Abstract

Background

Lower body mass index (BMI) and weight loss have been associated with worse outcomes in some studies in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. We analyzed outcomes in subgroups by BMI at baseline and associations between weight change and outcomes in subjects with progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) in the INBUILD trial.

Methods

Subjects with PPF other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis were randomized to receive nintedanib or placebo. In subgroups by BMI at baseline (< 25, ≥ 25 to < 30, ≥ 30 kg/m2), we analyzed the rate of decline in FVC (mL/year) over 52 weeks and time-to-event endpoints indicating disease progression over the whole trial. We used a joint modelling approach to assess associations between change in weight and the time-to-event endpoints.

Results

Among 662 subjects, 28.4%, 36.6% and 35.0% had BMI < 25, ≥ 25 to < 30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively. The rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks was numerically greater in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 (nintedanib: − 123.4, − 83.3, − 46.9 mL/year, respectively; placebo: − 229.5; − 176.9; − 171.2 mL/year, respectively). No heterogeneity was detected in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline among these subgroups (interaction p = 0.83). In the placebo group, in subjects with baseline BMI < 25, ≥ 25 to < 30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively, 24.5%, 21.4% and 14.0% of subjects had an acute exacerbation or died, and 60.2%, 54.5% and 50.4% of subjects had ILD progression (absolute decline in FVC % predicted ≥ 10%) or died over the whole trial. The proportions of subjects with these events were similar or lower in subjects who received nintedanib versus placebo across the subgroups. Based on a joint modelling approach, over the whole trial, a 4 kg weight decrease corresponded to a 1.38-fold (95% CI 1.13, 1.68) increase in the risk of acute exacerbation or death. No association was detected between weight loss and the risk of ILD progression or the risk of ILD progression or death.

Conclusions

In patients with PPF, lower BMI at baseline and weight loss may be associated with worse outcomes and measures to prevent weight loss may be required.

Trial registration: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02999178.

Plain language summary

Patients with worsening fibrosis (scarring) of the lungs may lose weight. This study suggests that the course of disease may be worse in patients who lose weight. Measures to prevent weight loss may be needed in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with various forms of fibrosing interstitial lung disease (ILD) may develop progressive fibrosing ILD, more recently termed progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), characterized by decline in lung function, increasing fibrosis on radiology, worsening symptoms and quality of life, and high mortality [1]. Decline in lung function in patients with pulmonary fibrosis is associated with mortality [2,3,4].

Many patients with pulmonary fibrosis experience weight loss [5,6,7]. Published data on the association between weight and outcomes in patients with pulmonary fibrosis are conflicting. While some studies have suggested that lower body mass index (BMI) is associated with worse outcomes [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], others have found no significant association [2, 5, 15,16,17]. Weight loss has been associated with worse outcomes in patients with pulmonary fibrosis [5, 7, 9, 10, 13, 18,19,20,21], although among overweight and obese patients, intentional weight loss may improve lung function [22, 23].

The randomized placebo-controlled INBUILD trial of nintedanib was conducted in subjects with progressive fibrosing ILDs other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The results showed that nintedanib slowed decline in lung function, with an adverse event profile characterized mainly by gastrointestinal events [24,25,26]. We analyzed outcomes in the INBUILD trial in subgroups by BMI at baseline and assessed associations between weight change and time-to-event outcomes using a joint modelling approach.

Methods

The design of the INBUILD trial has been described and the protocol is publicly available [24]. Briefly, subjects had an ILD other than IPF with reticular abnormality with traction bronchiectasis (with or without honeycombing) of > 10% extent on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), forced vital capacity (FVC) ≥ 45% predicted and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) ≥ 30– < 80% predicted. Subjects met criteria for ILD progression within the prior 24 months, based on worsening of FVC, abnormalities on HRCT, or symptoms, despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice. Subjects were randomized to receive nintedanib 150 mg bid or placebo, stratified by pattern on HRCT (usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP]-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns [24]). Treatment interruptions (for ≤ 4 weeks for adverse events considered related to trial medication or ≤ 8 weeks for other adverse events) and dose reductions to 100 mg bid were used to manage adverse events. The trial consisted of two parts. Part A comprised 52 weeks of treatment. Part B was a variable period during which subjects continued to receive blinded treatment until all the subjects had completed the trial. The final database lock took place after all subjects had completed the follow-up visit or had entered the open-label extension study, INBUILD-ON (NCT03820726); the data available at this point are referred to as data from the whole trial.

Analyses in subgroups by BMI at baseline

In these post-hoc analyses, we analyzed the rate of decline in FVC (mL/year) over 52 weeks in subgroups by BMI at baseline (< 25, ≥ 25 to < 30, ≥ 30 kg/m2). In the same subgroups, we analyzed two time-to-event endpoints: time to acute exacerbation of ILD (defined in [24]) or death and time to ILD progression (absolute decline in FVC % predicted ≥ 10%) or death. Exploratory interaction p-values were calculated to evaluate potential heterogeneity in the treatment effect of nintedanib versus placebo across the subgroups, a recommended approach for the reporting of subgroup analyses of clinical trials [27, 28]. The analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing. Adverse events are presented descriptively.

Joint modelling

We used joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data. These comprise two sub-models for the respective processes and an association structure to connect them. We assessed the association between change in weight (kg) and three time-to-event endpoints (time to acute exacerbation of ILD or death, time to ILD progression, time to ILD progression or death) over 52 weeks and over the whole trial. In the longitudinal sub-model, a normal mixed effects model of weight was used, with HRCT pattern (UIP-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns) and weight at baseline as predictor variables. Separate mean slopes for subjects in the nintedanib and placebo groups were assumed. Trajectories were modelled by a linear trend with an unstructured variance–covariance matrix assumed. Weight was assessed at baseline, at weeks 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 52 and every 16 weeks thereafter. Only values obtained before an event or censoring timepoint were considered. In the time-to-event sub‑model, a piecewise exponential model with five knots was used to model the baseline hazard. Weight was used as the endogenous time-dependent covariate and treatment as a predictor variable. The sub-model was stratified by HRCT pattern. Subjects were censored once they experienced an event and were not considered at risk of further events.

The shared parameter in each of the joint models was the estimated slope of weight (i.e., the annual rate of change in weight), which assumed that the rate of change in weight affected the risk of an event. Joint models were fitted for each time-to-event endpoint. We present the risk of the first event in terms of 1-unit, 4-unit and 10-unit decreases in weight (kg). The joint model approach was implemented with the SAS macro %JM [29]. Analyses were performed in subjects who had ≥ 1 post-baseline weight measurement and for whom data on the respective time-to-event endpoint were available.

Characteristics of subgroups by weight loss

We present descriptive analyses of the baseline characteristics of subjects with weight loss ≤ 5% and > 5% over the whole trial, based on change in weight from baseline to any visit.

Results

Baseline BMI and outcomes

Among 662 subjects with available data, mean (SD) BMI at baseline was 28.3 (5.3) kg/m2; 28.4%, 36.6% and 35.0% of subjects had a BMI of < 25, ≥ 25 to < 30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively. Compared with subjects with a baseline BMI ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2, a numerically greater proportion of subjects with BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2 were Asian, a greater proportion had autoimmune disease-related ILDs, and a greater proportion had a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT (Additional file 1: Table S1). The mean time since diagnosis of ILD, FVC % predicted and DLco % predicted were similar across the subgroups by baseline BMI (Additional file 1: Table S1).

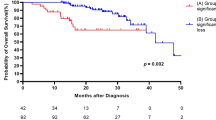

In both the nintedanib and placebo groups, the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks was numerically greater in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 (Fig. 1). The exploratory interaction p-value did not indicate heterogeneity in the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline among the subgroups by baseline BMI (p = 0.83). The median follow-up for the time-to-event endpoints over the whole trial was ≈19 months. In the placebo group, the proportions of subjects who had an acute exacerbation or died, or who had ILD progression or died, was greater in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 or ≥ 25 to < 30 than ≥ 30 kg/m2 (Table 1). The proportions of subjects with these events were similar or lower in the nintedanib than the placebo group across the subgroups by BMI, with no heterogeneity detected among the subgroups (Table 1).

Adverse events and dose adjustments are shown in Table 2. The adverse event profile of nintedanib was similar across subgroups by BMI, with gastrointestinal adverse events the most common events. In the nintedanib group, adverse events of diarrhea and weight decrease were more frequent in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2. Decreased appetite was more frequent in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 in both treatment groups. In the nintedanib group, adverse events leading to dose reduction were more frequent in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2. Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation more frequently in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 than ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 in both treatment groups. The most frequent adverse event leading to discontinuation of nintedanib was diarrhea, which occurred at rates of 4.3, 6.1 and 3.9 events per 100 patient-years in subjects with baseline BMI < 25, ≥ 25 to < 30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively. One subject in the nintedanib group (with baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2) and one subject in the placebo group (with baseline BMI ≥ 25 to < 30 kg/m2) discontinued treatment due to weight loss.

Weight loss and outcomes

Subjects in the nintedanib group had a significantly greater decrease in weight than subjects in the placebo group over 52 weeks (Additional file 1: Table S2) and over the whole trial (Table 3). The baseline characteristics of the subgroups of subjects by weight loss ≤ 5% and > 5% over the whole trial were similar (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Over the whole trial, 19.4% of subjects in the placebo group and 13.9% of subjects in the nintedanib group had an acute exacerbation or died. There was a significant association between weight decrease and time to acute exacerbation or death over 52 weeks (Additional file 1: Table S2) and over the whole trial (Table 3). Based on the estimated slope, a 4 kg weight decrease corresponded to a 1.38-fold (95% CI 1.13, 1.68) increase in the risk of acute exacerbation or death (Fig. 2).

Over the whole trial, 47.7% of subjects in the placebo group and 33.4% of subjects in the nintedanib group experienced ILD progression, and 54.1% of subjects in the placebo group and 39.6% of subjects in the nintedanib group experienced ILD progression or death. No association was detected between weight decrease and the risk of ILD progression or the risk of ILD progression or death (Table 3, Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S2).

Discussion

These analyses of data from the INBUILD trial suggest that there may be associations between baseline BMI or weight loss and clinically relevant outcomes in patients with PPF. The rate of FVC decline, and the risk of ILD progression or death, were numerically greater in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2 than in those with higher BMI. Weight loss during the trial was associated with a significantly increased risk of acute exacerbation or death. As observed in clinical trials in patients with other ILDs [10, 30], nintedanib had a consistent effect on slowing the progression of ILD across the subgroups by baseline BMI.

Our finding that the rate of decline in FVC was greatest in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2 is consistent with observations in subjects with IPF in the INPULSIS trials [10] and other studies in subjects with IPF and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD [13, 14]. In an analysis including data from trials of pirfenidone in patients with IPF, the annualized decline in FVC % predicted was greater in patients with baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2 than BMI ≥ 25 to < 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m2 in the placebo groups, but this was not observed in patients who received pirfenidone [13]. Our finding that the risk of ILD progression or death was numerically greater in subjects with baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2 is consistent with observations from previous studies showing higher mortality in patients with pulmonary fibrosis who have lower BMI [7,8,9, 12]. The reasons why low BMI is associated with worse outcomes in patients with ILDs are not understood, but may be related to loss of muscle mass [31, 32] or to increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor, which have been associated with weight loss in animal studies [33].

Various approaches can be used to investigate associations between a longitudinal measure such as weight and the risk of an outcome. In these analyses, we used a joint modelling approach, as this enables longitudinal markers and time-to-event endpoints to be analyzed simultaneously, overcoming issues of bias and measurement error that occur when repeated measurements and outcomes are analyzed separately, when analyses are based on post-baseline subgroups, or when analyses do not consider longitudinal endpoints as endogenous time-varying factors [34,35,36,37]. This joint modelling also enabled us to evaluate the validity of weight change as a surrogate endpoint for the time-to-event endpoints according to the three levels of surrogacy defined by Taylor and Elston [38]. The significant association between the outcome of weight change and the risk of acute exacerbation or death fulfils Taylor and Elston’s criteria for surrogacy at level two, but further validation is required. While several previous studies have shown that weight loss is associated with a greater risk of mortality in patients with pulmonary fibrosis [5, 7, 9, 10, 13, 18,19,20,21], we are not aware of prior studies suggesting an association between weight loss and acute exacerbations of ILD.

The adverse event profile of nintedanib was generally similar across the subgroups by baseline BMI, but adverse events of diarrhea, decreased appetite and weight decrease, and adverse events leading to dose reduction and treatment discontinuation, were more frequent in subjects who had a baseline BMI < 25 kg/m2 than a higher BMI. In the INPULSIS, SENSCIS and INBUILD trials in subjects with pulmonary fibrosis, the proportion of subjects with adverse events of weight loss over 52 weeks ranged from 9.7 to 12.3% in the nintedanib groups compared to 3.3 to 4.2% in the placebo groups [6, 24, 39]. The reported proportion of patients with IPF treated with nintedanib who experience weight loss in real-world studies is highly variable, likely reflecting differences in methodology and the patient populations studied [40,41,42]. Clinicians should be aware of weight loss as a potential adverse event of nintedanib, particularly in patients with low BMI, and consider nutritional interventions when required. Management of gastrointestinal adverse events associated with nintedanib therapy using symptomatic therapies such as loperamide and dose adjustment is important to minimize their impact and help patients remain on treatment [43, 44].

Strengths of our analyses include the robust collection of data on FVC and weight in the setting of a clinical trial, and the use of a joint modelling approach to assess the associations between weight loss and outcomes [34,35,36,37]. Limitations include that BMI is limited as a measure of nutritional status [45, 46] and that the subgroups with different BMI differed in factors beyond BMI. The lowest BMI subgroup included a greater proportion of subjects with autoimmune disease-related ILDs, which are associated with gastrointestinal complications that may lead to weight loss, and this may have influenced the risk of outcomes across the subgroups. The numbers of subjects with individual ILD diagnoses were too small for these subgroups to be analyzed separately. The number of subjects who were underweight was too small for this group to be analyzed separately. The number of acute exacerbations available for use in the time-to-event analyses was quite small. There were too few deaths for associations between weight change and death alone to be analyzed. Our analyses did not establish cause and effect. These analyses were post-hoc and should be considered exploratory.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these analyses of data from the INBUILD trial suggest that in subjects with PPF, lower BMI at baseline and weight loss may be associated with worse outcomes. Nintedanib had a consistent effect on slowing ILD progression across subgroups by baseline BMI. Physicians should monitor weight in patients with PPF and consider interventions where necessary.

Availability of data and materials

To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results and enable authors to fulfil their role and obligations under the ICMJE criteria, BI grants all external authors access to relevant clinical study data. In adherence with the BI Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data, scientific and medical researchers can request access to clinical study data after publication of the primary manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal, regulatory activities are complete and other criteria are met. Researchers should use https://vivli.org/ to request access to study data and visit https://www.mystudywindow.com/msw/datasharing for further information.

References

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:e18-47.

Paterniti MO, Bi Y, Rekić D, Wang Y, Karimi-Shah BA, Chowdhury BA. Acute exacerbation and decline in forced vital capacity are associated with increased mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1395–402.

Brown KK, Martinez FJ, Walsh SLF, Thannickal VJ, Prasse A, Schlenker-Herceg R, et al. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000085.

Nasser M, Larrieu S, Si-Mohamed S, Ahmad K, Boussel L, Brevet M, et al. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a clinical cohort (the PROGRESS study). Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2002718.

Pugashetti J, Graham J, Boctor N, Mendez C, Foster E, Juarez M, et al. Weight loss as a predictor of mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1801289.

Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, Azuma A, Fischer A, Mayes MD, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2518–28.

Comes A, Wong AW, Fisher JH, Morisset J, Johannson KA, Farrand E, et al. Association of BMI and change in weight with mortality in patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2022;161:1320–9.

Alakhras M, Decker PA, Nadrous HF, Collazo-Clavell M, Ryu JH. Body mass index and mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;131:1448–53.

Kishaba T, Nagano H, Nei Y, Yamashiro S. Body mass index—percent forced vital capacity—respiratory hospitalization: new staging for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:3596–604.

Jouneau S, Crestani B, Thibault R, Lederlin M, Vernhet L, Valenzuela C, et al. Analysis of body mass index, weight loss and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2020;21:312.

Awano N, Jo T, Yasunaga H, Inomata M, Kuse N, Tone M, et al. Body mass index and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00037–2021.

Jouneau S, Rousseau C, Lederlin M, Lescoat A, Kerjouan M, Chauvin P, et al. Malnutrition and decreased food intake at diagnosis are associated with hospitalization and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Clin Nutr. 2022;41:1335–42.

Jouneau S, Crestani B, Thibault R, Lederlin M, Vernhet L, Yang M, et al. Post hoc analysis of clinical outcomes in placebo- and pirfenidone-treated patients with IPF stratified by BMI and weight loss. Respiration. 2022;101:142–54.

Nagy A, Palmer E, Polivka L, Eszes N, Vincze K, Barczi E, et al. Treatment and systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease outcome: the overweight paradox. Biomedicines. 2022;10:434.

Doubková M, Švancara J, Svoboda M, Šterclová M, Bartoš V, Plačková M, et al. EMPIRE Registry, Czech part: impact of demographics, pulmonary function and HRCT on survival and clinical course in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:1526–35.

Snyder L, Neely ML, Hellkamp AS, O’Brien E, de Andrade J, Conoscenti CS, et al. Predictors of death or lung transplant after a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: insights from the IPF-PRO Registry. Respir Res. 2019;20:105.

Brown KK, Inoue Y, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Cottin V, Bonella F, et al. Predictors of mortality in subjects with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respirology. 2022;27:294–300.

Nakatsuka Y, Handa T, Kokosi M, Tanizawa K, Puglisi S, Jacob J, et al. The clinical significance of body weight loss in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Respiration. 2018;96:338–47.

Kulkarni T, Yuan K, Tran-Nguyen TK, Kim YI, de Andrade JA, Luckhardt T, et al. Decrements of body mass index are associated with poor outcomes of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0221905.

Kalininskiy A, Rackow AR, Nagel D, Croft D, McGrane-Minton H, Kottmann RM. Association between weight loss and mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2022;23:377.

Kim TH, Shin YY, Kim HJ, Song MJ, Kim YW, Lim SY, et al. Impact of body weight change on clinical outcomes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis receiving pirfenidone. Sci Rep. 2022;12:17397.

Sekine A, Wasamoto S, Hagiwara E, Yamakawa H, Ikeda S, Okabayashi H, et al. Beneficial impact of weight loss on respiratory function in interstitial lung disease patients with obesity. Respir Investig. 2021;59:247–51.

Schaeffer MR, Kumar DS, Assayag D, Fisher JH, Johannson KA, Khalil N, et al. Association of BMI with pulmonary function, functional capacity, symptoms, and quality of life in ILD. Respir Med. 2022;195: 106792.

Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, Devaraj A, Walsh SLF, Inoue Y, et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1718–27.

Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, Devaraj A, Inoue Y, Richeldi L, et al. Nintedanib in progressive interstitial lung diseases: data from the whole INBUILD trial. Eur Respir J. 2022;59:2004538.

Cottin V, Martinez FJ, Jenkins RG, Belperio JA, Kitamura H, Molina-Molina M, et al. Safety and tolerability of nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: data from the randomized controlled INBUILD trial. Respir Res. 2022;23:85.

Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine–reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2189–94.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the investigation of subgroups in confirmatory clinical trials. 2019. EMA/CHMP/539146/2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-investigation-subgroups-confirmatory-clinical-trials_en.pdf.

Garcia-Hernandez A, Rizopoulos D. %JM: a SAS macro to fit jointly generalized mixed models for longitudinal data and time-to-event responses. J Stat Softw. 2018;84:29.

Jouneau S, Lescoat A, Crestani B, Riemekasten G, Kondoh Y, Smith V et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) by body mass index (BMI) at baseline: subgroup analysis of the SENSCIS trial. Poster presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference. 2020. https://www.usscicomms.com/respiratory/ATS2020/jouneau.

Moon SW, Choi JS, Lee SH, Jung KS, Jung JY, Kang YA, et al. Thoracic skeletal muscle quantification: low muscle mass is related with worse prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Respir Res. 2019;20:35.

Nakano A, Ohkubo H, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, Matsuda T, Yagi M, et al. Early decrease in erector spinae muscle area and future risk of mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2312.

Tracey KJ, Wei H, Manogue KR, Fong Y, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, et al. Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor induces cachexia, anemia, and inflammation. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1211–27.

Arisido MW, Antolini L, Bernasconi DP, Valsecchi MG, Rebora P. Joint model robustness compared with the time-varying covariate Cox model to evaluate the association between a longitudinal marker and a time-to-event endpoint. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:222.

Papageorgiou G, Mauff K, Tomer A, Rizopoulos D. An overview of joint modeling of time-to-event and longitudinal outcomes. Annu Rev Stat Appl. 2019;6:223–40.

Arbeeva L, Nelson AE, Alvarez C, Cleveland RJ, Allen KD, Golightly YM, et al. Application of traditional and emerging methods for the joint analysis of repeated measurements with time-to-event outcomes in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72:615–21.

Chen Y, Postmus D, Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, Simonds AK, et al. Using joint modelling to assess the association between a time-varying biomarker and a survival outcome: an illustrative example in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2003206.

Taylor RS, Elston J. The use of surrogate outcomes in model-based cost-effectiveness analyses: a survey of UK health technology assessment reports. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:iii ix-xi, 1-50.

Corte T, Bonella F, Crestani B, Demedts MG, Richeldi L, Coeck C, et al. Safety, tolerability and appropriate use of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2015;16:116.

Brunnemer E, Wälscher J, Tenenbaum S, Hausmanns J, Schulze K, Seiter M, et al. Real-world experience with nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration. 2018;95:301–9.

Antoniou K, Markopoulou K, Tzouvelekis A, Trachalaki A, Vasarmidi E, Organtzis J, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in a Greek multicentre idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis registry: a retrospective, observational, cohort study. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00172–2019.

Noor S, Nawaz S, Chaudhuri N. Real-world study analysing progression and survival of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with preserved lung function on antifibrotic treatment. Adv Ther. 2021;38:268–77.

Bendstrup E, Wuyts W, Alfaro T, Chaudhuri N, Cornelissen R, Kreuter M, et al. Nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: practical management recommendations for potential adverse events. Respiration. 2019;97:173–84.

Boehringer Ingelheim. Ofev® (nintedanib capsules) prescribing information. 2022. https://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Ofev/ofev.pdf.

Madden AM, Smith S. Body composition and morphological assessment of nutritional status in adults: a review of anthropometric variables. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:7–25.

Jouneau S, Kerjouan M, Rousseau C, Lederlin M, Llamas-Guttierez F, De Latour B, et al. What are the best indicators to assess malnutrition in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients? A cross-sectional study in a referral center. Nutrition. 2019;62:115–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank the INBUILD trial investigators. We thank the patients who participated in the INBUILD trial. The INBUILD trial was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (BI). The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors did not receive payment for development of this manuscript. Writing assistance was provided by Elizabeth Ng and Wendy Morris of FleishmanHillard, London, UK, which was contracted and funded by BI. BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Funding

The INBUILD trial was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, EB, CM and DL contributed to the study design. MK, SJ, TMM, YI, BC contributed to data acquisition. CM conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and to the writing and critical review of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The INBUILD trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonization and was approved by local authorities. The clinical protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Michael Kreuter reports grants, consulting fees and fees for speaking from Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and Roche; and holds leadership or fiduciary roles with Deutsche gesellschaft für Pneumologiex, the European Respiratory Society, and the German Respiratory Society. Elisabeth Bendstrup reports an unrestricted grant from BI; fees for speaking from BI, Chiesi, Roche; support for travel from BI and Roche; and has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for AbbVie and BI. Stéphane Jouneau reports grants from AIRB, BI, LVL, Novartis, Roche; fees for speaking from AIRB, AstraZeneca, BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, LVL, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi; support for travel from BI and Roche; and has participated on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for BI, Novartis, Roche. Toby M. Maher reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blade Therapeutics, BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Galecto, GlaxoSmithKline, IQVIA, Pliant, Respivant, Roche/Genentech, Theravance Biopharma, Veracyte; and fees for speaking from BI and Roche/Genentech. Yoshikazu Inoue reports grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare; fees for lectures from BI, Kyorin, Shionogi, Thermo Fisher; and has served as a consultant or steering committee member for BI, Roche, Savara, Taiho. Corinna Miede is an employee of mainanalytics GmbH, Sulzbach (Taunus), Germany, which was contracted by BI to assist with these analyses. Dirk Lievens is an employee of BI. Bruno Crestani reports grants from BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche; consulting fees from Apellis; fees for speaking from AstraZeneca, BI, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi; and medical writing support from Translate Bio (Sanofi).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Baseline characteristics in subgroups by body mass index (BMI) in the INBUILD trial. Table S2. Association between change in weight (slope) and risk of outcomes over 52 weeks in the INBUILD trial. Table S3. Baseline characteristics of subgroups of subjects by weight loss ≤5% and >5% over the whole INBUILD trial.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kreuter, M., Bendstrup, E., Jouneau, S. et al. Weight loss and outcomes in subjects with progressive pulmonary fibrosis: data from the INBUILD trial. Respir Res 24, 71 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02371-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02371-z