Abstract

Background

Inhaled long-acting beta2agonists used alone and in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid reduce the risk of exacerbations in patients with stable COPD. However, the relative efficacy of these agents in preventing recurrent exacerbations in those recovering from an initial episode is not known. This study compared the rate of COPD exacerbations over the 26 weeks after an initial exacerbation in patients receiving the combination of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol (FP/SAL) or SAL alone.

Methods

Patients (n = 639) aged ≥40 years were randomized to either twice-daily inhaled FP/SAL 250/50 μg or SAL 50 μg. Primary, and secondary, endpoints were rates of recurrent severe, and moderate/severe, exacerbations of COPD. Lung function, health outcomes and levels of biomarkers of systemic inflammation were also assessed.

Results

There was no statistically significant treatment difference in rates of recurrent severe exacerbations (treatment ratio 0.92 [95% CI: 0.58, 1.45]) and moderate/severe exacerbations (0.82 [0.64, 1.06]) between FP/SAL and SAL in the intent-to-treat population. Pre-dose morning FEV1change from baseline was greater (0.10 L [0.04, 0.16]) with FP/SAL than SAL. No treatment difference was seen for other endpoints including patient-reported health outcomes and biomarker levels for the full cohort.

Conclusions

No significant treatment difference between FP/SAL and SAL was seen in COPD exacerbation recurrence for the complete cohort. Treatment benefit with FP/SAL over SAL (treatment ratio 0.68 [0.47, 0.97]) was seen in patients having FEV1≥ 30% and prior exposure to ICS. No unexpected safety issues were identified with either treatment. Patients with the most severe COPD may be more refractory to treatment.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01110200). This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (study number ADC113874).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exacerbations are clinically important events in COPD [1], becoming more frequent and more severe as airflow limitation worsens [2]. A frequent exacerbator phenotype independent of baseline FEV1has also been identified [3]. Increased frequency of exacerbations has also been associated with an accelerated decline in lung function [4],[5], worse health status [6],[7], increased mortality and morbidity, and high healthcare costs [8]. Furthermore, exacerbations have been shown to exhibit temporal clustering and patients are more likely to suffer an exacerbation in the period immediately following an index exacerbation [9]. There is also an increased risk of co-morbid events associated with systemic inflammation in the aftermath of an exacerbation [10]-[12]. Reducing the frequency and recurrence of exacerbations is therefore a therapeutic priority in COPD [13].

Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and long-acting beta2agonists (LABA) combination therapy has been found to reduce recurrence of COPD exacerbations and subsequent rehospitalization and mortality [14], and to significantly reduce rates of moderate or severe exacerbations, relative to treatment with LABA alone [15]. However, in previous large-scale studies of ICS/LABA therapy, randomization took place up to 1 year after the index exacerbation event [16],[17].

In this study, patients with COPD received double-blind treatment, commencing within 14 days following an initial exacerbation, with either an ICS/LABA combination of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL) in a single inhaler, or a LABA alone, SAL monotherapy. The aim of the study was to compare treatment effects on the rate of COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization, and requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids (OCS) or OCS and antibiotics. Additional endpoints included measures of lung function and health status, incorporating EXACT-PRO (EXAcerbations of Chronic Pulmonary disease Tool – Patient Reported Outcome), a new measure of exacerbation frequency, severity and duration [18]. Levels of three inflammatory biomarkers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Clara Cell secretory protein 16 (CC-16), and surfactant protein D (SP-D), were measured to investigate a possible association between systemic inflammation, exacerbation frequency [19] and severity of disease [20].

Methods

Study population

Male and female patients with COPD [21] aged ≥40 years were eligible for enrollment if they had recent (≤14 days) history of exacerbation requiring: a)hospitalization for ≤10 days; b)emergency room observation of duration ≥24 hours during which OCS/OCS + antibiotics treatment was administered; or c)physician’s office or emergency room visit of <24 hours duration with OCS/OCS + antibiotics treatment plus 6-month history of exacerbation-related hospitalization. Full details of inclusion and exclusion criteria, permitted and prohibited medications are provided in Additional file 1. Each participating patient provided written informed consent prior to study entry. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and approved by the applicable ethics committee or institutional review board at each site (Additional file 2).

Study design

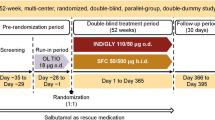

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, active-comparator study (GSK study ADC113874; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01110200) conducted in 81 centers in the United States, Argentina and Norway, from April 2010 to May 2012. Patients received FP/SAL 250/50 μg or SAL 50 μg for self-administration twice daily via DISKUS™ inhaler during a 21-day ‘stabilization period’ beginning within 14 days post-discharge and for a subsequent 26-week treatment period. Clinic visits were scheduled post-discharge: within 14 days; at 21 days; at 3 months; and at 6 months. Patients were randomized to study treatment within 14 days of discharge from hospital or emergency room, or of the physician’s office visit for the index exacerbation. A chronological diagram of the experimental design is presented in Figure 1. Patients requiring prolonged (protocol-defined as a period of up to 28 days) treatment with OCS and/or antibiotics during the stabilization period were to be withdrawn from the study.

Chronological schematic of experimental design.Note: 1. Duration of index hospitalization is ≤10 days. Time from hospital discharge, ER, or physician’s office visit (due to the recent exacerbation) to Randomization (Visit 2) is ≤14 days. Visit 1 (Screening) and Visit 2 can occur during the hospitalization, ER visit, physician’s office visit, and up to 14 days afterward. 2. Duration of subjects’ participation in study is 29 weeks (completing subjects), approximately (unless subject is prematurely withdrawn from the study). ER: Emergency Room; F/U: Follow-up; TC: Telephone call; V: Visit; Wks: Weeks.

Randomization (1:1) was according to a schedule, stratified by background tiotropium use and prior ICS use, generated by the sponsor using internally validated software (RandAll, GlaxoSmithKline, UK). Allocation of double-blinded study treatments was conducted using RAMOS (GlaxoSmithKline, UK), an interactive voice-response system.

Efficacy analyses

The primary endpoint was the estimated annualized rate of exacerbations requiring hospitalization (severe exacerbations). The secondary endpoint was rate of exacerbations requiring treatment with OCS, antibiotics and/or hospitalization, alone and in combination (moderate or severe exacerbations). Exacerbations were identified by the worsening for at least two documented consecutive days of at least two of: dyspnea, sputum volume, sputum purulence, or at least one of these combined with sore throat, cold symptoms, fever, or increased cough or wheeze.

Other efficacy endpoints included time to first moderate or severe exacerbation; probability of all-cause premature withdrawal from the study; pre-dose morning FEV1; supplemental use of albuterol; changes in biomarker levels; and patient-reported health outcomes (CRQ-SAS; EXACT-PRO, Additional file 3).

Post-Hoc subgroup analyses

Post-hocanalyses of exacerbation rate and spirometry data were performed for patient subgroups defined by baseline post-bronchodilator % predicted FEV1(<30%/≥30%) and prior ICS use or concurrent tiotropium use. An additional subgroup analysis compared pre-dose FEV1and questionnaire scores for patients experiencing ≥1 or 0 on-treatment exacerbations.

Safety analyses

Adverse events (AEs) were documented by the study investigators at each on-treatment visit and on a follow-up call 2 weeks following completion of the study or discontinuation of study medication, and coded using MedDRA. Blood pressure and heart rate measurements were collected at each visit.

Statistical analysis

All efficacy and safety analyses were performed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, consisting of all eligible patients randomized to study treatment. The study aimed to recruit an ITT population of 720 patients, which would provide 90% power to detect a treatment effect on the primary efficacy endpoint of 44% at the 0.05 significance level; this estimate was based on previously observed severe exacerbation rates (0.28–0.50) in patients with 1-year history of COPD-related hospitalization [16],[17].

The primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using a negative binomial regression model with terms for treatment group, pooled investigator, randomization stratum, and baseline % predicted FEV1. Log (time of treatment) was an offset variable. To account for multiple comparisons for several efficacy endpoints, a step-down statistical hierarchy was implemented. Statistical methods used to analyze other efficacy endpoints are detailed in Additional file 3.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Of 734 patients screened, 639 formed the ITT population (Figure 2). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 1).

Exacerbation results

No statistically significant treatment differences between FP/SAL and SAL in rates of recurrent severe or moderate/severe exacerbations were observed in the ITT population (severe exacerbations: FP/SAL 0.44, SAL 0.48, P =.710; moderate/severe exacerbations: FP/SAL 1.49, SAL 1.81, P =.136) (Table 2). Because of the step-down statistical hierarchy, all other analyses were interpreted descriptively.

A post-hocanalysis of annualized exacerbation rates indicated that patients in a subgroup (n = 373) with baseline post-bronchodilator % predicted FEV1≥ 30% and history of prior ICS experienced fewer exacerbations with FP/SAL (mean annualized exacerbation rate: 1.54) than SAL (2.28) (treatment ratio 0.68 [0.47, 0.97]) (Table 2). A greater proportion of patients in subgroups having % predicted FEV1< 30% relative to ≥30% used tiotropium during the study (46% vs. 37%).

There was no overall indication of treatment differentiation for either time to first moderate/severe exacerbation, or withdrawal from the study during the treatment period (Table 3; Figure 3). Exacerbation frequency decreased as the treatment period progressed (Figure 4). In the first 4 weeks following the 3-week stabilization period, slightly more moderate/severe exacerbations occurred in the SAL arm than FP/SAL (49 vs. 39 exacerbations).

Kaplan-Meier estimates for A) time to first COPD exacerbation requiring oral corticosteroids, antibiotics and/or hospitalization, and B) time to withdrawal from study, over 26 weeks of treatment following the 3-week stabilization period, ITT population.COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FP = fluticasone propionate; ITT = intent-to-treat; SAL = salmeterol.

A post-hoc analysis of patient withdrawal during the 3-week stabilization period found that 65 (10%) patients withdrew from the study for any reason (FP/SAL 26 [8%], SAL 39 [12%]) (Table 4). Of these, 39 (6%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy or AE (FP/SAL 15 [5%], SAL 24 [7%]).

Other efficacy outcomes

Pre-dose morning FEV1findings suggested a treatment difference in favor of FP/SAL, overall (Figure 5) and across patient subgroups (Table 5). A greater treatment effect of adding FP to SAL on FEV1was seen in patients with post-bronchodilator % predicted FEV1≥ 30% not receiving concurrent tiotropium. There was no notable treatment difference in patients receiving concurrent tiotropium.

There was no treatment difference in rescue medication use (data not shown) or for any health outcome comparisons (Additional file 4: Table S1) at study endpoint. In a secondary analysis, patients who did not experience on-treatment exacerbations showed significantly more improvement in the dyspnea domain of CRQ-SAS [22] and in EXACT-PRO total score at study endpoint than those who did. There were also some indications of greater improvement in other CRQ-SAS domains (Additional file 5: Table S2). However, no difference in change from baseline pre-dose FEV1was observed between patients who did not experience on-treatment exacerbations and those who did (data not shown).

Levels of all three inflammatory biomarkers were elevated at baseline and remained elevated throughout the 26-week assessment period; no treatment effect on biomarker levels was observed (Additional file 6: Table S3). No meaningful associations between biomarker levels and occurrence of on-treatment exacerbation were observed. Treatment of the index events may have altered the initial level of the biomarker assay.

Safety outcomes

AE and serious AE frequencies were comparable between the treatment groups (Table 6). The incidence of pneumonia (FP/SAL: 4%, SAL: 3%) was consistent with previous observations from FP/SAL exacerbation studies [23]. Seven fatal AEs occurred during the treatment period (FP/SAL: 4; SAL: 3) (Additional file 7).

Discussion

No statistically significant treatment difference in the primary endpoint of this study, the rate of COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization, assessed over six months, was achieved. The lack of exacerbation reduction was noted despite the positive spirometric data supporting the clinical benefit of the FP/SAL compared with SAL. FP/SAL has previously been shown to reduce the frequency of moderate/severe exacerbations compared with SAL in patients with a prior history of exacerbations in parallel 52-week studies [16],[17].

The objective of the study was to evaluate the treatment effects of FSC 250/50 mcg BID in comparison to salmeterol 50 mcg BID, both via DISKUS, on exacerbations of COPD requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids, antibiotics, and/or hospitalization (alone and in combination), over a 29-week treatment period. The primary efficacy measure was the rate of exacerbation requiring hospitalization. Although treatment intervention with ICS/LABA combination therapy was known to reduce the rate of exacerbations more effectively that LABA alone therapy in clinically stable patients with a history of exacerbation, we aimed to investigate the potential benefit of an early treatment intervention immediately following a moderate to severe exacerbation of COPD. The potential benefits of this treatment paradigm had not been studied previously, is not widely accepted but has major clinical relevance given the increasing focus on hospital readmission, particular in the United States. While many patients who experience an acute exacerbation of COPD recover quickly, mortality exceeds 10% during hospitalization, increases to 25-40% during the year after hospital discharge [24] and 63% of discharged patients experience subsequent exacerbations and readmissions [25]. Other data show that although 75% of those patients who survive regain their basal pulmonary function within five weeks post-hospitalization, 7% of patients do not recover even after five months following the acute episode [20],[26]. Hence, the study was initiated in an attempt to address these clinical outcomes.

In the 3-year TORCH study, in which 57% of subjects had an exacerbation within the preceding year, adding FP to SAL resulted in a significant reduction in moderate/severe exacerbations and in exacerbations requiring OCS, but not in severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization. Concurrent long-acting bronchodilators (including tiotropium) were not permitted in these earlier studies, but were allowed in the present trial and may have impacted the results discussed below. The findings of a meta-analysis of 18 randomized trials of ICS/LABA combination therapy [27] concurred with those of TORCH, identifying a significant benefit of the combination on moderate, but not severe, exacerbations.

Unlike the studies described above, our study was designed to investigate the effect on severe exacerbation rates of ICS intervention in the period shortly after an acute COPD exacerbation. This endpoint is of particular interest to United States clinicians, as 30-day re-admission following exacerbation will be subject to financial penalties imposed by the Centre for Medicare and Medicaid Services under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program [28]. All patients in this study had exacerbation requiring hospitalization and/or treatment with OCS within the month prior to randomization.

Our findings are consistent with previous observations of a high-risk period for recurrence within 8 weeks of index exacerbation [9]. To allow sufficient time for patients to recover from the index exacerbation before the start of outcome measure assessment, patients experiencing an exacerbation during the 21-day stabilization period were to be withdrawn and those exacerbations were not included in the efficacy analyses. A potential confounding factor was that more patients receiving SAL than FP/SAL withdrew from the study during the 21-day stabilization period for any reason including lack of efficacy and/or AE. More patients receiving SAL, compared with FP/SAL, experienced a moderate/severe exacerbation in the first month of treatment. These observations may indicate a potential benefit of immediate post-event treatment with ICS/LABA maintenance therapy in reducing the likelihood of hospital readmission in the 30 days post-event. However, the study was not designed to test this hypothesis; furthermore, a substantial proportion (>60%) of readmissions of patients initially hospitalized for COPD are due to factors other than COPD recurrence [29] and hence may not be influenced by choice of COPD maintenance therapy. The safety profiles of the two treatments are consistent with previous findings [30].

A post-hocanalysis of moderate/severe exacerbation rates identified that patients with greater lung function (% predicted FEV1≥ 30%) and prior use of ICS receiving FP/SAL versus SAL had 32.3% lower annualized exacerbation rate. This effect size is similar to that observed previously in 52-week studies of FP/SAL and SAL in which concurrent tiotropium was not permitted [16],[17]. These findings suggest a possibility of achieving a significant reduction in recurrence by targeting post-exacerbation treatment at subgroups of patients who display defined characteristics associated with recurrence or ICS responsiveness [31],[32]. They also suggest a greater potential effect on risk of recurrence of exacerbations following withdrawal of ICS therapy, an observation consistent with previously reported findings [33],[34].

Clinically meaningful improvement from baseline in pre-dose FEV1was seen with FP/SAL (+140 mL) but not SAL (+40 mL). No treatment difference was observed in the third of patients using concurrent tiotropium. The inclusion of patients using concurrent tiotropium in the cohort may have confounded the treatment effect. A one-year study of patients with a history of prior exacerbation within the preceding year found that adding SAL to tiotropium, with and without FP, did not significantly reduce exacerbation rate overall, although a significant reduction in severe exacerbation rate was observed with SAL + FP + tiotropium triple therapy compared to treatment with tiotropium alone [35]; however, this study was under powered to demonstrate an effect on this variable; whereas adding tiotropium to ICS/LABA combination therapy conferred significant benefits in mortality, hospitalizations, and OCS use in a retrospective cohort analysis [36]. Furthermore, a two-year study comparing FP/SAL with tiotropium on exacerbation rate did not find a significant treatment difference [37].

No treatment difference in health outcomes (CRQ-SAS or EXACT-PRO) was seen. Levels of inflammatory biomarkers, heightened across the cohort as anticipated due to the index exacerbation event [38], did not decrease substantially over the treatment period, and no treatment difference was observed. Both systemic inflammation and airway inflammation are associated with COPD exacerbations [39]. Although the persistence of inflammatory biomarkers subsequent to exacerbation has been reported [40], no clear relationship between biomarker levels and on-treatment exacerbation was found. The persistence of high biomarker levels across the study cohort over the 6-month study was an unexpected finding requiring further investigation, but may be reflective of disease severity and systemic inflammation.

Cross-cohort variables and challenges in the recruitment of patients shortly after an exacerbation were evident in this study. Recruitment was complicated by significant co-morbidities found in the target cohort, which frequently were cause for exclusion, by the difficulty of coordinating patient hospitalization, discharge and consent for study participation, and by the limited availability of investigators with both outpatient and inpatient practices qualifying them to participate in the study. The identification of such recruitment issues emphasizes the need for careful cohort definition in future studies of the timely treatment of COPD exacerbation risk. Defining eligibility criteria on the basis of prior treatment with ICS may help to identify a steroid-responsive cohort. The observation of baseline FEV1below a defined threshold may help identify patients who are less likely to respond to treatment. Another factor that may have affected responsiveness to treatment was the unexpectedly low exacerbation rate seen in both study arms, possible explanations for which include the use of concurrent tiotropium by patients and temporal improvements in patient care. While the results of this study were negative, the implementation of lessons herein learned may result in future studies being appropriately powered to detect a statistically significant treatment effect on rehospitalization rate, to assist clinicians to identify COPD phenotypes, including the presence or absence of common COPD co-morbidities, most likely to benefit from ICS/LABA intervention immediately following an exacerbation [41].

Although the primary and other pre-specified outcomes of this study did not show statistical significance, the data support previous findings of significant beneficial effect of combination therapy on lung function [15]. Data on withdrawals during the 21-day stabilization period and exacerbations during the first month of the 26-week treatment period suggest a potential benefit of ICS/LABA in the period immediately following an exacerbation, and may warrant further clinical investigation. It is worth noting the findings of a post-hoc analysis, which showed that the rate of on-treatment study withdrawal due to lack of efficacy in the SAL arm (4%; n = 13) was approximately double that observed in the FP/SAL arm (2%; n = 5); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.062). The outcome of post-hocsubgroup analysis, which identified a greater effect of ICS/LABA on exacerbation rates in patients with predicted FEV1≥ 30% and prior use of ICS, underscored the potential importance of considering patient-specific factors in post-exacerbation treatment decisions, and suggested an ICS withdrawal effect [33].

The findings of this study highlight the complexity of studying interventions in the post-exacerbation period and emphasize the impact that patient-specific clinical factors and concomitant medication use may have on outcomes. In addition, future studies should be designed to capture recurrent or continued exacerbations in the immediate recovery period.

Authors’ contributions

JAO, GDC, ANM and IR: contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and to the critical review of the manuscript, including review and approval of the final version to be published. AE contributed to the conception and design of the study, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the critical review of the manuscript, including review and approval of the final version to be published. TJF contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition of the data, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and to the critical review of the manuscript, including review and approval of the final version to be published. PSS contributed to the acquisition of the data and to the critical review of the manuscript, including review and approval of the final version to be published. MTD contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of the data, and to the critical review of the manuscript, including review and approval of the final version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- AECOPD:

-

Acute exacerbation of COPD

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- ATS:

-

American thoracic society

- CC-16:

-

Clara cell secretory protein 16

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRQ-SAS:

-

Chronic respiratory disease questionnaire - self-administered standardized format

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- EXACT-PRO:

-

Exacerbations of chronic pulmonary disease tool - patient reported outcome

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FP:

-

Fluticasone propionate

- FP/SAL:

-

Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- hs-CRP:

-

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ITT:

-

Intent-to-treat

- LABA:

-

Long-acting beta2agonist

- LS:

-

Least squares

- MedDRA:

-

Medical dictionary for regulatory activities

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- OCS:

-

Oral corticosteroids

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse event

- SAL:

-

Salmeterol

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SP-D:

-

Surfactant protein D

References

Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA: COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet. 2007, 370: 786-796. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61382-8.

Jenkins CR, Celli B, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, Jones PW, Vestbo J, Yates JC, Calverley PM: Seasonality and determinants of moderate and severe COPD exacerbations in the TORCH study. Eur Respir J. 2012, 39: 38-45. 10.1183/09031936.00194610.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, M Llerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, Calverley P, Rennard S, Wouters EF, Wedzicha JA: Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 1128-1138. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883.

Vestbo J, Edwards LD, Scanlon PD, Yates JC, Agusti A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, Lomas DA, MacNee W, Miller BE, Silverman EK, Tal-Singer R, Wouters E, Rennard SI: Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. New Engl J Med. 2011, 365: 1184-1192. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105482.

Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA: Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002, 57: 847-852. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847.

Nishimura K, Sato S, Tsukino M, Hajiro T, Ikeda A, Koyama H, Oga T: Effect of exacerbations on health status in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009, 7: 69-10.1186/1477-7525-7-69.

Spencer S, Calverley PMA, Burge PS, Jones PW: Impact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004, 23: 698-702. 10.1183/09031936.04.00121404.

Anzueto A: Impact of exacerbations on COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2010, 19: 113-118. 10.1183/09059180.00002610.

Hurst JR, Donaldson GC, Quint JK, Goldring JJP, Baghai-Ravary R, Wedzicha JA: Temporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 179: 368-374. 10.1164/rccm.200807-1067OC.

Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P: Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012, 67: 957-963. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518.

Halpin DMG, Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Leimer I, Tashkin DP: Risk of nonlower respiratory serious adverse events following COPD exacerbations in the 4-year UPLIFT® trial. Lung. 2011, 189: 261-268. 10.1007/s00408-011-9301-8.

Seemungal T, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, Moric I, Sanderson G, Message S, Maccallum P, Meade TW, Jeffries DJ, Johnston SL, Wedzicha JA: Respiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 164: 1618-1623. 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2105011.

Executive Summary: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2013

Soriano JB, Kiri VA, Pride NB, Vestbo J: Inhaled corticosteroids with/without long-acting beta2agonists reduce the risk of rehospitalization and death in COPD patients. Am J Respir Med. 2003, 2: 67-74. 10.1007/BF03256640.

Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, Yates JC, Vestbo J: Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 775-789. 10.1056/NEJMoa063070.

Ferguson GT, Anzueto A, Fei R, Emmett A, Knobil K, Kalberg C: Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 microg) on COPD exacerbations. Respir Med. 2008, 102: 1099-1108. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.04.019.

Anzueto A, Ferguson GT, Feldman G, Chinsky K, Seibert A, Emmett A, Knobil K, O'Dell D, Kalberg C, Crater G: Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50) on COPD exacerbations and impact on patient outcomes. COPD. 2009, 6 (5): 320-329. 10.1080/15412550903140881.

Leidy NK, Wilcox TK, Jones PW, Roberts L, Powers JH, Sethi S: Standardizing measurement of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: reliability and validity of a patient-reported diary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011, 183: 323-329. 10.1164/rccm.201005-0762OC.

Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Edwards LD, Locantore NW, Miller BE, Horstman DH, Tal-Singer R: Serum surfactant protein D is steroid sensitive and associated with exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009, 34: 95-102. 10.1183/09031936.00156508.

Dickens JA, Miller BE, Edwards LD, Silverman EK, Lomas DA, Tal-Singer R: COPD association and repeatability of blood biomarkers in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res. 2011, 12: 146-10.1186/1465-9921-12-146.

Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995, 152: S78-S121. 10.1164/ajrccm/152.5_Pt_2.S78.

Schünemann JH, Puhan M, Goldstein R, Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH: Measurement properties and interpretability of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). COPD. 2005, 2: 81-89. 10.1081/COPD-200050651.

ADVAIR DISKUS™: Full Prescribing Information. 2008

Escarrabill J: Discharge planning and home care for end-stage COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2009, 34: 507-512. 10.1183/09031936.00146308.

Hernandez C, Jansa M, Vidal M, Nuñez M, Bertran MJ, Garcia-Aymerich J, Roca J: The burden of chronic disorders on hospital admissions prompts the need for new modalities of care: a cross-sectional analysis in a tertiary hospital. QJM. 2009, 102: 193-202. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn172.

Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA: Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000, 161: 1608-1613. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022.

Rodrigo GJ, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Plaza V: Safety and efficacy of combined long-acting β-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids vs long-acting β-agonists monotherapy for stable COPD. Chest. 2009, 136: 1029-1038. 10.1378/chest.09-0821.

Readmissions Reduction Program. 2013

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA: Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. New Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 1418-1428. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563.

Hanania NA1, Darken P, Horstman D, Reisner C, Lee B, Davis S, Shah T: The efficacy and safety of fluticasone propionate (250 μg)/salmeterol (50 μg) combined in the Diskus inhaler for the treatment of COPD. Chest. 2003, 124: 834-843. 10.1378/chest.124.3.834.

Sethi S: Personalised medicine in exacerbations of COPD: the beginnings. Eur Respir J. 2012, 40: 1318-1319. 10.1183/09031936.00136412.

Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, Mistry V, Pancholi M, Venge P, Lomas DA, Barer MR, Johnston SL, Pavord ID, Brightling CE: Blood eosinophils to direct corticosteroid treatment of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012, 186: 48-55. 10.1164/rccm.201108-1553OC.

Wouters EF, Postma DS, Fokkens B, Hop WC, Prins J, Kuipers AF, Pasma HR, Hensing CA, Creutzberg EC: Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2005, 60: 480-487. 10.1136/thx.2004.034280.

van der Valk P, Monninkhof E, van der Palen J, Zielhuis G, Van Herwaarden C: Effect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: the COPE study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166: 1858-1868. 10.1164/rccm.200206-512OC.

Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Goldstein R, Balter M, O'Donnell D, McIvor A, Sharma S, Bishop G, Anthony J, Cowie R, Field S, Hirsch A, Hernandez P, Rivington R, Road J, Hoffstein V, Hodder R, Marciniuk D, McCormack D, Fox G, Cox G, Prins HB, Ford G, Bleskie D, Doucette S, Mayers I, Chapman K, et al: Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 146: 545-555. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00152.

Short PM, Williamson PA, Elder DHJ, Lipworth SIW, Schembri S, Lipworth BJ: The impact of tiotropium on mortality and exacerbations when added to inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonist therapy in COPD. Chest. 2012, 141: 81-86. 10.1378/chest.11-0038.

Wedzicha JA1, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA: The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 177: 19-26. 10.1164/rccm.200707-973OC.

Koutsokera A, Stolz D, Loukides S, Kostikas K: Systemic biomarkers in exacerbations of COPD: the evolving clinical challenge. Chest. 2012, 141: 396-405. 10.1378/chest.11-0495.

Groenewegen KH, Postma DS, Hop WCJ, Wielders PLML, Schlösser NJJ, Wouters EFM: Increased systemic inflammation is a risk factor for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2008, 133: 350-357. 10.1378/chest.07-1342.

Perera WR, Hurst JR, Wilkinson TM, Sapsford RJ, M Llerova H, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA: Inflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2007, 29: 527-534. 10.1183/09031936.00092506.

Fingleton J, Weatherall M, Beasley R: Towards individualised treatment in COPD. Thorax. 2011, 66: 363-364. 10.1136/thx.2010.155564.

Acknowledgements

We thank all investigators and patients who participated in this study. This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. All authors had full access to the data and were responsible for the decision to publish the paper. Editorial support (in the form of development of a draft outline in consultation with the authors, development of a manuscript first draft in consultation with the authors, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this paper, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, referencing and graphic services) was provided by Ian Grieve, PhD at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

JAO has served on advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim; PSS has received research support from the NIH, GlaxoSmithKline, Forest and Allegro Diagnostics; MTD has served as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline and Ikaria, and his institution has received research support from the NIH, Aeris, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Centocor, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Otsuka, Pearl, Pulmonx and Pfizer. GDC, AE, TJF, ANM and IR are employees of and hold stock in GlaxoSmithKline.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 3: Statistical methods used in the analysis of other efficacy endpoints.(DOCX 25 KB)

12931_2014_105_MOESM4_ESM.docx

Additional file 4: Table S1.: CRQ-SAS Change from Baseline at 3 + 26-Week Study Endpoint and EXACT-PRO Total Score and Components at Study Endpoint, ITT Population. (DOCX 24 KB)

12931_2014_105_MOESM5_ESM.docx

Additional file 5: Table S2.: Change from Baseline CRQ-SAS Domain Scores and EXACT-PRO Total Scores at Treatment Period Weeks 13 and 26 and at 26-Week Endpoint for Patients Having 0 or ≥1 On-Treatment Exacerbations, ITT Population. (DOCX 26 KB)

12931_2014_105_MOESM6_ESM.docx

Additional file 6: Table S3.: Change from Baseline at 3 + 26-Week Study Endpoint for Biomarkers of Systemic Inflammation, ITT Population. (DOCX 25 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohar, J.A., Crater, G.D., Emmett, A. et al. Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol 250/50 μg versus salmeterol 50 μg after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Respir Res 15, 105 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0105-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0105-2