Abstract

This review examines the current literature on the effects of future emissions and climate change on particulate matter (PM) and O3 air quality and on the consequent health impacts, with a focus on Europe. There is considerable literature on the effects of climate change on O3 but fewer studies on the effects of climate change on PM concentrations. Under the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 5th assessment report (AR5) Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs), background O3 entering Europe is expected to decrease under most scenarios due to higher water vapour concentrations in a warmer climate. However, under the extreme pathway RCP8.5 higher (more than double) methane (CH4) abundances lead to increases in background O3 that offset the O3 decrease due to climate change especially for the 2100 period. Regionally, in polluted areas with high levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx), elevated surface temperatures and humidities yield increases in surface O3 – termed the O3 climate penalty – especially in southern Europe. The O3 response is larger for metrics that represent the higher end of the O3 distribution, such as daily maximum O3. Future changes in PM concentrations due to climate change are much less certain, although several recent studies also suggest a PM climate penalty due to high temperatures and humidity and reduced precipitation in northern mid-latitude land regions in 2100.

A larger number of studies have examined both future climate and emissions changes under the RCP scenarios. Under these pathways the impact of emission changes on air quality out to the 2050s will be larger than that due to climate change, because of large reductions in emissions of O3 and PM pollutant precursor emissions and the more limited climate change response itself. Climate change will also affect climate extreme events such as heatwaves. Air pollution episodes are associated with stagnation events and sometimes heat waves. Air quality during the 2003 heatwave over Europe has been examined in numerous studies and mechanisms for enhancing O3 have been identified.

There are few studies on health effects associated with climate change impacts alone on air quality, but these report higher O3-related health burdens in polluted populated regions and greater PM2.5 health burdens in these emission regions. Studies that examine the combined impacts of climate change and anthropogenic emissions change under the RCP scenarios report reductions in global and European premature O3-respiratory related and PM mortalities arising from the large decreases in precursor emissions. Under RCP 8.5 the large increase in CH4 leads to global and European excess O3-respiratory related mortalities in 2100. For future health effects, besides uncertainty in future O3 and particularly PM concentrations, there is also uncertainty in risk estimates such as effect modification by temperature on pollutant-response relationships and potential future adaptation that would alter exposure risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported strengthened evidence for adverse health effects related to exposure to particulate matter (PM), ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) [1]. Their evidence comes from various types of epidemiological studies [2]. For PM, both short-term and long-term exposure to PM2.5 (particle diameter < 2.5 μm) is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. Evidence now also links long-term exposure with other health outcomes including adverse birth outcomes and childhood respiratory disease [1]. There is also strengthening evidence for short-term effects on mortality and morbidity from the larger particle size fractions PM10 (diameter < 10 μm).

For O3, short-term exposure is associated with all-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality, and respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions. There is now strengthened evidence for effects of long-term exposure to O3 on respiratory and cardiorespiratory mortality in warm season months [1], although taken as a whole this evidence is limited at present, as it is primarily derived from studies in North America [3]. For both PM and O3 there are indications that adverse effects exist down to low concentrations, such that it is hard to discern any threshold concentration. Whilst evidence has also strengthened for independent impacts of both short-term and long-term exposure to NO2 on mortality, hospital admissions and respiratory symptoms, because of strong correlations between NO2 and other air pollutants it remains difficult to discern a direct effect [1]. This, coupled with the current evidence that for both PM and O3 adverse effects exist down to low concentrations, means that this review focuses predominantly on these two pollutants: O3 and PM.

Emissions of the main air pollutant precursors: primary PM, black carbon (BC); nitrogen oxides (NOx); sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4) and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) in Europe have declined in the last decade or so, resulting in improvements in air quality across the region [4]. However, due to the complexities of the processes linking emissions and air quality, notably interactions with meteorology, reductions in local or regional emissions do not always produce a reduction in atmospheric concentrations. Hence air pollution remains a high profile issue, now and for the future.

This review examines the current evidence for the effects of climate change on ambient air quality and on the consequent health impacts over Europe. The topics covered in this review are as follows. First, current health burdens and risk estimates are outlined as well as health impacts from the well-documented 2003 heatwave over Europe. The sensitivity of O3 and PM to changes in climate and in climate extremes and the key driving processes are then reviewed. Air quality and health impacts associated with recent IPCC scenarios for a) future climate and with b) combined future climate and emissions are then described and key non-climate/emissions determinants of future air quality highlighted. Finally, this review presents conclusions and knowledge gaps.

Review

Current health burdens and risk estimates

The estimated health burdens attributable to ambient air pollution are substantial. The Global Burden of Disease project estimated that exposure to PM2.5 in 2015 contributed 4.2 million deaths globally, whilst exposure to O3 contributed 0.25 million deaths globally [5]. Across the European Union (EU), the European Environment Agency (EEA) estimated that about 467,000 people died prematurely in 2013 due to long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 [4]. For O3, the EEA estimated that short-term exposures in 2013 contributed to more than 17,000 premature mortalities [4]. This assumes a threshold concentration for effect of 35 ppbv (70 μg m−3). Whilst the proportions of the EU urban population exposed to ambient PM concentrations exceeding EU limit or target values have declined in the last decade, they have varied for exposure to O3 partly due to year-to-year variability in meteorology [4, 6].

Dose-response coefficients used to quantify the risk of mortality related to short and long-term exposure to PM2.5 and O3 are given in Table 1. For short-term exposure, these coefficients are mainly based on the Health Risks of Air Pollution In Europe (HRAPIE) WHO project [7]; for O3 results from the Air Pollution and Health: A European and North American Approach APHENA study [8] and the UK Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution (COMEAP) meta-analysis [3] are also provided. For long-term exposure, findings from long-term American Cancer Society (ACS) cohort studies are given [9, 10]. For long-term exposure to PM2.5, the WHO [7] suggest an increased premature mortality risk of 6.2% per 10 μg m−3 exposure measured using annual-mean PM2.5 concentrations (Table 1). For short-term exposure to O3, an increased premature mortality risk of 0.29% per 10 μg m−3 exposure measured using daily maximum 8-h running mean O3 is suggested by the WHO [7] (Table 1); they also recommend a threshold of 70 μg m−3 (35 ppbv) due to greater data availability for the warm season.

Current air pollution and health impacts - the 2003 heatwave analogue

Many interacting processes control the concentrations of O3 and PM at a given location: emissions, transport, transformation and deposition, all of which can be affected directly or indirectly by meteorology and climate. O3 has an average tropospheric lifetime of about a month [11]. The different components of PM have varying lifetimes but typical values are around ~1–2 weeks [12]. Horizontal transport times across the mid-latitudes are ~2 weeks [13], hence both O3 and PM can be transported across continents.

Elevated air pollution associated with extreme events such as summer heat waves has received much attention in the literature. Patz et al. [14] found heatwaves can often be associated with O3 exceedance days. In particular, the European heat wave of 2003 and the accompanying high O3 levels have been studied in detail [15,16,17,18]. Relevant processes identified include: persistent high-pressure systems and extended residence time in the atmospheric boundary layer, extensive forest fires, enhanced levels of natural biogenic isoprene (an O3 and PM precursor) and suppressed dry deposition of O3. Wildfires have also been associated with high PM2.5 levels [19]. High levels of O3 and PM10 are estimated to have contributed to one-third of the excess deaths occurring during the 2003 heatwave in the UK [20, 21]. In the Netherlands, Fischer et al. [22] estimated an excess of 1000–1400 deaths, with 400–600 of these deaths related to O3 and PM10. For nine cities in France (where the impacts of the 2003 heatwave were largest), Filleul et al. [23] estimated that the excess risk of death was significant (1.01%; 95% CI, 0.58–1.44) for an O3 increase of 10 μg m−3, and highlighted the joint risk due to temperature and O3. Studies suggest that summer 2003 could be a normal summer in the coming decades under climate change [24, 25]. Indeed, Stott et al. [26] estimated with >90% confidence that human influence has at least doubled the risk of a heatwave equivalent to that experienced across Europe in 2003. A detailed description of the influences of meteorological and climate variables in relation to climate change effects on O3 and PM concentrations is given below.

Future air quality and health impacts

Future air quality depends on several factors: anthropogenic emissions, natural emissions (that are climate sensitive), as well as climate change that results from changes in emissions of long-lived greenhouse gases. Future emission scenarios generally provide emission trajectories for both greenhouse gases used for climate projections as well as emissions for primary PM and precursor emissions of surface O3 and secondary PM. Hence, emissions and climate change are linked in this context of future air quality. In the following sections, first the effect of climate change including climate extremes on air quality is reviewed, and recent estimates of changes in air quality using the latest IPCC scenarios presented. Subsequently, studies that examine the impacts of the combination of climate and emissions changes on air quality and on human health burdens are featured. Absolute changes in future O3 or PM levels are discussed from multi-model estimates or from the most recent literature.

The impacts of climate change and change in climate extremes on O3 and PM air pollution

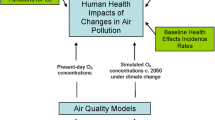

The impacts of important meteorological and climate variables on surface O3 and PM, are summarised in Fig. 1, which is based on comprehensive reviews [27,28,29] as well as studies outlined below. The key processes that influence air quality occur through changes in temperature, water vapour, precipitation and clouds, and meteorological transport and mixing. Climate variables not only influence air pollutant concentrations but they can also act as confounding and modifying factors of air pollution concentration-health response relationships. For example, Pattenden et al. [30] showed that adverse health effects of exposure to O3 were greater on the hottest days.

O3 is strongly correlated with temperature [31] due to associations of increased temperature with enhanced O3 photochemical reaction rates, as well as with stagnation events (discussed below), and with elevated natural emissions from biogenic and wild fire sources. In particular, several studies highlight that higher temperatures enhance rates of peroxyacetylnitrate (PAN) decomposition [32,33,34] leading to local NO2 and O3 increases in polluted emission regions. A number of these factors were also established as the cause of high levels of O3 during the 2003 heatwave (see above). Natural emissions of isoprene strongly increase with increasing temperature (but also decrease with increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide CO2). Several authors have highlighted the crucial role of the temperature sensitivity of isoprene emission, finding this to be the dominant mechanism for increasing O3 levels in polluted regions [33, 34]. However, CO2 inhibition of isoprene emissions in a future higher CO2 climate may offset temperature-driven emission increases [35,36,37,38,39,40]. In addition, Ito et al. [41] and Fiore et al. [29] suggest the O3 response to temperature depends on the amount of recycling of NOx from isoprene nitrates. Sustained elevated temperatures can lead to reduced soil moisture, which decreases dry deposition of O3 through plant stomata, and to increased wildfires which contribute to O3 precursor emissions. Another important global O3 precursor, methane (CH4), has a large natural emissions source from wetlands; these emissions are likely to increase under climate change along with CH4 emissions from other sources as a result of climate feedbacks (e.g. permafrost thaw) [42]. Forkel and Knoche [43] also suggest that elevated temperatures increase soil NOx emissions, which they found increased summer daily maximum surface O3 concentrations slightly in agricultural areas in Europe.

The overall effect of temperature-driven processes on PM is even more complex to disentangle than for O3 due to opposing influences on various PM components [29]. Elevated temperatures enhance sulphur dioxide (SO2) oxidation to sulphate aerosol [44, 45], and increase partitioning to the gas phase which reduces nitrate and some organic aerosol species [28, 29, 46, 47]. In particular, several studies over the USA suggest large decreases of nitrate PM with increasing temperature, and this is the dominant effect on PM concentrations in regions where nitrate is a relatively large component [28, 48], as is often the case in urban European regions. Large changes in PM are possible due to elevated emissions from biogenic and wild fire sources, yielding carbonaceous particles, mineral dust and secondary organic aerosol [29].

Specific humidity also plays an important role in chemistry as higher atmospheric water vapour (associated with elevated temperature) will increase O3 destruction in low-NOx environments e.g. [49], causing a reduction in ‘background’ concentrations of surface O3. However, higher water vapour also leads to higher HOx (OH + HO2) that enhances O3 in high NOx environments [28, 50]. For PM, increased water vapour alters aerosol properties and hygroscopic growth and through higher OH levels enhances SO2 oxidation leading to higher particle sulphate concentrations e.g. [45, 50]. Particle nitrate levels also increase with higher humidities [48]. Rainfall frequency and amount affects wet deposition processes that remove pollutants from the atmosphere. PM concentrations decrease in areas simulated to have increased precipitation frequency and vice versa [51,52,53]. Under climate change it is generally thought that wetter regions of the world will get wetter and drier regions drier [54, 55]. Cloud amount also affects the amount of incoming solar radiation and hence photolysis rates that influence surface O3. Several authors report increased summer surface O3 concentrations over Europe and the NE USA due to reduced cloud amounts that lead to enhanced photolysis rates [56,57,58], particularly that of NO2 which favours O3 formation [43].

Meteorological transport and mixing, in particular wind speed and direction and boundary-layer height, determines the dispersion, deposition or stagnation of pollutants and their precursors. However, change in many of these variables e.g. wind speed cannot be reliably predicted by global or regional climate models due to their dependence on small-scale features such as topography. Under climate change, convection is expected to be deeper, although less frequent [59, 60]. Lightning NOx emissions typically increase e.g. [11] although this finding may be sensitive to the model lighting scheme used [61]. Likewise, climate change is predicted to increase stratosphere-troposphere exchange as a result of an enhanced Brewer Dobson circulation [62] which increases the stratospheric contribution to surface O3 [63, 64]. Studies provide inconsistent results on the impact of climate change on mixing depth, with increases and decreases in different regions [52, 65,66,67].

Changes in climate and in climate extremes also have the potential to alter transport pathways e.g., [65, 68], which are influenced by the dominance and passage of both low and high pressure systems. For example, Glotfelty et al. [69] suggest that climate change, through an enhanced low pressure centre over eastern Russia increases intercontinental transport of air pollution from the region increasing global average O3 and PM2.5. However, Doherty et al. [34], using a passive tracer approach, found that shifts in transport patterns due to climate change are unlikely to have a major role in influencing the annual-mean O3 response, but may be important when considering changes in O3 metrics influenced by extreme values such as daily 8-h maximum surface O3. In particular, the frequency and magnitude of O3 and PM pollution episodes will likely be affected by climate change through changes in the frequency of low pressure system passage [68, 70] or the frequency of blocking episodes. Multi-model studies show a consistent decrease in winter and summer blocking over Europe in the twenty-first century [71]. However, in summer the accompanying poleward shift of the storm track into the region of frequent high-latitude blocking, may lead to a greater number of storms obstructed by blocking high pressure systems in the future [71]. Changes in large-scale blocking may affect local stagnation and heatwave episodes. However the relationship between blocking and stagnation remain unclear [72]. Indeed, Horton et al. [73] report an increase in annual-mean and springtime stagnation occurrences over Mediterranean Europe by the late twenty-first century. The authors noted that biases in modelled surface wind speeds used to create their air stagnation index were large. Overall, Kirtman et al. [74] concluded that evidence and agreement on the impact of climate change on transport pathways are still lacking.

Future climate scenarios and air quality impacts

Estimates of the global and regional average surface O3 response to climate change alone between 2000 and 2030 based on the review findings of Fiore et al. [29] for several greenhouse gas emission scenarios including the Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES) [75] and the latest IPCC Representative Concentration pathways (RCP) scenarios are depicted in Fig. 2 [74]. The ranges reflect multi-model differences in spatial averages (solid green lines) and spatial variability within a single model (dashed green lines). The global–mean temperature change projected with Global Climate Models (GCMs) driven by the SRES climate scenarios is 1.4–6.3 °C in the 2090s. GCM projections of global average warming using the RCP climate scenarios is between 0.3–1.7 °C for RCP 2.6 (the least extreme pathway representing 2.6 W m−2 net radiative forcing at 2100) and 2.6–4.8 °C for RCP 8.5 (the most extreme scenario) in 2100 compared to 1986–2005 [76].

Reproduction (with permission) of Figure 11.22 from chapter 11, IPCC WG1 Fifth Assessment Report (Kirtman et al. [74]) showing changes in surface O3 (ppb) between year 2000 and 2030 driven by climate alone (CLIMATE; green) or emissions alone following CLE (black), MRF (gray), SRES (blue) and RCP (red) emission scenarios. Bars represents multi-model standard deviation with the exception of the green dotted bar over Europe, which represents the range of climate-only changes in summer daily maximum O3 from a single-model study [43]. For further details, see Kirtman et al. [74]

Typically, larger O3 changes occur due to changes in emissions of short-lived O3 precursors alone as compared to climate change alone in the 2030s (Fig. 2). The decrease in global mean O3 is driven by higher water vapour and temperatures. The higher temperatures can lead to local O3 increases during the peak pollution season (2–6 ppbv) for Central Europe (green dashed line based on [43]). Overall, a warmer, moister climate increases O3 in polluted regions [74], the so-called “climate penalty effect” [68, 77,78,79].

Over the longer time frame out to 2100, studies of climate change impacts on air quality suggest the same effects on background O3 and on O3 in polluted regions as described above, but the impact is typically larger with the larger climate signal. In a multi-model study, Doherty et al. [34] suggest annual-mean O3 increases of up to 6 ppbv in polluted regions reaching 14 ppbv in the season of maximum O3 under the SRES A2 greenhouse gas or climate scenario. In a regional European multi-modelling study to 2050 using the SRES A1B climate scenario, Langner et al. [80] report that, in southern Europe, climate change leads to increased summer mean O3 (0–3 ppbv) and increased summer daily maximum O3 (3–6 ppb). In northern Europe, they found reductions (0–3 ppbv) for both mean and daily maximum O3 in summer. Collette et al. [79] also found similar geographical patterns of projected changes in O3 with an increase over southern continental Europe and a decrease over northern Europe and the British Isles. Several studies report climate change to have a greater impact on episodic O3 (e.g., the 95th percentile of hourly O3) than on longer-term (e.g., summer-mean) averages [50, 81]).

Most recently, several studies have suggested a PM climate penalty in the future [45, 53]. A PM climate penalty simulated in 2050 and 2100 in the eastern USA was attributed to enhanced sulphate concentrations associated with higher temperatures and humidities [45]. A recent multi-model study suggested that climate change, simulated under the RCP 8.5 climate scenario, increases the aerosol burden and surface PM concentrations, through a reduction in large-scale precipitation over northern mid-latitude land regions [53]. Over Europe, one regional modelling study reported the geographical patterns of the impact of climate on surface summer PM levels to be less robust than for O3 [82].

There is high agreement from modelling studies projecting increases in the frequency and duration of extreme O3 pollution events but there is large variability in predicted spatial pattern and incidence of these events [28, 29]. However, the collective evidence suggests that increasing temperatures during air stagnation episodes in polluted environments will increase peak pollution [28, 29].

There have been only a few studies to date examining the effect of climate change alone on human health burdens from air quality; for PM2.5 studies have focussed on long-term exposure, whilst for O3 studies have considered either short-term or long-term exposure. Fang et al. [50] quantified the effect of climate change induced changes in PM2.5 and O3 air quality over the twenty-first century (2090s–1990s) under the moderate SRES A1B scenario on global premature mortalities due to long-term exposure. PM2.5 concentrations increases due to elevated sulphate concentrations and reduced precipitation over the major emission source regions, led to an increase in global annual premature mortality associated with chronic exposure to PM2.5 of approximately 100,000 deaths (95% confidence interval, CI, of 66–130,000) with corresponding years of life (YLL) lost increasing by nearly 900,000 (95% CI, 576,000–1,128,000) years [50]. Higher O3 in polluted regions also increased annual premature mortality due to respiratory disease from chronic O3 exposure by 6,300 deaths (95% CI, 1600–10,400) [50]. On average, across 50 U.S. cities, higher O3 under the SRES A2 high climate scenario increased total daily mortalities by 0.11–0.27% from 2000s to 2050s [83]. For the same period Tagaris et al. [84] estimated that climate change under the SRES A1B scenario increased combined PM2.5 (long-term exposure) and O3 (short-term exposure) related annual U.S premature mortalities by 4,300 deaths. Examining climate policies that reduced the global mean temperature change from 6 °C to ~1.5 °C produced ~50,000 avoided premature mortalities for the USA [45]. Over Europe, Orru et al. [85], estimated annual premature mortalities due to short-term exposure to O3 to increase over most of Europe but decrease over the northernmost Nordic and Baltic countries, with the largest change being a 34% increase over Belgium under the SRES A2 climate scenario in the 2050s, due to regional reductions in cloud cover and soil moisture. In a sensitivity study over the UK, Heal et al. [86] found that a 5 °C increase of year-round temperatures increased the total UK health burden due to short-term exposure to O3 by an additional 500 premature deaths (4%), assuming no change in population and no threshold for O3 effects.

Most recently, examining the climate change impacts only from the RCP 8.5 scenario from an ensemble of nine chemistry-climate models participating in the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP), Silva et al. [87] estimated 43,600 (95% CI: -195,000 to 237,000) global respiratory-related deaths due to long-term ozone exposure, and 215,000 (95% CI: -76,100 to 595,000) global deaths in 2100 relative to 2000 due to long-term PM2.5 exposure. For Europe, 2,890 (95% CI: -4680 to 15,800) ozone respiratory-related deaths and 9850 (95% CI: 4550 to 16,100) PM2.5 deaths due to climate change alone were estimated in 2100 compared to 2000.

Future climate and emission scenarios combined- air quality and health impacts

The attribution of future climate change on air quality can be difficult for several reasons: results are strongly influenced by the driving global climate model, simulations need to be of sufficient duration to separate climate change from climate variability, and the impacts of climate change on air pollution are likely to depend on the magnitudes of anthropogenic emission change [29, 82]. The majority of recent studies that consider both air-quality impacts from climate change as well as consequent health effects under the RCP scenarios typically consider combined emission and climate change, which are reviewed below. For the RCP scenarios, changes in global-mean temperature associated with changes in greenhouse gas emissions have been given in the previous section. All RCP scenarios assume strong abatement measures: NOx emissions are reduced by ~50% in 2100 (from ~80 Tg NO yr.−1 to 30–50 Tg NO yr.−1) compared to 2000 levels and black carbon (BC) emission also reduce by a similar percentage (see Fig. 1; [29]). These measures generally result in large decreases in pollutant precursor species globally [29]. However, the CH4 abundance more than doubles in 2100 compared to 2005 for the RCP 8.5 scenario whilst RCP 2.6 predicts a ~25% reduction (Fig. 1; [29]).

From the ACCMIP models, Young et al. [11] suggest annual-mean O3 increases of >10 ppbv over Europe (see their Fig. 9) under RCP 8.5 emissions and climate in 2100 compared to 2000. Over Europe, Langner et al. [80] studied air quality in 2100 under the SRES A1B climate scenario together with O3 precursor emission changes from the RCP 4.5 (4.5 W m−2 net radiative forcing at 2100) scenario. They found that in southern Europe projected emissions reductions more than offset the climate penalty or the increase in April–September daily max O3. In northern Europe, both emission reductions and climate change decreased O3. Coleman et al. [88] reported similar findings for the RCP 6.0 scenario with the most significant changes after 2050 due to the pattern of changing emissions. However, by 2100, changes in meteorology were found to be important over the North Atlantic region.

The combined effects of emission and climate changes under the RCP scenarios averaged over Europe based on IPCC AR5 [74] are shown in Fig. 3. By 2100, European multi-model annual-mean surface O3 changes between −15 to +2 ppbv relative to 2000 and PM2.5 changes between −4 to −6 μg m−3. The increase in O3 under RCP 8.5 reflects primarily the increase in CH4 emissions [29, 89], whilst the decreases in the other three scenarios reflect the role of emission reductions of other O3 precursors. PM changes depend on oxidant levels but generally follow SO2 emissions and primary organic carbon emissions reductions [29, 74]. All RCP scenarios suggest similar decreases in European-average PM2.5. Overall, the emissions changes strongly drive changes in O3 and PM2.5 in terms of annual-mean metrics. These are either augmented or reduced by the multiple effects of climate on atmospheric composition. However, as discussed above, for other metrics relating to peak exposure levels, the effects of changes in climate may be relatively more important.

Adaptation (with permission) of Figures 11.23a and 11.23b from chapter 11, IPCC WG1 Fifth Assessment Report (Kirtman et al. [74]), showing European panels only. Projected changes in annual-mean (left) O3 (ppbv) and (right) PM2.5 (μg m−3) from 2000 to 2100 following the RCP scenarios (8.5 red, 6.0 orange, light blue 4.5, 2.6 dark blue) averaged over Europe (land). Coloured lines show the average and shading denotes the full range of 4 chemistry-climate models and coloured dots and vertical bars represent the average and full range of ~15 ACCMIP models for decadal time slices centred on 2010, 2030, 2050 and 2100. The average value and model standard deviation for the reference period is shown in the top of each panel for CMIP5 models (left) and ACCMIP models (right). For further details, see Kirtman et al. [74]

Collette et al. [82] examined the effects of the RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 climate scenarios alongside compatible (but not RCP) emission scenarios on air quality in 2050 for both O3 and PM2.5. For both pollutants, they showed that the main factor driving future air quality projections for Europe was precursor emission changes, rather than climate change. A clear O3 climate penalty was found across most of Europe. The resulting change in population-weighted SOMO35 O3 health metric (defined as the annual sum of daily maximum 8 h running mean O3 over 35 ppbv) varied between +7% to −80% depending on the emission scenario whilst exposure-weighted PM2.5 was reduced by 62–78%. However, the authors point out the sensitivity to the emission scenarios used and to precipitation projections. Kim et al. [90] further note the potential of climate-related increases in natural NOx emissions from lightning and soils to offset anthropogenic NOx emission changes. Over the UK, greater O3 penalties from emissions changes compared to temperature change were also reported [86].

Most recently, Silva et al. [91] quantified premature morality related to O3 and PM2.5 long-term exposure, using ensemble-mean results from 14 ACCMIP models for the four RCPs for combined emissions and climate scenarios, additionally considering future population projections. Global excess O3-related (316,000 deaths/year in 2100) were found under the RCP8.5 but avoided O3-related respiratory mortalities (−718,000 to −1.02 million deaths/year) resulted from the other three RCP scenarios respectively, in line with their respective changes in O3 concentrations as described above. For RCP8.5, climate change was found to contribute 14% of the overall increase in global ozone mortality estimated in 2100 relative to 2000 [87]. Equivalent values for Europe were +2,390 (RCP 8.5) to −24,900 to −44,600 (other three RCP scenarios) annual avoided deaths in 2100. However, when the change in population between 2000 and 2100 was also considered, the global mortality burden of O3 increased from 382,000 deaths/yr. in 2000 to 1.1–2.4 million deaths/yr. in 2100 depending on RCP scenario [91]. Reduced global PM2.5 concentrations in all RCP scenarios led to global avoided premature mortalities ranging between −2.4 to −1.3 million deaths/yr. (for Europe: −103,000 to - 112,000 avoided premature mortalities in 2100) [91]. Under RCP 8.5, climate change countered the decrease in global PM2.5-related mortality by 16% in 2100 relative to 2000 [87]. Considering future PM2.5 concentrations and population change, the global mortality burden of PM2.5 decreased from 1.7 million deaths/yr. in 2000 to 0.95–1.55 million deaths/yr. in 2100 depending on RCP scenario [91]. Differences in simulated pollutant concentrations were highlighted as the major source of overall mortality uncertainty [87, 91].

Key exposure-related determinants on future air quality health burdens

The extent of adverse health impacts from exposure to surface O3 depends markedly on whether a threshold concentration of O3 below which no impact is assumed. A recent review by COMEAP [3] suggest no evidence of a threshold or a counter-factual concentration other than zero, yet the WHO [7] does recommend the use of a threshold of 70 μg m−3 due to greater availability of data in the warm season when lower values than this threshold are less prevalent, outside of highly polluted regions.

There are also uncertainties in the appropriate magnitude of risk coefficient to use, and the part of the year for which O3 exposure is relevant for health impacts [7]. Uncertainties in risk estimates were suggested to have a similar or greater magnitude of influence as model uncertainty in simulated O3 concentrations for assessing the health effects of O3 and black carbon [92, 93].

Issues concerning potential modification of air pollution health effects by temperature remain pertinent for future climate-related assessments [23, 30, 94, 95]. In addition, daily baseline mortality and morbidity rates may not remain constant in the future. However, it is not possible to predict changes in risk coefficients or threshold effects due to adaptation to future pollutant levels or to future climate change [96]. Finally, the effects of higher air pollution levels and air pollution episodes will undoubtedly be modified by behaviour that affects exposure, such as time indoors and exercise that affects inhalation.

Conclusions

There are numerous studies on future changes in air quality for surface O3 in particular, but very limited studies on the associated human health impacts. Globally, warming decreases background surface O3, but higher CH4 levels under the latest IPCC scenario RCP8.5 more than counteract this decrease, causing increased surface O3. Regionally, several studies suggest fairly robust climate change signals over Europe that lead to increases in summer-mean O3 in southern Europe and less change in northern Europe. The effects for higher concentration metrics such as daily maximum O3 are typically larger. For PM, studies related to climate change are still limited, and key uncertainties arise due to the differing effects of temperature on various PM components and uncertainties in future precipitation patterns. Further studies that examine the effects of climate change on PM would be beneficial.

There is consensus in the literature that, in the near term, air quality will be dominated by emission changes rather than changes in climate and/or long-range transport. However, for peak concentrations and longer future horizons the effect of the latter two processes may be much more relevant. The latest RCP scenarios show the strong influence of future CH4 levels on air quality. Controlling CH4 and possibly black carbon are viewed as win-win policies for mitigating air quality as well as climate change [97,98,99] and greenhouse gas policies have been related to human health benefits [100, 101].

Extreme air pollution episodes are associated with changing weather patterns, such as heat waves and stagnation episodes. A number of studies of the 2003 heatwave in Europe have identified various mechanisms associated with climate change that have a substantial effect on O3 and PM air quality. Air pollution episodes are more generally related to stagnation events which may in turn be related to larger-scale blocking and influenced by climate change. Studies that link changes in climate extremes to changes in air pollution characteristics (e.g., episode length and frequency, changes in high percentile values) are needed to quantify the effect of changes in climate extremes on air quality.

Key uncertainties in mechanistic understanding limit our confidence in future projections of air quality and air quality episodes. A major uncertainty for O3 and PM is the opposing influences of rising temperature and CO2 on natural isoprene emissions. The impact of climate change on transport pathways is also highly uncertain and model dependent. For example, projected changes in the frequency of regional air stagnation events remain difficult to assess.

Overall, the climate penalty effects on O3 and possibly PM indicates that stronger emission controls will be needed in the future to avoid higher health risks associated with climate change induced worsening of air quality in populated regions [50]. For O3-related health impacts, major uncertainties, besides model uncertainty in simulated O3 levels, are the impacts of long-term exposure, thresholds and effect modification by temperature. For PM-related health impacts, model-to-model variability in the response of PM2.5 concentrations to climate change seems likely to be the largest source of uncertainty. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in risk estimates for O3 and PM are also an issue for modelling health impacts. Finally, there is uncertainty regarding future potential adaptation effects into the twenty-first century.

Open peer review

Peer review reports for this article are available in Additional file 1.

References

WHO, 2013a. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution – REVIHAAP project: technical report, World Health Organisation, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2013 http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/air-quality/publications/2013/review-of-evidence-on-health-aspects-of-air-pollution-revihaap-project-final-technical-report. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Ren C, Tong S. Health effects of ambient air pollution – recent research development and contemporary methodological challenges. Environ Health. 2008;7:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-7-56.

COMEAP (2015) Quantification of Mortality and Hospital Admissions Associated with Ground-level Ozone, UK Department of Health Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution. ISBN 978–0–85951-776-8. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/comeap-quantification-of-mortality-and-hospital-admissionsassociated-with-ground-level-ozone. Accessed 27 May 2016.

EEA. Air quality in Europe - 2016 report. EEA Report No 28/2016., European Environment Agency. 2014. ISBN: 978–92–9213-824-0. http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2016. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, Anderson HR, Bhutta ZA, Biryukov S, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2013;2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(1659–1724):2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8.

EEA. Air quality in Europe - 2014 report. EEA Report No 5/2014., European Environment Agency. 2014. ISBN: 978–92–9213-490-7. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2014. Accessed 27 May 2016.

WHO, 2013b, Health risks of air pollution in Europe –HRAPIE project. Recommendations for concentration–response functions for cost–benefit analysis of particulate matter, ozone and nitrogen dioxide. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/air-quality/publications/2013/health-risks-of-air-pollution-in-europe-hrapie-project.-recommendations-for-concentrationresponse-functions-for-costbenefit-analysis-of-particulate-matter,-ozone-and-nitrogen-dioxide. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Katsouyanni K, Samet JM, Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Le Tertre A, Medina S, et al. Air pollution and health: a European and north American approach (APHENA). Research report 142. Boston: Health Effects Institute; 2009. http://pubs.healtheffects.org/view.php?id=327. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Hughes E, Shi YL, Turner MC, Pope CA, Thurston G, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Extended follow-up and spatial analysis of the American Cancer Society study linking particulate air pollution and mortality. https://www.healtheffects.org/publication/extended-follow-and-spatial-analysis-american-https://www.healtheffects.org/publication/extended-follow-and-spatial-analysis-americancancer-society-study-linking-particulate. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Pope CA, Ito K, Thurston G, Krewski D, Shi YL, Calle E, Thun M. Long- term ozone exposure and mortality. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1085–95.

Young PJ, Archibald AT, Bowman KW, Lamarque JF, Naik V, Stevenson DS, et al. Pre-industrial to end 21st century projections of tropospheric ozone from the atmospheric chemistry and climate model Intercomparison project (ACCMIP). Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:2063–90. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2063-2013.

Jacobson, MZ., 2002, Atmospheric pollution: history, science and regulation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and USA, http://web.stanford.edu/group/efmh/jacobson/POLbook/POLbook.html. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Jacob, DJ, 1999, Introduction to atmospheric chemistry, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA: http://acmg.seas.harvard.edu/people/faculty/djj/book/. Accessed 27 May 2016.

Patz JA, Frumkin H, Holloway T, Vimont DJ, Haines A. Climate change challenges and opportunities for Global Health. J Amer Med Assoc. 2014;312:1565–80.

Lee JD, Lewis AC, Monks PS, Jacob M, Hamilton JF, Hopkins JR, et al. Ozone photochemistry and elevated isoprene during the UK heatwave of august 2003. Atmos Environ. 2006;40:7598–613.

Solberg S, Hov O, Sovde A, Isaksen ISA, Coddeville P, De Backer H, Forster C, Orsolini Y, Uhse K. European surface ozone in the extreme summer 2003. J Geophys Res. 2008;113(D07307) https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD009098.

Vieno M, Dore AJ, Stevenson DS, Doherty R, Heal MR, Reis S, et al. Modelling surface ozone during the 2003 heat-wave in the UK. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:7963–78. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-7963-2010.

Francis XV, Chemel C, Sokhi RS, Norton EG, Ricketts HMA, Fisher BEA. Mechanisms responsible for the build-up of ozone over south East England during the august 2003 heatwave. Atmos Environ. 2011;45(38):6880–90.

Hodzic A, Madronich S, Bohn B, Massie S, Menut L, Wiedinmyer C. Wildfire particulate matter in Europe during summer 2003: meso-scale modeling of smoke emissions, transport and radiative effect. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:4043–64.

Stedman JR. The predicted number of air pollution related deaths in the UK during the august 2003 heatwave. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:1087–90.

Johnson H, Kovats S, McGregor G, Stedman J, Gibbs M, Walton H. The impact of the 2003 heat wave on daily mortality in England and Wales and the use of rapid weekly mortality estimates. Euro Surveill. 2005;10(7):558.

Fischer PH, Brunekreef B, Lebret E. Air pollution related deaths during the 2003 heat wave in the Netherlands. Atmos Environ. 2003;38:1083–5.

Filleul L, Cassadou S, Medina S, Fabres P, Lefranc A, Eilstein D, et al. The relation between temperature, ozone, and mortality in nine French cities during the heat wave of 2003. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1344–7. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8328.

Beniston M. The 2003 heat wave in Europe: a shape of things to come? An analysis based on Swiss climatological data and model simulations. Geophys Res Lett. 2004;31:L02202. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018857.

Scḧar C, Vidale PL, L̈uthi D, Frei C, Ḧaberli C, Liniger MA, Appenzeller C. The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature. 2004;427:332–6.

Stott PA, Stone DA, Allen MR. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature. 2004;432:610–4.

Isaksen ISA, Granier C, Myhre G, Berntsen TK, Dalsoren SB, Gauss M, et al. Atmospheric composition change: climate-chemistry interactions. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:5138–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.08.003.

Jacob DJ, Winner DA. Effect of climate change on air quality. Atmos Environ. 2009;43:51–63.

Fiore AM, Naik V, Spracklen DV, Steiner A, Unger N, Prather M, et al. Global air quality and climate. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:6663–83.

Pattenden S, Armstrong BG, Milojevic A, Heal MR, Chalabi Z, Doherty R, Barratt B, Kovats RS, Wilkinson P. Ozone, heat and mortality: acute effects in 15 British conurbations. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:699–707.

Cox WM. Chu S-H assessment of interannual ozone variation in urban areas from a climatological perspective. Atmos Environ. 1995;30:2615–25.

Sillman S, Samson PJ. The impact of temperature on oxidant formation in urban, polluted rural and remote environments. J Geophys Res. 1995;100(D7):11497–508. https://doi.org/10.1029/94JD02953.

Racherla PN, Adams PJ. The response of surface ozone to climate change over the eastern United States. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8:871–85. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-871-2008.

Doherty RM, Wild O, Shindell DT, Zeng G, MacKenzie IA, Collins WJ, Fiore AM, Stevenson DS, Dentener FJ, Schultz MG, Hess P, Derwent RG, Keating TJ. Impacts of climate change on surface ozone and intercontinental ozone pollution: a multi-model study. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2013;118 https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50266.

Rosenstiel TN, Potosnak MJ, Griffin KL, Fall R, Monson RK. Increased CO2 uncouples growth from isoprene emission in an agriforest ecosystem. Nature. 2003;421:256–9.

Arneth A, Miller PA, Scholze M, Hickler T, Schurgers G, Smith B, Prentice IC. CO2 inhibition of global terrestrial isoprene emissions: potential implications for atmospheric chemistry. Geophys Res Lett. 2007;34:L18813. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030615.

Heald CL, Wilkinson MJ, Monson RK, Alo CA, Wang GL, Guenther A. Response of isoprene emission to ambient CO2 changes and implications for global budgets. Glob Change Biol. 2009;15(5):1127–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01802.x.

Young PJ, Arneth A, Schurgers G, Zeng G, Pyle JA. The CO2 inhibition of terrestrial isoprene emission significantly affects future ozone projections. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:2793–803.

Pacifico F, Folberth GA, Jones CD, Harrison SP, Collins WJ. Sensitivity of biogenic isoprene emissions to past, present, and future environmental conditions and implications for atmospheric chemistry. J Geophys Res. 2009;117:D22302. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JD018276.

Squire OJ, Archibald AT, Abraham NL, Beerling DJ, Hewitt CN, Lathière J, Pike RC, Telford PJ, Pyle JA. Influence of future climate and cropland expansion on isoprene emissions and tropospheric ozone. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:1011–24.

Ito A, Sillman S, Penner JE. Global chemical transport model study of ozone response to changes in chemical kinetics and biogenic volatile organic compounds emissions due to increasing temperatures: sensitivities to isoprene nitrate chemistry and grid resolution. J Geophys Res. 2009;114:D09301. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011254.

O’Connor FM, Boucher O, Gedney N, Jones CD, Folberth GA, Coppell R, et al. Possible role of wetlands, permafrost, and methane hydrates in the methane cycle under future climate change: a review. Rev Geophys. 2010, RG4005;48 https://doi.org/10.1029/2010RG000326.

Forkel R, Knoche R. Regional climate change and its impact on photooxidant concentrations in southern Germany: simulations with a coupled regional climate-chemistry model. J Geophys Res. 2006;111:D12302. doi:10.1029/2005JD006748.

Hedegaard GB, Brandt J, Christensen JH, Frohn LM, Geels C, Hansen KM, Stendel M. Impacts of climate change on air pollution levels in the northern hemisphere with special focus on Europe and the Arctic. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8:3337–67. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-3337-2008.

Garcia-Menendez F, Saari RK, Monier E, Selin NE, U.S. Air quality and health benefits from avoided climate change under greenhouse gas mitigation. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:7580–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b01324.

Racherla PN, Adams PJ. Sensitivity of global tropospheric ozone and fine particulate matter concentrations to climate change. J Geophys Res. 2006;111(D24103), doi:10.1029/2005JD006939.

Pye HOT, Liao H, Wu S, Mickley LJ, Jacob DJ, Henze DK, Seinfeld JH. Effect of changes in climate and emissions on future sulfate-nitrate-ammonium aerosol levels in the United States. J Geophys Res. 2009;114(D01205), doi:10.1029/2008JD010701.

Dawson JP, Adams PJ, Pandis SN. Sensitivity of PM2.5 to climate in the eastern US: a modeling case study. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:4295–309. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4295-2007.

Johnson CE, Collins WJ, Stevenson DS, Derwent RG. Relative roles of climate and emissions changes on future oxidant concentrations. J Geophys Res. 1999;104(D15):18631–45. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900204.

Fang Y, Mauzerall DJ, Liu J, Fiore AM, Horowitz LW. Impacts of 21st century climate change on global air pollution-related premature mortality Climatic Change. 2013;121:239–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0847-8.

Fang Y, Fiore AM, Horowitz LW, Gnanadesikan A, Held I, Chen G, Vecchi G, Levy H. The impacts of changing transport and precipitation on pollutant distributions in a future climate. J Geophys Res. 2011;116(D18):D18303. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jd015642.

Penrod A, Zhang Y, Wang K, Wu SY, Leung L. Impacts of future climate and emission changes on US air quality. Atmos Environ. 2014;89:533–47.

Allen RJ, Landuyt W, Rumbold ST. An increase in aerosol burden and radiative effects in a warmer world. Nat Clim Chang. 2016;6:269–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2827.

Held IM, Soden BJ. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J Clim. 2006;19:5686–99. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3990.1.

Liu C, Allan RP. Observed and simulated precipitation responses in wet and dry regions 1850–2100. Environ Res Lett. 2013;8:034002.

Meleux F, Solmon F, Giorgi F. Increase in summer European ozone amounts due to climate change. Atmos Environ. 2007;41(35):7577–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.05.048.

Kunkel KE, Huang HC, Liang XZ, Lin JT, Wuebbles D, Tao Z, Williams A, Caughey M, Zhu J, Hayhoe K. Sensitivity of future ozone concentrations in the northeast U.S. to U.S. regional climate change. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang. 2008;13:597–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9137-y.

Katragkou E, Zanis P, Kioutsioukis I, Tegoulias I, Melas D, Krüger BC, Coppola E. Future climate change impacts on summer surface ozone from regional climate-air quality simulations over Europe. J Geophys Res. 2011;116(D22307) https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD015899.

Hauglustaine DA, Lathiere J, Szopa S, Folberth GA. Future tropospheric ozone simulated with a climate-chemistry-biosphere model. Geophys Res Lett. 2005;32(L24807) https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL024031.

Banerjee A, Archibald AT, Maycock AC, Telford P, Abraham NL, Yang X, Braesicke P, Pyle JA. Lightning NOx, a key chemistry–climate interaction: impacts of future climate change and consequences for tropospheric oxidising capacity. Atmos Chem Phys. 2014;14:9871–81. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9871-2014.

Finney DL, Doherty RM, Wild O, Abraham LN, Young P. Response of lightning NOx and ozone production to climate change: insights from the atmospheric chemistry and climate model Intercomparison project (ACCMIP). Geophys Res Letts. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL068825.

Butchart N, Scaife AA. Removal of chlorofluorocarbons by increased mass exchange between the stratosphere and troposphere in a changing climate. Nature. 2001;410:799–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/35071047.

Collins WJ, Derwent RG, Garnier B, Johnson CE, Sanderson MG, Stevenson DS. Effect of stratosphere-troposphere exchange on the future tropospheric ozone trend. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D12):8528. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002617.

Lacressonnière G, Peuch VH, Vautard R, Arteta J, Deque M, Joly M, Josse B, Marcal V, Saint-Martin D. European air quality in the 2030s and 2050s: impacts of global and regional emission trends and of climate change. Atmos Environ. 2014;92:348–58.

Mickley LJ, Jacob DJ, Field BD, Rind D. Effects of future climate change on regional air pollution episodes in the United States. Geophys Res Lett. 2004;31(L24103) https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL021216.

Murazaki K, Hess P. How does climate change contribute to surface ozone change over the United States? J Geophys Res. 2006;111:D05301. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD005873.

Wu S, Mickley LJ, Jacob DJ, Rind D, Streets DG. Effects of 2000-2050 changes in climate and emissions on global tropospheric ozone and the policy-relevant background surface ozone in the United States. J Geophys Res 2008a;113, doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD009639.

Wu S, Mickley LJ, Leibensperger EM, Jacob DJ, Rind D, Streets DG. Effects of 2000-2050 global change on ozone air quality in the United States, J Geophys Res 2008b;113, doi:https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008917.

Glotfelty T, Zhang Y, Karamchandani P, Streets DG. Will the role of intercontinental transport change in a changing climate? Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;14:9379–402.

Barnes EA, Fiore AM. Surface ozone variability and the jet position: implications for projecting future air quality. Geophys Res Lett. 2013;40:2839–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50411.

Masato G, Hoskins BJ, Woollings TJ. Winter and summer northern hemisphere blocking in CMIP5 models. J Clim. 2013;26:7044–59. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00466.1.

Webber CP, Dacre HF, Collins WJ, Masato G. The dynamical impact of Rossby wave breaking upon UK PM10 concentration. Atmos Chem Phys. 2017;17:867–81. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-867-2017.

Horton DE, Skinner CB, Singh D, Diffenbaugh NS. Occurrence and persistence of future atmospheric stagnation events. Nat Clim Chang. 2014;4:698–703. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE2272.

Kirtman B, Power SB, et al. Near-term climate change: projections and predictability. In: climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Stocker T.F., et al., (eds.)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. 2013.

Nakicenovic N, et al. Special report on emission scenarios (SRES) report of working group III of the intergovernmental panel on change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. 2000.

Collins M, Knutti R, Arblaster J, Dufresne J-L, Fichefet T, Friedlingstein P, Gao X, Gutowski, WJ, Johns T, Krinner G, Shongwe M, Tebaldi C, Weaver AJ, Wehner M. Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. In: Climate Change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Stocker T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2013.

Bloomer BJ, Stehr JW, Piety CA, Salawitch RJ, Dickerson RR. Observed relationships of ozone air pollution with temperature and emissions. Geophys Res Lett. 2009;36:L09803. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL037308.

Rasmussen D, Hu J, Mahmud A, Kleeman MJ. The ozone-climate penalty: past, present, and future. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:14258–66.

Colette A, Andersson C, Baklanov A, Bessagnet B, Brandt J, Christensen JH, Doherty R, Engardt M, Geels C, Giannakopoulos C, Hedegaard GB, Katragkou E, Langner J, Lei H, Manders A, Melas D, Meleux F, Rouil L, Sofiev M, Soares J, Stevenson DS, Tombrou-Tzella M, Varotsos KV, Young P. Is the ozone climate penalty robust in Europe? Environ Res Lett. 2015;10:084015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/8/084015.

Langner J, Engardt M, Andersson C. European summer surface ozone 1990-2100. Atmos Chem Physics. 2012a;12:10097–105.

Langner J, Engardt M, Baklanov A, Christensen JH, Gauss M, Geels C, Hedegaard GB, Nuterman R, Simpson D, Soares J, Sofiev M, Wind P, Zakey A. A multi-model study of impacts of climate change on surface ozone in Europe. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012b;12:10423–40.

Colette A, Bessagnet B, Vautard R, Szopa S, Rao S, Schucht S, Klimont Z, Menut L, Clain G, Meleux F, Curci G, Rouïl L. European atmosphere in 2050, a regional air quality and climate perspective under CMIP5 scenarios. Atmos Chem Physics. 2013;13:7451–71. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-7451-2013.

Bell ML, Goldberg R, Hogrefe C, Kinney P, Knowlton K, Lynn B, Rosenthal J, Rosenzweig C, Patz J. Climate change, ambient ozone, and health in 50 US cities. Clim Chang. 2007;82(1–2):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9166-7.

Tagaris E, Liao K-J, DeLucia AJ, Deck L, Amar P, Russell AG. Potential impact of climate change on air pollution-related human health effects. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(13):4979–88. https://doi.org/10.1021/es803650w.

Orru H, Andersson C, Ebi KL, Langner J, Astrom C, Forsberg B. Impact of climate change on ozone-related mortality and morbidity in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:285–94. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00210411.

Heal MR, Heaviside C, Doherty RM, Vieno M, Stevenson DS, Vardoulakis S. Health burdens of surface ozone in the UK for a range of future scenarios. Environ Int. 2013;61:36–42.

Silva, RA, West, JJ, Lamarque, J.-F, Shindell, DT, Collins, S, Faluvegi, G, Folberth, G, Horowitz, LW, Nagashima, T, Naik, V, Rumbold, ST, Sudo, K, Takemura, T, Bergmann, D, Cameron-Smith, P, Doherty, RM, Josse, B, MacKenzie, IA, Stevenson, DS, Zeng, G. Future global mortality from changes in air pollution attributable to climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3354.

Coleman L, Martin D, Varghese S, Jennings SG, O'Dowd CD. Assessment of changing meteorology and emissions on air quality using a regional climate model: impact on ozone. Atmos Environ. 2013;69:198–210.

Wild O, Fiore AM, Shindell DT, Doherty RM, Collins WJ, Dentener FJ, Schultz MG, Gong S, MacKenzie IA, Zeng G, Hess P, Duncan BN, Bergmann DJ, Szopa S, Jonson JE, Keating TJ, Zuber A. Modelling future changes in surface ozone: a parameterized approach. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:2037–54. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-2037-2012.

Kim MJ, Park RJ, Ho CH, Woo JH, Choi KC, Song CK, Lee JB. Future ozone and oxidants change under the RCP scenarios. Atmos Environ. 2015;101:103–15.

Silva RA, West JJ, Lamarque J-F, Shindell DT, Collins WJ, Dalsoren S, Faluvegi G, Folberth G, Horowitz LW, Nagashima T, Naik V, Rumbold ST, Sudo K, Takemura T, Bergmann D, Cameron-Smith P, Cionni I, Doherty RM, Eyring V, Josse B, IA MK, Plummer DS, Righi M, Stevenson DS, Strode S, Szopa S, Zeng G. The effect of future ambient air pollution on human premature mortality to 2100 using output from the ACCMIP model ensemble. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16:9847–62. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-9847-2016.

Anenberg SC, West JJ, Fiore AM, Jaffe DA, Prather MJ, Bergmann D, Cuvelier K, Dentener FJ, Duncan BN, Gauss M, Hess P, Jonson JE, Lupu A, MacKenzie IA, Marmer E, Park RJ, Sanderson MG, Schultz M, Shindell DT, Szopa S, Vivanco MG, Wild O, Zeng G. Intercontinental impacts of ozone air pollution on human mortality. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:6482–7.

Anenberg SC, Talgo K, Arunachalam S, Dolwick P, Jang C, West JJ. Impacts of global, regional, and sectoral black carbon emission reductions on surface air quality and human mortality. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:7253–67. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-7253-2011.

Ren C, Williams GM, Mengersen K, Morawska L, Tong S. Does temperature modify short-term effects of ozone on total mortality in 60 large eastern US communities?—an assessment using the NMMAPS data. Environ Int. 2008;34:451–8.

Atkinson RW, Yu D, Armstrong BG, Pattenden S, Wilkinson P, Doherty RM, Heal MR, Anderson HR. Concentration response function for ozone and daily mortality: results from five urban and five rural U.K. Populations, Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1411–7.

Knowlton K, Rosenthal JE, Hogrefe C, Lynn B, Gaffin S, Goldberg R, Rosenzweig C, Civerolo K, Ku JY, Kinney PL. Assessing ozone-related health impacts under a changing climate. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1557–63.

UNEP/WMO. UNEP/WMO Integrated Assessment of Black Carbon and Tropospheric Ozone. 2011; https://wedocs.unep.org/rest/bitstreams/12809/retrieve.

Shindell D, Kuylenstierna JCI, Vignati E, van Dingenen R, Amann M, Klimont Z, et al. Simultaneously mitigating near-term climate change and improving human health and food security. Science. 2012;335:183–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1210026.

Baker LH, Collins WJ, Olivié DJL, Cherian R, Hodnebrog Ø, Myhre G, Quaas J. Climate responses to anthropogenic emissions of short-lived climate pollutants. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15:8201–16. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-8201-2015.

Bell ML, Davis DL, Cifuentes LA, Krupnick AJ, Morgenstern RD, Thurston GD. Ancillary human health benefits of improved air quality resulting from climate change mitigation. Environ Health. 2008;7:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-7-41.

Remais JV, Hess JJ, Ebi KL, Markandya A, Balbus JM, Wilkinson P, Haines A, Chalabi Z. Estimating the health effects of greenhouse gas mitigation strategies: addressing parametric, model, and valuation challenges. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:447–55. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1306744.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yuanyuan Fang, Department of Global Ecology, Carnegie Institution For Science, Stanford University for her advice in key areas. All authors acknowledge the UK research councils Living with Environmental Change (LWEC) program for funding and Dr. Sari Kovats, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and LWEC fellow, for guidance and advice. RMD and MRH also acknowledge the cross UK-research councils Environmental Exposure and Human Health Initiative grant NE/I008063/1. FMO’C is also supported by the Joint UK DECC/Defra Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme (GA01101).

This paper is an updated and reduced version of a technical paper provided in support of a Health Report Card produced for the UK Living With Environmental Change (LWEC) Network.

Funding

Publication of this article was funded by the UK Living With Environmental Change (LWEC) Network. LWEC was succeeded in 2016 by the Research and Innovation for our Dynamic Environment (RIDE) Forum (http://www.nerc.ac.uk/research/partnerships/ride/).

Availability of data and materials

Not Applicable.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Environmental Health Volume 16 Supplement 1, 2017: Special Issue on the impact of climate change on health in the UK. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://ehjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-16-supplement-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors wrote the manuscript text for the original technical paper on which this review is based. RMD, FMO’C and MRH contributed to the design of this paper and RMD revised the draft of this final manuscript with assistance from FMO’C and MRH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

No competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Open peer review. (PDF 161 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Doherty, R.M., Heal, M.R. & O’Connor, F.M. Climate change impacts on human health over Europe through its effect on air quality. Environ Health 16 (Suppl 1), 118 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0325-2

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0325-2