Abstract

Background

Atlantoaxial instability (AAI) is primarily a congenital neurological disorder affecting young toy-breed dogs. So far, most studies have focused on bones and ligaments related to AAI, and there are no studies on the suboccipital muscles (SOMs) that occupy a large area from the occipital bone to C2 in dogs. This study evaluated the cross-sectional area (CSA) and fat infiltration of the SOMs using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically, T1-weighted images, in normal dogs (≤ 5 kg) and AAI dogs. The relationship between the severity of the neurological symptoms of AAI (group A and group B) and the values from MRI was also assessed.

Results

AAI dogs had significantly smaller CSA (P = 0.029) and greater fat infiltration (P = 0.044) of the SOMs compared to normal dogs. AAI dogs with mild neurological symptoms for a long period (group A) had greater fat infiltration than AAI dogs with severe neurological symptoms (group B) (P = 0.035).

Conclusions

The muscle changes are most likely due to spinal cord compression resulting from instability; however, the possibility that chronic changes of the muscle may play an additional role in maintaining stability in this region cannot be excluded. This study provides fundamental quantitative information of the SOMs in normal and AAI dogs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atlantoaxial instability (AAI) is primarily a congenital neurological disorder affecting young toy-breed dogs, including Maltese, Chihuahua, Toy Poodle, Pomeranian, and Yorkshire Terrier [1]. Several reports describe aetiologies for AAI, including congenital or developmental causes associated with aplasia of the dens, non-union of the ossification centres, and absence of ligamentous support in toy-breed dogs, as well as trauma associated with a fracture of the dens and/or disruption of the ligamentous support in any breed of dog of any age [2, 3].

Since the occipital region of the skull and the first two cervical vertebrae (C1 and C2) develop together embryologically, many dogs are subject to multiple developmental disorders such as caudal occipital malformation syndrome and hypoplasia, atlanto-occipital overlapping, and AAI [4]. Due to its rotational movements, and to the lesser extent of lateral bending with the absence of an intervertebral disc, the atlantoaxial joint (AAJ) requires additional stabilization by suboccipital muscles (SOMs), cervical fasciae and ligamentous structures [5, 6]. Therefore, recently, more specific studies about concurrent diseases with AAI and biomechanical evaluation of the stabilizing function in this region have been conducted [6,7,8,9].

Human studies have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate the cross-sectional area (CSA) and fat infiltration of the SOMs to design effective management strategies for upper neck problems [10,11,12]. Similar studies have been conducted on the thoracolumbar (TL) epaxial muscles in veterinary medicine [13, 14], however, no studies have evaluated the SOMs occupying a large area of this region from the occipital bone to C2 in dogs using MRI.

We hypothesized that there would be a difference in the CSA and fat infiltration of the SOMs between normal dogs and AAI dogs because these muscles may also play a role in stabilizing in AAJ. Among AAI patients, these values could vary, depending on the severity of neurological symptoms. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the CSA and fat infiltration of SOMs using MRI in normal dogs (≤ 5 kg) and AAI dogs, specifically to identify whether there are differences in these values between normal and AAI dogs, and whether these values vary depending on the severity of the AAI symptoms.

Results

Two groups of small dogs (≤ 5 kg, 26 dogs) were included in the study; the first group consisted of 13 normal dogs and the second consisted of 13 dogs with AAI. The mean age and weight of AAI and control dogs and significant differences between groups are displayed in Table 1.

All dogs were of toy-breeds, and Maltese was the most common breed in AAI dogs. Normal dogs weighed more than AAI dogs (P = 0.005). The AAI dogs were also split into two groups based on severity of the neurological symptoms, where group A (mild symptoms) of AAI dogs were older than group B (severe symptoms) (P = 0.001). The duration of neurological symptoms before admission ranged from two days to 4.5 years. The duration of group A (mean: 1.35 years, range: two months to 4.5 years) was longer than that of group B (mean: 130 days, range: two days to six months) (P = 0.008). A history of trauma was reported in two dogs. Abnormalities of the dens were identified in eight dogs, and seven of these showed congenital anomalies.

The measurements of SOMs are summarized in Table 2. Total CSA of the SOMs (P = 0.027) and CSA of the atlas (P = 0.01) increased as the weight of normal dogs increased. However, there was no correlation between body weight and the CSA ratio of SOMs in normal dogs (P = 0.268). The CSA ratio of SOMs (ratio of the CSA of the SOMs to the atlas) between normal and AAI dogs was significantly different (P = 0.029), but there was no statistical significance between the AAI groups (P = 0.836). There were statistical differences in the fat ratio of SOMs (ratio of the intensity of the SOMs to fat) between normal and AAI dogs (P = 0.044), and between AAI groups (P = 0.035) (Fig. 1). There was no significant correlation between the duration of neurological symptoms and the CSA ratio of SOMs (P = 0.951), or between the duration of neurological symptoms and the fat ratio of SOMs (P = 0.245), in AAI dogs. The ratio of spinal cord (ratio of the spinal cord to the canal) between normal and AAI dogs was significantly different (P = 0.001), but there was no significant difference between the AAI groups (P = 0.836). There was no statistical significance in the correlation between the ratio of spinal cord and the CSA ratio of SOMs, or between the ratio of spinal cord and the fat ratio of SOMs in AAI dogs. There was no correlation between all muscle parameters and age, and there were no significant differences between sexes in all groups.

Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) regarding measurements was excellent (CSA of the spinal canal: 0.90–0.99; CSA of the spinal cord: 0.96–0.99; CSA of SOMs: 0.93–0.99; intensity of SOMs: 0.99).

Discussion

The SOMs are three groups of short muscles that cover all surfaces of the atlas and axis. In dogs, the SOMs consists of rectus capitis dorsalis, oblique capitis caudalis, and oblique capitis cranialis [15]. Contraction of the rectus capitis dorsalis and the obliquus capitis cranialis muscles results in an extension of the head. The obliquus capitis caudalis muscle, which attaches laterally to the atlas wings and extends cranially to the spinous process of the axis, is one of the main muscles allowing rotation of the AAJ [16]. As they contribute to the movement of the AAJ, they could affect the stability in this region, and be affected by diseases affecting it.

In this study, the SOMs of AAI dogs appeared smaller and showed increased fat infiltration as compared to those of normal dogs, similar to the results from human studies on the relationship between pain and muscles [10]. This is also consistent with the findings on the epaxial muscles of the TL region in dogs [13]. The smaller SOMs in AAI dogs could be a sign of denervation atrophy; the painful and compressive characteristics and increased fat infiltration into the muscles is likely due to disuse and denervation [13, 17]. However, there is a disagreement between human studies on the influence of pain on muscles; for example, Yuan et al. (2017) reported a relationship between hypertrophy of this muscle and chronic headaches, while Hvedstrup et al. (2020) reported no association between pain and muscle properties [12, 18]. Skeletal muscles and bone share common embryological origins from mesodermal cell populations [19], and it has been reported that congenital abnormalities of bones in this region, such as incomplete ossification of the atlas, are associated with AAI [20]; therefore, it is possible that AAI dogs have congenital abnormalities of the SOMs as well as the bones.

Previous studies in dogs have reported that the severity of clinical symptoms had a significant effect on fat infiltration [13]. However, in this study, among AAI dogs, fat infiltration was more severe in group A dogs with mild symptoms than in group B dogs with severe symptoms. It has been reported that fat infiltration in epaxial muscles increases with age in dogs [21]. In this study, group A was significantly older (7.58 years ± 3.08) than group B (2.56 years ± 1.49, P = 0.001). Therefore, it is possible that the fat infiltration identified in group A is age related, rather than associated with AAI. Although this study only evaluated a small number of dogs, there was no correlation between the fat ratio of muscles and age. In the long term, ongoing effects of pain and inflammatory mechanisms exert additional effects on muscle structure, such as atrophy, fatty infiltration, fibrosis, and function [22]. It is possible that these chronically altered SOMs reduce movement in AAJ, so that group A dogs showed mild symptoms for a long time, despite the AAI. To confirm this possibility, future studies are required to compare the histology of SOMs between normal and AAI dogs. However, intramuscular fat is reliably quantified using the signal intensity obtained by MRI [13, 14, 23]. The T1 relaxation time for fat tissue is short, and the signal intensity is high compared with skeletal muscle on the T1-weighted images; therefore, fat appears hyperintense relative to muscle, which is hypointense [23]. T1-weighted images have been used successfully to evaluate fat infiltration into various muscles in humans and dogs [13, 24,25,26]. Moreover, it has reported that increased fat infiltration and decreased muscle volume on T1-weighted images correlated well with subsequent histological analysis in isolated skeletal muscles of dogs [27]. Therefore, although histological confirmation was not possible, the method of quantifying fat infiltration used in this study may be useful as an index to non-invasively evaluate changes of the SOMs in AAI dogs.

There was no difference in the CSA of the muscle between the AAI groups in this study. It has been reported that nerve lesions affecting the multifidus CSA atrophy progress within three days [28]; most AAI dogs in this study showed neurological symptoms for more than three days; therefore, the possibility that there is no significant difference in the CSA of muscles in the AAI groups was considered.

This study identified a difference in the ratio of spinal cord between normal and AAI dogs. The spinal cord compression in AAI dogs may have affected atrophy and fat infiltration in the SOMs, similar to the results on the epaxial muscles in dogs [13]. However, the correlations between spinal cord compression and muscle atrophy, and between spinal cord compression and fat infiltration in AAI dogs were not statistically significant. A study on humans suggested that the degree of instability in AAI can be underestimated by MRI when compared with radiology [29]. All MRI in this study were taken in a neutral, not a flexed position; therefore, it is highly likely that spinal cord compression due to the degree of instability was not reflected in the measurement.

The main limitation of this study was that the number of dogs in each group was small, and therefore, we used a non-parametric test. Future studies are required with larger groups to investigate the SOMs in dogs. Due to ethical reasons, we were unable to conduct a subsequent histological verification for the muscle changes identified by MRI. In this study, intra-class reproducibility was verified; however, there was no inter-class reproducibility verification because an assessor requires training on MRI images and SOM anatomy for a significant time period. In this regard, further research related to inter-class verification according to the training level is needed for measurement of the muscles. Since the increase in the CSA of the SOMs according to body weight was identified even within toy-breed dogs with ≤ 5 kg, to compensate for possible discrepancies in body weight, the size of the SOMs was evaluated using the CSA ratio of muscles, which was not correlated with body weight because the disc measurement method used in other studies cannot be used in this area [13]. Despite the above limitations, this study provides fundamental quantitative information about MRI of the SOMs in normal and AAI dogs.

Conclusions

This study found that AAI dogs had significantly smaller CSA of the SOMs and greater fat infiltration in the muscles compared to normal dogs. AAI dogs with mild neurological symptoms for a long period had greater fat infiltration in the muscles compared to AAI dogs with severe neurological symptoms. The muscle changes are most likely due to spinal cord compression from instability, however, since the possibility that chronic changes of the muscle may play an additional role in maintaining stability in this region cannot be excluded, larger group studies and histological studies of the muscles are needed. This study provides fundamental quantitative information of the SOMs in normal and AAI dogs.

Methods

Two groups of client-owned small dogs (≤ 5 kg) admitted to Time Animal Hospital (Daejeon, South Korea) from March 2020 to June 2021 were prospectively studied. The first group consisted of 13 normal dogs that were defined as healthy based on physical, complete blood cell (CBC) counts, serum biochemistry, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analyses. None of these dogs showed cervical neurological symptoms. The dogs were normal, except for some with vision loss or presumptively idiopathic seizures. The second group of dogs included 13 dogs with AAI. Physical and neurological examinations, CBC counts, and serum biochemical analyses were also performed in all AAI dogs. To confirm the abnormality of the dens, computed tomography examination was also performed for all AAI dogs. The time of onset of the clinical signs and severity was recorded. By use of a grading system [30], the neurological status of the AAI dogs was graded from 1 to 5 as follows: grade 1: no neurological impairment; grade 2: ambulatory with paresis; grade 3: non-ambulatory paresis; grade 4: quadriplegia and grade 5: dead. A comparison between AAI dogs was made by dividing them into two groups: group A (mild symptoms, grades 1–2) and group B (severe symptoms, grades 3–5).

Cervical MRI examinations were performed with a 1.5-Tesla (Intera, Philips Healthcare, Netherlands) system under general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia was induced in each dog with intravenous propofol (6 mg/kg, Provive 1%, Myungmoon Pharm. Co., Korea) and maintained with isoflurane (Ifran, Hana Pharm., Korea) and oxygen. Dogs were positioned in ventral recumbency, with the forelimbs pulled caudally and a straight spinal alignment, without any pressure on the cervical muscles on the eight-channel knee coil. Transverse MRI settings for measurements were as follows: slice thickness of 2.0 mm, gap of 0.2 mm, T1 weighted (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 10 ms) and T2 weighted (TR = 3000–4000 ms; TE = 100 ms). Dorsal and sagittal T2-weighted and sagittal T1-weighted images were also obtained of the surrounding structures, for reference.

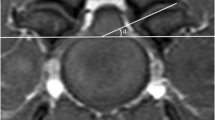

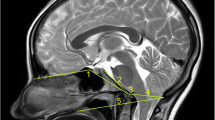

Images were analysed via picture archiving and the use of a communication system (PACSPLUS, Medical Standard, Korea). Measurements followed the methods described in previous reports on dogs and humans [13, 23, 31]. On the transverse T-weighted images, the CSAs of the SOMs (sum of rectus capitis dorsalis, oblique capitis caudalis, and oblique capitis cranialis) were measured bilaterally at C1-2 by manually drawing a region of interest (ROI), tracing the outer margin of the muscles (Fig. 2). The muscles were traced based on the visible bony landmarks, canine anatomy literature [32,33,34,35] and a previous anatomic MRI study of this region [36]. Possible intermuscular fat was excluded. When the boundary between the SOMs and other muscles (semispinalis and longissimus muscle) was unclear, the ROI was defined through the middle of these regions to allow a reasonable approximation of the muscle’s anticipated boundary [37]. Total CSA of the SOMs was calculated by summing the bilateral measurements. To compensate for possible discrepancies in body weight, the CSA of the atlas (C1) was traced based on the outer margin of the atlas body on the same images, and the ratio of the CSA of the SOMs to the atlas (CSA ratio of SOMs) was calculated by dividing the total CSA of the bilateral muscles by the CSA of the atlas. To evaluate presumptive fat infiltration in the muscles, the signal intensity of the muscles was measured from the same ROIs, and the signal intensity of fat (approximately 2 mm2) was also measured at the whitest spot (hyperintense) on the same T1-weighted images (Fig. 2). Ratio of the intensity of the SOMs (mean intensity of bilateral muscles) to fat (fat ratio of SOMs) was calculated by dividing the intensity of the muscles by the intensity of the fat. To evaluate the relationship between the degree of compression of the spinal cord and these values, the ratio of the spinal cord to the canal (ratio of spinal cord) was determined by dividing the CSA of the spinal cord by the CSA of the spinal canal (CSF column) on the transverse T2-weighted images, with reference to the T1-weighted images (Fig. 3).

The measurements of the CSA and the intensity of SOMs and the intensity of fat on the left side at C1-2 in a normal dog. Manually traced ROI: the CSA of the SOMs (orange line) and the CSA of atlas (red line). The ratio of the intensity of muscle to fat was calculated by dividing the intensity of the muscle (black arrow) by the intensity of the fat (white arrow): 556/1768 = 0.31

The CSA of the spinal canal (CSF column) and cord in a normal dog (A, B) and an AAI dog (C, D). On the transverse T2-weighted images (B, D), CSA of the spinal canal (outer line) and CSA of the spinal cord (inner line) were measured at C1-2 level of the corresponding of line at the sagittal T2-weighted images (A, C)

The values were measured three times at an interval of one week, and the assessor (NS Lee) was blinded to the earlier values.

Statistical analyses of the data were performed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 22, IBM Corporation, USA). Kendall’s Tau was used to identify the significant correlations between the values and body weight, age, the compression rate, and the duration of neurological symptoms. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare between the values of normal and AAI dogs, and between the values of the groups within AAI and sex. Reproducibility was assessed using the ICC: a value close to 1 indicates excellent agreement. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

01 March 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03177-9

Abbreviations

- AAI:

-

Atlantoaxial instability

- AAJ:

-

Atlantoaxial joint

- SOMs:

-

Suboccipital muscles

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CSA:

-

Cross-sectional area

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

- TL:

-

Thoracolumbar

- CBC:

-

Complete blood cell

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

References

Slanina MC. Atlantoaxial instability. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2016;46:265–275.

Oliver JE, Lewis RE. Lesions of the atlas and axis in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 1973;9:304–313.

Watson AG, de Lahunta A. Atlantoaxial subluxation and absence of transverse ligament of the atlas in a dog. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1989;195:235–237.

Dewey CW, Marino DJ, Loughin CA. Craniocervical junction abnormalities in dogs. N. Z. Vet. J. 2013;61:202–211.

Steinmetz MP, Mroz TE, Benzel EC. Craniovertebral junction: biomechanical considerations. J. Neurosurg. 2010;66:7–12.

Planchamp B, Bluteau J, Stoffel MH, Precht C, Schmidli F, Forterre F. Morphometric and functional study of the canine atlantoaxial joint. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;128:76–85.

Kupczynska M, Wieladek A, Janczyk P. Craniocervical junction in dogs revisited–new ligaments and confirmed presence of enthesis fibrocartilage. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012;92:356–361.

Forterre F, Precht C, Riedinger B, Bürki A. Biomechanical properties of the atlantoaxial joint with naturally-occurring instability in a toy breed dog. A comparative descriptive cadaveric study. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2015;28:355–358.

Riedinger B, Bürki A, Stahl C, Howard J, Forterrem F. Biomechanical evaluation of the stabilizing function of three atlantoaxial implants under shear loading: a canine cadaveric study. Vet. Surg. 2015;44:957–963.

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cuadrado ML, Arendt-Nielsen L, Ge HY, Pareja JA. Association of cross-sectional area of the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle with active trigger points in chronic tension-type headache: a pilot study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008;7:197–203.

Fakhran S, Qu C, Alhilali LM. Effect of the suboccipital musculature on symptom severity and recovery after mild traumatic brain injury. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1556–1560.

Yuan XY, Yu SB, Liu C, Xu Q, Zheng N, Zhang JF, Chi YY, Wang XG, Lin XT, Sui HJ. Correlation between chronic headaches and the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle: a comparative analysis of cross-sectional trail. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:1051–1056.

Boström AF, Hielm-Björkman AK, Chang YM, Weller R, Davies ES. Comparison of cross sectional area and fat infiltration of the epaxial muscles in dogs with and without spinal cord compression. Res. Vet. Sci. 2014;97:646–651.

Beale CC, Secrest SA. MRI assessment of epaxial myosteatosis in dogs with intervertebral disc extrusions and associations with patient factors and outcome. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2021;62:687-696.

Sharir A, Milgram J, Shahar R. Structural and functional anatomy of the neck musculature of the dog (Canis familiaris). J. Anat. 2006;208:331–351.

König HE, Liebich H-G, editors. Fasciae and muscles of the head, neck and trunk. In: Veterinary Anatomy of Domestic Animals: Textbook and Color Atlas, 7nd ed. Thieme, Stuttgart; 2020. p. 125–135.

Hyun JK, Lee JY, Lee SJ, Jeon JY. Asymmetric atrophy of multifidus muscle in patients with unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathy. Spine. 2007;32:E598-602.

Hvedstrup J, Amin FM, Hougaard A, Ashina H, Christensen CE, Larsson HBW, Ashina M, Schytz HW. Volume of the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle in migraine patients: a cross-sectional structural MRI study. J. Headache Pain. 2020;21:57.

Hamrick MW, McGee-Lawrence ME, Frechette DM. Fatty infiltration of skeletal muscle: mechanisms and comparisons with bone marrow adiposity. Front. Endocrinol. 2016;7:69.

Parry AT, Upjohn MM, Schlegl K, Kneissl S, Lamb CR. Computed tomography variations in morphology of the canine atlas in dogs with and without atlantoaxial subluxation. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound. 2010;51:596–600.

Sutherland-Smith J, Hutchinson D, Freeman LM. Comparison of computed tomographic attenuation values for epaxial muscles in old and young dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2019;80:174-177.

Hodges PW, Danneels L. Changes in structure and function of the back muscles in low back pain: different time points, observations, and mechanisms. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019;49:464–476.

Elliott JM, Galloway GJ, Jull GA, Noteboom JT, Centeno CJ, Gibbon WW. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of the upper cervical spine extensor musculature in an asymptomatic cohort: an index of fat within muscle. Clin. Radiol. 2005;60:355–363.

Elliott J, Sterling M, Noteboom JT, Darnell R, Galloway G, Jull G. Fatty infiltrate in the cervical extensor muscles is not a feature of chronic, insidious-onset neck pain. Clin. Radiol. 2008;63:681–687.

Cagnie B, Barbe T, Vandemaele P, Achten E, Cambier D, Danneels L. MRI analysis of muscle/fat index of the superficial and deep neck muscles in an asymptomatic cohort. Eur. Spine J. 2009;18:704–709.

Davis DL, Kesler T, Gilotra MN, Almardawi R, Hasan SA, Gullapalli RP, Zhuo J. Quantification of shoulder muscle intramuscular fatty infiltration on T1-weighted MRI: a viable alternative to the Goutallier classification system. Skelet. Radiol. 2019;48:535–541.

Safran O, Derwin KA, Powell K, Iannotti JP. Changes in rotator cuff muscle volume, fat content, and passive mechanics after chronic detachment in a canine model. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:2662–2670.

Hodges P, Holm AK, Hansson T, Holm S. Rapid atrophy of the lumbar multifidus follows experimental disc or nerve root injury. Spine. 2006;31(25):2926–2933.

Laiho K, Soini I, Kautiainen H, Kauppi M. Can we rely on magnetic resonance imaging when evaluating unstable atlantoaxial subluxation? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003;62:254–256.

Beaver DP, Ellison GW, Lewis DD, Goring RL, Kubilis PS, Barchard C. Risk factors affecting the outcome of surgery for atlantoaxial subluxation in dogs: 46 cases (1978–1998). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000;216:1104–1109.

Ulbrich EJ, Schraner C, Boesch C, Hodler J, Busato A, Anderson SE, Eigenheer S, Zimmermann H, Sturzenegger M. Normative MR cervical spinal canal dimensions. Radiology. 2014;271:172–182.

George TF, Smallwood JE. Anatomic atlas for computed tomography in the mesaticephalic dog: head and neck. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound. 1992;33:217–240.

Boyd JS, Paterson C, May AH. Head and neck, In: Color atlas of clinical Anatomy of the Dog & Cat. 2nd ed. Harcourt Publishers Limited, Jamestown Road; 2001. p. 55–82.

Budras KD, McCarthy PH, Fricke W, Richter R, Horowitz A, Berg R. Neck and chest region, In: Anatomy of the Dog: An Illustrated Text. 5nd ed. Schluetersche, Hannover; 2007. p. 12–14.

Evans HE, de Lahunta A. The muscular system, In: Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog. 4nd ed. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO; 2013. p. 209–210.

Alizadeh M, Zindl C, Allen MJ, Knapik GG, Fitzpatrick N, Marras WS. MRI cross sectional atlas of normal canine cervical musculoskeletal structure. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016;109:94–100.

Fortin M, Battié MC. Quantitative paraspinal muscle measurements: inter-software reliability and agreement using OsiriX and ImageJ. Phys Ther. 2012;92:853–64.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Time Animal Medical Center for their assistance.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL: contributed to the conception, design of the work and data acquisition, analyzed and interpreted the patient data, was a major contributor in writing the manuscript; MY: contributed to data acquisition, substantively revised the manuscript; JY: contributed to the conception, design of the work and substantively revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocols were approved by the Seoul National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval number SNU-210702-2). All experiments were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines and regulations, and the study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. A written consent from the owners was taken

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: the authors spotted the error pertaining to mismatched figure images and captions/legends.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, N., Yun, M. & Yoon, J. Comparison of cross-sectional area and fat infiltration of suboccipital muscles between normal dogs and dogs with atlantoaxial instability. BMC Vet Res 18, 46 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-03132-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-03132-0