Abstract

Background

Several observational studies have found that idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is often accompanied by elevated circulating C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. However, the causal relationship between them remains to be determined. Therefore, our study aimed to explore the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on IPF risk by the two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods

We analyzed the data from two genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of European ancestry, including circulating CRP levels (204,402 individuals) and IPF (1028 cases and 196,986 controls). We primarily used inverse variance weighted (IVW) to assess the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on IPF risk. MR-Egger regression and MR-PRESSO global test were used to determine pleiotropy. Heterogeneity was examined with Cochran's Q test. The leave-one-out analysis tested the robustness of the results.

Results

We obtained 54 SNPs as instrumental variables (IVs) for circulating CRP levels, and these IVs had no significant horizontal pleiotropy, heterogeneity, or bias. MR analysis revealed a causal effect between elevated circulating CRP levels and increased risk of IPF (ORIVW = 1.446, 95% CI 1.128–1.854, P = 0.004).

Conclusions

The present study indicated that elevated circulating CRP levels could increase the risk of developing IPF in people of European ancestry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is an aggressive, irreversible lung disease marked by scar formation caused by an atypical response to epithelial injury [1]. IPF has become a worldwide public health problem. An epidemiological study found that the incidence of IPF is increasing over time worldwide. The annual incidence in North American and European populations is 3–9/100000, while the incidence in East Asia and South America is lower than that [2]. Furthermore, the prognosis for IPF is poor, with a median survival of only 2.5–3.5 years from diagnosis [3, 4]. Thus, early identifying the underlying risk factors for IPF can help to prevent IPF.

IPF was initially considered an inflammatory disease [5]. Later, investigators found that inflammation is involved in different stages of IPF development due to the activation of the innate and adaptive immune systems [6,7,8]. Environmental influences and genetic risk factors leading to chronic inflammation may be associated with the development of IPF [9]. C-reactive protein (CRP) is often considered a marker of the inflammatory response in the acute phase. Previous studies have found increased CRP concentrations associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, psoriatic arthritis, type 2 diabetes, and cancer [10,11,12,13,14]. And some recent studies have found that CRP is also an important marker of chronic inflammation and may have an etiological role in cancer [10]. Several retrospective studies on IPF indicated that elevated circulating CRP levels are significantly related to poor survival in IPF [15] and may predict mortality during acute exacerbations of IPF [16, 17]. Interestingly, a Mendelian randomization (MR) study found a negative association between CRP and the genetic risk of IPF [18]. In short, the following aspects were considered: (1) there are fewer studies on the causal relationship of circulating CRP levels on the risk of IPF prevalence; (2) some contradictory results have emerged from these studies; (3) observational studies are likely to be affected by potential confounders or reverse causality bias that prevents reliable conclusions from being drawn. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify further the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on IPF.

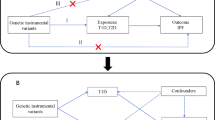

MR analysis is a new epidemiological approach that uses genetic variations as instrumental variables (IVs) to estimate the causal relationship between exposure and outcome [19, 20]. Given that genetic variants are randomly assigned at conception, usually independent of environmental risk factors, and precede disease onset, MR analysis can avoid the effects of reverse causality and unmeasured confounders [20].

In short, the present research intended to assess the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on the risk of developing IPF by a two-sample MR approach using the summary statistics from two large sample genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of European ancestry.

Methods

Data source

To identify genetic loci related to circulating CRP levels, we utilized data from a large-scale GWAS meta-analysis of 88 studies (including 204,402 individuals) [21]. This GWAS meta-analysis revealed 58 genome-wide significant genetic loci for circulating CRP levels, explaining up to 7.0% of the variance in circulating CRP levels [21]. We used GWAS analysis of IPF from FinnGen biobank (freeze 5) as outcome variables, including genotype data of 1028 IPF patients and 196,986 controls [22]. The populations in both of the above GWAS analyses were of European ancestry. And the summary data of both GWAS analyses can be downloaded from the open-access GWAS dataset at https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/ (CRP GWAS ID: ieu-b-35; IPF GWAS ID: finn-b-IPF).

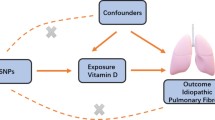

IVs for circulating CRP levels

To use genetic variation to assess the causal association between exposure (circulating CRP levels) and outcome (IPF), it must satisfy three critical assumptions for Ivs [20]: (i) IVs are related to circulating CRP at a genome-wide significant level; (ii) IVs must be independent of any confounders; (iii.) IVs affect IPF only through circulating CRP levels (Fig. 1). Due to the linkage disequilibrium structure in the genome, significant associations between genetic variants and traits were identified at a P = 5 × 10–8 threshold and r2 < 0.001 [23]. Then, we obtained 57 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were significantly related to circulating CRP levels using RStudio 4.1.1 and the package TwoSampleMR, which satisfied the first assumption (Additional file 1). Then, we extracted the data of 56 SNPs out of the above 57 SNPs from IPF GWAS, because rs644234 had no data in IPF GWAS (Additional file 2). In addition, we removed the following SNPs for being palindromic with intermediate allele frequencies: rs10778215, and rs11108056. Finally, we used 54 SNPs as IVs for circulating CRP levels in our study (Additional file 3).

Statistical analysis

A two-sample MR analysis was utilized to examine the genetic relationship between circulating CRP levels and IPF risk. Inverse variance weighted (IVW) [24] was utilized as the major analytic approach, while MR-Egger [25], weighted median [26], weighted mode [27], and simple mode [28] were complementary methods. Then, we performed the sensitivity analyses and indirectly tested the second and third assumptions. Firstly, we tested the horizontal pleiotropy of IVs using the MR-PRESSO global test [29] and MR-Egger regression [25]. Secondly, Cochran's Q test was employed to determine heterogeneity among Ivs [30]. Additionally, we performed the Leave-one-out analysis to determine the undue influence of individual SNPs on the estimation of MR [31]. We performed MR analysis in RStudio 4.1.1 software utilizing the R package TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.6). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

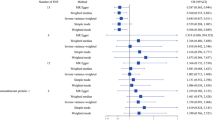

We obtained 54 SNPs as IVs to assess the genetic association of circulating CRP levels with IPF, and the causal effect of each SNP on IPF is shown in the forest plot (Fig. 2). Then, we performed MR analysis using these 54 SNPs, and the results of the IVW method showed a causal effect of the circulating CRP levels on the risk of IPF (ORIVW = 1.446, 95% CI 1.128–1.854, P = 0.004) (Table 1). And MR-Egger (OR = 1.762, 95% CI 1.232–2.521, P = 0.003), weighted median (OR = 1.663, 95% CI 1.170–2.364, P = 0.005) and weighted mode ((OR = 1.660, 95% CI 1.250–2.203, P = 0.001) methods also yielded results consistent with the IVW method (Table 1). As shown in the scatter plot, the risk of developing IPF increases with the increasing circulating CRP levels (Fig. 3).

Subsequently, we performed sensitivity analyses to assess our results. Firstly, Cochran's Q test results suggested no heterogeneity among IVs (PIVW = 0.204, PMR Egger = 0.242, Table 2). The symmetry of the funnel plot also confirmed the absence of heterogeneity (Fig. 4). Secondly, no overall horizontal pleiotropy existed in all IVs, as shown by the results of the MR-PRESSO global test (P = 0.170, Table 2) and MR-Egger regression (P = 0.143, Table 2). This result suggests that IVs are unlikely to affect IPF risk through pathways other than circulating CRP levels. The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis by removing one SNP at a time showed stable results except for rs4420638 (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our study explored the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on the risk of IPF using a two-sample MR analysis. The results showed that elevated circulating CRP levels could lead to an increased risk of IPF. Moreover, sensitivity analysis suggested that our results were robust.

Our results provide one piece of evidence for the previously controversial conclusion. A proteomics study by Niu et al. identified that CRP might be a potential specific biomarker for IPF [32]. And another study retrospectively analyzed clinical data from 86 patients with IPF who underwent lung biopsy and found that elevated CRP concentrations at the time of diagnosis of IPF were significantly associated with poor survival [15]. In addition, since acute exacerbation of IPF is life-threatening, Sakamoto et al. performed a logistic regression analysis of information from 103 cases of acute exacerbation of IPF and found that serum CRP was significantly associated with 3-month mortality [17]. And CRP may be a possible biomarker for predicting mortality in patients with acute exacerbations of IPF [16]. In addition, pirfenidone used for the treatment of IPF may reduce CRP by antagonizing NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) [33,34,35]. These suggested that CRP levels may contribute to the pathogenesis and development of IPF. Although all of these studies found an important marker role for circulating CRP levels in the prognosis of IPF, no study clarified the causal effect of elevated CRP on IPF. And these observational studies are susceptible to potential confounding factors or reverse causality. Interestingly, Si et al. evaluated the association of CRP with hundreds of health outcomes using MR analysis and found a negative association between CRP and IPF risk (OR = 0.28, 95% CI 0.15–0.54) [18]. And our study came to a different conclusion, which seems more realistic.

Previous studies have identified environmental pollutants, dust, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress as potential causes of IPF [36, 37]. In recent years, CRP has been recognized as a systemic marker of chronic inflammation and is an independent risk factor for IPF in many observational studies. Thus, a persistent elevation of circulating CRP levels may represent a state of inflammation, which may increase the risk of IPF. Investigators have found that NLRP3 inflammasome is critical in developing IPF [3]. Pirfenidone, a therapeutic agent for IPF, acts as an antagonist of NLRP3 activation, suggesting that inflammasome may be a potential therapeutic drug target [34]. And a meta-analysis of GWAS indicated that NLRP3 predicted circulating CRP levels [35]. In addition, CRP can stimulate macrophages to produce IL-1 and TNF at sites of inflammation [38], which regulates fibroblast activation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix deposition to promote scar tissue formation [39]. Moreover, CRP exhibits a role in promoting organ fibrosis in different organs. You et al. found that CRP may promote renal fibrosis through a TGF-β/Smad3-dependent mechanism [40], while Zhang et al. found that CRP could activate the TGF-β/Smad and NF-kB signaling pathways under high Ang II conditions to promote cardiac fibrosis [41]. Also, the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway plays an important role in pulmonary fibrosis, and inhibition of TGF-β/Smad3 activation can reduce the extent of pulmonary fibrosis [42,43,44]. Thus, high levels of circulating CRP may increase the risk of IPF by affecting pathways associated with pulmonary fibrosis. These studies provide a possible explanation for the causal effect of circulating CRP levels on the risk of IPF.

Our study has several advantages. Firstly, the present study is the first MR study to assess that elevated circulating CRP levels could increase the risk of IPF and that this association has a causal effect. Secondly, this MR study is based on two large samples of GWAS data from European populations, which provides us with sufficient power to estimate the causal relationship. Thirdly, the MR analysis reveals a long-term effect of genetically determined circulating CRP levels on IPF risk, which is unlikely to be influenced by confounders.

Also, there are some limitations to the study. Firstly, our findings are mainly based on participants of European ancestry and may not apply to populations of other races. Secondly, although we did not find the presence of horizontal pleiotropy, there may be residual bias because the exact function of most of these SNPs is unknown. Thirdly, because our study utilized GWAS summary data and not individual-level data, we were unable to stratify our analysis by other factors such as age and gender. In addition, the circulating CRP levels we studied are genetically controlled, so our results reflected the effect of long-term circulating CRP levels on IPF rather than a short-term response to inflammation.

Conclusions

Overall, our study indicated that elevated circulating CRP levels could increase the risk of developing IPF. This result probably provides new insight into the understanding of the pathogenesis of IPF. However, further pathological and biochemical studies are needed to investigate further the profound relationship of increased risk of IPF by elevated circulating CRP levels.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- MR:

-

Mendelian randomization

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- IVW:

-

Inverse variance weighted

- IV:

-

Instrumental variable

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- NLRP3:

-

NOD-like receptor protein 3

References

Allen RJ, Guillen-Guio B, Oldham JM, Ma SF, Dressen A, Paynton ML, et al. Genome-Wide Association study of susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(5):564–74.

Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(3):795–806.

Moss BJ, Ryter SW, Rosas IO. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2022;17:515–46.

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824.

American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(21):646–64.

Mura M, Belmonte G, Fanti S, Contini P, Pacilli AM, Fasano L, et al. Inflammatory activity is still present in the advanced stages of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2005;10(5):609–14.

Heukels P, Moor CC, von der Thüsen JH, Wijsenbeek MS, Kool M. Inflammation and immunity in IPF pathogenesis and treatment. Respir Med. 2019;147:79–91.

Lu Y, Chen J, Tang K, Wang S, Tian Z, Wang M, et al. Development and validation of the prognostic index based on inflammation-related gene analysis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8: 667459.

Effendi WI, Nagano T. The crucial role of NLRP3 inflammasome in viral infection-associated fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10447.

Heikkilä K, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA. A systematic review of the association between circulating concentrations of C reactive protein and cancer. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(9):824–33.

Brull DJ, Serrano N, Zito F, Jones L, Montgomery HE, Rumley A, et al. Human CRP gene polymorphism influences CRP levels: implications for the prediction and pathogenesis of coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(11):2063–9.

Kallio R, Surcel HM, Bloigu A, Syrjälä H. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and interleukin-8 in the primary diagnosis of infections in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(7):889–94.

Houttekiet C, de Vlam K, Neerinckx B, Lories R. Systematic review of the use of CRP in clinical trials for psoriatic arthritis: a concern for clinical practice? RMD Open. 2022;8(1):e001756.

Scarale MG, Copetti M, Garofolo M, Fontana A, Salvemini L, De Cosmo S, et al. The synergic association of hs-CRP and serum amyloid P component in predicting all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1025–32.

Lee SH, Shim HS, Cho SH, Kim SY, Lee SK, Son JY, et al. Prognostic factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical, physiologic, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2011;28(2):102–12.

Hachisu Y, Murata K, Takei K, Tsuchiya T, Tsurumaki H, Koga Y, et al. Possible serological markers to predict mortality in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Medicina. 2019;55(5):132.

Sakamoto S, Shimizu H, Isshiki T, Nakamura Y, Usui Y, Kurosaki A, et al. New risk scoring system for predicting 3-month mortality after acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1134.

Si S, Li J, Tewara MA, Xue F. Genetically determined chronic low-grade inflammation and hundreds of health outcomes in the UK Biobank and the FinnGen population: a phenome-wide mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 720876.

Thompson J. STEPHEN BURGESS, SIMON G THOMPSON Mendelian randomization: methods for using genetic variants in causal estimation. Boca Raton: CRC Press. Biometrics. 2017;73(1):356.

Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey SG. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27(8):1133–63.

Ligthart S, Vaez A, Võsa U, Stathopoulou MG, de Vries PS, Prins BP, et al. Genome analyses of >200,000 individuals identify 58 loci for chronic inflammation and highlight pathways that link inflammation and complex disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(5):691–706.

Dhindsa RS, Mattsson J, Nag A, Wang Q, Wain LV, Allen R, et al. Identification of a missense variant in SPDL1 associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):392.

Chen Z, Boehnke M, Wen X, Mukherjee B. Revisiting the genome-wide significance threshold for common variant GWAS. G3. 2021;11(2):jkaa056.

Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(7):658–65.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512–25.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304–14.

Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(6):1985–98.

Zhu G, Zhou S, Xu Y, Gao R, Li H, Zhai B, et al. Mendelian randomization study on the causal effects of omega-3 fatty acids on rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(5):1305–12.

Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):693–8.

Hemani G, Bowden J, Davey SG. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(R2):R195-r208.

Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):30–42.

Niu R, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. iTRAQ-based proteomics reveals novel biomarkers for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1): e0170741.

Matsumura T, Tsushima K, Abe M, Suzuki K, Yamagishi K, Matsumura A, et al. The effects of pirfenidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(4):1550–8.

Li Y, Li H, Liu S, Pan P, Su X, Tan H, et al. Pirfenidone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol Immunol. 2018;99:134–44.

Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, Bis JC, Eiriksdottir G, Lu C, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 2011;123(7):731–8.

Selman M, Pardo A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(4):364–72.

Maher TM, Wells AU, Laurent GJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: multiple causes and multiple mechanisms? Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):835–9.

Galve-de Rochemonteix B, Wiktorowicz K, Kushner I, Dayer JM. C-reactive protein increases production of IL-1 alpha, IL-1 beta, and TNF-alpha, and expression of mRNA by human alveolar macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53(4):439–45.

Wick G, Grundtman C, Mayerl C, Wimpissinger TF, Feichtinger J, Zelger B, et al. The immunology of fibrosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:107–35.

You YK, Wu WF, Huang XR, Li HD, Ren YP, Zeng JC, et al. Deletion of Smad3 protects against C-reactive protein-induced renal fibrosis and inflammation in obstructive nephropathy. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(14):3911–22.

Zhang R, Zhang YY, Huang XR, Wu Y, Chung AC, Wu EX, et al. C-reactive protein promotes cardiac fibrosis and inflammation in angiotensin II-induced hypertensive cardiac disease. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):953–60.

Tong J, Wu Z, Wang Y, Hao Q, Liu H, Cao F, et al. Astragaloside IV synergizing with ferulic acid ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis by TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:8845798.

Dai WJ, Qiu J, Sun J, Ma CL, Huang N, Jiang Y, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-9 reduces inflammatory response and fibroblast proliferation in mice with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through the ANO1-mediated TGF-β-Smad3 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(3):2552–65.

O’Donoghue RJ, Knight DA, Richards CD, Prêle CM, Lau HL, Jarnicki AG, et al. Genetic partitioning of interleukin-6 signalling in mice dissociates Stat3 from Smad3-mediated lung fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(9):939–51.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the networks for providing the main data (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/).

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KZ and MC designed the study and drafted the manuscript. KZ, AL, JZ, and CZ performed the data collection and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The 57 SNPs related to circulating CRP levels at a genome-wide significant level.

Additional file 2.

The 56 SNPs in IPF GWAS.

Additional file 3.

IVs for circulating CRP levels.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Li, A., Zhou, J. et al. Genetic association of circulating C-reactive protein levels with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Respir Res 24, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02309-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02309-x