Abstract

Introduction

Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) have been largely used in the world during the past decades, since they are known for enhancing children’s human development and promoting social inclusion for the most deprived groups. In other words, CCTs seek to create life chances for children to overcome poverty and exclusion, thus reducing inequality of opportunity. The main goal of the present article is to identify studies capable of showing if CCTs create equality of opportunity in health for children in low and middle-income countries.

Methodology

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in the Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), PubMed/Medline, Scopus and Web of Science electronic bibliographic databases. Relevant studies were searched using the combination of key words (either based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms or free text terms) related to conditional cash transfers, child health and equality of opportunity. An integrative research review was conducted on 17 quantitative studies.

Results

The effects of CCTs on children’s health outcomes related to Social Health Determinants were mostly positive for immunization rates or vaccination coverage and for improvements in child morbidity. Nevertheless, the effects of CCTs were mixed for the child mortality indicators and biochemical or biometric health outcomes.

Conclusions

The present literature review identified five CCTs that provided evidence regarding the creation of health opportunities for children under 5 years old. Nevertheless, cash transfers alone or the use of conditions may not be able to mitigate poverty and health inequalities in the presence of poor health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) are regular money transfers to poor households given under conditions related to the use of health services, the uptake of food and nutritional supplementation, the enrollment and attendance of children and adolescents in school [1]. CCTs were initially implemented in Mexico, Brazil and Bangladesh in the 1990s, but they have been largely used in the world during the past decades, including programs initiated in more advanced economies such as the US [2].

Their success is based on the assumption that they are able to enhance children’s human development [3] through improvements of health and schooling of poor and vulnerable children, contributing to breaking the intergenerational poverty cycle [4] and social inclusion of the deprived groups [5]. In other words, CCTs seek to create life chances for children to overcome poverty and exclusion, thus reducing inequality of opportunity.

Inequality of opportunity in health and CCTs

Inequality of opportunity is concerned with the outcome disparities sourced by factors considered unfair which are defined as circumstances exogenous to the individuals [6, 7], such as parental socioeconomic characteristics, financial hardships in early childhood, and birth characteristics which include sex, race and ethnicity [8, 9]. From this perspective, individuals with the same circumstances are aggregated into social groups that indicate a situation in which some are more privileged than others. Therefore, equality of opportunity is achieved when opportunities between social groups are equally distributed [7], so their differences in outcome are not influenced by circumstances, but from individual aspects alone [8].

For the specific case of health, inequality of opportunity is related to what is known as health inequities. This concept defines that avoidable inequalities in health are fueled by the Social Determinants of Health (SDH), which are “the conditions in which individuals are born, grow, work, live, and age” [10]. Health inequalities sourced by SDH are seen as the root for the great discrepancies in health status in the world [11], demanding the increase of equitable initiatives [12] such as CCTs.

Purpose and context of the present study

The main goal of the present study is to identify studies capable of showing if CCTs create equality of opportunity in health for children under 5 years in low and middle-income countries. Our research question is “Do CCTs promote equality of opportunity in health for children under five years old in low and middle- income countries?”.

We focus on the specific case of child health because it remains a major public health concern in low and middle-income regions [3]. In addition, children in the first 5 years of life living in these countries usually face multiple health risks [13], which can hamper child development and negatively influence an individual’s life course [14]. For this reason, CCTs seems to be an effective social intervention capable of addressing immediate and underlying causes of poor child health, since they have presented positive effects in the use of healthcare services and income deprivation by beneficiary children [15]. Hence, the provision of better access to health by CCTs should create equality of opportunity in health if they reduce the influence of health inequities on the health outcomes of vulnerable groups, especially the younger generations.

Finally, studies concerning inequality of opportunity in health have been usually explored in more developed settings [16], but since CCTs have emerged as a key equitable policy in low and middle- income countries [2], it is time to understand if these programs create equality of opportunity in health for children in these locations.

Methods

An integrative literature review was conducted with the purpose to comprehend if CCTs create equality of opportunity in health for children. Differently from other types of reviews, this method discusses and summarizes a particular topic, contributing to theory development and influencing practice and policymaking [17] An integrative research review was conducted because a meta-analysis was not feasible due to the heterogeneity of the studies.

Eligibility criteria

For the purpose of the present study, the promotion of equality of opportunity in health is identified when there are improvements in health outcomes of children under 5 years old related to SDH and enrolled in a CCT program. We identified the SDH during the phase of the full-article reading.

We defined eligible health outcomes to be: (i) biochemical or biometric health outcomes with recognized relationships to illnesses or health conditions, such as height, weight, BMI, hemoglobin A1C, etc. (ii) measures of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity and mortality; (iii) reported general health status, and (iv) utilization of health services.

We focused specifically on children from 0 to 5 years old since this life stage is critical for child development and life course [13]. Therefore, studies focusing on the effects of CCTs on the health of children from 5 to 9 years old, adolescent health, adult health and elderly people’s health were excluded. Low and middle-income countries were classified according to the cut-off criteria proposed by the World Bank [18].

Studies have been published between January of 2006 and June of 2016 in English, Portuguese and Spanish, with quantitative or mixed methods. Qualitative work, case reports, conference papers, book chapters, books, study protocols, papers not including original data such as editorials, letters to the editor and commentaries were excluded. The same applies to the studies that were not published as full reports. Thirteen reviews were retrieved from our search, but they were excluded since they did not present any results specifically for our targeted ages, did not have any of our desired child health outcomes or the results were included in a larger revision of financial incentive programs in health, so we were unable to separate their effects from other interventions.

We have included only peer-reviewed work, so no gray literature was considered. Nevertheless, in the case where we could not access the original study from databases, we considered a previous version of the article available online as a working or discussion paper. In the end, only two studies could not be accessed.

Search methods for identification of studies

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in the electronic bibliographic databases Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), PubMed/Medline, Scopus and Web of Science. Relevant studies were searched using the combination of key words (either based on MeSH terms or free text terms) related to conditional cash transfer, child health and equality of opportunity.

In addition, studies were also identified through consulting selected articles’ references lists. More detailed description of the search terms is available in Additional file 1.

Data collection and analysis

The literature selection process was based on screening the title and abstract of the searched results. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a full-article reading was conducted in order to identify eligible articles. During this stage, additional literature was identified through consulting selected articles’ references lists. The flow of studies through the selection process is detailed in Fig. 1 according to Prisma guidelines [19].

Two researchers [RCBS and LBAM] screened all titles and abstracts and also participated in the selection process. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion by these two researchers, until agreement on inclusion or exclusion of the study was reached. The final sample contained articles that had classified data according to methodological research design, CCT program, country and related children’s health outcomes in Table 1.

Results

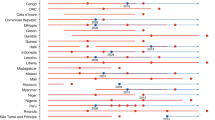

The literature search resulted in 1443 papers, including empirical and theoretical studies. During the second phase of the literature selection process, 114 articles were fully screened, and 17 articles were selected for analysis after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The majority of selected articles focused on CCTs programs located in Latin America (n = 13) following studies about CCTs based in Asia (n = 3) and Africa (n = 1) (Table 1). Moreover, the majority of the articles were delineated as quasi-experimental and experimental study designs (n = 8) and six papers were classified as observational studies. There were also studies that used a mixed ecological design, combining an ecological multiple-group design with a time-trend design (n = 3) (Table 1).

The articles presented studies of five CCT initiatives. Eighty two percent of the articles presented CCTs programs (n = 14) focused in alleviating household immediate poverty and in improving children’s health or/and schooling status by transferring cash to participants under the condition of children’s school attendance, health visits and, in some cases, the attendance of health education talks (Table 2). The remaining articles (n = 3) were based on the Janani Suraksha Yojana program, a CCT designed to prevent maternal and neonatal mortality by providing cash to vulnerable women at the time of delivery (Table 2).

In regard to the health outcomes presented, the majority of the studies have presented biochemical or biometric health outcomes, including height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-height and BMI-for-age in z-scores, birth weight, prevalence of stunting, wasting, overweight and hemoglobin concentration (n = 9). For the case of morbidity, one study used the incidence of diarrhea and acute respiratory infections, while six papers focused on child mortality indicators (perinatal, infant, neonatal and one-day mortality). In the case of health care services utilization, child immunization and vaccination coverage were mainly adopted in the studies selected for our final sample.

Although the majority of the studies reported poverty as the main children’s vulnerability for participating in a CCT program (n = 16), it was possible to identify other SDHs in the households of the beneficiaries, impacting the conditions in which their children are born, grow, work, live and age [10].

Households that were CCT beneficiaries were associated with lower educational level for one or both parents or the head of household (n = 5). CCT participants were also likely to live in an underprivileged location (n = 5), such as rural areas and minority groups regions. Gender issues (n = 1) were also associated with participants, including the existence of more female-headed households. Other SDHs of the participants were related to age (elderly-headed households, older women and child-headed households), race and ethnicity, coping with people with illness and disabilities and having or being an orphan in the household (Table 1).

The effects of CCTs on children’s health outcomes under the cited SDH were mostly positive. Studies that used immunization rates or vaccination coverage reported that CCT programs “led to a significant increase in childhood immunization rates” especially in high-priority locations (most vulnerable) in India [20] and the vaccination coverage increased more than 95% in Nicaragua for “children who live further away from a health facility or whose mothers are less educated” [21]. In Africa, the CCT arm of the randomized trial of a cash transfer program in Zimbabwe also showed an increase in up-to-date vaccination for children under 5 years old [22]. Improvements in child morbidity were also reported in Mexico where the incidence of diarrhea and acute respiratory infections has been reduced because of the participation in the CCT [23]. In the case of diarrhoeal diseases, the program had a significant positive effect among children in the most deprived households [23].

Nevertheless, the effects of CCTs were mixed for the child mortality indicators and biochemical or biometric health outcomes. Many of the CCTs in the present study reported reduction of infant, perinatal and postnatal mortality [24,25,26,27]. In Mexico, for example, larger reductions in neonatal and infant mortality were among groups with higher illiteracy rates and reduced access to electricity [24]. Studies concerning CCTs in India had conflicting results for the same indicators [20, 28]. The main explanation for this may be the difference in study designs and methods of these papers [20].

Biochemical or biometric health outcomes had also shown opposite results. In the case of Bolsa Familia, children enrolled in the program were more likely to have normal height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores than non-beneficiaries, being both groups from impoverished areas [29]. Nonetheless, two other assessments of nutritional outcomes for children under 5 years old showed that no significant differences were found for underweight and stunting between children participants and non- participants of this CCT program [30]. These indicators were also not different from the child population of Brazil [31]. In both studies, authors prompted for more actions in health education in order to enhance population awareness of better food and nutrition practices.

Discussion

The present integrative review was conducted in order to investigate if CCT programs create equality of opportunity in health for children under 5 years old. This particular life stage was chosen because it is critical for human development [13], which is the main purpose of traditional CCT programs. In order to identify the creation of equality of opportunity in health the present study applied Roemer’s conceptual framework of equality of opportunity and its capacity to mitigate the effects of unfair inequalities on health outcomes [6].

Although the selected studies applied a myriad of approaches and broad definitions for SDH, the literature review identified some trends in the creation of equality of opportunity in health for children by CCTs. First, we identified that CCTs created health opportunities for children because there were improvements in the health status of children with a vulnerable SDH. Nevertheless, creation of equality of opportunity in health for children was more reliable in quasi-experimental and experimental studies, considering that these study designs are more able to reduce causality bias.

In addition to this, it should be noticed that differences in the implementation phase, features and contexts of CCT programs could have affected the study outcomes. For example, Bolsa Familia, the Brazilian CCT, does not have health education lectures’ attendance as a condition for the participants receiving the cash transfer, even though these activities are seen as an important tool for the adoption of healthier behavioral practices [32]. On the other hand, Brazil has a large school feeding program in public schools that could complement the potential CCT effects on health and nutrition.

Income transfers alone or the use of conditional mechanisms to improve health may not be able to mitigate health inequalities in the presence of poor access to health services. Therefore investment in the supply-side of health services in the geographic locations targeted by the CCTs would improve health outcomes [33].

In addition, it should also be noticed that CCTs were mainly created for poverty reduction and development. Since many of the vulnerable groups are negatively affected by health inequities, the lack of access to financial resources could limit improvements in health status [33].

From a SHD perspective, income transfer alone is insufficient to mitigate unfair health inequalities because there is also a need to empower the most vulnerable and marginalized groups [34]. Although there is evidence of women empowerment through the participation of CCTs [35] and important advances in social inclusion [5], CCTs could inhibit social participation since the large-scale programs operate with a top-bottom approach in which governments dictate the eligible criteria and cash transfer conditions without any participation of the targeted population. Therefore, hierarchy powers in the case of CCTs could undermine the control that individuals and communities have over their lives [36].

Study limitations

Three main limitations of the present literature review need to be acknowledged. First, although the methods for searching the literature were systematic, it is not prudent to guarantee that all relevant studies on the CCTs and children’s health outcomes have been identified. There was a limited number of languages and electronic bibliographical databases adopted in the study. In addition to this, our literature review used only second-handed data, so publication bias could be an issue. Third, we have not included gray literature, which have a considerable body of literature regarding CCTs and child health and represent an important source of information.

Conclusions

CCTs seek to create life chances for children to overcome poverty and exclusion, thus reducing inequality of opportunity. We identified that CCTs created health opportunities for children, even though there was a variety of study design and methods that made it a challenge to compare study results.

The creation of health opportunities for children by the CCTs could have positively impacted health inequalities, but these results are reduced in face of poor health services and limited social participation of beneficiaries in the decisions regarding the implementation and conditions of the program.

Moreover, we noticed that there is a lack of methodological research focused in describing the mechanisms of how this equality of opportunity functions, especially in health. Our study tried to fulfill this gap by suggesting a definition for the creation of equality of opportunity in health based on the case of CCTs. In depth theoretical studies regarding this concepts are important to improve the construction of a framework to guide policy decisions in health.

References

Shibuya K. Conditional cash transfer: a magic bullet for health? Lancet. 2008;371:789–91.

Fiszbein A, Schady N, Ferreira HGF, Grosh M, Kelleher N, et al. Conditional Cash Transfers Reducing Present and Future Poverty. World Bank; 2009. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCCT/Resources/5757608-1234228266004/PRR-CCT_web_noembargo.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

Owusu-Addo E, Cross R. The impact of conditional cash transfers on child health in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:609–18.

De Brauw A, Gilligan DO, Hoddinott J, Roy S. The Impact of Bolsa Família on Schooling. World Dev. 2015;70:303–16.

De la Brière B, Rawlings LB. Examining Conditional Cash Transfer Programs: A Role for Increased Social Inclusion? The World Bank; 2006. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-papers/Safety-Nets-DP/0603.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

Roemer JE. A Pragmatic Theory of Responsibility for the Egalitarian Planner. Philos Public Aff. 1993;22:179–96.

Ham A. The impact of conditional cash transfers on educational inequality of opportunity. Lat Am Res Rev. 2014;49:153–75.

Dias PR. Inequality of opportunity in health: evidence from a UK cohort study. Health Econ. 2009;18:1057–74.

Figueroa JL. Distributional effects of Oportunidades on early child development. Soc Sci Med. 2014;113:42–9.

World Health Organization: Social determinants of health. 2017. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–104.

Con SDof H. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. rep. World Health Organization; 2008. Accessed 26 Feb 2017.

Grantham-Mcgregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:60–70.

World Health Organization. Early child development. 2017. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/themes/earlychilddevelopment/en/. Accessed 26 Feb 2017.

Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Data Syst Rev. 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008137.

Jusot F, Mage S, Menendez M: Inequality of Opportunity in health in Indonesia. Working paper. Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation; 2014.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–53.

The World Bank: World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2017. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Carvalho N, Thacker N, Gupta SS, Salomon JA. More evidence on the impact of India’s conditional cash transfer program, Janani Suraksha Yojana: quasi-experimental evaluation of the effects on childhood immunization and other reproductive and child health outcomes. PLoS One. 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109311.

Barham T, Maluccio JA. Eradicating diseases: the effect of conditional cash transfers on vaccination coverage in rural Nicaragua. J Health Econ. 2009;28:611–21.

Robertson L, Mushati P, Eaton JW, Dumba L, Mavise G, Makoni J, Schumacher C, Crea T, Monasch R, Sherr L, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Effects of unconditional and conditional cash transfers on child health and development in Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1283–92.

Huerta MC. Child health in rural Mexico: has progresa reduced children’s morbidity risks? Soc Policy Adm. 2006;40:652–77.

Barham T. A healthier start: the effect of conditional cash transfers on neonatal and infant mortality in rural Mexico. J Dev Econ. 2011;94:74–85.

Guanais FC. The combined effects of the expansion of primary health care and conditional cash transfers on infant mortality in Brazil, 1998–2010. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2000–6.

Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CA, Paes-Sousa R, Barreto ML. Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet. 2013;382:57–64.

Shei A. Brazil's conditional cash transfer program associated with declines in infant mortality rates. Health Aff. 2013;32:1274–81.

Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375:2009–23.

Paes-Sousa R, Santos LMP, Miazaki ÉS. Effects of a conditional cash transfer programme on child nutrition in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:496–503.

Saldiva SRDM, Ferraz LF, Saldiva PHN. Anthropometric assessment and food intake of children younger than 5 years of age from a city in the semi-arid area of the Northeastern region of Brazil partially covered by the bolsa família program. Rev Nutr. 2010;23:221-29.

Dos Santos FPC, De Vitta FCF, De Conti MHS, Marta SN, Gatti MAN, Simeão SFAP, De Vitta A. Nutritional condition of children who benefit from the “Bolsa Família” programme in a city of northwestern São Paulo state, Brazil. J Hum Growth Dev. 2015;25:313–8.

Behrman JR, Parker SW. Is health of the aging improved by conditional cash transfer programs? Evidence from Mexico. Demography. 2013;50(4):1363–86.

Gaarder MM, Glassman A, Todd JE. Conditional cash transfers and health: unpacking the causal chain. J Dev Eff. 2010;2:6–50.

Forde I, Bell R, Marmot MG. Using conditionality as a solution to the problem of low uptake of essential services among disadvantaged communities: a social determinants view. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1365–9.

De Brauw A, Gilligan DO, Hoddinott J, Roy S. The impact of Bolsa Família on Women’s decision-making power. World Dev. 2014;59:487–504.

Barber SL, Gertler PJ. The impact of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme, Oportunidades, on birthweight. Tropical Med Int Health. 2008;13:1405–14.

Barber SL, Gertler PJ. Empowering women: how Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme raised prenatal care quality and birth weight. J Dev Eff. 2010;2:51–73.

García-Parra E, Ochoa-Díaz-López H, García-Miranda R, Moreno- Altamirano L, Morales H, Estrada-Lugo EIJ, Hérnández RS. Estado nutricio de dos generaciones de hermanos(as) < de 5 años de edad beneficiarios(as) de Oportunidades, en comunidades rurales marginadas de Chiapas, México. Nutr Hosp. 2015;31:2685–91.

Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Neufeld LM. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: an analysis of Mexico's Oportunidades. Lancet. 2008;371:828–37.

Powell-Jackson T, Mazumdar S, Mills A. Financial incentives in health: New evidence from India's Janani Suraksha Yojana. J Health Econ. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.07.001.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RCBS contributed to the study conceptualization and design; performed the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; assured the approval of all authors; and submitted the paper on behalf of the authors. LBAM contributed to the study conceptualization and design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript revision. JJSN contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Detailed search strategies. (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cruz, R.C.d., Moura, L.B.A. & Soares Neto, J.J. Conditional cash transfers and the creation of equal opportunities of health for children in low and middle-income countries: a literature review. Int J Equity Health 16, 161 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0647-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0647-2