Abstract

Background

Borrelia burgdorferi is the spirochete that causes Lyme Borreliosis (LB), which is a zoonotic tick-borne disease of humans and domestic animals. Hard ticks are obligate haematophagous ectoparasites that serve as vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi. Studies on the presence of Lyme borreliosis in Egyptian animals and associated ticks are scarce.

Methods

This study was conducted to detect B. burgdorferi in different tick vectors and animal hosts. Three hundred animals (dogs=100, cattle=100, and camels=100) were inspected for tick infestation. Blood samples from 160 tick-infested animals and their associated ticks (n=1025) were collected and examined for the infection with B. burgdorferi by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. The identified tick species were characterized molecularly by PCR and sequencing of the ITS2 region.

Results

The overall tick infestation rate among examined animals was 78.33% (235/300). The rate of infestation was significantly higher in camels (90%), followed by cattle (76%) and dogs (69%); (P = 0.001). Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus, and both Hyalomma dromedarii and Amblyomma variegatum, were morphologically identified from infested dogs, cattle, and camels; respectively. Molecular characterization of ticks using the ITS2 region confirmed the morphological identification, as well as displayed high similarities of R. sanguineus, H. dromedarii, and A. Variegatu with ticks identified in Egypt and various continents worldwide. Just one dog (1.67%) and its associated tick pool of R. sanguineus were positive for B. burgdorferi infection. The 16S rRNA gene sequence for B. burgdorferi in dog and R. sanguineus tick pool showed a 100% homology.

Conclusion

Analyzed data revealed a relatively low rate of B. burgdorferi infection, but a significantly high prevalence of tick infestation among domesticated animals in Egypt, which possesses a potential animal and public health risk. Additionally, molecular characterization of ticks using the ITS2 region was a reliable tool to discriminate species of ticks and confirmed the morphological identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lyme disease (LD) or the tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) is an emerging tick-borne multi-systemic zoonotic bacterial disease that has a worldwide distribution, caused by spirochetes of the Borrelia burgdorferi group and transmitted by ticks of the Ixodes ricinus complex [1]. The bacterium is horizontally transmitted between ticks and within reservoir hosts of wild animals, mostly small mammals, and humans which are considered an incidental host [2]. Clinical signs differ according to the species of B. burgdorferi complex prevailing in the area, but most human patients show erythema migrans accompanied by flu-like symptoms [2, 3]. Companion animals, particularly dogs, act as sentinels for Lyme disease [4]. Only 5–10% of infected dogs show clinical signs. Therefore, there is a significant underestimation of the Lyme disease prevalence in dogs, which represents a risk for disease spreading [5]. A previous survey on domestic animals detected borrelial DNA only in the adult ticks, mostly infesting sheep and cattle [6].

Ticks (subclass: Acari; order: Parasitiformes; suborder: Ixodida) are obligate haematophagous ectoparasites of wild and domestic animals and humans. Ticks are considered the most important vectors of disease-causing pathogens within the phylum Arthropoda, being comparable only to mosquitoes (family Culicidae) [7, 8]. As the incidence of tick-borne diseases propagates and expands geographically, it is becoming increasingly significant to distinguish tick species, to enhance tick and tick-borne disease control [9]. The brown tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus of dogs [10], the blue tick Rhipicephalus Boophilus of cattle [11], Hyalomma dromedarii of camels [12], and the tropical bont tick (TBT) Amblyomma variegatum of ruminants [13, 14], are of significant veterinary and medical importance due to their vector competence for several pathogens [15].

Despite the existence of various hard tick species in Egypt, limited data on the borrelial infection of these ticks is available. Here, we studied the infection of the hard ticks in Egypt with B. burgdorferi. Additionally, we investigated the prevalence and phylogeny of Borrelia in the tick-infested dogs, cattle, and camels during the year 2017.

Results

Prevalence of tick infestation in the studied animals

Rhipicephalus sanguineus was detected in 69% of sampled dogs, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus was detected in 76% of sampled cattle, and both Hyalomma dromedarii and Amblyomma variegatum were detected in 90% of examined camels. The relation between animal species and the tick infestation rate was significant, χ2 (2, N = 300) = 13.47, P = 0.001. Camels were more likely than dogs and cattle to be infested with ticks (Table 1). Camels showed a significantly higher infestation rate with Hyalomma dromedarii (93.33%) compared to Amblyomma variegatum (6.67%), χ2 (1, N = 90) = 135.2, P < 0.0001.

Species identification and phylogenetic analysis of ticks

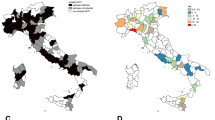

Ninety percent of examined camels from Cairo (Bassatin abattoir) and Matrouh governorates were infested with two species; H. dromedarii (93.3%) and A. variegatum (6.6%). Moreover, 76% of examined cattle found in Giza and Elbehira governorates, were infested with R. (Boophilus) annulatus. Additionally, 69% of dogs (stray dogs and other breeds) found in Cairo and Giza governorates infested with R. sanguineus (Table 1, Fig. 1).

R. sanguineus male (a&b), dorsal view (a) showed eyes are slightly convex (e), Basis capital has lateral sharp angles (bc), pale conscutum(co), distinctly lateral grooves (Lg), deep distinct posterior grooves (pg); ventral view (b) showed large accessory adenal plate (ac), narrow adenal plate (ad), caudal appendage (cd).R.(Boophilus) annulatus male (c&d), dorsal view (c) showed distinctly cornua (c), accessory adanal plates (ac), adanal plates (ad),; ventral view (d) showed accessory adanal plates (ac), adanal plates (ad), genital aperture (ga). H. dromedarii male(e&f), dorsal view (e) showed conscutum is dark colour (co), eyes(e), rings of leg segments are pale(rl), cervical fields are depressed (ce), central festoons are pale (fe), subanal plates(sa); ventral view (f) showed, accessory adanal plates (ac), round end of adanal plates (ad), subanal plates is outside the alignment of adanal plates (sa), genital aperture (ga), anus aperture (ap). A. Variegatum male (g&h), dorsal view (g) showed posterior median stripe is narrow (pm), convex eyes are distinct(ce) pale ring of leg segments are distinct (rl), orange to pink enamel colour of conscutum (co), festoons colour are non-enamelled (fe); ventral view(h) showed genital aperture (ga), anus aperture(ap)

Phylogenetic analysis, based on the ITS2 region sequences of ticks, revealed relatedness of Egyptian ticks R. sanguineus, H. dromedarii, and A. Variegatu with other tick isolated from different continent all over the world, as shown in (Fig. 2).

Detection and phylogenetic analysis of B. burgdorferi

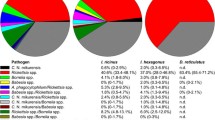

Borrelia burgdorferi was detected in a Rhipicephalus sanguineus tick collected from a dog that was also infected (Tables 1 and 2). Based on the 16S rRNA gene of B. burgdorferi collected from dog blood and ticks, a hundred percent of identity were reported between B. burgdorferi isolated from the blood of dogs (MH685928) and brown dog ticks (MH685927) in Egypt, as well as B. burgdorferi isolated from Ixodes pacificus in the USA (KY563172) (Fig. 3).

Genospecies identification of ticks

Discussion

Studies on Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) in Egypt are limited, especially in animals and tick vectors. Besides, the recent large-scale movements of humans and animals, as well as the increasing geographical distribution of several tick species, contributed to the growing global threat of tick-borne disease (TBD) [8, 15]. Therefore, in the current study we moleculary identified the hard tick population infesting the examined animals, as well as, investigated the prevalence and phylogeny of B. burgdorferi in dogs, cattle, camels, and associated ticks.

In this study, the overall rate of tick infestation in dogs, cattle, and camels, was 78.33% (160/300). The same infestation rate, 78.3% (369/471) in livestock animals, was reported by [4] in Pakistan. Morphological identification of collected ticks indicated that dogs (69%) were infested with Rhipicephalus sanguineus, cattle (76%) were infested with Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) annulatus, while camels (90%) were infested with either Hyalomma dromedarii (93.33%) or Amblyomma variegatum (6.67%). Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick) is the most widespread tick in the world, infesting dogs living in both urban and rural areas [15]. The prevalence of R. sanguineus agreed with [16] who reported a 67.5% R. sanguineus infestation rate in dogs in Egypt. In southeast Brazil, [17] recorded that 89.7% of dogs were infested with R. sanguineus, while in the Philippines, [18] recorded 2.60% prevalence of R. sanguineus infestation in dogs. In camels, Hyalomma dromedarii was the most abundant tick species, which agrees with the previous study conducted by [19].

Although the morphological identities of identified ticks were similar to the taxonomic key of Ixodidae ticks set by [20], further molecular identification of ticks was carried out through the examination of the ITS2 region. The choice of the ITS2 region was based on the previous studies [21, 22],which indicated that this DNA marker is reliable in discriminating species of ticks. The sequence of the ITS2 region of our isolates showed varying degrees of similarities with local and international hard tick species. The dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (MH685437) showed the highest similarity (99.7%) with R. sanguineus obtained from Alexandria (KY945496) and the neighboring countries; as Israel (KF958410, KF958409, KF958404, KF958398). However, it showed a 19.3% homology with R. sanguineus (MH616088) collected from Brazil. This difference in similarity agreed with [23,24,25] who classified R. sanguineus group into tropical and temperate strains. Rhipicephalus annulatus (MH685437) of cattle, showed a 100% homology with Egyptian strains (MF946470, KY945495) collected from Al Buhayra Governorate, as well as a Romanian strain (KC503267). However, the Rhipicephalus annulatus (MH685437) showed 81.6% homology with R. annulatus (JQ412126) collected from Fayoum governorate in Egypt. Those intra-species and inter-species similarities could be due to the agreements in the area of sample collection from northern Egypt as well as the same infested cattle population. Genetic identity of the Egyptian Hyalomma dromederii (MH685931) collected in this study from camels (Camelus dromedaries), proved a high sequence homology of 100% similarity with previous H. dromederii isolates from Matrouh in Egypt, with accession no. MF946469, KY945494. On the other hand, the phylogenetic analysis of A. variegatum in this study (MH685932) was a pioneer one, as no earlier reports on similar molecular taxonomy or evolutionary analyses on A. variegatum was recorded in Egypt. Amblyomma variegatum in this study (MH685932) showed a 97.7% homogeneity with A. variegatum collected from cattle in France (MH910967) [26] and 99.9% with one collected from wild herbivores in Kenya (KM819713).

The detection of borrelial DNA in infested animals and associated ticks revealed that one dog (1.67%) and its associated pool of adult Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks (1.67%) were infected with B. burgdorferi. The low tick infection rate with B. burgdorferi reported in our study disagrees with that recorded in Fayoum and Beni-Suif in Egypt, by [27] who reported 7/12 (58.33%) infected pools of R. sanguineus. This difference could be assigned to different geographical locations; as Cairo and Giza are more urbanized than Fayoum and Beni-Suif which are mostly rural governorates. The prevalence of B. burgdorferi in the examined dogs in Italy was 1.47%. In the USA, infection rates with B. burgdorferi recorded 1.2, 4.0, and 6.7% in dogs from three different regions [28, 29]. The most recent investigations about the prevalence of B. burgdorferi epidemic in the European canine population exposed different rates, as the highest incidence observed in Poland 40.2% [30, 31] and the lowest was in Portugal 0.2–0.5% [32] In a previous study [6] in Iran, researchers could detect borrelial DNA only in the adult ticks. They attributed the lack of Borrelia infection in nymphs to limited nymph samples as they were unable to catch the immature specimen.

In our study, the identity of B. burgdorferi that was isolated from the dog’s blood (MH685928) and the associated brown tick pool of R. sanguineus (MH685927) in Egypt, as well as B. burgdorferi isolated from Ixodes pacificus in the USA (KY563172), were 100% in similarity. From the veterinary and public health points of view, scientists should be aware that ticks are active in broad climatic conditions, even greater than those expected. The current level of knowledge about LB risk and the risk related to tick bites is quite limited and underestimated.

Conclusion

In Egypt, the domestic animal population is markedly infested with the hard ticks, which threatens the animal and public health with potential tick-borne pathogens. Our data revealed that the camel tick H. dromedarii is the most prevalent tick in Egypt. The molecular taxonomy of tick species is going to be a standard approach for confirming the morphological identification of ticks. Molecular detection of borrelial DNA showed a relatively low rate of B. burgdorferi infection in dogs and associated ticks. However, dogs act as a potential sentinel carrier of Lyme disease. Since B. burgdorferi is of zoonotic importance, routine monitoring of domestic animals, adequate control measures, and increased awareness of the possible Lyme Borreliosis infections are required for consideration of this pathogen in the differential diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Methods

Sampling

Ticks collection

A three hundred Dogs (stray and pet dogs), cattle (native breed), and camels (Camelus dromedaries), 100 animals each, from Cairo, Giza, Al-Buhayrah, and Matrouh governorates, were inspected for tick infestation, for 1 year (2017). Adult hard tick samples were collected and isolated from those naturally infested animals, as indicated in the (Table 3) and (Fig. 4). Ticks were pulled off manually from the animals by hands and with blunt point forceps, then placed in a sterile loosely capped plastic vials and transported to the laboratory in a dry icebox. In the laboratory, the ticks were identified and stored at − 20 °C.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were collected from hard tick-infested animals, including dogs (n = 60), cattle (n = 50), and camels (n = 50) from some Egyptian governorates, which are shown in (Table 3) and (Fig. 4). The blood samples were collected in tubes coated with EDTA from the cephalic vein in dogs, and the Jugular vein in cattle and camels. All blood samples were transported to the laboratory in an icebox and stored at − 20 °C until use.

Tick identification

Morphological identification of ticks

Tick samples were kept at room temperature and then washed twice with sterile normal saline to remove excess particulate contamination from animal skin, rinsed once with 70% ethanol. They were mounted on slides and examined using a stereoscope microscope (BOECO, Germany). Adult ticks were identified into genera, species, and subspecies by using appropriate identification keys of morphological shapes [33]. About 20 ticks were taken from each dog and about 30–35 ticks were taken from each cattle or camel as a target number of ticks from each animal, we did not collect all the ticks infesting on each animal, which is considered a limitation of the study. The identified ticks were transferred to sterile vials and stored at − 20 °C until processing.

Molecular identification of ticks

Ticks’ DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from each morphologically identified tick sample, after being crushed in a mortar with liquid nitrogen into small pieces, by using a DNA extraction kit (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, QIAGEN; Germany) according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Tick identification by PCR

Genomic DNA extracted from the ticks’ tissues was amplified using primers designed for ITS2 amplification [34]; forward 5′-YTGCGARACTTGGTGTGAAT-3′ and reverse 5′- TATGCTTAARTTYAGSGGGT-3′ (Bio Basic Inc., Canada).

PCR conditions was done according to Muruthi et al., 2016 [35]. Amplification reactions were visualized on a 1% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma), while a 1 kb DNA ladder (Invitrogen™) was used as a marker. The gel was visualized under UV light with a transilluminator.

Sequencing of ticks’ PCR products and phylogenetic analysis

PCR products of the identified ticks were purified from the reactions using the Qiaquick purification kit for tissues (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was conducted using Big Dye Terminator V3.1 sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) with forward primer ITS2 ribosomal DNA. Phylogenetic analysis was based on the ITS2 region sequences of ticks. The trees were constructed and analyzed by neighbor-joining.

Molecular detection of Borrelia burgdorferi 16S rRNA gene in blood and tick samples

DNA extraction from blood and ticks

DNA was extracted from blood samples using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), and from tick samples using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit for tissue (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA extract was stored at − 20 °C until being used in the PCR assay.

Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi by PCR

PCR was performed using BbF and BbR PCR primers of the 16S rRNA gene, according to [36], in a reaction volume of 50 μl, containing 0.625 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fischer), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTP), 12.5 pmol of species-specific primers for B. burgdorferi BbF 5′-GGGATGTAGCAATACATTC-3′ Position (72–90) and BbR 5′- ATATAGTTTCCAACATAGG-3′ Position (631–649), 5 μl extracted DNA from blood samples and ticks.

PCR with species-specific primers consisted of an initial denaturation (1 min at 94 °C), followed by 35 cycles using the temperature profile 95 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1.5 min. Negative control samples (no template DNA) which were subjected to identical procedures, were used to monitor contamination, the expected molecular weight is 577 bp. 10 μL of the amplification products were analyzed on ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gel in TAE buffer (0.04 M tris-acetate, 0.002 M EDTA, pH 8) after horizontal electrophoresis at 80 V for 45 min [37, 38].

Sequencing of B. burgdorferi PCR product and phylogenetic analysis

PCR products of positive B. burgdorferi samples (blood and ticks) were purified from the reactions using the Qiaquick purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was conducted using Big Dye Terminator V3.1 sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) with forward primer 16S rRNA. The obtained nucleotide sequence was compared with those available in public domains using NCBI, BLAST server. Sequences were downloaded and imported into BioEdit version 7.0.1.4 for multiple alignments using the Clustal W program of the BioEdit. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with MEGA version 7 using the neighbor-joining method. The bootstrap consensus tree was inferred from 950 replicates (Fig. 3).

The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences recovered from Borrelia burgdorferi strains isolated from different sources, including Dog (MH685928) and Tick (MH685927) and aligned with the other related 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from GenBank NCBI-BLAST.

Statistics and spatial data

Analysis of data was performed with PASW Statistics, Version 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data collected were analyzed using both the descriptive statistic (frequencies) and the Chi-square (χ2) test for independence to examine the relation between animal species and tick infestation rates. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The map was created with ArcMap version 10.1 software.

The study was performed according to the guidelines of the ethical committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee), Faculty of veterinary medicine, Cairo University, Vet CU. IACUC (VetCU1022019070).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are available in the [GENE BANK] repository, accsession numbers: [MH685928, MH685927, MH685437, MH685931, MH685932].

Abbreviations

- LB:

-

Lyme Borreliosis

- Bb:

-

Borrelia burgdorferi

- TBD:

-

Tick-borne disease

References

Pukhovskaya NM, Morozova OV, Vysochina NP, Belozerova NB, Ivanov LI. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Borrelia miyamotoi in ixodid ticks in the Far East of Russia. Int J Parasitol. 2019;8:192–202.

Diuk-Wasser MA, Hoen AG, Cislo P, Brinkerhoff R, Hamer SA, Rowland M, Cortinas R, Vourc'h G, Melton F, Hickling GJ, Tsao JI. Human risk of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, in eastern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(2):320–7.

Qiu WG, Bruno JF, McCaig WD, Xu Y, Livey I, Schriefer ME, Luft BJ. Wide distribution of a high-virulence Borrelia burgdorferi clone in Europe and North America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):1097.

Smith FD, Ballantyne R, Morgan ER, Wall R. Estimating Lyme disease risk using pet dogs as sentinels. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;35(2):163–7.

Little SE, Heise SR, Blagburn BL, Callister SM, Mead PS. Lyme borreliosis in dogs and humans in the USA. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(4):213–8.

Naddaf SR, Mahmoudi A, Ghasemi A, Rohani M, Mohammadi A, Ziapour SP, et al. Infection of hard ticks in the Caspian Sea littoral of Iran with Lyme borreliosis and relapsing fever borreliae. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11(6):101500.

Hoogstraal H. Argasid and nuttalliellid ticks as parasites and vectors. Adv Parasitol. 1985;24:135–238 Academic Press.

de la Fuente J, Estrada-Pena A, Venzal JM, Kocan KM, Sonenshine DE. Overview: ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Front Biosci. 2008;13(13):6938–46.

Ganjali M, Dabirzadeh M, Sargolzaie M. Species diversity and distribution of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Zabol County, eastern Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2014;8(2):219.

Dantas-Torres F, Melo MF, Figueredo LA, Brandão-Filho SP. Ectoparasite infestation on rural dogs in the municipality of São Vicente Férrer, Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2009;18(3):75–7.

Onofre SB, Miniuk CM, de Barros NM, Azevedo JL. Pathogenicity of four strains of entomopathogenic fungi against the bovine tick Boophilus microplus. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62(9):1478–80.

Sivakumar G, Swami SK, Nagarajan G, Mehta SC, Tuteja FC, Ashraf M, Patil NV. Molecular characterization of Hyalomma dromedarii from North Western region of India based on the gene sequences encoding Calreticulin and internally transcribed spacer region 2. Gene Reports. 2018;10:141–8.

Barré N, Uilenberg G. Propagation de parasites transportés avec leurs hôtes: cas exemplaires de deux espèces de tiques du bétail. 2010.

Rahajarison P, Arimanana AH, Raliniaina M, Stachurski F. Survival and moulting of Amblyomma variegatum nymphs under cold conditions of the Malagasy highlands. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;28:666–75.

Dantas-Torres F, Chomel BB, Otranto D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a one health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28(10):437–46.

Abuowarda MM, Haleem MA, Elsayed M, Farag H, Magdy S. Bio-pesticide control of the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) in Egypt by using two Entomopathogenic Fungi (Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae). Int J Vet Sci. 2020;9(2):175–81 www.ijvets.com.

Heukelbach J, Frank R, Ariza L, de Sousa LÍ, AD e S, Borges AC, Limongi JE, de Alencar CH, Klimpel S. High prevalence of intestinal infections and ectoparasites in dogs, Minas Gerais state (Southeast Brazil). Parasitol Res. 2012;111(5):1913–21.

Bartolome-Cruz K. Prevalence and intensity of infestation of the brown dog tick, rhipicephalus sanguineus (latreille) (arachnida: Acari: ixodidae) in three veterinary facilities. Philipp J Vet Med. 2018;55(2):107–14.

Abdullah HH, El-Shanawany EE, Abdel-Shafy S, Abou-Zeina HA, Abdel-Rahman EH. Molecular and immunological characterization of Hyalomma dromedarii and Hyalomma excavatum (Acari: Ixodidae) vectors of Q fever in camels. Vet World. 2018;11(8):1109.

Walker JB, Keirans JE, Horak IG. The genus Rhipicephalus (Acari, Ixodidae): a guide to the brown ticks of the world. England: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Song S, Shao R, Atwell R, Barker S, Vankan D. Phylogenetic and phylogeographic relationships in Ixodes holocyclus and Ixodes cornuatus (Acari: Ixodidae) inferred from COX1 and ITS2 sequences. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41(8):871–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.03.008.

Lv J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Feng C, Yuan X, Jia G, Deng J, Wang C, Wang Q, Mei L. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):93.

Dantas-Torres F, Latrofa MS, Annoscia G, Giannelli A, Parisi A, Otranto D. Morphological and genetic diversity of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato from the New and Old Worlds. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):213.

Moraes-Filho J, Marcili A, Nieri-Bastos FA, Richtzenhain LJ, Labruna MB. Genetic analysis of ticks belonging to the Rhipicephalus sanguineus group in Latin America. Acta Trop. 2011;117(1):51–5.

Sanches GS, Évora PM, Mangold AJ, Jittapalapong S, Rodriguez-Mallon A, Guzmán PE, Bechara GH, Camargo-Mathias MI. Molecular, biological, and morphometric comparisons between different geographical populations of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet Parasitol. 2016;215:78–87.

Cicculli V, de Lamballerie X, Charrel R, Falchi A. First molecular detection of rickettsia africae in a tropical bont tick, Amblyomma variegatum, collected in Corsica, France. Exp Appl Acarol. 2019;77(2):207–14.

Elhelw RA, El-Enbaawy MI, Samir A. Lyme borreliosis: a neglected zoonosis in Egypt. Acta Trop. 2014;140:188–92.

Bowman D, Little SE, Lorentzen L, Shields J, Sullivan MP, Carlin EP. Prevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in dogs in the United States: results of a national clinic-based serologic survey. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160(1–2):138–48.

Carrade D, Foley J, Sullivan M, Foley CW, Sykes JE. Spatial distribution of seroprevalence for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs in Washington, Oregon, and California. Vet Clin Pathol. 2011;40(3):293–302.

Skotarczak B, Wodecka B, Rymaszewska A, Sawczuk M, Maciejewska A, Adamska M, et al. prevalence of DNA and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in dogs suspected of borreliosis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2005;12:199–205.

Zygner W, Gorski P, Wedrychowicz H. Detection of the DNA of Borrelia afzelii, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia canis in blood samples from dogs in Warsaw. Veterinary Record. 2009;64(15):465–7.

Cardoso L, Mendão C, Madeira de Carvalho L. Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis, Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma spp. Leishmania infantum in apparently healthy and CVBD-suspect dogs in Portugal: a national serological study. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:62.

Walker AR. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa: a guide to identification of species. Edinburgh: Bioscience Reports; 2013.

Abdigoudarzi M, Noureddine R, Seitzer U, Ahmed J. rDNA-ITS2 identification of Hyalomma, Rhipicephalus, Dermacentor and Boophilus spp.(Acari: Ixodidae) collected from different geographical regions of Iran. Adv Stud Biol. 2011;3(5):221–38.

Muruthi CW, Lwande OW, Makumi JN, Runo S, Otiende M, Makori WA. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of ticks sampled from wildlife species in selected conservation sites of Kenya. J Vet Sci Technol. 2016;10:2157–7579.

Marconi RT, Garon CF. Identification of Lyme Disease Isolates by 16S rRNA Signature Nucleotide Analysis.

Zore A, Petrovec M, Prosenc K, Trilar T, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Avsic-Zupanc T. Infection of small mammals with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Slovenia as determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1999;111(22/23):997–9.

Santino I, Berlutti F, Pantanella F, Sessa R, Del Piano M. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato DNA by PCR in serum of patients with clinical symptoms of Lyme borreliosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;283(1):30–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.R, E.M and H.D: planed the study, carried out the experimental work, conducted the analysis of data and wrote the manuscript; A.M: performed the parasitological examinations and analysis, participated in writing;. I.E and H.S: participated in the experiments and manuscript writing. The manuscript had been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was according to the guidelines of the ethical committee of the faculty of veterinary medicine, Cairo University. (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee), Vet CU. IACUC (VetCU1022019070).

We had been given oral consent from the owners of the animals as we had just taken ticks and blood samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Elhelw, R., Elhariri, M., Hamza, D. et al. Evidence of the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi in dogs and associated ticks in Egypt. BMC Vet Res 17, 49 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02733-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02733-5