Abstract

Background & aim

No study is available that explores the association of dietary phytochemical index (DPI) with glioma. The objective of the current study was to assess this association in Iranian adults.

Methods

This hospital-based case-control study included 128 newly-diagnosed cases of glioma and 256 age- and sex-matched controls. Data collection on dietary intakes was done using a 123-item validated food frequency questionnaire. Calculation of DPI was done as (dietary energy derived from phytochemical-rich foods (kcal)/total daily energy intake (kcal)) × 100. Logistic regression models were used to examine the association between DPI and glioma.

Results

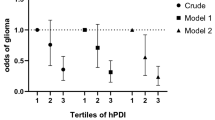

Individuals in the top tertile of DPI were more likely to be older and female. Before taking potential confounders into account, subjects in the top tertile of DPI tended to have a 40% reduced chance of glioma than those in the bottom tertile (OR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.35–1.02, P = 0.06). After controlling for age, sex, energy intake, several demographic variables and dietary intakes, the association between DPI and glioma became strengthened (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.19–0.97, P = 0.04).

Conclusion

High intakes of phytochemical-rich foods were associated with a lower risk of glioma in adults. High consumption of phytochemical-rich foods might be recommended to prevent glioma. However, further studies with a prospective design are needed to confirm our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glioma, the most prevalent brain tumor, refers to all tumors that are supposed to originate from neuroglial cells [1]. About 77% of all brain malignant tumors are attributed to glioma [2]. The estimated incidence rate of brain tumors is 3.7 per 100,000 for men and 2.6 per 100,000 for women globally [3]. A mortality rate of 2.92 per 100,000 in men and 2.46 per 100,000 in women has been reported by a national study in Iran [4]. Due to the invasive nature and difficulty in removing affected areas, glioblastoma (which accounts for 45% of all gliomas) is known as cancer with the most inferior survival rate among various cancers [5]. Given the high mortality rate of brain malignancies, prioritizing the identification of contributing factors to the incidence and development of glioma is essential [6].

Earlier studies have reported some risk factors for glioma. For instance, farming was considered a high-risk job for glioma [7] because farmers do not wash their bodies immediately or do not take off the clothes after handling pesticides. In addition, residential places close to electromagnetic fields, broadcast and cell phone antennas over the last ten years were also reported as high-risk regions for the incidence of glioma [8]. Diet is a modifiable contributing factor to the abnormal proliferation and transformation of neuroglial cells [9, 10]. Epidemiologic studies on some food groups, including fresh fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes in relation to glioma, have yielded protective associations [11,12,13]. These plant-based foods are rich in antioxidants, fiber and phytochemicals [14]. Flavonoids, phenolic acids, indoles, glucosinolates, phytoestrogens and isothiocyanates are the main phytochemicals (non-nutritive bioactive compounds) [15, 16], that were linked with cancer risk reduction [17]. In addition, the modulatory effect of phytochemicals on glioma’s degree of aggressiveness has been shown by several investigations [18]. Due to health promotional effects attributed to phytochemicals, measurement of dietary phytochemical quantity was proposed. Since the determination of diet’s phytochemical content was infeasible, the concept of the dietary phytochemical index (DPI) was suggested by McCarty. DPI is calculated via a simple method defined as the percentage of calorie intake derived from foods rich in phytochemicals [19]. This index has been proposed as an indicator of total phytochemical content of the diet and an index of better diet quality [20, 21]. Earlier studies have linked DPI to several chronic diseases. For instance, diets with a high DPI were inversely associated with obesity, oxidative stress, hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, hypertension and breast cancer [20, 22,23,24,25]. With respect to diet-glioma relations, although several dietary determinants have been reported, limited information are available about the association of DPI with this condition. Considering the inverse association between phytochemical-rich foods with glioma in earlier studies [26,27,28], we hypothesized that DPI might be associated with brain tumors. Therefore, we aimed to assess DPI in relation to the risk of glioma in the framework of a case-control study in Iranian adults.

Methods

Study design and subjects

Detailed information about study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria of this hospital-based case-control study have been reported previously [29]. Briefly, among 235 newly diagnosed pathologically confirmed glioma patients, the following cases were not included: 25 cases due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, 30 cases due to having severe form of glioma and disability, 22 cases due to their avoidance to cooperate and 30 cases due to defective medical information. Finally, 128 patients, including 75 men and 53 women aged between 20 and 75, were included. Among outpatients or admitted patients to the orthopedic and reconstructive surgery wards, 256 subjects, including 150 men and 106 women aged between 20 and 75, met our inclusion criteria. Included subjects were younger, leaner and also had higher education compared with excluded volunteers. Finally, we enrolled 128 cases and 256 matched (in the term of age and sex) controls between November 2009 and September 2011 in Tehran, Iran. The hospitals affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences were chosen as sampling sites using the convenience sampling method. Patients referring to the Neurosurgery department of the hospital, who had met our inclusion criteria, were regarded as cases. Individuals with pathologically confirmed glioma in the first month following detection (ICD-O-2, morphology codes 9380e9481), who were aged within the range of 20–75 years, were recruited. Controls were chosen from apparently healthy individuals (aged within the range of 20–75) who had been referred to other wards (orthopedic or surgery wards) of the same hospital. All cases and controls completed an informed consent form before data collection initiation. The main project on glioma was first ethically approved by the Iran National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute in 2009, before the study (Ethical code: 39414). Then, based on the main dataset, other projects were defined, each with a different exposure. Mostly, each of these projects that were later written based on that dataset has its own approvals. For the current study, the Medical Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethically approved the study (2020/06/22, Ethical code, IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1399.162).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualified cases for taking part in our project were those who met the following inclusion criteria (1) individuals with pathologically confirmed glioma with a maximum one-month interval after diagnosis of glioma, (2) aged between 20 and 75 years old. Controls were healthy subjects that had the same age and sex as cases.

The following items were regarded as exclusion criteria: (1) being pregnant or lactating, (2) having a history of some disorders including cancer (only in control groups), neurological, gastrointestinal, hepatic, endocrine, immune, kidney and cardiovascular diseases in medical records, (3) being on special diets, which might result in changes in routine dietary intakes, (4) having any history of chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and (5) use of nitrosamine-enhancing drugs (Fig. 1).

Dietary intake assessment

In this study, trained interviewers administered a Block-format-validated 123-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to evaluate dietary intakes of subjects over the past year [30]. Each participant reported his/her average intakes of different food items (per day, week or month) in a face-to-face interview. Considering the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s food composition database (modified for Iranian foods) [31], daily nutrients and energy intakes were estimated using Nutritionist IV software (First Databank, Hearst Corp., SanBruno, CA, USA). A validation study [17] revealed reasonable estimates of long-term dietary intakes for this questionnaire because good correlations were seen between dietary intakes obtained from this questionnaire and those from the average of 24-h dietary recalls (two recalls in each month of a year) as the gold standard. For example, energy-adjusted correlation coefficients for vitamin C, vitamin E and b-carotene were estimated as 0.65, 0.65, and 0.68, respectively [16, 18].

Calculation of dietary phytochemical index

We estimated DPI using McCarty equation [10]:

The phytochemical-rich foods we considered in the current study were as follows: Whole grains (Sangak and Barbari bread, which are traditional Iranian breads); fruits (red, yellow and orange fruits); vegetables (dark green vegetables, red, orange vegetables, starchy vegetables and other vegetables); soy products (soybean); nuts (peanut, almond, walnut, pistachio and hazelnut); legumes (lentil, beans, chickpea); olives; olive oil; natural fruit and vegetable juices (carrot juice, orange juice, Limon juice). Potato, as a food item in the vegetable group, was not considered in DPI calculation due to its low content of phytochemicals.

Assessment of glioma

Detection of glioma was performed based on the pathological test ICD-O-2 and morphology codes 9380–948 [29]. Glioma patients who had passed a maximum of one month of the disease confirmation were included in our study.

Assessment of other variables

A pretested questionnaire including several variables of sociodemographic status such as age (years), gender (male/female), the status of marriage (married/unmarried), residence place (urban/rural), occupation (farmer/non-farmer), education (university graduated/non-university graduated) and family history of glioma and any other cancer (yes/no), a history of trauma, hypertension and allergy (yes/no), dealing with chemicals during the past ten years (yes/no), methods of cooking (barbecue/microwave/canned foods/fried foods), drug use (yes/no), use of hair dye (yes/no), cell phone use duration (years), exposure to the radiographic x-ray (yes/no); was applied to collect general information of participants. Measurement of participants’ physical activity was done using a short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Data from IPAQ were stated as Metabolic Equivalent per week (METs/week). Anthropometric measurements were quantified via standard methods. Considering weight and height, body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each participant.

Statistical analysis

All subjects were classified based on the DPI score into tertile ranges. The distribution of study participants in terms of general characteristics across tertiles of DPI was assessed using the Chi-square test. Differences in continuous variables across DPI tertiles were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by pairwise post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of DPI with glioma. Age (continuous), sex (male/female), energy intake (kcal/day), physical activity (continues), family history of cancers (yes/no), family history of glioma (yes/no), marital status (yes/no), education (university graduated/ non-university graduated), high-risk occupation (farmer/non-farmer), high-risk residential area (yes/no), duration of cell phone use (continues), supplement use (yes/no), history of exposure to the radiographic X-ray (yes/no), history of head trauma (yes/no), history of allergy (yes/no), history of hypertension (yes/no), smoking status (smoker/non-smoker), exposure to chemicals (yes/no), drug use (yes/no), personal hair dye (yes/no), frequent fried food intake (yes/no), frequent use of barbecue (yes/no), canned foods and microwave (yes/no), dietary intakes of red and processed meat, fish, tea, coffee, sugar-sweetened beverages, egg, total fat, dietary fiber, cholesterol, calcium, SFA, folate, and selenium were adjusted in the multivariable-adjusted model. The selection of these confounders was made based on previous publications [11, 32,33,34]. The model goodness-of-fit was examined using Hosmer–Lemeshow test. By considering tertiles of DPI as ordinal variables, the overall trend of ORs across increasing tertiles of DPI was examined. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., version 19). The significance of P-values was considered at < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the percentage of subjects consuming adequate nutrient intakes from food and supplements. All participants in both case and control groups met RDA for protein and carbohydrate (100%). However, inadequate intake was likely for 10 of 12 evaluated macronutrients, vitamins and minerals. Although most participants were likely to have adequate intakes of dietary fiber, SFA, vitamin B6, vitamin C, and potassium, less than 30% of participants did not meet the DRIs for these nutrients. In addition, the majority of participants did not meet adequate intakes of vitamin E. Less than half of female cases and controls had adequate intakes of calcium, while more than half of male cases and controls had adequate intakes of this nutrient. More than 90 % of female cases and controls did not meet the DRI for folate. The corresponding percentage for male controls was 67.8% and for male cases was 69.3%.

Cases and controls were not significantly different in terms of mean age, BMI and physical activity. The comparison of general characteristics of study participants across DPI tertiles revealed that individuals in the highest tertile were more likely to be physically active, use hair dye and drugs than those in the lowest tertile. A higher percentage of subjects in the highest category of DPI were married than those in the lowest category. Higher DPI was associated with older age and less frequent fried food intake. A lower percentage of individuals in the highest category of DPI were males. Subjects in the highest category of DPI had shorter cell phone use duration compared with those in the lowest category. No other significant differences were seen in terms of other general characteristics across tertiles of DPI (Table 2).

Table 3 presents the dietary intakes of study participants across tertiles of DPI. Individuals in the top tertile of DPI had higher intakes of vegetables, fruits, legumes and whole grains, and they had lower intakes of dietary fiber, red and processed meats, cholesterol, folate, selenium, refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverage compared with those in the bottom tertile.

Crude and multivariable-adjusted ORs for glioma across tertiles of the DPI are presented in Table 4. Before taking potential confounders into account, subjects in the top tertile of DPI tended to have a 40% reduced chance of having glioma than those in the bottom tertile (OR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.35–1.02, P = 0.06). After controlling for age, sex, energy intake, several demographic variables and dietary intakes, the association between DPI and glioma became strengthened (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.19–0.97, P = 0.04). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test suggested an excellent calibration for the multivariable regression model (Chi-square = 11.06; degrees of freedom = 8; P = 0.20).

Discussion

Our findings from this hospital-based case-control study revealed an inverse association between DPI and the odds of glioma after adjusting for a wide range of potential confounders. Although several studies have suggested fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes as prophylactic agents with respect to the diet-glioma link [10, 35,36,37], to the best of our knowledge, this work is the first investigation that assessed the association between DPI and glioma.

Because nearly 90 % of glioma patients die within three years after detection, it stands among the most lethal malignancies in the world [38]. Therefore, finding preventive measures is of high priority. Dietary factors play a pivotal role in the incidence and development of glioma [39]. Dietary indices, that reflect diet quality, have frequently been used to investigate diet-disease relations. It seems that DPI can also be considered as an indicator of better diet quality [40].

In the current study, subjects in the top tertile of DPI had 57% lower odds of glioma than those in the bottom tertile. Food groups that are considered phytochemical-rich sources have previously been investigated regarding glioma risk [39, 41, 42]. For instance, dietary intake of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts have been assessed in relation to glioma [39, 41, 42]. In line with our findings, a case-control study on the link between the DASH-style eating pattern (which is rich in fruits, vegetables, plant proteins from nuts and legumes) and risk of glioma reported that individuals with the greatest adherence to the DASH diet were 72% less likely to have glioma compared with those with the lowest adherence [41]. Also, the Mediterranean diet, which is characterized by high intakes of vegetables, legumes, fruits, whole grains and olive oil, has been assessed in relation to the risk of cancer in a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies; such that the highest adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a lower risk of several cancers. However, no significant association was found for esophageal/ ovarian/ endometrial and bladder cancer [43]. Findings from a recent meta-analysis suggested an inverse association between vegetable intake and the risk of glioma [42]. In that analysis, a protective association was also reported between fruit consumption and glioma in Asian population, but not among white population [42]. There was an inverse association between whole-grain intake and total cancer [44]. Finally, an inverse association was found between legume consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in a meta-analysis on prospective cohort studies [45]. Overall, it seems that all foods with a high content of phytochemicals might help to prevent cancer incidence, including glioma.

Various mechanisms have been hypothesized linking phytochemical-rich foods with glioma. Anticancer property has been attributed to the main phytochemicals in these sources. It is well-known that oxidative stress is a process by which produced reactive oxygen species take part in glioma pathogenesis and antioxidant intake can prevent the development of glioma [39]. Phytochemicals as the main ingredients of the diet with antioxidant property [46] may exhibit favorable effects in this regard. In addition, phytochemicals take part in health and physiology function through anti-inflammatory potential and as an anti-proliferative agent for initiated and transformed cells modulate critical cellular signaling pathways [47, 48].

Several strengths of the present study worth noting. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the association between DPI and glioma risk. Adjustment for a wide range of potential confounders indicated an independent link between DPI and odds of glioma. In addition, cases were selected from newly-diagnosed glioma patients due to the possibility of altering their dietary habits after glioma detection. Finally, previous investigations proved the effect of energy intake on all foods and nutrients; therefore, energy-adjusted DPI was used to remove energy from other foods and nutrients. This can help reducing misclassification of study participants in terms of DRI. Limitations of our study include the following: (a) lack of containing all the dietary items of phytochemical-rich foods like spices in the DPI calculation, (b) the inherent limitations in the calculation of DPI; for instance, non-caloric phytochemical-rich foods like green and black tea were not included in the calculation. In addition, lack of differentiation between consumed phytochemicals’ type in DPI score, to elaborate, a diet with more legumes and nuts may have the same DPI score as a diet with more fruits and vegetables; therefore, the various quality of dietary phytochemicals among people with the same DPI score affects the risk of glioma differently, (c) the U.S. Department of Agriculture FCT was applied to calculate energy and nutrient intakes due to incompetence Iranian FCT, (d) the nature of case-control design with its inherent possibility of selection and recall bias would not allow us to confer causality, (e) using FFQ for dietary assessment results in misclassification which is unavoidable in epidemiologic studies, (f) lack of the use of molecular parameters along with tumors’ morphology to identify the tumors, and (g) as eating habits of Iranians are different from other countries in the world, the generalizability of our findings must be done cautiously. Although the results cannot be extrapolated to populations of other countries, it must be kept in mind that phytochemicals exist in various dietary sources. Based on the current study’s findings, taking these dietary components from any food source might help prevent glioma even in other populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case-control study’s findings indicate that a diet with a high amount of phytochemical-rich foods was associated with a lower odds of glioma in Iranian adults. Although our findings support the current recommendations of consumption of phytochemical-rich foods in the daily diet, it seems that adherence to popular diets that include high amounts of fruit and vegetables, including the Mediterranean diet or the vegetarian diets with low refined grains, potato products, hard liquors, added sugars and oils might help preventing glioma. Of note, the DPI of most current diets, especially in developed countries, would be unlikely to be as high as 20, which means that there would be quite ample room for improvement. Considering that such modification would result in increased intakes of potassium, fiber, vitamins, trace minerals and plant proteins and increase dietary phytochemical intake, the contribution of such diets to human health would be enormous.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DPI:

-

Dietary phytochemical index

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- IPAQ:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ANOVA:

-

One-way analysis of variance

References

World Health O. Mental health in primary care: illusion or inclusion? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Simon KC, Schmidt H, Loud S, Ascherio A. Risk factors for multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica and transverse myelitis. Mult Scler. 2015;21(6):703–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514551780.

Stein DJ, Scott KM, de Jonge P, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: from surveys to nosology and back. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19:127–36.

Noorbala AA, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Yasamy MT, Mohammad K. Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(1):70–3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.184.1.70.

Butt MS, Sultan MT. Coffee and its consumption: benefits and risks. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2011;51(4):363–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408390903586412.

Grosso G, Micek A, Castellano S, Pajak A, Galvano F. Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(1):223–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201500620.

Ruder AM, Carreón T, Butler MA, Calvert GM, Davis-King KE, Waters MA, et al. Exposure to farm crops, livestock, and farm tasks and risk of glioma: the upper Midwest health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(12):1479–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp075.

Morgan LL, Miller AB, Sasco A, Davis DL. Mobile phone radiation causes brain tumors and should be classified as a probable human carcinogen (2A). Int J Oncol. 2015;46(5):1865–71. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2015.2908.

Wang L, Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Coffee and caffeine consumption and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Australian & New Zealand J Psychiatry. 2016;50(3):228–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415603131.

Lucas M, Mirzaei F, Pan A, Okereke OI, Willett WC, O'Reilly EJ, et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1571–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.393.

Iranpour S, Sabour S. Inverse association between caffeine intake and depressive symptoms in US adults: data from National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2005-2006. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:732–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.004.

Omagari K, Sakaki M, Tsujimoto Y, Shiogama Y, Iwanaga A, Ishimoto M, et al. Coffee consumption is inversely associated with depressive status in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2014;55(2):135–42. https://doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.14-30.

Kim J, Kim J. Green tea, coffee, and caffeine consumption are inversely associated with self-report lifetime depression in the Korean population. Nutrients. 2018;10:1201–11.

Navarro AM, Abasheva D, Martínez-González MÁ, Ruiz-Estigarribia L, Martín-Calvo N, Sánchez-Villegas A, et al. Coffee consumption and the risk of depression in a middle-aged cohort: the sun project. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091333.

Kwok MK, Leung GM, Schooling CM. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, depression and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36500. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36500.

Eaton WW, McLeod J. Consumption of coffee or tea and symptoms of anxiety. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(1):66–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.74.1.66.

Yu ZM, Parker L, TJB D. Associations of coffee, diet drinks, and non-nutritive sweetener use with depression among populations in eastern Canada. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6255. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06529-w.

Jin MJ, Yoon CH, Ko HJ, Kim HM, Kim AS, Moon HN, et al. The relationship of caffeine intake with depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep in Korean adolescents. Korean J Fam Med. 2016;37(2):111–6. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2016.37.2.111.

Wang ET, de Koning L, Kanaya AM. Higher protein intake is associated with diabetes risk in south Asian Indians: the metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis in south Asians living in America (MASALA) study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29(2):130–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2010.10719826.

Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Rajaie S, Askari G, Feinle-Bisset C, Adibi P. A dish-based semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire for assessment of dietary intakes in epidemiologic studies in Iran: design and development. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:29.

Ghafarpour M, Houshiar-Rad A, Kianfar H, Ghaffarpour M. The manual for household measures, cooking yields factors and edible portion of food; 1999.

Haghighatdoost F, Azadbakht L, Keshteli AH, Feinle-Bisset C, Daghaghzadeh H, Afshar H, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and common psychological disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(1):201–9. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.105445.

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-14.

Montazeri A, Harirchi AM, Shariati M, Garmaroudi G, Ebadi M, Fateh A. The 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-66.

Schmitz N, Kruse J, Heckrath C, Alberti L, Tress W. Diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the general health questionnaire (GHQ) and the symptom check list (SCL-90-R) as screening instruments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(7):360–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050156.

Department of Health. The general practice physical activity questionnaire. London: Department of Health; 2009.

Aminianfar A, Saneei P, Nouri M, Shafiei R, Hassanzadeh-Keshteli A, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. Validity of self-reported height, weight, body mass index and waist circumference in Iranian adults. Int J Prevent Med. 2019. [In press].

Ruusunen A, Lehto SM, Tolmunen T, Mursu J, Kaplan GA, Voutilainen S. Coffee, tea and caffeine intake and the risk of severe depression in middle-aged Finnish men: the Kuopio Ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(8):1215–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010000509.

Kimura Y, Suga H, Kobayashi S, Sasaki S. Intake of coffee associated with decreased depressive symptoms among elderly Japanese women: a multi-center cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol. 2019;30(8):338–44.

Pham NM, Nanri A, Kurotani K, Kuwahara K, Kume A, Sato M, et al. Green tea and coffee consumption is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(3):625–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013000360.

Park RJ, Moon JD. Coffee and depression in Korea: the fifth Korean National Health and nutrition examination survey. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(4):501–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.247.

Botella P, Parra A. Coffee increases state anxiety in males but not in females. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2003;18(2):141–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.444.

Mino Y, Yasuda N, Fujimura T, Ohara H. Caffeine consumption and anxiety and depressive symptomatology among medical students. Arukoru kenkyu to yakubutsu izon= Japanese journal of alcohol studies & drug dependence. 1990;25:486.

Herhaus B, Kersting A, Brähler E, Petrowski K. Depression, anxiety and health status across different BMI classes: a representative study in Germany. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.020.

Godos J, Pluchinotta FR, Marventano S, Buscemi S, Li Volti G, Galvano F, et al. Coffee components and cardiovascular risk: beneficial and detrimental effects. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014;65(8):925–36. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2014.940287.

Hritcu L, Ionita R, Postu PA, Gupta GK, Turkez H, Lima TC, et al. Antidepressant flavonoids and their relationship with oxidative stress. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:5762172.

Shi X, Zhou N, Cheng J, Shi X, Huang H, Zhou M, et al. Chlorogenic acid protects PC12 cells against corticosterone-induced neurotoxicity related to inhibition of autophagy and apoptosis. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;20(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-019-0336-4.

Cokkinides V, Albano J, Samuels A, Ward M, Thum J. American cancer society: Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2005.

Chen H, Ward MH, Tucker KL, Graubard BI, McComb RD, Potischman NA, et al. Diet and risk of adult glioma in eastern Nebraska, United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(7):647–55. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019527225197.

McCarty MF. Proposal for a dietary “phytochemical index”. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63(5):813–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2002.11.004.

Benisi-Kohansal S, Shayanfar M, Mohammad-Shirazi M, Tabibi H, Sharifi G, Saneei P, et al. Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension-style diet in relation to glioma: a case–control study. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(6):1108–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515005504.

Li Y. Association between fruit and vegetable intake and risk for glioma: a meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2014;30(11-12):1272–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2014.03.027.

Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Galbete C, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101063.

Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes LT, Boffetta P, Greenwood DC, et al. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. bmj. 2016;353:i2716.

Zhu B, Sun Y, Qi L, Zhong R, Miao X. Dietary legume consumption reduces risk of colorectal cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):8797. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08797.

Moline J, Bukharovich I, Wolff M, Phillips R. Dietary flavonoids and hypertension: is there a link? Med Hypotheses. 2000;55(4):306–9. https://doi.org/10.1054/mehy.2000.1057.

Shu L, Cheung K-L, Khor TO, Chen C, Kong A-N. Phytochemicals: cancer chemoprevention and suppression of tumor onset and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(3):483–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-010-9239-y.

Tan AC, Konczak I, Sze DM-Y, Ramzan I. Molecular pathways for cancer chemoprevention by dietary phytochemicals. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(4):495–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2011.538953.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

With thanks to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, financial support of the study was provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors took part in the planning of the study. The statistical analyses were performed by SMM and AE. MS, MMS and GS all contributed to the data collection.AE interpreted the glioma patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. SR drafted the manuscript, and it was corrected and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The main project on glioma was first ethically approved by the Iran National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute in 2009, before the study (Ethical code: 39414). Then, based on the main dataset, other projects were defined, each with a different exposure. Mostly, each of these projects that were later written based on that dataset, has its own approvals. For the current study, the Medical Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethically approved the study (2020/06/22, Ethical code: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1399.162). All participants gave oral informed consent before entering the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rigi, S., Shayanfar, M., Mousavi, S.M. et al. Dietary phytochemical index in relation to risk of glioma: a case-control study in Iranian adults. Nutr J 20, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00689-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00689-2