Abstract

Background

Gut and oral microbes form complex communities and play key roles in co-evolution with their hosts. However, little is understood about the bacterial community in lizards.

Results

In this study, we investigated the gut and oral bacterial communities in Japalura sensu lato from Sichuan Province, China, using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Results showed that Bacteroidota (36.5%) and Firmicutes (32.8%) were the main phyla in the gut, while Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteriota were the dominant phyla in the oral cavity. 16 S rRNA sequencing analysis of fecal samples showed that: (1) Bacteroidota was the most abundant in Japalura sensu lato, which was different from the bacterial community of insectivorous animals; (2) Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, Fusobacteriota, and Cyanobacteria were the most abundant phylum in Japalura sensu lato. (3) Proteobacteria was the dominant phylum in Japalura sensu lato and other domestic insectivorous lizards (Shinisaurus crocodilurus, Phrynocephalus vlangalii, and Takydromus septentrionalis); (4) Comparing with the bacterial community of Shinisaurus crocodilurus, Phrynocephalus vlangalii, Takydromus septentrionalis, Liolaemus parvus, L. ruibali, and Phymaturus williamsi, Desulfobacterota was uniquely present in the gut of Japalura sensu lato. 16 S rRNA sequencing of oral samples showed that Chloroflexi and Deinococcota phyla were enriched in the oral cavity, which may have a significant influence on living in extreme environments.

Conclusions

Thus, based on 16 S rRNA sequencing analysis of the community composition of the gut and oral microbiomes, this study firstly represents a foundation for understanding the gut and oral microbial ecology of Japalura sensu lato, and constitutes a detail account of the diversity of the microbiota inhabiting the gut and oral cavity of Japalura sensu lato. Further researches will continue to reveal how gut and oral microbial communities may be impacting the ecology and evolution of lizards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Reptiles are an ancient group containing more than 10 000 species. Over 60% of reptiles belong to the clade Sauria, also known as lizards [1], and exhibit marked diversity in body size, shape, behavior, and life-history strategies [2, 3]. The varied ecological, physiological, and behavioral characteristics of lizards can influence the ecology of their gut and oral microbial communities [4]. However, few investigations have been conducted on the microbial communities of reptiles [5]. The Chinese tree dragon (Japalura sensu lato) is primarily distributed in the Yangtze River Basin in southwestern China, including the Yunnan, Sichuan, Chongqing, and Hubei provinces [6]. These lizards often appear on the edge of forests among shrubs and gravel. They are good at climbing, strongly arboreal, highly active, exclusively insectivorous, and usually kept as pets [7].

Vertebrates and invertebrates maintain a complex relationship with their gastrointestinal and oral microbial communities [8, 9]. Gut microbes can affect host behavior [10, 11], immunity [12], nutrition [13] and reproductive isolation [14], ecology, and evolution. To date, the gut microbial communities of nine species of lizards have been reported, including Liolaemus parvus, Liolaemus ruibali, Phymaturus williamsi [15], Anolis sagrei [16], Takydromus septentrionalis [17], Crocodile Lizards [18], land and marine iguanas [19], Phrynocephalus vlangalii [20], Diploderma vela [21]. However, two important issues still need to be elucidated: (1) ecology of gut bacterial diversity and (2) how diet, altitude, physiology, and genetics determine microbial population structure [22,23,24].

Normal oral flora is comprised of various microorganisms, which can be protective and provide an essential barrier through interactions with the host immune system [25]. In addition, oral cavity microbes have co-evolved with their hosts and adapted to diverse conditions for colonization resistance [26]. However, little is understood about the oral bacterial community in lizards.

To expand our understanding of gut and oral microbial diversity in Japalura sensu lato, we firstly explored the composition of bacterial communities in the gut and oral cavity using 16 S rRNA sequencing analysis.

Methods

Description of samples

The Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research program included a focus on gut and oral cavity bacterial diversity in reptiles. As such, in the July of 2020 (average temperature 28℃, average humidity 63%), Ten of Japalura sensu lato lizards (six females, four males) were 30–33 cm in length and collected from Quebrada in the Laojun Mountains of Sichuan, China, about 110 km from Yibin city (28°84’71’’N; 104°25’30’’E, ~ 600 m above sea level). The lizards, according to the captured time, were named 1–10, respectively and then individually placed in sterilized tubs overnight for the collection of fecal and oral samples using sterile swabs. Each lizard was collected the fecal (named F1-10) and oral (named S1-10) samples respectively. The sterile swabs were placed in RNase-free tubes and transported on dry ice to LE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). To prevent contamination, the samples were cleaned in advance and none of the sample donors received antibiotic or probiotic therapy. The lizards were released back into the wild after sample collection. We also collected three soil samples (named soil1, soil 2 and soil 3) and foliage from a number of plant species (3 samples, named plant 1, plant 2 and plant 3 for each species of Oxalis corniculate, Setaria viridis, Houttuynia cordata, Eremochloa ciliaris, Diplopterygium glaucum, and Alsophila spinulosa), which were collected opportunistically in areas where lizards were captured (< 10 m from point of capture) and pretreated with ethanol-sterilized scissors, placed in RNase-free tubes, and transported on dry ice to LE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

The procedures of DNA extraction and PCR amplification were described as previous [27, 28]. Briefly, Microbial DNA was extracted from the fecal and oral samples using the EZNA® Stool DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The V4-V5 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene was amplified by PCR using primers 515F 5’-barcode-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3’ and 926R 5’-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3’, where the barcode is an eight-base sequence unique to each sample [29, 30]. PCR was performed in triplicate in a 20-µL mixture containing 4 µL of 5 × FastPfu Buffer, 2 µL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.4 µL of FastPfu Polymerase, and 10 ng of template DNA. Amplicons were extracted from 2% agarose gels and purified using a AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Library Construction and sequencing

As previous described [31], the purified PCR products were quantified by Qubit®3.0 (Life Invitrogen) and every 24 amplicons with different barcodes were mixed equally. The pooled DNA product was used to construct an Illumina paired-end library following the Illumina genomic DNA library preparation procedure. The amplicon library was paired-end sequenced (2 × 250) on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Shanghai BIOZERON Co., Ltd., China) according to standard protocols.

Processing of sequencing data

Raw fastq files were first demultiplexed using in-house Perl scripts according to the barcode sequence information for each sample with the following criteria: (i) The 250-bp reads were truncated at any site receiving an average quality score < 20 over a 10-bp sliding window, with truncated reads shorter than 50 bp discarded; (ii) exact barcode matching, two nucleotide mismatches in primer matching, and reads containing ambiguous characters were removed; (iii) only sequences with an overlap longer than 10 bp were assembled according to their overlap sequence [31]. Reads that could not be assembled were discarded.

Statistical analysis

Alpha-diversity (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, coverage indices) was analyzed using Mothur (v1.35.1) [32] following the protocols of Schloss [33]. The Shannon index and the Chao1 index using normalized OTU table. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis distance metrics was performed in R v3.4.4 to explore the differences in community structures [34]. Comparison across groups were conducted using the adonis function in R on the distance matrices with 999 permutations [35]. Other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v13.0. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered with a 97% similarity cutoff using UPARSE v7.1 (http://drive5.com/uparse/) and chimeric sequences were identified and removed using UCHIME (v4.2.40). The phylogenetic affiliation of each 16 S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed using RDP Classifier (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) against the SILVA (SSU132)16 S rRNA database with a confidence threshold of 70% [36]. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was employed to explore the relationship between environmental factors and bacterial communities. Community composition was analyzed at the domain, phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels. For identification of biomarkers for highly dimensional colonic bacteria, LEfSe (linear discriminant analysis effect size) analysis was performed [37]. Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test was used to examine changes and dissimilarities among classes, followed by local-density approximation (LDA) analysis to determine the size effect of each distinctively abundant taxa [38]. Venn diagrams were drawn using the “Draw Venn Diagram” online tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn) to analyze overlapping and unique OTUs during the treatment processes.

Results

Description of the sequencing data

We obtained 1 532 476 raw reads from MiSeq analysis of 26 samples, ranging from 30 470 to 175 731 reads per sample. After read-quality filtering, a total of 1 242 144 quality-filtered reads were obtained, ranging from 29 761 to 59 009 reads per sample, with an average length of 403.58–423.71 bp. A total of 6 156 OTUs were extracted, ranging from 28 982 to 55 646 reads per sample. To compare diversity indices, alpha-diversity (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, coverage indices), which considers both richness and diversity, was analyzed. The mean coverages of the fecal, oral, and environment groups were 0.997447, 0.9975551, and 0.992444833, respectively (Table 1), indicating that sequencing depth was sufficient to capture the true state of the microorganisms in the samples. The Chao1 estimators were significantly different between the fecal and environment groups (P < 0.01) and between the oral and environment groups (P < 0.01) but were not statistically different between the fecal and oral groups (Table 1), indicating that OTU richness in the fecal and oral groups was lower than that in the environment groups. The Shannon and Simpson indices were shown that oral groups had a lower community diversity than the fecal and environment groups (Table 1). Rarefaction curves are commonly used to describe the diversity in samples within a group. Here, all curves asymptotically approached a plateau, suggesting that they accurately reflected the microbial community and that the results were sufficient to estimate microbial diversity (Fig. 1A).

A Rarefaction curves of 10 fecal samples (F1–F10), 10 oral samples (S1–S10), three soil samples (soil1–soil3), and three plant samples (plant1–plant3). To evaluate sampling depth, rarefaction curves of microbial communities based on 16 S rRNA gene sequences are shown. B Venn diagram of OTUs in feces group, oral cavity group, and environment group

Based on Venn diagram analysis, 353 OTUs were shared among the fecal, oral, and environment groups. In addition, 976, 750, and 2 582 OTUs were exclusive to the fecal, oral, and environment groups, respectively (Fig. 1B).

We performed PCoA of overall diversity based on Bray-Curtis distance metrics to compare the microbial diversity of all groups. Analysis showed that there was a significant effect of Japalura sensu lato on fecal, oral and environment samples (adonis: feces and oral cavity group, R2 = 0.17, P < 0.01; feces and environment group, R2 = 0.20, P < 0.01; oral cavity and environment group, R2 = 0.19, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and clustering analysis, representing dissimilarity in bacterial structure among fecal, oral, and environment (soil and plant) samples. Distances between samples based on OTU composition similarity (OTU similarity ≥ 97%) calculated using unweighted UniFrac distances were visualized by PCoA plots. Percentage of variation explained by PC1 and PC2 are noted on axes

Gut microbial diversity and community composition

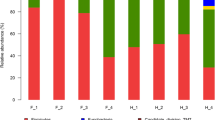

The 10 most abundant phyla, families, and genera in the fecal samples are shown in Fig. 3 and Table S1. Bacteroidota (36.5%) was the most dominant phylum in the fecal samples, followed by Firmicutes (32.8%), Proteobacteria (19.1%), Actinobacteriota (3.8%), Fusobacteriota (1.8%), Verrucomicrobiota (1.3%), and Desulfobacterota (1.0%), with Deinococcota (0.9%), Acidobacteriota (0.8%), and Cyanobacteria (0.6%) showing relative abundances of < 1.0%.

At the family level, Lachnospiraceae (17.0%) and Bacteroidaceae (15.8%) were the most dominant in the gut, followed by Chitinophagaceae (8.0%), Tannerellaceae (5.3%), Rhizobiaceae (4.3%), Marinifilaceae (4.1%), Clostridiaceae (3.9%), and Rhodanobacteraceae (3.2%).

At the genus level, Bacteroides (15.8%) was the most dominant, followed by Vibrionimonas (7.05), 28 − 4 (5.7%), Parabacteroides (4.4%), Clostridium sensu stricto 1 (3.9%), Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group (3.6%), and Rhodanobacter (3.1%) (Fig. 3).

For the community composition of fecal and environment samples, seven kinds of bacteria, including Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Acidobacteriota, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobiota, were shared in the top 10 dominant phyla.

Oral cavity microbial diversity and community composition

Bacterial composition in the oral cavity at the phylum level is shown in Fig. 3 and Table S1. Results showed that Proteobacteria (47.0%) was the dominant phylum, followed by Bacteroidota (18.9%), Firmicutes (15.4%), Actinobacteriota (6.9%), and Deinococcota (6.1%), with Myxococcota (0.9%), Acidobacteriota (0.8%), Gemmatimonadota (0.8%), Chloroflexi (0.8%), and unclassified (0.5%) showing relative abundances of < 1.0%.

At the family level, Chitinophagaceae (12.9%) was the most dominant, followed by Burkholderiaceae (10.0%), Rhizobiaceae (6.7%), Moraxellaceae (6.2%), Trueperaceae (6.1%), Bacillaceae (5.2%), Rhodanobacteraceae (4.9%), Staphylococcaceae (3.8%), Xanthobacteraceae (3.3%), and Caulobacteraceae (3.0%).

At the genus level, Vibrionimonas (11.2%) was the most dominant, followed by Ralstonia (9.9%), Truepera (6.1%), Enhydrobacter (4.9%), Rhodanobacter (4.3%), Bacillus (4.1%), Mesorhizobium (3.9%), and Staphylococcus (3.8%) (Fig. 3).

For the community composition of fecal and oral samples, six types of bacteria, including Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Deinococcota and Acidobacteriota, were shared in the top 10 dominant phyla.

Comparison of differentially enriched taxa among groups

Using LEfSe analysis, we selected species showing differences among groups. The results included a LDA distribution histogram, an evolutionary branch diagram (phylogenetic distribution), and an abundance comparison diagram of biomarkers showing statistical differences (LDA score > 2) between groups (Fig. 4). In total, 37 and 18 types of bacteria were enriched in the gut and oral cavity, respectively. Pseudomonadales (Gammaproteobacteria), Acidobacteriota, and Limnobacter were enriched in the fecal group and played key roles in the microbial community. Burkholderiales, Burkholderiaceae, Staphylococcaceae, Staphylococcales, Bacillales, Bacillaceae, Bacillus, Janibacter and Intrasporangiaceae were enriched in the oral cavity.

LEfSe (linear discriminant analysis effect size) analysis of microbiota composition of fecal, oral, and environment samples (LDA > 2). a Histogram of LDA scores for differentially abundant features in feces group, oral cavity group, and environment group. LEfSe scores were interpreted as degree of consistent difference in relative abundance of microbial communities in fecal, oral, and environment (soil and plant) samples. b Taxonomic representation of statistical and biological differences between feces group, oral cavity group and environment group. Differences are represented by colored circles. Color represents classification level and size is proportional to taxon abundance, representing phylum, class, order, and family

Discussion

According to the diversity and abundance of gut and oral microbiota, many factors, including host species, sex, region, and season, are related to the ecology and behavior of the hosts [15]. A few studies have been performed to examine the differences in gut microbial compositions and abundances in lizards, which suggested that lizards and their microbiota coevolve together [18, 39, 40]. Japalura sensu lato is unique to China, whether the gut and oral microbiota is associated with the host habitats and ecology was needed to be determined.

In the present study, Bacteroidetes (36.5%) and Firmicutes (32.8%) were the dominant phyla found in fecal samples, accounting for 69.3% of sequences, similar to the gut community composition reported in lizard species [19, 20]. Nonetheless, insectivores (Japalura sensu lato) (36.5%) and omnivores (L. parvus and L. ruibali) (35–39%) exhibited higher abundances of Bacteroidetes than herbivore (P. williamsi) (11–15%) [15]. Although Bacteroidetes are abundant in many mammalian gut communities, they show lower abundance in insectivorous mammals such as hedgehogs and house shrews (Suncus murinus) [41, 42]. The function of Bacteroidetes is to degrade ingested plant-derived material and ferment carbohydrates and short-chain fatty acids [5]. Further research is needed to investigate the role of Bacteroides in the insectivorous habit of Japalura sensu lato.

Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, Fusobacteriota, and Cyanobacteria were enriched in Japalura sensu lato, Shinisaurus crocodilurus, Phrynocephalus vlangalii, Takydromus septentrionalis, Liolaemus parvus, L. ruibali, and Phymaturus williamsi. Proteobacteria was commonly present in the domestic insectivorous lizards (i.e., Japalura sensu lato, Shinisaurus crocodilurus, Phrynocephalus vlangalii, and Takydromus septentrionalis), but absent from the omnivores (L. parvus and L. ruibali) and herbivores (P. williamsi) [15, 17, 18, 20]. Proteobacteria can enhance cellulose activity, degrade various aromatic compounds, and promote nutrient absorption in hosts [43]. We found that Desulfobacterota was the seventh most abundant phylum in the gut of Japalura sensu lato but was absent in the six other lizard species mentioned above. Furthermore, Desulfobacterota may be important for sulfate-reducing and fermentative [44, 45]. Based on the above results, we found that gut microbiota abundance and composition were affected by various factors, including geographical region, domestication, diet, and genotype of hosts.

Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes are the most common phyla found in oropharyngeal samples from various species (e.g., humans, murines, felines, canines, chimpanzees, and hawks) [46,47,48,49,50]. Very few studies have investigated the bacterial composition of the oral cavity in lizards, with research limited to the isolation of bacterial clones from oral and saliva samples using aerobic and anaerobic cultures [51,52,53] and reports of Staphylococcus aureus and Serratia marcescens infections in humans following lizard bites [54, 55]. In the current study, we investigated the oral bacterial community in Japalura sensu lato. Results showed that Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteriota were the dominant phyla in the oral cavity, suggesting similar oropharyngeal bacterial composition as the above hosts. Chloroflexi contains anaerobic chemoorganoheterotrophic bacteria with fermentative metabolism in digestive systems [56] and is a dominant phylum in anaerobic wastewater [57]. Thus, Chloroflexi was the ninth most abundant phylum in Japalura sensu lato, which may contribute to its anaerobic fermentation. The genus Truepera, which belongs to the phylum Deinococcota, can grow in alkaline, saline, and high temperature environments and is also present in cultivated olives [58, 59]. Our results showed that Truepera was a dominant phylum, family, and genus in the oral cavity of Japalura sensu lato, which may have high impact on the lizard’s ability to live in extreme environments and regulate the lizard’s body temperature, such as found in southern China with very hot and humid summers. There is another possibility that it is associated with diet, which can shape the microbial community [22].

This study had three main limitations. Firstly, we determined the sex of the lizards, but did not identify their age, which can affect bacterial community composition. Secondly, the samples were collected from one location (Laojun Mountains) and the sample size was small. Thirdly, we did not investigate the influence of season. Thus, our findings should be confirmed using a larger sample size and more collection locations.

Conclusions

We investigated the composition of the gut and oral bacterial community in an insectivorous lizard species (Japalura sensu lato). Our results indicated that Proteobacteria was commonly present in domestic insectivorous lizards. Desulfobacterota was uniquely present in the gut of Japalura sensu lato but was absent in the above six lizard species. Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteriota were the dominant phyla in the oral cavity. Furthermore, our study provides new insight into the complex bacterial community and ecology of Japalura sensu lato and offers a basic database for further investigations.

Availability of data and materials

All 16 S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession number PRJNA771761: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA771761.

Abbreviations

- L. parvus :

-

Liolaemus parvus

- L. ruibali :

-

Liolaemus ruibali

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

References

Uetz P, Hošek J. The Reptile Database. 2016.

Marki PZ, Jønsson KA, Irestedt M, Nguyen JM, Rahbek C, Fjeldså J. Supermatrix phylogeny and biogeography of the Australasian Meliphagides radiation (Aves: Passeriformes). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;107:516–29.

Woltering JM. From lizard to snake; behind the evolution of an extreme body plan. Curr Genomics. 2012;13(4):289–99.

Pianka ER, Vitt LJ. Lizards: windows to the evolution of diversity 2003.

Colston TJ, Jackson CR. Microbiome evolution along divergent branches of the vertebrate tree of life: what is known and unknown. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(16):3776–800.

Huang W, Luo H, Luo S, Huang A, Ni Q, Yao Y, Xu H, Zeng B, Li Y, Wei Z, et al. The complete mitogenome of the splendid japalure Japalura splendida (Squamata, Agamidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 2019;4(2):2641–2.

Wang Guang-li GZ-f, Yu Ping-jing, ZHao Er-mi. Behaviour of Japalura splendida under Artificial Feeding Condition. Sichuan J Zool. 2007;4:834–836.985.

McFall-Ngai M, Hadfield MG, Bosch TC, Carey HV, Domazet-Lošo T, Douglas AE, Dubilier N, Eberl G, Fukami T, Gilbert SF, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(9):3229–36.

Kuramitsu HK, He X, Lux R, Anderson MH, Shi W. Interspecies interactions within oral microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(4):653–70.

Archie EA, Theis KR. Animal behaviour meets microbial ecology. Animal Behav. 2011;82(3):425–36.

Ezenwa VO, Gerardo NM, Inouye DW, Medina M, Xavier JB. Microbiology. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science. 2012;338(6104):198–9.

Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291(5505):881–4.

Mackie RI. Mutualistic fermentative digestion in the gastrointestinal tract: diversity and evolution. Integrative Comparative Biol. 2002;42(2):319–26.

Shropshire JD, Bordenstein SR. Speciation by Symbiosis: the Microbiome and Behavior. mBio. 2016;7(2):e01785.

Kohl KD, Brun A, Magallanes M, Brinkerhoff J, Laspiur A, Acosta JC, Caviedes-Vidal E, Bordenstein SR. Gut microbial ecology of lizards: insights into diversity in the wild, effects of captivity, variation across gut regions and transmission. Mol Ecol. 2017;26(4):1175–89.

Ren T, Kahrl AF, Wu M, Cox RM. Does adaptive radiation of a host lineage promote ecological diversity of its bacterial communities? A test using gut microbiota of Anolis lizards. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(19):4793–804.

Zhou J, Zhao YT, Dai YY, Jiang YJ, Lin LH, Li H, Li P, Qu YF, Ji X. Captivity affects diversity, abundance, and functional pathways of gut microbiota in the northern grass lizard Takydromus septentrionalis. MicrobiologyOpen. 2020;9(9):e1095.

Jiang HY, Ma JE, Li J, Zhang XJ, Li LM, He N, Liu HY, Luo SY, Wu ZJ, Han RC, et al. Diets Alter the Gut Microbiome of Crocodile Lizards. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2073.

Hong PY, Wheeler E, Cann IK, Mackie RI. Phylogenetic analysis of the fecal microbial community in herbivorous land and marine iguanas of the Galápagos Islands using 16S rRNA-based pyrosequencing. ISME J. 2011;5(9):1461–70.

Zhang W, Li N, Tang X, Liu N, Zhao W. Changes in intestinal microbiota across an altitudinal gradient in the lizard Phrynocephalus vlangalii. Ecol Evol. 2018;8(9):4695–703.

Zhu W, Shi X, Qi Y, Wang X, Chang L, Zhao C, Zhu L, Jiang J. Commensal microbiota and host metabolic divergence are associated with the adaptation of Diploderma vela to spatially heterogeneous environments. Integrative Zool. 2022;17(3):346–65.

David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–63.

McKenney EA, Williamson L, Yoder AD, Rawls JF, Bilbo SD, Parker W. Alteration of the rat cecal microbiome during colonization with the helminth Hymenolepis diminuta. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(3):182–93.

Moeller AH, Li Y, Mpoudi Ngole E, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Lonsdorf EV, Pusey AE, Peeters M, Hahn BH, Ochman H. Rapid changes in the gut microbiome during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(46):16431–5.

Oh C, Lee K, Cheong Y, Lee SW, Park SY, Song CS, Choi IS, Lee JB. Comparison of the Oral Microbiomes of Canines and Their Owners Using Next-Generation Sequencing. PloS one. 2015;10(7):e0131468.

He X, McLean JS, Guo L, Lux R, Shi W. The social structure of microbial community involved in colonization resistance. ISME J. 2014;8(3):564–74.

Yuan J, Wang Z, Wang B, Mei H, Zhai X, Zhuang Z, Chen M. Non-Specific Immunity Associated Gut Microbiome in Aristichthys nobilis under Different Rearing Strategies. Genes (Basel). 2021;12(6):916. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060916.

Song X, Wang H. Investigation of microbial contamination in a chicken slaughterhouse environment. J Food Sci. 2021;86(8):3598–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15842.

Sun DL, Jiang X, Wu QL, Zhou NY. Intragenomic heterogeneity of 16S rRNA genes causes overestimation of prokaryotic diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(19):5962–9.

Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:38.

Wu ZF, Zou K, Wu GN, Jin ZJ, Xiang CJ, Xu S, Wang YH, Wu XY, Chen C, Xu Z et al. A comparison of tumor-associated and non-tumor-associated gastric microbiota in gastric cancer patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(5):1673–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06415-y.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537–41.

Schloss PD, Gevers D, Westcott SL. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PloS one. 2011;6(12):e27310.

Hu R, Yuan J, Meng Y, Wang Z, Gu Z: Pathogenic Elizabethkingia miricola Infection in Cultured Black-Spotted Frogs, China, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(12):2055–2059.

Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust J Ecol. 1993;18(1):117–43.

Amato KR, Yeoman CJ, Kent A, Righini N, Carbonero F, Estrada A, Gaskins HR, Stumpf RM, Yildirim S, Torralba M, et al. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. ISME J. 2013;7(7):1344–53.

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60.

Ijaz MU, Ahmed MI, Zou X, Hussain M, Zhang M, Zhao F, Xu X, Zhou G, Li C. Beef, Casein, and Soy Proteins Differentially Affect Lipid Metabolism, Triglycerides Accumulation and Gut Microbiota of High-Fat Diet-Fed C57BL/6J Mice. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2200.

Zhang W, Li N, Tang X, Liu N, Zhao W. Changes in intestinal microbiota across an altitudinal gradient in the lizard Phrynocephalus vlangalii. Ecol Evol. 2018;8(9):4695–703.

Zhou J, Zhao YT, Dai YY, Jiang YJ, Lin LH, Li H, Li P, Qu YF, Ji X. Captivity affects diversity, abundance, and functional pathways of gut microbiota in the northern grass lizard Takydromus septentrionalis. Microbiol Open. 2020;9(9):e1095.

Shinohara A, Nohara M, Kondo Y, Jogahara T, Nagura-Kato GA, Izawa M, Koshimoto C. Comparison of the gut microbiotas of laboratory and wild Asian house shrews (Suncus murinus) based on cloned 16S rRNA sequences. Experiment Anim. 2019;68(4):531–9.

Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS, Schlegel ML, Tucker TA, Schrenzel MD, Knight R, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science. 2008;320(5883):1647–51.

Reid NM, Addison SL, Macdonald LJ, Lloyd-Jones G: Biodiversity of active and inactive bacteria in the gut flora of wood-feeding huhu beetle larvae (Prionoplus reticularis). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(19):7000–7006.

Jackson BE, Bhupathiraju VK, Tanner RS, Woese CR, McInerney MJ. Syntrophus aciditrophicus sp. nov., a new anaerobic bacterium that degrades fatty acids and benzoate in syntrophic association with hydrogen-using microorganisms. Arch Microbiol. 1999;171(2):107–14.

Liu Y, Balkwill DL, Aldrich HC, Drake GR, Boone DR. Characterization of the anaerobic propionate-degrading syntrophs Smithella propionica gen. nov., sp. nov. and Syntrophobacter wolinii. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49(Pt):545–56.

Gong H, Shi Y, Zhou X, Wu C, Cao P, Xu C, Hou D, Wang Y, Zhou L. Microbiota in the Throat and Risk Factors for Laryngeal Carcinoma. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(23):7356–7363.

Chun J, Kim KY, Lee JH, Choi Y. The analysis of oral microbial communities of wild-type and toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice using a 454 GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencer. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:101.

Sturgeon A, Stull JW, Costa MC, Weese JS. Metagenomic analysis of the canine oral cavity as revealed by high-throughput pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. Vet Microbiol. 2013;162(2–4):891–8.

Dewhirst FE, Klein EA, Bennett ML, Croft JM, Harris SJ, Marshall-Jones ZV. The feline oral microbiome: a provisional 16S rRNA gene based taxonomy with full-length reference sequences. Vet Microbiol. 2015;175(2–4):294–303.

Adler CJ, Malik R, Browne GV, Norris JM. Diet may influence the oral microbiome composition in cats. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):23.

Goldstein EJ, Tyrrell KL, Citron DM, Cox CR, Recchio IM, Okimoto B, Bryja J, Fry BG. Anaerobic and aerobic bacteriology of the saliva and gingiva from 16 captive Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis): new implications for the “bacteria as venom” model. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 2013;44(2):262–72.

Montgomery JM, Gillespie D, Sastrawan P, Fredeking TM, Stewart GL. Aerobic salivary bacteria in wild and captive Komodo dragons. J Wildlife Dis. 2002;38(3):545–51.

Fry BG, Wroe S, Teeuwisse W, van Osch MJ, Moreno K, Ingle J, McHenry C, Ferrara T, Clausen P, Scheib H, et al. A central role for venom in predation by Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon) and the extinct giant Varanus (Megalania) priscus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(22):8969–74.

Hsieh S, Babl FE. Serratia marcescens cellulitis following an iguana bite. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28(5):1181–2.

Grim KD, Doherty C, Rosen T. Serratia marcescens bullous cellulitis after iguana bites. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):1075–6.

McIlroy SJ, Kirkegaard RH, Dueholm MS, Fernando E, Karst SM, Albertsen M, Nielsen PH. Culture-independent analyses reveal novel anaerolineaceae as abundant primary fermenters in anaerobic digesters treating waste activated sludge. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1134.

Chouari R, Le Paslier D, Daegelen P, Ginestet P, Weissenbach J, Sghir A. Novel predominant archaeal and bacterial groups revealed by molecular analysis of an anaerobic sludge digester. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7(8):1104–15.

Ivanova N, Rohde C, Munk C, Nolan M, Lucas S, Del Rio TG, Tice H, Deshpande S, Cheng JF, Tapia R, et al. Complete genome sequence of Truepera radiovictrix type strain (RQ-24). Standards Genomic Sci. 2011;4(1):91–9.

Anguita-Maeso M, Estudillo-Cazorla C, León-Ropero G, Navas-Cortés JA, de Menezes A, Landa BB: Co-occurrence network inference analysis allows identification of keystone microbial species associated to soil compartments and environments in cultivated olive. In: EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts: 2021; 2021: EGU21-2893.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to WYY for his participation in the collection of samples.

Funding

This work was supported by the Doctor Launch Project of Yibin University (No. 2019QD09 and No. 2019QD10) and partly supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA 20050201) and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (2019QZKK05010105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TZG, YTK, HXL and GP conceived the project and GP, TZG, CDD, ZLL and HXL obtained the funding. YTK, TZG and HXL wrote the paper. TZG, PHL, ZJ, ZX and LGM performed the experiments and data analysis. WYY, LK and YM performed sample collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our experimental procedures complied with the current laws of China for the care and use of experimental animals and were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Yibin University. All applicable international, national and institutional guidelines for animal care and use were observed. All the procedures were conducted according to the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of Experiment Animals Committee affiliated to Yibin University, Yibin, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Z., Pu, H., Cai, D. et al. Characterization of the bacterial microbiota in different gut and oral compartments of splendid japalure (Japalura sensu lato). BMC Vet Res 18, 205 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03300-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03300-w