Abstract

Background

Pleural effusions present a diagnostic challenge. Approximately 20% are associated with cancer and some 50% require invasive procedures to perform diagnosis. Determination of tumour markers may help to identify patients with malignant effusions. Two strategies are used to obtain high specificity in the differential diagnosis of malignant pleural effusions: a) high cut-off, and b) fluid/serum (F/S) ratio and low cut-off. The aim of this study is to compare these two strategies and to establish whether the identification of possible false positives using benign biomarkers – ADA, CRP and % of polymorphonuclear cells – improves diagnostic accuracy.

Methods

We studied 402 pleural effusions, 122 of them malignant. Benign biomarkers were determined in pleural fluid, and CEA, CA72-4, CA19-9 and CA15-3 in pleural fluid and serum.

Results

Establishing a cut-off value for each TM for a specificity of 100%, a joint sensitivity of 66.5% was obtained. With the F/S strategy and low cut-off points, sensitivity was 77% and specificity 98.2%, Subclassifying cases with negative benign biomarkers, both strategies achieved a specificity of 100%; sensitivity was 69.9% for single determination and 80.6% for F/S ratio.

Conclusions

The best interpretation of TM in the differential diagnosis of malignant pleural effusions is obtained using the F/S ratio in the group with negative benign biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pleural effusions present a diagnostic challenge. Between 15 and 30% are associated with cancer and between 40 and 60% require invasive procedures to perform diagnosis [1,2,3]. The clinical utility of tumour markers (TM) in the differential diagnosis of malignancy in pleural effusions is controversial. In the literature a wide range of sensitivity, specificity and cut-off values have been reported [4,5,6], but it is very difficult to establish criteria that can be used in routine practice. Several studies have used a single determination of tumour markers in pleural effusions, but establishing cut-off points is problematic – among other reasons, because different types of immunoassay kits obtain different concentrations in the same samples [7].

Equally, the cut-off points may differ according to the aim of the study [8,9,10].

Another cause of discrepancy between studies is found in the types of benign diseases recorded. It has been reported that tuberculosis, complicated parapneumonic effusions and empyemas may have high concentrations of tumour markers in pleural fluid, related to the inflammation of the mesothelial cells or nearby tissues [11,12,13,14].. Adenosine deaminase (ADA), C Reactive Protein (CRP) and granulocyte count are all used in the differential diagnosis of tuberculous effusions, parapneumonic effusions and empyema [15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Paramalignant effusions represent another source of discrepancy. Patients with these effusions have cancer, but no neoplastic cells are present in the pleural mesothelium; however, patients may have high concentrations of tumour markers in serum. So, tumour markers may be found in effusion fluids alongside other macromolecules such as albumin, and they may be present in high concentrations in the pleura. Other benign diseases with high serum concentrations of tumour markers may present similar behaviour [22].

Therefore, in order to obtain high specificity using only values of TM in effusion, high cut-off points have usually been used. However,, our group described a strategy based on two criteria including a low cut-off and the fluid/serum (F/S) ratio [23]. Analysing three types of effusion and using a combination of CEA, CA15-3 and CA19-9, we obtained a sensitivity of 76.2% and a specificity of 97%. Likewise, subclassifying these effusions according to their ADA, CRP and % of polymorphonuclear cells (%PN) value, patients with negative ADA, CRP and %PN obtained a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 100% with the F/S ratio >1.2.

The aim of the present study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of these two strategies: a cut-off point for each tumour marker in fluid effusion to obtain maximum specificity, and the F/S ratio in pleural effusions in order to validate previous results. We also intended to establish whether the classification in groups according ADA, CRP and % of polymorphonuclear cells, might help to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Methods

From January 2008 to December 2012, fluid and serum samples were collected from consecutive patients of all medical specialties at our center who presented pleural effusions. Diagnostic procedures were performed by assessors who were blind to the study data.

The reference method used was pathological confirmation of cancer in serous effusions or definitive diagnosis assessed during the three months following the determination of TM. Serous effusions were defined as malignant when the presence of neoplastic cells was detected by cytology, biopsy or autopsy. Paramalignant effusions were defined as effusions in which no neoplastic cells were detected by any of the methods described above in patients diagnosed with cancer.

In order to identify benign effusions we determined the following test in fluid and/or serum: protein, albumin, Nt-ProBNP, LDH, microbiological cultures, and if necessary antinuclear antibodies, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, rheumatoid factor, thyrotropin, and serological tests for viruses, bacteria and fungi.

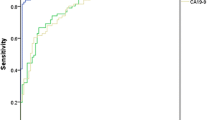

Effusion fluid and serum samples were collected and analysed on the same day. CEA, CA15-3, CA 72–4 and CA19-9 were determined using an electrochemiluminescence method on a Cobas 601 analyser (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain). The analytical variation expressed as the between-assay coefficient of variation was 5.0, 3.0, 4.2 and 4.5% for CEA, CA15-3, CA72-4 and CA 19–9 at concentrations of 5 μg/L, 32 KU/L, 8.3 KU/L and 29 KU/L respectively. In the first approach, using a single determination in pleural fluid, we established the cut-off for each TM at a specificity of 100% with the ROC curve. For the second approach, simultaneous determinations were performed in fluid and serum; effusions were considered malignant when at least one of these TM CEA, CA15-3, CA72-4 or CA19-9 in fluids were above the URL and the F/S ratio was above 1.2. TM in serum were determined only in patients presenting TM values in pleural fluid above the upper reference limit (URL) in serum (5 μg/L for CEA; 30KU/L for CA15-3; 6.9KU/L for CA72-4, and 37KU/L for CA19-9).

The criteria used to suggest that an effusion might be a false positive (i.e., empyema, complicated parapneumonic or tuberculous) were %PN > 90, CRP > 50 mg/L or ADA >45U/L [20]. The use of the biomarkers ADA, CRP and %PN identified two groups of effusions: group A, effusions with all biomarkers below the cut-off point, and group B, effusions with at least one positive biomarker. ADA (EC3.5.4.4) (ITC Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) and CRP (Tina-quant CRP latex, Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) were determined in an LX-20 autoanalyser (Beckman Coulter Madrid, Spain). Leukocyte count was performed in a Neubauer chamber and May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain. The analytical variation expressed as the between-assay coefficient of variation was 7.4% for ADA and 2.3% for CRP at concentrations of 10.3 U/L and 76.6 mg/L respectively.

Statistical analysis

ROC analysis was used to establish cut-off points for each TM at a specificity of 100%.

Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive values (NPV) and positive predictive values (PPV) were calculated for each TM and for the combination of TM. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows v.20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and Stata® v.10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

A total of 402 consecutive pleural effusions were included, from 148 women and 254 men with ages ranging from 15 to 93 years (mean 72.2; SD 14.2). Out of the effusions assessed, 280 (69.7%) had a benign aetiology and 122 (30.3%) were malignant (Table 1). The effusions were classified in two groups: group A, those with ADA < 45 U/L, CRP < 50 mg/L and %PN < 90%, and group B, those with at least one of the following: ADA >45 U/L, CRP > 50 mg/L and %PN > 90% (Table 1). Figures. 1a and b show the flow charts of participants in this study.

The cut-offs with a specificity of 100% obtained with a single determination in pleural effusions were 80 KU/L, 60 μg/L, 209 KU/L and 21 KU/L for CA15-3, CEA, CA19-9 and CA72-4 respectively. For the whole group (Fig. 1a) the sensitivity for all effusions with at least one tumour marker above the cut-off was 63.9%, compared with 51.4% in the group of patients with negative cytology (Tables 2 and 3). The alternative approach (at least one TM above the URL measured in pleural effusion and F/S ratio >1.2) had a sensitivity of 77%, a specificity of 98.2%, an NPV of 90.7% and a PPV of 94.7%; the corresponding results for patients with negative cytology were 71.4, 98.2, 93.2 and 90.9%. When subclassifying according to ADA, CRP, and %PN (Fig. 1b) in group A specificity reached 100% and sensitivities were 69.9% for the whole group and 54.5% in patients with negative cytology using a single cut-off. Using the F/S ratio strategy, specificity reached 100% and sensitivities were 80.6% for the whole group and 72.7% in patients with negative cytology (Tables 2 and 3). In group B, sensitivity fell by more than 6% in both whole group and negative cytology for the two strategies. In addition, using the F/S ratio the specificity fell by more than 6% both in the whole group and in the patients with negative cytology.

Table 4 shows the sensitivity for each strategy according to tumour type and for all tumour markers. The combination of tumour markers allowed detection of more than 80% of the lung, breast, ovarian or bladder cancers and cancers of unknown primary. Other tumours such as lymphoma were not detected.

Discussion

In our study we evaluated two strategies for assessing tumour markers in pleural effusions. Our results for both strategies were concordant with those of previous publications. With a single determination in pleural fluid, we obtained a joint sensitivity for TM of 63.9% using high cut-off points (60 μg/L for CEA, 80 KU/Lfor CA15-3, 209 KU/Lfor CA19-9 and 21 KU/L for CA72-4). Other studies have shown discriminant values ranging from 40 to 50 μg/L for CEA, 53 to 75 KU/L for CA15-3 and 8.9 to 16 KU/L for CA 72–4 [8, 12, 13, 24], obtaining maximum specificities with sensitivities of between 25 and 45% for each marker individually and between 50 and 70% for the combination. These results are similar to ours. Furthermore, the combined use of URL to detect TM in pleural effusions and the F/S ratio > 1:2 achieved a sensitivity of 77% of and a specificity of 98.2% for the whole group; values similar to those described to those in previous studies conducted by our group with patients presenting pleural, peritoneal and pericardial effusions [23].

The main problem with the use high cut-offs for TM in the differential diagnosis of pleural effusion is the wide range of cut-offs, sensitivities and specificities that we find in the literature, indicating that the discriminant values may depend on the cohort. On this point, considerable differences may be found depending on the type of immunoassay used. Assessing CA15-3, Slev et al. [7]. found concentrations ranging from 8.4 to 16.8 KU/L for Lyphochek low, and from 19.2 to 44.2 KU/L for Lyphochek high. With CYFRA21-1,, Porcel et al. [8] sought high specificity (100%) and obtained a sensitivity of 25% with a cut-off point of 175 μg/L with positive likelihood ratio (LHR+) >9999 and negative likelihood ratio (LHR-) of 0.75, Cynowska et al. [9] sought high sensitivity (90.9%) and obtained a specificity of 7.7% with a cut-off point of 3.3 μg/L with LHR+ of 0.98 and LHR- of 1.18; finally, Korczynski et al. [10], seeking high diagnostic accuracy, obtained a sensitivity of 41.7% and a specificity of 92.1% with a cut-off point of 74.7 μg/L LHR+ of 5.28 and LHR- of 0.63. Likewise, cut-off points ranging between 6.5 and 275 μg/L have been proposed for CEA in order to obtain maximum specificity [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Comparing the two strategies, the simultaneous determination of TM in serum and effusions and the F/S ratio > 1.2 achieves a 10% higher sensitivity than the single determination, but a lower specificity (98%). In order to improve these data, we assessed the two strategies in group A alone (that is, cases with a low risk of false positives following benign inflammatory processes). In this group, simultaneous determination reached 100% specificity and maintained ranges of sensitivity. Thus, in patients with negative cytology (58% of malignant effusions), sensitivity rose from 54.5 to 72.7%.

Using the F/S ratio and classifying according to ADA, CRP or %PN, we obtained the same specificity in two different studies, and so it seems that this strategy does not vary over time or between series in effusions with negative ADA, CRP and %PN. This strategy uses as a reference the serum concentration measured with the same immunoassay. It avoids some of the problems associated with the single determination of TM, for example the increase in TM concentrations in fluid in patients with high TM concentrations in serum.

Classifying patients on the basis of biomarkers such as ADA, CRP and %PN also allows identification of some benign effusions with high concentrations of TM, thus increasing diagnostic accuracy. The group without suspicion of false positives has higher sensitivity and specificity using either strategy, while in the group of potential false positives sensitivity is much lower with both. In the patients in group B (with at least positive one of the following: ADA, CRP and % of polymorphonuclear cells) included all false positives due to benign release of TM in fluid in both groups, we also found a decrease in sensitivity because this group included fewer malignant effusions and because more than 40% of tumours were non-epithelial, compared with a rate of 18% in group A.

The data suggest that the best diagnostic accuracy (with very high likelihood ratios) is achieved by using the F/S ratio in group A, that is, patients without suspicion of false positives due to benign diseases. We propose an algorithm for the use of tumour markers in pleural effusions (Fig. 2). The strategy would be to determine tumour markers in fluid effusion; if all are below low cut-off levels (CEA 5 μg/L; CA15-3 30 KU/L; CA19-9 37 KU/L and CA72-4 6.9 KU/L) then the probability of malignant effusion is low. If the fluid effusion concentration is above this cut-off point, ADA, CRP and %PN should be assessed; if at least one is positive, benign disease should be considered. In spite of this, if clinically there is a high suspicion of malignant effusion high cut-offs should be used (60 μg/L, 80 KU/L, 209 KU/L and 21 KU/L for CEA, CA15-3, CA19-9 and CA72-4 respectively). Finally, if ADA, CRP and %PN are negative serum concentrations of TM should be determined and the F/S ratio calculated; if it is above 1.2 there is a very high probability of malignant effusion (LHR+ >999). This is especially important in patients with negative cytology. The use of these criteria can detect three out of four patients with malignant effusion and negative cytology.

Patients with a previous diagnosis of neoplasia and the appearance of pleural effusion with negative cytology and positivity for tumour markers can be taken as presenting disease progression; similarly, the presence of pleural and effusion and positive tumour markers but negative cytology in newly diagnosed localized tumours may indicate pleural metastasis. These and other practical considerations raised by these data should be addressed in a case by case team discussion.

The main limitation of this study is the fact that it was performed at a single centre. Multicentre studies are needed to validate the results and to determine whether they are also applicable to other measurement systems.

Conclusions

To obtain the maximum diagnostic yield from the measurement of tumour markers in pleural effusions, we support simultaneous determination of markers in fluid and serum with a low cut-off point in patients in whom no increases in TM due to benign disease are suspected (i.e., with ADA, CRP and PN% below the discriminant values). In patients in whom increases in TM due to benign disease are suspected, the strategy of a single determination in fluid may offer better diagnostic accuracy.

Abbreviations

- %PN:

-

Percent of polynuclear cells

- ADA:

-

Adenosine deaminase

- CA15-3:

-

Cancer antigen 15–3

- CA19-9:

-

Cancer antigen 19–9

- CA72-4:

-

Cancer antigen 72–4

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CRP:

-

“c” reactive protein

- CUP:

-

Cancer of unknown primary

- CYFRA 21–1:

-

Cytokeratin fragment 19

- F/S:

-

Fluid/serum ratio

- LHR-:

-

Likelihood ratio negative

- LHR+:

-

Likelihood ratio positive

- PSPC:

-

Papillary serous of peritoneum carcinoma

- TM:

-

Tumor markers

- URL:

-

Upper reference limit

References

Light RW. Clinical practice. Pleural effusion. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1971–7.

Porcel JM, Esquerda A, Vives M, Bielsa S. Etiology of pleural effusions: analysis of more than 3,000 consecutive thoracenteses. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:161–5.

Alemán C, Sanchez L, Alegre J, Ruiz E, Vázquez A, Soriano T, Sarrapio J, Teixidor J, Andreu J, Felip E, Armadans L, Fernández De Sevilla T. Differentiating between malignant and idiopathic pleural effusions: the value of diagnostic procedures. QJM. 2007;100:351–9.

Gu P, Huang G, Chen Y, Zhu C, Yuan JS, Sheng S. Diagnostic utility of pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA 21–1 in patients with pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2007;21:398–405.

Shi HZ, Liang QL, Jiang J, Qin XJ, Yang HB. Diagnostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in malignant pleural effusion: a meta-analysis. Respirology. 2008;13:518–27.

Liang QL, Shi HZ, Qin XJ, Liang XD, Jiang J, Yang HB. Diagnostic accuracy of tumour markers for malignant pleural effusion: a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2008;63:35–41.

Slev PR, Rawlins ML, Roberts WL. Performance characteristics of seven automated CA 15–3 assays. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:752–7.

Porcel JM, Vives M, Esquerda A, Salud A, Pérez B, Rodríguez-Panadero F. Use of a panel of tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 15–3, and cytokeratin 19 fragments) in pleural fluid for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant effusions. Chest. 2004;126:1757–63.

Cynowska B, Słomiński JM, Goszka LW, Andrzejewski W, Wolf H. Value of determination of lung cancer marker Cyfra 21–1 for differentiation of pleural fluid – preliminary report. Med Sci Monit. 1998;4:934–7.

Korczynski P, Krenke R, Safianowska A, Gorska K, Abou Chaz MB, Maskey-Warzechowska M, Kondracka A, Nasilowski J, Chazan R. Diagnostic utility of pleural fluid and serum markers in differentiation between malignant and non-malignant pleural effusions. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:128–33.

Garcia-Pachon E, Padilla-Navas I, Dosda MD, Miralles-Llopis A. Elevated level of carcinoembryonic antigen in nonmalignant pleural effusions. Chest. 1997;111:643–7.

Ferrer J, Villarino MA, Encabo G, Felip E, Bermejo B, Vilà S, Orriols R. Diagnostic utility of CYFRA 21–1, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 125, neuron specific enolase, and squamous cell antigen level determinations in the serum and pleural fluid of patients with pleural effusions. Cancer. 1999;86:1488–95.

Villena V, López-Encuentra A, Echave-Sustaeta J, Martín-Escribano P, Ortuño-de-Solo B, Estenoz-Alfaro J. Diagnostic value of CA 549 in pleural fluid. Comparison with CEA, CA 15.3 and CA 72.4. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:289–94.

Ryu JS, Lee HJ, Cho JH, Han HS, Lee HL. The implication of elevated carcinoembryonic antigen level in pleural fluid of patients with non-malignant pleural effusion. Respirology. 2003;8:487–91.

Segura RM, Pascual C, Ocaña I, Martínez-Vázquez JM, Ribera E, Ruiz I, Pelegrí MD. Adenosine deaminase in body fluids: a useful diagnostic tool in tuberculosis. Clin Biochem. 1989;22:141–8.

Castaño Vidriales JL, Amores Antequera C. Use of pleural fluid C-reactive protein in laboratory diagnosis of pleural effusions. Eur J Med. 1992;1:201–7.

Garcia-Pachon E, Soler MJ, Padilla-Navas I, Romero V, Shum C. C-reactive protein in lymphocytic pleural effusions: a diagnostic aid in tuberculous pleuritis. Respiration. 2005;72:486–9.

Chierakul N, Kanitsap A, Chaiprasert A, Viriyataveekul R. A simple C-reactive protein measurement for the differentiation between tuberculous and malignant pleural effusion. Respirology. 2004;9:66–9.

Chen SC, Chen W, Hsu WH, Yu YH, Shih CM. Role of pleural fluid C-reactive protein concentration in discriminating uncomplicated parapneumonic pleural effusions from complicated parapneumonic effusion and empyema. Lung. 2006;184:141–5.

Garcia-Pachon E, Llorca I. Diagnostic value of C-reactive protein in exudative pleural effusions. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13:246–9.

Tahhan M, Ugurman F, Gozu A, Akkalyoncu B, Samurkasoglu B. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in comparison to adenosine deaminase in tuberculous pleuritis. Respiration. 2003;70:270–4.

Trapé J, Filella X, Alsina-Donadeu M, Juan-Pereira L, Bosch-Ferrer A, Rigo-Bonnin R. Oncology section of the Catalan Association of Clinical Laboratory Science Increased plasma concentrations of tumour markers in the absence of neoplasia. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1605–20.

Trapé J, Molina R, Sant F, Montesinos J, Arnau A, Franquesa J, Blavia R, Martín E, Marquilles E, Perich D, Pérez C, Roca JM, Doménech M, López J, Badal JM. Diagnostic accuracy of tumour markers in serous effusions: a validation study. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:1661–8.

Villena V, López-Encuentra A, Echave-Sustaeta J, Martín-Escribano P, Ortuño-de-Solo B, Estenoz-Alfaro J. Diagnostic value of CA 72–4, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 15–3, and CA 19–9 assay in pleural fluid. A study of 207 patients. Cancer. 1996;78:736–40.

Gaspar MJ, De Miguel J, García Díaz JD, Díez M. Clinical utility of a combination of tumour markers in the diagnosis of malignant pleural effusions. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2947–52.

Trapé J, Molina R, Sant F. Clinical evaluation of the simultaneous determination of tumour markers in fluid and serum and their ratio in the differential diagnosis of serous effusions. Tumour Biol. 2004;25:276–81.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank Michael Maudsley for help with the translation and edition of the manuscript.

Funding

For this study no funding was made.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: JT, RM; Analysis and interpretation: JT, AA, JM, JF, MS, MG, GG, JB, JL; Histological examination FS, JMB; Acquisition data: OB, DP, CP, EM, SR, EE, RP, MB, MD, JA, SC, JO, Critical revisions: All authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Ethical committee of the Unió Catalana d’Hospital (n° 12/05).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Trapé, J., Sant, F., Franquesa, J. et al. Evaluation of two strategies for the interpretation of tumour markers in pleural effusions. Respir Res 18, 103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0582-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0582-1