Abstract

Thyroid hormone analogues—particularly, l-thyroxine (T4) has been shown to be relevant to the functions of a variety of cancers. Integrin αvβ3 is a plasma membrane structural protein linked to signal transduction pathways that are critical to cancer cell proliferation and metastasis. Thyroid hormones, T4 and to a less extend T3 bind cell surface integrin αvβ3, to stimulate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathway to stimulate cancer cell growth. Thyroid hormone analogues also engage in crosstalk with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-Ras pathway. EGFR signal generation and, downstream, transduction of Ras/Raf pathway signals contribute importantly to tumor cell progression. Mutated Ras oncogenes contribute to chemoresistance in colorectal carcinoma (CRC); chemoresistance may depend in part on the activity of ERK1/2 pathway. In this review, we evaluate the contribution of thyroxine interacting with integrin αvβ3 and crosstalking with EGFR/Ras signaling pathway non-genomically in CRC proliferation. Tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac), the deaminated analogue of T4, and its nano-derivative, NDAT, have anticancer functions, with effectiveness against CRC and other tumors. In Ras-mutant CRC cells, tetrac derivatives may overcome chemoresistance to other drugs via actions initiated at integrin αvβ3 and involving, downstream, the EGFR-Ras signaling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide and studies of CRC understandably attract much attention in the oncology literature [108]. New therapeutic targets in the tumors and expanded anticancer drug choices have importantly transformed treatment strategies for CRC in recent years. Improved patient outcomes have resulted over the past two decades [12, 113]. Improvements in surgical techniques for managing the oligometastatic disease of lungs and liver in CRC have also contributed to improved overall survival (OS) of CRC patients. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) has increased CRC OS from 14.2 to nearly 30 months when combined with folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin (FOLFOX)- and folinic acid, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI)-based chemotherapies [53]. However, this improvement has not increased the 5-year survival rate for patients with Stage IV disease; the rate remains at < 15%, and metastatic CRC (mCRC) remains essentially incurable [103].

Among the new therapeutic targets in mCRC that appear to have promising effects are Ras isoforms. Ras genes are the most frequently mutated family of oncogenes in cancer. CRCs often contain mutant Ras proteins and these appear to be linked to chemoresistance. However, most Ras-specific targeted therapeutic strategies have to-date been unsuccessful [11]. No K-Ras-specific drugs have been approved for clinical use, although AMG510 is a therapeutic option for patients with KRAS G12C mutations [101]. New therapeutic approaches are needed for Ras-mutant CRC. Studies from our group and others indicate that cell surface integrin αvβ3 may play important role in regulation of CRC proliferation, especially under influence of thyroid hormones [26, 64, 69, 88]. Signaling induced by thyroid hormone via integrin αvβ3 may be involve crosstalk with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-Ras and contribute to the development of CRCs.

Integrin αvβ3 signal and genomic actions of thyroid hormone in CRC

Traditional genomic actions of thyroid hormone start with intranuclear binding of the hormone by nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) that are transcription factors [8]. In the genomic actions of thyroid hormone, T4 serves as a prohormone for T3 and the latter is the principal ligand of TR proteins. Triiodothyronine has a tenfold higher affinity than that of T4 for nuclear receptors [100]. The complex of TRβ with T3 translocates to the nuclear compartment where it sheds associated co-repressors, attracts co-activator proteins and becomes transcriptionally active. Although T4 involve in the initiation of this process of co-repressor releasing, it does not start the transcription[25]. Evidence indicates that traditional TRβ1-T3 plays negative role in cancer cell proliferation (Table 1) [64]. Table 1 lists a number of these overlapping genomic and nongenomic functions of thyroid hormone. On the other hand, the extracellular T4 or to a less extend T3 can, via a specific receptor on a plasma membrane integrin αvβ3, activate extracellular signal-regulated kinses (ERK1/2) and downstream signal transduction pathways to promote cell proliferation in variety types of cancer cells [6, 13, 33, 58, 71, 84].

The integrin αvβ3 is one of two dozen integrin heterodimers found on the surfaces of cells. While it has an important role in maintaining normal cell structure and in signal transduction, the integrin αvβ3 was shown to be over-expressed in high-growth endothelial cells and solid tumor and leukemic cells [9, 10, 23, 24, 26, 37, 42, 43, 64, 90]. Several small molecules (resveratrol[10], non-peptide hormones like steroid hormones [10] and thyroid hormones (T4, T3) have specific binding sites (receptors) on integrin αvβ3; at these sites, the ligands induce signal transduction and sequentially stimulate biological activities on cancer and endothelial cells [10]. These activities include cell proliferation [12, 20].

At physiological concentrations, thyroid hormone (T4) but not T3 [12, 20] initiates at the iodothyronine receptor on cell surface integrin αvβ3. As noted above, T4 via the integrin activates downstream ERK1/2, but the hormone, itself, does not enter the cell as a part of these functions. The consequences of signals generated at the integrin by T4 in cancer cells include cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis and radioresistance [12, 20], as discussed in the sections below. After interacting with T4, integrin αvβ3 is endocytosed into cytoplasm. Integrin monomeric αv, but not β3, translocates to the nucleus [70] and may function as a co-activator protein.

The interaction between thyroid hormone and integrin αvβ3 has been revealed by Davis’ group using computational modeling [65]. An arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) recognition site on the heterodimeric integrin αvβ3 is essential to the binding of a variety of extracellular matrix proteins. RGD peptides block the thyroid hormone binding site on integrin αvβ3 to inhibit and consequent ERK1/2 activation. These observations suggest that the hormone interaction site is located at or near the RGD recognition site on integrin αvβ3. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase that promotes cell migration and invasion through the control of focal adhesion turnover. Downstream of integrin αvβ3, FAK connects ERK1/2[104], PI3K/AKT[77], and other signal transduction pathways.

Thyroid hormone binds to integrin αvβ3 to promote cancer proliferation

At physiological concentration, T4, but not T3, interacts with integrin αvβ3 to induce integrin αvβ3 to translocate into cytosol without T4 companion [70]. Several studies indicate that there are multi-mechanisms regulating integrin internalization [27]. Integrin αvβ3 has been shown to be internalized through caveolin-dependent mechanisms [35]. A possible mechanism is that endocytosed integrin αvβ3 is phosphorylated and binds with caveolin during endocytosis [117]. Sequentially, integrin β3 disassociates from complex, and the integrin α/caveolin complex binds with phosphorylated ERK1/2 [55]. The activated integrin αv-ERK1/2 complex translocates into nucleus and regulates transcriptional activities via binding to other transcription factors [120]. T4 induces nuclear integrin αv-ERK1/2-complex further associates with transcriptional coactivators, p300 and STAT1, and with corepressors, NCoR and SMRT[70]. The complexed phosphorylated ERK1/2 may be response to phosphorylation of coactivators [82] and corepressors [25]. Phosphorylation activates functional co-activators and repressors. The complex binds promotors of responsible genes including estrogen receptor-α, cyclooxygenase-2, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, and thyroid hormone receptor β1. Those genes are important for cancer cell biological activities (Fig. 1). However, other mechanisms may also involve in thyroxine-integrin αvβ3 signal transduction pathway.

Thyroxine and Triiodothronine induce gene expression via different pathways. Thyroid hormone (T4) binds with integrin αvβ3 to induce integrin αvβ3 endocytosis without T4 bound. The integrin αvβ3 in cytoplasma associates with activated ERK1/2. The integrin αv monmer-pERK1/2 translocates into the nucleus and forms transcriptional complex with p300 and pSTAT3 which releases co-repressors, NCoR and SMRT from promotor region. The integrin αv-pERK-STAT3-p300 complex plays a co-activator function. On the other hand, T4 can also penetrate cell membrane via active transporters, and converted to T3 by deiodinase (D1 or D2). T3 binds to TRβ1, and the consequences are normal thyroid hormone-dependent biological activities which also show anti-proliferative effect in cancer cells

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is an evolutionarily conserved cell signaling system that mediates key physiological processes but is also incriminated in the occurrence of several malignant neoplasms, including colon cancer. Thyroid hormone has been shown to promote the nuclear accumulation of HMGA2 and β-catenin in a concentration-dependent manner in colorectal cancer cells with different k-RAS statuses [61]. A dense collagen matrix increases integrin-mediated cell-ECM interactions with phosphorylated FAK and ERK signaling to exhibit a disrupted membranous E-cadherin/β-catenin complex and, remarkably, show cytoplasmic or nucleic localization of β-catenin, sequentially to regulate cell proliferation in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells [46]. Furthermore, membranous E-cadherin/β-catenin complex could be recovered by inhibiting the phosphorylation of FAK [46]. The nucleus- accumulated β-catenin induces Cyclin D1 and c-Myc [58], the downstream targets of the β-catenin pathway, are also strongly correlated with cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in colorectal cancer[107].

Additionally, T4 induces PD-L1 expression in human breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and oral cancer cells [62, 72]. Recently, our studies have shown that thyroid hormone increases cytosolic and nuclear PD-L1 accumulation[10] which may be anti-apoptotic [63]. Expression of PD-L1 is regulated via activated ERK1/2 and PI3K [45, 62]. Thyroid hormone-induced PD-L1 is involved in CRC proliferation[45]. Blockage of thyroid hormone binding with integrin αvβ3 can inhibit PD-L1 expression and cell proliferation in CRC cells [45]. On the other hand, inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is able to reduce PD-L1 expression and CRC proliferation in K-Ras wild type but not K-Ras mutant CRC cells[45]. These studies further demonstrate that thyroid hormone-activated signal via integrin αvβ3 also cross-talks with the EGFR signal to modulate cancer cell proliferation[5].

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in CRC cells

The structural domains of EGFRs include an extracellular ligand-binding component, a transmembrane component, and an intracellular tyrosine kinase feature. The EGFR is activated upon binding with ligands such as EGF, transforming growth factor (TGF)-α, amphiregulin, heparin-binding EGF, and betacellulin [41]. After being bound with ligands, EGFR dimerizes, auto-phosphorylates, and consequently activates the tyrosine kinase component of EGFR [91]. Ultimately, EGFR signaling has positive downstream effects in terms of increased cell proliferation and improved cell survival. The EGFR pathway contributes importantly to cell differentiation, as well as proliferation. A dearth of EGFR activity results in the developmental failure of multiple organs.

Overexpressed EGFRs exist in many primary cancers including CRC, and play important roles in both tumor growth and progression [56]. Expression or upregulation of the EGFR gene was demonstrated in up to 80% of CRC cases [85, 99]. Regular EGFR activity is also crucial for the formation of tumors in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-mediated intestinal tumorigenesis [110]. Essentially, EGFRs’ signaling is able to accelerate proliferation, survival, invasion, and immune evasion in CRC cells [12]. Consequently, there is also a metastatic risk [81]. EGFR signaling pathway can regulate migration and invasion through β-catenin activity. Additionally, tumor cells with a low EGFR expression have low tumor metastatic risk and better survival rates in CRC patients [44].

Main EGFR downstream effectors are molecules involved in the Ras-Raf-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)/MAPK pathway. EGF binds to EGFR to promote activation downstream of Ras signaling[118]. Binding to their plasma membrane receptors, growth factors may activate receptor-linked tyrosine kinases (RTKs), leading to activation of Son Of Sevenless (SOS), a Ras-selective guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RasGEF) that supports nucleotide exchange, and an activated conformation of Ras-GTP. When activated, the Ras-GTP complex attaches to a variety of effector proteins involved in downstream signaling and consequent cell growth/survival, differentiation, and both migration and adhesion. Downregulation of the EGFR signaling pathway should, therefore, result in interruption of this pathway and ultimately in reduced cellular proliferation.

Mutations of K-Ras, such as G12C, are found in most of pancreatic cancers, and one-third of lung cancers, and 50% of CRCs; these mutations are associated with high mortality rates. Accumulations of abnormal APC, K-Ras, and β-catenin genes are early events in CRC tumorigenesis [15, 60]. However, any correlations that exist among these events are still unclear. EGFR signaling is able to crosstalk with the Wnt-β-catenin pathway to stimulate CRC growth and can trigger β-catenin signals via the receptor tyrosine kinase-PI3K/Akt pathway, while β-catenin can stimulate EGFR signaling via the transmembrane Frizzled receptor [2, 106]. Furthermore, the EGFR signal can crosstalk with β-catenin to promote frequencies of invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells [2]. EGF-induced nuclear localization of SHC Binding and Spindle Associated 1 (SHCBP1) activates β-catenin signaling by enhancing the CBP/β-catenin interaction [73] and promotes cancer progression [73]. EGFR activation is partly due to α2,6 sialylation of the EGFR by ST6Gal1, which affects EGF-induced cancer cell proliferation [96]. Additionally, ST6Gal1-induced α2,6 sialylation is critical for adhesion and migration of CRC cells [96]. ST6Gal1 induces mutant EGFR sialylation in CRC HCT116 cells [5]. The anticancer activity of gefitinib is more significant in ST6Gal1-deficient CRC cells, as over-expressed ST6Gal1 was shown to suppress gefitinib-induced cytotoxic effects and promote gefitinib-mediated chemoresistance in CRC cells [5].

Crosstalk between integrin αvβ3 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in CRC cells

Thyroid hormone regulates K-Ras expression [40]. The hormone significantly enhances expression of PCNA, Cyclin D1, and c-Myc and their protein levels in both K-Ras wild type HT-29 and mutant HCT 116 cells [59]. The T4 antagonist and derivative of tetrac, nano-diaminotetrac (NDAT), and cetuximab significantly suppress transcription of cell proliferation-associated genes; these include PCNA, Cyclin D1, c-Myc, and RRM2 induced by thyroxine; these effects are significantly enhanced over cetuximab, alone, in HCT 116 cells. In addition, T4 suppression of transcription of mRNAs of pro-apoptotic genes p53 and RRM2B is significantly antagonized by the combination of NDAT and cetuximab compared to cetuximab alone [59]. In K-Ras mutant HCT 116 cells, but not in the K-Ras wild type COLO 205 cells, the combinations of tetrac/NDAT and cetuximab significantly reduced cell proliferation compared to cetuximab, alone. In summary, T4 promotes CRC cell proliferation and this action is opposed by tetrac and NDAT. The combination of tetrac/NDAT and cetuximab potentiates cetuximab actions in K-Ras mutant colorectal cancer cells [59]. These results suggest indicated existence of crosstalk between thyroid hormone and the EGFR-K-Ras signal pathway in CRC.

Therapies based on targeting EGFR signaling in CRC

EGFR-targeted therapies have been of particular interest because of the clinical benefits conferred by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to the receptor, such as panitumumab and cetuximab, and identification of biomarkers that inform treatment decision-making [50]. Genetic heterogeneity in CRC, however, often conveys a need for personalized chemotherapeutic protocols. Genetic variations may make difficult the full characterization of resistance mechanisms in standard therapies [116]. K-Ras has been the subject of extensive drug-targeting endeavors over the past three to four decades. These endeavors include targeting the K-Ras protein itself, as well as its posttranslational modifications, membrane localization, protein–protein interactions, and downstream signaling pathways. Despite optimized patient selection based on Ras mutation status, the primary and secondary resistance to mAbs is still higher than desired [50].

Using molecular targeted drugs, such as bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, aflibercept, and regorafenib, can increase clinical survival rates [79, 102]. Although new chemotherapeutic regimens have improved patient responses, their use remains limited by inherent chemoresistance of tumors and the acquisition of resistance in the course of therapy [103, 113]. However, anti-EGFR therapies are often affected by tumor cell mutation associated with resistance based on alterations in EGFR-driven signaling systems [113].

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been extensively investigated for CRC treatment. Cetuximab and panitumumab are mAbs that inhibit activities of EGFR through blocking the binding of EGF to EGFR, including downstream signaling that is initiated at the receptor. Such signaling pathways include Ras-Raf-MEK-MAPK, phosphatase, and tensin homolog (PTEN) and the phosphatidylinositol-AKT pathways [12, 34, 83]. Panitumumab and cetuximab both are in clinical use for CRC [97, 122]. Cetuximab (Erbitux®) is a chimeric [immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1)] mAb. When bound to the extracellular domain of the EGFR, cetuximab can block endogenous ligand binding and inhibit proliferation of cancer cells. Cetuximab may also have immune-regulated anticancer effects, for example, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity [83]. In a Phase II clinical trial, cetuximab improved survival and reversed chemoresistance in patients with refractory mCRC [16], a result that led to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the drug for management of metastatic CRC. In addition to improving the survival rate, cetuximab maintains the quality of life for mCRC patients [49]. Cetuximab is administered intravenously after initial biweekly or weekly loading dosage and used as a solo agent in the setting of mCRC or in conjunction with a second standard chemotherapeutic agent [78]. A humanized IgG2 EGFR antibody, panitumumab is bound by the EGFR extracellular domain and interrupts signaling for ligand-mediated proliferation. The efficacy of panitumumab was shown to result in clinical benefits both when added to chemotherapy and as monotherapy in mCRC in various clinical settings [1, 29].

The most likely basis for resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in cancer cells is constitutive activation of signaling pathways linked to EGFR and this may or may not be a function of constitutive EGFR activity. The principal predictors of cetuximab failure are point mutations of the KRAS gene, principally in codon 12 or 13 in exon 2 [3, 92]. Functionally, this means that cetuximab monotherapy or conjunctive therapy is to be used in mCRC patients whose tumors bear wild-type (WT) K-ras. After treatment with cetuximab, however, biochemical convergence may occur in tumor cells to reactivate the Ras-Raf-MEK-MAPK signaling pathway [113, 114].

Another EGFR-targeted therapy involves TKIs. TKIs are small molecules derived from quinazolines that can be transported across cell membranes and block the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of various receptors such as EGFR, Erb2, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) [123]. Gefitinib (Iressa®) is an EGFR specific antagonist that can block the phosphorylation of the EGFR [47]. It also can target other pathways such as ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mesothelioma cell lines [32]. Gefitinib is used to treat non-small cell lung cancer and various types of cancers as a single agent or in combination with other anticancer agents [7]. It is only used for phase II clinical trial in CRC in Europe [4]. Erlotinib is a specific inhibitor of the EGFR that can also block phosphorylation of the ligand-induced EGFR. Both of these drugs have been highly effective in other tumor types, particularly lung cancer harboring mutations of the EGFR gene [86]. As such, there has been great interest in determining the efficacy of EGFR TKIs in mCRC.

Gefitinib-inhibited EGFR activity results in EGFR dephosphorylation, HER3-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complex dissociation, and a decrease in Akt activity [93]. Plasma membrane integrins, ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase protein), and EGFR have been shown to contribute to fibronectin (FN) induction by the activation of ERK1/2, p38, and Akt. These agents also are involved in promoting growth and invasiveness of cancer cells. Gefitinib prevents FN-induced signal molecule activation and other activities in hepatocellular carcinoma CBO140C12 cells, suggesting that activation of EGFR tyrosine kinase regulates these FN responses [80]. Thus, a gefitinib-induced anti-metastatic activity involves blockage of FN-induced signaling [80]. Gefitinib inhibits activation of Akt and ERK [7] by disturbing the K-Ras/PI3K and K-Ras/Raf complexes to reduce synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). However, constitutive activation of PI3K or ERK1/2 signal transduction pathways is involved in gefitinib-induced resistance in cancers. Gefitinib disrupts K-Ras/PI3K and K-Ras/Raf complexes in human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Calu3 cells but not in K-Ras-mutant Calu3ras cells [7, 30]. The K-Ras mutation was correlated with gefitinib resistance [95]. Gefitinib combined with lovastatin downregulates the K-Ras protein and can effectively suppress EGFR phosphorylation and activation of Raf, ERK1/2, and Akt in gefitinib-resistant human NSCLC A549 and NCI-H460 cells [7]. EGFR mutations can also affect the sensitivity of CRCs to gefitinib, but this effect is not consistent [125]. Gefitinib was shown to inhibit human chondrosarcoma proliferation and metastasis by inducing cell cycle arrest, leading to a decrease in the migration capacity [109]. Gefitinib also reduces expressions of metastasis-related proteins, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and MMP-2 and MMP-9 [109]. Gefitinib has been combined with other cancer chemotherapeutic agents to manage various cancers [36, 52, 111, 112]. What is clear is that gefitinib affects a number of therapeutic targets in cancer cells mentioned above, yet resistance to this TKI does develop [76]. In this review article, we describe a new treatment strategy that restores responsiveness to gefitinib.

In addition, immunotherapies have been applied in current mCRC studies against other targets. These include use of antibodies that target the VEGF/VEGFR pathway [Bevacizumab (Avastin®), and Ramucirumab (Cyramza®)]. Alternatively, immunotherapy may use checkpoint PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors such as Nivolumab (Opdivo®) and Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®).

Tetrac derivatives compete with thyroid hormone to bind on integrin αvβ3

Tetrac derivatives compete with T4 for the iodothyronine receptor on the integrin αvβ3 [5]. NDAT acts primarily at the cell surface receptor and does not enter the nucleus when internalized by tumor cells. In contrast, tetrac may undergo nuclear uptake and, in the nuclear compartment, tetrac has low-grade thyrometic activity, rather than anti-thyroid (anti-T4) effects. Tetrac derivatives block binding of T4 to the cell surface thyroid hormone receptor on integrin αvβ3; they thereby inhibit the non-genomic effects of thyroid hormone-initiated downstream signal transduction pathways [5, 59, 64, 72, 90]. The interaction between tetrac derivatives and integrin αvβ3 regulates gene expression related to cancer cell survival pathways, for example, pathways that oppose induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. Tetrac derivatives also downregulate cancer cell proliferation via integrin αvβ3 in the absence of T4 [64].

Tetrac and NDAT also support apoptosis and suppress angiogenesis by differentially modulating transcription of a panel of genes linked to these processes[19]. Both tetrac and NDAT upregulate expressions of the proapoptotic BcL-x short form [38], the antiangiogenic thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), and other proapoptotic genes [64]. In addition, they suppress transcription of several anti-apoptotic gene families. Catenin proteins play roles in cell–cell adhesion, and β-catenin also has transcriptional functions in the nucleus. Mutation and overexpression of β-catenin occur in a variety of cancers, including CRC and breast and ovarian cancers [51, 119]. Tetrac and NDAT increase transcription of the CBY1 gene which codes for an inhibitor of β-catenin [89]. Tetrac and NDAT also reduce β-catenin abundance via downregulation of the CTNNA1 and CTNNA2 genes [19]. While the function of CTNNA1 protein may include suppression of invasiveness of tumor cells [115], mutated CTNNA1 may be involved in induction of GI tract cancer [28]. Mutated CTNNA2 is linked to tumor invasion [31]. At the tumor cell surface thyroid hormone analogue receptor on integrin αvβ3, tetrac inhibits the pro-angiogenic activities of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [18]. NDAT inhibits transcription of anti-apoptotic factors such as myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (MCL1) and XIAP. NDAT acts differentially, however, to upregulate expression of apoptosis-inducing genes such as caspase-2(CASP2), BCL2L14, and BAD [19]. NDAT also blocks transcription of the Ras-oncogene family [19]. The expression of cyclin genes is also downregulated in cancer cells by NDAT [38]. Interestingly, our studies also indicated both tetrac and NDAT are able to inhibit programmed cell death/ligand 1 PD-L1 expression and protein accumulation by cancer cells [59]. Production of PD-L1 blocks host immune T cells from attacking the tumor cells. The anti-PD-L1 activities of tetrac and NDAT could potentially be a new therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy. NDAT inhibits expression of ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2 (RRM2) that is caused by the stilbene, resveratrol but potentiates resveratrol’s anticancer activity [90]. In summary, tetrac derivatives regulate expression of genes involved in modulating angiogenesis and regulating tumor cell metabolism by multiple mechanisms [21]. In addition to antiproliferation, tetrac and NDAT were shown to augment other drug-induced anticancer growth [65, 89, 91, 103]. The effects of tetrac derivatives are summarized in Table 2.

Combined treatment of tetrac derivatives and anticancer agents

Treatment with tetrac and NDAT is not cytotoxic to nonmalignant cells [19] or in animal studies [5, 90]. We have studied in several cell models the combined treatment effects of tetrac or NDAT as well as other anticancer drugs in CRC cells [5, 59, 68, 89] and other cancer cells [68].

Gefitinib has been shown to be less effective in CRC compared to other cancer types [4]. Compared to results in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, CRC patients required a higher dosage of drug to achieve stale disease, and the latter was not associated with reduction in tumor size [4]. Cellular studies indicated that atorvastatin (5 μM) enhanced cytotoxicity of gefitinib-related inhibition of Akt and ERK activity [7]. Cytotoxicity can be additive in combination therapy.

Functional sialylation of β-galactoside α-2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6Gal1) on the EGFR was highly correlated with CRC progression and metastasis [96]. Upregulation of α2,6-sialylation may also induce radioresistance in CRC [96]. Other studies have shown that gefitinib is more effective in ST6Gal1-knockdown CRC SW480 cells [96]. Our investigation has shown that ST6Gal1 induces sialylation of mutant EGFRs in CRC HCT116 cells [5]. Interestingly, gefitinib increased antiproliferation in ST6Gal1-deficient CRC cells [5]. In contrast, ST6Gal1 overexpression decreased the cytotoxic effect of gefitinib [96]. Sialylation of the EGFR by ST6Gal produced gefitinib chemoresistance in CRC cells [96]. EGFR sialylation affected EGF-mediated cancer cell proliferation [96]. On the other hand, sialylation promoted gefitinib resistance in CRC cells [5]. NDAT reduced ST6Gal1 expression and inhibited CRC cell proliferation [5]. NDAT enhanced gefitinib-induced antiproliferation via a mechanism involving inhibition of ST6Gal1 activity and PI3K activation [5].

Cetuximab (Erbitux®) inhibited K-Ras WT cells, but not K-Ras-mutant CRC cell growth [59]. Tetrac significantly enhanced cetuximab-reduced cell proliferation in K-Ras-mutant HCT 116 cells, but not in K-Ras WT COLO 205 cells [59]. However, NDAT potentiated cetuximab-induced antiproliferation in both K-Ras WT and K-Ras-mutant CRC cells [59]. Gefitinib blocks Akt and ERK activities [7] by disturbing the K-Ras/PI3K and K-Ras/Raf complexes to reduce synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [112]. Gefitinib (1 μM) did not inhibit PI3K activation in HCT116 cells, although gefitinib inhibited the complexing of K-Ras/PI3K and K-Ras/Raf in NSCLC K-Ras/PTEN or K-Ras/PIK3CA co-mutant cells [7]. Consistent activation of the PI3K/Akt and/or Ras/ERK pathways was associated with gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cell lines [48].

In addition to reducing ST6Gal1 expression, NDAT blocks EGFR sialylation by ST6Gal1 and consequent PI3K activation [5]. When intact—in the absence of NDAT—both reactions contribute to proliferation in K-Ras WT and K-Ras mutant cells [81]. The combination of NDAT and gefitinib in CRC cell lines permitted efficient identification of pro-apoptotic and metastasis-relevant genes affected by the drugs [81]. NDAT differentially regulates the expression of specific genes at integrin αvβ3 [19, 20, 38, 64] and the consequences of NDAT action are cell cycle disruption, apoptosis, and anti-angiogenesis [20]. Other studies of HCT116 CRC xenograft-bearing mice have also demonstrated that NDAT additively promotes gefitinib-induced anticancer activity [5]. While downregulation of ST6Gal1 transcription has been shown to stimulate tumor cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo [96], NDAT demonstrated its capability to decrease ST6Gal1 expression and CRC growth. Although decreased ST6Gal1 may increase EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation and ERK1/2 activation in CRC cells [96], NDAT has been shown to reduce ERK1/2 activation and ST6Gal1 accumulation in CRC cells [5]. In addition, NDAT suppressed PI3K activation to down-regulate PD-L1 expression and protein accumulation in vitro and in xenograft in K-Ras-mutant CRC [45]. Gefitinib effectively reduces cancer metastasis by downregulating expressions of metastasis-linked proteins, e.g., MMP-9, MMP-2, and bFGF [109]. In contrast. NDAT can inhibit expressions of MMP-2, MMP-9, and VEGF-A [19, 64, 66] and further enhance inhibitory effects on MMP-2, MMP-9, and VEGF-A by gefitinib.

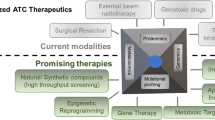

Tetrac derivative actions in cells exhibit potential for the clinical treatment of K-Ras-mutant CRC patients. Our studies indicate that NDAT has greater therapeutic potential than tetrac since it can reverse K-Ras-mutant-dependent resistance using cetuximab and gefitinib. However, xenograft weights in animals treated via NDAT alone did not significantly decrease compared to those in the untreated control [5, 90]. Therefore, NDAT alone or combined with a low dosage of cetuximab and gefitinib has new chemotherapeutic potential. Such observations show that added or enhanced effects can be obtained when tetrac derivatives are combined with other chemotherapeutic agents (Fig. 2).

Targeting Therapies of CRC is compensated by NDAT in K-Ras Mutant Colorectal Cancers. Thyroid hormone stimulates signal pathway of integrin αvβ3-FAK axis and proliferation. EGF via EGFR-Ras pathway promotes proliferation. It also cross-talks with integrin αvβ3 signal via FAK activation. These signals can induce activation of PI3K- and ERK1/2-dependent pathways. In addition, signals via growth factor receptors are also able to induce β-catenin-dependent cell proliferation. NDAT inhibits signal pathway of integrin αvβ3-FAK axis and proliferation. EGFR-dependent signal pathways via Ras-PI3K/ERK1/2 crosstalk with FAK. These signals can be intercepted by blocking activation of FAK, PI3K and ERK1/2. Crosstalk between growth factor receptors and FAK can be blocked by NDAT treatment

Conclusion

Thyroid hormone as T4, acting via cancer cell plasma membrane integrin αvβ3, induces cell proliferation, and metastasis. The hormone may engage in crosstalk with EGFR in modulating a variety of cancer cell activities. Targeting EGFRs by antibodies or by EGFR-specific TKIs has shown promising results in CRC therapies. However, both immunotherapy and targeting therapy in K-Ras-mutant CRC patients have raised concerns about resistance. Combined treatment with EGFR-specific inhibitor agents augments antitumor responses beyond initial single EGFR inhibitor therapy [124]. Multiple-agent treatments of cancers have been practiced for years, often achieving efficacy that exceeds single agents. Targeting cell surface integrin αvβ3, tetrac, and chemically-modified tetrac (NDAT) also inhibit the EGFR-dependent signal transduction pathway via crosstalk between the integrin and the EGF receptor. These agents can potentiate the antiproliferative actions of cetuximab and gefitinib in K-Ras-mutant CRC. Both gefitinib and NDAT inhibit proliferation in K-Ras WT CRC cells. While gefitinib is unable to suppress cell growth in K-Ras-mutant CRC cells, NDAT induces anti-proliferation by blocking ST6Gal1 activity and PI3K signal transduction. Although NDAT targets the integrin αvβ3 via crosstalk with EGFR signaling, NDAT enhances anti-proliferation induced by gefitinib in CRC cells. A similar observation was obtained with other EGFR blockers such as cetuximab [59]. Tetrac derivatives can overcome mutations in EGFR signal transduction pathways to potentiate cetuximab-induced antiproliferation in K-Ras-mutant CRC. Thus, use of NDAT—either alone or combined with other agents, such as gefitinib and cetuximab is a promising approach to treatment of human K-Ras-mutant CRC. A summary of the efficacy in cancer cells of currently available clinical agents and potential advantage of combination treatment with tetrac derivatives are listed in Table 3.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, Van Cutsem E, Siena S, Freeman DJ, Juan T, Sikorski R, Suggs S, Radinsky R, Patterson SD, Chang DD. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1626–34.

Barbolina MV, Burkhalter RJ, Stack MS. Diverse mechanisms for activation of Wnt signalling in the ovarian tumour microenvironment. Biochem J. 2011;437(1):1–12.

Bardelli A, Siena S. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to cetuximab and panitumumab in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1254–61.

Blanke CD. Gefitinib in colorectal cancer: if wishes were horses. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5446–9.

Chang TC, Chin YT, Nana AW, Wang SH, Liao YM, Chen YR, Shih YJ, Changou CA, Yang YS, Wang K, Whang-Peng J, Wang LS, Stain SC, Shih A, Lin HY, Wu CH, Davis PJ. Enhancement by nano-diamino-tetrac of antiproliferative action of gefitinib on colorectal cancer cells: mediation by EGFR sialylation and PI3K activation. Horm Cancer. 2018;9(6):420–32.

Chen C, Xie Z, Shen Y, Xia SF. The roles of thyroid and thyroid hormone in pancreas: physiology and pathology. Int J Endocrinol. 2018;2018:2861034.

Chen J, Bi H, Hou J, Zhang X, Zhang C, Yue L, Wen X, Liu D, Shi H, Yuan J, Liu J, Liu B. Atorvastatin overcomes gefitinib resistance in KRAS mutant human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e814.

Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):139–70.

Chin YT, He ZR, Chen CL, Chu HC, Ho Y, Su PY, Yang YSH, Wang K, Shih YJ, Chen YR, Pedersen JZ, Incerpi S, Nana AW, Tang HY, Lin HY, Mousa SA, Davis PJ, Whang-Peng J. Tetrac and NDAT induce Anti-proliferation via Integrin alphavbeta3 in Colorectal Cancers With different K-RAS status. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:130.

Chin YT, Wei PL, Ho Y, Nana AW, Changou CA, Chen YR, Yang YS, Hsieh MT, Hercbergs A, Davis PJ, Shih YJ, Lin HY. Thyroxine inhibits resveratrol-caused apoptosis by PD-L1 in ovarian cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(5):533–45.

Christensen JG, Olson P, Briere T, Wiel C, Bergo MO. Targeting Kras(g12c) -mutant cancer with a mutation-specific inhibitor. J Intern Med. 2020;288(2):183–91.

Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1160–74.

Cohen K, Flint N, Shalev S, Erez D, Baharal T, Davis PJ, Hercbergs A, Ellis M, Ashur-Fabian O. Thyroid hormone regulates adhesion, migration and matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity via alphavbeta3 integrin in myeloma cells. Oncotarget. 2014;5(15):6312–22.

Collie ES, Muscat GE. The human skeletal alpha-actin promoter is regulated by thyroid hormone: identification of a thyroid hormone response element. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3(1):31–42.

Conlin A, Smith G, Carey FA, Wolf CR, Steele RJ. The prognostic significance of K-ras, p53, and APC mutations in colorectal carcinoma. Gut. 2005;54(9):1283–6.

Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, Bets D, Mueser M, Harstrick A, Verslype C, Chau I, Van Cutsem E. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):337–45.

Davis PJ, Davis FB, Lin HY, Mousa SA, Zhou M, Luidens MK. Translational implications of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone initiated at its integrin receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(6):E1238-1246.

Davis PJ, Davis FB, Mousa SA. Thyroid hormone-induced angiogenesis. Curr Cardiol Reviews. 2009;5(1):12–6.

Davis PJ, Glinsky GV, Lin HY, Leith JT, Hercbergs A, Tang HY, Ashur-Fabian O, Incerpi S, Mousa SA. Cancer cell gene expression modulated from plasma membrane integrin alphavbeta3 by thyroid hormone and nanoparticulate tetrac. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:240.

Davis PJ, Goglia F, Leonard JL. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(2):111–21.

Davis PJ, Lin HY, Sudha T, Yalcin M, Tang HY, Hercbergs A, Leith JT, Luidens MK, Ashur-Fabian O, Incerpi S, Mousa SA. Nanotetrac targets integrin alphavbeta3 on tumor cells to disorder cell defense pathways and block angiogenesis. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1619–24.

Davis PJ, Mousa SA, Lin HY. Nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone: the integrin component. Physiol Rev, 2020.

Davis PJ, Mousa SA, Lin HY. Tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac), integrin alphavbeta3 and disabling of immune checkpoint defense. Future Med Chem. 2018;10(14):1637–9.

Davis PJ, Mousa SA, Schechter GP, Lin HY. Platelet ATP, thyroid hormone receptor on integrin alphavbeta3 and cancer metastasis. Horm Cancer. 2020;11(1):13–6.

Davis PJ, Shih A, Lin HY, Martino LJ, Davis FB. Thyroxine promotes association of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear thyroid hormone receptor (TR) and causes serine phosphorylation of TR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(48):38032–9.

Davis PJ, Sudha T, Lin HY, Mousa SA. Thyroid hormone, hormone analogs, and angiogenesis. Compr Physiol. 2015;6(1):353–62.

De Franceschi N, Hamidi H, Alanko J, Sahgal P, Ivaska J. Integrin traffic—the update. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(5):839–52.

Debruyne P, Vermeulen S, Mareel M. The role of the E-cadherin/catenin complex in gastrointestinal cancer. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1999;62(4):393–402.

Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, Rivera F, Kocakova I, Ruff P, Blasinska-Morawiec M, Smakal M, Canon JL, Rother M, Oliner KS, Wolf M, Gansert J. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4697–705.

Dragowska WH, Weppler SA, Qadir MA, Wong LY, Franssen Y, Baker JH, Kapanen AI, Kierkels GJ, Masin D, Minchinton AI, Gelmon KA, Bally MB. The combination of gefitinib and RAD001 inhibits growth of HER2 overexpressing breast cancer cells and tumors irrespective of trastuzumab sensitivity. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:420.

Fanjul-Fernandez M, Quesada V, Cabanillas R, Cadinanos J, Fontanil T, Obaya A, Ramsay AJ, Llorente JL, Astudillo A, Cal S, Lopez-Otin C. Cell-cell adhesion genes CTNNA2 and CTNNA3 are tumour suppressors frequently mutated in laryngeal carcinomas. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2531.

Favoni RE, Pattarozzi A, Lo CM, Barbieri F, Gatti M, Paleari L, Bajetto A, Porcile C, Gaudino G, Mutti L, Corte G, Florio T. Gefitinib targets EGFR dimerization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation to inhibit pleural mesothelioma cell proliferation. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10(2):176–91.

Flamini MI, Uzair ID, Pennacchio GE, Neira FJ, Mondaca JM, Cuello-Carrion FD, Jahn GA, Simoncini T, Sanchez AM. Thyroid hormone controls breast cancer cell movement via integrin alphaV/beta3/SRC/FAK/PI3-Kinases. Horm Cancer. 2017;8(1):16–27.

Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F, Orditura M, Castellano P, Troiani T, Imperatore V, Ciardiello F. Cetuximab, a chimeric human mouse anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of human colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(25):3654–60.

Galvez BG, Matias-Roman S, Yanez-Mo M, Vicente-Manzanares M, Sanchez-Madrid F, Arroyo AG. Caveolae are a novel pathway for membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase traffic in human endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(2):678–87.

Giaccone G, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, van Oosterom AT, Alfonso R, Smit EF, Martens M, Peters GJ, van der Vijgh WJ, Smith R, Averbuch S, Fandi A. Combination therapy with gefitinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(5):831–8.

Gionfra F, De Vito P, Pallottini V, Lin HY, Davis PJ, Pedersen JZ, Incerpi S. The role of thyroid hormones in hepatocyte proliferation and liver cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:532.

Glinskii AB, Glinsky GV, Lin HY, Tang HY, Sun M, Davis FB, Luidens MK, Mousa SA, Hercbergs AH, Davis PJ. Modification of survival pathway gene expression in human breast cancer cells by tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac). Cell Cycle. 2009;8(21):3562–70.

Goede V, Coutelle O, Neuneier J, Reinacher-Schick A, Schnell R, Koslowsky TC, Weihrauch MR, Cremer B, Kashkar H, Odenthal M, Augustin HG, Schmiegel W, Hallek M, Hacker UT. Identification of serum angiopoietin-2 as a biomarker for clinical outcome of colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab-containing therapy. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(9):1407–14.

Guernsey DL, Leuthauser SW. Correlation of thyroid hormone dose-dependent regulation of K-ras protooncogene expression with oncogene activation by 3-methylcholanthrene: loss of thyroidal regulation in the transformed mouse cell. Cancer Res. 1987;47(12):3052–6.

Herbst RS. Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(2 Suppl):21–6.

Ho Y, Sh Yang YC, Chin YT, Chou SY, Chen YR, Shih YJ, Whang-Peng J, Changou CA, Liu HL, Lin SJ, Tang HY, Lin HY, Davis PJ. Resveratrol inhibits human leiomyoma cell proliferation via crosstalk between integrin alphavbeta3 and IGF-1R. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;120:346–55.

Hsieh MT, Wang LM, Changou CA, Chin YT, Yang YSH, Lai HY, Lee SY, Yang YN, Whang-Peng J, Liu LF, Lin HY, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Crosstalk between integrin alphavbeta3 and ERalpha contributes to thyroid hormone-induced proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):24237–49.

Hu T, Li C. Convergence between Wnt-beta-catenin and EGFR signaling in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:236.

Huang TY, Chang TC, Chin YT, Pan YS, Chang WJ, Liu FC, Hastuti ED, Chiu SJ, Wang SH, Changou CA, Li ZL, Chen YR, Chu HR, Shih YJ, Cheng RH, Wu A, Lin HY, Wang K, Whang-Peng J, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. NDAT targets PI3K-mediated PD-L1 upregulation to reduce proliferation in gefitinib-resistant colorectal cancer. Cells. 1830;9(8):2020.

Jang M, Koh I, Lee JE, Lim JY, Cheong JH, Kim P. Increased extracellular matrix density disrupts E-cadherin/beta-catenin complex in gastric cancer cells. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(10):2704–13.

Janmaat ML, Giaccone G. Small-molecule epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncologist. 2003;8(6):576–86.

Janmaat ML, Rodriguez JA, Gallegos-Ruiz M, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Enhanced cytotoxicity induced by gefitinib and specific inhibitors of the Ras or phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase pathways in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(1):209–14.

Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Au HJ, Berry SR, Krahn M, Price T, Simes RJ, Tebbutt NC, van Hazel G, Wierzbicki R, Langer C, Moore MJ. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2040–8.

Khan K, Valeri N, Dearman C, Rao S, Watkins D, Starling N, Chau I, Cunningham D. Targeting EGFR pathway in metastatic colorectal cancer- tumour heterogeniety and convergent evolution. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;143:153–63.

King TD, Suto MJ, Li Y. The Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway: a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of triple negative breast cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(1):13–8.

Koizumi F, Kanzawa F, Ueda Y, Koh Y, Tsukiyama S, Taguchi F, Tamura T, Saijo N, Nishio K. Synergistic interaction between the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (“Iressa”) and the DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor CPT-11 (irinotecan) in human colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(3):464–72.

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, Grothey A, Vauthey JN, Nagorney DM, McWilliams RR. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677–83.

Kopetz S, Hoff PM, Morris JS, Wolff RA, Eng C, Glover KY, Adinin R, Overman MJ, Valero V, Wen S, Lieu C, Yan S, Tran HT, Ellis LM, Abbruzzese JL, Heymach JV. Phase II trial of infusional fluorouracil, irinotecan, and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer: efficacy and circulating angiogenic biomarkers associated with therapeutic resistance. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):453–9.

Kortum RL, Fernandez MR, Costanzo-Garvey DL, Johnson HJ, Fisher KW, Volle DJ, Lewis RE. Caveolin-1 is required for kinase suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1)-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation, H-RasV12-induced senescence, and transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(18):3461–72.

Kuramochi H, Nakajima G, Kaneko Y, Nakamura A, Inoue Y, Yamamoto M, Hayashi K. Amphiregulin and Epiregulin mRNA expression in primary colorectal cancer and corresponding liver metastases. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:88.

Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, Biedrzycki B, Donehower RC, Zaheer A, Fisher GA, Crocenzi TS, Lee JJ, Duffy SM, Goldberg RM, de la Chapelle A, Koshiji M, Bhaijee F, Huebner T, Hruban RH, Wood LD, Cuka N, Pardoll DM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Cornish TC, Taube JM, Anders RA, Eshleman JR, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA Jr. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–20.

Lee YS, Chin YT, Shih YJ, Nana AW, Chen YR, Wu HC, Yang YSH, Lin HY, Davis PJ. Thyroid hormone promotes beta-catenin activation and cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Horm Cancer. 2018;9(3):156–65.

Lee YS, Chin YT, Yang YSH, Wei PL, Wu HC, Shih A, Lu YT, Pedersen JZ, Incerpi S, Liu LF, Lin HY, Davis PJ. The combination of tetraiodothyroacetic acid and cetuximab inhibits cell proliferation in colorectal cancers with different K-ras status. Steroids. 2016;111:63–70.

Li J, Kleeff J, Giese N, Buchler MW, Korc M, Friess H. Gefitinib (‘Iressa’, ZD1839), a selective epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth, invasion, and colony formation. Int J Oncol. 2004;25(1):203–10.

Lin H-Y. Abstract C96: thyroid hormone induced Beta-catenin-dependent proliferation in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cancer Therapeutics. 2016;14:C96.

Lin HY, Chin YT, Nana AW, Shih YJ, Lai HY, Tang HY, Leinung M, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Actions of l-thyroxine and Nano-diamino-tetrac (Nanotetrac) on PD-L1 in cancer cells. Steroids. 2016;114:59–67.

Lin HY, Chin YT, Shih YJ, Chen YR, Leinung M, Keating KA, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. In tumor cells, thyroid hormone analogues non-immunologically regulate PD-L1 and PD-1 accumulation that is anti-apoptotic. Oncotarget. 2018;9(75):34033–7.

Lin HY, Chin YT, Yang YC, Lai HY, Wang-Peng J, Liu LF, Tang HY, Davis PJ. Thyroid hormone, cancer, and apoptosis. Compr Physiol. 2016;6(3):1221–37.

Lin HY, Cody V, Davis FB, Hercbergs AA, Luidens MK, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Identification and functions of the plasma membrane receptor for thyroid hormone analogues. Discov Med. 2011;11(59):337–47.

Lin HY, Glinsky GV, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Thyroid hormone and anti-apoptosis in tumor cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(17):14735–43.

Lin HY, Hopkins R, Cao HJ, Tang HY, Alexander C, Davis FB, Davis PJ. Acetylation of nuclear hormone receptor superfamily members: thyroid hormone causes acetylation of its own receptor by a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. Steroids. 2005;70(5–7):444–9.

Lin HY, Landersdorfer CB, London D, Meng R, Lim CU, Lin C, Lin S, Tang HY, Brown D, Van Scoy B, Kulawy R, Queimado L, Drusano GL, Louie A, Davis FB, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Pharmacodynamic modeling of anti-cancer activity of tetraiodothyroacetic acid in a perfused cell culture system. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7(2):e1001073.

Lin HY, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Demonstration of the receptor site for thyroid hormone on integrin alphavbeta3. Methods Mol Biol. 1801;61–65:2018.

Lin HY, Su YF, Hsieh MT, Lin S, Meng R, London D, Lin C, Tang HY, Hwang J, Davis FB, Mousa SA, Davis PJ. Nuclear monomeric integrin alphav in cancer cells is a coactivator regulated by thyroid hormone. FASEB J. 2013;27(8):3209–16.

Lin HY, Sun M, Tang HY, Lin C, Luidens MK, Mousa SA, Incerpi S, Drusano GL, Davis FB, Davis PJ. L-Thyroxine vs. 3,5,3’-triiodo-L-thyronine and cell proliferation: activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296(5):C980-991.

Lin SJ, Chin YT, Ho Y, Chou SY, Sh Yang YC, Nana AW, Su KW, Lim YT, Wang K, Lee SY, Shih YJ, Chen YR, Whang-Peng J, Davis PJ, Lin HY, Fu E. Nano-diamino-tetrac (NDAT) inhibits PD-L1 expression which is essential for proliferation in oral cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;120:1–11.

Liu L, Yang Y, Liu S, Tao T, Cai J, Wu J, Guan H, Zhu X, He Z, Li J, Song E, Zeng M, Li M. EGF-induced nuclear localization of SHCBP1 activates beta-catenin signaling and promotes cancer progression. Oncogene. 2019;38(5):747–64.

Liu YC, Yeh CT, Lin KH. Molecular functions of thyroid hormone signaling in regulation of cancer progression and anti-apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci 20(20), 2019.

Liu YY, Brent GA. Posttranslational modification of thyroid hormone nuclear receptor by phosphorylation. Methods Mol Biol. 1801;39–46:2018.

Lovly CM, Shaw AT. Molecular pathways: resistance to kinase inhibitors and implications for therapeutic strategies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(9):2249–56.

Luo J, Yao JF, Deng XF, Zheng XD, Jia M, Wang YQ, Huang Y, Zhu JH. 14, 15-EET induces breast cancer cell EMT and cisplatin resistance by up-regulating integrin alphavbeta3 and activating FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):23.

Martinelli E, De Palma R, Orditura M, De Vita F, Ciardiello F. Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;158(1):1–9.

Martinelli E, Troiani T, Morgillo F, Orditura M, De Vita F, Belli G, Ciardiello F. Emerging VEGF-receptor inhibitors for colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2013;18(1):25–37.

Matsuo M, Sakurai H, Ueno Y, Ohtani O, Saiki I. Activation of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways by fibronectin requires integrin alphav-mediated ADAM activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: a novel functional target for gefitinib. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(2):155–62.

Mayer A, Takimoto M, Fritz E, Schellander G, Kofler K, Ludwig H. The prognostic significance of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, epidermal growth factor receptor, and mdr gene expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1993;71(8):2454–60.

Meissner JD, Freund R, Krone D, Umeda PK, Chang KC, Gros G, Scheibe RJ. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-mediated phosphorylation of p300 enhances myosin heavy chain I/beta gene expression via acetylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells c1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(14):5907–25.

Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. The EGF receptor family as targets for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19(56):6550–65.

Meng R, Tang HY, Westfall J, London D, Cao JH, Mousa SA, Luidens M, Hercbergs A, Davis FB, Davis PJ, Lin HY. Crosstalk between integrin alphavbeta3 and estrogen receptor-alpha is involved in thyroid hormone-induced proliferation in human lung carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27547.

Messa C, Russo F, Caruso MG, Di Leo A. EGF, TGF-alpha, and EGF-R in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Acta Oncol. 1998;37(3):285–9.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–57.

Mori S, Wu CY, Yamaji S, Saegusa J, Shi B, Ma Z, Kuwabara Y, Lam KS, Isseroff RR, Takada YK, Takada Y. Direct binding of integrin alphavbeta3 to FGF1 plays a role in FGF1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18066–75.

Mousa SA, Glinsky GV, Lin HY, Ashur-Fabian O, Hercbergs A, Keating KA, Davis PJ. Contributions of Thyroid hormone to cancer metastasis. Biomedicines 6(3), 2018.

Nana AW, Chin YT, Lin CY, Ho Y, Bennett JA, Shih YJ, Chen YR, Changou CA, Pedersen JZ, Incerpi S, Liu LF, Whang-Peng J, Fu E, Li WS, Mousa SA, Lin HY, Davis PJ. Tetrac downregulates beta-catenin and HMGA2 to promote the effect of resveratrol in colon cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(3):279–93.

Nana AW, Wu SY, Yang YS, Chin YT, Cheng TM, Ho Y, Li WS, Liao YM, Chen YR, Shih YJ, Liu YR, Pedersen J, Incerpi S, Hercbergs A, Liu LF, Whang-Peng J, Davis PJ, Lin HY. Nano-diamino-tetrac (NDAT) enhances resveratrol-induced antiproliferation by action on the RRM2 pathway in colorectal cancers. Horm Cancer. 2018;9(5):349–60.

Normanno N, De Luca A, Maiello MR, Campiglio M, Napolitano M, Mancino M, Carotenuto A, Viglietto G, Menard S. The MEK/MAPK pathway is involved in the resistance of breast cancer cells to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207(2):420–7.

Normanno N, Tejpar S, Morgillo F, De Luca A, Van Cutsem E, Ciardiello F. Implications for KRAS status and EGFR-targeted therapies in metastatic CRC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(9):519–27.

Ono M, Kuwano M. Molecular mechanisms of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation and response to gefitinib and other EGFR-targeting drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(24):7242–51.

Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, Desai J, Hill A, Axelson M, Moss RA, Goldberg MV, Cao ZA, Ledeine JM, Maglinte GA, Kopetz S, Andre T. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1182–91.

Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, Miller VA, Pan Q, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF, Heelan RT, Kris MG, Varmus HE. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2(1):e17.

Park JJ, Yi JY, Jin YB, Lee YJ, Lee JS, Lee YS, Ko YG, Lee M. Sialylation of epidermal growth factor receptor regulates receptor activity and chemosensitivity to gefitinib in colon cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(7):849–57.

Park NJ, Wang XQ, Diaz A, Goos-Root DM, Bock C, Vaught JD, Sun WM, Strom CM. Measurement of cetuximab and panitumumab-unbound serum EGFR extracellular domain using an assay based on slow off-rate modified aptamer (SOMAmer) reagents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):71703.

Peng X, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Wang L, Song W, Li Q, Zhao R. Overexpressing modified human TRbeta1 suppresses the proliferation of breast cancer MDA-MB-468 cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(1):785–92.

Saeki T, Salomon DS, Johnson GR, Gullick WJ, Mandai K, Yamagami K, Moriwaki S, Tanada M, Takashima S, Tahara E. Association of epidermal growth factor-related peptides and type I receptor tyrosine kinase receptors with prognosis of human colorectal carcinomas. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1995;25(6):240–9.

Sandler B, Webb P, Apriletti JW, Huber BR, Togashi M, Cunha Lima ST, Juric S, Nilsson S, Wagner R, Fletterick RJ, Baxter JD. Thyroxine-thyroid hormone receptor interactions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(53):55801–8.

Schirripa M, Nappo F, Cremolini C, Salvatore L, Rossini D, Bensi M, Businello G, Pietrantonio F, Randon G, Fuca G, Boccaccino A, Bergamo F, Lonardi S, Dei Tos AP, Fassan M, Loupakis F. KRAS G12C metastatic colorectal cancer: specific features of a new emerging target population. Clin Colorectal Cancer, 2020.

Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, Nordlinger B, van de Velde CJ, Balmana J, Regula J, Nagtegaal ID, Beets-Tan RG, Arnold D, Ciardiello F, Hoff P, Kerr D, Kohne CH, Labianca R, Price T, Scheithauer W, Sobrero A, Tabernero J, Aderka D, Barroso S, Bodoky G, Douillard JY, El Ghazaly H, Gallardo J, Garin A, Glynne-Jones R, Jordan K, Meshcheryakov A, Papamichail D, Pfeiffer P, Souglakos I, Turhal S, Cervantes A. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer: a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(10):2479–516.

Sforza V, Martinelli E, Ciardiello F, Gambardella V, Napolitano S, Martini G, Della CC, Cardone C, Ferrara ML, Reginelli A, Liguori G, Belli G, Troiani T. Mechanisms of resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(28):6345–61.

Shih YW, Chien ST, Chen PS, Lee JH, Wu SH, Yin LT. Alpha-mangostin suppresses phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced MMP-2/MMP-9 expressions via alphavbeta3 integrin/FAK/ERK and NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2010;58(1):31–44.

Shinderman-Maman E, Cohen K, Weingarten C, Nabriski D, Twito O, Baraf L, Hercbergs A, Davis PJ, Werner H, Ellis M, Ashur-Fabian O. The thyroid hormone-alphavbeta3 integrin axis in ovarian cancer: regulation of gene transcription and MAPK-dependent proliferation. Oncogene. 2016;35(15):1977–87.

Shitoh K, Koinuma K, Furukawa T, Okada M, Nagai H. Mutation of beta-catenin does not coexist with K-ras mutation in colorectal tumorigenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(10):1631–3.

Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze’ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(10):5522–7.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34.

Song J, Zhu J, Zhao Q, Tian B. Gefitinib causes growth arrest and inhibition of metastasis in human chondrosarcoma cells. J BUON. 2015;20(3):894–901.

Spano JP, Fagard R, Soria JC, Rixe O, Khayat D, Milano G. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in colorectal cancer: preclinical data and therapeutic perspectives. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(2):189–94.

Tebbutt N, Pedersen MW, Johns TG. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(9):663–73.

Toda D, Ota T, Tsukuda K, Watanabe K, Fujiyama T, Murakami M, Naito M, Shimizu N. Gefitinib decreases the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinase and the adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins of colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(1A):129–34.

Troiani T, Napolitano S, Della Corte CM, Martini G, Martinelli E, Morgillo F, Ciardiello F. Therapeutic value of EGFR inhibition in CRC and NSCLC: 15 years of clinical evidence. ESMO Open. 2016;1(5):e000088.

Troiani T, Napolitano S, Vitagliano D, Morgillo F, Capasso A, Sforza V, Nappi A, Ciardiello D, Ciardiello F, Martinelli E. Primary and acquired resistance of colorectal cancer cells to anti-EGFR antibodies converge on MEK/ERK pathway activation and can be overcome by combined MEK/EGFR inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(14):3775–86.

Vermeulen SJ, Nollet F, Teugels E, Vennekens KM, Malfait F, Philippe J, Speleman F, Bracke ME, van Roy FM, Mareel MM. The alphaE-catenin gene (CTNNA1) acts as an invasion-suppressor gene in human colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999;18(4):905–15.

Wang W, Kandimalla R, Huang H, Zhu L, Li Y, Gao F, Goel A, Wang X. Molecular subtyping of colorectal cancer: recent progress, new challenges and emerging opportunities. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;55:37–52.

Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94(5):625–34.

Wee P, Wang Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel) 9(5), 2017.

White BD, Chien AJ, Dawson DW. Dysregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):219–32.

Whitmarsh AJ. Regulation of gene transcription by mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773(8):1285–98.

Xie YH, Chen YX, Fang JY. Comprehensive review of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct Tar 5(1), 2020.

Yazdi MH, Faramarzi MA, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A comprehensive review of clinical trials on EGFR inhibitors such as cetuximab and panitumumab as monotherapy and in combination for treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2015;7(4):134–44.

Yu-Jing YJ, Zhang CM, Liu ZP. Recent developments of small molecule EGFR inhibitors based on the quinazoline core scaffolds. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12(4):391–406.

Yuan HH, Han Y, Bian WX, Liu L, Bai YX. The effect of monoclonal antibody cetuximab (C225) in combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (ZD1839) on colon cancer cell lines. Pathology. 2012;44(6):547–51.

Zhang X, Nagahara H, Mimori K, Inoue H, Sawada T, Ohira M, Hirakawa K, Mori M. Mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor in colon cancer indicate susceptibility or resistance to gefitinib. Oncol Rep. 2008;19(6):1541–4.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Ms. Gloria and Ms. Evelyn for their stunning proofreading expertise. The authors would like to extend their most sincere appreciation to Miss ABu for her prodigious research contributions from our group as mentioned in this review article. Miss Ya-Jung Shih’s extraordinary drawing skill is sincerely appreciated too.

Funding

The research described in this article from our team was supported in part by an intra-institutional grant from E-Da Medical Center (EDAHP 109011 to Dr. Po-Jui Ko), by the Chair Professor Research Fund to Dr. K. Wang and Dr. J. Whang-Peng, by TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan, by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST109-2124-M-038-001, MOST109-2314-B-038-125 and MOST109-2314-B-038-038), and by a gift from Dr. Paul J. Davis to Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. This funding source had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its study, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YCY, PJK, HYL, and YSP wrote the manuscript. YCY, PJK YSP, KW, JWP, PJD, and HYL contributed with intellectual expertise and/or discussed the results. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors declare that this article is original, has never been published, and has not been submitted to any other journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, YC.S.H., Ko, PJ., Pan, YS. et al. Role of thyroid hormone-integrin αvβ3-signal and therapeutic strategies in colorectal cancers. J Biomed Sci 28, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-021-00719-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-021-00719-5