Abstract

Background

Steroid resistant (SR) asthma is characterized by persistent airway inflammation that fails to resolve despite treatment with high doses of corticosteroids. Furthermore, SR patient airways show increased numbers neutrophils, which are less responsive to glucocorticoid. The present study seeks to determine whether dexamethasone (DEX) has different effect on neutrophils from steroid sensitive (SS) asthmatics compared to SR asthmatics.

Methods

Adults with asthma (n = 38) were classified as SR or SS based on changes in lung FEV1% following a one-month inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment. Blood samples were collected from all patients during their first visit of the study. Neutrophils isolated from the blood were cultured with dexamethasone and/or atopic asthmatic serum for 18 h. The mRNA expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1), a glucocorticoid transactivation target, and glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 (GLCCI1), an early marker of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis whose expression was associated with the response to inhaled glucocorticoids in asthma , was determined by real-time PCR, and ELISA was used to assess the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 levels in the supernatant. Constitutive neutrophil apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry.

Results

DEX significantly induced MKP-1 expression in both patients with SS and SR patients in a concentration-dependent manner, but greater induction was observed for SS patients at a low concentration (10−6 M). Asthmatic serum alone showed no MKP-1expression, and there was impaired induction of MKP-1 by DEX in SR asthma patients. The expression of GLCCI1 was not induced in neutrophils with DEX or DEX/atopic asthmatic serum combination. Greater inhibition of IL-8 production was observed in neutrophils from patients with SS asthma treated with DEX/atopic asthmatic serum combination compared with SR asthma patients, though DEX alone showed the same effect on neutrophils from SS and SR asthma patients. Meanwhile, DEX dependent inhibition of constitutive neutrophil apoptosis was similar between SS asthma and SR asthma patients.

Conclusions

DEX exerted different effects on neutrophils from patients with SS asthma and SR asthma, which may contribute to glucocorticoid insensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bronchial asthma is a chronic airway inflammatory disease that affects more than 300 million people worldwide, and this number is predicted to rise to 400 million by 2020 [1, 2]. The defining features of asthma are inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, reversible airway obstruction, and airway structural remodeling [3, 4]. A large array of cytokines, chemokines, and other pro-inflammatory mediators released by both immune-inflammatory and airway structural cells contribute to the pathophysiology asthma [5–7]. Considerable evidence shows that airway inflammation is a major factor in asthma pathogenesis, and that bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma often correlates with disease severity [8].

Glucocorticoids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs used as a mainstay treatment for asthma [9]. The anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids are mediated through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which binds to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) to regulate the transcription of specific genes [10]. In most patients, asthma symptoms can be well controlled with low doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs). However, some patients require higher doses of ICSs or even oral corticosteroids to achieve optimal control, indicating that these asthma patients might be relatively resistant to the anti-inflammatory actions of corticosteroids (steroid resistant asthma). Between 10 and 25% of asthmatics are steroid resistant (SR), and do not respond to glucocorticoids (GCs) therapy [11–13]. Several studies found that steroid resistant (SR) asthmatics do not have eosinophils in their airways, but instead have neutrophils [14].

The role of neutrophils in bronchial asthma pathogenesis is controversial [15]. Previous studies demonstrated that neutrophils play a regulatory role in asthma, since they synthesize and release an array of inflammatory mediators that trigger the development of asthma [16]. Severe asthma, persistent asthmatic status, acute asthma exacerbation, and corticosteroid-resistant asthma are associated with increased numbers of neutrophils in peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum or bronchial biopsy samples from asthma patients [17, 18]. Neutrophils are generally considered to be less responsive to GCs, since events involved in neutrophil activation, including adherence, chemotaxis, degranulation, and arachidonic acid metabolite release are not effectively inhibited by glucocorticoids [19]. Many studies showed that SR asthma was associated with impaired in vitro and in vivo responsiveness of monocytes and T lymphocytes to the suppressive effects of GCs [20–22], but little is known about the responsiveness of neutrophils. In this study, we examined whether neutrophils from SS asthmatics and SR asthmatics respond differently to corticosteroids in vitro.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-eight adult asthmatic patients between the ages of 18 and 65 years were recruited from Tongji Hospital. The diagnosis of asthma was based on the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines. All subjects had a doctor’s diagnosis of symptomatic asthma and demonstrated evidence of airways hyperresponsiveness (PD20 methacholine < 2.5 mg) and/or bronchodilator responsiveness (>12% improvement in FEV1% predicted following inhalation of 200 μg salbutamol). Participants were excluded if they were current smokers or ex-smokers with a history more than 10 pack-years, had a course of oral corticosteroids, or a respiratory tract infection in the previous 4 weeks. The clinical characteristics of these participants are described in detail in Table 1. Patients’ clinical responses to corticosteroids were determined based on change in prebronchodilator FEV1 percent predicted after a one-month ICS treatment. Asthmatics were defined as SR if they had less than 15% improvement in baseline prebronchodilator FEV1. Among the 38 patients, 26 and 12 were classified as having SS and SR asthma, respectively. Blood samples were collected from all patients at their first visit of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Neutrophil isolation and cell culture

Neutrophils were separated from the heparinized peripheral blood of asthmatics using Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. Briefly, peripheral blood was mixed with hydroxyethyl starch 550 (HES-TBD 550, TBDscience, Tianjin, China) and PBS, and allowed to sediment for 30 min. The leukocyte containing supernatant was then carefully layered onto Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. After centrifugation at 800 g for 25 min, all the layers above the red cells were removed. The cells were washed after hypotonic lysis to remove erythrocytes and then resuspended at 5 × 105/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) and 10% FBS (GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) or 10% atopic asthmatic serum. This method routinely yielded a purity >98% as determined by Wright-Giemsa staining. The atopic asthmatic serum was obtained from allergic asthmatic patients with serum IgE levels >1000 IU/ml. Isolated neutrophils were treated with dexamethasone (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO USA) at a concentration of 10−6 M or 10−4 M or left unstimulated for 18 h.

Assessment of apoptosis

To detect neutrophil apoptosis, an annexinV–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) apoptosis detection kit (KGA108, KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, neutrophils were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 500 μl binding buffer containing 5 μl FITC-labeled annexin V and 5 μl propidium iodide (PI) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Apoptotic neutrophils were analyzed using a FACSCalibur with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), and were determined as the percentage of cells showing annexin V+/PI- and annexin V+/PI+ staining.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of IL-8 in cell culture supernatants were measured with a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a Human IL-8 DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a 96-well microplate was coated with capture antibody and incubated overnight at room temperature. Then, block plates by incubating with Block Buffer at room temperature for 1 h. The standards or cell supernatants were added to the plate; Detection Antibody, and streptavidin-HRP was added. After removal the unbound material by a washing procedure, substrate solution [1:1 mixture of color reagent A (H2O2) and color reagent B (tetramethylbenzidine)] was added in the dark. To stop the reaction, 2 N H2SO4 was added to each well. The optical density was determined at 450 nm and a reference wavelength of 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. Standard curve was constructed by plotting absorbance values versus the corresponding concentration of standard. Concentrations were calculated based on the standard curve. The limit of detection was 31.3 pg/mL.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from cells was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Takara, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using three-step nucleic acid precipitation with 0.2 volume of chloroform, 1 volume of isopropanol and 75% ethano. Extracted RNA was dissolved in 20 μL diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. Total RNA concentration and purity were evaluated by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo scientific Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The cDNA was prepared from 500 ng total RNA using Prime Script RT Master Mix (Takara, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the reaction mixture (10 μL) containing 2 μL 5 × Prime Script RT Master Mix was cycled at 37 °C for 15 min, 85 °C for 5 s, and 4 °C for 1 min. Real-time PCR was performed to quantify mRNA levels using an ABI Prism 7500 Real-Time System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Dalian, China). 1 μL of cDNA was used in 20-μL final PCR volume containing 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq, 0.4 μL of ROX Reference Dye II, and 0.2 μM each sense and antisense primers. The PCR parameters were 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 34 s. Results were expressed as 2–ΔΔCT, normalized to levels of β-actin in untreated cells. Gene expression was reported as the relative variation (fold change) to unstimulated cell mRNA levels. The primers used in this study were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and had the following sequences: β-actin (forward, GCAAGCAGGACTATGACGAG and reverse, CAAATAAAGCCATGCCAATC); GLCCI1 (forward, GGGAAGGAAGAAGTATCCAAGC and reverse, GCGAGTACTACTGCTCCGGTA); MKP1 (forward, GCTGTGCAGCAAACAGTCGA and reverse, CGATTAGTCCTCATAAGGTA).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SD. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by t test if the data followed a normal distribution; nonparametric tests were applied for the data that were not normally distributed. All statistical tests were two-tailed and differences were considered significant at a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Study subjects

Clinical characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. In this study patients were defined as having SR or SS asthma based on changes in lung function after 1 month of ICS treatment. Asthmatics were defined as SR if they had less than 15% improvement in baseline prebronchodilator FEV1. The patients with SS and SR asthma were similar in terms of demographics, duration of asthma, and mean FEV1 at baseline. The only clinical difference between the two patient group was changes in lung function after ICS (mean △FEV1 percent predicted); the patients with SS asthma showed significant improvement in △FEV1 (Mean ± SD) of 35.65 ± 3.70%, whereas no significant change in FEV1% predicted was noted in the patients with SR asthma with a △FEV1 (Mean ± SD) of 9.23 ± 1.15%.

In vitro markers of corticosteroid responsiveness

Neutrophils were isolated from patients’ blood at their first visit. The expression of selected gene targets was analyzed by real time PCR after treating cells with 10−6 M or 10−4 M DEX, or DEX/asthmatic serum for 18 h. MKP-1 was selected as a well-known glucocorticoid transactivation target [23]. DEX significantly induced MKP-1 expression in neutrophils from SS asthma patients in a concentration-dependent manner to produce a 6.18 ± 1.46 (P < 0.0001) and 21.38 ± 4.96-fold (P < 0.0001) at 10−6 M and at 10−4 M DEX, respectively,relative to control cells (Fig. 1a). Similarly, DEX significantly increased MKP-1 levels in neutrophils from patients with SR asthma by 3.61 ± 0.94-fold (P < 0.05) at 10−6 M and 18.88 ± 7.62-fold (P < 0.01) at 10−4 M relative to control cells (Fig. 1b). Notably, the level of MKP-1 induced by 10−6 M DEX was significantly greater in neutrophils from patients with SS asthma relative to patients with SR asthma (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). Asthmatic serum alone showed no MKP-1 expression, but when combined with DEX, asthmatic serum impaired the induction of MKP-1 by DEX in neutrophils from SR asthma patients (P < 0.05). (Fig. 1d).

MKP1 gene expression induced by dexamethasone (DEX) in asthmatic patients. Neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood of asthmatic patients and then incubated for 18 h in the absence (Con) or presence of dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M, with/without atopic asthma serum (SE). Following culture, mRNA expression of MKP1 was quantified by realtime-PCR. a and b, Neutrophils respectively from SS asthmatics (a) and SR asthmatics (b) were incubated with dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M. c, MKP-1 induction by DEX at 10−6 M was significantly greater from SS asthmatics. d, Neutrophils were isolated from asthmatic patients and incubated with DEX 10−4 M, and/or asthmatic serum (SE). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control groups

The effects of DEX on GLCCI 1 gene expression in SS and SR asthmatic patients

Glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 (GLCCI1) is expressed in both lung cells and immune cells, and its expression is significantly enhanced by the presence of glucocorticoids in asthma-like conditions [24]. Here we examined the expression of GLCCI1 mRNA in response to DEX with or without asthmatic serum in neutrophils isolated from SS and SR asthma patients. Neutrophils from participants treated with 10−6 M or 10−4 M DEX without asthmatic serum or DEX/asthmatic serum for 18 h. There was no significant change in the level of GLCCI1 in neutrophils treated with DEX from SS asthma and SR asthma patients (Fig. 2a and b). Similarly, the levels of GLCCI1 were not affected by DEX/asthmatic serum combination in SS asthma and SR asthma patients (Fig. 2c).

The effects of dexamethasone on GLCCI1 gene expression by neutrophils from asthmatic patients. Neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood of asthmatic patients and then incubated for 18 h in the absence (Con) and presence of asthmatic serum and/or dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M. Following culture, GLCCI1 mRNA expression was quantified by realtime-PCR. a and b, Neutrophils respectively from SS asthmatics (a) and SR asthmatics (b) were incubated with dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M. c, Neutrophils were isolated from asthmatic patients and incubated with DEX 10−4 M, and/or asthmatic serum (SE). * P < 0.05 compared with the control groups

DEX inhibited IL-8 production by neutrophils from SS asthmatics and SR asthmatics

The capacity of neutrophils to produce IL-8 has been documented both in vitro and in vivo and is a useful indicator of protein synthesis by activated cells [25]. We measured IL-8 production in culture to examine if DEX had different effects on activation of neutrophils isolated from SS and SR asthma patients. Neutrophils from SS asthmatics and SR asthmatics were incubated with 10−6 M or 10−4 M DEX either with or without asthmatic serum for 18 h. IL-8 levels in cell culture supernatants were then assessed by ELISA. Untreated cells produced detectable IL-8 levels, and this level increased in the presence of asthmatics serum from a basal level of 1183 ± 171.5 pg/mL to 1640 ± 156.3 pg/mL for SR asthma patients (Fig. 3). However, there was no significant change in SS asthma patients. Meanwhile, DEX significantly and dose-dependently reduced IL-8 production in neutrophils from patients with SS asthma and SR asthma. The inhibition was similar between SS asthma and SR asthma with either DEX at 10−6 M or 10−4 M (Fig. 3c). However, the asthmatics serum impaired the inhibitory activity of DEX towards neutrophils from SR asthma (Fig. 3c). Significantly greater inhibition of IL-8 production was observed with neutrophils from patients with SS asthma in the presence of DEX/asthmatic serum combination when compared with neutrophils of patients with SR asthma (P < 0 .05).

Cytokine release was inhibited by dexamethasone in patients with SS asthma and SR asthma. Neutrophils from peripheral blood of asthmatic patients(a, SS asthmatics; b, SR asthmatics) were incubated with dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M and/or asthmatic serum (SE) for 18 h. The supernatant was collected and analyzed by ELISA. Data are expressed as the means ± SD (a, b). c, Percentages of IL-8 levels for DEX or asthmatic serum compared with the amount of IL-8 produced by untreated cells (100%) are shown. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control groups

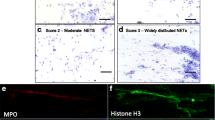

Comparison apoptosis of neutrophils from SS asthma and SR asthma patients. Neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of asthmatic patients and then incubated for 18 h in the absence (Con) or presence of asthmatic serum and/or dexamethasone (DEX) at 10−6 M or 10−4 M. Apoptosis was analyzed by measuring the binding of annexin V-FITC and PI. Data are presented in relation to the control, which was set at 100%. Data was expressed as the means ± SD. * P < 0.05 compared with the SS asthmatic control groups, # P < 0.05 compared with the SR asthmatic control groups, + P < 0.05 compared with the SS asthmatic treated with asthmatic serum groups (SE), ξ P < 0.05 compared with the SR asthmatic treated with asthmatic serum groups (SE)

DEX inhibited constitutive apoptosis of neutrophils from SS and SR asthma patients despite the presence of asthmatic serum

We next evaluated whether the effect of DEX on constitutive apoptosis of neutrophils in the presence or absence of asthmatic serum differs between SS and SR asthma patients. Constitutive apoptosis of neutrophils from SS asthma patients was inhibited by both 10−6 M and 10−4 M DEX, as was apoptosis of neutrophils from SR asthma patients (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, the addition of asthmatic serum had no effect on DEX inhibition of apoptosis of neutrophils from SS and SR asthma patients (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Here we examined the effect of DEX on neutrophils from SS asthmatics and SR asthmatics. The expression of selected markers in neutrophils that reflect the response to DEX significantly differed between SR and SS asthmatics. The ability of DEX to induce MKP-1 expression was significantly reduced in neutrophils from SR asthmatics compared to those from SS asthmatics. Additionally, the level of GLCCI1, which is significantly associated with the response of asthma patients to inhaled glucocorticoids [24], was not affected by DEX in neutrophils from asthmatics. We also assessed IL-8 production of neutrophil, an indicator of neutrophil activation [25]. The data demonstrated that more DEX was required to suppress IL-8 production by SR asthmatic neutrophils relative to SS asthmatics when asthmatic serum was added. We next demonstrated that DEX exerted a similar effect on constitutive apoptosis of neutrophils from SR and SS asthmatics. Thus, we concluded that neutrophils from SR asthma patients were less responsive to DEX, but the constitutive apoptosis was comparable to that for neutrophils from SS asthmatics.

SR asthmatics are characterized by persistent airway inflammation despite treatment with corticosteroids, and therefore these patients could be predisposed to increased airway remodeling and irreversible lung disease [11, 26, 27]. Given the increasing prevalence and severity of asthma worldwide, steroid resistance has become a challenging health problem that imposes enormous burdens on health care [28, 29]. Therefore knowledge of the mechanisms by which corticosteroids have differential effects in SS and SR asthma patients is indispensable.

MKP-1 is a phosphatase that dephosphorylates and inactivates MAPKs, including p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [23], and inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which is critical for the anti-inflammatory functions of corticosteroids [30]. Recent studies demonstrated increased activation of p38 MAPK in peripheral blood monocytes from SR asthmatics compared to those from SS asthmatics [31]. MKP-1 has also been identified by as a marker of in vitro responsiveness to corticosteroid treatment [20]. These observations prompted us to determine changes in MKP-1 expression levels in DEX-treated neutrophils isolated from asthmatic patients. DEX significantly induced MKP-1 expression in neutrophils from asthmatics, and this induction is similar to that seen for other cell types, including mast cells [32], macrophages [33], osteoblasts [34], monocytes [22] and airway smooth muscle cells (ASMC) [35]. The induction of MKP-1 expression by DEX at 10−6 M in neutrophils from SS asthma patients was higher than that for SR asthma patients. The sensitivity to glucocorticoids is correlated with MKP-1 inducibility, which provides support for the use of MKP-1 as a potential determinant of corticosteroid responsiveness. This possibility is consistent with a previous observation that of increased activation of p38 MAPK in airway macrophages isolated from severe asthmatics compared to those from non-severe asthmatics, and that the severe asthmatic group had impaired corticosteroid induction of MKP-1 [36]. Atopic asthmatic serum has been used to mimic the asthmatic milieu to sensitize airway smooth muscle cells (ASMC) [37, 38]. In this study, we used atopic asthmatic serum to passively sensitize neutrophils to simulate asthma conditions in vitro. Atopic asthmatic serum alone had no effect on MKP-1 expression by neutrophils, while neutrophil with both atopic asthmatic serum and DEX impaired DEX-induced MKP-1 expression in SR asthma patients. These data suggest that the ability of asthma milieu to reduce DEX-induced MKP-1 transcription in neutrophils from SR asthma patients may be associated with corticosteroid insensitivity.

Insensitivity to glucocorticoid is an important issue in asthma management, and may lead to poor asthma control and deterioration of airflow. Whether molecular glucocorticoid responses have a genetic component has been extensively examined [39–41]. GLCCI1 was identified as a novel pharmacogenetic determinant of the response of asthma patients to inhaled corticosteroid [24]. Indeed, Tantisira et al. reported that a functional polymorphism of GLCCI1 is associated with a substantially decreased response to inhaled glucocorticoids in patients with asthma [24]. GLCCI1 expression is rapidly induced by glucocorticoids in murine thymocytes [42]. However, here the GLCCI1 inducibility by DEX in neutrophils from asthma patients was invalid . There was no statistically significant significance in the level of GLCCI1 in SS and SR asthma neutrophils treated with DEX or asthmatic serum/DEX. This finding is consistent with previous data, wherein DEX inhibited apoptosis of neutrophils from patients with SS asthma and SR asthma to the same extent. GLCCI1 is thought to be an early marker of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis [42]. The neutrophil apoptosis suppressed by DEX may contribute to the apparent lack of GLCCI1 expression induction.

Neutrophils are generally considered to be less sensitive to GC. However, previous findings confirmed that GCs inhibit pro-inflammatory gene expression in neutrophils from different species [43–45]. IL-8 is a powerful chemoattractant and activator of neutrophils that is released by a variety of cells, including neutrophils [16], and can therefore contribute to additional recruitment and activation of neutrophils in a positive feedback manner if its expression is not tightly regulated. The gene or protein expression of IL-8 is increased in asthma patients who are insensitive to glucocorticoid treatment, as is the case for severe asthmatic patients [46, 47] and patients with neutrophilic asthma [48, 49]. We thus investigated whether differential suppression of MKP-1 expression in SS and SR asthma patients by DEX influenced IL-8 release from neutrophils. The results showed a similar inhibition of IL-8 by DEX in SS asthma and SR asthma patients, but a significantly higher inhibition was observed in neutrophils from SS than SR asthma patients treated with the DEX/asthmatic serum combination, which is consistent with the MKP-1 induction data. The insensitivity to GC of SR asthma neutrophils in the presence of a mimetic asthma milieu should also contribute to lowered responsiveness to the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release promoted by DEX.

Inducing inflammatory cell apoptosis is a key mechanism through which glucocorticoids resolve lymphocytic and eosinophilic inflammation in asthma [50]. Corticosteroids reduce the rate of neutrophil apoptosis to prolong their survival [25, 51]. In our study, DEX inhibited constitutive neutrophil apoptosis in SS asthma and SR asthma patients to the same extent. Atopic asthmatic serum slightly reduced neutrophil apoptosis in the two groups, but there was no significant difference between SS asthma and SR asthma in the presence of atopic asthmatic serum alone or in combination with DEX. Thus, the apoptosis that is inhibited by DEX is not associated with insensitivity to glucocorticoid. The increased number of neutrophils in the airways of patients with severe asthma [52], may contribute to corticosteroid resistance or refractory disease, and could be due to the lessened inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release rather than apoptosis inhibited by DEX.

Conclusions

DEX exerted different effects on neutrophils from SS asthma and SR asthma patients. No significant differences were seen in the apoptosis of neutrophils between patients with SS asthma and SR asthma, and therefore it is unlikely that glucocorticoid sensitivity is associated with the inhibition of apoptosis by glucocorticoid. DEX induced MKP-1expression and inhibited IL-8 production by neutrophils, but a reduced MKP-1 mRNA induction and IL-8 inhibition in response to DEX/asthmatic serum combination was observed in patients with SR asthma. This dysfunction may contribute to the insensitivity to glucocorticoid of these patients.

Abbreviations

- ASMC:

-

Airway smooth muscle cells

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- DEX:

-

Dexamethasone

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in one second

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GC:

-

Glucocorticoid

- GINA:

-

Global Initiative for Asthma

- GR:

-

Glucocorticoid receptor

- GRE:

-

Glucocorticoid response element

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroid

- LABA:

-

Long-acting b-agonist

- GLCCI1:

-

Glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MKP-1:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1

- PD20:

-

Dose producing a decrease of 20% from base line in FEV1

- PI:

-

Propidium iodide

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SR:

-

Steroid resistant

- SS:

-

Steroid sensitive

References

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59(5):469–78.

To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, Boulet L. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):204.

Chanez P, Humbert M. Asthma: still a promising future? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(134):405–7.

Kudo M, Ishigatsubo Y, Aoki I. Pathology of asthma. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:263.

Pawankar R, Hayashi M, Yamanishi S, Igarashi T. The paradigm of cytokine networks in allergic airway inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(1):41–8.

Barnes PJ. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3546–56.

Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Cytokines in asthma. Thorax. 1999;54(9):825–57.

Gounni AS, Wellemans V, Yang J, Bellesort F, Kassiri K, Gangloff S, Guenounou M, Halayko AJ, Hamid Q, Lamkhioued B. Human airway smooth muscle cells express the high affinity receptor for IgE (Fc epsilon RI): a critical role of Fc epsilon RI in human airway smooth muscle cell function. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2613–21.

Drazen JM, Silverman EK, Lee TH. Heterogeneity of therapeutic responses in asthma. Br Med Bull. 2000;56(4):1054–70.

Joshi T, Johnson M, Newton R, Giembycz M. An analysis of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene expression in BEAS-2B human airway epithelial cells identifies distinct, ligand-directed, transcription profiles with implications for asthma therapeutics. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(5):1360–78.

Leung DY, Bloom JW. Update on glucocorticoid action and resistance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(1):3–22. 23.

Chan MT, Leung DY, Szefler SJ, Spahn JD. Difficult-to-control asthma: clinical characteristics of steroid-insensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101(5):594–601.

Szefler SJ, Martin RJ, King TS, Boushey HA, Cherniack RM, Chinchilli VM, Craig TJ, Dolovich M, Drazen JM, Fagan JK, et al. Significant variability in response to inhaled corticosteroids for persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(3):410–8.

Nair P, Aziz-Ur-Rehman A, Radford K. Therapeutic implications of ‘neutrophilic asthma’. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21(1):33–8.

Foley SC, Hamid Q. Images in allergy and immunology: neutrophils in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(5):1282–6.

Monteseirin J. Neutrophils and asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19(5):340–54.

Macdowell AL, Peters SP. Neutrophils in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7(6):464–8.

Jatakanon A, Uasuf C, Maziak W, Lim S, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5 Pt 1):1532–9.

Schleimer RP, Freeland HS, Peters SP, Brown KE, Derse CP. An assessment of the effects of glucocorticoids on degranulation, chemotaxis, binding to vascular endothelium and formation of leukotriene B4 by purified human neutrophils. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;250(2):598–605.

Goleva E, Jackson LP, Gleason M, Leung DYM. Usefulness of PBMCs to predict clinical response to corticosteroids in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3):687–93.

Leung DY, Martin RJ, Szefler SJ, Sher ER, Ying S, Kay AB, Hamid Q. Dysregulation of interleukin 4, interleukin 5, and interferon gamma gene expression in steroid-resistant asthma. J Exp Med. 1995;181(1):33–40.

Zhang Y, Leung DYM, Goleva E. Anti-inflammatory and corticosteroid-enhancing actions of vitamin D in monocytes of patients with steroid-resistant and those with steroid-sensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1744–52.

Lasa M, Abraham SM, Boucheron C, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Dexamethasone causes sustained expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 and phosphatase-mediated inhibition of MAPK p38. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(22):7802–11.

Tantisira KG, Lasky-Su J, Harada M, Murphy A, Litonjua AA, Himes BE, Lange C, Lazarus R, Sylvia J, Klanderman B, et al. Genomewide association between GLCCI1 and response to glucocorticoid therapy in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1173–83.

Cox G. Glucocorticoid treatment inhibits apoptosis in human neutrophils. Separation of survival and activation outcomes. J Immunol. 1995;154(9):4719–25.

Goleva E, Hauk PJ, Boguniewicz J, Martin RJ, Leung DY. Airway remodeling and lack of bronchodilator response in steroid-resistant asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1065–72.

Boardman C, Chachi L, Gavrila A, Keenan CR, Perry MM, Xia YC, Meurs H, Sharma P. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid action and insensitivity in airways disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2014;29(2):129–43.

Barnes PJ, Jonsson B, Klim JB. The costs of asthma. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(4):636–42.

Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, Frazier EA, Berger M, Buist AS. Association of asthma control with health care utilization: a prospective evaluation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):195–9.

Clark AR. MAP kinase phosphatase 1: a novel mediator of biological effects of glucocorticoids? J Endocrinol. 2003;178(1):5–12.

Li LB, Leung DY, Goleva E. Activated p38 MAPK in peripheral blood monocytes of steroid resistant asthmatics. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e141909.

Kassel O, Sancono A, Kratzschmar J, Kreft B, Stassen M, Cato AC. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. EMBO J. 2001;20(24):7108–16.

Chen P, Li J, Barnes J, Kokkonen GC, Lee JC, Liu Y. Restraint of proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis by mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;169(11):6408–16.

Engelbrecht Y, de Wet H, Horsch K, Langeveldt CR, Hough FS, Hulley PA. Glucocorticoids induce rapid up-regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and dephosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and impair proliferation in human and mouse osteoblast cell lines. Endocrinology. 2003;144(2):412–22.

Issa R, Xie S, Khorasani N, Sukkar M, Adcock IM, Lee KY, Chung KF. Corticosteroid inhibition of growth-related oncogene protein-alpha via mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1 in airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):7366–75.

Bhavsar P, Hew M, Khorasani N, Torrego A, Barnes PJ, Adcock I, Chung KF. Relative corticosteroid insensitivity of alveolar macrophages in severe asthma compared with non-severe asthma. Thorax. 2008;63(9):784–90.

Hakonarson H, Carter C, Kim C, Grunstein MM. Altered expression and action of the low-affinity IgE receptor FcepsilonRII (CD23) in asthmatic airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104(3 Pt 1):575–84.

Hakonarson H, Grunstein MM. Autologously up-regulated Fc receptor expression and action in airway smooth muscle mediates its altered responsiveness in the atopic asthmatic sensitized state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(9):5257–62.

Tantisira KG, Damask A, Szefler SJ, Schuemann B, Markezich A, Su J, Klanderman B, Sylvia J, Wu R, Martinez F, et al. Genome-wide association identifies the T gene as a novel asthma pharmacogenetic locus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(12):1286–91.

Hawkins GA, Lazarus R, Smith RS, Tantisira KG, Meyers DA, Peters SP, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER. The glucocorticoid receptor heterocomplex gene STIP1 is associated with improved lung function in asthmatic subjects treated with inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1376–83.

Tantisira KG, Lake S, Silverman ES, Palmer LJ, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, Liggett SB, Gelfand EW, Rosenwasser LJ, Richter B, et al. Corticosteroid pharmacogenetics: association of sequence variants in CRHR1 with improved lung function in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(13):1353–9.

Chapman MS, Askew DJ, Kuscuoglu U, Miesfeld RL. Transcriptional control of steroid-regulated apoptosis in murine thymoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(8):967–78.

Strandberg K, Blidberg K, Sahlander K, Palmberg L, Larsson K. Effect of formoterol and budesonide on chemokine release, chemokine receptor expression and chemotaxis in human neutrophils. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23(4):316–23.

Lecoq L, Vincent P, Lavoie-Lamoureux A, Lavoie JP. Genomic and non-genomic effects of dexamethasone on equine peripheral blood neutrophils. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;128(1-3):126–31.

Al-Mokdad M, Shibata F, Takano K, Nakagawa H. Differential production of chemokines by phagocytosing rat neutrophils and macrophages. Inflammation. 1998;22(2):145–59.

Shannon J, Ernst P, Yamauchi Y, Olivenstein R, Lemiere C, Foley S, Cicora L, Ludwig M, Hamid Q, Martin JG. Differences in airway cytokine profile in severe asthma compared to moderate asthma. Chest. 2008;133(2):420–6.

Qiu Y, Zhu J, Bandi V, Guntupalli KK, Jeffery PK. Bronchial mucosal inflammation and upregulation of CXC chemoattractants and receptors in severe exacerbations of asthma. Thorax. 2007;62(6):475–82.

Simpson JL, Grissell TV, Douwes J, Scott RJ, Boyle MJ, Gibson PG. Innate immune activation in neutrophilic asthma and bronchiectasis. Thorax. 2007;62(3):211–8.

Wood LG, Baines KJ, Fu J, Scott HA, Gibson PG. The neutrophilic inflammatory phenotype is associated with systemic inflammation in asthma. Chest. 2012;142(1):86–93.

Ho CY, Wong CK, Ko FW, Chan CH, Ho AS, Hui DS, Lam CW. Apoptosis and B-cell lymphoma-2 of peripheral blood T lymphocytes and soluble fas in patients with allergic asthma. Chest. 2002;122(5):1751–8.

Liles WC, Dale DC, Klebanoff SJ. Glucocorticoids inhibit apoptosis of human neutrophils. Blood. 1995;86(8):3181–8.

Nakagome K, Matsushita S, Nagata M. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158 Suppl 1:96–102.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who volunteered for the study; Wang Ni, Shixin Chen and Kun Zhang for spirometry measurement.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81570033, 81570047, 81470227, 81370145, 81370156), National key basic research and development program (973 Program, No. 20l5CB553403), Chinese medical association research project (No. 2013BAI09B00) and Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (No. IRT_14R20).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

WM recruited patients, collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and wrote the draft. GP, WX, CY, FY, YQ recruited patients, collected data. XY analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript. ZJ and XJ conceived and designed the study, recruited patients, and drafted the manuscript for important intellectual content. XJ provided overall supervision and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved this study (IRB ID: 20120410). All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Gao, P., Wu, X. et al. Impaired anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoid in neutrophil from patients with steroid-resistant asthma. Respir Res 17, 153 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0462-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0462-0