Abstract

Background

Mass anti-malarial administration has been proposed as a key component of the malaria elimination strategy in South East Asia. The success of this approach depends on the local malaria epidemiology, nature of the anti-malarial regimen and population coverage. Community engagement is used to promote population coverage but little research has systematically analysed its impact. This systematic review examines population coverage and community engagement in programmes of mass anti-malarial drug administration.

Methods

This review builds on a previous review that identified 3049 articles describing mass anti-malarial administrations published between 1913 and 2011. Further search and application of a set of criteria conducted in the current review resulted in 51 articles that were retained for analysis. These 51 papers described the population coverage and/or community engagement in mass anti-malarial administrations. Population coverage was quantitatively assessed and a thematic analysis was conducted on the community engagement activities.

Results

The studies were conducted in 26 countries: in diverse healthcare and social contexts where various anti-malarial regimens under varied study designs were administered. Twenty-eight articles reported only population coverage; 12 described only community engagement activities; and 11 community engagement and population coverage. Average population coverage was 83% but methods of calculating coverage were frequently unclear or inconsistent. Community engagement activities included providing health education and incentives, using community structures (e.g. existing hierarchies or health infrastructure), mobilizing human resources, and collaborating with government at some level (e.g. ministries of health). Community engagement was often a process involving various activities throughout the duration of the intervention.

Conclusion

The mean population coverage was over 80% but incomplete reporting of calculation methods limits conclusions and comparisons between studies. Various community engagement activities and approaches were described, but many articles contained limited or no details. Other factors relevant to population coverage, such as the social, cultural and study context were scarcely reported. Further research is needed to understand the factors that influence population coverage and adherence in mass anti-malarial administrations and the role community engagement activities and approaches play in satisfactory participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Malaria remains a leading global health concern and although, in South East Asia, malaria-related morbidity and mortality has seen recent declines, the spread of drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites poses serious challenges to prevention and control efforts [1]. If left uncontained, the likely spread of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum from Asia to Africa would have a catastrophic impact in the region where malaria-related mortality is highest [2].

This scenario has prompted urgent efforts to eliminate falciparum malaria in South East Asia [3, 4]. One approach, targeted malaria elimination (TME), combines conventional malaria prevention and control activities (reinforcing the network of village malaria workers (VMWs) to deliver appropriate case management and distribute long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets (LLINs), with the mass administration of an artemisinin combination therapy. The mass drug administration (MDA) component of TME entails delivering a curative anti-malarial dose to all individuals within a community, irrespective of malaria infection status, to interrupt local transmission [5].

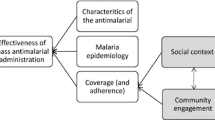

Over the past century, MDA has been used as a strategy for malaria control with varying degree of success [6]. Past mass anti-malarial administrations, which often entailed sub-therapeutic doses, have been blamed for accelerating drug resistance [5, 7]. This is less likely within TME because therapeutic doses of combination anti-malarials are administered [5–8]. Interrupting local transmission through MDA is dependent on several factors, particularly the local malaria epidemiology, the characteristics of the anti-malarial regimen, and population coverage and adherence (Fig. 1). In recent years, modelling studies have been helpful in determining the level of coverage required in specific epidemiological situations to interrupt transmission [9]. The level of coverage required to ensure the effectiveness of the MDA and how to define coverage is debatable particularly with regard to specifying numerator and denominator. For instance, many MDA studies, exclude pregnant women and young children because of concerns of toxicity. It is clear that the local social context and the community engagement activities that accompany the MDA influence coverage and adherence [9–17].

Community engagement is variously defined in the global health literature [18]. Some scholars emphasize community engagement as promoting ethical conduct of research, whereas other definitions focus on ‘working collaboratively’ with communities ‘to address issues affecting the well-being of those people’ [18, 19]. With regard to programmes of MDA, community engagement entails a range of activities—for example, employing community members and providing health education—that often focus on promoting population coverage and adherence [14, 19–22]. Although recognized as influencing coverage, community engagement is often scarcely reported and, to date, little effort have been made to analyse the impact of specific community engagement activities or approaches on MDA coverage.

With a view to designing community engagement activities for TME across the Greater Mekong sub-region, a systematic review of community engagement and population coverage within mass anti-malarial administrations was conducted [6, 23]. This article examines: (1) population coverage, (2) community engagement activities and (3) the relationship between (1) and (2) in previous mass anti-malarial administrations.

Methods

This review builds upon an earlier Cochrane review of mass anti-malarial administrations by Poirot et al. [23]. For the Cochrane review, the following databases were searched: Cochrane infectious diseases, Group Specialized Register, Cochrane central register of controlled trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Library, MEDLINE+ , EMBASE, CABS Abstracts and LILACS (Additional file 1). Search terms were: A. Anti-malarials: exp Antimalarials or exp malaria/or antimalarial* or anti-malarial* or schizonticidal* or gametocidal* or hypnozoiticidal* or drug* or treatment* or malaria* and B. Mass Administration: mass or coordinate* or administ* or distribut* or applicat* or use or therap* or treatment*.

From these searches, 3049 articles were retrieved and reviewed (Fig. 2). Of these articles, 241 were selected based on the eligibility for MDA [23]. Further review by Newby et al. [6] identified 16 sub-studies that resulted in a total of 257 full text articles. These 257 articles were subjected to the exclusion criteria (Table 1). This resulted in 201 articles published between November 30, 1931 and August 24, 2011 that were assessed for inclusion in the current review. To examine the maximum number of studies that might have documented community engagement activities and population coverage, articles excluded from previous reviews were included: articles that reported MDA for sub-groups rather than entire populations, described the delivery of inadequate treatment doses, documented the mass screen and treat approach and those that were not unique MDA studies (e.g. multiple publications documenting different components of the same study).

Two authors (BA and NJ) independently retrieved and reviewed the articles. Firstly, all the literature pertaining to malaria-related MDAs was reviewed to extract population coverage data. In this review, population coverage has been defined as the total proportion of the target population who took anti-malarials with or without directly observed treatment (DOT) during the entire course of the MDA. Secondly, the articles were sorted according to the reports of community engagement activities. Thirdly, a thematic analysis of the literature that addressed the population coverage and/or community engagement was conducted.

Of the 201 articles, 181 reported primary studies and 20 reported secondary studies, which gave additional details on the primary studies. Seventy-eight of the 181 primary studies were excluded. These were 68 non English articles, eight that reported intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) and two of which the full text were not available resulting in 103 studies. Among these 20 secondary studies, nine were excluded: two were in languages other than English, one was an unpublished working document and six described studies indirectly related to MDA (such as knowledge, attitude and practice studies, and longitudinal studies), resulting in eleven secondary studies. Of these 11 studies, two were included in the previous review of community participation by Atkinson et al. [20]. These 11 articles were reviewed for their additional details on community engagement and coverage and were used to supplement the information detailed in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Community engagement data extraction and analysis

Of the 103 primary articles, 47 were excluded after a preliminary review because they did not describe population coverage or community engagement activities (Additional file 2). Among the remaining 56 articles, six described community engagement only very briefly and were excluded [24]. One additional article was added during the update of the review [25] resulting in 51 articles retained for analysis. A thematic analysis was conducted on a total of 23 articles, which described community engagement activities. These included 12 articles that described community engagement activities only and 11 articles that described population coverage and community engagement activities.

Results

The nature of the reviewed articles

Fifty-one articles reporting the results of studies conducted in 26 countries were retained in the analysis. Population coverage without community engagement was documented in 28/51 (55%) papers (Table 2). Twelve of 51 (24%) articles described community engagement activities in detail but not population coverage (Tables 3, 5), whereas 11/51 (22%) articles described community engagement activities in detail and population coverage (Tables 4, 6). Among all articles reviewed (n = 51), median quartile of the studies were conducted before 1965 (Q1 = 1956, Q2 = 1965 and Q3 = 1984).

The studies were conducted in contexts with diverse healthcare infrastructure, health needs, population mobility and population size. For instance, the study in Lebanon involved study villages, which were deprived of healthcare centres (physicians or pharmacies were unavailable within 18 km of the village). In addition, the study population was mobile as they often leave the village in search of job and to escape the winter [26]. This had implications in terms of villagers’ willingness to follow study instructions, such as not to take other anti-malarials apart from the study drug, chloroquine.

In some cases, mass anti-malarial administration was conducted as part of research in selected villages, whereas, in others, MDA was part of a national health campaign. An example of the latter is Nicaragua where the entire population was treated. High level of community participation in a literacy campaign in previous year was a stimulus for the nationwide MDA. Prior to mass anti-malarial administration, health campaigns had been conducted for polio vaccination, sanitation and environmental hygiene, rabies control in domestic pets and vaccination against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus [27].

Population coverage

The 28 studies that documented only population coverage were published from 1931 to 1996 (Table 2). The mean reported population coverage in these 28 studies was 82% (range 40–100%), with seven (25%) studies reporting a population coverage below 79% (Table 2). The 11 articles reporting both population coverage and community engagement activities were published from 1960 to 2015 and described, on average, 84% coverage (range 40–100%). Three of the 11 (27.3%) studies reported a population coverage below 79% (Table 4). It was often unclear or not specified how the coverage was estimated. For example, in Trinidad and Tobago, 2142 people were given plasmoquine and quinine, but only 1289 people completed the full course. In this study, the coverage was not reported and the selection of the target population was not mentioned [28]. Similarly, in Sudan, the anti-malarials were reportedly taken by all members of the targeted population but no details of coverage, population size or the selection procedure were provided [29].

Community engagement activities

This section describes the type and process of community engagement activities: health education, provision of incentives, utilization of existing community structures, human resource mobilization and steps in community engagement.

Health education

Of the 23 articles (Tables 5, 6) with detailed descriptions of community engagement, 12 focused on health education employing the following media and methods: (1) newspapers, written leaflets and posters, (2) audio-visual materials, such as news-bulletins, movies and videos, and (3) meetings with key community persons, announcements in health facilities in conjunction with community members and involvement of local health workers, government health officials and village volunteers.

Two articles, reporting on studies in Nicaragua [30] and Indonesia [31] incorporated large-scale health education on malaria and MDA. Health education was conducted in various different contexts and various methods were applied. For instance, in Tanzania, articles for the general public were written in two local newspapers [32]. In Ghana, weekly health education classes were conducted among the residents and they were asked to spread the message to other villagers [33]. In India, health education sessions were conducted in different levels where community health volunteers played a major role in increasing the awareness in the community [34]. In Vanuatu, intensive health education classes were conducted after coverage dropped and in subsequent round coverage improved [14, 35]. Information dissemination was conducted through newspapers [32], pamphlets and news bulletins [36]. In two studies [37, 38] audio-visual materials were employed to explain the planned intervention [37]. In China, the health education was delivered through the primary health care system by the means of meetings, films, posters and videos [38].

Incentives

Two articles documented the use of incentives in MDA but they did not report the corresponding population coverage [37, 39]. In Venezuela, MDA participants received incentives ranging from a lottery ticket to sugar candy on completion of the entire anti-malarial course. In addition, financial incentives were provided to MDA staff for each malaria positive slide [39]. In India, financial incentives—an advance for housing construction—were given to reluctant tribal populations [37].

Community structures

Community structures consisted of existing organizations, physical infra-structure, health care providers and health service centres. The involvement of community structures was often a core component of introducing the MDA to the target communities. In India, personnel from the local health centre and additional staff from the district assisted in conducting the MDA [34]. In Kenya, the MDA was implemented in the community through the local district health office [40]. Apart from conducting community meetings and utilizing community structures, a study [25] in Thai–Myanmar border areas utilized an existing community ethics advisory board (Tak Province Community Ethics Advisory Board [T-CAB]) [41].

Human resource mobilization

Human resource mobilization varied from the simple involvement of community members or health staff to assist with the study to complete hand over of the MDA operations to government staff. For instance, in the Gambia, a translator and a fieldworker were appointed for consent process with participants whereas the staff at health centre recorded the visits of villagers at health centre [42]. In Cambodia, village malaria workers were recruited to distribute the drugs and monitor drug administration [43]. By contrast, in Nicaragua, a nationwide malaria control program recruited 70,000 people as anti-malaria volunteers who were trained to conduct the census, provide door to door education, promote community participation, distribute drugs and keep records [27]. On Aneityum Island, Vanuatu, village volunteers were selected and trained as MDA staff and were responsible for drug distribution [35].

Steps in community engagement

Community engagement was often a process and the MDAs involved participants in various ways throughout the duration of the intervention. For instance, in The Gambia, researchers first discussed the project with and sought cooperation from national and district-level members of governmental and health structures. Subsequently, meetings were conducted in the target communities with village elders and other prominent residents in the presence of the government officials [42]. With the consent of village leaders, meetings were held with community members to introduce the purpose and details of the study, which was then followed by the individual consent process. On Aneityum Island, the MDA plan was first formulated by the malaria control programme at the Department of Health. Operationally, MDA was led by the district malaria supervisor and several meetings were held with the communities to explain the MDA’s purpose and procedures, and to elicit the community’s full commitment to eliminate malaria from the island. Subsequently, 12 village volunteers were selected and trained as MDA staff and anti-malarial administration was carried out with the supervision of a registered nurse who was responsible for healthcare on the island, the district malaria supervisor and central malaria section staff [14, 35].

The relationship between community engagement and population coverage

Among the 11 studies (Tables 4, 6) that documented both community engagement activities and coverage, coverage ranged from 40 to 100% [25, 27, 34, 35, 40, 42, 44, 45]. The MDA with the highest reported population coverage (100%) was part of the North Sumatra Health Promotion Project, Indonesia and was on-going for 10 years. In this national initiative, existing village health centres and staff were responsible for the activities, such as collecting fingertip blood samples and examining spleen size. Two village volunteers also worked as recorders and guides and the primary school teacher assisted in identifying and examining pupils [44].

Another successful MDA that reached 95% of the target population was conducted in Kenya, as part of chemotherapeutic campaigns in 1953–1954 and as a joint collaboration between WHO, UNICEF and Ministry of Health. In this case, the district health offices were responsible for overall organization and supervision of the MDA and the district health inspector was charged with the daily running of the operation. Most community leaders, such as administrative chiefs, headmen, school teachers and clerks were involved [40].

On Aneityum Island, mass anti-malarial administration contributed to the elimination of malaria from the island. Here, the department of health was closely involved: the district malaria supervisor took charge of the programme and delegated responsibilities to local staff from government health facilities. Twelve community members were recruited and trained as MDA staff who carried out day-to-day activities, such as drug distribution, recording and supervision. The MDA compliance rate decreased from 90 to 79% in the 2nd and 3rd rounds; this resulted from the adverse events related to chloroquine and the number of tablets participants had to take and, in response, community meetings were held. Additional information was provided and chloroquine was removed from the scheduled anti-malarial regimen in the 5th and 9th rounds after discussion with the community [14, 35].

Amongst the articles that reported coverage and community engagement activities, the lowest coverage −40%-was recorded on the Thai–Myanmar border [25]. Initially, the mean coverage in three villages for the malaria parasite survey was 77%. After discussing the results with community leaders and the T-CAB, MDA was agreed as an intervention. Two of the three villages were inaccessible during the rainy season and so anti-malarials could not be administered there. The low coverage was explained in terms of political fragmentation, inaccessibility and high mobility [25].

Discussion

This review has identified and examined reports of mass anti-malarial administrations that described community engagement activities and/or population coverage. Conducted between December 30, 1931 and August 16, 2015, MDAs varied widely by anti-malarial regimen, study type, context, community engagement activities, and population coverage. In the following sections, the research questions are discussed with particular regard to the limitations of the reviewed articles.

Population coverage

Amongst the reviewed articles, the mean population coverage for the mass anti-malarial administrations was above 80%, the suggested minimum to interrupt malaria transmission [6]. Amongst the articles that described population coverage and community engagement activities, the mean was even higher. Furthermore, when community engagement involved government and local community structures, coverage was above 85% (range = 70–100%) [27, 34, 35, 40, 42, 44, 45] and when community engagement activities depended on the community alone, mean coverage was over 80% (range = 40–95%) [12, 25, 31, 46]. These figures suggest cause for optimism with regard to reaching the levels of coverage required to eliminate falciparum malaria from the Greater Mekong sub-region.

The reporting of how population coverage was calculated was, often absent or inadequate; little detail was offered on the denominator or numerator populations, who was excluded, for example, from anti-malarial administration, or how the total target population was calculated, with regard to including or excluding mobile groups. The absence of such detail limits direct comparisons across the studies. Ideally, future research on mass anti-malarial administration should report its fullness, the methods used to calculate population coverage.

The reviewed articles also provide few references to participants’ adherence to the anti-malarial regimen [31, 35, 36, 45, 47]. Adherence is likely to be a particular challenge when administering a multi-dose multi-day anti-malarial regimens. Although adherence can be ensured by delivering anti-malarials as DOT, this is likely to present challenges when part of large scale MDA programme. Low-prevalence settings, such as those in the Greater Mekong sub-Region, are also likely to present potential challenges for adherence if DOT is not possible. Future research should address the question of MDA adherence in areas of low clinical malaria prevalence.

Community engagement activities

The reviewed articles described community engagement activities that included the simple provision of information about the MDA to the community, the utilization of existing community structures for MDA implementation, delivery of health education, and building local human resource capacity through training. Some articles provided detailed accounts of the community engagement [14, 30], overall, there was a general lack of detail regarding the approach to community engagement and the activities conducted.

Community engagement approaches have been categorized as top-down (vertical) and bottom-up (horizontal) [20]. Many of the reviewed articles reported a combination of these approaches [27, 34, 35, 40, 42, 44, 45] and community engagement was often a process, involving multiple steps. First, the top-down approach was used to garner support of officials and gain access to the research site [48, 49]. In light of the criticisms of such an approach and the need to gain the consensus of the community, more bottom-up activities were subsequently utilized [50–52]. This is particularly the case in more recent MDAs [48, 53–55]. In many of the reviewed articles, [12, 27, 31, 34, 35, 40, 42, 44–46], the use of existing community structures, the local health system and involvement of the community in meetings, health education and training of the local staff were essential features.

Bottom-up approaches to community engagement include community-directed interventions (CDI), which entails community members taking an active role in the planning and execution of an intervention. For MDAs, such activities include carrying out the target population census, distributing drugs, mobilizing other community members and recording treatments provided [14, 27, 43]. In the reviewed Vanuatu study, 12 village volunteers were selected and trained as MDA staff who delivered each MDA dose under supervision. A multi-country review of CDIs to control and manage tropical diseases, including malaria, identified this approach as more effective at increasing coverage and achieving the targeted outcome compared to conventional vertical approaches [21, 22]. This approach was also more cost effective and operationally efficient with community members’ enthusiasm described as pivotal in increasing feasibility and sustainability [22].

Analysing and comparing the community engagement activities is complicated by the diverse study conditions under which the MDAs were undertaken. These included controlled trials, which entailed close monitoring of participants, whereas others were less intensive implementation studies. Aspects of these controlled clinical trials, such as the provision of incentives (and/or healthcare), would not be feasible as part of a larger implementation and only qualified lessons can be drawn from such studies. With regard to incentives, during a multi-country study in Africa, the effects of different incentives types were compared: material incentives, such as gift items, money or T-shirts were less effective than “intrinsic” incentives, such as sense of recognition, the feeling of making a worthwhile contribution and knowledge gained [21, 22].

In most of the reviewed MDAs, community engagement activities focused on promoting the population coverage and facilitating study operations. However, for many researchers, community engagement now encompasses the broader aim of promoting ethical global health research through, for example, socially responsible knowledge production, capacity development and health promotion, such as through changes in health behaviour [19, 56, 57]. From this perspective, community engagement cannot be simply evaluated in terms of its contribution to the study aims, in the case of mass anti-malarial administration, mainly population coverage.

The local social and cultural context also influences MDA coverage and adherence in various ways: for example, community members’ familiarity with anti-malarials, perceptions about the seriousness of malaria and its local prevalence can influences people’s readiness to take medicines when apparently healthy. The nature of the anti-malarial, particularly any adverse events that are associated with it and how they are interpreted with regard to local understandings of illness, is also likely to influence community responses to the intervention. Similarly, the local availability of healthcare prior to the study could influence participation. Political divisions within the target community, perceived or enacted nepotism can foster resentment and objections towards MDA.

Strengths and limitations

This review is the first comprehensive analysis of the published literature on community engagement and population coverage in mass anti-malarial administrations. The findings are limited by the relatively low proportion of articles that documented community engagement activities (45%; 23/51). The findings are also limited by the heterogeneity of study methods, population and study sites. This is particularly relevant in terms of the methods used to calculate population coverage, which was often reported with insufficient detail to ensure fair comparisons.

Conclusion

The reviewed MDAs varied widely by anti-malarial regimen, study design, context, era, community engagement activities, and population coverage. The mean population coverage for the reviewed mass anti-malarial administrations was above 80%, but inadequate reporting of coverage calculation methods complicates comparisons between studies. Various community engagement activities and approaches were described, many of which contained limited or no details. Community engagement plays a major role in achieving high population coverage in mass anti-malarial administrations. Amongst the reviewed articles, coverage was highest when community engagement involved government and community structures, such as in Nicaragua and on Aneityum island. Other factors, such as the social, cultural and study context, may also play an important role but were not investigated by these articles. More research is needed to disentangle the factors influencing population coverage, adherence, “success” in mass anti-malarial administrations and the role of community engagement activities and approaches. Future research must also (1) report in full the methods used to calculate population coverage; (2) provide details of community engagement activities; and (3) evaluate the impact of the local social context as well as the particular community engagement activities and strategies.

References

Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–23.

Mbengue A, Bhattacharjee S, Pandharkar T, Liu H, Estiu G, Stahelin RV, et al. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2015;520:683–7.

WHO. About the emergency response to artemisinin resistance in the Greater Mekong subregion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/greater_mekong/overview/en/. Accessed 4 Sept 2016.

WHO. Activities for the monitoring and containment of artemisinin resistance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/greater_mekong/activities/en/. Accessed 4 Sept 2016.

von Seidlein L, Dondorp A. Fighting fire with fire: mass antimalarial drug administrations in an era of antimalarial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:715–30.

Newby G, Hwang J, Koita K, Chen I, Greenwood B, von Seidlein L, et al. Review of mass drug administration for malaria and its operational challenges. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:125–34.

von Seidlein L, Greenwood BM. Mass administrations of antimalarial drugs. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:452–60.

Hsiang MS, Hwang J, Tao AR, Liu Y, Bennett A, Shanks GD, et al. Mass drug administration for the control and elimination of Plasmodium vivax malaria: an ecological study from Jiangsu province. China. Malar J. 2013;12:383.

De Martin S, von Seidlein L, Deen JL, Pinder M, Walraven G, Greenwood B. Community perceptions of a mass administration of an antimalarial drug combination in The Gambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:442–8.

Dial NJ, Ceesay SJ, Gosling RD, D’Alessandro U, Baltzell KA. A qualitative study to assess community barriers to malaria mass drug administration trials in The Gambia. Malar J. 2014;13:47.

Maude RJ, Socheat D, Nguon C, Saroth P, Dara P, Li G, et al. Optimising strategies for Plasmodium falciparum malaria elimination in Cambodia: primaquine, mass drug administration and artemisinin resistance. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37166.

Shekalaghe SA, Drakeley C, van den Bosch S, ter Braak R, van den Bijllaardt W, Mwanziva C, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of mass drug administration with a gametocytocidal drug combination to interrupt malaria transmission in a low endemic area in Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:247.

White NJ. The role of anti-malarial drugs in eliminating malaria. Malar J. 2008;7(Suppl 1):S8.

Kaneko A. A community-directed strategy for sustainable malaria elimination on islands: short-term MDA integrated with ITNs and robust surveillance. Acta Trop. 2010;114:177–83.

Bhullar N, Maikere J. Challenges in mass drug administration for treating lymphatic filariasis in Papua, Indonesia. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:70.

Cantey PT, Rout J, Rao G, Williamson J, Fox LM. Increasing compliance with mass drug administration programs for lymphatic filariasis in India through education and lymphedema management programs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e728.

Cheah PY, White NJ. Antimalarial mass drug administration: ethical considerations. Int Health. 2016;8:235–8.

Tindana PO, Singh JA, Tracy CS, Upshur RE, Daar AS, Singer PA, et al. Grand challenges in global health: community engagement in research in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e273.

CTSA. Clinical and translational science awards consortium. Principles of community engagement. 2nd ed. NIH Publication No 11-7782. 2011.

Atkinson JA, Vallely A, Fitzgerald L, Whittaker M, Tanner M. The architecture and effect of participation: a systematic review of community participation for communicable disease control and elimination. Implications for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2011;10:225.

WHO special programme for research and training in tropical diseases. Community-directed interventions for major health problems in Africa: a multi-country study: final report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

CDI Study Group. Community-directed interventions for priority health problems in Africa: results of a multicountry study. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:509–18.

Poirot E, Skarbinski J, Sinclair D, Kachur SP, Slutsker L, Hwang J. Mass drug administration for malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD008846.

Dola SK. Mass drug administration as a supplementary attack measure in malaria eradication programme. East Afr Med J. 1974;51:529–31.

Lwin KM, Imwong M, Suangkanarat P, Jeeyapant A, Vihokhern B, Wongsaen K, et al. Elimination of Plasmodium falciparum in an area of multi-drug resistance. Malar J. 2015;14:319.

Berberian DA, Dennis EW. Field experiments with chloroquine diphosphate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1948;28:755–76.

Garfield RM, Vermund SH. Changes in malaria incidence after mass drug administration in Nicaragua. Lancet. 1983;2:500–3.

Gribben G. Mass treatment with plasmoquine. BMJ. 1933;3802:919–20.

Handerson LH. Prophylaxis of malaria in the Sudan, with special reference to the use of plasmoquine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1934;28:157–64.

Garfield RM, Vermund SH. Health education and community participation in mass drug administration for malaria in Nicaragua. Soc Sci Med. 1986;22:869–77.

Pribadi W, Muzaham F, Santoso T, Rasidi R, Rukmono B. The implementation of community participation in the control of malaria in rural Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1986;17:371–8.

Clyde DF. Malaria control in Tanganyika under the German administration. I. E. East Afr Med J. 1961;38:27–42.

Charles LJ, Van Der Kaay HJ, Vincke IH, Brady J. The appearance of pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum following self-medication by a rural community in Ghana. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;26:103–8.

Baukapur SN, Babu CJ. A focal outbreak of malaria in Valsad district, Gujarat state. J Commun Dis. 1984;16:268–72.

Kaneko A, Taleo G, Kalkoa M, Yamar S, Kobayakawa T, Bjorkman A. Malaria eradication on islands. Lancet. 2000;356:1560–4.

Butler FA. Malaria control program on a South Pacific base. US Nav Med Bull. 1943;41:1603–12.

Sehgal JK. Progress of malaria eradication in Orissa State during 1965–1966. Bull Ind Soc Mal Com Dis. 1968;5:88–93.

Dapeng L, Leyuan S, Xili L, Xiance Y. A successful control programme for falciparum malaria in Xinyang, China. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:100–2.

Gabaldon A, Guerrero L. An attempt to eradicate malaria by the weekly administration of pyrimethamine in areas of out-of-doors transmission in Venezuela. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1959;8:433–9.

Roberts JM. The control of epidemic malaria in the highlands of Western Kenya. I. Before the campaign. J Trop Med Hyg. 1964;67:161–8.

Cheah PY, Lwin KM, Phaiphun L, Maelankiri L, Parker M, Day NP, et al. Community engagement on the Thai–Burmese border: rationale, experience and lessons learnt. Int Health. 2010;2:123–9.

von Seidlein L, Walraven G, Milligan PJ, Alexander N, Manneh F, Deen JL, et al. The effect of mass administration of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine combined with artesunate on malaria incidence: a double-blind, community-randomized, placebo-controlled trial in The Gambia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:217–25.

Song J, Socheat D, Tan B, Dara P, Deng C, Sokunthea S, et al. Rapid and effective malaria control in Cambodia through mass administration of artemisinin–piperaquine. Malar J. 2010;9:57.

Doi H, Kaneko A, Panjaitan W, Ishii A. Chemotherapeutic malaria control operation by single dose of fandisar plus primaquine in North Sumatra, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1989;20:341–9.

Archibald HM. Field trials of mass administration of antimalarial drugs in northern Nigeria. World Health Organization; 1960. WHO/MAL/262–11.

Clyde DF. Mass administration of an antimalarial drug combining 4-aminoquinoline and 8-aminoquinoline in Tanganyika. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:203–12.

MacCormack CP, Lwihula G. Failure to participate in a malaria chemo suppression programme: North Mara, Tanzania. J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;86:99–107.

Kaseje DC, Sempebwa EK. An integrated rural health project in Saradidi, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28:1063–71.

Head BW. Community Engagement: participation on Whose Terms? Aust J Political Sci. 2007;42:441–54.

Rifkin SB. Paradigms lost: toward a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta Trop. 1996;61:79–92.

Greenough P. Intimidation, coercion and resistance in the final stages of the South Asian smallpox eradication campaign, 1973–1975. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:633–45.

Rieckmann KH. The chequered history of malaria control: are new and better tools the ultimate answer? Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:647–62.

Purdey AF, Adhikari GB, Robinson SA, Cox PW. Participatory health development in rural Nepal: clarifying the process of community empowerment. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:329–43.

Aregawi M, Smith SJ, Sillah-Kanu M, Seppeh J, Kamara AR, Williams RO, et al. Impact of the mass drug administration for malaria in response to the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. Malar J. 2016;15:480.

Kuehne A, Tiffany A, Lasry E, Janssens M, Besse C, Okonta C, et al. Impact and lessons learned from mass drug administrations of malaria chemoprevention during the Ebola Outbreak in Monrovia, Liberia, 2014. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161311.

Adhikari B, Mishra SR, Raut S. Rebuilding earthquake struck Nepal through community engagement. Front Public Health. 2016;4:121.

Lavery JV. Putting international research ethics guidelines to work for the benefit of developing countries. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2004;4:319–36.

Kingsbury AN, Amies CR. A field experiment on the value of plasmoquine in the prophylaxis of malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1931;25:159–72.

Kligler IJ, Mer G. Periodic intermittent treatment with chinoplasmine as a measure of malaria control in a hyperendemic area. Riv Malariol. 1931;10:425–38.

White RS, Adhikari AK. Anti-gametocyte treatment combined with anti-larval malaria control. Rec Malar Surv Ind. 1934;4:77–94.

Ray AP. Prophylactic use of paludrine in a tea estate. Indian J Malariol. 1948;2:35–66.

Banerjea R. The control of malaria in a rural area of West Bengal. Indian J Malariol. 1949;3:371–86.

Van Goor WT, Lodens JG. Clinical malaria prophylaxis with proguanil. Doc Neerl Indones Morbis Trop. 1950;2:62–81.

Norman T. An investigation of the failure of proguanil prophylaxis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:653–5.

Archibald HM, Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Suppression of malaria with pyrimethamine in Nigerian school children. Bull World Health Organ. 1956;15:775–84.

Clyde DF, Webbe G, Shute GT. Single dose pyrimethamine treatment of Africans during a malaria epidemic in Tanganyika. East Afr Med J. 1958;35:23–9.

Van Dijk W. Mass chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine additional to DDT indoor spraying. Trop Geogr Med. 1958;10:379–84.

Afridi MK, Rahim A. Further observation on the interruption of malaria transmission with single dose of pyrimethamine (daraprim). Riv Parassitol. 1959;20:229–42.

Van Dijk W. Mass treatment of malaria with chloroquine: results of a trial in Inanwatan. Trop Geogr Med. 1961;13:351–6.

Metselaar D. Seven years’ malaria research and residual house spraying in Netherlands New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961;10:327–34.

Ho C. Studies on malaria in new China. Chin Med J. 1965;84:491–7.

Ossi GT. An epidemic in the life of a malaria eradication programme. Bull Endem Dis. 1967;9:5–18.

Singh MV, Agarwala RS, Singh KN. Epidemiological study of focal outbreak of malaria in consolidation phase area and evaluation of remedial measures in Uttar Pradesh (India). Bull Ind Soc Mal Com Dis. 1968;5:207–20.

Lakshmanacharyulu T, Guha AK, Kache SR. Control of malaria epidemics in a river valley project. Bull Ind Soc for Mal Com. 1968;5:94–105.

Onori E. Experience with mass drug administration as a supplementary attack measure in areas of vivax malaria. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47:543–8.

Najera JA, Shidrawi GR, Storey J, Lietaert PEA. Mass drug administration and DDT indoor-spraying as antimalarial measures in the northern savanna of Nigeria. Malar Bull World Health Organ. 1973;73:1–34.

Schliessmann DJ, Joseph VR, Solis M, Carmichael GT. Drainage and larviciding for control of a malaria focus in Haiti. Mosq News. 1973;33:371–8.

Paik HY. Problem areas in the malaria eradication programme in the British Solomon Islands. PNG Med J. 1974;17:111–5.

Kondrashin AV, Sanyal MC. Mass drug administration in Andhra Pradesh in areas under Plasmodium falciparum containment programme. J Commun Dis. 1985;17:293–9.

Strickland GT, Khaliq AA, Sarwar M, Hassan H, Pervez M, Fox E. Effects of Fansidar on chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:61–5.

Hii JL, Vun YS, Chin KF, Chua R, Tambakau S, Binisol ES, et al. The influence of permethrin-impregnated bednets and mass drug administration on the incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children in Sabah, Malaysia. Med Vet Entomol. 1987;1:397–407.

Babione RW. Epidemiology of malaria eradication. II. Epidemiology of malaria eradication in Central America: a study of technical problems. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1966;56:76–90.

Chaudhuri RN, Janardan Poti S. Suppressive treatment of malaria; with statistical analysis. Indian J Malariol. 1950;4:115–33.

Edeson JF, Wharton RH, Wilson T, Reid JA. An experiment in the control of rural malaria in Malaya. Med J Malaya. 1957;12:319–47.

Omer AH. Species prevalence of malaria in northern and southern Sudan, and control by mass chemoprophylaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:858–63.

Authors’ contributions

BA, NJ, LvS study design; literature search BA, NJ and GN; analysis and interpretation of the results BA, NJ, CP, LvS, PYC; BA and NJ wrote the paper and was revised by BA, LvS, CP and PYC with all authors’ substantial intellectual contributions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Jacqueline Deen for her review and valuable suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data pertaining to this study are within the manuscript and the supporting files.

Funding

This study is part of the Targeted Malaria Elimination programme supported by the Wellcome Trust (101148/Z/13/Z) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF OPP1081420). The Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit is funded by the Wellcome Trust (106698/Z/14/Z). Phaik Yeong Cheah is funded by a Wellcome Trust Engaging Science Grant (105032/Z/14/Z).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Bipin Adhikari and Nicola James contributed equally to this work

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Adhikari, B., James, N., Newby, G. et al. Community engagement and population coverage in mass anti-malarial administrations: a systematic literature review. Malar J 15, 523 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1593-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1593-y