Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is a frequent colonizer of human and several animal species, including dairy cows. It is the most common cause of intramammary infections in dairy cows. Its public health importance increases inline to the continuous emergence of drug-resistant strains; such as Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Indeed, the recent emergence of human and veterinary adapted MRSA demands serious attention. The aim of this study was to determine the burden and drug resistance pattern of S. aureus in dairy farms in Mekelle and determine the molecular characteristics of MRSA.

Results

This study was done on 385 lactating dairy cows and 71 dairy farmers. The ages of the cows and farmworkers were between 3 and 14 and 17–63 years respectively. S. aureus was isolated from 12.5% of cows and 31% of farmworkers. Highest resistance was observed for penicillin (> 90%) followed by tetracycline (32–35%) and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (10–27%). But no resistance was observed for vancomycin, daptomycin, and rifampin. Only one isolate was MRSA both phenotypically and harboring mecA. This isolate was from nasal of a farmworker and was MRSA SCCmec Iva, spa type t064 of CC8. Multi-drug resistance was observed in 6.2% of cow isolates and 13.6% of nasal isolates.

Conclusions

In this study, S. aureus infected 12.5% of dairy cows and colonized 31% of farmworkers. Except for penicillin, resistance to other drugs was rare. Although no MRSA was found from dairy cows the existence of the human and animal adapted and globally spread strain, MRSA SCCmec IVa spa t064, warrants for a coordinated action to tackle AMR in both human and veterinary in the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus causes a diverse array of diseases in both human and animals, including dairy cows. Human infections range from mild skin infections to life-threatening ones; such as bacteremia, endocarditis, necrotizing pneumonia and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) [1]. The major diseases in animals include mastitis (infection of the intramammary gland) in dairy cows, joint infections in poultry and surgical site infections equine [2]. Intramammary infections of dairy cows negatively affect the dairy industry due to poor milk yields, veterinary treatments, and milk that must be discarded [3]. Besides causing diseases, S. aureus commonly colonizes and lives harmlessly in different body parts of human and animals. About half of healthy human individuals are thought to be colonized persistently or transiently [2] with the most common sites being the anterior nares [4]. The teat skin, rectum or nasal cavity of dairy cows are also commonly colonized by S. aureus [3]. S. aureus transmission in dairy cattle is thought to occur primarily via milking machine, udder cloths or milkers’ hands [5].

S. aureus is a highly adaptive pathogen which continuously evolves resistance to most of the available antibiotics [6]. The best example is the emergence and spread of MRSA initially in the healthcare setting later in the community among relatively young and healthy individuals [7] and recently in livestock and people having occupational contact with these animals [4]. Factors leading to drug resistance in S. aureus include acquisition of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) carrying resistance genes [8] and improper use of drugs. Antimicrobial use in food-producing animals for growth promotion and/or treatment purpose is facilitating the selection and spread of resistant bacteria in these animals. Such bacteria could be transmitted to humans via food and other transmission routes [9, 10].

Methicillin resistance is caused by the acquisition of the mecA or mecC gene in the mobile genetic element called SCCmec. Both of the mec genes code for alternative penicillin-binding proteins, PBP2a, that has reduced affinity to most β-lactam antibiotics [11]. Traditionally, most MRSA strains are known to have specific host tropism. However, recent reports showed that some strains are losing their specificity and be easily transmitted from animals to humans or vice-versa [12]. For example, the MRSA of ST1-SCCmec IV which have been known to be associated with community-acquired infections in a human was isolated from dairy cows with mastitis in Australia [13] and Italy [14]. In addition, the epidemic human strain, UK-EMRSA-15 of CC22, was demonstrated recently in intramammary infections of dairy cows in Italy [12]. Livestock acquired (LA) MRSA due to mecC, which has spread extensively in livestock animals, has emerged recently among high-risk groups who have occupational contact with these animals [4].

In Ethiopia, there is strong research-based evidence showing S. aureus as an important udder pathogen in dairy cows [15,16,17,18]. However, whether mecA/mecC harbouring S. aureus strains are associated with dairy cows infection is not well explored. So far, two studies by Tigabu et al. [19] and Mekonnen et al. [20] attempted to detect mecA positive strains from dairy milk but neither found it. However, it should be noted that both studies targeted only mecA but not mecC (another gene responsible for methicillin resistance). As to our knowledge, study to detect MRSA from dairy cows and farmworkers to demonstrate the existence of adapted strains hasn’t been conducted so far in Ethiopia.

Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the burden of S. aureus and its drug resistance pattern in dairy cows and farmworkers and study the molecular characteristics of MRSA.

Results

In this study a total of 385 lactating dairy cows and 71 dairy farm workers from 67 dairy farms located in 3 sub-cities of Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia were studied.

The cows’ age ranged from 3 to 14 years with a mean age of 5.9 years. Majority of them were within the age group of 3–5 years (178/385, 46.2%). The parity of the cows ranged from 1 to 11 where two-third (254/385, 66%) of them gave birth to 1–3 calves. More than half of the cows (203/385, 52.7%) had less than 3 months of lactation stage. In all the dairy farms the milking process was done by manual method (Table 1).

Regarding the dairy farmworkers, more than three fourth (55/71, 77.5%) were males and their age ranged from 17 to 63 years with the mean age of 29 years. They had a work experience of up to 40 years in the current farm (Table 2).

The isolation rate of Staphylococcus aureus

S. aureus was initially identified by biochemical methods and confirmed by nuc gene detection. Accordingly, 12.5% (48/385) of udder quarters of dairy cows and 31% (22/71) of nares of dairy farm workers harbored S. aureus.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates

Milk isolates showed the highest resistance for penicillin (44/48, 91.7%) followed by tetracycline (17/48, 35.4%) and trimethoprim-Sulphamethoxazole (5/48, 10.4%). No MRSA was isolated from the milk of the dairy cows (Table 3). Similarly, nasal isolates also showed the highest resistance for penicillin (20/22, 90.9%) followed by tetracycline (7/22, 31.8%) and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (6/22, 27.3%). One MRSA isolate was documented on a dairy farmer as determined phenotypically by Cefoxitin disk diffusion method. Phenotypically MRSA isolate was not found from the dairy cows. In addition, no resistance was observed for vancomycin, daptomycin, and rifampin in both the milk and nasal isolates (Table 3).

Overall, 46/48 (95.8%) of the milk isolates were resistant to at least one of the nine antimicrobial agents where 29/48(60.4%) were resistant to only one, 14/48 (29.2%) to two and 3/48 (6.2%) were multi-drug resistant (resistant to three or more drugs in different classes). Regarding the nasal isolates, 20/22 (90.9%) were resistant to at least one, 7/22 (31.8%) to only one, 10/22 (45.5%) to two and 3/22 (13.6%) were MDR.

Molecular characterization of isolates

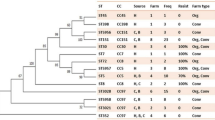

All the 70 isolates from cows’ udder quartes (48 isolates) and farmers’ nares (22 isolates) were tested for their mecA and mecC possession. Only one isolate from the nasal of a farmworker was found positive for mecA. No mecA was documented from the cows. In addition, All the human and cow isolates were negative for mecC. Further characterization of the mecA positive S. aureus isolates revealed that it was spa type t064 and SCCmec type Iva. Based on the spa sequence this was in the clonal complex 8 (CC8).

Discussion

Staphylococcus aureus commonly colonizes various body parts of human and dairy cows that can lead to a diverse array of diseases [2]. Intramammary infection in dairy cows is common resulting in significant economic loss to farmers due to decreased milk production or abnormal milk that must be discarded [3]. Furthermore, consumption of milk obtained from infected dairy cows by a human can lead to infections or intoxications by toxins produced by S. aureus [21, 22]. The emergence of drug-resistant strains, such as MRSA, in both animals and human with the ability of cross-transmission between them, is of special concern [4]. S. aureus human and animal cross-transmission is well demonstrated between dairy cattle and farm workers due to their close contact [23]. Hands of such farmers appear to be the primary transmitters of S. aureus to the dairy cows during milking [5]. As to our knowledge, there is only one research report on S. aureus from both dairy cows and farmers in Ethiopia [24] unlike the several studies conducted on dairy cows. Indeed, this study was limited to phenotypic characterization only. Hence, the present study was conducted on 71 farm workers and 385 dairy cows obtained from 67 dairy farms located in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia to determine the burden and resistance of S. aureus and consequently study the molecular characteristics of MRSA.

In the present study, 31% of dairy farmers were found colonized by S. aureus in their nares which is higher than a previous study done around Addis Ababa, Ethiopia where 13.2% of dairy farmers were found colonized [24]. In the present study, tryptic soy broth as an enrichment media was used to maximize the recovery of S. aureus from nasal swabs and this might explain the higher frequency of isolation as compared to the similar study conducted in Ethiopia [24]. Studies from other parts of the world also showed a significant nasal carriage of S. aureus from farmworkers; 15.2% of dairy farm workers carried S. aureus in their nares in South Africa [25] and 36% in Catania, Italy [26].

In the present study, milk samples from 12.5% of dairy cows yielded S. aureus. Similarly, previous studies in Ethiopia also reported an S. aureus prevalence of 9 to 27.9% [24, 27,28,29]. Other studies in Western Zambia [30], Zimbabwe [31] and Northern Italy [32] have reported an S. aureus isolation rate of 22, 16.3, and 9.1%, respectively from cows’ milk.

The continuous evolution of resistance to most of the available antibiotics by S. aureus is a key public health concern. The first antibiotic-resistant S. aureus was reported for penicillin 2 years after the introduction of the drug [33]. Since then, penicillin-resistant S. aureus has increased and spread widely. Nowadays the majority of S. aureus isolates elsewhere are penicillin-resistant [34]. Previous studies in Ethiopia reported penicillin resistance in 97–100% of S. aureus isolates from dairy cows and farm workers [24, 29]. In agreement, the present study documented penicillin resistance in 91.7 and 90.9% of cow and farmer isolates respectively. However, resistance to other antimicrobials was found either very low or absent in the current study. The respective resistances of dairy cows and farmworkers’ isolates were tetracycline 35.4% and 31.8, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole 10.4 and 27.3% and methicillin 0 and 4.5%. Furthermore, all the isolates were susceptible to vancomycin, daptomycin, and rifampin.

Despite several reports on MRSA from dairy cows elsewhere, the present study didn’t find any isolate harboring mecA/mecC. This is in agreement with the previous studies conducted in central Ethiopia [19], Tunisia [35] and Australia [36]. However, up to 52% MRSA was reported from the milk of dairy cows in Egypt [37, 38], 17% in Turkey [39], 11% in Brazil [40], 9.3% in Belgium [41], 6.2% in Korea [42]. From the present and previous studies in Ethiopia, it is possible that MRSA adapted to the intramammary gland of dairy cows is not circulating. However, the present study recommends the conduct of a nationwide study for a better conclusion. Indeed, Ethiopian has to learn from the other countries with high MRSA burden and implement antimicrobial stewardship program in both human and animals.

Unlike dairy cows, MRSA harboring mecA was found in one (4.5%) of S. aureus isolates from the nares of a dairy farmer. As to our knowledge, this is the first report on mecA positive S. aureus in Ethiopia. Further characterization showed that the strain was MRSA-SCCmec Iva, spa type t064 and in the CC8. This MRSA strain was previously reported from human patients with bacteremia in South Africa [43], nasal and blood of human patients in the USA [44], from a veterinary surgeon from South America [45], goats in the Czech Republic [46], human clinical isolates, horses and veterinary personnel in Ireland [47], horse infections in Germany [48], the Netherlands [49] and Sweden [50]. This highlights MRSA spa t064 harboring SCCmec IVa is an adapted strain to both human and animals with global distribution. As indicated above, this strain is commonly isolated from horse infections and colonization. Hence, future studies should be done to determine its existence in horses in Ethiopia. All the S. aureus isolates will be genotyped in the future to see if there are some strains shared by the dairy cows and farmers.

Conclusions

In the present study, S. aureus was detected in the udders of 12.5% of dairy cows and nares of 31% of farmworkers. The isolates from both cows and farmworkers showed high resistance to Penicillin (> 90%), low resistance to tetracycline and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole but no resistance for vancomycin, daptomycin, and rifampin. This study reported MRSA SCCmec IVa, spa type t064 for the first time in the country. This strain was previously reported from human and veterinary in different parts of the continent. This warrants a coordinated one health approach to contain and prevent the emergence and spread of such drug-resistant microbes in Ethiopia. As it was commonly reported from horses, conducts of future studies to determine whether such animals harbor this strain are strongly recommended in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out in Mekelle, the capital city of the Tigray Regional State, Northern Ethiopia. According to the 2017 report by the central statistical agency of Ethiopia, the cattle population of the region was around 4.8 million where around 2.4 million (51%) were females; among these 28,133 were dairy cows [51].

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2016 to March 2017 to characterize S. aureus isolates from dairy cows and farmworkers.

Study population

This study was done on 385 lactating dairy cows and 71 dairy farmers from 67 Small and large scale dairy farms located in 3 sub-cities of the town; i.e. Hawolti, Semen, and Hadnet. All lactating cows and all available dairy farmworkers during data/sample collection were included.

Data and sample collection

Data regarding sociodemographic characteristics of the dairy cows and farmers were collected using questioner. Also, appropriate laboratory samples from all the study participants were collected.

A nasal swab from dairy farmers

Swabs were collected from both nares of dairy farm workers using BD culture swab (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA). The sterile swab was inserted about 2.5 cm (1 in.) from the edge of the nares and rotated 5 times against the anterior nasal mucosa and repeated with the same swab in the second naris. The nasal swab was then returned to its tube, labeled and transported to the Microbiology laboratory of Ayder Referal Hospital in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia.

Milk from dairy cows

Pooled milk sample was collected from all udder quarters of each lactating dairy cow according to the procedures of the National Mastitis Council. Briefly, the udders of the cow were thoroughly cleaned with water and dried with a clean towel. Then teat ends were disinfected with cotton swabs soaked in 70% alcohol and allowed to air dry. After discarding the first streams; three to four streams of milk (1–2 ml) from each udder quarter (4 × 3 = 12 streams in total from a single cow) were collected into a sterile leak-proof plastic container and transported to the Microbiology laboratory in an icebox.

Culture and identification of S. aureus

All specimens were processed for culture and sensitivity testing. Nasal swabs were initially incubated overnight in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid, Ltd., England) to increase the recovery of S. aureus. Then 10 μl of milk and 100 μl of the broth were each inoculated into blood agar containing 5% sheep blood (Oxoid, Ltd., England) and Mannitol salt agar (Oxoid). The plates were incubated at 35–37 °C in an anaerobic atmosphere for 24 h and then inspected for bacterial growth. Incubation was extended to 48 h if no growth was observed within 24 h. Colonies suspected as S. aureus were sub-cultured into Tryptic soy agar to get pure colonies and were identified as S. aureus based on colony characteristics, Gram stain reaction, hemolysis, catalase test, coagulase test, DNase test, and mannitol fermentation. Phenotypically identified S. aureus isolates were stored in 20% glycerol at − 70 °C until they were shipped to the Ohio State University, the USA for molecular characterization.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was done using disc diffusion technique and E-test according to the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [52]. Briefly, a standardized suspension of each S. aureus isolate was prepared using normal saline standardized using McFarland 0.5. The standardized suspension was streaked on to Muller-Hinton Agar (Oxoid) and allowed to dry. Then, the antibiotic discs or E-test strips were placed on the medium and incubated at 35–37 °C for 16–18 h. The incubation time was extended to 24 h for cefoxitin (30 μg) disc, which was used as a surrogate test for methicillin resistance. After the appropriate incubation time, the zones of inhibition were measured using a caliper and interpreted as sensitive, intermediate and resistant. For the disc diffusion method, the following antimicrobials and disc potencies were used: penicillin (10 IU), cefoxitin (30 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), clindamycin (2 μg), trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg) and rifampin (5 μg). However, susceptibility testing for vancomycin and daptomycin was done using the E-test method. Inducible clindamycin resistance was also determined by double-disk diffusion test (D-test) for erythromycin-resistant but clindamycin susceptible isolates.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood and Tissue extraction kit for gram-positive bacteria (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

PCR was used to confirm the phenotypically identified isolates, detect mecA/mecC and SCCmec typing at the Infectious Diseases Molecular Epidemiology Laboratory (IDMEL), Department of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University, USA. The primer pairs and control strains used are shown in Table 4.

nuc detection: Phenotypically identified S. aureus isolates were confirmed by the detection of the thermonuclear coding gene, nuc according to Brakstad et al. [53] using the illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, USA).

mecA, mecC detection: performed as previously described protocol by Stegger et al. [54] using the illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, USA).

SCCmec typing: SCCmec typing was done according to previously described multiplex PCR by Kondo et al. [55]. All PCR products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis and transilluminator for visualization of bands.

spa typing: was performed for all confirmed S. aureus isolates as previously described protocol [56] at the Public Health Research Institute, International Center for Public Health, The State University of New Jersey, USA. Shortly, the polymorphic X region of the spa gene was amplified by PCR and sequenced. Sequences were analyzed using Ridom Staph-Type software (Ridom GmbH) which detects spa repeats automatically and assigns a spa-type (http://spaserver.ridom.de/).

Data analysis

Data was entered into excel spreadsheet, cleaned and exported to SPSS software version 20 for analysis. P-value < 0.05 was considered as cut off point for the significant association.

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted after approved by the Institutional Review Board (AAU-IRB) of the Colleges of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia and National Research Ethics Review Committee (NERC) of Ministry of Science and Technology, Ethiopia. Also, permission from dairy farm owners/managers was obtained before collection of milk samples. Written informed consent was obtained from each dairy farmer. The aim of the study, its significance, confidentiality, participation right, procedure, and associated risks were explained through an information sheet.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- AST:

-

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

- ATCC:

-

American type culture collection

- CC:

-

Clonal complex

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- MDR:

-

Multi-drug resistance

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PBP:

-

Penicillin binding protein

- PCR:

-

Polymarase chain reaction

- SCCmec :

-

Staphylococcal cassette chromosomes mec

- spa :

-

Staphylococcal protein A

- ST:

-

Sequence type

References

Lin YC, Peterson ML. New insights into the prevention of staphylococcal infections and toxic shock syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:753–67.

Graveland H, Duim B, van Duijkeren E, Heederik D, Wagenaar JA. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals and humans. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:630–4.

Peton V, Le Loir Y. Staphylococcus aureus in veterinary medicine. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:602–15.

Verkade E, Kluytmans J. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus CC398: animal reservoirs and human infections. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:523–30.

Zadoks RN, Middleton JR, McDougall S, Katholm J, Schukken YH. Molecular epidemiology of mastitis pathogens of dairy cattle and comparative relevance to humans. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2011;16:357–72.

Ortega E, Abriouel H, Lucas R, Galvez A. Multiple roles of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: pathogenicity, superantigenic activity, and correlation to antibiotic resistance. Toxins (Basel). 2010;2:2117–31.

Paterson GK, Harrison EM, Holmes MA. The emergence of mecC methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:42–7.

McCarthy AJ, Witney AA, Lindsay JA. Staphylococcus aureus temperate bacteriophage: carriage and horizontal gene transfer is lineage associated. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:6.

Santy-Tomlinson J. Antimicrobial resistance stewardship: it's up to us all. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2018;28:1–3.

WHO. WHO guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Wendlandt S, Fessler AT, Monecke S, Ehricht R, Schwarz S, Kadlec K. The diversity of antimicrobial resistance genes among staphylococci of animal origin. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:338–49.

Magro G, Rebolini M, Beretta D, Piccinini R. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC22-MRSA-IV as an agent of dairy cow intramammary infections. Vet Microbiol. 2018;227:29–33.

Abraham S, Jagoe S, Pang S, Coombs GW, O'Dea M, Kelly J, Khazandi M, Petrovski KR, Trott DJ. Reverse zoonotic transmission of community-associated MRSA ST1-IV to a dairy cow. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50:125–6.

Pilla R, Castiglioni V, Gelain ME, Scanziani E, Lorenzi V, Anjum M, Piccinini R. Long-term study of MRSA ST1, t127 mastitis in a dairy cow. Vet Rec. 2012;170:312.

Abdella M. Bacterial causes of bovine mastitis in Wondogenet, Ethiopia. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1996;43:379–84.

Getahun K, Kelay B, Bekana M, Lobago F. Bovine mastitis and antibiotic resistance patterns in Selalle smallholder dairy farms, central Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2008;40:261–8.

Abera M, Habte T, Aragaw K, Asmare K, Sheferaw D. Major causes of mastitis and associated risk factors in smallholder dairy farms in and around Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:1175–9.

Haftu R, Taddele H, Gugsa G, Kalayou S. Prevalence, bacterial causes, and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of mastitis isolates from cows in large-scale dairy farms of northern Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:1765–71.

Tigabu E, Kassa T, Asrat D, Alemayehu H, Sinmegn T, Adkins PRF, Gebreyes W. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from bovine milk in central highlands of Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2015;9:2209–17.

Mekonnen SA, Lam T, Hoekstra J, Rutten V, Tessema TS, Broens EM, Riesebos AE, Spaninks MP, Koop G. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk samples of dairy cows in small holder farms of North-Western Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:246.

Sartori C, Boss R, Bodmer M, Leuenberger A, Ivanovic I, Graber HU. Sanitation of Staphylococcus aureus genotype B-positive dairy herds: a field study. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:6897–914.

De Vliegher S, Fox LK, Piepers S, McDougall S, Barkema HW. Invited review: mastitis in dairy heifers: nature of the disease, potential impact, prevention, and control. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:1025–40.

Smith TC. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: the United States experience. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004564.

Mekuria A, Asrat D, Woldeamanuel Y, Tefera G. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk samples of dairy cows and nasal swabs of farm workers in selected dairy farms around Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:3501–10.

Schmidt T, Kock MM, Ehlers MM. Diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitis cases and close human contacts. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:6256–69.

Antoci E, Pinzone MR, Nunnari G, Stefani S, Cacopardo B. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among subjects working on bovine dairy farms. Infez Med. 2013;21:125–9.

Mekonnen SA, Koop G, Melkie ST, Getahun CD, Hogeveen H, Lam T. Prevalence of subclinical mastitis and associated risk factors at cow and herd level in dairy farms in north-West Ethiopia. Prev Vet Med. 2017;145:23–31.

Abebe R, Hatiya H, Abera M, Megersa B, Asmare K. Bovine mastitis: prevalence, risk factors and isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy herds at Hawassa milk shed, South Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12:270.

Seyoum B, Kefyalew H, Abera B, Abdela N. Prevalence, risk factors and antimicrobial susceptibility test of Staphylococcus aureus in bovine cross breed mastitic milk in and around Asella town, Oromia regional state, southern Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2018;177:32–6.

Knight-Jones TJ, Hang'ombe MB, Songe MM, Sinkala Y, Grace D. Microbial contamination and hygiene of fresh cow’s Milk produced by smallholders in Western Zambia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:737.

Katsande S, Matope G, Ndengu M, Pfukenyi DM. Prevalence of mastitis in dairy cows from smallholder farms in Zimbabwe. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2013;80:523.

Riva A, Borghi E, Cirasola D, Colmegna S, Borgo F, Amato E, Pontello MM, Morace G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in raw Milk: prevalence, SCCmec typing, enterotoxin characterization, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Food Prot. 2015;78:1142–6.

Deurenberg RH, Stobberingh EE. The evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:747–63.

Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3057–71.

Ben Said M, Abbassi MS, Bianchini V, Sghaier S, Cremonesi P, Romano A, Gualdi V, Hassen A, Luini MV. Genetic characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine milk in Tunisia. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2016;63:473–81.

Worthing KA, Abraham S, Pang S, Coombs GW, Saputra S, Jordan D, Wong HS, Abraham RJ, Trott DJ, Norris JM. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Australian animals and veterinarians. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24:203–12.

Awad A, Ramadan H, Nasr S, Ateya A, Atwa S. Genetic characterization, antimicrobial resistance patterns and virulence determinants of Staphylococcus aureus isolated form bovine mastitis. Pak J Biol Sci. 2017;20:298–305.

Elhaig MM, Selim A. Molecular and bacteriological investigation of subclinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae in domestic bovids from Ismailia, Egypt. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;47:271–6.

Turkyilmaz S, Tekbiyik S, Oryasin E, Bozdogan B. Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine milk. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010;57:197–203.

Silva NC, Guimaraes FF, Manzi MP, Junior AF, Gomez-Sanz E, Gomez P, Langoni H, Rall VL, Torres C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of lineage ST398 as cause of mastitis in cows. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;59:665–9.

Vanderhaeghen W, Cerpentier T, Adriaensen C, Vicca J, Hermans K, Butaye P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST398 associated with clinical and subclinical mastitis in Belgian cows. Vet Microbiol. 2010;144:166–71.

Nam HM, Lee AL, Jung SC, Kim MN, Jang GC, Wee SH, Lim SK. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Korea. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8:231–8.

Perovic O, Singh-Moodley A, Govender NP, Kularatne R, Whitelaw A, Chibabhai V, Naicker P, Mbelle N, Lekalakala R, Quan V, et al. A small proportion of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia, compared to healthcare-associated cases, in two south African provinces. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:2519–32.

Tenover FC, Tickler IA, Goering RV, Kreiswirth BN, Mediavilla JR, Persing DH, Consortium M. Characterization of nasal and blood culture isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in United States hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1324–30.

Post V, Harris LG, Morgenstern M, Geoff Richards R, Sheppard SK, Fintan MT. Characterization of nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from international human and veterinary surgeons. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:360–70.

Tegegne HA, Florianova M, Gelbicova T, Karpiskova R, Kolackova I. Detection and molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bulk tank milk of cows, sheep, and goats. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019;16:68–73.

Abbott Y, Leonard FC, Markey BK. Detection of three distinct genetic lineages in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from animals and veterinary personnel. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:764–71.

Cuny C, Abdelbary MMH, Kock R, Layer F, Scheidemann W, Werner G, Witte W. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from infections in horses in Germany are frequent colonizers of veterinarians but rare among MRSA from infections in humans. One Health. 2016;2:11–7.

van Duijkeren E, Moleman M, Sloet van Oldruitenborgh-Oosterbaan MM, Multem J, Troelstra A, Fluit AC, van Wamel WJ, Houwers DJ, de Neeling AJ, Wagenaar JA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses and horse personnel: an investigation of several outbreaks. Vet Microbiol. 2010;141:96–102.

Bergstrom K, Aspan A, Landen A, Johnston C, Gronlund-Andersson U. The first nosocomial outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in horses in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand. 2012;54:11.

CSA. Agricultural sample survey: report on livestock and livestock characteristics. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Stat Bull. 2017;II:38–50.

CLSI. M100-S25 - performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement. Clin Lab Stand Inst. 2015;35:64–70.

Brakstad OG, Aasbakk K, Maeland JA. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1654–60.

Stegger M, Andersen PS, Kearns A, Pichon B, Holmes MA, Edwards G, Laurent F, Teale C, Skov R, Larsen AR. Rapid detection, differentiation and typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harbouring either mecA or the new mecA homologue mecA (LGA251). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:395–400.

Kondo Y, Ito T, Ma XX, Watanabe S, Kreiswirth BN, Etienne J, Hiramatsu K. Combination of multiplex PCRs for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment: rapid identification system for mec, ccr, and major differences in junkyard regions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:264–74.

Shopsin B, Gomez M, Montgomery SO, Smith DH, Waddington M, Dodge DE, Bost DA, Riehman M, Naidich S, Kreiswirth BN. Evaluation of protein a gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3556–63.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by Addis Ababa University and Aksum University. The nuc PCR, mecA/MecC PCR, and SCCmec typing were supported by the Ohio State University. We thank Dr. Barry Kreiswirth and Mr. José Mediavilla at the Public Health Research Institute of the State University of New Jersey, USA for generously conducted spa typing of MRSA isolate.

Funding

This study was supported by Addis Ababa University, Aksum University and the Ohio State University. The universities had no role on design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAK, DAW, YWM, SHW and WAG participated in analysis and write-up of the proposal and manuscript. AAK was also the major contributor in the laboratory investigation. TT involved during data collection and write up of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted after gaining full approval by the Institutional Review Board (AAU-IRB) of the Colleges of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia and The Ethiopian National Research Ethics Review Committee (NERC). Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Also, permission from dairy farm owners/managers was obtained before collection of milk samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalayu, A.A., Woldetsadik, D.A., Woldeamanuel, Y. et al. Burden and antimicrobial resistance of S. aureus in dairy farms in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res 16, 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-2235-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-2235-8