as published by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), were used in this analysis [14]. FDA tigecycline breakpoints for E. faecalis (vancomycin-susceptible) were used for all Enterococcus isolates.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of susceptibility between the 2005–2007 and 2008–2012 time periods were analysed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test with SAS (Version 8.2). Because of the large number of hypothesis tests, significance was determined at p < 0.01. The Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse changes in the percentage of resistant phenotypes between the two time periods, again using SAS (version 8.2). In this test significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and source data for the isolates in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 2 presents data on the antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive and gram-negative isolates collected in Mexico between 2005 and 2012. Among gram-positive isolates ≥99 % were susceptible to linezolid, tigecycline and vancomycin. The one exception to this was E. faecium as only 75.0 % of isolates were susceptible to vancomycin. For S. pneumoniae susceptibility data for isolates from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are presented separately from data for isolates from other culture sources. Among non-CSF isolates there was a statistically significant decrease in susceptibility between the two time periods for amoxicillin-clavulanate and penicillin (p < 0.01). For isolates of E faecalis rates of susceptibility were similar between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012; however, for E. faecium rates of susceptibility were higher in 2008–2012 than in 2005–2007 for all antimicrobials with less than 100 % susceptibility and in the cases of ampicillin and penicillin these differences were statistically significant (p < 0.01).

The activity of the antimicrobial panel against the gram-negative organisms varied with susceptibility to the carbapenems and tigecycline at ≥95 % against Enterobacter spp., E. coli, K. oxytoca and K. pneumoniae when examining the 2005–2012 data. Susceptibility among Acinetobacter spp. and P. aeruginosa was lower. The MIC90 for tigecycline against Acinetobacter spp. was 2 mg/L for the 2005–2012 and 0.5 and 2 mg/L for the 2005–2007 and 2008–2012 time periods, respectively. Decreases in susceptibility among the E. coli submitted were noted for a number of antimicrobials with the largest decreases in susceptibility seen for minocycline and piperacillin-tazobactam. Both these decreases were considered statistically significant (p < 0.0001). For K. pneumoniae statistically significant (p < 0.01) decreases in susceptibility to minocycline, piperacillin-tazobactam, amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftriaxone were seen between the two time periods. Susceptibility among Acinetobacter spp. was lower in 2008–2012 than in 2005–2007 for the majority of antimicrobial agents and decreases in susceptibility to amikacin, levofloxacin, meropenem, and minocycline were considered to be statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Antimicrobial susceptibility among MRSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, ESBL-positive E. coli and K. pneumoniae and MDR Acinetobacter spp. are presented in Table 3. Greater than 97 % of S. aureus were susceptible to linezolid, minocycline, tigecycline and vancomycin irrespective of methicillin status. The carbapenems and tigecycline have the highest rates of susceptibility against ESBL-positive E. coli and K. pneumoniae. The MIC90 for tigecycline against MDR Acinetobacter spp. was 2 mg/L for the 2005–2012 time period; between 2005 and 2007 the MIC90 was 1 mg/L and between 2008 and 2012 was 4 mg/L.

A total of 504 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter spp. and P. aeruginosa were identified in this study. Susceptibility data are presented in Table 4 K. oxytoca were not included in this table as only 2 isolates were identified.

Resistant phenotypes

Rates of resistant phenotypes for the three time periods are presented in Table 5. Rates of MRSA, meropenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. and MDR Acinetobacter spp. increased between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012 with the rates of meropenem-resistant and MDR Acinetobacter spp. increasing significantly (p < 0.05). In comparison, β-lactamase production among H. influenzae decreased significantly (p < 0.05) between the two time periods.

Discussion

Rates of antimicrobial resistance among both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms were high in this report from Mexico. Antimicrobial resistance is a recognized problem in Latin America with high levels of resistance among both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms [1–3]. There is a known relationship between antimicrobial use and resistance [15], and it can be surmised that one of the factors contributing to the high rates of resistance in Mexico is overuse of antimicrobials. Data on previous antimicrobial use is not collected by T.E.S.T.; however, such data would be of interest if the T.E.S.T. program were to develop in the future.

Overall, 45 % of S. aureus reported as MRSA, 22 % of E. faecium reported as vancomycin-resistant, 25 % of K. pneumoniae and 39 % of E. coli reported as ESBL-producers, 27 % of Acinetobacter spp. reported as resistant to meropenem and 42.8 % of Acinetobacter spp. were MDR. These results are similar to those presented by Jones et al. [3] for isolates collected in Mexico in 2011 where the MRSA rate was 48 % and 26 % of enterococci were vancomycin-resistant. ESBL rates among E. coli and K. pneumoniae were higher in the Jones et al. [3] report (71 and 56 %); however, as with this study, the rate of ESBLs was higher among E. coli than K. pneumoniae. SENTRY, which began in 1997, is also an antimicrobial surveillance program which collects isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility data from around the globe. Comparing susceptibility results for E. coli collected in Mexico through the SENTRY surveillance study (2008–2010) with results from this T.E.S.T. study show they were broadly comparable, with high levels of quinolone resistance occurring in both studies (34.4 % levofloxacin resistance in the current study, 35.4 % ciprofloxacin resistance in SENTRY) [16]. In addition, Klebsiella spp. susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone and cefepime was approximately 7–9 % higher in the SENTRY study than in T.E.S.T. for K. pneumoniae, although susceptibility was similar among other antimicrobial agents [16]. Carbapenem resistance among K. pneumoniae and E. coli was low in T.E.S.T. as has been previously reported for Mexico [17].

There was a variation in the susceptibility of S. pneumoniae to penicillin which was dependent on the breakpoints applied. For the 2005–2012 time period among non-CSF isolates susceptibility was 33.7 % using the oral or parenteral (meningitis) breakpoints but 93.1 % when using the parenteral (non-meningitis) breakpoints. Penicillin oral breakpoints are S ≤ 0.06 mg/L; I 0.12–1 mg/L; R ≥ 2 mg/L; whereas those for parenteral administered penicillin are: non-meningitis (S ≤ 2 mg/L; I 4 mg/L; R ≥ 8 mg/L) and meningitis (S ≤ 0.06 mg/L; R ≥ 0.12 mg/L). This highlights the importance of using the correct breakpoints when interpreting the susceptibility of an organism.

When comparing rates of resistance in Mexico with other countries the rate of MRSA (45 %) was similar to that reported for other Latin American countries such as Guatemala (49 %) and Panama (47 %) [3]. With limited treatment options, concern continues about the prevalence of MRSA globally and although rates have been reported to be decreasing in some regions, most notably North America and Europe [18, 19], the prevalence in other areas, particularly developing countries, is of increasing concern [20]. In their study of isolates collected between 2010 and 2014 Conceição et al. reported rates of 61.6 % in Angola, 25.5 % in São Tomé and Príncipe, 5.6 % in Cape Verde and 0.0 % in East Timor [21]. At 22 % the rate of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium was similar to that reported for enterococci in Brazil by Jones et al. (27 %) for 2011 [3]. It is also comparable to the rate of 18.5 % reported for Saudi Arabia in 2009–2010 [22]. The rates of ESBL producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae, although high, were relatively low when compared to some other countries. Sharma et al. reported that 67 % of Klebsiella spp. and 57 % of E. coli were ESBL producers in Jaipur, India in 2011–2012 [23]. Results for amikacin were similar in this study to the results reported for E. coli collected in Egypt but for K. pneumoniae susceptibility was higher in T.E.S.T. [24].

Antimicrobial susceptibility among P. aeruginosa was similar between the two time periods in this study and susceptibility rates were similar to those reported by Jones et al. for Latin America in 2011 [3]. In contrast, rates of susceptibility to amikacin and meropenem were lower than those reported by Gad et al. for P. aeruginosa isolates collected from three Egyptian hospitals [25]. In the case of Acinetobacter spp., resistance to meropenem increased from 17.7 % in 2005–2007 to 33.0 % in 2008–2012 in this T.E.S.T. program. Carbapenem resistance among Acinetobacter spp. has been reported both in Latin America and globally. For example, Oliveira et al. reported an increase in carbapenem resistance in Brazil from 7.4 % to 57.5 % between 1999 and 2008 and Aydin et al. reported an increase in meropenem resistance among Acinetobacter spp. collected from an ICU in Turkey from 26 % in 2008 to 95 % in 2011 [26, 27]. In addition a rate of 26 % was reported for a single center in India in 2013 although this was a decrease from the 33 % previously reported [28]. Other countries, such as Libya, are also reporting the emergence of carbapenem resistant A. baumannii [29]. These results demonstrate the variability in antimicrobial resistance between countries and with increasing globalization the importance of a global strategy to control the spread of resistant organisms.

Rossi et al. [9] examined the in vitro activity of tigecycline and comparator agents against gram-positive and gram-negative isolates from Latin America, including Mexico, between 2004 and 2007 as a part of the T.E.S.T. study. These data from Mexico are included in the current report but are updated with additional isolates. The most dramatic changes in susceptibility between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012 occurred among S. pneumoniae, E. faecium, K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca: ≥10 % changes were observed for seven antimicrobial agents against non-CSF S. pneumoniae [amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, meropenem, minocycline and penicillin (using oral or parenteral meningitis breakpoints], five antimicrobials against E. faecium (ampicillin, levofloxacin, minocycline, penicillin and vancomycin), five agents against K. pneumoniae (amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefepime, ceftriaxone, minocycline and piperacillin-tazobactam) and four antimicrobials against K. oxytoca (amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefepime, levofloxacin and piperacillin-tazobactam). All changes for E. faecium were increases in susceptibility, while for S. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca decreases in susceptibility were seen. These changes in antimicrobial susceptibility may be due to a number of factors. Firstly, between the two time periods there was an increase in the number of isolates coming from inpatients in this study. As isolates from inpatients and outpatients are known to have different susceptibility profiles this could impact the susceptibility profile of the isolates as a whole. Also, increases in susceptibility can be due to improved antimicrobial stewardship whereas decreases in susceptibility may occur due to failures in stewardship and center specific outbreaks. Over the counter dispensing of antimicrobials is common in Latin America and in 2010 Mexico sought to enforce existing laws to reduce their consumption. This policy has been shown to have decreased consumption [30], although a trend for decreasing consumption had already been detected [31]. The relationship between antimicrobial consumption and resistance is well known.

Linezolid, meropenem, tigecycline and vancomycin retained their good in vitro activity against most T.E.S.T. pathogens between 2005–2007 and 2008–2012.

The in vitro activity for tigecycline reported here is also comparable with the literature. Gales et al. [32] reported that all isolates of Enterococcus spp., S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae collected in Latin America between 2000 and 2002 were susceptible to tigecycline at MICs of ≤4 mg/L and MIC90s were ≤0.5 mg/L. Tigecycline retained this level of activity in the current study, with MIC90s for these organisms at ≤0.25 mg/L and 100 % tigecycline susceptibility reported among isolates of Enterococcus spp., S. aureus and S. pneumoniae and 98.2 % susceptibility reported among H. influenzae isolates. It is however, important to note that the breakpoints applied in this study are lower than the MIC cutoff used by Gales et al. [32]. The in vitro activity of tigecycline reported in this study for Mexico is also similar to that reported by Jones et al. [3] for gram-positive and gram-negative isolates collected across Latin America in 2011.

Breakpoints are not currently available for tigecycline against Acinetobacter spp. In this study the MIC90 for tigecycline was 0.5 mg/L between 2005–2007 and 2 mg/L for 2008–2012 and against MDR Acinetobacter spp. were one doubling dilution higher (1 and 4 mg/L, respectively). From the literature Garza-González et al. [4] reported an MIC90 for tigecycline of 0.5 mg/L among 550 A. baumannii isolates collected between 2006 and 2009 from a tertiary care teaching hospital in Mexico and Mendes et al. [33] reported a tigecycline MIC90 of 1 mg/L among 277 Acinetobacter spp. isolates from Mexico collected between 2005 and 2009.

As discussed above, rates of ESBL production are high in Mexico. In the current study, all ESBL-positive E. coli isolates and 95.3 % of ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae isolates were susceptible to tigecycline (data not shown). E. cloacae and S. marcescens are not examined for ESBLs as part of the T.E.S.T. study, but low levels of tigecycline non-susceptibility were observed in this study for both Enterobacter spp. (3.4 %) and S. marcescens (4.2 %). Silva-Sanchez et al. [34] have also reported good in vitro activity for tigecycline against ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae in Mexico (as well as MRSA), with >94 % of 1055 isolates reported as tigecycline susceptible. Tigecycline thus appears to be a potential treatment option in Mexico, where the prevalence of pathogens resistant to commonly-used antimicrobials is high.

Limitations of this study include the center repetition between years, with nine of the 16 centers participating for between two and four of the 8 years of study. The types of centers involved in surveillance studies can also influence results as large university hospitals and smaller community based hospitals can have differing levels of resistance. Both university and community based hospitals submitted isolates to the T.E.S.T. program in Mexico.

Surveillance studies such as SENTRY and T.E.S.T. are critical tools for monitoring the development and spread of resistance among important clinical pathogens, assisting healthcare professionals in making appropriate judgments for the best use of antimicrobials on regional or national levels and supporting antibiotic stewardship efforts [35, 36]. Tigecycline demonstrates good in vitro activity against most of the pathogens examined in this study, and should continue to be a useful option in the treatment of infectious diseases in Mexico.

References

Luna CM, Rodriguez-Noriega E, Bavestrello L, Guzmán-Blanco M. Gram-negative infections in adult intensive care units of Latin America and the Caribbean. Crit Care Res Pract. 2014;2014:480463.

Guzmán-Blanco M, Labarca JA, Villegas MV, Gotuzzo E, Latin America Working Group on bacterial resistance. Extended spectrum β-lactamase producers among nosocomial Enterobacteriaceae in Latin America. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18(4):421–33.

Jones RN, Guzman-Blanco M, Gales AC, Gallegos B, Castro AL, Martino MD, Vega S, Zurita J, Cepparulo M, Castanheira M. Susceptibility rates in Latin American nations: report from a regional resistance surveillance program (2011). Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(6):672–81.

Garza-González E, Llaca-Díaz JM, Bosques-Padilla FJ, González GM. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant bacteria at a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Mexico: special focus on Acinetobacter baumannii. Chemotherapy. 2010;56(4):275–9.

Silva-Sanchez J, Garza-Ramos JU, Reyna-Flores F, Sánchez-Perez A, Rojas-Moreno T, Andrade-Almaraz V, Pastrana J, Castro-Romero JI, Vinuesa P, Barrios H, Cervantes C. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae causing nosocomial infections in Mexico. A retrospective and multicenter study. Arch Med Res. 2011;42(2):156–62.

Llaca-Díaz JM, Mendoza-Olazarán S, Camacho-Ortiz A, Flores S, Garza-González E. One-year surveillance of ESKAPE pathogens in an intensive care unit of Monterrey. Mexico. Chemotherapy. 2012;58(6):475–81.

Morfin-Otero R, Tinoco-Favila JC, Sader HS, Salcido-Gutierrez L, Perez-Gomez HR, Gonzalez-Diaz E, Petersen L, Rodriquez-Noriega E. Resistance trends in gram-negative bacteria: surveillance results from two Mexican hospitals, 2005–2010. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:277.

Morfín-Otero R, Alcántar-Curiel MD, Rocha MJ, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Santos-Preciado JI, Gayosso-Vázquez C, Araiza-Navarro JR, Flores-Vaca M, Esparza-Ahumada S, González-Díaz E, Pérez-Gόmez HR, Rodríquez-Noriega E. Acinetobacter baumannii infections in a tertiary care hospital in Mexico over the past 13 years. Chemotherapy. 2013;59(1):57–65.

Rossi F, García P, Ronzon B, Curcio D, Dowzicky MJ. Rates of antimicrobial resistance in Latin America (2004–2007) and in vitro activity of the glycylcycline tigecycline and of other antibiotics. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12(5):405–15.

Garza-González E, Dowzicky MJ. Changes in Staphylococcus aureus susceptibility across Latin America between 2004 and 2010. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(1):13–9.

Fernández-Canigia L, Dowzicky MJ. Susceptibility of important Gram-negative pathogens to tigecycline and other antibiotics in Latin America between 2004 and 2010. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:29.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, Approved standard. 8th ed. Document M7-A8. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2009.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 23rd ed. Document M100-S23. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013.

Pfizer Inc. (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals): Tygacil® Product Insert. Pfizer. 2013. http://www.pfizerpro.com/hcp/tygacil/ (Version current at January 9, 2015).

Carlet J, Jarlier V, Harbarth S, Voss A, Goossens H, Pittet D, Participants of the 3rd World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. Ready for a world without antibiotics? The Pensières antibiotic resistance call to action. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1(1):11.

Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS. Antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008–2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73(4):354–60.

Rodríguez-Noriega E, León-Garnica G, Petersen-Morfín S, Pérez-Gómez HR, González-Díaz E, Morfín-Otero R. Evolution of bacterial resistance to antibiotics in México, 1973–2013. Biomedica. 2014;34(Suppl 1):181–90 (article in Spanish).

Cook PP, Rizzo S, Gooch M, Jordan M, Fang X, Hudson S. Sustained reduction in antimicrobial use and decrease in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile infections following implementation of an electronic medical record at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(1):205–9.

Hansen S, Schwab F, Asensio A, Carsauw H, Heczko P, Klavs I, Lyytikäinen O, Palomar M, Riesenfeld-Orn I, Savey A, Szilagyi E, Valinteliene R, Fabry J, Gastmeier P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Europe: which infection control measures are taken? Infection. 2010;38(3):159–64.

Mir BA, Srikanth Dr. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci in a tertiary case hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6(Suppl 3). http://www.ajpcr.com/Vol6Suppl3/237.pdf.

Conceição T, Coelho C, Santos Silva I, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. Staphylococcus aureus in former Portuguese colonies from Africa and the far East: missing data to help fill the world map. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(9):842.e1–842.e10.

Salem-Bekhit MM, Moussa IMI, Muharram MM, Alanazy FK, Hefni HM. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of multidrug-resistant enterococci isolated from clinical specimens. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2012;30(1):44–51.

Sharma M, Pathak S, Srivastava P. Prevalence and antibiogram of extended spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) producing gram negative bacilli and further molecular characterization of ESBL producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(10):2173–7.

Gad GF, Mohamed HA, Ashour HM. Aminoglycoside resistance rates, phenotypes, and mechanisms of gram-negative bacteria from infected patients in upper Egypt. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17224.

Gad GF, el-Domany RA, Ashour HM. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Egypt. J Urol 2008, 180(1):176–81.

Oliveira VD, Rubio FG, Almeida MT, Nogueira MC, Pignatari AC. Trends of 9416 multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2015;61(3):244–9.

Aydin M, Yavuz MT, Korkut O, Oldacay M. Antibiotic resistance profile of Acinetobacter strains isolated from patients in the intensive care unit: a surveillance study of four years. Mediterr J Infect Microb Antimicrob. 2013; 2(13). http://www.mjima.org/managete/fu_folder/2013-01/2013-2-13-001-006.pdf.

Alagesan M, Gopalakrishnan R, Panchatcharam SN, Dorairajan S, Mandayam Ananth T, Venkatasubramanian R. A decade of change in susceptibility patterns of gram-negative blood culture isolates: a single center study. Germs. 2015;5(3):65–77.

Mathlouthi N, Areig Z, Al Bayssari C, Bakour S, Ali El Salabi A, Ben Gwierif S, Zorgani AA, Ben Slama K, Chouchani C, Rolain JM. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates collected from some Libyan hospitals. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21(3):335–41.

Santa-Ana-Tellez Y, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Dreser A, Leufkens HG, Wirtz VJ. Impact of over-the-counter restrictions on antibiotic consumption in Brazil and Mexico. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75550.

Wirtz VJ, Dreser A, Gonzales R. Trends in antibiotic utilization in eight Latin American countries, 1997–2007. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2010;27(3):219–25.

Gales AC, Jones RN, Andrade SS, Pereira AS, Sader HS. In vitro activity of tigecycline, a new glycylcycline, tested against 1326 clinical bacterial strains isolated from Latin America. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;9(5):348–56.

Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Jones RN. Comprehensive assessment of tigecycline activity tested against a worldwide collection of Acinetobacter spp. (2005–2009). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68(3):307–11.

Silva-Sanchez J, Reyna-Flores F, Velazquez-Meza ME, Rojas-Moreno T, Benitez-Diaz A, Sanchez-Perez A, Study group. In vitro activity of tigecycline against extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and MRSA clinical isolates from Mexico: a multicentric study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(2):270–3.

Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, Fenelon L, Gould IM, Holmes A, Ramsey CR, Wiffen PJ, Wilcox M. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD003543.

Cantón R, Horcajada JP, Oliver A, Garbajosa PR, Vila J. Inappropriate use of antibiotics in hospitals: the complex relationship between antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2013;31(Suppl 4):3–11.

Authors’ contributions

RMO and ERN participated in data collection and interpretation as well as drafting and reviewing of the manuscript; MJD was involved in study design and participated in data interpretation and the drafting and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

No authors were paid for their contributions to this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all T.E.S.T. Mexico investigators and laboratories for their participation in the study and would also like to thank the staff at IHMA for their coordination of T.E.S.T. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Medical writing support was provided by Dr. Rod Taylor at Micron Research Ltd, Ely, UK and was funded by Pfizer Inc. Micron Research Ltd also provided data management services which were funded by Pfizer Inc.

Competing interests

RMO has received consulting fees from Wyeth. ERN is an Advisory Board member for Pfizer, Inc and has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Inc. MJD is an employee of Pfizer, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Morfin-Otero, R., Noriega, E.R. & Dowzicky, M.J. Antimicrobial susceptibility trends among gram-positive and -negative clinical isolates collected between 2005 and 2012 in Mexico: results from the Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 14, 53 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-015-0116-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-015-0116-y