Abstract

Background

There have been some studies of common primary care diseases in Japan, but no reports on which diseases it is difficult for general physicians to diagnose in daily practice. In this study, we identified diseases that provided a diagnostic challenge for Japanese general physicians in daily practice.

Methods

The subjects were new undiagnosed patients referred to the General Outpatient Department of Chiba University Hospital during the one-year period from January 2008. We performed a retrospective chart review to identify the referring doctor, patient demographics, the duration of symptoms, the final diagnosis, and the outcome. Final diagnoses were classified according to the International Classification of Primary Care Second Edition (ICPC-2). In addition, the differences between referrals from general physicians and those from other physicians were assessed. Fisher’s exact test and the Bonferroni-Holm correction were used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 169 patients were referred by general physicians and 239 patients were referred by other physicians. The most common ICPC-2 diagnosis was “General & Unspecified” conditions (35 patients, 20.7%), followed by “Psychological” conditions (31 patients, 18.3%) and “Musculoskeletal” conditions (21 patients, 12.4%). No significant differences of the ICPC-2 category for the final diagnosis and each diagnosis were found between patients referred by general physicians and those referred by other physicians. The hospitalization rate was lower for patients referred by general physicians than for patients referred by other physicians (4 patients, 2.4% vs. 24 patients, 10.0%) (P = 0.002).

Conclusions

Japanese general physicians found difficulty in diagnosing “Psychological” conditions, “Musculoskeletal” conditions, variations within the normal range, and viral infections that required diagnosis by exclusion. Because most of the patients referred by general physicians had mild conditions, further education at outpatient departments and clinics is required to improve diagnostic performance. Additionally, it is important to increase the gatekeeper role of general physicians and further development of the medical system by the government to distinguish the functions of clinics and hospitals is expected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

All citizens in Japan are covered by a national health insurance system in which there are no official “gatekeepers”. Patients can freely choose between attending a local physician’s office (clinic) or a hospital and Japanese physicians can freely practice internal medicine [1]. But recently, Japan has faced the problems of a rapidly aging population, financial constraints, and both a shortage and unbalanced distribution of doctors, with the need to improve the primary care system and delivery of general medicine being pointed out [2]. Primary care physicians are expected to perform a wide range of roles, such as management and prevention of common diseases, and one of their vital tasks is to detect patients with serious diseases among the many patients they encounter in daily practice [3],[4]. Patients who present to general practitioners are often at an early stage in the natural history of their disease and have vague, atypical or confusing symptoms, resulting in a wide range of diagnostic possibilities [5]. In Japan, general physicians can refer their patients to specialists at any medical institutions for diagnosis or treatment with a referral letter. When patients visit an advanced treatment hospital without referral from a primary care physician, they have had to pay an additional charge since 1996 [6],[7].

There have been some studies of common primary care diseases in Japan, but no investigations into which diseases present diagnostic difficulty for general physicians working in community based primary care [8],[9]. Chiba University Hospital is located in the western part of Chiba Prefecture near Tokyo, and is a tertiary medical institution with 36 specialist departments that is designated as an advanced treatment hospital. In the present study, we investigated the final diagnoses of patients referred to the General Medicine Department to determine the diseases that are difficult for Japanese general physicians to diagnose in daily practice. We also assessed the differences between referrals from general physicians and those from other physicians.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects were new patients who were referred to the General Medicine Department of Chiba University Hospital for diagnosis during the one-year period from January 2008. Their medical records were retrospectively reviewed and information was stored in a database. The following data were collected: the referring doctor, patient demographics (age and sex), the duration of symptoms, the final diagnosis, the final diagnostic category according to the International Classification of Primary Care Second Edition (“ICPC-2”), and the presence/absence of specialist treatment and hospitalization after diagnosis. The General Medicine Department is part of the Internal Medicine Department, and staff physicians provide initial treatment for patients who present during office hours after referral from other departments of the hospital or from other medical centers, including those of general physicians. In Japan there is no official recognition of “family physicians” or “general practitioners” by the government. Accordingly, we categorized physicians working at general internal medicine clinics as “general physicians” and physicians working at specialist clinics or hospital physicians as “other physicians”.

Diagnosis

At our department, the diagnosis was made by a team of 3 staff physicians who assessed each new patient. If it was difficult to make a diagnosis, a medical board was held at the department and we referred the patient to an appropriate specialist, if necessary. Diagnoses that were assigned to categories without specific findings, such as unspecified viral infections and adverse reactions to medications, were only made after taking a detailed history and performing physical examination, blood tests, and imaging as required. For psychiatric diseases, the diagnosis was made by consensus of two physicians from the General Medicine Department after careful investigation to detect any physical disease. If making a diagnosis was difficult, we referred the patient to a psychiatrist. After checking the initial diagnosis and medical records over a 1-year follow-up period, the latest diagnosis was selected as the final one. If there was more than one diagnosis, the principal diagnosis was defined as the final diagnosis.

Ethics

Patient numbers were coded for information processing and were destroyed upon completion of the investigation. Since the names were not attached to the information, individual patients could not be identified. This study received approval from the Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine Ethics Board (number 1057).

Statistical analysis

Differences of the ICPC-2 diagnostic classifications, the final diagnosis, and the presence/absence of specialist treatment and hospitalization between patients referred by general physicians and by other physicians were assessed for statistical significance using Fisher’s exact test, and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for each analysis. Because analysis of the ICPC-2 category (18 categories) and the final diagnosis (38 diseases) involved multiple comparisons, correction was done by a post hoc Bonferroni test and the level of significance was set at P < 0.0028 and P < 0.0013, respectively. Compilation of data and calculation of descriptive statistics were performed with SPSS for Windows (version 17.0).

Results

Referring doctor

A total of 10,260 new patients presented to the internal medicine departments of Chiba University Hospital during the study period. Among these patients, 1,402 presented to the General Medicine Department and 408 (29.1%) of them were referred to us without diagnosis. Among these 408 patients, 169 (41.4%) were referred by general physicians and 239 (58.6%) were referred by other physicians (Table 1).

Demographics and duration of symptoms of the patients referred for diagnosis

The 169 patients who were referred by general physicians included 60 men (35.5%) and 109 women (64.5%). Their median age was 52 years (range: 16-86 years), and the median interval from the onset of symptoms until referral to our department was 60 days (range:1-3650 days). These results were similar to those for the patients referred by other physicians (Table 2).

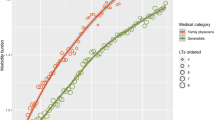

Final diagnosis

When the final diagnosis was classified by organ system according to ICPC-2, patients referred by general physicians most commonly had “General & Unspecified” conditions (35 patients, 20.7%), followed by “Psychological” conditions in 31 patients (18.3%), “Musculoskeletal” conditions in 21 patients (12.4%), and “Digestive” conditions in 20 patients (11.8%). When the patients were analyzed according to the referring physician, the three common categories were the same, and there was no significant difference of each category between the two groups according to Fisher’s exact test with a post hoc Bonferroni test (Table 3).

Among final diagnoses in the category of “General & Unspecified” conditions for patients referred by general physicians, 9 patients had unspecified viral infections, 8 patients were found to be normal, and 8 patients had adverse reactions to medications. Among the patients who were diagnosed as actually being normal, the main complaint was low-grade fever in 4 patients who were concerned about serious diseases and had no abnormalities on testing. Their symptoms improved after they were reassured that there were no abnormalities. “Psychological” conditions included anxiety disorder in 9 patients, mood disorder in 6 patients, adjustment disorder in 5 patients, and somatoform disorder in 4 patients. In two patients, a final diagnosis could not be made. Both were referred to our department with fever of unknown origin. One patient failed to return for further assessment and 1 patient improved spontaneously. Among the patients referred by other physicians, 19 patients had somatoform disorder, and there was no significant difference of each disease between the two groups according to Fisher’s test with a post hoc Bonferroni test (Table 4).

Specialist treatment and hospitalization after diagnosis

While 107 patients (63.3%) completed treatment at the General Medicine Department, 44 patients (26.0%) were referred to specialist departments of our hospital for further evaluation and treatment (Table 5). Among the patients referred by general physicians only four patients (2.4%) were admitted to hospital, which was a significantly lower rate than that for the patients referred by other physicians (P = 0.002) (Table 6). Their diagnoses included microscopic polyangitis, relapsing polychondritis, pneumonia, and purulent lymphadenitis in one patient each.

Discussion

In the present study, patients who were referred to a General Medicine Department because of difficulty in making a diagnosis had symptoms for 2 months on average. This suggests that a general outpatient department is likely to attract patients who have chronic diseases that do not require hospitalization but are difficult to diagnose and need to be investigated while considering a wide range of possibilities. We will discuss the characteristics of the diseases involved and the reasons for referral of these patients to the General Medicine Department by general physicians.

Classification of the final diagnoses of the patients general physicians referred to the General Medicine Department by organ system according to ICPC-2 revealed that “General & Unspecified” conditions was the most frequent diagnostic category, among which the most frequent diagnoses were normality, unspecified viral infections, and adverse reactions to medications. Patients who are actually normal and those with unspecified viral infections are unlikely to have any specific findings, so diagnosis often involves excluding a wide range of diseases. According to a report from Australia, adverse reactions to medications were detected in 10% of patients consulting general practitioners over a 6-month period, and the incidence was especially high among elderly patients [10]. Physicians should keep this in mind when making a differential diagnosis, since adverse reactions can be improved by discontinuing/switching the causative drug. In general, patients with benign diseases such as viral infections have nonspecific symptoms at an early stage, so that primary care physicians often need time to make a diagnosis. However, Japanese patients have a preference for attending large hospital because of accessibility, so patients and/or family members might request referral to a university hospital before their general physicians can make a diagnosis [11].

“Psychological” conditions was the second most frequent category. A possible reason for this high frequency of “Psychological” conditions may be that patients with psychological problems often consult general physicians or specialist departments other than the Department of Psychiatry while complaining of physical symptoms. It has been reported that patients with depression and anxiety disorders diagnosed at primary care clinics often only complain of physical symptoms [12],[13]. Thus, patients with psychiatric diseases who present with physical symptoms may frequently be referred to a general outpatient department since their underlying diseases cannot be identified by investigations for organic illnesses. In addition, it was reported that patients with neurological diseases (such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer disease, or cerebrovascular disease), infections (such as human immunodeficiency virus), endocrine/metabolic diseases, cancer, and collagen diseases have a high frequency of mood disorder [14],[15]. This adds another layer of difficulty to the diagnosis of psychological diseases because physicians have to consider the possible coexistence of a wide range of organic diseases.

Among “Musculoskeletal” conditions, which was the third major category, polymyalgia rheumatica and connective tissue diseases can be difficult to diagnose, but common diseases such as cervical spondylosis were also missed. In Western countries, it is estimated that approximately 20% of patients attending primary care clinics complain of musculoskeletal symptoms. [16],[17] In Japan, Tanaka reviewed several nationwide studies of the symptoms and diseases handled by primary care clinics, and reported that diseases related to pain and arthritis were always frequent, indicating that primary care physicians need to have sufficient knowledge and skill in the orthopedic field [9].

The types of patients under management and the specialty fields differ between general physicians and other physicians, suggesting that the diseases these doctors find difficult to diagnose might also differ. A comparison between referrals from general physicians and referrals from other physicians showed that the frequency of “Psychological” conditions (especially somatoform disorder) were somewhat more frequent among patients referred by other physicians, suggesting that specialists also have difficulty in diagnosing patients with various symptoms and no abnormalities related to their specialties, in whom it is necessary to exclude diseases from other fields. However, the categories of “Psychological,” “General & Unspecified,” and “Musculoskeletal” conditions were common in both groups, and no significant differences were found. In Japan, there is no national recognition of general practitioners, unlike the United Kingdom and many other countries. It seems that some specialists who formerly worked in Japanese hospitals are now providing primary care as general physicians without having received psychiatric and orthopedic training. This suggests that, even though the clinical setting differs somewhat between general physicians and other physicians, both group encounter difficulty with a similar range of diagnoses.

In the present study, very few of the patients referred by general physicians needed hospitalization and only 30% needed specialist referral. Thus, Japanese general physicians have difficulty in diagnosing mild conditions that require exclusion of a wide range of diseases. A questionnaire study of Japanese and American residents revealed that Japanese clinical training was predominantly focused on inpatients [18]. It was also reported that Japanese general physicians want more outpatient training rather than inpatient training in order to improve their clinical skills for primary care [19]. To improve the diagnostic performance of physicians, further education at outpatient departments and clinics is required. It is also possible that general physicians do not perform an adequate gatekeeper role in Japan and tend to refer patients who have mild diseases to large hospitals because of the preference of Japanese patients for these institutions and the free access provided by the national health system. The Japanese government has tried to address the issue of undifferentiated functions among different tiers of health care facilities. Since 1996, patients who visit a large hospital without referral have had to pay an additional charge, but the fee (about 3000 to 4000 yen) may not be high enough to deter patients from spontaneously presenting to large hospital [7],[20]. Further development of a system to distinguish the function of clinics from those of hospitals by the government may be needed.

Limitations

Because this study was conducted at a single outpatient department, it is unclear whether the findings are widely applicable to Japanese general physicians elsewhere. Also, other factors that might influence referral, such as the patient’s preference, underlying mental condition, or relationship with the referring doctor need to be investigated in future studies.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that Japanese general physicians found it difficult to diagnose “Psychological” and “Musculoskeletal” disorders in daily practice, as well as variations within the normal range and viral infections. Since most of these conditions referred by general physicians do not require hospitalization, appropriate education at outpatient departments and clinics will be required to improve diagnostic performance among general physicians in Japan. It is also important to enhance the gatekeeper role of Japanese general physicians and to develop a healthcare system that more clearly demarcates the functions of clinics and hospitals.

References

Ikegami N, Campbell JC: Health care reform in Japan: the virtues of muddling through. Health Aff 1999, 18: 56–75. 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.56

Koizumi S: The need of general internal medicine: its historical and social background. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 2003, 92: 2319–2325. 10.2169/naika.92.2319

Ferrer RH, Hambidge SJ, Maly RC: The essential role of generalists in health systems. Ann Intern Med 2005, 142: 691–699. 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00037

Green C, Holden J: Diagnostic uncertainty in general practice. A unique opportunity for research? Eur J Gen Pract 2003, 9: 13–15. 10.3109/13814780309160388

Knottnerus JA: Medical decision making by general practitioners and specialists. Fam Pract 1991, 8: 305–307. 10.1093/fampra/8.4.305

Ikegami N, Campbell JC: Medical care in Japan. N Engl J Med 1995, 333: 1295–1299. 10.1056/NEJM199511093331922

Ito M: Health insurance systems in Japan: a neurosurgeon’s view. Neurol Med Chir 2004, 44: 617–628. 10.2176/nmc.44.617

Yamada T, Yoshimura M, Nagou N, Asai Y, Koga Y, Inoue Y, Hamasaki K, Mise J, Lamberts H, Okkes I: What are the common diseases and common health problems? The use of ICPC in the community-based project. Jap J Prim Care 2000, 23: 80–89.

Tanaka K, Nomaguchi S, Matsumura S, Fukuhara S: Ranking the frequency of patient illness at primary care clinics. Jap J Prim Care 2007, 30: 344–351.

Miller GC, Britt HC, Valenti L: Adverse drug events in general practice patients in Australia. Med J Aust 2006, 184: 321–324.

Sugisawa H, Nishi S: Factors related to choice of medical facilities by residents. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 1995, 42: 463–471. (in Japanese)

Simon GE, Vonkorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J: An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Eng J Med 1999, 341: 1329–1335. 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801

Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA: The association between anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms in a large population: the Hunt-II study. Psychosom Med 2004, 66: 845–851. 10.1097/01.psy.0000145823.85658.0c

Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden RN, Gorman JM, Krishnan KR, Nemeroff CB, Bremner JD, Carney RM, Coyne JC, Delong MR, Frasure-Smith N, Glassman AH, Gold PW, Grant I, Gwyther L, Ironson G, Johnson RL, Kanner AM, Katon WJ, Kaufmann PG, Keefe FJ, Ketter T, Laughren TP, Leserman J, Lyketsos CG, McDonald WM, McEwen BS, Miller AH, Musselman D, et al.: Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry 2005, 58: 175–189. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001

Chida Y: Depression and physical disease. Jpn J Clin Psychiatry 2006, 35: 927–933. (in Japanese)

Rekola KE, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Takala J: Use of primary health services in sparsely populated country districts by patients with musculoskeletal symptoms: consultations with a physician. J Epidemiol Community Health 1993, 47: 153–157. 10.1136/jech.47.2.153

Busato A, Dönges A, Herren S, Widmer M, Marian F: Health status and health care utilization of patients in complementary and conventional primary care in Switzerland-an observational study. Fam Pract 2005, 23: 116–124. 10.1093/fampra/cmi078

Fetters M, Kitamura K, Mise J, Newton W, Gorenflo D, Tsuda T, Igarashi M: Japanese and United States family medicine resident physicians’ attitudes about training. Gen Med 2002, 3: 9–16. 10.14442/general2000.3.9

Kiyota A, Kamegai M, Sugimori H, Ishii A, Hayashi J, Hamashima C, Sunaga T, Ikusaka M, Yosida K, Nakamura T: Practice and education in the required clinical skills for primary care. Jap J Fam Pract 2002, 9: 13–21.

Ikegami N, Campbell JC: Japan’s health care system: containing costs and attempting reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004, 23: 26–36. 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.26

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TT carried out data collection, participated in the design of the study, and performed the statistical analysis. OY, KN, TT, and TU helped with data collection and statistical analysis. MI participated in study design and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsukamoto, T., Ohira, Y., Noda, K. et al. Investigation of diseases that cause diagnostic difficulty for Japanese general physicians. Asia Pac Fam Med 13, 9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12930-014-0009-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12930-014-0009-9