Abstract

Background

Early life impairments leading to lower lung function by adulthood are considered as risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Recently, we compared the lung transcriptomic profile between two mouse strains with extreme total lung capacities to identify plausible pulmonary function determining genes using microarray analysis (GSE80078). Advancement of high-throughput techniques like deep sequencing (eg. RNA-seq) and microarray have resulted in an explosion of genomic data in the online public repositories which however remains under-exploited. Strategic curation of publicly available genomic data with a mouse-human translational approach can effectively implement “3R- Tenet” by reducing screening experiments with animals and performing mechanistic studies using physiologically relevant in vitro model systems. Therefore, we sought to analyze the association of functional variations within human orthologs of mouse lung function candidate genes in a publicly available COPD lung RNA-seq data-set.

Methods

Association of missense single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, deletions, and splice junction variants were analyzed for susceptibility to COPD using RNA-seq data of a Korean population (GSE57148). Expression of the associated genes were studied using the Gene Paint (mouse embryo) and Human Protein Atlas (normal adult human lung) databases. The genes were also assessed for replication of the associations and expression in COPD−/mouse cigarette smoke exposed lung tissues using other datasets.

Results

Significant association (p < 0.05) of variations in 20 genes to higher COPD susceptibility have been detected within the investigated cohort. Association of HJURP, MCRS1 and TLR8 are novel in relation to COPD. The associated ADAM19 and KIT loci have been reported earlier. The remaining 15 genes have also been previously associated to COPD. Differential transcript expression levels of the associated genes in COPD- and/ or mouse emphysematous lung tissues have been detected.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest strategic mouse-human datamining approaches can identify novel COPD candidate genes using existing datasets in the online repositories. The candidates can be further evaluated for mechanistic role through in vitro studies using appropriate primary cells/cell lines. Functional studies can be limited to transgenic animal models of only well supported candidate genes. This approach will lead to a significant reduction of animal experimentation in respiratory research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Progress in the genomics technologies continue to tremendously advance our understanding of chronic lung diseases like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. COPD alone is the 4th leading cause of death globally [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/]. Genetic predisposition is considered to be an important risk factor for COPD susceptibility. This is evident from the fact that only 15–20% of smokers develop COPD [1, 2]. Thus, candidate gene identification has been a major focus for COPD research. This has also lead to the extensive use of inbred mouse strains for screening experiments and also to the development of transgenic mouse models to identify genetic susceptibility, elucidation of molecular patho-mechanisms and toxicity testing in COPD research. However, a spin-off of the popularity of transgenic strains to explore gene-function relationships is the increased animal usage [3]. Another corresponding concern is the large number of animals bred that are genetically unsuited for the experiment. Breeding surplus often counts for 50% of the offspring [3]. Moreover, the relevance of a mouse with a single gene inserted or knocked out for studying human diseases is also questioned. This is mainly because complex traits are multi-gene controlled that do not follow Mendelian pattern of inheritance. Pulmonary function and COPD are classic examples of such phenomenon [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Yet we believe, transgenic models may continue to serve as important resources for studying gene-function relationships particularly in the field of respiratory research. However, the strategy to select candidate genes for using transgenic models to study COPD and other chronic lung diseases is an important issue that warrants attention.

Practice of the “3R tenet”-replacement, reduction and refinement warrants a scientist to adequately evaluate non-animal alternatives prior to performing animal experiments [19, 20]. Strategic genomics data mining using the public repositories can put in practice the “3R-tenet” more effectively by: i) reducing screening experiments with animals, ii) performing mechanistic studies in physiologically relevant alternate in vitro model systems and using advanced technologies like RNAi or CRISPR-Cas9 for understanding gene-function relationships, and iii) performing in vivo functional testing using transgenic animal models limited to well supported candidate genes.

An accelerated decline in lung function is considered to be the earliest indicator for predisposition, onset and COPD severity assessment. We previously identified mouse strains (C3H/HeJ and JF1/MsJ) with extreme total lung capacities [5, 21, 22]. Recently, we performed a large-scale microarray study (GSE80078) to compare the lung transcript expression profiles of C3H/HeJ and JF1/MsJ mice at the completion of: (I) embryonic lung development; (II) bulk alveolar formation and (III) lung growth and maturity [18]. The generated microarray data provides a publicly available resource for performing genetic association studies as well as functional and mechanistic investigations to understand pulmonary function development and chronic lung disease (eg. COPD) susceptibility [18]. Lung developmental pathways are recollected in genetic subroutines during repair and remodeling processes following lung injury. Therefore, it is plausible that an individual with hindered lung development may have an inefficient repair/remodeling process thereby predisposing them to chronic lung diseases like COPD [23,24,25]. A study by Lange et al. [26] showed that forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in early adulthood is important for the genesis of COPD and that accelerated decline in FEV1 is not an obligate feature of COPD. Therefore, in this work, we performed an in-silico study, testing the association of functional variations within human orthologs of mouse lung function candidate genes [18] in a publicly available RNAseq dataset of a COPD cohort [27].

Methods

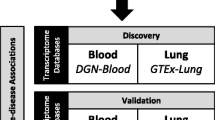

Figure 1 illustrates the overall analysis strategy followed in this study. We focused on the missense single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions and splice site variations for detecting the functional relevance of the associations. Lung transcriptome data (RNA-seq; GSE57148) from a Korean cohort [27] were analyzed to call the variants and to identify the SNPs with significant (p < 0.05) allelic frequency differences between the COPD cases and controls.

Selection of mouse genes

Mouse lung microarray dataset was retrieved (GSE80078) from our recently completed project contrasting C3H/HeJ (large total lung capacity) and JF1/MsJ (small total lung capacity) [18]. Genes exhibiting increased/decreased transcript expression levels by ≥2 fold in the lungs of JF1/MsJ mice compared to C3H/HeJ were selected for performing the association studies. We also included the top 20 genes identified in Kim et al. [27] study and other COPD associated genes by literature survey resulting in a total of 494 genes for screening. Human orthologs of some genes were not found and many were RIKEN or expressed sequence tags. Therefore, the final search list constituted of 355 genes (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Human lung transcriptome data

A publicly available RNA-seq dataset from a Korean cohort consisting of 98 COPD cases and 91 control subjects was selected for the analysis [27]. Based on our search term [(COPD RNA seq human) and “Homo sapiens”] this was the largest available COPD RNA-seq dataset at the Gene expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The raw FASTQ files of paired end reads representing the transcriptome of control and cases were retrieved from the GEO database at the National Centre for Biological Information (NCBI) through accession number GSE57148 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57148) [27].The quality of the raw FASTQ files were analyzed using FASTQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) for the presence of sequencing adapters and low-quality bases (Phred quality score 30). The quality filtered FASTQ files (Paired end) for each sample were then mapped against the Human Reference Genome build hg19 (http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/bigZips/chromFa.tar.gz)usingthe Burrows Wheeler alignment (BWA) tool version 0.7.10 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). The whole genome alignment was performed using ‘BWA-MEM’ algorithm with default parameters [28].

The aligned reads in the Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) format were then sorted using ‘SortSam’ algorithm of Picard tool v.1.118 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/picard/). The Sorted SAM file was converted to binary version of a SAM file (BAM file) using the SAMtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/). The resulting BAM file was then sorted and indexed using SAMtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/) for variant calling. The ‘mpileup’ algorithm of SAM tools was used for calling variants from the sorted BAM file using default parameters. The resulting variant calling file (VCF) containing SNPs was used for the further downstream analysis. The VCF files generated from COPD cases and controls were separately combined using CombineVariants command in Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) v.2.3.9 (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The allele frequency in cases and controls were calculated using VCF tools v.0.1.12a (http://vcftools.sourceforge.net/). The calculated allelic frequencies were considered to compare the differences in SNPs frequencies among the COPD cases and the controls.

Statistics

The relative odds with the “cross-products” ratio was used for calculating statistical significance. Followed by odds ratio estimation, the confidence interval was calculated. Ninety five percent confidence level was considered for the estimation [29]. The odds ratio and the significance of the associations were calculated using a statistical tool MedCalc (https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php). Single variant analysis was performed and the raw p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

In silico assessment of functional consequence of the associated variations on protein biochemistry

The polymorphisms with the significant allelic frequency differences between the COPD cases and controls were further analyzed using the visualization tool ‘Golden Helix GenomeBrowse’ (http://www.goldenhelix.com) to assess the plausible effect of SNPs on protein biochemistry or splicing events. Prosite’ tool of ExPASy [30] was used to analyze the effect of amino acid changes on the functional domains of proteins.

In silico lung expression domain studies of associated genes

Transcript expression of the significantly associated genes were screened in embryonic mouse lungs using the online database “GenePaint” [31]. “The Human Protein Atlas” database [32] was used to identify the immuno-positive lung cells for the significantly associated genes in normal adult human lung.

Lung transcript expression levels of the associated genes in COPD and cigarette smoke exposed mice

The associated 20 genes were scanned for differential transcript expression in several COPD and/ or emphysematous lung tissues (GSE: 29133, 22,148, 1650, 47,460 and 54,837) [33,34,35,36,37] as well as in mouse cigarette smoke exposed lungs (GSE: 8790, 7310, 17,737, and 76,205) [38,39,40] using microarray/RNA-seq datasets from GEO database.

Results

A stringent cut off ratio of ≥2 fold increased/decreased was used to select the mouse lung function developmental genes (GSE80078) for association studies in the RNA-seq dataset of the investigated Korean COPD cohort (GSE57148). Our study identified significant association of 16 non-synonymous SNPs, 4 splice junction variations and 3 insertions involving 20 genes out of the 355 screened genes to higher COPD susceptibility in the investigated cohort (Table 1).

Association of novel and previously reported genes to COPD

The 20 associated genes include: ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 10 (ABCA10); a disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain 19 (ADAM19); basic helix-loop-helix family member e41 (BHLHE41), CD200 molecule (CD200); cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide (CYBB); glycine amidinotransferasec (GATM); guanylate binding protein 1 (GBP1); holliday junction recognition protein (HJURP); KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT); leptin receptor (LEPR); LIM domain 7 (LMO7); LDL receptor related protein 1 (LRP1); microspherule protein 1 (MCRS1); processing of precursor 4, ribonuclease P/MRP subunit (POP4); Patched 1 (PTCH1); sodium channel, voltage-gated, type VII, alpha subunit (SCN7A); schlafen family member 12 like (SLFN12L); toll like receptor 8 (TLR8); tetratricopeptide repeat domain 5 (TTC5) and ventricular zone expressed PH domain homolog 1 (VEPH1).

Our analysis, identified HJURP (rs2286430), MCRS1 (splice junction), and TLR8 (rs3764880) as three novel COPD associated genes (Table 1). The variations (missense SNPs/splice junction variations) on ABCA10 (rs496849), BHLHE41 (rs11048413), CD200 (rs1131199), CYBB (not reported in dbSNP), GATM (rs1288775), GBP1 (rs1048425), LEPR (rs1137101), LMO7 (2 insertions), LRP1 (splice junction), POP4 (splice junction), PTCH1 (splice junction), SCN7A (rs7565062, rs6738031, 1 insertion), SLFN12L (rs2304968), TTC5 (rs3742945), and VEPH1 (rs11918974) are located on genes previously associated to COPD (Table 1). The associated SNPs on ADAM19 (rs1422795) and KIT (rs3822214) have been previously reported in relation to COPD (Table 1).

In silico protein domain and gene/protein expression analysis

In silico protein domain analysis revealed the ADAM19 (rs1422795) variation at the position of Chr5: T-156936364-C resulting in an amino acid exchange of Ser17Gly (polar to non-polar) to be located within the ADAM metalloprotease domain (Additional file 1: Figure S1). None of the other amino acid changes were located within functional domains of the proteins. In silico transcript expression domain analysis using the Gene Paint database (Additional file 1: Table S2) revealed detectable lung expression of Adam19, Cd200, Cybb, Mfleg (HJURP), Kit, Lepr, Lmo7, Lrp1, Mcrs1, Pop4 and Ptch1 in mouse embryo (E14.5; at pseudoglandular stage of lung development). This further attests the role of the mentioned 11 genes in the process of lung development. Impairment in the regulation and functionality of lung developmental genes may result in predisposition to chronic lung diseases like COPD. In silico lung protein expression domain analysis using the Human Protein Atlas revealed detectable immuno-expression of 18 associated genes in macrophages and/or pneumocytes and/or nasopharynx (respiratory epithelial cells) and/or bronchus (respiratory epithelial cells) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Immuno-expression of BHLHE41 and GATM were not detectable in the normal human lung tissue. Detection of expression of the significantly associated COPD susceptibility genes within specific cell types of the normal human lung further supports their specific role in the normal lung physiology. Additional file 1: Figures S1-S4 shows the expression of HJURP, MCRS1 and TLR8 in mouse embryonic lungs and normal adult human lungs. However, human protein atlas does not provide information on the expression of proteins in COPD tissues. Therefore, we investigated the transcript expression levels of the associated genes using available datasets on the lungs of COPD patients and mouse exposed to cigarette smoke.

The associated SNP rs2286430 (C/T) located on HJURP results in an amino acid change of glutamic acid (Glu: acidic, polar and negatively charged) to lysine (Lys: basic, polar and positively charged) in HJURP. Low to medium intensity of HJURP immune positive macrophages, pneumocytes, respiratory epithelial cells have been demonstrated in normal human lung tissue (Additional file 1: Figure S2) (Human Protein Atlas). Hjurp transcripts has been detected in mouse embryonic lungs (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Mcrs1 is expressed in the mouse embryonic lungs (Additional file 1: Figure S3) (Gene Paint). Medium to high intensity immune-positive MCRS1 macrophages, pneumocytes, respiratory epithelial cells have been demonstrated in normal human lung tissue (Additional file 1: Figure S3) (Human Protein Atlas). TLR8 immuno-positive (high intensity) macrophages are reported in normal human lung (Additional file 1: Figure S4). The intensity of TLR8 immuno-positive staining in the respiratory epithelial cells is low (Additional file 1: Figure S4) whereas in pneumocytes and embryonic mouse lung TLR8/Tlr8 was not detectable (Human Protein Atlas; Gene Paint).

Lung transcript expression of the associated genes in other COPD cohorts and mouse studies

We investigated the transcript expression levels of the associated 20 genes in several COPD and/ or emphysematous lung tissue data sets. SLFN12L is the only gene not exhibiting any differential expression in any of the investigated datasets. A summary of the expression pattern of the 20 genes in the investigated COPD lung tissue datasets (GSE: 29133, 22,148, 1650, 47,460 and 54,837) is provided in Additional file 1: Table S3. Mouse cigarette smoke exposure experiments are also another valuable resource to evaluate molecular patho-mechanisms as tobacco smoking is the major risk factor for COPD. We therefore also evaluated the expression of the 20 associated genes in the datasets generated from lungs of mice exposed to cigarette smoke (GSE: 8790, 7310, 17,737, and 76,205) (Additional file 1: Table S4). In case of mouse studies, Gbp1, Mcrs1, Ptch1, Slfn12l, and Ttc5 were the genes not exhibiting altered expression following cigarette smoke exposure. A summary of the expression pattern of the 20 genes in the cigarette smoke exposed mouse lung tissue datasets are provided in the Additional file 1: Table S4. Amongst the 20 candidate COPD genes identified in our study, transcripts of all except GBP1, MCRS1, PTCH1, SLFN12L and TTC5 are differentially expressed in both mouse cigarette smoke exposed lungs and human COPD/emphysematous lungs within the investigated datasets.

Discussion

All datasets investigated in this study originated from the lung samples of human and mouse thereby confirming the tissue specificity (18, 27, 37–40). The dataset GSE57148 from Kim et al. (27) study consisting of 98 COPD patients and 91 control subjects from a Korean population. This was the largest available lung RNA-seq dataset of a COPD cohort in GEO database at the time of study. However, for association studies this is a small sample size. It is important to note that most of the association studies on COPD genetics and genomics of pulmonary function originates from populations with European ancestry. Therefore, the effect of ethnicity on the current findings cannot be ruled out. Additional file 1: Table S5 shows the difference in minor allele frequencies of the associated SNPs between Korean population (http://152.99.75.168/KRGDB/browser/mainBrowser.jsp) and global population (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) justifying the plausible differences in ethnicity.

Apart from lung specific expression of the associated genes, another strength of our study is the focus on missense SNPs (amino acid change), insertions, deletions, and splice junction variations thereby increasing the functional relevance of these associations. A genome-wide analysis of alternative splicing indicated that 40–60% of human genes undergo alternative splicing, often in a tissue specific manner [41,42,43,44]. On the other hand, since we performed the study using RNAseq data, our investigation is limited only to the exonic sequences and therefore could not detect any alterations within the promoter or intronic region. RNAseq data provides information only of a single strand. Thus, our study lacks information on the homozygosity of the identified associations. Availability of the genomic sequence of the same individuals would have overcome this drawback.

We detected association of 20 genes to higher susceptibility for COPD. Our findings on the association of SNPs located on ADAM19 (rs1422795) and KIT (rs3822214) to higher COPD susceptibility replicate the previous findings by other investigators [12, 45,46,47,48]. The rs11048413 SNP on BHLHE41 causing an Ala298Val change have been associated to patient survival in lung adenocarcinoma. The Ala/Val or Val/Val genotype was associated to poor survival rate compared to Ala/Ala genotype [49]. The associated SNP on GATM (rs1288775) has been linked to lung cancer phenotypes with and without emphysema among African-American population but not among white Americans [50]. The SNP rs3764880 on TLR8 has been associated to tuberculosis. The SNP rs3761624 also located on TLR8 which has been associated to allergic rhinites in a Swedish population is in perfect linkage disequibrium with rs3764880 suggesting their complementary relationship [51].

The genes ABCA10, BHLHE41, CD200, CYBB, GATM, GBP1, LEPR, LMO7, LRP1, POP4, PTCH1, SCN7A, SLFN12L, TTC5, and VEPH1 have been previously associated to COPD [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Moreover, we detected altered transcript expression of ABCA10, ADAM19, BHLHE41, CD200, CYBB, GATM, GBP1, HJURP, KIT, LEPR, LMO7, LRP1, MCRS1, POP4, PTCH1, SCN7A, TLR8, TTC5 and VEPH1 in COPD and emphysematous lungs compared to control subjects in various datasets (GSE: 29133, 22,148, 1650, 47,460 and 54,837; Additional file 1: Table S3) [33,34,35,36,37]. In case of mouse lungs exposed to cigarette smoke, altered transcript expression was detected among Abca8a (ABCA10), Adam19, Bhlhe41, Cd200, Cybb, Gatm, Hjurp, Kit, Lepr, Lmo7, Lrp1, Pop4, Scn7a, Tlr8, and Veph1 (GSE: 8790, 7310, 17,737, and 76,205; Additional file 1: Table S4) [38,39,40]. Effect of cigarette smoke exposure on COPD development may act as a confounding factor in the analysis of candidate susceptibility genes in this study. However, considering the concept of recapitulation of developmental pathways as genetic subroutines during lung repair/remodeling processes, altered regulation of the associated genes in both COPD-and cigarette smoke exposed mouse lungs seems to be reasonable. SNPs on ADAM19 (rs2277027), PTCH1 (rs16909898), LRP1 (rs11172113) and hedgehog interacting protein (HHIP; rs12504628, rs1980057) have been associated to FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio in samples of European ancestry [10, 12]. We previously reported decreased lung Hhip transcript levels in a mouse model lacking secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1) with lower total lung capacity and enlarged alveolar size compared to control [8].

Based on the hypothesis on the origin of chronic lung diseases like COPD during the early life events [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70], we could detect three novel (HJURP, MCRS1 and TLR8) COPD candidate genes and replicate the findings in 17 other studies using a mouse-human translational datamining approach. Gene set enrichment analysis [71] of the 20 associated genes identified COPD as one of the top enriched diseases (Additional file 1: Figure S5). HJURP is a centromeric protein (chaperone) that plays a central role in the incorporation and maintenance of histone H3-like variant CENPA at centromeres [72,73,74]. MCRS1 have been implicated in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastasis and growth of lung cancer cells [75,76,77]. TLR8 is also expressed in human monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells and Th1-type immune response cells. Mucus hypersecretion is induced by dual TLR7/8 agonist [78, 79]. Similarly, the murine TLR8 is involved in the activation of innate immune responses [80]. Stimulation of TLR8 causes relaxation of airway smooth muscles thereby preventing broncho-constriction [81]. Association of TLR8 have been also reported for pulmonary tuberculosis [82, 83], asthma and related atopic disorders [84].

Conclusions

Through this study we could demonstrate a candidate gene identification strategy for COPD using mouse-human translational approach using existing genomic datasets in the public repositories. The strategy warrants validation in larger sample size and in multiple cohorts. Cigarette smoke exposure studies in mice are routinely practiced to model emphysema development, a commonly associated COPD phenotype, as it causes increased pulmonary inflammation, protease activity, oxidative stress and apoptosis [85]. However, cigarette smoke exposure in mice does not result in excessive mucus production or mucus cell metaplasia that is characteristic of COPD pathogenesis [85]. It is plausible that the different response to cigarette smoke exposure in human and mouse lungs may be due to their structural differences [85]. The inbred mouse strains also differ significantly in their resistance or susceptibility to emphysema development following cigarette smoke exposure as measured by airspace enlargement [86]. This variable susceptibility among inbred mouse strains to emphysematous change following cigarette smoke exposure may be attributed to their genetic constitution and differences in lung development. Most of the COPD transcriptomic profiling studies have been performed using lung tissue from severely diseased patients requiring lobectomy. On the contrary, COPD pathogenesis occurs over decades. Molecular mechanisms that are active during initial phase of the pathogenesis may be completely different compared to the end stage of the disease. Therefore, creation of a translational profile between mouse and human COPD transcriptomic data is challenging. In this respect, we share similar views as other investigators that it is important to carefully evaluate the common lung-biology and -pathobiology existing between mice and human prior to considering cigarette smoke exposure experiments in mouse models [85]. Single gene driven spontaneous emphysema developing mouse models [47] identified through physiological phenotyping (eg. pulmonary function screening) may serve an important tool to understand molecular patho-mechanism but this requires exhaustive supportive evidence prior to testing the transgenic model. One way of accumulating convincing supportive evidence is explained in the present work. Mechanistic studies to elucidate the role of the novel candidate genes can be performed using appropriate cell lines, primary cells and physiologically relevant in vitro models [87]. This approach would lead to a significant reduction of animal screening experiments in respiratory research.

Abbreviations

- BAM:

-

Binary version of a SAM file

- BWA:

-

Burrows Wheeler Alignment

- GATK:

-

Genome Analysis Tool Kit

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- SAM:

-

Sequence Alignment/Map format

- UCSC:

-

University of California, Santa Cruz

- VCF:

-

Variant Call Format

References

Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Cline MG, Lebowitz MD. Quantitative relationships between cigarette smoking and Ventilatory function 1, 2. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;115(2):195–205.

Coultas DB, Hanis CL, Howard CA, Skipper BJ, Samet JM. Heritability of ventilatory function in smoking and nonsmoking New Mexico Hispanics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(4):770–5.

Hendriksen CF. Towards eliminating the use of animals for regulatory required vaccine quality control. ALTEX. 2006;23(3):187–90.

Reinhard C, Meyer B, Fuchs H, Stoeger T, Eder G, Rüschendorf F, et al. Genomewide linkage analysis identifies novel genetic loci for lung function in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171(8):880–8.

Ganguly K, Stoeger T, Wesselkamper SC, Reinhard C, Sartor MA, Medvedovic M, et al. Candidate genes controlling pulmonary function in mice: transcript profiling and predicted protein structure. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31(3):410–21.

Ganguly K, Depner M, Fattman C, Bein K, Oury TD, Wesselkamper SC, et al. Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular (SOD3) variants and lung function. Physiol Genomics. 2009;37(3):260–7.

Ganguly K, Upadhyay S, Irmler M, Takenaka S, Pukelsheim K, Beckers J, et al. Impaired resolution of inflammatory response in the lungs of JF1/Msf mice following carbon nanoparticle instillation. Respir Res. 2011;12(1):94.

Ganguly K, Martin TM, Concel VJ, Upadhyay S, Bein K, Brant KA, et al. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 is a determinant of lung function development in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51(5):637–51.

Beauchemin KJ, Wells JM, Kho AT, Philip VM, Kamir D, Kohane IS, et al. Temporal dynamics of the developing lung transcriptome in three common inbred strains of laboratory mice reveals multiple stages of postnatal alveolar development. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2318.

Repapi E, Sayers I, Wain LV, Burton PR, Johnson T, Obeidat M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five loci associated with lung function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):36–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.501.

Yao TC, Du G, Han L, Sun Y, Hu D, Yang JJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of lung function phenotypes in a founder population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(1):248–55.e1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.018.

Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):45–52.

Soler Artigas M, Wain LV, Repapi E, Obeidat M, Sayers I, Burton PR, et al. Effect of five genetic variants associated with lung function on the risk of chronic obstructive lung disease, and their joint effects on lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(7):786–95. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201102-0192OC.

Tang W, Kowgier M, Loth DW, Soler Artigas M, Joubert BR, Hodge E, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association studies and meta-analyses of longitudinal change in adult lung function. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e100776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100776.

Loth DW, Soler Artigas M, Gharib SA, Wain LV, Franceschini N, Koch B, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies six new loci associated with forced vital capacity. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):669–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3011.

Soler Artigas M, Loth DW, Wain LV, Gharib SA, Obeidat M, Tang W, et al. Genome-wide associationand large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1082–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.941.

Obeidat ME, Hao K, Bossé Y, Nickle DC, Nie Y, Postma DS, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying variations in lung function: a systems genetics analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(10):782–95.

George L, Mitra A, Thimraj TA, Irmler M, Vishweswaraiah S, Lunding L, et al. Transcriptomic analysis comparing mouse strains with extreme total lung capacities identifies novel candidate genes for pulmonary function. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):152.

Russell WMS, Burch RL, Hume CW. The principles of humane experimental technique. London: Methuen; 1959.

Fenwick N, Griffin G, Gauthier C. The welfare of animals used in science: how the "three Rs" ethic guides improvements. Can Vet J. 2009;50(5):523–30.

Reinhard C, Eder G, Fuchs H, Ziesenis A, Heyder J, Schulz H. Inbred strain variation in lung function. Mamm Genome. 2002;13(8):429–37.

Reinhard C, Meyer B, Fuchs H, Stoeger T, Eder G, Rüschendorf F, et al. Genomewide linkage analysis identifies novel genetic loci for lung function in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):880–8.

Stocks J, Sonnappa S. Early life influences on the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2013;7(3):161–73.

Hagood JS, Ambalavanan N. Systems biology of lung development and regeneration: current knowledge and recommendations for future research. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2013;5:125–33.

Stabler CT, Morrisey EE. Developmental pathways in lung regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:677–85.

Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):111–22.

Kim WJ, Lim JH, Lee JS, Lee SD, Kim JH, Oh YM. Comprehensive analysis of transcriptome sequencing data in the lung tissues of COPD subjects. Int J Genom. 2015;2015:206937. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/206937.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324.

Parshall MB. Unpacking the 2 × 2 table. Heart Lung. 2013;42(3):221–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.01.006.

de Castro E, Sigrist CJ, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, et al. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W362-5.

Visel A, Thaller C, Eichele G. GenePaint.org: an atlas of gene expression patterns in the mouse embryo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D552–6.

Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260419.

Fujino N, Ota C, Takahashi T, Suzuki T, et al. Gene expression profiles of alveolar type II cells of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001553. Print 2012. PubMed PMID: 23117565.

Singh D, Fox SM, Tal-Singer R, Plumb J, et al. Induced sputum genes associated with spirometric and radiological disease severity in COPD ex-smokers. Thorax. 2011;66(6):489–95.

Spira A, Beane J, Pinto-Plata V, Kadar A, et al. Gene expression profiling of human lung tissue from smokers with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(6):601–10.

Peng X, Moore M, Mathur A, Zhou Y, et al. Plexin C1 deficiency permits synaptotagmin 7-mediated macrophage migration and enhances mammalian lung fibrosis. FASEB J. 2016;30(12):4056–70.

Singh D, Fox SM, Tal-Singer R, Bates S, et al. Altered gene expression in blood and sputum in COPD frequent exacerbators in the ECLIPSE cohort. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107381.

Rangasamy T, Misra V, Zhen L, Tankersley CG, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in a/J mice is associated with pulmonary oxidative stress, apoptosis of lung cells, and global alterations in gene expression. Am J Phys Lung Cell Mol Phys. 2009;296(6):L888–900.

McGrath-Morrow S, Rangasamy T, Cho C, Sussan T, et al. Impaired lung homeostasis in neonatal mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38(4):393–400.

Miller MA, Danhorn T, Cruickshank-Quinn CI, Leach SM, et al. Gene and metabolite time-course response to cigarette smoking in mouse lung and plasma. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178281.

Krawczak M, Reiss J, Cooper DN. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992;90(1–2):41–54.

Modrek B, Lee C. A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat Genet. 2002;30(1):13–9.

Stamm S, Ben-Ari S, Rafalska I, Tang Y, Zhang Z, Toiber D, et al. Function of alternative splicing. Gene. 2005;344:1–20.

Lalonde E, Ha KC, Wang Z, Bemmo A, Kleinman CL, Kwan T, et al. RNA sequencing reveals the role of splicing polymorphisms in regulating human gene expression. Genome Res. 2011;21(4):545–54. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.111211.110.

Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Litonjua AA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lomas DA, et al. COPD gene and Eclipse investigators. The association of genome-wide significant spirometric loci with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(6):1147–53. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2011-0055OC.

London SJ, Gao W, Gharib SA, Hancock DB, Wilk JB, House JS, et al. ADAM19 and HTR4 variants and pulmonary function: cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium targeted sequencing study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7(3):350–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000066.

Lindsey JY, Ganguly K, Brass DM, Li Z, Potts EN, Degan S, et al. C-kit is essential for alveolar maintenance and protection from emphysema-like disease in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(12):1644–52. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201007-1157OC.

Yuan YP, Shi YH, Gu WC. Analysis of protein-protein interaction network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(4):8862–9. https://doi.org/10.4238/2014.

Falvella FS, Spinola M, Manenti G, Conti B, Pastorino U, Skaug V, et al. Common polymorphisms in D12S1034 flanking genes RASSF8 and BHLHB3 are not associated with lung adenocarcinoma risk. Lung Cancer. 2007;56(1):1–7.

Lusk CM, Wenzlaff AS, Dyson G, Purrington KS, Watza D, Land S, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals genetic variability among lung cancer cases subphenotyped for emphysema. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37(2):139–44.

Nilsson D, Andiappan AK, Halldén C, De Yun W, Säll T, Tim CF, Cardell LO. Toll-like receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with allergic rhinitis: a case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:66.

Berg T, Hegelund Myrbäck T, Olsson M, Seidegård J, Werkström V, Zhou XH, et al. Gene expression analysis of membrane transporters and drug-metabolizing enzymes in the lung of healthy and COPD subjects. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2014;2(4):e00054. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.54.

Sakthivel P, Breithaupt A, Gereke M, Copland DA, Schulz C, Gruber AD, et al. Soluble CD200 correlates with Interleukin-6 levels in sera of COPD patients: potential implication of the CD200/CD200R Axis in the disease course. Lung. 2017;195(1):59–68.

Faner R, Gonzalez N, Cruz T, Kalko SG, Agustí A. Systemic inflammatory response to smoking in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence of a gender effect. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97491.

Lusk CM, Wenzlaff AS, Dyson G, Purrington KS, Watza D, Land S, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals genetic variability among lung cancer cases subphenotyped for emphysema. Carcinogenesis. 2015;37(2):139–44.

Siafakas NM, Antoniou KM, Tzortzaki EG. Role of angiogenesis and vascular remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(4):453–62.

Shaykhiev R, Krause A, Salit J, Strulovici-Barel Y, Harvey BG, O'Connor TP, et al. Smoking-dependent reprogramming of alveolar macrophage polarization: implication for pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2009;183(4):2867–83. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.0900473.

Hansel NN, Gao L, Rafaels NM, Mathias RA, Neptune ER, Tankersley C, et al. Leptin receptor polymorphisms and lung function decline in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(1):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00120408.

van den Borst B, Souren NY, Loos RJ, Paulussen AD, Derom C, Schols AM, et al. Genetics of maximally attained lung function: a role for leptin? Respir Med. 2012;106(2):235–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.001.

Soler Artigas M, Loth DW, Wain LV, Gharib SA, Obeidat M, Tang W, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1082–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.941.

Berndt A, Leme AS, Shapiro SD. Emerging genetics of COPD. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(11):1144–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/emmm.201100627.

Wujak L, Chen Y, Preissner KT, Wygrecka M. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 is a novel activator of β1 integrin-dependent fibroblast adhesion, spreading and migration. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(Suppl 58):P749.

Seys LJ, Verhamme FM, Dupont LL, Desauter E, Duerr J, Agircan AS, et al. Airway surface dehydration aggravates cigarette smoke-induced hallmarks of COPD in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129897.

Van Durme YM, Eijgelsheim M, Joos GF, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Brusselle GG, Stricker BH. Hedgehog-interacting protein is a COPD susceptibility gene: the Rotterdam study. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(1):89–95. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00129509. Epub 2009 Dec 8. PubMed PMID: 19996190

Ortega VE, Kumar R. The effect of ancestry and genetic variation on lung function predictions: what is "normal" lung function in diverse human populations? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(4):16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0516-2.

Lee MK, Hong Y, Kim SY, London SJ, Kim WJ. DNA methylation and smoking in Korean adults: epigenome-wide association study. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-016-0266-6.

Almusrati WK. Glucocorticoid resistance in COPD patients and lung cancer (Doctoral dissertation, Environment and life science). 2016. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/37538.

Siedlinski M, Cho MH, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lomas DA, Anderson W, Kong X, Rennard SI, Beaty TH, Hokanson JE, Crapo JD. Genome-wide association study of smoking behaviours in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200598.

Krauss-Etschmann S, Bush A, Bellusci S, Brusselle GG, Dahlén SE, Dehmel S, et al. Of flies, mice and men: a systematic approach to understanding the early life origins of chronic lung disease. Thorax. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201902.

Stocks J, Hislop A, Sonnappa S. Early lung development: lifelong effect on respiratory health and disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(9):728–42.

Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Duan Q, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, Clark NR, Ma'ayan A. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128.

Foltz DR, Jansen LE, Bailey AO, Yates JR, Bassett EA, Wood S, et al. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell. 2009;137(3):472–84.

Dunleavy EM, Roche D, Tagami H, Lacoste N, Ray-Gallet D, Nakamura Y, et al. HJURP is a cell-cycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell. 2009;137(3):485–97.

Kato T, Sato N, Hayama S, Yamabuki T, Ito T, Miyamoto M, et al. Activation of Holliday junction recognizing protein involved in the chromosomal stability and immortality of cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8544–53.

Liu MX, Zhou KC, Cao Y. MCRS1 overexpression, which is specifically inhibited by miR-129*, promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2014;13(1):245.

Liu M, Zhou K, Huang Y, Cao Y. The candidate oncogene (MCRS1) promotes the growth of human lung cancer cells via the miR–155–Rb1 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34(1):121.

Bartis D, Mise N, Mahida RY, Eickelberg O, Thickett DR. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition in lung development and disease: does it exist and is it important? Thorax. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204608.

Damera G, Panettieri RA Jr. Does airway smooth muscle express an inflammatory phenotype in asthma? Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(1):68–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01165.x.

Wang D, Precopio M, Lan T, Yu D, Tang JX, Kandimalla ER, et al. Antitumor activity and immune response induction of a dual agonist of toll-like receptors 7 and 8. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(6):1788–97. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1198.

Li T, He X, Jia H, Chen G, Zeng S, Fang Y, et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of murine toll-like receptor 8. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(2):1119–26. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4668.

Drake MG, Scott GD, Proskocil BJ, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB, Kaufman EH. Toll-like receptor 7 rapidly relaxes human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):664–72. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201303-0442OC.

Dalgic N, Tekin D, Kayaalti Z, Cakir E, Soylemezoglu T, Sancar M. Relationship between toll-like receptor 8 gene polymorphisms and pediatric pulmonary tuberculosis. Dis Markers. 2011;31(1):33–8. https://doi.org/10.3233/DMA-2011-0800. PubMed PMID: 21846947; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3826908

Davila S, Hibberd ML, Hari Dass R, Wong HE, Sahiratmadja E, Bonnard C, Alisjahbana B, Szeszko JS, Balabanova Y, Drobniewski F, van Crevel R, van de Vosse E, Nejentsev S, Ottenhoff TH, Seielstad M. Genetic association and expression studies indicate a role of toll-like receptor 8 in pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(10):e1000218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000218.

Møller-Larsen S, Nyegaard M, Haagerup A, Vestbo J, Kruse TA, Børglum AD. Association analysis identifies TLR7 and TLR8 as novel risk genes in asthma and related disorders. Thorax. 2008;63(12):1064–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2007.094128.

Vandivier RW, Ghosh M. Understanding the relevance of the mouse cigarette smoke model of COPD: peering through the smoke. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57(1):3–4. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2017-0110ED.

Radder JE, Gregory AD, Leme AS, Cho MH, Chu Y, Kelly NJ, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Beaty TH, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, Zhang Y, Berndt A, Shapiro SD. Variable susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in 34 inbred strains of mice implicates Abi3bp in emphysema susceptibility. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57(3):367–75. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2016-0220OC.

Upadhyay S, Palmberg L. Air liquid Interface: relevant in vitro models for investigating air pollutant-induced pulmonary toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfy053.

Funding

This study was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India: BT/PR12987/INF/22/205/2015, and VINNOVA (2016–01951) (K.G.).

Availability of data and materials

Microarray data used is available at the Genome Expression Omnibus (GEO) database at National Center for Biotechnology Information NCBI (GSE80078) [18]. Human RNAseq data is also available at NCBI (GSE57148) [27].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG, SV, LG and PN designed and conceived the project; PN, SV, and LG performed the computational experiments and analyzed the data; KG, SV and LG wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human participants: human data or human tissue: not applicable.

Mice: Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable; Microarray data and RNAseq data from public repository have been used.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. List of the genes screened for association to higher Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) susceptibility. Table S2. Summary of the transcript (Gene Paint; mouse embryo) and protein (Human Protein Atlas) expression domains of the significantly associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) genes. Table S3. Analysis of lung transcript expression of the associated 20 genes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and/ or emphysematous lung tissues using available datasets [GSE: 29133, 22,148, 1650, 47,460 and 54,837] in Genome Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. ↓: Decreased ↑: Increased ✓: significantly altered. Table S4. Analysis of l transcript expression of the associated 20 genes in mouse cigarette smoke exposed lungs using available datasets [GSE: 8790, 7310, 17,737, and 6205] in Genome Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. ↓: Decreased ↑: Increased ✓: significantly altered. Table S5. The difference in minor allele frequencies of the associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between Korean population and global population indicates the influence of ethnicity on the findings. The Korean population data was accessed from the KoreanDB: http://152.99.75.168/KRGDB/menuPages/firstInfo.jsp and http://152.99.75.168/KRGDB/browser/mainBrowser.jsp Global SNP data(dbSNP database): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/. Figure S1. Analysis of protein domain and functional sites in the “A Disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain 19” (ADAM19). Figure S2. Transcript (Gene Paint; mouse embryo) and protein expression (Human Protein atlas; normal lung) domain of holliday junction recognition protein (HJURP). Figure S3. Transcript (Gene Paint; mouse embryo) and protein expression (Human Protein atlas; normal lung) domain of microspherule protein 1 (MCRS1). Figure S4. Protein expression (Human Protein atlas; normal lung) domain of toll like receptor 8 (TLR8). Figure S5. Gene-set enrichment analysis for the associated 20 genes for (A) cellular component enrichment (B) biological process enrichment (C) molecular function enrichment (D) diseases enrichment using Enrichr interactive enrichment analysis tool [71]. (PDF 1296 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Vishweswaraiah, S., George, L., Purushothaman, N. et al. A candidate gene identification strategy utilizing mouse to human big-data mining: “3R-tenet” in COPD genetic research. Respir Res 19, 92 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0795-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0795-y