Abstract

Background

Severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is frequently associated with hyperinflammation and hyperferritinemia. The latter is related to increased mortality in COVID-19. Still, it is not clear if iron dysmetabolism is mechanistically linked to COVID-19 pathobiology.

Methods

We herein present data from the ongoing prospective, multicentre, observational CovILD cohort study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04416100), which systematically follows up patients after COVID-19. 109 participants were evaluated 60 days after onset of first COVID-19 symptoms including clinical examination, chest computed tomography and laboratory testing.

Results

We investigated subjects with mild to critical COVID-19, of which the majority received hospital treatment. 60 days after disease onset, 30% of subjects still presented with iron deficiency and 9% had anemia, mostly categorized as anemia of inflammation. Anemic patients had increased levels of inflammation markers such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein and survived a more severe course of COVID-19. Hyperferritinemia was still present in 38% of all individuals and was more frequent in subjects with preceding severe or critical COVID-19. Analysis of the mRNA expression of peripheral blood mononuclear cells demonstrated a correlation of increased ferritin and cytokine mRNA expression in these patients. Finally, persisting hyperferritinemia was significantly associated with severe lung pathologies in computed tomography scans and a decreased performance status as compared to patients without hyperferritinemia.

Discussion

Alterations of iron homeostasis can persist for at least two months after the onset of COVID-19 and are closely associated with non-resolving lung pathologies and impaired physical performance. Determination of serum iron parameters may thus be a easy to access measure to monitor the resolution of COVID-19.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT04416100.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two hallmarks of severe COVID-19 are hyperinflammation, most typically involving a “cytokine storm” with massive interleukin 6 (IL6) expression, and hyperferritinemia [1]. Ferritin is the most relevant cellular iron storage protein and is regulated by both, iron availability and inflammation [2, 3]. Accordingly, IL6 is a key mediator of inflammation-driven iron handling, as it induces the production of hepcidin, the master regulator of iron homeostasis [4]. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux via degradation of the sole cellular iron exporter ferroportin 1 (FPN1), which induces cellular iron retention in macrophages and reduces duodenal iron absorption [5, 6]. Inflammation, therefore, causes alterations of iron homeostasis hallmarked by functional iron deficiency (ID) as reflected by high iron content in reticuloendothelial cells and consequently high serum ferritin levels whereas circulating iron levels are low. Subsequently, inflammation limits this metal’s availability for erythropoiesis, thus causing anemia, termed as anemia of inflammation (AI) [7]. AI is highly prevalent in patients with infections since the underlying immune-mediated iron restriction is considered as an important host defense mechanism to limit microbial proliferation and pathogenicity. Indeed, iron is not only essential for multiple cellular processes for eucaryotes but also for microbes including viruses [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Of importance, over 80% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 presented with inflammation-driven imbalances of iron homeostasis upon admission, which predicted an adverse clinical course [14]. As ferritin also has pro-inflammatory properties, it has been speculated whether or not hyperferritinemia in COVID-19 might contribute to its pathogenesis and severity [15,16,17]. Accordingly, we herein analysed for persisting alterations of iron metabolism in survivors of COVID-19 aiming to evaluate their prevalence and their association with persisting pathologic processes linked to COVID-19.

Methods

Patients and study design

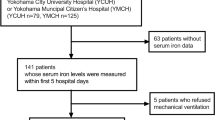

The development of interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (CovILD) study is an ongoing prospective multi-centre observational cohort trial aiming to systematically follow patients after COVID-19 (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04416100). A total of 109 patients, aged 18 years or older, who previously suffered from mild to critical COVID-19 were included. All participants gave informed written consent and the study was approved by the local ethics committee at the Innsbruck Medical University (EK Nr: 1103/2020). The inclusion algorithm is depicted in Additional file 1 Fig. S1. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on typical clinical symptoms and a positive RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 result obtained from a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab. Patients were evaluated 60 days (SD ± 12) after the onset of first COVID-19 symptoms, including clinical examination, medical history assessment, a structured questionnaire to assess typical COVID-19 symptoms, performance evaluation [e.g. six-minute walking test (SMWT)] and the acquisition of blood.

Blood sampling and analysis

Blood samples were taken via routine peripheral vein puncture and analysed by standardized ISO-certified procedures. Additionally, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained via Ficoll–Paque separation (Pharmacia®, Uppsala, Sweden) from whole blood and EDTA or heparin blood was separated via centrifugation at 300×g to collect serum or plasma, respectively, as previously described in detail [18]. PBMC cell pellets were stored at − 80 °C until further use.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR

We extracted total RNA from PBMC cell pellets using a guanidinium-isothiocyanate-phenol-chloroform-based protocol followed by reverse transcription of mRNA into cDNA, as detailed elsewhere [18]. TaqMan-PCR primers and probes or SYBR-Green primers were designed, and real-time PCR quantification was carried out with Bio-Rad® CFX96 qPCR system using SsoAdvanced™ universal probes supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, 152 CA). A list of the primers and probes sequences is depicted in Additional file 1 Table S1.

Definition of anemia, iron deficiency and hyperferritinemia

Iron deficiency (ID) was assessed by ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT), soluble transferrin receptor and the soluble transferrin receptor/log ferritin index (sTFRF index), as previously described [19]. TSAT < 20% in combination with serum ferritin < 100 µg/L was defined as absolute ID, whereas a TSAT < 20% with serum ferritin > 100 µg/L was considered to reflect functional ID [20, 21].

Anemia was diagnosed according to hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations and gender, whereby a Hb below 120 g/L for women and a Hb below 130 g/L for men were used as cut-offs. The sTFRF index, TSAT and ferritin were used to differentiate between absolute and functional iron deficiency in the setting of anemia [21,22,23]. Accordingly, anemia was categorized as iron deficiency anemia (IDA, sTFRF index > 2, TSAT < 20%, serum ferritin < 30 µg/L), anemia of inflammation (AI, TSAT < 20% and serum ferritin > 100 µg/L or serum ferritin 30-100 µg/L and sTFRF index < 1), a combination of both (IDA + AI, TSAT < 20%, serum ferritin 30-100 µg/L, sTFRF index > 2) or unclassifiable anemia (TSAT normal or reduced, serum ferritin > 30 µg/L, sTFRF index 1–2), as previously described [24].

Hyperferritinemia was defined by a serum ferritin > 200 µg/L for women and > 300 µg/L for men, as previously reported [25].

Analysis of lung involvement with computed tomography

60 days after COVID-19 onset, all study participants were evaluated with a low-dose (100 kVp tube potential) computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest. CT was acquired on a 128 slice multidetector CT hardware with a 38.4 × 0.6 mm collimation and spiral pitch factor of 1.1 (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). CT images were evaluated for the presence of ground-glass opacities (GGO), consolidations, bronchiectasis, and reticulations as defined by the glossary of terms of the Fleischner society [26]. The severity of pathological pulmonary findings was graded for every lobe using the following severity score: 0—none, 1—minimal (subtle GGO, very few findings), 2—low (several GGO, subtle reticulation), 3—moderate (multiple GGO, reticulation, small consolidation), 4—marked (extensive GGO, consolidation, reticulation with distortion), and 5—massive (massive findings, parenchymal destructions). The maximum score was 25 (i.e. maximum score 5 per lobe).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with statistical analysis software package (IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0, IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics included tests for homoscedasticity and data distribution (Levene test, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Shapiro–Wilk test and density blot/histogram analysis). According to explorative data analysis, we used the following tests: Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test for group comparisons of continuous data, Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test for binary and categorical data and Spearman rank test to assess correlations. Multiple testing was adjusted by Sidak formula, as appropriate.

Results

Patient characteristics

Subjects were evaluated at a mean of 60 days (SD ± 12 days) after the onset of COVID-19 associated symptoms. The mean age was 58 years (SD ± 14 years) and the majority of participants were male (60%). Detailed characteristics of the cohort including a description of comorbidities are depicted in Table 1. According to the need of medical treatment, disease severity ranged from mild to critical: mild [outpatient treatment, N = 22 (20%)], moderate [inward treatment without respiratory support, N = 34 (31%)], severe [inward treatment with additional oxygen therapy, N = 35 (32%)], whereas 18 patients (17%) had critical disease with the need for mechanical ventilation at an intensive care unit (ICU).

Iron deficiency and anemia

Two months after COVID-19 onset, 30% of all subjects still presented with ID. Of these, 13% had absolute ID and 17% functional ID according to TSAT and serum ferritin based definitions. Anemia was found in ten subjects (9.2%) and was more frequent in males (12%) than females (5%). Disease severity strongly correlated with the prevalence of anemia, as 90% of anemic patients previously had severe to critical COVID-19. Anemic patients primarily suffered from AI (70%) or combined forms of AI and IDA (20%), whereas IDA was only found in one patient. Notably, patients suffering from anemia demonstrated significantly higher IL6 (p = 0.009) and CRP (p = 0.031) concentrations as compared to non-anemic patients.

Post-acute signs of hyperinflammation, coagulopathy and hyperferritinemia

In the post-acute phase of COVID-19, a high proportion of individuals still presented with alterations of circulating biomarkers (Table 2). Most prominently, hyperferritinemia was still present in 38% of all subjects and was far more frequent in male (48%) as compared to female (23%) subjects (p = 0.009). Notably, serum ferritin strongly correlated with serum hepcidin concentrations, but not with markers of cellular iron demand (e.g. soluble transferrin receptor) or markers of inflammation such as CRP or IL6 (Fig. 1). Accordingly, serum hepcidin was positively correlated with TSAT (ρ = 0.328, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with sTFRF index (ρ = − 0.439, p < 0.01), whereas markers of inflammation such as IL6 or CRP were not related to hepcidin levels. Of note, only a minor proportion of individuals presented with persisting mild elevations of inflammatory biomarkers. For instance, IL6 (cut-off > 7 ng/L) was increased in 12% and CRP (cut-off > 0.5 mg/dL) in 16% of the study participants, respectively.

Serum markers of iron homeostasis in post-acute COVID-19 according to disease severity. Correlations of a hepcidin-25, b soluble transferrin receptor (sTFR), c C-reactive protein (CRP) and d interleukin-6 (IL6) with serum ferritin are shown. ρ indicates the correlation coefficient as calculated with Spearman-rank test

Alterations of iron handling and immune effector function in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

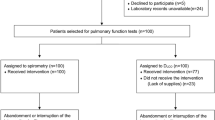

To shed light on the regulation of iron metabolism and its impact on monocyte immune effector functions at the cellular level, we investigated the mRNA expression of key mediators of iron homeostasis as well as cytokine expression in PBMCs. In line with serum hepcidin measurements, we also found increased hepcidin mRNA (HAMP, for hepcidin antimicrobial peptide) expression in PBMCs isolated from subjects who previously had severe to critical COVID-19 as compared to those who suffered from milder disease (Fig. 2). Notably, mRNA levels of genes involved in cellular iron uptake, excretion and distribution, such as transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and ferroportin-1 (FPN1), were not significantly associated with the severity of previous acute COVID-19. In contrast, the immune effector function of PBMCs was related to COVID-19 severity, as mononuclear cells obtained from patients, who suffered from severe to critical disease, demonstrated higher levels of interleukin 10 (IL10, p = 0.044) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF, p = 0.024) mRNA expression as compared to subjects with a milder course of COVID-19 (Fig. 2). Notably, PBMC mRNA expression of hepcidin was not related to monocyte cytokine expression, whereas H-ferritin mRNA concentrations of PBMCs correlated with TNF (ρ = 0.388, p < 0.001), IL10 (ρ = 0,399, p < 0.01) and lipocalin 2 (ρ = 323, p < 0.01) mRNA expression, but not with hepcidin (ρ = 0.609, p < 0.001).

Post-acute mRNA expression of key modulators of iron homeostases and monocyte-derived cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of COVID-19 patients. Relative ΔΔCT mRNA expression as compared to levels in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 are shown. Disease severity was categorized according to the need of medical treatment: mild to moderate, outward treatment or inward treatment without respiratory support; severe to critical, inward treatment with the need for respiratory support (oxygen supply or mechanical ventilation). p values depict significant differences between severity groups as calculated with Mann–Whitney U test, error bars indicate 1 standard error; N = 109. TFR1 transferrin receptor 1, DMT1 divalent metal transporter 1, FPN1 ferroportin-1, IL6 interleukin 6, IL10 interleukin 10, TNF tumor necrosis factor, HAMP hepcidin antimicrobial peptide, n.s. not significant

Association of hyperferritinemia with COVID-19 disease severity

Strikingly, persisting elevations of serum ferritin levels were not only associated with alterations of PBMC cytokine expression but were related to the severity of COVID-19, as patients with a history of more severe disease demonstrated significantly higher serum ferritin concentrations as compared to individuals with milder disease (Fig. 3a). This finding was underlined by CT evaluation 60 days after disease onset, which revealed that in patients with persisting hyperferritinemia pathological CT findings were more frequent and more severe as compared to those with normal ferritin levels (Fig. 3b, c and Fig. 4). In line with this observation, in a subgroup of 23 study participants, who were evaluated with a six-minute walking test (SMWT), hyperferritinemia was associated with a decreased walking distance (Fig. 3d). Notably, in comparison to individuals with normal ferritin levels, patients with hyperferritinemia did not significantly differ in age, gender, frequency of co-morbidities or signs of inflammation, which would otherwise explain the difference in walking performance.

Association of post-acute hyperferritinemia with COVID-19 severity. a Serum concentrations of ferritin according to disease severity (mild: outward treatment; N = 22; moderate: inward treatment without respiratory support, N = 34; sever: inward treatment with additional respiratory support or intensive care unit admission, N = 53). b Frequency of lung pathologies detected with computed tomography (CT) scan 60 days after disease onset in patients with (N = 41) or without (N = 68) hyperferritinemia. c The severity of pathological CT findings according to the evaluation by two independent experts. The severity of lung involvement detected by CT was graded for each lung lobe and a sum score for the total lung was calculated (0–25 points). N = 109. d Six-minute walking distance in patients with (N = 12) or without (N = 11) hyperferritinemia. p values are reported according to the Kruskal–Wallis test (a) or the Mann–Whitney U test (c, d)

Representative CT scans of COVID-19 patients with or without hyperferritinemia. When comparing lung pathologies in CT scans 60 days after COVID-19 onset, patients with persisting hyperferritinemia presented with significantly more severe lung pathologies. A representative CT scan of two individuals without (a) and with (b) hyperferritinemia are shown

Discussion

The rapidly emerging COVID-19 pandemic has overloaded the health care system in many countries worldwide, leaving few capacities to perform prospective trials for this new disease. Still, retrospective analyses have rapidly expanded our knowledge about COVID-19 and resulted in the discovery of a plethora of typical features of the disease [1, 27]. One of these features is the frequent emergence of disturbances of iron homeostasis in COVID-19, most prominently reflected by the high incidence of hyperferritinemia [1, 14, 28]. To date, it is still a matter of debate if disturbances of iron handling are just a reflection of the physiological adaption to the infectious disease or if dysregulated iron homeostasis contributes to COVID-19 pathobiology and disease outcome [15, 16]. The latter assumption is supported by the observation that hyperferritinemia is associated with increased mortality in COVID-19. Mechanistically, it has been suggested that hyperferritinemia and hepcidin dysregulation are related to iron toxicity and may contribute to end-organ damage in COVID-19 [1, 15, 28]. This theory is supported by previous data demonstrating that inflammation induces iron-dependant peroxidation processes resulting in cellular apoptosis, a process which is referred to as ferroptosis [29, 30]. Additionally, cellular iron overload is related to the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which may contribute to tissue damage [31]. Notably, iron dysmetabolism and ferroptosis have also been linked to typical COVID-19 associated symptoms, such as cognitive impairment and anosmia [15, 29]. In line with these observations, we herein describe persistent hyperferritinemia to be more frequent in subjects who suffered from severe or critical COVID-19 as compared to those who had milder disease. Importantly, patients with hyperferritinemia at follow up demonstrated a reduced performance status and persistent pathological finding in pulmonary CT scans.

It has been suggested that the COVID-19 related inflammation may be the main cause of COVID-19 associated iron disorders, as an inflammation-driven dysregulation of iron homeostasis is well established [4, 6, 7]. We herein demonstrate that especially severe COVID-19 causes prolonged alterations of iron handling even at a systemic level, as hyperferritinemia and increased expression of hepcidin are still found in a relevant proportion of patients two months after COVID-19 onset. Notably, our prospective analysis of post-acute COVID-19 associated iron dysmetabolism showed that hyperferritinemia was primarily related to systemic hepcidin expression, whereas no link to persisting inflammation could be established when studying circulating biomarkers. Thus, these data suggest, that in post-acute COVID-19, hepcidin expression is rather driven by iron levels than by persisting inflammatory processes. Of note, our data reveal that dysbalances of iron distribution, which emerge during acute COVID-19, result in prolonged disturbance of iron handling, which per se may impact on the resolution of inflammation and immune effector function of host immune cells. For instance, we previously reported that an acute increase of PBMC iron concentrations induces pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, such as TNF and IL6 production [18]. This mechanism may contribute to uncontrolled cytokine release, as found during the COVID-19 associated “cytokine storm”, as well [1]. In this context, we herein demonstrate that mononuclear cells, which were isolated from subjects following severe COVID-19, had higher mRNA expression levels of cytokines such as TNF and IL10, as compared to individuals with milder disease. Ferritin mRNA regulation at the cellular level was correlated with both cytokine expressions as well as markers of iron homeostasis. This is in line with data that TNF and IL-10 are strong inducers of ferritin expression and suggests that increased ferritin expression may reflect ongoing subclinical inflammation [32, 33]. The persistence of pathological radiological findings in CT and a reduced physical performance, as evident by reduced endurance in the SMWT, of patients with high ferritin levels would support this notion. Accordingly, ferritin may be directly involved in pathologic inflammation and lung injury as ferritin has been reported to act as a pro-inflammatory mediator [17].

In the context of COVID-19 related iron dyshomeostasis, monocytes and macrophages may play a pivotal role. Monocytes and macrophages are crucial mediators of inflammation and inflammation-driven iron sequestration, whereas their immune effector function is altered by iron availability [34]. Thus, these cells may be specifically exposed during COVID-19 and alterations of monocyte/macrophage iron handling may impact on the course of COVID-19 [8, 35].

Finally, we herein demonstrate that disturbances of iron homeostasis can persist for at least two months after the onset of COVID-19 and that prolonged hyperferritinemia is associated with persisting lung pathologies and a reduced physical performance status of COVID-19 patients. This would also suggest that determination of ferritin could be an easy accessible biomarker to monitor the persistence of pathologies following COVID-19. Whereas the herein presented data is observational, thus does not provide evidence for causality, these observations warrant further mechanistic evaluation and may significantly improve the understanding of COVID-19 pathobiology.

Conclusion

In summary, we herein demonstrate that COVID-19 is associated with prolonged alterations of iron homeostasis, which per se are linked to a more severe initial disease but also persisting radiological pathologies in the lung and impaired physical performance of patients. Dysbalanced iron homeostasis is linked to tissue damage and impaired host-immune function, thus it is likely that iron disorders are not only an innocent bystander, but may significantly contribute to the course of COVID-19. Conclusively, further mechanistic evaluations of the role of iron homeostasis in COVID-19 are highly warranted.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data is included in the manuscript or Additional file 1.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Anemia of inflammation

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FPN1:

-

Ferroportin 1

- DMT1:

-

Divalent metal transporter 1

- GGO:

-

Ground-glass opacities

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- IDA:

-

Iron deficiency anemia

- IL6:

-

Interleukin 6

- IL10:

-

Interleukin 10

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- ID:

-

Iron deficiency

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SMWT:

-

Six-minute walking test

- sTFRF index:

-

Soluble transferrin receptor/log ferritin index

- TNF:

-

Tumour necrosis factor

- TFR1:

-

Transferrin receptor 1

- TSAT:

-

Transferrin saturation

References

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. Hlh across speciality Collaboration UK: COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–4.

Arosio P, Ingrassia R, Cavadini P. Ferritins: a family of molecules for iron storage, antioxidation and more. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:589–99.

Kell DB, Pretorius E. Serum ferritin is an important inflammatory disease marker, as it is mainly a leakage product from damaged cells. Metallomics. 2014;6:748–73.

Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK, Ganz T. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1271–6.

Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1434–43.

Theurl I, Aigner E, Theurl M, Nairz M, Seifert M, Schroll A, Sonnweber T, Eberwein L, Witcher DR, Murphy AT, et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis in anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency anemia: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Blood. 2009;113:5277–86.

Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:40–50.

Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis. Science. 2012;338:768–72.

Nairz M, Weiss G. Iron in infection and immunity. Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2020.100864.

Weinberg ED. Iron availability and infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:600–5.

Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, Galy B. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell. 2017;168:344–61.

Soares MP, Weiss G. The iron age of host-microbe interactions. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:1482–500.

Skaar EP, Raffatellu M. Metals in infectious diseases and nutritional immunity. Metallomics. 2015;7:926–8.

Bellmann-Weiler R, Lanser L, Barket R, Rangger L, Schapfl A, Schaber M, Fritsche G, Wöll E, Weiss G. Prevalence and Predictive Value of Anemia and Dysregulated Iron Homeostasis in Patients with COVID-19 Infection. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082429.

Edeas M, Saleh J, Peyssonnaux C. Iron: innocent bystander or vicious culprit in COVID-19 pathogenesis? Int J Infect Dis. 2020;97:303–5.

Cavezzi A, Troiani E, Corrao S. COVID-19: hemoglobin, iron, and hypoxia beyond inflammation. A narrative review. Clin Pract. 2020;10:1271.

Ruddell RG, Hoang-Le D, Barwood JM, Rutherford PS, Piva TJ, Watters DJ, Santambrogio P, Arosio P, Ramm GA. Ferritin functions as a proinflammatory cytokine via iron-independent protein kinase C zeta/nuclear factor kappaB-regulated signaling in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2009;49:887–900.

Sonnweber T, Theurl I, Seifert M, Schroll A, Eder S, Mayer G, Weiss G. Impact of iron treatment on immune effector function and cellular iron status of circulating monocytes in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:977–87.

Sonnweber T, Nairz M, Theurl I, Petzer V, Tymoszuk P, Haschka D, Rieger E, Kaessmann B, Deri M, Watzinger K, et al. The crucial impact of iron deficiency definition for the course of precapillary pulmonary hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0203396.

Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133:30–9.

Pfeiffer CM, Looker AC. Laboratory methodologies for indicators of iron status: strengths, limitations, and analytical challenges. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:1606S-1614S.

Weiss G. Anemia of chronic disorders: new diagnostic tools and new treatment strategies. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:313–20.

Punnonen K, Irjala K, Rajamaki A. Serum transferrin receptor and its ratio to serum ferritin in the diagnosis of iron deficiency. Blood. 1997;89:1052–7.

Sonnweber T, Pizzini A, Tancevski I, Loffler-Ragg J, Weiss G. Anaemia, iron homeostasis and pulmonary hypertension: a review. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:573–85.

Cullis JO, Fitzsimons EJ, Griffiths WJ, Tsochatzis E, Thomas DW, British Society for H. Investigation and management of a raised serum ferritin. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:331–40.

Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62.

Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, Egi M, Lim CM, Divatia JV, Shrestha BR, Arabi YM, Ng J, Gomersall CD, et al. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506–17.

Sun Y, Chen P, Zhai B, Zhang M, Xiang Y, Fang J, Xu S, Gao Y, Chen X, Sui X, Li G. The emerging role of ferroptosis in inflammation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110108.

Ursini F, Maiorino M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: the role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:175–85.

Oexle H, Gnaiger E, Weiss G. Iron-dependent changes in cellular energy metabolism: influence on citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1413:99–107.

Feelders RA, Vreugdenhil G, Eggermont AM, Kuiper-Kramer PA, van Eijk HG, Swaak AJ. Regulation of iron metabolism in the acute-phase response: interferon gamma and tumour necrosis factor alpha induce hypoferraemia, ferritin production and a decrease in circulating transferrin receptors in cancer patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:520–7.

Tilg H, Ulmer H, Kaser A, Weiss G. Role of IL-10 for induction of anemia during inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;169:2204–9.

Nairz M, Theurl I, Swirski FK, Weiss G. “Pumping iron”-how macrophages handle iron at the systemic, microenvironmental, and cellular levels. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:397–418.

Drakesmith H, Prentice A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:541–52.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the commitment of the staff, providers and personnel at the institutions of the Medical University of Innsbruck and Hospital of Zams who contributed to this study.

Funding

We received funding by the Austrian National bank Fund (Project 17271, J.LR.) and the “Verein zur Förderung von Forschung und Weiterbildung in Infektiologie und Immunologie, Innsbruck (G.W.)”. Additionally, I.T. was awarded an Investigator Initiated Study (IIS) grant by Boehringer Ingelheim (IIS 1199-0424).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TS, IT and JLR designed the study. TS, AB, SS, AP, MA, BS, KK, SK DH, VP, MN, BP, AL, CS, RBW, EW, GW, IT and JLR examined patients and collected data. SS, VP, DH and DL collected patients` blood samples. AB, MT, DL and RH isolated PBMCs and performed PCR analysis. AL, CS and GW analysed CT scans. Statistical analysis and preparation of figures were performed by TS. TS, JLR and GW interpreted data. TS and GW wrote the manuscript. The final version was critically reviewed by all authors. TS, IT. JLR and GW had access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants gave informed written consent and the study was approved by the local ethics committee at the Innsbruck Medical University (EK Nr: 1103/2020).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest connected with this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Enrolment of CovILD study participants. Table S1. List of primers and probes for RT-PCR analysis of PBMC mRNA expression patterns.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sonnweber, T., Boehm, A., Sahanic, S. et al. Persisting alterations of iron homeostasis in COVID-19 are associated with non-resolving lung pathologies and poor patients’ performance: a prospective observational cohort study. Respir Res 21, 276 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-01546-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-01546-2