Abstract

Background

The market for recombinant proteins is on the rise, and Gram-positive strains are widely exploited for this purpose. Bacillus subtilis is a profitable host for protein production thanks to its ability to secrete large amounts of proteins, and Lactococcus lactis is an attractive production organism with a long history in food fermentation.

Results

We have developed a synbio approach for increasing gene expression in two Gram-positive bacteria. First of all, the gene of interest was coupled to an antibiotic resistance gene to create a growth-based selection system. We then randomised the translation initiation region (TIR) preceding the gene of interest and selected clones that produced high protein titres, as judged by their ability to survive on high concentrations of antibiotic. Using this approach, we were able to significantly increase production of two industrially relevant proteins; sialidase in B. subtilis and tyrosine ammonia lyase in L. lactis.

Conclusion

Gram-positive bacteria are widely used to produce industrial enzymes. High titres are necessary to make the production economically feasible. The synbio approach presented here is a simple and inexpensive way to increase protein titres, which can be carried out in any laboratory within a few days. It could also be implemented as a tool for applications beyond TIR libraries, such as screening of synthetic, homologous or domain-shuffled genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The advent of recombinant protein technology has enabled commercial applications for biopharmaceutical proteins and industrial biocatalysts not possible when the only option was to extract proteins from their original hosts. The enzyme market in particular has bloomed as a result of the production costs approaching those of the chemical industry [1]. To achieve low costs, enzymes are produced in large quantities by exploiting cell factories and large-scale bioreactors, but continuous improvements in the design of cell factories are needed to keep the production competitive and open markets for new products [2].

Various rational engineering approaches for cell factories are routinely employed to improve production. In the initial process a suitable expression host needs to be selected. Despite the documented role of Escherichia coli in molecular biology, other bacterial expression systems have been explored in biotechnology, taking advantage of divergent metabolism, secretion capability and biosafety of their protein-based products [3, 4]. Amongst them, various Gram-positive bacteria are of great interest due to e.g. their highly efficient protein secretion and GRAS status. Bacillus subtilis is routinely used industrially for its ability to secrete large amount of enzymes, which simplifies protein recovery and purification, leading to yields up to 20–25 g/L [5]. Lactococcus lactis has a long history of use in food microbiology and in the dairy industry [6], and it has lately risen as an alternative for production of membrane proteins [7, 8], secreted proteins [9, 10] and plant-based proteins and secondary metabolites [11,12,13].

Previously we have shown that protein production in a Gram-negative bacterium can be significantly increased by synthetically evolving a part of the translation initiation region (TIR) [14]. In expression clones the TIR extends from the region upstream of the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence to the 5th or 6th codon of the gene of interest [15]. Whilst most TIRs function, they can support higher production titres if they are evolved with an appropriate selection pressure—for example by creating large libraries of randomised TIRs and selecting one that produces the most protein [16, 17].

Yet screening approaches for those libraries are limited. High throughput screening methods like fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) or droplet microfluidics enable the assessment of large libraries [18,19,20] but their use is restricted to phenotypes associated with a fluorophore to effectively screen for e.g. increased protein production [21]. Fusions with reporter proteins, such as fluorescent proteins, can also compromise the expression, solubility and bioactivity of a protein and are not suitable in industrial set-ups [22, 23]. The availability of other types of biosensors is limited and developing one for a new target is a laborious and time consuming process [24].

For this purpose, we have established a phenotypic screening approach for TIR libraries in E. coli [25]. The approach utilises an antibiotic resistance gene that is translationally coupled to the gene of interest. In the bicistronic mRNA design, a hairpin-like structure separates an upstream gene of interest from a downstream antibiotic selection marker, thereby sequestering the SD site of the latter. Only upon efficient translation of the upstream gene, antibiotic resistance is obtained because the helicase activity of the translating ribosome allows expression of the downstream resistance gene (Fig. 1a). In this study we set out to determine if a similar synbio approach for optimising and selecting TIRs, would lead to increased production levels in industrially relevant Gram-positive bacteria.

Testing of a translational coupling device in Bacillus subtilis and Lactococcus lactis. a To asses the efficacy of a specific translational coupling device in B. subtilis and L. lactis an mRNA hairpin structure was sandwiched between the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (gfp, green) and the chloramphenicol resistance gene (CmR, orange). Left side: the predicted structure of the translational coupling device. Presumably, the stem of the mRNA hairpin structure consists of 11 nucleotide pairs comprising the stop codon of the upstream gene (red box) and the start codon of the downstream gene (green box). The ribosome binding site (black box) of the downstream gene is designed to be masked by the secondary mRNA structure. Upper right side: when the upstream gene (green, gfp) is not translated, the mRNA hairpin structure will not be resolved and the ribosome binding site of the downstream gene (orange, CmR) remains inaccessible for the ribosome. Therefore, there is no translation of the downstream gene. Lower right side: when a ribosome translates gfp, the ribosome’s helicase activity will melt the secondary mRNA structure which makes the ribosome binding site accessible and the chloramphenicol resistance gene can be translated. The correlation between protein production, determined as fluorescence normalized for cell density, and chloramphenicol resistance, determined as minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC), was determined for genome-based expression in B. subtilis (b) and for plasmid-based expression in L. lactis (c)

Results

Characterization of a translational coupling device in Gram-positive hosts

We first set out to explore the applicability of a translational coupling design that was previously developed in E. coli [25]. To this end we constructed a plasmid for L. lactis and B. subtilis that contained the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (gfp), coupled by a sequence with hairpin-forming (hp) propensity to a chloramphenicol resistance gene (gfp-hp-CmR) (Fig. 1a).

The gfp-hp-CmR construct was expressed from the nisin-inducible promoter PnisA in a pNZ8048 vector in L. lactis [26]. In B. subtilis a set of four different constitutive promoters of increasing strength (PJ23101, PliaG, PlepA and Pveg [27]) were used and the constructs were integrated into the amyE locus on the chromosome [28]. L. lactis cultures were grown overnight, diluted in the morning and induced with variable concentrations of nisin (0.25–10 ng/mL); B. subtilis cultures were treated the same way, but did not require induction. Fluorescence was measured when the cultures reached late exponential phase and was normalized by cell density. At the same time resistance was assessed by plating on different concentrations of chloramphenicol. In both L. lactis and B. subtilis fluorescence levels showed a linear correlation (R2 > 0.9) with resistance to chloramphenicol, the latter measured as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Fig. 1b, c). This demonstrates that the translational coupling device in combination with a chloramphenicol resistance gene can work over a broad range as a reporter of gene expression in these two Gram-positive model bacteria.

Characterization of translation initiation region libraries in L. lactis and B. subtilis

Next we introduced sequence diversity in a specific part of the translation initiation region (TIR)—an approach that has proven successful for expression optimization in E. coli [14]. In this experiment the six nucleotides upstream of the start codon are randomized and the second and third codon of the open reading frame are concurrently substituted with synonymous codons (Fig. 2a). Depending on the nature of the 2nd and 3rd amino acid in the protein sequence, this system generates a maximum library size of about 150,000 variants and up to 1000-fold variation in gene expression levels in E. coli [14].

A part of the translation initiation region (TIR) affects expression in Bacillus subtilis and Lactococcus lactis. a TIR libraries (NNNNNNATGN*N*N*N*N*N*, see main text for further details) were constructed by PCR, transformed into the host strains and individual library clones were grown to asses the expression level ranges in B. subtilis and L. lactis. Fluorescence normalized by cell density was determined for 96 library clones for B. subtilis (b) and L. lactis (c). The B. subtilis library was expressed from the genome whereas the L. lactis library was expressed from a plasmid

In the case of gfp, a library with about 50,000 variants was constructed in both hosts. In B. subtilis we chose a strong constitutive promoter (Pveg) to control expression of gfp. The library was integrated into the amyE locus on the chromosome using an integrative vector propagated in E. coli. In L. lactis we used the pNZ8048 plasmid with the inducible nisin promoter controlling the expression of gfp. Both libraries were based on the constructs used for the initial characterization of the translational coupling device gfp-hp-CmR. Sequence variation was introduced by PCR using degenerate oligonucleotides that randomized the TIRs. The TIR region of five arbitrary clones from each library were sequenced to validate diversity in the libraries. A total of 96 clones were randomly picked and cultivated. Cultures were back-diluted after overnight incubation, induced when required and expression levels were assayed after 5 h. The fluorescence levels varied greatly amongst the clones with the highest and the lowest gfp-expressing clones differing by up to 1000-fold (Fig. 2b, c). This observation confirms that this part of the TIR is an important determinant of expression levels in a broad range of bacterial species.

Antibiotic-based selection of high-producing variants from TIR libraries

To select for the best TIRs, libraries were plated on solid media with increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol. The amount of colonies appearing on the plates decreased whereas the average fluorescence intensity increased with rising concentrations of antibiotic (Fig. 3a). Clones were randomly picked from the plates, recovered and grown overnight without antibiotic selection before measuring the fluorescence in a microplate reader (Fig. 3b). This analysis showed that the likelihood of isolating a highly fluorescent clone increased with increasing concentrations of antibiotics (Fig. 3c).

Antibiotic selection of maximal protein production in a Gram-positive bacterium. a B. subtilis TIR libraries expressing gfp were grown on agar plates with different chloramphenicol concentrations. GFP production levels on the different antibiotic concentrations were assayed by exposing agar plates to long-wave UV light. Five individual colonies were randomly picked from these plates and assayed for expression levels assessed by fluorescence per cell density in a microplate reader (b, c)

Optimization of industrially relevant proteins

Finally we explored optimization of clones for production of different industrially relevant proteins in the two Gram-positive hosts. For L. lactis we chose to optimize expression of a tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) from Flavobacterium johnsoniae, which is expressed in the cytoplasm and converts tyrosine into p-coumaric acid in a single enzymatic step [29]. For B. subtilis we chose to target a Micromonospora viridifaciens sialidase (SIA), a hydrolase that cleaves the sialic acid residues of glycans [30]. In both cases well-established expression set-ups were used that were reported to result in high expression levels.

We first integrated the selection module hp-CmR downstream of the genes-of-interest into the plasmids used in the previous studies for the corresponding enzyme production [29, 30]. In these experiments, cytoplasmic expression of tal in L. lactis was controlled by the inducible PnisA promoter in a pNZ8048 vector; however, we had to exchange the original chloramphenicol cassette of the vector backbone for an erythromycin resistance gene, to be able to first select for the transformed plasmid then utilize the hp-CmR device for selection of highly expressing variants. Expression of sia in B. subtilis was under control of the strong constitutive P32 promoter and secreted by the aid of a CGTase signal peptide encoded in the replicative pDP66K plasmid. In both experiments, we refer to the TIR in the original construct as the TIRorig.

The TIRorig was then randomized by PCR using degenerate oligonucleotides, employing the same strategy as with the gfp-hp-CmR library. After transformation into the hosts and overnight recovery with the appropriate vector backbone antibiotics in liquid culture, both libraries were back-diluted, induced when required and after 5 h plated on solid media with different concentrations of chloramphenicol. We then determined the colony forming units (CFUs) of each library at different concentrations of chloramphenicol, and compared with the TIRorig clones. In both cases we observed that the library produced more CFUs at higher chloramphenicol concentrations than the original construct (Fig. 4a, b). In addition, we observed a reduction in the amount of colonies appearing on the plates as the antibiotic concentration increased.

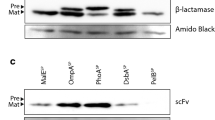

Production optimization of the industrially relevant proteins tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) and sialidase (SIA). a A His-tagged sialidase-encoding sequence was translationally coupled to the chloramphenicol resistance gene. A TIR library was constructed, transformed into B. subtilis and grown with different chloramphenicol concentrations on agar plates. Colony forming units (CFUs) were counted for all concentrations for the library (TIRlib) and the original, non-randomized clone (TIROrig) as control. b A Strep-tagged tal-encoding sequence was translationally coupled to the chloramphenicol resistance gene. A TIR library was constructed, transformed into L. lactis and grown with different chloramphenicol concentrations on agar plates. CFUs were counted for all concentrations for the library (TIRlib) and the original, non-randomized clone (TIRorig) as control. c The sialidase production level in the culture supernatant of the best performing clone (TIRopt) was analyzed by Western blot, using an antibody against a His-tag (left panel). The increase in production was analyzed by densitometry and plotted as the relative protein production compared to the original clone (right panel). d TAL production level of the best performing clone (TIRopt) was analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody against Strep-tag (left panel). The increase in production was analyzed by densitometry and plotted as the relative protein production compared to the original clone (right panel). e Sialidase (TIRopt) was purified via a Ni2+-NTA column and purified product concentration was estimated using a BCA assay (left panel). Product per cell mass and per culture volume was calculated (right panel). The original construct (TIRorig) was used for comparison

Colonies were recovered on 75 μg/mL chloramphenicol for B. subtilis and 15 μg/mL chloramphenicol for L. lactis. Protein levels were assessed by Western blotting using a His-tag antiserum for sialidase and a Strep-tag antiserum for TAL (Fig. 4c, d). In both cases, the clones isolated at the highest antibiotic concentration displayed a higher protein production compared to the TIRorig. Production of TAL in L. lactis was improved by approximately eightfold (Fig. 4d) and production of sialidase in B. subtilis was doubled (Fig. 4c) from approximately 1 to 2 g/L (Fig. 4e). In both cases, activity of the enzymes originating from the optimized TIRopt variants was not compromised at the high level production (Additional file 1: Figure S1A, B).

Discussion

A wide range of industrial applications use enzymes as a sustainable alternative to chemical catalysts. These applications include, but are not limited to, the manufacturing of food, paper, detergents and biofuels [31]. However refinement in production titres rely on enzyme discovery and gene and strain engineering, which are time consuming and labour intensive processes. Existing methods for high throughput screening of gene expression are based on e.g. droplet microfluidics or flow cytometry [18, 20]. Despite being extremely efficient and effective, these platforms are expensive to purchase and operate and their availability is limited to large-scale operations. Other screening methods rely on protein fusions, which might alter parameters such as expression, solubility and turnover rate [22]. To address this issue, we developed a simple growth based selection system based on translational coupling of an antibiotic resistance gene with the upstream gene sequence that leaves the protein of interest unaltered. Different from previous attempts, our system focuses on Gram-positive bacteria [25], works on genomically integrated targets and does not require tagging of the protein of interest [32]. Nonetheless, tags can be purposefully added to the protein if desired.

We first explored the relationship between gene expression and antibiotic resistance. A low correlation could indicate poor protein folding or poor melting of the mRNA hairpin. However, the correlation coefficient was above 0.9 in both hosts, which demonstrates that antibiotic sensitivity is tuneable and that the system responds linearly to the gene expression levels tested. Differences in the dynamic range of screenable chloramphenicol concentrations were observed between the two hosts; the smaller dynamic range in B. subtilis may be due to the initial choice of a poor-performing TIR for gfp. The expression was very low, even when controlled by a strong promoter. Once we built a combinatorial library randomizing the TIR, the best expressing variants improved in protein production by eightfold over the variant we used to characterize the mRNA hairpin.

Protein production constructs are often assembled in replicative or integrative plasmids. Previous work has shown that the junction created between the vector and the coding sequence can result in different levels of expression depending on e.g. the restriction site used [14]. The variability is not completely explained by the free energy (∆G) associated with mRNA folding and seems to be context specific, meaning that the cloning scar will affect the levels of expression in a manner that is not robustly computationally predictable. The creation of a TIR library circumvents the problem by optimizing the expression of a gene directly in the system in which it will be expressed.

Here we demonstrate the effectiveness of removing the cloning scar bias by improving the production of two industrially relevant proteins. We chose to optimize TAL in L. lactis, due to the wide range of compounds of biotechnological interest that are produced from the intermediate p-coumaric acid; these include for example the flavonoid naringenin or the stilbene resveratrol [11, 29]. For B. subtilis we optimized the production of a sialidase, as their enzymatic activity gained interest in relation to treatment of spinal cord injuries and there was a recent attempt to improve their activity and production using B. subtilis [30]. Both genes were cloned into vectors using traditional restriction enzyme based cloning and were already expressed with high yield. After creating a combinatorial library that modifies the TIR, we could select variants that produced two to eightfold more protein than the original clones. Most importantly, the sialidase production level in B. subtilis increased from 1 to 2 g/L in a 50 mL shake flask experiment, demonstrating that the specific TIR optimization and selection tool can achieve high yields, in the range of industrial titer levels, even when carried out in low density cultures. A substantial increase in yield is expected in industrial fed-batch fermentations.

The tool we developed has the potential to be transferred to other less amenable members of the Bacillus or Lactococcus families. With decreasing cost of DNA synthesis and the increasing interest in Gram-positive cell factories, different types of combinatorial libraries can be coupled with this selection system to screen for variants that produce a protein. Some examples are error prone PCR, promoter libraries, DNA shuffling or other in vitro and in vivo methodologies that generate genetic variability. The screening process is simple, inexpensive and can be carried out in a few days in any molecular biology laboratory and therefore presents an attractive alternative to advanced screening methodologies.

Conclusion

We developed a selection-based system to screen for synthetically evolved TIRs in Gram-positive hosts. The system responds linearly to increasing concentrations of antibiotic by preventing growth of sub-optimal library variants. Using the selection tool, we demonstrate improved expression of industrially relevant proteins in two cell factory hosts, namely TAL in L. lactis and a sialidase in B. subtilis.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Lactococcus lactis strain NZ9000 ∆ hsd was used for all experimental procedures. Cells were grown at 30 °C in M17 broth (BD Difco, San Jose, CA, USA) supplemented with 1% glucose (GM17), without shaking. Electro competent cells were prepared as previously described [33]. Cultures were supplemented with 5 µg/mL erythromycin or 5 µg/mL chloramphenicol to select for plasmid presence, unless otherwise stated. Cultures were induced with 1.5 ng/mL nisin, unless otherwise stated.

Bacillus subtilis strain SCK6 (1A976 http://www.bgsc.org) was used for expression experiments. Cloning, library construction and propagation of plasmids were performed in E. coli NEB5α (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). B. subtilis was grown in lysogeny broth (LB) at 37 °C shaking (250 rpm). The antibiotics neomycin (5 µg/mL), kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and erythromycin (5 µg/mL) were supplemented when necessary. Transformation of integration vectors into B. subtilis was performed with chemically competent cells as previously described [34]. Correct genome integrations were confirmed by colony PCR and sequencing.

Plasmids and strain construction

Plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3. All constructs were made with uracil excision cloning as previously described [35].

Plasmids used in L. lactis are based on pNZ8048 from the NIsin Controlled gene Expression (NICE) system [26] and expression was controlled by the inducible nisin promoter. Translationally coupled versions were constructed using the standard chloramphenicol acetyltransferase resistance gene derived from pNZ8048 [26]. Hairpins were introduced by USER cloning using overlapping oligonucleotide tails coding for the hairpin [35, 36]. The resulting plasmids pNZ-tal-hp-CmR was built by adding the hp-CmR module to the pNZ_FjTAL described previously [29]. The plasmid pNZ-gfp-hp-CmR was built in two steps: first by cloning a GFP folding reporter [37] into pNZ8048, using primers 1 and 2. In a second step the module hp-CmR was added to the vector.

Bacillus subtilis plasmids were constructed in E. coli NEB5α (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), purified and subsequently transformed and integrated into B. subtilis. Integration vectors were based on the pDG268 plasmid, with integration in the amyE locus. Transcription was controlled by four different constitutive promoters of increasing strength: PJ23101, PliaG, PlepA, and Pveg [27]. All four promoters variants were used to construct pDG-GFP-hp-CmR. Promoters were amplified from the B. subtilis genome. The synthetic promoter pJ23101 was inserted into the plasmid using two overlapping oligonucleotides by PCR.

The replicative vector pDP66K-SIA-hp-CmR was constructed by adding the hp-CmR module to the plasmid pDP66K-Mv [30] which uses the promoter P32 to drive transcription.

Library construction

For the construction of TIR libraries a degenerated forward oligonucleotide specific for the gene of interest was designed. The six nucleotides upstream of the start codon were changed to all possible combinations whereas the six nucleotides downstream the start codon were changes to all possible synonymous codons.

Libraries for L. lactis were constructed by amplification of the whole pNZ-derived plasmid using the degenerated forward oligonucleotide and a reverse oligonucleotide with a pairing USER cloning overlap. The plasmid library was built by amplifying the template plasmid containing gfp, gfp-hp-CmR or tal-hp-CmR with the degenerate oligonucleotides and circularized using USER cloning as described elsewhere [35]. Libraries were transformed directly into L. lactis with no intermediate steps. The reference construct for the tal gene, here referred to as the TIRorig clone, was previously described [29].

Libraries for B. subtilis were constructed in E. coli MC1061 by amplification of the whole pDG268neo or pDP66K-Mv plasmids using degenerated forward oligonucleotides and reverse oligonucleotides sharing 15 nucleotide homology with the forward oligonucleotide. Q5 polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used to amplify the template plasmid containing gfp, gfp-hp-CmR or sia-hp-CmR. Library construction was performed as described before [14]. The reference construct for the sia gene, here referred to as the TIRorig clone, was previous described [30].

Expression and selection

Expression of individual L. lactis clones, were assayed using overnight cultures prepared by inoculating a single colony in 5 mL GM17 supplemented with respective antibiotics and incubated at 30 °C without shaking. Cultures were then back-diluted (1:50) into 5 mL of GM17 media containing the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 30 °C without shaking. At OD600 0.3–0.6 cultures were induced with 1.5 ng/mL nisin and incubated for 3 h.

For the assessment of individual clones, B. subtilis overnight cultures were prepared by inoculating a single colony in 5 mL LB media supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. Cultures were then back-diluted (1:50) into 5 mL of LB media containing the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 5 or 23 h.

Ca. 1 μg of plasmid library was transformed into L. lactis or B. subtilis using standard protocols [33, 34]. Cells were recovered for 1 h after transformation in GM17MC or LB media, transferred to GM17 or LB media supplemented with antibiotics and grown overnight at 30 °C for L. lactis and 37 °C for B. subtilis.

Lactococcus lactis cultures were then back-diluted (1:50) into 10 mL GM17 media containing the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 30 °C. Cultures were induced at OD600 0.3–0.6 and after 5 h 0.2 OD units were plated on GM17 plates with increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol and incubated at 30 °C overnight.

After overnight incubation, B. subtilis cultures were back-diluted (1:50) into 5 mL LB media containing the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. 5 h after dilution, OD600 was measured and 0.2 OD units of cells were then plated on LB agar plates containing different concentrations of chloramphenicol and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Selection was performed as previously described [36]. Selected expression variants were sequenced.

MIC determination

For L. lactis MIC determinations, 5 mL GM17 media with 5 µg/mL erythromycin were inoculated with a single colony containing pNZGFP-hp-CmR and grown overnight at 30 °C. Cultures were then back-diluted (1:50) into 10 mL GM17 media supplemented with 5 µg/mL erythromycin, and their growth monitored. At OD 0.3 the culture was split into 8 different 2 mL eppendorf tubes and induced with different concentrations of nisin (0; 0.25; 0.5; 0.75; 1; 1.5; 5 or 10 ng/mL). Cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 2 h and 0.01 ODU of each culture was transferred to a 96 wells plate (Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria) containing 200 μL GM17 media (ca. 5 × 106 cfu/mL), and a serial dilution of chloramphenicol and respective concentrations of nisin as inducer. Plates were incubated for 15 h at 30 °C.

For Bacillus subtilis MIC determinations, 5 mL LB media were inoculated with 4 strains that constitutively expressed gfp-hp-CmR and grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking. Cultures were then back-diluted (1:100) into 5 mL LB media containing the appropriate antibiotic in a 24-deep well plate (EnzyScreen, Heemstede, Netherlands). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking. After 2 h, 10 μL of each culture was transferred to a 96 well plate (Greiner, Austria) containing 100 μL LB media (ca. 5 × 105 cfu/mL) and a serial dilution of chloramphenicol. Plates were incubated for 18 h.

To assess translational coupling, fluorescence (Ex: 485 nm, Em: 516 nm for GFP) and OD600 were measured in an MX plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA). The MIC value was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration at which the final OD600 represented less than 10% of the entire population after background correction. Each MIC experiment was conducted with biological triplicates.

Protein detection and quantification

Western Blot analysis was performed by resuspending L. lactis grown as described above in 50% volume of CelLytic B (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with lysozyme, egg white (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA), benzonase nuclease (≥ 250 units/μL, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Roche cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated for 1 h before the samples were sonicated. An aliquot of 20 µL of each sample was incubated for 1 h with 1 µL of a 1:10 dilution of CY5 dye (Amersham quick stain, GE healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) for total protein quantification. The sample was then mixed with the same volume of 5 × reducing sample buffer and heated to 95 °C for 5 min for protein denaturation. 0.05 ODU of the samples were loaded onto a 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN-TGX gel (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and run for 35 min at 175 V.

For B. subtilis, 10 μL of supernatant were mixed with 5 μL of 5× reducing sample buffer and heated to 95 °C for 5 min for protein denaturation. 10 μL of the samples were loaded onto a 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN-TGX gel (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and run for 35 min at 175 V.

Proteins were transferred from the protein gel to a nitrocellulose membrane using the iBlot® dry blotting system (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 25 V for 7 min. The proteins were detected with the help of antigen-specific antibodies.

For B. subtilis sialidase an anti-His antibody (1:1000; Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used. The antibody was diluted in 5% w/v skim milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% v/v Tween-20), the secondary antibody was diluted in TBS-T. For L. lactis an anti-Strep (1:10,000, Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) directly coupled to HRP was used.

The HRP-coupled antibody was visualized using Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The chemoluminescence signal was detected using a G:Box bioimager (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). The resulting images were analysed by densitometry using the Fiji software [38].

Sialidase protein purification

50 mL LB broth supplemented with 50 µg/mL kanamycin was inoculated with an overnight culture of B. subtilis SCK6 transformed with pDP66K-SIA-hp-CmR to an OD600 of 0.05. Cells were grown for 23 h at 37 °C with shaking (250 rpm). After 23 h the supernatant was harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 15 min and 4 °C and passed through a 0.45 μm filter (Frisenette ApS, Knebel, Denmark) and a 0.20 μm filter (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). The filtered supernatant was then concentrated using a 10 K Amicon concentrator (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), mixed with 10 mL purification buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and again concentrated. The final concentrate was subjected to a Ni–NTA spin column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The column was washed twice with 600 μL of washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and finally protein was eluted twice with 300 μL elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). To reduce imidazole concentration several cycles of concentrating and diluting in storage buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) were performed using a 10 K Amicon concentrator (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The final volume was adjusted to 200 μL and protein concentration was estimated using BCA assay (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). BSA was used as standard.

Sialidase activity assay

To determine activity of the sialidase, supernatant and concentrated supernatant of expression cultures of the original and optimized clones and purified proteins were diluted in 50 mM phosphate-citrate buffer pH 7.0. The enzymatic reaction was started by addition of the substrate pNP-Neu5Ac (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 0.75 mM in a 100 μL reaction. Absorbance at 410 nm was monitored continuously for 1 h in an MX plate reader (Biotek, USA). The reaction rate was calculated from the slope of the initial linear section of the curve.

TAL activity assay

The TAL activity was measured as described by Jendersen and colleagues [29]. Briefly, expression of tal was induced with 1.5 ng/mL nisin in chemically defined media (CDM) as described above. Cultures were grown at 30 °C for 16 h, harvested at 13000 g and the supernatant was recovered. The concentration of p-coumarate was measured by HPLC using a gradient method with two solvents (0.1% ammonium formate and acetonitrile) and quantified measuring absorbance at 290 nm.

Abbreviations

- Cm:

-

chloramphenicol

- HRP:

-

horse radish peroxidase

- LB:

-

lysogeny broth

- NICE:

-

NIsin Controlled gene Expression

- OD600 :

-

optical density at 600 nm

- SIA:

-

sialidase

- SD:

-

Shine Dalgarno

- TAL:

-

tyrosine ammonia lyase

- TIR:

-

translation initiation region

References

Cherry JR, Fidantsef AL. Directed evolution of industrial enzymes: an update. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:438–43.

Gavrilescu M, Chisti Y. Biotechnology—a sustainable alternative for chemical industry. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:471–99.

Ferrer-Miralles N, Villaverde A. Bacterial cell factories for recombinant protein production; expanding the catalogue. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:113.

Chen R. Bacterial expression systems for recombinant protein production: E. coli and beyond. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:1102–7.

van Dijl JM, Hecker M. Bacillus subtilis: from soil bacterium to super-secreting cell factory. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:3.

Song AAL, In LLA, Lim SHE, Rahim RA. A review on Lactococcus lactis: from food to factory. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:55.

Kunji ERS, Slotboom DJ. Lactococcus lactis as host for overproduction of functional membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA). 2003;1610(1):97–108.

Monné M, Chan KW, Slotboom DJ. Functional expression of eukaryotic membrane proteins in Lactococcus lactis. Protein Sci. 2005;14(12):3048–56.

Morello E, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Llull D, Solé V, Miraglio N, Langella P, et al. Lactococcus lactis, an efficient cell factory for recombinant protein production and secretion. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;14:48–58.

Le Loir Y, Azevedo V, Oliveira SC, Freitas DA, Miyoshi A, Bermudez-Humaran LG, et al. Protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis: an efficient way to increase the overall heterologous protein production. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;13:1–13.

Dudnik A, Almeida AF, Andrade R, Avila B, Bañados P, Barbay D, et al. BacHBerry: BACterial hosts for production of bioactive phenolics from bERRY fruits. Rev: Phytochem; 2017.

Song AA, Abdullah JO, Abdullah MP, Shafee N, Rahim RA. Functional expression of an orchid fragrance gene in Lactococcus lactis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(2):1582–97.

Martinez-Cuesta MC, Gasson MJ, Narbad A. Heterologous expression of the plant coumarate: coA ligase in Lactococcus lactis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2005;40(1):44–9.

Mirzadeh K, Martínez V, Toddo S, Guntur S, Herrgård MJ, Elofsson A, et al. Enhanced protein production in Escherichia coli by optimization of cloning scars at the vector-coding sequence junction. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:959–65.

Laursen BS, Sørensen HP, Mortensen KK, Sperling-Petersen HU. Initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:101–23.

Warner JR, Reeder PJ, Karimpour-Fard A, Woodruff LBA, Gill RT. Rapid profiling of a microbial genome using mixtures of barcoded oligonucleotides. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:856–62.

Wang HH, Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Sun ZZ, Xu G, Forest CR, et al. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature. 2009;460:894–8.

Sjostrom SL, Bai Y, Huang M, Liu Z, Nielsen J, Joensson HN, et al. High-throughput screening for industrial enzyme production hosts by droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2014;14:806–13.

Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene. 1996;173:33–8.

Yang G, Withers SG. Ultrahigh-throughput FACS-based screening for directed enzyme evolution. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2704–15.

Dietrich JA, McKee AE, Keasling JD. High-throughput metabolic engineering: advances in small-molecule screening and selection. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:563–90.

Chen X, Zaro JL, Shen WC. Fusion protein linkers: property, design and functionality. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:1357–69.

Linares DM, Geertsma ER, Poolman B. Evolved Lactococcus lactis strains for enhanced expression of recombinant membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:45–55.

Schallmey M, Frunzke J, Eggeling L, Marienhagen J. Looking for the pick of the bunch: high-throughput screening of producing microorganisms with biosensors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2014;26:148–54.

Rennig M, Martinez V, Mirzadeh K, Dunas F, Röjsäter B, Daley DO, et al. TARSyn: tunable antibiotic resistance devices enabling bacterial synthetic evolution and protein production. ACS Synth Biol. 2018;7:432–42.

Kuipers OP, De Ruyter PGGA, Kleerebezem M, De Vos WM, Ruyter P, Kleerebezem M, et al. Quorum sensing-controlled gene expression in lactic acid bacteria. J Biotechnol. 1998;64:15–21.

Radeck J, Kraft K, Bartels J, Cikovic T, Dürr F, Emenegger J, et al. The Bacillus BioBrick Box: generation and evaluation of essential genetic building blocks for standardized work with Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Eng. 2013;7:29.

Jers C, Kobir A, Søndergaard EO, Jensen PR, Mijakovic I. Bacillus subtilis two-component system sensory kinase DegS is regulated by serine phosphorylation in its input domain. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14653.

Jendresen CB, Stahlhut SG, Li M, Gaspar P, Siedler S, Förster J, et al. Highly active and specific tyrosine ammonia-lyases from diverse origins enable enhanced production of aromatic compounds in bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:4458–76.

Jers C, Guo Y, Kepp KP, Mikkelsen JD. Mutants of micromonospora viridifaciens sialidase have highly variable activities on natural and non-natural substrates. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2015;28:37–44.

Singh R, Kumar M, Mittal A, Mehta PK. Microbial enzymes: industrial progress in 21st century. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:1–15.

Mendez-Perez D, Gunasekaran S, Orler VJ, Pfleger BF. A translation-coupling DNA cassette for monitoring protein translation in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2012;14:298–305.

Holo H, Nes IF. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol Am Soc Microbiol. 1989;55:3119.

Zhang XZ, Zhang YHP. Simple, fast and high-efficiency transformation system for directed evolution of cellulase in Bacillus subtilis. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:98–105.

Cavaleiro AM, Kim SH, Seppälä S, Nielsen MT, Nørholm MHH. Accurate DNA assembly and genome engineering with optimized uracil excision cloning. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:1042–6.

Rennig M, Daley DO, Nørholm MHH. Selection of highly expressed gene variants in Escherichia coli using translationally coupled antibiotic selection markers. In: Jensen MK, Keasling JD, editors. Synthetic metabolic pathways: methods and protocols. 1st ed. New York: Humana Press; 2018.

Waldo GS, Standish BM, Berendzen J, Terwilliger TC. Rapid folding assay using green fluorescent protein. 1999;17(7):691–5.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open source platform for biological image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82.

Authors’ contributions

RF, MR, DOD and MHHN designed the experiments. RF performed the experiments in L. lactis. MR, RF and CHR performed the experiments in B. subtilis. RF and MR wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Carsten Jers for discussion and advice in the B. subtilis part of this study and sharing of plasmids or strains when needed, and Alexey Dudnik for general discussion on L. lactis troubleshooting and sharing of plasmids or strains when needed.

Competing interests

The authors declare possible competing interests. RF, MR, DOD and MHHN have submitted a patent application on the use of the hairpin coupling mechanism in prokaryotes. DOD has submitted a patent on the TIR optimization. CHR declares no competing financial interests.

Availability of data and materials

All material available upon request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (BacHBerry, Project No. FP7-613793).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Supplementary information for a synbio approach for selection of highly expressed gene variants in Gram-positive bacteria.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferro, R., Rennig, M., Hernández-Rollán, C. et al. A synbio approach for selection of highly expressed gene variants in Gram-positive bacteria. Microb Cell Fact 17, 37 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0886-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-018-0886-y