Abstract

Background

Dengue and malaria are two common, mosquito-borne infections, which may lead to mortality if not managed properly. Concurrent infections of dengue and malaria are rare due to the different habitats of its vectors and activities of different carrier mosquitoes. The first case reported was in 2005. Since then, several concurrent infections have been reported between the dengue virus (DENV) and the malaria protozoans, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. Symptoms of each infection may be masked by a simultaneous second infection, resulting in late treatment and severe complications. Plasmodium knowlesi is also a common cause of malaria in Malaysia with one of the highest rates of mortality. This report is one of the earliest in literature of concomitant infection between DENV and P. knowlesi in which a delay in diagnosis had placed a patient in a life-threatening situation.

Case presentation

A 59-year old man staying near the Belum-Temengor rainforest at the Malaysia–Thailand border was admitted with fever for 6 days, with respiratory distress. His non-structural protein 1 antigen and Anti-DENV Immunoglobulin M tests were positive. He was treated for severe dengue with compensated shock. Treating the dengue had so distracted the clinicians that a blood film for the malaria parasite was not done. Despite aggressive supportive treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU), the patient had unresolved acidosis as well as multi-organ failure involving respiratory, renal, liver, and haematological systems. It was due to the presentation of shivering in the ICU, that a blood film was done on the second day that revealed the presence of P. knowlesi with a parasite count of 520,000/μL. The patient was subsequently treated with artesunate-doxycycline and made a good recovery after nine days in ICU.

Conclusions

This case contributes to the body of literature on co-infection between DENV and P. knowlesi and highlights the clinical consequences, which can be severe. Awareness should be raised among health-care workers on the possibility of dengue-malaria co-infection in this region. Further research is required to determine the real incidence and risk of co-infection in order to improve the management of acute febrile illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue and malaria are two common mosquito-borne diseases in tropical countries, which are potentially fatal. Dengue is a viral disease transmitted by the ‘urban mosquito’ Aedes aegypti. The estimated global incidence of dengue is 390 million a year with about 96 million cases manifesting clinically [1]. Malaria is a protozoan disease transmitted by the ‘jungle mosquito’ Anopheles species. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 214 million malaria infections occurred worldwide in 2015 and this has led to about 438,000 deaths [2].

Dengue fever can occur simultaneously with other virus, bacteria and protozoa infection [3,4,5]. Since the first reported case of dengue-malaria co-infection in France in 2005 [6], more cases have been reported in India [7, 8], Pakistan [9, 10], Brazil [11], East Timor [12], Bangladesh [13], Indonesia [14], Cambodia [15], Malaysia [16], and Japan [17]. Among these reported cases, only Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax were involved. This case involved a concurrent infection of dengue virus (DENV) and Plasmodium knowlesi, which had misled clinicians resulting in delayed treatment with life-threatening consequences.

Case report

The patient was a 59-year-old man from the town of Jeli in Malaysia. Jeli lies on the edge of the Belum-Temengor rainforest, one of Malaysia’s national reserves bordering Thailand. Gradual urbanization over the past few decades has made this town an outbreak area of dengue and leptospirosis.

The patient was admitted with fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and poor oral intake over the 6 days prior to admission. He was given antipyretic and amoxicillin by his general practitioner, but his condition had worsened. No blood investigation was done. On the day of presentation, he had difficulty in breathing and was referred to hospital.

At the emergency department, the patient was conscious but lethargic. He was mildly dehydrated, blood pressure (BP) was 102/78 mmHg and heart rate was 104 bpm. Capillary refill time was less than 2 s with a high, spiking temperature of 40 °C. He was mildly jaundiced and abdomen was soft with no organomegaly. There were no signs of haemorrhagic manifestation. Respiratory rate was 35 breaths/min and oxygen saturation (SPO2) was 93% on ambient air. Lungs were clear and breath sounds were equal bilaterally. He had type I respiratory failure, with arterial blood gas (ABG) pH of 7.36, PaCO2 at 25.6 mm Hg, PaO2 at 77.4 mm Hg, bicarbonate at 21.2 mmol/L, and lactate at 1.8 mmol/L on face mask oxygen of 5 L/min. Non-invasive ventilatory (NIV) support was required to improve oxygenation. Bedside abdominal ultrasonography performed showed no hepatosplenomegaly with a normal biliary tract. Inferior vena cava (IVC) was collapsed at 0.88 cm, with a collapsibility index of more than 50%. Fluid challenge with normal saline was initiated and titrated up to 10 mL/kg/h.

Investigations done in the emergency department revealed a platelet count of 33 × 109/L and a haematocrit (HCT) level of 39.4%. A rapid test using immunochromatic technique (ICT) was positive for dengue non-structural protein1 (NS1) antigen; similarly, the serologic Anti-DENV Immunoglobulin M (IgM) testing. International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.23 and aPTT was 44.3 s. Other laboratory investigation results included: haemoglobin (14.3 g/dL), red blood cell (RBC) count (4.55 × 1012/L) and white blood cell (WBC) count (6.91 × 109/L). Hyponatraemia (131 mmol/L) was present and liver function test was deranged with a total bilirubin of 46 mmol/L, alanine transferase of 77 mmol/L and alkaline phosphatase of 151 mmol/L (Table 1). A blood film for malaria parasites was not carried out.

The patient was diagnosed as a severe dengue case and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer observation. Bedside echocardiography revealed a normal cardiac function and IVC had picked up to 1.9 cm with the collapsibility index reduced to less than 50%, which corresponded to an improved volume status. However, the serum lactate level was still increasing, acidosis worsening and urine output decreasing. Further fluid challenge was administered carefully up to 50 mL/kg over 8 h with regular IVC assessment. Intravenous ceftriaxone, 2 g daily, was initiated by the physician to cover the possibility of concomitant leptospirosis because the patient was from an outbreak area.

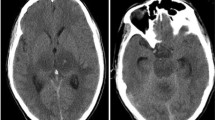

On the following day, the patient’s oxygenation deteriorated and NIV support had to be increased gradually. Under an FiO2 of 60%, ABG showed: pH 7.247, pCO2 30.4 mmHg, pO2 100 mmHg, HCO3 16.1 mmol/L and lactate 3.5 mmol/L. A chest radiograph repeated the following day showed the presence of perihilar haziness and increased pulmonary vascular markings (Fig. 1b). The patient’s platelet counts dropped further to 17 × 109/L but there was no sign of spontaneous bleeding. He also went through a few hypotensive episodes where the BP dropped to 85/50 mmHg and mean arterial pressure down to 60 mmHg. Vasopressor had to be initiated to maintain a mean arterial pressure of above 65 mmHg. Meanwhile, he suffered acute kidney injury with a urine output of 5–10 mL/h, requiring haemodialysis. Although it was the seventh day of illness (second day from admission), the patient had a spiking temperature of 38.7 °C. The fever was preceded by severe shivering which lasted for nearly an hour. This shivering led clinicians to perform a blood film for malaria parasite (BFMP). The result showed the presence of the malaria parasite resembling Plasmodium knowlesi with parasitaemia of 520,000/µL of blood. Intravenous artesunate 2.4 mg/kg daily and doxycycline 100 mg twice a day were started. Subsequently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test confirmed the parasite to be P. knowlesi. Soon after starting anti-malarial treatment, the malaria parasite count dropped to 460,000/μL after 24 h and 320/μL after 48 h, respectively. The patient’s platelet count started to improve as well (Table 1).

a Portable chest radiograph (AP view) looks normal on presentation to the emergency department (day 1); b chest radiograph repeated the following day showed the presence of perihilar haziness and increased pulmonary vascular markings (day 2); c chest radiograph showed increased air-space opacity in both lungs and parapneumonic effusion (day 6). AP anteroposterior

On the sixth day from admission, the patient’s respiratory symptoms worsened again with coarse crackles heard over both lungs on auscultation. He required NIV support to maintain an SPO2 of more than 92%. From ABG, PaO2 was 80 mmHg with FiO2 of 60%. Chest radiography showed increased air-space opacity in both lungs and parapneumonic effusion (Fig. 1c). His WBC count raised to 17.4 × 109/L with predominant neutrophilia, and C-reactive protein was more than 200 mg/L. He was then treated for hospital-acquired pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Intravenous meropenam was initiated.

With close monitoring and vigilant treatment, the patient’s condition improved. His oxygenation, renal function, liver function, and platelet count returned to normal. He was successfully weaned off NIV support on the eighth day from admission. Blood and urine cultures all yielded negative results. Serology for leptospirosis, syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV screenings were negative. Parasites were cleared from his blood on the eighth day after starting artesunate and doxycycline. He was finally able to be transferred to the general ward, and was discharged on the 15th day of hospitalization (refer Fig. 2 for event timeline). On subsequent follow-up the following month, he was discharged from the medical clinic without serious complications.

Timeline of key events. Timeline in the diagnosis, treatment and progress of the patient with concomitant dengue and Plasmodium knowlesi malaria (upper part). Progress of parasite count and usage of antibiotics (lower part). ABG arterial blood gas, CR chest radiography FBC full blood count, ICU intensive care unit, NIV non-invasive ventilation, SPO 2 oxygen saturation

Discussion

The first case of dengue-malaria dual infection was reported in France in 2005 [6] in which P. falciparum-DENV co-infection was detected, followed by a few more case reports. One year later in 2006, cases on P. vivax-DENV dual infection were reported [18, 19]. Although concurrent infection is uncommon, it has subsequently been mentioned with increasing frequency in literature. There were isolated case reports in India [7, 20,21,22,23,24], East Timor [12], Japan [17], Bangladesh [13], Indonesia [14], Malaysia [16], and Cambodia [15]. Following that, a series of cases were reported in French Guiana [25, 26], Brazil [11, 27], India [28,29,30], Bangladesh [31], Pakistan [10], Peru [32], and Kenya [33].

Studies were conducted regionally and it was noticed that the incidence of dual malaria-dengue co-infection among patients presented with acute febrile illness was actually higher than expected, ranging from 1 to 33% of the acute febrile illness state in different countries [8,9,10, 26, 33]. This increase may be explained by the overlap of vectors in endemic areas and increased prevalence of dengue fever [9, 26].

Thailand has been one of the dengue and malaria outbreak regions in Southeast Asia [2, 34]. It is an important country in malaria research because there have been reports on the artemisinin-resistant strain of falciparum malaria at the Thai–Cambodian border and the Greater Mekong Sub-region (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Viet Nam) [2, 35, 36]. Surprisingly, in a study conducted in Thailand in 2006 by Singhsilarak et al. involving 194 patients with malaria, no co-infection with dengue was found [37]. To date, there has been only one case reported in Thailand on dual dengue-malaria infection involving P. falciparum-DENV [38]. With this current incidence occurring near the Malaysia–Thailand border, awareness among doctors in this region is crucial with regard to the possibility of co-infection. Both diseases are endemic in Southeast Asia, especially in areas near to jungle that is undergoing urbanization. As for Malaysia, both diseases may overlap in Sarawak and Sabah [39], Pahang and Kelantan [40].

Clinical presentations of P. falciparum-DENV co-infections have been described over the past decade [6, 12, 17], as well as that of P. vivax and DENV co-infection [10, 11, 18]. This is probably one of the first few reports of concurrent P. knowlesi-DENV dual infection. There have been two cases of P. knowlesi-DENV co-infection reported before [41, 42], but this article is the first with a detailed case scenario and description of the dangers if misdiagnosed.

Plasmodium knowlesi is one of the most common causes of malaria-related deaths in Malaysia [2, 43]. It was first detected in Malaysia in 1965 but faced diagnostic difficulty because of its similar morphology with Plasmodium malariae. Unfortunately, it gives a more severe clinical manifestation compared to P. malariae. It can be associated with high parasitaemia and, like P. falciparum, it can be fatal [41, 43, 44]. In view of the diagnostic difficulty and the high mortality risk, the Malaysian Malaria Management Guidelines recommend that all blood film results with parasites resembling P. malariae should be reported as P. knowlesi/P. malariae and patients should be treated as P. knowlesi infection [45].

Knowlesi malaria is a simian malaria which is unlike other types of malaria as it can be carried by Old World monkeys [46, 47]. The eradication of this parasitic disease is expected to be difficult and not achievable in the near future. The incidence of co-infection should be taken seriously. Reported cases of concurrent infection in Southeast Asia are far too few compared to the dengue-malaria co-infection rate, from 1 to 33%: in French Guiana (1%) [26], Kenya (5.7%) [33], India (10.25%) [8], and Pakistan (23.21–33%) [9, 10] in local studies. The actual number of incidences are probably underestimated as such areas are known to be highly endemic for both malaria and dengue, especially around the forest area of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, East Timor, Papua, Sabah, and Sarawak.

Incidence of co-infection with dengue and malaria is likely to increase as today’s population is highly mobile, with increased activities brought about by good transportation systems. These two diseases share similar major symptoms such as fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Differentiating them is difficult on clinical grounds alone. One of the clinical signs that may suggest malaria rather than dengue in this context will be splenomegaly [48]. However, this patient had no splenomegaly and absence of splenomegaly does not rule out malaria. With the emergence of malaria-dengue co-infections, even with laboratory investigations, the risk of overlooking malaria is still high in dengue outbreak areas and vice versa. This is because they both share similar laboratory findings with dengue, such as thrombocytopaenia. In Malaysia, the confirmation tests for dengue (NS1 antigen and dengue IgM) are rapid and easily available. A positive confirmatory dengue test often misleads practitioners to rule out the possibilities of other diseases without actually screening against it [42, 49, 50].

The challenges for a reliable clinical diagnosis are further increased with atypical manifestations of dengue fever in recent years. These include dengue encephalitis, dengue myocarditis, dengue with ARDS and pleural effusion, dengue-induced hepatitis, and severe dengue causing kidney failure [51]. However, there are some signs for clinicians to suspect the presence of concomitant infection with dengue. Firstly, in most cases of dengue, the fever spikes by day 5 of illness. Fever may be prolonged in patients who have co-existing infections [52]. Secondly, patients with dengue are more likely to have a temperature under 39 °C [48]. Thirdly, they are more likely to be associated with leucopenia [48], haemo concentration [8] and atypical lymphocytosis [34, 35]. In this patient, the temperature was 40 °C on day 6 of illness, there was no haemoconcentration and no leucopenia. Additionally, he had anuria, worsening metabolic acidosis and hyperlactatemia, which was resistant to aggressive fluid resuscitation. These are strong indications to further investigate co-existing infections. In fact, a leptospirosis test was taken on admission with prophylactic treatment for leptospirosis. Unfortunately, BFMP was not done upon admission.

There is a scoring system based on clinical and laboratory criteria, described by Epelboin et al. [52], to predict the need for a parasitological examination in a febrile patient with atypical symptoms (Table 2). The patient scored 13/14 in this scoring upon admission and was indicated for a BFMP screening.

The most important lesson from this case report was that the delay in suspecting malaria infection caused a delay in treatment, which resulted in the deterioration of the patient’s condition. The history that the patient’s home was near the jungle should have prompted an early BFMP test but it was only when he developed uncorrected acidosis and the presence of shivering that this was done.

A timely diagnosis of malaria is of utmost importance because with early treatment the outcome is good. If left untreated, this condition can rapidly turn fatal as P. knowlesi has a 24-h replication cycle [53] (48 h for P. falciparum, P. vivax and P. ovale; 72 h for P. malariae [54]) which causes a drastic rise in parasitaemia leading to multiple organ failure. Additionally, treatment of these two illnesses differs. Most dengue cases can be treated with adequate supportive management, i.e., fluid replacement and other measures. Supportive management itself may reduce the mortality rate from more than 20% to less than 1% in severe dengue cases [55]. To treat malaria, specific anti-malarial medication has to be used or the infection may rapidly become fatal [56, 57]. In a case reported in East Timor, a girl who falsely tested negative for malaria with a rapid diagnostic kit died within 7 h of admission because of delayed treatment [12]. There were several mortalities in Malaysia where parenteral artesunate was delayed because P. knowlesi was wrongly reported as P. malariae, which has a relatively benign clinical course [57]. Awareness and a high index of suspicion of the possibility of dengue-malaria co-infection can be life-saving and any suspicion of such case must be carefully excluded.

The severe manifestation of this patient may be multifactorial. Apart from the delay in diagnosis and treatment, it can also be due to the co-infection of malaria and dengue which caused an exaggerated host immune response, as in the theory proposed by Mendonca et al. [58]. Concurrent infections have also been suggested to be more severe than isolated infection [25, 58]. However, this statement remains controversial. Halsey et al. reported no difference in severity between isolated infection and co-infection [32].

Conclusion

This article aims to contribute to the body of knowledge on the presentation, progress and management of P. knowlesi-DENV co-infection. This may aid similar encounters in future, especially in Southeast Asia where P. knowlesi abounds. The medical fraternity should be alert regarding the possibility of co-existing infection which may mimic the atypical presentations of dengue fever. Dengue mortality in Malaysia has been increasing [59], any emergence of undiagnosed concomitant malaria may worsen this situation. A high index of suspicion is of utmost importance to prevent deadly complications arising from delayed treatment. Further research is required to determine the real incidence in order to guide the management of acute febrile illness.

Abbreviations

- ABG:

-

arterial blood gas

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BFMP:

-

blood film for malaria parasite

- BP:

-

blood pressure

- bpm:

-

beats per minute

- DENV:

-

dengue virus

- FiO2 :

-

fraction of inspired oxygen

- HCO3 :

-

bicarbonate level

- HCT:

-

haematocrit

- ICT:

-

immunochromatic technique

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- Ig M:

-

immunoglobulin M

- IVC:

-

inferior vena cava

- NIV:

-

non-invasive ventilation

- NS1:

-

non-structural protein 1

- PaO2 :

-

partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- PaCO2 :

-

partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- RBC:

-

red blood cells

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- SPO2 :

-

oxygen saturation

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7.

WHO. World malaria report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015:280.

Sudjana P, Jusuf H. Concurrent dengue hemorrhagic fever and typhoid fever infection in adult: case report. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:370–2.

Sharma N, Mahi S, Bhalla A, Singh V, Varma S, Ratho RK. Dengue fever related acalculous cholecystitis in a North Indian tertiary care hospital. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:664–7.

Chang SF, Su CL, Shu PY, Yang CF, Liao TL, Cheng CH, Hu HC, Huang JH. Concurrent isolation of chikungunya virus and dengue virus from a patient with coinfection resulting from a trip to Singapore. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4586–9. doi:10.1128/jcm.01228-10.

Charrel RN, Brouqui P, Foucault C, de Lamballerie X. Concurrent dengue and malaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1153–4.

Arya SC, Mehta LK, Agarwal N, Agarwal BK, Mathai G, Moondhara A. Episodes of concurrent dengue and malaria. Dengue Bulletin. 2005;29:208–9.

Barua A, Yeolekar ME. Concurrent dengue and malaria coinfection: observations from a central Mumbai hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45:165.

Abbasi A, Butt N, Sheikh QH, Bhutto AR, Munir SM, Ahmed SM. Clinical features, diagnostic techniques and management of dual dengue and malaria infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:25–9.

Assir MZK, Masood MA, Ahmad HI. Concurrent dengue and malaria infection in Lahore, Pakistan during the 2012 dengue outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;18:41–6.

Magalhaes BML, Alexandre MAA, Siqueira AM, Melo GC, Gimaque JBL, Bastos MS, et al. Clinical profile of concurrent dengue fever and Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Brazilian Amazon: case series of 11 hospitalized patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:1119–24.

Ward DI. A case of fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria complicated by acute dengue fever in East Timor. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:182–5.

Faruque LI, Zaman RU, Alamgir AS, Gurley ES, Haque R, Rahman M, et al. Hospital-based prevalence of malaria and dengue in febrile patients in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:58–64.

Yong KP, Tan BH, Low CY. Severe falciparum malaria with dengue coinfection complicated by rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury: an unusual case with myoglobinemia, myoglobinuria but normal serum creatine kinase. BMC Infect Dis. 2012; 12.

Carvalho LH, Mueller TC, Siv S, Khim N, Kim S, Fleischmann E, et al. Acute undifferentiated febrile illness in rural Cambodia: a 3-year prospective observational study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95868.

Yong LS, Koh KC. A case of mixed infections in a patient presenting with acute febrile illness in the tropics. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2013;2013:562175.

Thaha M, Pranawa, Yogiantoro M, Tanimoto M, Tomino Y. Acute renal failure in a patient with severe malaria and dengue shock syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2008;70:427–30.

Deresinski S. Concurrent Plasmodium vivax malaria and dengue. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1802.

Ali N, Nadeem A, Anwar M, Tariq WU, Chotani RA. Dengue fever in malaria endemic areas. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:340–2.

Kaushik RM, Varma A, Kaushik R, Gaur KJ. Concurrent dengue and malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1048–50.

Chaudhry R, Pandey A, Das A, Broor S. Infection potpourri: are we watching? Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:125.

Chander J, Singla N, Singh R. Concurrent presence of dengue and Plasmodium falciparum. Trop Med Health. 2009;37:69–70.

Bhalla A, Sharma N, Sharma A, Suri V. Concurrent infection with dengue and malaria. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:330–1.

Thangaratham PS, Jeevan MK, Rajendran R, Samuel PP, Tyagi BK. Dual infection by dengue virus and Plasmodium vivax in Alappuzha District, Kerala, India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59:211–2.

Epelboin L, Hanf M, Dussart P, Ouar-Epelboin S, Djossou F, Nacher M, et al. Is dengue and malaria co-infection more severe than single infections? A retrospective matched-pair study in French Guiana. Malar J. 2012;11:142.

Carme B, Matheus S, Donutil G, Raulin O, Nacher M, Morvan J. Concurrent dengue and malaria in Cayenne Hospital, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:668–71.

Santana Vdos S, Lavezzo LC, Mondini A, Terzian AC, Bronzoni RV, Rossit AR, et al. Concurrent dengue and malaria in the Amazon region. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:508–11.

Bhagat M, Kanhere S, Phadke V, George R. Concurrent malaria and dengue fever: a need for rapid diagnostic methods. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3:446–8.

Mohapatra MK, Patra P, Agrawala R. Manifestation and outcome of concurrent malaria and dengue infection. J Vector Borne Dis. 2012;49:262–5.

Hati AK, Bhattacharjee I, Mukherjee H, Bandyopadhayay B, Bandyopadhyay D, De R, et al. Concurrent dengue and malaria in an area in Kolkata. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:315–7.

Swoboda P, Fuehrer HP, Ley B, Starzengruber P, Ley-Thriemer K, Jung M, et al. Evidence of a major reservoir of non-malarial febrile diseases in malaria-endemic regions of Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:377–82.

Halsey ES, Baldeviano GC, Edgel KA, Vilcarromero S, Sihuincha M, Lescano AG. Symptoms and immune markers in Plasmodium/dengue virus co-infection compared with mono-infection with either in Peru. PLOS Neglect Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004646.

Vu DM, Ripp K, Mutai N, Ndenga BA, Heath C, LaBeaud AD. Dengue virus and malaria co-infection in Kenyan children. Ann Global Health. 2016;82:435–6.

Gurugama P, Garg P, Perera J, Wijewickrama A, Seneviratne SL. Dengue viral infections. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:68–78.

Alker AP, Lim P, Sem R, Shah NK, Yi P, Bouth DM, et al. Pfmdr1 and in vivo resistance to artesunate-mefloquine in falciparum malaria on the Cambodian–Thai border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:641–7.

Phyo AP, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S, McGready R, et al. Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2012;379:1960–6.

Singhsilarak T, Phongtananant S, Jenjittikul M, Watt G, Tangpakdee N, Popak N, et al. Possible acute coinfections in Thai malaria patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:1–4.

Issaranggoon na ayuthaya S, Wangjirapan A, Oberdorfer P. An 11-year-old boy with Plasmodium falciparum malaria and dengue co-infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; 2014: bcr-2013202998.

William T, Jelip J, Menon J, Anderios F, Mohammad R, Awang Mohammad TA, et al. Changing epidemiology of malaria in Sabah, Malaysia: increasing incidence of Plasmodium knowlesi. Malar J. 2014;13:390.

Alias H, Surin J, Mahmud R, Shafie A, Mohd Zin J, Mohamad Nor M, et al. Spatial distribution of malaria in Peninsular Malaysia from 2000 to 2009. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:186.

William T, Menon J, Rajahram G, Chan L, Ma G, Donaldson S, et al. Severe Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in a tertiary care hospital, Sabah, Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1248–55.

Azira NM, Zairi NZ, Amry AR, Zeehaida M. Case series of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infection in a tertiary teaching hospital. Trop Biomed. 2012;29:398–404.

Rajahram GS, Barber BE, William T, Grigg MJ, Menon J, Yeo TW, Anstey NM. Falling Plasmodium knowlesi malaria death rate among adults despite rising incidence, Sabah, Malaysia, 2010–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:41–8.

Daneshvar C, Davis TM, Cox-Singh J, Rafa’ee MZ, Zakaria SK, Divis PC, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of human Plasmodium knowlesi infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:852–60.

Vector Borne Disease Sector. Management Guidelines of Malaria in Malaysia. Ministry of Health Malaysia. 1st edn. Malaysia, 2014:27.

van Hellemond JJ, Rutten M, Koelewijn R, Zeeman AM, Verweij JJ, Wismans PJ, et al. Human Plasmodium knowlesi infection detected by rapid diagnostic tests for malaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1478–80.

Yusof R, Lau Y, Mahmud R, Fong M, Jelip J, Ngian H, et al. High proportion of knowlesi malaria in recent malaria cases in Malaysia. Malar J. 2014;13:168.

Sung V, O’Brien DP, Matchett E, Brown GV, Torresi J. Dengue Fever in travelers returning from southeast Asia. J Travel Med. 2003;10:208–13.

Ng OT, Ooi EE, Lee CC, Lee PJ, Ng LC, Pei SW, et al. Naturally acquired human Plasmodium knowlesi infection, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:814–6.

Mohamed Z, Roshan TM. Human Plasmodium knowlesi: an emerging infection presented with severe thrombocytopenia. Int Med J. 2009;16:307–10.

Gulati S, Maheshwari A. Atypical manifestations of dengue. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1087–95.

Epelboin L, Boulle C, Ouar-Epelboin S, Hanf M, Dussart P, Djossou F, et al. Discriminating malaria from dengue fever in endemic areas: clinical and biological criteria, prognostic score and utility of the C-reactive protein: a retrospective matched-pair study in French Guiana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2420.

Cox-Singh J, Davis TM, Lee KS, Shamsul SS, Matusop A, Ratnam S, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans is widely distributed and potentially life threatening. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:165–71.

Kerlin DH, Gatton ML. Preferential invasion by Plasmodium merozoites and the self-regulation of parasite burden. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57434.

WHO factsheet. Dengue and severe dengue. Geneva: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/. Accessed 2 Sept 2016

Cox-Singh J, Hiu J, Lucas SB, Divis PC, Zulkarnaen M, Chandran P, et al. Severe malaria—a case of fatal Plasmodium knowlesi infection with post-mortem findings: a case report. Malar J. 2010;9:10.

Rajahram GS, Barber BE, William T, Menon J, Anstey NM, Yeo TW. Deaths due to Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Sabah, Malaysia: association with reporting as Plasmodium malariae and delayed parenteral artesunate. Malar J. 2012;11:284.

Mendonça VRR, Andrade BB, Souza LCL, Magalhães BML, Mourão MPG, Lacerda MVG, et al. Unravelling the patterns of host immune responses in Plasmodium vivax malaria and dengue co-infection. Malar J. 2015;14:315.

CPG Management of Dengue Infection in Adults. 3rd edn. Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2015:65.

Authors’ contributions

RHMZ performed the clinical assessments, treated the patient in the ICU, and drafted the manuscript. SEC performed the clinical assessments and treatment, searched the literature and drafted the manuscript. SS performed data collection, molecular diagnostic tests and drafted the manuscript. LKT treated the patient in the ICU, performed data collection and drafted the manuscript. LJA performed literature search, drafted and completed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Publication of this report was supported by Universiti Sains Malaysia Short Term Grant (Grant Scheme No. 304/CIPPT/6313113). We sincerely thank Mdm Lee Jong Koh for critical reading and useful comments on this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was granted from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval is not required at the authors’ institutions for the presentation of a single case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chong, S.E., Mohamad Zaini, R.H., Suraiya, S. et al. The dangers of accepting a single diagnosis: case report of concurrent Plasmodium knowlesi malaria and dengue infection. Malar J 16, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1666-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1666-y