Abstract

Background

The Mesenchymal epithelial transition factor (MET) gene encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase with pleiotropic functions in cancer. MET exon 14 skipping alterations and high-level MET amplification are oncogenic and targetable genetic changes in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has been a major challenge for targeted therapies that impairs their clinical efficacies.

Methods

Eighty-six NSCLC patients were categorized into three cohorts based on the time of detecting MET tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations (cohort 1: at baseline; cohort 2: after MET-TKI treatment; cohort 3: after EGFR-TKI treatment). Baseline and paired TKI treatment samples were analyzed by targeted next-generation sequencing.

Results

MET TKD mutations were highly prevalent in METex14-positive NSCLC patients after MET-TKI treatment, including L1195V, D1228N/H/Y/E, Y1230C/H/N/S, and a double-mutant within codons D1228 and M1229. Missense mutations in MET TKD were also identified at baseline and in post-EGFR-TKI treatment samples, which showed different distribution patterns than those in post-MET-TKI treatment samples. Remarkably, H1094Y and L1195F, absent from MET-TKI-treated patients, were the predominant type of MET TKD mutations in patients after EGFR-TKI treatment. D1228H, which was not found in treatment-naïve patients, also accounted for 14.3% of all MET TKD mutations in EGFR-TKI-treated samples. Two patients with baseline EGFR-sensitizing mutations who acquired MET-V1092I or MET-H1094Y after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment experienced an overall improvement in their clinical symptoms, followed by targeted therapy with MET-TKIs.

Conclusions

MET TKD mutations were identified in both baseline and patients treated with TKIs. MET-H1094Y might play an oncogenic role in NSCLC and may confer acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. Preliminary data indicates that EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who acquired MET-V1092I or MET-H1094Y may benefit from combinatorial therapy with EGFR-TKI and MET-TKI, providing insights into personalized medical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents the major histological subtypes of the disease [1]. A major challenge to improving the benefits of targeted therapies is understanding the molecular mechanisms of acquired resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

Enormous efforts have been made to identify activating mutations, particularly those involved in cancer initiation and drug resistance. Approximately 3% of NSCLC patients harbor MET exon 14 skipping alterations (METex14), resulting in decreased MET turnover and extended oncogenic downstream signaling pathways [2, 3]. The focal genomic amplification of MET (METamp) may also rarely occur as a primary oncogenic driver and is more frequently identified in the context of acquired bypass resistance to EGFR-TKIs [4, 5]. On the other hand, activating mutations in the MET TKD have only been found in 13–20% of type 1 papillary renal cell carcinomas (pRCC), including V1092I, H1094Y/R/L, H1124D, L1195F/V, F1200I, V1188L, Y1220I, D1228H/N, Y1230C/D/H, M1131T, and M1250T, which result in constitutive ligand-independent MET receptor activation and prompt the downstream oncogenic signalling pathways [6].

In NSCLC patients harboring METex14 or METamp, additional MET activating mutations have been clinically documented and preclinically characterized to confer resistance to type I MET inhibitors (i.e., crizotinib, capmatinib and savolitinib) while being sensitive to type II MET inhibitors (i.e., cabozantinib, glesatinib and merestinib) [7,8,9,10]. In particular, D1228N/H and Y1230H/C could mediate resistance to crizotinib in METex14-altered NSCLC by disrupting drug binding. Recent studies have also shown that mutations in L1195 and F1200 residues confer acquired resistance to type II MET-TKIs [11, 12]. However, previous studies were mainly based on case studies, and a comprehensive analysis of the variety of MET TKD mutations that might contribute to acquired resistance to TKIs is required.

In this study, we assessed the targeted sequencing data of 86 NSCLC patients harboring MET TKD mutations. Our study revealed a broad spectrum of MET TKD mutations and provided insights into potential acquired resistance mechanisms to TKIs.

Methods

Patient samples

The extensive database search identified 54,752 NSCLC patients whose tumor specimens and liquid biopsies, including plasma, cardiomyocyte fluid, pleural effusion, and cerebrospinal fluid, were analyzed by targeted NGS between June 2015 and November 2022 at Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc. This study included 138 MET TKD mutation-positive patients whose samples were collected at all participating hospitals. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Geneseeq Medical Laboratory (NSJB-MEC-2023-01). Written consent was obtained from each patient before sample collection. Qualified samples were analyzed by targeted next-generation sequencing using targeted gene panels in a CLIA-certified and CAP-accredited clinical testing laboratory (Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc., Nanjing, China). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples were confirmed by pathologists from the centralized clinical testing center before genetic testing. Liquid biopsies were shipped within 48 h of sample collection to the central testing laboratory for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) extraction and the following tests. Clinical characteristics and treatment history were extracted from medical records.

Targeted next-generation sequencing

DNA extraction was carried out following standard protocols as previously described [13, 14]. Specifically, FFPE samples were de-paraffinized with xylene, followed by genomic DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 56404) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Liquid biopsy samples were centrifuged at 1800 g for 10 min, followed by plasma cfDNA extraction and purification using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 55114). The cfDNA fragment distribution was analyzed on a Bioanalyzer 2100 using the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, 5067-4626). As a normal control, the genomic DNA of white blood cells in sediments was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 69504). The DNA concentration was quantified using the dsDNA HS assay kit on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technology, US) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The NGS library was constructed using the KAPA Hyper Prep kit (KAPA Biosystems) with an optimized manufacturer’s protocol for different sample types. Hybridization-based target enrichment was carried out with GeneseeqPrime™ targeted NGS panel and xGen Lock-down Hybridization and Wash Reagents Kit (Integrated DNA Technologies) [15]. The target-enriched library was then sequenced on HiSeq4000 or HiSeq4000 NGS platforms (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mutation calling

Sequencing data were first demultiplexed and subjected to FASTQ file quality control using Trimmomatic [16]. Qualified data (QC above 15 and without extra N bases) was then subjected to human genome mapping (hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA-mem, v0.7.12; https://github.com/lh3/bwa/tree/master/bwakit). Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK 3.4.0; https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) was employed to perform local realignment around the indels and base quality score recalibration. Picard was used to remove duplicates generated during sample preparation. VarScan2 was applied to detect single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) and insertion/deletion mutations. SNVs were filtered out if the variant allele frequency (VAF) was less than 1% for tumor tissue and 0.3% for liquid biopsy samples. Common SNVs were excluded if they were present in > 1% population in the 1000 Genomes Project or the Exome Aggregation Consortium 65,000 exomes database. The resulting mutation list was further filtered by an in-house list of recurrent artifacts based on a normal pool of whole blood samples. Parallel sequencing of matched white blood cells (control) from each patient was performed to remove sequencing artifacts, germline variants, and clonal hematopoiesis.

Statistical analysis

Two-proportional t-test was used to determine whether the two proportions were different from each other. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare if there were differences between paired observations. A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant for all tests unless indicated otherwise (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.1.3).

Results

Patient overview

A total of 138 NSCLC patients harboring somatic mutations in the MET TKD assessed by targeted NGS were identified from an extensive database search (Fig. 1). After excluding patients without paired treatment samples, 86 NSCLC patients were included in the final analysis and subdivided into three cohorts depending on the time of detecting MET TKD mutations. In particular, MET TKD mutations were identified in 32 treatment-naïve NSCLC patients (cohort 1), 41 MET-TKI-treated patients (cohort 2), and 13 EGFR-TKI-treated patients (cohort 3). Notably, 20 patients in cohort 2 were pretreated with EGFR-TKIs before the onset of MET-TKI treatment. The clinical characteristics of these 86 patients are summarized in Table 1.

Patient cohorts. A total of 138 NSCLC patients harboring MET tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations were included in the study cohort. After excluding patients without paired samples, 86 MET TKD mutation-positive patients were included in the final analysis, which was subdivided into three cohorts: baseline (N = 32), MET-TKI-treated (N = 41), and EGFR-TKI-treated (N = 13)

MET kinase domain mutations were identified in baseline NSCLC patients

Mutations in MET TKD may lead to ligand-independent receptor phosphorylation and activate downstream oncogenic signaling pathways (Additional file 1: Figure S1). However, oncogenic activation through MET TKD mutations has rarely been reported in NSCLC patients. In our study, MET TKD mutations were identified in treatment-naïve patients at an extremely low frequency (0.06%, 32/54,752), including H1094Y/D, L1195F/V, D1228N/Y and Y1230C/H (Fig. 2a). Previously reported oncogenic alterations, including EGFR-sensitizing mutations (25%, 8/32), METamp (6%, 2/32), and METex14 (6%, 2/32), were identified in these baseline patients. Additionally, one patient exhibited an ALK rearrangement, another known oncogenic driver in NSCLC. By comparing the mutational profiles of these patients, we found that 37.5% of baseline MET TKD mutation-positive patients (12/32) harbor at least one known oncogenic driver alteration. Of those 20 mutually exclusive MET TKD mutations found at baseline, H1094Y was detected in 8 patients, followed by L1195F and D1228N in 5 and 3 individuals, respectively (Fig. 2b). L1195V, H1094D, and Y1230H were also identified in baseline NSCLC patients at a relatively low frequency. The variant allele frequency (VAF) of MET TKD mutations in baseline patients was significantly lower than that of EGFR-activating mutations (Additional file 2: Figure S2a).

Somatic gene alterations associated with baseline patients. a The genomic landscape of MET TKD mutation-positive baseline patients (N = 32). Each column represents one patient. The frequency of each gene alteration is listed on the left. b The bar graph demonstrates the number of baseline patients who harbor MET TKD mutations but no previously reported oncogenic driver alterations

Second-site MET mutations as a general resistance mechanism to MET-TKIs

MET TKD mutations, including D1228N/H and those within codons L1195 and F1200, have been clinically documented and preclinically characterized to confer resistance to MET-TKIs in METex14-altered or MET-amplified NSCLC patients [9, 12, 17]. Here, we identified 41 patients who acquired additional MET TKD mutations after MET-TKI treatment. To understand the implication of these mutations in resistance or sensitivity to MET-TKIs, we performed comprehensive genomic profiling using matched samples before and after TKI treatment. Notably, 20 patients were treated with first-line EGFR-TKIs before the onset of MET-TKI treatment due to activating EGFR mutations present at baseline (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, various MET TKD mutations were identified in MET-TKI-treated samples, for example, D1228N (63%), D1228H (42%), Y1230H (20%), Y1230C (15%), D1228Y (12%), and L1195V (10%). It is worth noting that a double-mutant within codons D1228 and M1229 (MET-D1228_M1229delinsFL) was identified in the post-treatment sample of P124. We also observed that V1092I and H1094Y mutations initially identified in samples after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment of patients 24 (P24) and 26 (P26) were no longer detectable after MET-TKI treatment (Fig. 3a). In addition, both the mutational frequency and the copy number of METamp significantly dropped in post-MET-TKI treatment samples (Fig. 3a and Additional file 2: Figure S2b). In contrast, neither the mutational frequency nor the VAF of METex14 showed significant changes in paired samples before and after MET-TKI treatment (Fig. 3a and Additional file 2: Figure S2c). Our findings suggest that acquired MET TKD mutations might confer secondary resistance to MET-TKIs in NSCLC patients, especially in those harboring baseline METex14 alterations.

Genomic alterations identified in NSCLC patients at resistance to TKIs. Frequency of genomic alterations in paired samples of MET-TKI-treated (a) or EGFR-TKI-treated (b) NSCLC patients. Each column represents one patient. The clinical characteristics of patients are shown at the top. The frequency of each gene alteration pre- and post-treatment is listed to the left of the heatmap

MET TKD mutations emerge in NSCLC patients after EGFR-TKI treatment

Although activating mutations, such as L1195V/F and D1228N/H, can cause resistance to MET-TKIs, it is still unclear whether MET TKD mutations confer resistance in NSCLC patients independent of MET inhibition. On the other hand, different mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs have been a matter of intense study in the past few decades. Here, we identified 32 EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who acquired MET TKD mutations post-EGFR-TKI treatment (Fig. 1). Only patients with paired samples before and after treatment were included in the following analysis. Various MET TKD mutations were identified in post-treatment samples, including H1094Y (31%), L1195F (23%), D1228N (23%), D1228H (15%), D1228Y (8%), and L1195V (8%) (Fig. 3b). None of these MET TKD mutations were found in samples pre-EGFR-TKI treatment samples. In addition, we found 4 out of 13 patients harboring concurrent MET TKD mutations with METamp in post-treatment samples. One of the four patients carried an L1195F mutation, one with a D1228H mutation, one with a D1228N mutation, and the fourth with a D1228N/Y double mutation. Meanwhile, we found that MET-H1094Y is unlikely to co-occur with previously assessed acquired mechanisms, including METamp, HER2 amplification [18], BRAF mutation [19], and increased expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL [20]. Although patient 37 carried concurrent KRAS-G12S (VAF 1.59%) and PIK3CA-D1045N (VAF 1.64%), the VAF of MET-1094Y was significantly higher (VAF 9.9%). In addition, PIK3CA-D1045N (VAF 1.64%) identified in the pre-EGFR-TKI treatment sample has not been annotated based on OncoKB (https://www.oncokb.org/). Despite a likely oncogenic role of PIK3CA-C604R in patient 36, this mutation was identified in pre-EGFR-TKI treatment samples of the same patient. While the VAF of EGFR mutations dropped after EGFR-TKI treatment, the opposite was observed in MET TKD mutations (Additional file 2: Figure S2d). These results suggest that H1094Y might confer an acquired resistance mechanism to EGFR-TKIs.

Next, we compared types of MET TKD mutations in baseline and TKI-treated cohorts (Fig. 4a–c). Interestingly, MET-H1094D was only identified in three baseline patients but not in any of the TKI-treated cohorts (Fig. 4a). However, only patient 2 harbored baseline MET-H1094D without any known oncogenic driver mutations (Fig. 2a). At baseline, H1094Y and L1195F were the predominant types and ranked the top two MET TKD mutations after excluding known oncogenic drivers, including EGFR activating mutations, METamp, METex14, and ALK rearrangement (Figs. 2b and 4a). Besides, MET-L1195F mutations, which accounted for 18.2% of all MET TKD mutations in baseline patients, were absent from patients who underwent MET-TKI treatment but were found in EGFR-TKI-treated samples (Fig. 4a–c). In contrast, MET-L1195V was identified in both MET-TKI and EGFR-TKI treatment cohorts at a lower frequency.

Distribution of MET TKD mutations. a–c Distribution of MET TKD mutations in baseline patients (a) and patients who acquired MET mutations post-EGFR-TKI (b) and post-MET-TKI (c) treatment. d The bar graph demonstrates the proportions of patients in three cohorts harboring each type of MET TKD mutation. e Schematic demonstration of potential mechanisms of acquiring MET TKD mutations after EGFR-TKI treatment

Comparing the two TKI-treated groups, we noticed that H1094Y and L1195F mutations, while being the predominant type of MET TKD mutations in the EGFR-TKI group, were absent from the MET-TKI treatment cohort (Fig. 4b–d). However, the high mutational frequency of these mutations at baseline made it difficult to discriminate whether the mutation was induced by clonal expansion of sporadic mutations at baseline or by drug resistance imposed by EGFR inhibitors (Fig. 4e). MET-D1228H mutations, on the other hand, showed enrichment in post-EGFR-TKI treatment samples compared to baseline (P = 0.079), suggesting a potential acquired resistance mechanism to EGFR-TKIs. In contrast, D1228N and Y1230C/H are more likely associated with acquired resistance to MET-TKIs in NSCLC.

MET TKD mutations are sensitive to combinatorial therapy

Precision medicine using EGFR-TKIs on NSCLC patients harboring EGFR-sensitizing mutations has achieved great success. However, disease remission remains a major obstacle due to acquired resistance. Here, we demonstrate that co-targeting both EGFR and MET might be a promising treatment regimen for patients who become resistant to EGFR-TKIs due to acquired MET TKD mutations.

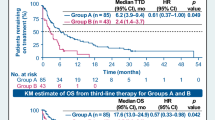

In the MET-TKI treatment cohort, V1092I and H1094Y mutations identified in EGFR-TKI pretreated samples that later vanished in post-MET-TKI treatment samples drew our attention (Fig. 3a). Before MET-TKI treatment, P24 underwent first-line gefitinib and second-line osimertinib therapy after the initial diagnosis of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma (Fig. 5a). Owing to the acquisition of MET-V1092I mutation (VAF 27.7%), the patient was treated with cabozantinib and capmatinib, followed by two cycles of chemotherapy. Targeted sequencing identified MET-D1228N (VAF 2.8%) as well as PI3KCA and BRAF mutations. Treatment was subsequently switched to combinatorial therapy with capmatinib and dacomitinib, and the patient experienced an overall improvement in the clinical symptoms until the symptoms worsened again after three months of treatment. A similar attempt was made in P26, where treating the patient with gefitinib plus crizotinib effectively overcame the MET-H1094Y mutation (Fig. 5b). The patient may benefit from a follow-up treatment with a type II MET-TKI combined with EGFR-TKIs, given that previous studies have demonstrated that the administration of cabozantinib and osimertinib was efficient for rapidly relieving clinical symptoms of patients harboring an acquired mutation of MET-D1228N with good tolerance (Table 2) [21]. The potential for sequential use of combinatorial therapy of osimertinib and cabozantinib has also been demonstrated in a case study where a patient with EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma acquired four MET mutations upon crizotinib treatment [22]. Besides, secondary MET-H1094R/Y conferred by osimertinib resistance can be overcome by simultaneous inhibition of MET and EGFR supported by in vitro evidence [23].

Discussion

In this investigation, we delineate mutational profiles of baseline NSCLC patients and paired samples of those who acquired MET TKD mutations after TKI treatments. Our research reveals a spectrum of MET TKD mutations that might be associated with tumor initiation and drug resistance to TKIs.

In the current era of precision medicine and molecularly targeted therapies, the major task involves finding an optimal treatment choice according to each patient's molecular or genomic characterization of cancer. Evidence has shown that MET alterations, including METex14 mutations and MET gene amplification, are primary oncogenic drivers in NSCLC. Sporadic MET activating mutations, on the other hand, are only found in about 13–20% of pRCC that result in constitutive activation of MET signaling and prompting the downstream oncogenic signaling cascades. The present study identified MET TKD mutations in NSCLC patients before TKI exposure, though at an extremely low frequency. Notably, H1094Y, L1195F/V, and D1228N were among the most frequently found MET TKD mutations not concurrent with other known oncogenic driver alterations. Nevertheless, there is currently insufficient evidence suggesting that these MET TKD mutations play an oncogenic role in NSCLC. Therefore, considerably more studies are needed before drawing a definitive conclusion.

One significant finding of this study was that a broad spectrum of MET TKD mutations was identified in NSCLC patients after MET-TKI and EGFR-TKI treatments. Interestingly, the distribution patterns of these mutations were significantly variable. In METex14-altered or MET-amplified NSCLC patients, the frequency of D1228N/H mutations was significantly higher than that in baseline and EGFR-TKI-treated patients. 22.8% of all MET TKD mutations acquired after MET-TKI treatment were found within codon Y1230. Notably, most of those previously reported MET TKD mutations in pRCC have been identified in our study. Of those commonly found mutations in pRCC and NSCLC, V1092I, H1094Y, L1195V, and Y1230H were recognized as oncogenic mutations, while D1228N and Y1230C were considered likely oncogenic alterations based on OncoKB. Furthermore, novel subtype mutations, including D1228Y/E, D1228_M1229delinsFL, and Y1230N/S, whose biological function in tumorigenesis and development is not known, showed a lower frequency than those previously assessed. Despite these mutations being located in the tyrosine kinase domain of MET, whether they function as activating mutations in NSCLC needs further analysis. On the other hand, although MET-H1094Y and MET-L1195F were found predominantly in patients treated with EGFR-TKI and not in those who underwent MET-TKI treatment, they exhibited high frequency at baseline. Due to the comparable frequency of H1094Y and L1195F in the baseline and EGFR-TKI groups, whether they evolve as subclone mutations or by drug resistance imposed by EGFR-TKIs requires further investigation (Fig. 4e).

Interestingly, MET-H1094Y was the most commonly identified MET TKD mutation at baseline and the most frequently occurring subtype mutation mutually exclusive to known oncogenic drivers (Fig. 2), implying that it could play an oncogenic role in NSCLC. Consistent with this notion, MET-H1094Y is recognized as an oncogenic mutation according to OncoKB. Meanwhile, H1094Y was unlikely to co-occur with other known acquired resistance mechanisms in the EGFR-TKI treatment group (Fig. 3b), suggesting that H1094Y might confer a novel acquired resistance mechanism to EGFR-TKIs. Remarkably, the H1094Y mutation at a VAF of 3.6% identified in patient 26 after first-line EGFR-TKI treatment vanished after second-line MET-TKI treatment, thus, revealing a potential actionable target of MET-TKIs. Moreover, H1094Y might be associated with more effective treatment outcomes of MET-TKIs in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who acquire this mutation after EGFR-TKI resistance.

On the other hand, MET-V1092I was identified at a VAF of 27.7% in patient 24, who underwent first-line EGFR-TKI treatment (Fig. 5a). Since V1092I was undetected at baseline and multiple lines of treatments were applied to the patient after detecting this mutation, whether V1092I is an actionable target of MET-TKI needs further investigation.

There are limitations to our study. Our findings suggest that EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients who acquire MET TKD mutations could benefit from simultaneous EGFR and MET targeting. However, our argument is potentially compromised by the few cases of combinatorial therapy. Although we listed a few studies from others to address the issue of not having enough patients treated with combinatorial treatment, more in vitro and in vivo studies will contribute to further deciphering the relationship between MET TKD mutations and EGFR-TKI resistance. Our extensive database search identified one NSCLC patient harboring a kinase domain deletion mutation of MET after resistance to alectinib, an FDA-approved therapy for treating ALK-positive lung cancer. Although we would like to further access MET TKD mutations in NSCLC patients who underwent ALK-TKI treatment, the current data from this single patient could not help us gather more information or draw a definitive conclusion. Further investigation using larger cohort samples is warranted.

Conclusions

Our study evaluates the clinical significance of MET TKD mutations in NSCLC. We present substantial evidence suggesting that missense mutations in MET TKD exist at baseline and in patients treated with TKIs. Our findings may provide valuable guidance for clinicians in optimizing treatments for EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients harboring MET TKD mutations.

Availability of data and materials

As the study involved human participants, the data cannot be made freely available in the manuscript or a public repository because of ethical restrictions. However, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during this current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MET:

-

Mesenchymal epithelial transition factor

- METex14 :

-

MET Exon 14 skipping alterations

- METamp :

-

MET Amplification

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- TKI:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TKD:

-

Tyrosine kinase domain

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- EGFR:

-

Epithelial growth factor receptor

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- cfDNA:

-

Cell-free DNA

- SNVs:

-

Single-nucleotide variations

- VAF:

-

Variant allele frequency

- pRCC:

-

Papillary renal cell carcinomas

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33.

Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, Chmielecki J, Lu X, Bauer TM, et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(8):850–9.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511(7511):543–50.

Cappuzzo F, Marchetti A, Skokan M, Rossi E, Gajapathy S, Felicioni L, et al. Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1667–74.

Salgia R. MET in lung cancer: biomarker selection based on scientific rationale. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(4):555–65.

Recondo G, Che J, Janne PA, Awad MM. Targeting MET dysregulation in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):922–34.

Ou SI, Young L, Schrock AB, Johnson A, Klempner SJ, Zhu VW, Miller VA, Ali SM. Emergence of preexisting MET Y1230C mutation as a resistance mechanism to crizotinib in NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):137–40.

Heist RS, Sequist LV, Borger D, Gainor JF, Arellano RS, Le LP, et al. Acquired resistance to crizotinib in NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(8):1242–5.

Bahcall M, Sim T, Paweletz CP, Patel JD, Alden RS, Kuang Y, et al. Acquired METD1228V mutation and resistance to MET inhibition in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(12):1334–41.

Tiedt R, Degenkolbe E, Furet P, Appleton BA, Wagner S, Schoepfer J, et al. A drug resistance screen using a selective MET inhibitor reveals a spectrum of mutations that partially overlap with activating mutations found in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5255–64.

Engstrom LD, Aranda R, Lee M, Tovar EA, Essenburg CJ, Madaj Z, et al. Glesatinib exhibits antitumor activity in lung cancer models and patients harboring MET exon 14 mutations and overcomes mutation-mediated resistance to type I MET inhibitors in nonclinical models. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(21):6661–72.

Fujino T, Kobayashi Y, Suda K, Koga T, Nishino M, Ohara S, et al. Sensitivity and resistance of MET exon 14 mutations in lung cancer to eight MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in vitro. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1753–65.

Yang Z, Yang N, Ou Q, Xiang Y, Jiang T, Wu X, et al. Investigating novel resistance mechanisms to third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(13):3097–107.

Shu Y, Wu X, Tong X, Wang X, Chang Z, Mao Y, et al. Circulating tumor DNA mutation profiling by targeted next generation sequencing provides guidance for personalized treatments in multiple cancer types. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):583.

Wang H, Li ZW, Ou Q, Wu X, Nagasaka M, Shao Y, Ou SI, Yang Y. NTRK fusion positive colorectal cancer is a unique subset of CRC with high TMB and microsatellite instability. Cancer Med. 2022;11(13):2541–9.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Recondo G, Bahcall M, Spurr LF, Che J, Ricciuti B, Leonardi GC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of acquired resistance to MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with MET exon 14-mutant NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2615–25.

Takezawa K, Pirazzoli V, Arcila ME, Nebhan CA, Song X, de Stanchina E, et al. HER2 amplification: a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers that lack the second-site EGFRT790M mutation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(10):922–33.

Wu SG, Shih JY. Management of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI-targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):38.

Zhang Z, Lee JC, Lin L, Olivas V, Au V, LaFramboise T, et al. Activation of the AXL kinase causes resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):852–60.

Kuang Y, Wang J, Xu P, Zheng Y, Bai L, Sun X, et al. A rapid and durable response to cabozantinib in an osimertinib-resistant lung cancer patient with MET D1228N mutation: a case report. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(16):1354.

Kang J, Chen HJ, Wang Z, Liu J, Li B, Zhang T, Yang Z, Wu YL, Yang JJ. Osimertinib and cabozantinib combinatorial therapy in an EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma patient with multiple MET secondary-site mutations after resistance to crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(4):e49–53.

Schoenfeld AJ, Chan JM, Kubota D, Sato H, Rizvi H, Daneshbod Y, et al. Tumor analyses reveal squamous transformation and off-target alterations as early resistance mechanisms to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2654–63.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, and the investigators and research staff involved.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation Project (2017A610155). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY and HPY designed this study. BZ performed the data acquisition. YY, HPY, BZ, SW, JHP, XYW and JLZ performed data analysis. YY, HPY, SW, YX and QXO edited the manuscript. HT and ZZ supervised the present study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Geneseeq Medical Laboratory (NSJB-MEC-2023-01). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before sample collection.

Consent for publication

Informed consent form was obtained from each patient.

Competing interests

SW, JHP, XYW, YX, JLZ, JFZ and QXO are employees of Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Mechanism of MET activation. a MET is the receptor of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). The α and β chains encompass the remainder of the extracellular domain, the juxtamembrane domain, and the kinase domain. The intracellular part of MET contains a juxtamembrane region responsible for signal regulation and receptor degradation, a catalytic region with enzyme activity, and a C-terminal region acting as a docking site for adaptor proteins. b The binding of HGF to MET leads to receptor dimerization and phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the kinase domain and autophosphorylation of the C-terminal docking sites, which activates downstream oncogenic signaling pathways, such as RAS/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and STAT3. AKT, protein kinase B; MET, MET proto-oncogene; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RAS, rat sarcoma virus; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins.

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Variant allele frequency and copy number change in three patient cohorts. a Variant allele frequency (VAF) of EGFR and MET TKD mutations in baseline patients. b The copy number of MET amplification before and after MET-TKI treatment. c VAF of MET exon 14 skipping alterations (METex14) before and after MET-TKI treatment. d VAF of EGFR and MET TKD mutations in patients before and after EGFR-TKI treatment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Yang, H., Zhu, B. et al. Mutations in the MET tyrosine kinase domain and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Respir Res 24, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02329-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02329-1