Abstract

Background

A nosocomial outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) infections occurred among intensive care units (ICU) (surgery, medical, cardiovascular surgery, coronary unit) of Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Medical School (Rize, Turkey) between January 2011 and May 2012. The identification of isolates and clonal relation among them were investigated by molecular techniques.

Methods

A total of 109 AB isolates were obtained from 64 clinical materials from 54 ICU patients and 3 from the hands of healthcare workers (HCWs) of 42 environmental samples. The isolates were identified by 16S rDNA sequencing and OXA- specific PCR. The clonal relation between isolates was investigated by PFGE methods using ApaI restriction enzyme.

Results

All isolates were determined as AB by 16S rDNA sequencing and OXA-spesific PCR. While the blaOXA-51-like gene was amplified in all isolates, the blaOXA-23-like gene was amplified from 103 isolates. The PFGE pattern generated 9 pulsotypes and showed that the isolates from patients, HCWs, and the environment were genetically related. In 7 of these pulsotypes, there were 107 strains (98%) showing similar PFGE profiles that cannot be distinguished from each other, ranging from 2 to 53. The remaining 2 pulsotypes were comprised of strains closely associated with the main cluster. Two major groups were discovered with similarity coefficient of 85% and above. The first group consisted of 97 strains that are similar to each other at 92.7% rate, and the second group consisted of 12 strains that are 100% identical.

Conclusions

The common utilization of the blood gas device among ICU was the reason for the contamination. AB strains can remain stable for a long period of time, although due to the disinfection procedures applied in hospitals, there is a small chance that the same clone might reappear and cause another epidemic. For that reason, the resistance profiles of the strains must be continuously followed with amplification-based methods, and these methods should be used to support the PFGE method in the short term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB), a non-fermentative, gram-negative bacteria, is an opportunist agent commonly existing in nature [[1],[2]]. It can be alive for days on a lifeless surface and cause nosocomial infections in hospital environments [[3]-[5]]. Acinetobacter spp may especially cause ventilator-related pneumoniae and bacteriemia, urinary tract infections, secondary meningitis, and skin and wound infections [[6],[7]]. AB strains that are frequently isolated from nosocomial infections are resistant to many agents including carbapenems [[8]-[10]]. Recently, AB epidemics have been reported that are resistant to all antibiotics except polymixines, and this situation has led to a search for new drug options [[10]-[12]]. The problems in the production of any antibiotic drug and the resistant nature of the bacteria have caused a need for preventive interventions against the infections. Recently, several molecular-based studies have shown that the specific clones resistant to carbapenem have been persistent, and there is a possibility of clonal expansion throughout the world [[13]-[17]].

This study assessed the epidemic level of AB found in intensive care units (ICU) (surgery, medical, cardiovascular surgery, coronary care unit) from Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Hospital (RTEUH) between January 2011 and May 2012. It also evaluated its source, probable avenues of contamination, and its clonal relations to determine the effective control measurements for AB in RTEUH, which is a public hospital with 450 beds. Located in the east Black Sea region of Turkey, the hospital services around half a million people. There are 9 beds in the surgery intensive care unit (SICU); 8 beds in the medical intensive care unit (MICU); 6 beds in the cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit (CVSICU), in which all of them have ventilator equipment; and 16 beds in the coronary care unit (CICU), in which two of them have isolation rooms with ventilatory equipment. In a one and a half year period (January 2011 through May 2012), the number of patients hospitalized for RTEUH was 51,828, of which 1,132 were admitted to intensive care units.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

One hundred and nine AB strains were collected from RTEUH between January 2011 and May 2012. Samples were obtained from each ICU separately, from intravenous (IV) catheters, medication solutions, IV solutions, ICU environments, surfaces of the study areas, ventilators, laryngoscopy knives, incubators, taps, sinks, drug containers, IV drop supporters, monitors, tables, feeding pumps, patients’ charts or fields, mechanic ventilation (MV) equipment, intubation tubes, intubation knives, resuscitation equipment, resuscitation cars, and blood gas devices located in the corridor, comprising 8 square meters between surgery and the CVSICU. At the same time, samples were collected from ICU workers’ hands by a direct cultivation process. These hand samples of health workers were collected immediately after direct contact with a patient who required an emergency procedure.

Evaluating the epidemic

Based on data obtained by Hospital Infection Control Committee Team reports in January 2012, it was discovered that there was an AB epidemic in all ICUs during the last three months of year and simultaneously the preventive intervention had been started to get under control the epidemic. During the investigation, all suspect health procedures and infection control applications were analyzed. For the epidemiologic side of the investigation, cultures of the environment, equipment, hands of health workers, and other aforementioned items were evaluated. Because of the probability that the same strain caused the epidemic in the other four ICUs, the focus was directed to common contamination sources, common areas, equipment, transfer conditions, and personnel factors. The AB epidemic was not previously observed in the CVSICU previously and it was caused in the operating room. The blood gas instrument, frequently used during the cardiovascular surgery and commonly used temporarily by the SICU, CVSICU, CICU, and MICU, was examined to reach the source of contamination. At the beginning of May, a second investigation began because the cases continued to appear. From mid-January onward, on the first day a patient was admitted to any ICU and then weekly thereafter, cultures of the pharynx, axilla, and rectum of each patient were scanned.

Identification of A. baumanniiisolates

The samples obtained were cultured on bloody agar and EMB agar, and conventional methods plus a VITEK-2 Compact Automated System (bioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) were used for bacterial identification and antibiograms. The antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated strains was determined by the Kirby Bauer disk diffusion method (CLSI 2010) [[18]]. Ampicillin-sulbactam (10/10 μg), piperaciline-tazobactam 100/10 μg, cefepime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), tobramicin (10 μg), netilmicin (30 μg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25 μg/23 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), colistin (10 μg), and tigecycline (15 μg) antibiotic disks (Oxoid, UK) were used. P.aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was studied as the quality control strain. For colistin, the interpretive criteria of Galani et al. [[19]], and for tigecycline, the interpretive criteria of Jones et al. [[20]], were applied. The imipenem-resistant strains were detected by the disk diffusion method and confirmed by the imipenem E-test (Oxoid M.I.C Evaluator, UK).

16S rRNA gene sequencing of A. baumannii

Molecular identification of the isolates was performed by a 16S rRNA gene sequencing. AB isolates were grown in Luria Broth at 37°C overnight and collected by centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. A pellet was suspended in 300 μl of distilled water and boiled for 10 min. It was then centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was transferred into a new tube and used as a DNA template. The oligonucleotide primers of 27 F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3 as forward) and 1492R (5′-GGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ as reverse) (Macrogen) were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene for isolate. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) contained 10 μl of 5X Taq DNA polymerase reaction buffer (Promega), 200 mM of each dNTP, 10 pmol of the opposing primers, 1.5 U of GoTaqFlexi Polymerase (Promega, USA), 3 mM of MgClμ, and 5 μl genomic DNA in a final volume of 50 μl reaction volume. The PCR was performed under the following conditions: 2 min initial denaturation at 94°C; 35 cycles of denaturation (45 s at 94°C), annealing (60 s at 55°C), and extension (60 s at 72°C); and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Finally, the PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel and then visualized under UV light by staining with ethidium bromide. The PCR product was sent to Macrogen (The Netherlands) for sequencing. The same primer pairs were used for sequencing. The obtained sequence was analyzed by BLAST searches using the NCBI GenBank database [[21]].

Multiplex PCR for detection of blaOXAgenes

Multiplex PCR was used for detecting blaOXA-51-like, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-40-like, and blaOXA-58-like genes [[22]]; and blaOXA-48 [[23]] was investigated separately. The primers used in obtaining the PCR amplifications and the expected size of those PCR amplifications are shown in Table 1. DNA extracts were conducted using a boiling method. PCRs were performed in a final volume of 50 μL and included 5 μL of genomic DNA, 20 pM of each primer, 10 μL reaction buffer (Promega), 3 μL 25 mM MgCl2, 200 μM of each dNTPs, and 1.5 U of Taq Polymerase (Promega). PCR amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min followed by 30 cycles of 25 s at 94°C, 40 s at 52°C and 50 s at 72°C, with a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. All PCR results were analyzed on 1% agarose containing 0.5 mg/L ethidium bromide and subsequently visualized under UV light.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis

The clonal relation among AB strains were analyzed according to the suggested protocol, by Durmaz et al. [[24]], using the ApaI restriction enzyme for the PFGE method. After PFGE, a dendogram analysis of band profiles was carried out using the Bionumerics (Applied Maths, Inc., Belgium, 6.01 version) program. In the evaluation of the clonal relations, the criteria suggested by Tenover et al. was used [[25]].

Results

One hundred and nine AB isolates were collected from 64 clinical materials (3 of bronchoalveloar lavage, 2 of urine, 8 of blood, 2 of catheter, 1 of gaita, 1 of vagina, 4 of wound, 43 of tracheal aspirate cultures) from a total of 54 patients, 42 samples from a total of 233 environmental samples, and 3 from workers’ hands from a total of 18 personnel. Fifty AB isolates, obtained from 64 clinical samples from all four ICUs, were the cause of the hospital infection (35 of them were ventilator-related pneumoniae, 10 of them were bacteremia, 2 of them were urinary tract infections, and 3 of them were surgical area infections), and the rest (14) were due to colonization (Figure 1). All isolates were confirmed by biochemical characterization and 16S rDNA sequencing analysis. A hospital infection diagnosis was carried out using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria. Infection speed and invasive tool use rates were calculated in accordance with the requirements of the National Hospital Infections Surveillance Web (NHISW). Nineteen of the 54 patients infected with AB died.

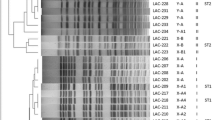

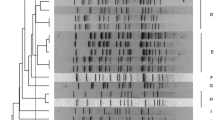

All isolates were resistant to carbapenems and multiple antibiotics but sensitive to colistin and tigecycline. The highest resistance rate was found for ciprofloxacin, followed by piperacillin-tazobactam, with a 97.2% rate, and cefepime (Table 2). Imipenem and meropenem resistance were found at 91.9% and 93.5%, respectively. An E-test was carried out on all imipenem resistant strains; all were found as ≥ 32 μg/mL. bla OXA-51-like was found as positive in all 109 strains, whereas blaOXA-23-like was positive in 103 strains, while blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-48-like, and blaOXA-58-like were not determined (Figure 2). Nine pulsotypes were detected by evaluating all 109 strains with PFGE, using an ApaI restriction enzyme. In 7 of these pulsotypes, there were 107 strains (98%) showing similar PFGE profiles that could not be distinguished from each other, ranging from 2 to 53. Two of the pulsotypes were comprised of a strain closely associated with the main cluster. Given the similarity coefficient as 85% and above, two major groups were discovered. The first group consisted of 97 strains that are similar to each other at a 92.7% rate, and the second group consisted of 12 strains that are 100% identical (Figure 3).

During the epidemic, control strategies were determined with the assistance of an infectious disease specialist, an infection control nurse, and responsible doctors of all four ICUs and their nurses. It was separated blood gas device utilization as the first strategy and increased the number of these devices to four: one for surgery and the CVSICU, one for the MICU, one for the CICU, and one in emergency services. The devices were blocked for use and they were made available to health care workers when absolutely necessary. The second strategy was placing affected patients in isolated rooms. With very strict contact measures, all health personnel working in ICUs were informed one by one of the need for the prevention of cross-contamination when using their hands. The importance of controlling hand hygiene and environmental pollution were highlighted. Disposable gloves and gowns were provided for all personnel caring for affected patients, and permission to enter the isolated rooms was granted to only a few necessary individuals. The third strategy was the blocking of patient transfers between the ICUs and exchange of personnel. The fourth strategy limited environmental pollutions in the ICUs, as all ICUs were cleaned thoroughly. All surfaces were completely cleaned with 600 ppm sodium dichloroisocyanurate. Isolated rooms also were cleaned last and separately. The fifth strategy aimed to prevent contamination or pollution of the environment during endotracheal aspirations by using a closed aspiration system. A closed aspiration system was introduced to all patients who required mechanical ventilation; for those who did require this mechanical aspiration, aseptic open aspiration techniques were followed. The control measures were followed until two negative culture results during weekly interval checks were reported. After patient discharge (or after exitus) from isolated rooms, the rooms were completely disinfected. After confirmation of negative environmental culture results, new patients were hospitalized. Special agents were used, such as carbapenem, which require a unique, restrictive, computerized prescription system that can only be accessed with approval of an infectious disease specialist. During the epidemic, this antibiotic policy was maintained.

From January 2011 onward, the number of new diagnosed cases increased. Although environmental cleaning and preventive measurements were conducted every month, pre- and post-cleaning strains were persistent. In January 2012, the number of new cases peaked, and in the following two months, the new epidemic control measures began to take hold and the number of cases started to decrease. No units were closed. After May, only one new case, requiring colonization, was detected in a health care worker.

Discussion

AB is an infectious species that causes severely progressive infections, and some of its isolates are resistant to most of antibiotics [[25]]. Although it is already resistant to multiple types of antibiotics, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, there has been an increase in recent years in the rates of carbapenem (potent antibiotic)-resistant AB strains. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases (carbapenemase) and molecular D class (OXA type enzymes) have been found responsible for the basic mechanism of resistance [[26]]. Hospital epidemics caused by carbapenem-resistant AB (CRAB) have caused concern throughout the world [[27]]. In recent years, AB epidemics due to carbapenem-resistant strains have increased in ICUs [[28],[29]].

According to Ministry of Health 2012 National Hospital Infections Surveillance Web reports, antimicrobial resistance rates (percentiles) were as follows: throughout Turkey, in 315 hospitals with 170 units, the number of carbapenem-resistant AB was 9,196, the number of resistant strains was 7,114. The number of CRAB was 3145, the number of resistant strain was 2627. In our study, all strains were found to be sensitive to colistine and tigecycline. The biggest resistance was seen in ciprofloxacin with a 98.2% rate, followed by piperacillin-tazobactam and cefepime with a 97.2% rate. Imipenem resistance was 91.9% and meropenem resistance was 93.5%. It could well be attributable by the frequent use of empirical antibiotics such as cephalosporins and quinolones in icus

It could well be stemmed by the use of empirical antibiotics such as cephalosporins and quinolones in ICUs. Compared to the carbapenem resistance rate with other reported rates in our country, 50% to 75% of the rates were associated with a lower sample size. Previous studies have shown that each hospital, and even each nation, has to develop infectious control strategies against multi-drug resistant AB using a multidisciplinary approach [[7],[30],[31]]. These strategies, including the use of covered aspiration systems and appropriate antibiotic use, will control comprehensive environmental decontaminations [[30]-[32]]. Thus, several studies showed that some epidemics can be controlled by such measures [[30]-[34]], although extremely persistent strains may be very difficult to control. This situation requires continuing follow-up [[35],[36]].

In the literature, total genom polymorphism with PFGE is the most reliable method for assessing the epidemiology of epidemics, and this is accepted as a “gold standard” for genotyping [[24],[30],[37],[38]]. According to the results of this study, PFGE has enough discriminatory power for clonal separation in follow-up of both short- and long-term periods, but strains could well obtain the blaOXA genes from different strains or microorganisms in time. Thus, it is imperative that the resistance profiles of strains must be continuously followed with amplification-based methods, and these methods should be used to support the PFGE method in the short term. According to the PFGE method, the one clone is responsible for Acinetobacter epidemics in hospitals.

Our results showed that the same strain has been responsible for contamination in all the ICUs, stemming from commonly used equipment that was contaminated by workers. An evaluation of contamination sources, using cultures from patients and environmental samples, has indicated that the epidemic might stem from commonly used blood gas analysis devices. Working personnel could well be responsible for the environmental contamination and the resulting cross-contamination. Seen retrospectively, the persistence over a period of months of the same strain in four different ICUs raised doubts about the contamination source. Infection control strategies, such as decreasing environmental pollution and using antibiotics appropriately, were employed while using equipment and transporting patients and in tactile contact with health care workers. Although there was AB persistency, a decrease in cases was achieved before reaching an epidemic level causing units to be shut down.

In conclusion, OXA type beta-lactamases have traveled swiftly among CRAB strains, consequently bringing carbapenem resistance to dangerous levels. These strains could be stable for a long time, although the disinfection procedures applied in hospitals could result in a slight chance that the same clone might cause another epidemic. In this context, to prevent persistent bacteria from causing hospital infections like AB, it is imperative that prevention and follow-up procedures be conducted on a continuous basis, and there is a need for more comprehensive molecular follow-up studies.

References

Garnacho-Montero J, Amaya-Villar R: Multiresis-tant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: epidemiology and management. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010, 23: 332-339. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833ae38b.

Gordon NC, Wareham DW: Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms of virulence and resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010, 35: 219-226. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.024.

Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Fernández-Hinojosa E, Aldabó-Pallás T, Cayuela A, Marquez-Vácaro JA, Garcia-Curiel A, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ: Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia: epidemical and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31: 649-655. 10.1007/s00134-005-2598-0.

Ayan M, Durmaz R, Aktas E, Durmaz B: Bacteriological, clinical and epidemiological characteristics of hospital-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii infection in a teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2003, 54: 39-45. 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00076-8.

Hosoglu S, Hascuhadar M, Yasar E, Uslu S, Aldudak B: Control of an Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in a neonatal ICU without suspension of service: a devastating outbreak in Diyarbakir, Turkey. Infection. 2012, 40: 11-18. 10.1007/s15010-011-0180-y.

Schreckenberger PC, Daneshvar MI, Hollis DG: Acinetobacter, Achromo-bacter, Chryseobacterium, Moraxella ve diğer nonfermentatif gram-negatif basiller. Klinik mikrobiyoloji. Edited by: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA. 2009, Atlas Kitapçılık, Ankara, 770-802. Edited by: A. Başustaoğlu, 9,

Towner KJ: Acinetobacter: an old friend, but a new enemy. J Hosp Infect. 2009, 73: 355-363. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.032.

Poirel L, Nordmann P: Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006, 12: 826-836. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01456.x.

Gordon NC, Wareham DW: A review of clinical and microbiological outcomes following treatment of infections involving multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii with tigecycline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009, 63: 775-780. 10.1093/jac/dkn555.

Kalin G, Alp E, Akin A, Coskun R, Doganay M: Comparison of colistin and colistin/sulbactam for the treatment of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia. Infection. 2013, ᅟ: ᅟ-doi:10.1007/s15010-013-0495-y

Peleg AY, Potoski BA, Rea R, Adams J, Sethi J, Capitano B, Husain S, Kwak EJ, Bhat SV, Paterson DL: Acinetobacter baumannii bloodstream infection while receiving tigecycline: a cautionary report. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007, 59: 128-131. 10.1093/jac/dkl441.

Zer Y, Özgür E, Namıduru M: Acinetobacter baumannii suşlarında tigesiklin etkinliğinin araştırılması. İnfeksiyon Derg. 2007, 21: 193-196.

Coelho JM, Turton JF, Kaufmann ME, Glover J, Woodford N, Warner M, Palepou MF, Pike R, Pitt TL, Patel BC, Livermore DM: Occurrence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clones at multiple hospitals in London and Southeast England. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 3623-3627. 10.1128/JCM.00699-06.

Idzenga D, Schouten MA, van Zanten AR: Outbreak of Acinetobacter genomic species 3 in a Dutch intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2006, 63: 485-487. 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.03.014.

Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, van der Reijden TJ: Long-term predominance of two pan-European clones among multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in the Czech Republic. J Med Microbiol. 2004, 53: 147-153. 10.1099/jmm.0.05445-0.

Turton JF, Kaufmann ME, Warner M, Coelho J, Dijkshoorn L, van der Reijden T, Pitt TL: A prevalent multiresistant clone of Acinetobacter baumannii in Southeast England. J Hosp Infect. 2004, 58: 170-179. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.05.011.

Van Dessel H, Dijkshoorn L, van der Reijden T, Bakker N, Paauw A, van den Broek P, Verhoef J, Brisse S: Identification of a new geographically widespread multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii clone from European hospitals. Res Microbiol. 2004, 155: 105-112. 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.10.003.

Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twentieth informational supplement, M100-S20. 2010, CLSI, Wayne, PA

Galani I, Kontopidou F, Souli M, Rekatsina PD, Koratzanis E, Deliolanis J, Giamarellou H: Colistin susceptibility testing by E test and disk diffusion methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008, 31 (5): 434-439. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.011.

Jones R, Feraro M, Relle L, Schreckenbeger P, Swenson J, Sader H: Multicenter studies of tigecycline disk diffusion susceptibity results for Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 6: 227-230. 10.1128/JCM.01588-06.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2.

Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM, Turton JF, Ward ME, Brown S, Amyes SG, Livermore DM: Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agent. 2006, 27: 351-353. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004.

Poirel L, Heritier C, Tol’un V, Nordmann P: Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004, 48: 15-22. 10.1128/AAC.48.1.15-22.2004.

Durmaz R, Otlu B, Koksal F: The optimization of a rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for the typing of Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009, 62: 372-377.

Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B: Interpre-ting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33: 2233-2239.

Giamarellou H, Antoniadou A, Kanellakopoulou K: Acinetobacter baumannii: a universal threat to public health?. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008, 32: 106-119. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.02.013.

Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P: Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54: 24-38. 10.1128/AAC.01512-08.

Durante-Mangoni E, Zarrilli R: Global spread of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: molecular epidemiology and management of antimicrobial resistance. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6: 407-422. 10.2217/fmb.11.23.

Baran G, Erbay A, Bodur H, Onguru P, Akinci E, Balaban N, Cevik MA: Risk factors for nosocomial imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2008, 12: 16-21. 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.03.005.

Hande Aydemir GC, Nihal P, Nefise O, Aysegul Seremet K, Elif A, Vildan S, Deniz A: Mortality attributable to carbapenem-resistant nosocomial Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in a Turkish University Hospital. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012, 65: 66-71.

Lee K, Yong D, Jeong SH, Chong Y: Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp.: increasingly problematic nosocomial pathogens. Yonsei Med J. 2011, 52: 879-891. 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.6.879.

Choi WS, Kim SH, Jeon EG, Son MH, Yoon YK, Kim JY, Kim MJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Park DW: Nosocomial outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care units and successful outbreak control program. J Korean Med Sci. 2010, 25: 999-1004. 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.7.999.

Doidge M, Allworth AM, Woods M, Marshall P, Terry M, O’Brien K, Goh HM, George N, Nimmo GR, Schembri MA, Lipman J, Paterson DL: Control of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Australia after introduction of environmental cleaning with a commercial oxidizing disinfectant. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010, 31: 418-420. 10.1086/651312.

Consales G, Gramigni E, Zamidei L, Bettocchi D, De Gaudio AR: A multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in intensive care unit: Antimicrobial and organizational strategies. J Crit Care. 2011, 26: 453-459. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.12.016.

Lin WR, Lu PL, Siu LK, Chen TC, Lin CY, Hung CT, Chen YH: Rapid control of a hospital-wide outbreak caused by extensively drug-resistant OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011, 27: 207-214. 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.11.004.

Baang JH, Axelrod P, Decker BK, Hujer AM, Dash G, Truant AR, Bonomo RA, Fekete T: Longitudinal epidemiology of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter species in a tertiary care hospital. Am J Infect Control. 2012, 40: 134-137. 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.326.

Herruzo R, de la Cruz J, Fernández-Aceñero MJ, Garcia-Caballero J: Two consecutive outbreaks of Acinetobacter baumannii 1-a in a burn intensive care unit for adults. Burns. 2004, 30: 419-423. 10.1016/j.burns.2004.01.008.

Seifert H, Dolzani L, Bressan R, van der Reijden T, van Strijen B, Stefanik D, Heersma H, Dijkshoorn L: Standardization and interlaboratory reproducibility assessment of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-generated fingerprints of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43: 4328-4335. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4328-4335.2005.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Recep Tayyip Erdogan University Research Fund Grants BAP-2013.102.03.13, BAP-2013.102.03.12 and BAP-2013.102.03.4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AE and ACC designed the study, prepared the literature, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; AG, EC, AS, AK, AK, NA, CS, and RD collected the data about Acinetobacter baumannii isolates and generated the assays. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ertürk, A., Çiçek, A.Ç., Gümüş, A. et al. Molecular characterisation and control of Acinetobacter baumanniiisolates resistant to multi-drugs emerging in inter-intensive care units. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 13, 36 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-014-0036-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-014-0036-2