Abstract

Background

Fusarium infection with concurrent production of deoxynivalenol (DON) causes an increasing safety concern with feed worldwide. This study was conducted to determine the effects of varying levels of DON in diets on growth performance, serum biochemical profile, jejunal morphology, and the differential expression of nutrients transporter genes in growing pigs.

Results

A total of twenty-four 60-day-old healthy growing pigs (initial body weight = 16.3 ± 1.5 kg SE) were individually housed and randomly assigned to receive one of four diets containing 0, 3, 6 or 12 mg DON/kg feed for 21 days. Differences were observed between control and the 12 mg/kg DON treatment group with regards to average daily gain (ADG), although the value for average daily feed intake (ADFI) in the 3 mg/kg DON treatment group was slightly higher than that in control (P<0.01). The relative liver weight in the 12 mg/kg DON treatment group was significantly greater than that in the control (P<0.01), but there were no significant differences in other organs. With regard to serum biochemistry, the values of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate amino transferase (AST) in the 3 treatment groups were higher than those in the control, and the serum concentrations of L-valine, glycine, L-serine, and L-glutamine were significantly reduced in the 3 treatment groups, especially in the 12 mg/kg DON group (P<0.01). Serum total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) were markedly decreased after exposure to DON contaminated feeds (P<0.01). The villi height was markedly decreased and the lymphocyte cell numbers markedly increased in the 3 DON contaminated feeds (P<0.01). The mRNA expression levels of excitatory amino acid transporter-3 (EAAC-3), sodium-glucose transporter-1 (SGLT-1), dipeptide transporter-1 (PepT-1), cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1) and y+L-type amino acid transporter-1 (LAT-1) in control were slightly or markedly higher than those in the 3 DON treatment groups.

Conclusions

These results showed that feeds containing DON cause a wide range of effects in a dose-dependent manner. Such effects includes weight loss, live injury and oxidation stress, and malabsorption of nutrients as a result of selective regulation of nutrient transporter genes such as EAAC-3, SGLT-1, PepT-1, CAT-1 and LAT-1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The trichothecene deoxynivalenol (DON) is a secondary metabolite mainly produced by the plant pathogens Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium culmorum, to which human and livestock can be exposed via food and feed [1]. Fusarium infection of wheat, barley and corn with concurrent production of DON and other trichothecene mycotoxins is an increasing food safety concern worldwide [1, 2]. Many published papers show the toxic effects of DON on animals mainly impairing immune system, health status of the gastrointestinal tract and the brain [1, 3–6]. Some reports suggested that ingestion of these DON may induce feed refusal, organ damage, increased disease incidence, and malabsorption of nutrients [1, 3, 7–13]. Some papers showed in the in vitro studies that DON interfere with differentiation of different intestinal cell line models [10–14]. In vivo, much attention has been given to the determination of glucose absorption after DON exposure but only limited studies have assessed expression of nutrient transporter genes when feeding functional nutrients to alleviate poisoning triggered by a single dose of dietary DON exposure [9, 15–22]. DON is effectively absorbed in the upper gastro-intestinal tract (GIT), i.e. stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum [23]. It is, therefore, hypothesized that DON will impair absorption of nutrients including amino acid, di/tripeptides, and glucose by reducing expression of genes for transporters of these nutrients especially in the upper GIT. Duration and amount of DON exposure seem to be crucial factors for toxic effect on nutrient digestibility and absorbability as previously shown in swine and cell line models [23, 24]. However, there has been no systematic investigation to date of the DON-triggered effects in growth performance, serum parameters, jejunal morphology, and in the expression of nutrient transporter genes.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the effects of various levels (0 to 12 mg/kg) of dietary DON challenge on growth performance, serum biochemical and amino acid profile, jejunal morphology, and the differential expression of genes for nutrient transporters in growing pigs.

Results

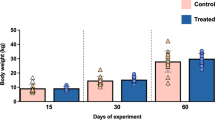

Growth performance

The cumulative performance results of growing pigs are showed Table 1. There was no significant difference between control, 3 mg/kg DON group, and 6 mg/kg DON groups with regard to average daily gain (ADG), but this value in 12 mg/kg DON groups was significantly lower than those in the other groups (P < 0.05). The average daily feed intake (ADFI) was no significant difference between control and 3 mg/kg DON group, but this value in 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.05). The 6 mg/kg DON group showed the lowest feed/gain ratio (F/G).

Relative organ weights

Table 2 shows the effects of dietary DON-contaminated diet on relative organ weights in 60-to 88-day-old pigs. There were no significant differences among the four groups with regard to the spleen, kidney and heart (P>0.05). However, the relative liver weights in the pigs fed the diets with 3 mg/kg DON and 12 mg/kg DON were higher than control. No differences were seen among the DON contaminated diets.

Serum biochemical parameters and amino acid concentrations

Table 3 shows effects of three dose DON-contaminated diet on serum biochemical parameters of pigs from age 60 to 88 days. There was no difference in the concentrations of albumin (ALB), creatinine (CRE) and serum fasting blood glucose (GLU) between control group and the DON treatment groups (P>0.05). The blood urea nitrogen (BUN) values were similar in the 3 mg/kg DON and 6 mg/kg DON groups, but values in the 6 mg/kg DON and 12 mg/kg DON groups were significantly higher than control (P < 0.05). The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly higher than in control, 3 mg/kg DON and 6 mg/kg DON groups (P < 0.01). The alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activities in 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly higher than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The aspartate amino transferase (AST) activities in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly higher than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01).

Table 4 shows effects of 3 dose DON-contaminated diet on serum amino acid concentrations of pigs from age 60 to 88 days. The L-arginine concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control, 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The L-histidine concentration in 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control (P < 0.05). The L-lysine concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control, 3 mg/kg DON group and 6 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The L-threonine concentration in 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control (P < 0.01). The concentrations of L-valine, glycine and L-serine in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The L-glutamate concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control, 3 mg/kg DON and 6 mg/kg DON groups (P < 0.01). The L-tyrosine of concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON groups (P < 0.05). The L-aspartate concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON groups (P < 0.05). The L-glutamine concentration in 6 mg/kg group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control (P < 0.01). The L-alanine concentration in 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON groups (P < 0.01).

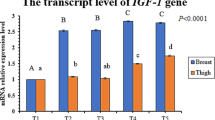

Serum hormonal components

Table 5 shows dietary effects on serum growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), haptoglobin (HP) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) concentrations. The serum activity of GH in 12 mg/kg DON group was significantly lower than 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.05). The serum activity of IGF1 in control group and 3 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than those 2 groups (P < 0.01). The serum activity of T-SOD in 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The HP in control group and 3 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The GSH-Px in 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group were significantly lower than control and 3 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01).

Jejunal morphology

No abnormal morphology was observed for the jejunal morphology in the control (Fig. 1). Table 6 shows the jejunal morphology changes of growing pigs fed with 3 dose DON-contaminated diet. The villus height of the jejunal in control and 3 mg/kg DON group were significantly higher than 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.05). The crypt depth of the jejunal was no significant differences among the 4 groups. The lymphocyte number of the jejunal in control was significantly lower than 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.05).

The Jejunal morphology (HE × 100) changes of in growing pigs fed with three different dose Deoxynivalenol (DON) contaminated diet. Pigs in the control group (Panel 1) and 6 mg/kg DON group (Panel 3) were fed a DON uncontaminated diet and a 6 mg/kg DON contaminated diet, respectively. Pigs in the 3 mg/kg DON (Panel 2) and 12 mg/kg DON group (Panel 4) were fed a 3 mg/kg DON contaminated diet and a 12 mg/kg DON contaminated diet, respectively. The scale bars in Fig. 1 represent 100 μm

mRNA expression of nutrients transporter genes

Eight critical intestinal amino acid transporters (excitatory amino acid transporter-3 (EAAT-3), b0,+amino acid transporter (B0,+AT), sodium-glucose transporter-1 (SGLT-1), glucose transporter-2 (GLUT-2), dipeptide transporter-1 (PepT-1), Na+-dependent neutral amino acid exchanger-2 (ASCT-2), cationic amino acid transporter-1 (CAT-1) and y+L-type amino acid transporter-1 (LAT-1)) mRNA expressions were tested at the end of feeding, and the results were shown in the Table 7. The mRNA expressions level of the EAAT3 in control was significantly higher than in the 3 DON treatment groups (P < 0.01). The mRNA expression levels of the B0,+AT, GLUT-2 and ASCT-2 were no significantly different among the 4 groups. The mRNA expressions level of the SGLT-1 in control and 3 mg/kg DON group were significantly higher than 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The mRNA expressions level of the PepT-1 in 3 mg/kg DON group was significantly higher than 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01). The mRNA expressions level of the CAT-1 and LAT-1 in control and 3 mg/kg DON group were significantly higher than 6 mg/kg DON group and 12 mg/kg DON group (P < 0.01).

Discussion

DON is a common contaminant of cereal crops like wheat, barley, corn and oats and of high importance in food industry, and increasingly a food safety issue problem worldwide. Understanding of variable DON toxicology also requires the systematic combination of growth performance, serum biochemical profile, jejunal morphology, especially for the expression different nutrient transporter genes when pigs are exposed to different doses of DON and coherent responses on animal or human health. Considering that the gastrointestinal tract and the immune system of pigs are not vastly different that of humans, the pig can be regarded as a good model that can be applied to humans [25]. In the present study when pigs were fed 3 dose DON-containing diets, especially significantly in 12 mg/kg DON group compared with other 3 groups (P < 0.01). Consistent with previous studies examining the impact of dietary DON, feed intake was significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1) [18, 26–34]. This finding supports the hypothesis that the adverse effects of DON contaminated diets on growth performance of growing pigs is primarily caused by depressing the voluntary feed intake [34–40].

In the present study, the relative liver weight in the 12 mg/kg DON treatment group was significantly greater than that in the control (P<0.01), but there were no significant differences in other organs (Table 2). The report demonstrated that there were no changes in organ weights with the use of DON concentrations ranging from 750 to 3000 μg/kg [39]. It is not consistent with Chaytor and co-workers, which analyses the effect of the combination of DON and aflatoxins on the weights of internal organs, and found no changes in the weights of the liver, kidney or spleen [7]. The organ weights related to live weight seem to be more appropriate for interpreting the DON effects. A possible explanation for discrepancies between this latter study and our present study could be that the effect of DON on relative organ weights are dependent on the age of pigs, duration of exposure of pigs to DON and the dose of DON [35].

The serum levels of ALB, BUN, GLU, CRE, ALP, ALT and AST were tested as a reflection of the metabolism and visceral organ status of pigs (Table 3). There was no difference in ALB levels, CRE level and GLU level between control and 3 DON treatment groups (P>0.05). It is consistent with previous result showing that dietary exposure to DON has no significant effect on plasma protein concentrations (total protein, albumin and fibrinogen) [41], however, and it is not consistent with previous results showing that the decreased albumin levels have been found in pigs fed a DON-contaminated diet [36]. The increase in ALP in toxin control reflected the abnormal excretion of liver metabolites due to DON-induced systemic toxicity, as described in a previous study [7]. Serum AST and ALT levels have been reported to be sensitive indicators of liver injury, since an increase in these values reflects leakage from injured hepatocytes [42]. The increase in AST and ALT in the 3 DON treatment groups compared with control indicated that this injured mechanism is triggered after DON diet intake, and the result was consistent with relative live weights (Table 2).

Amino acids play important roles as metabolic intermediates in nutrition, immune response, and growth performance [43]. In the present work, we observed that concentrations of L-valine, glycine, L-serine, and L-glutamine in serum were significant decreased by the exposure to DON in feedstuffs, especially significant in 12 mg/kg DON group (P<0.01). It is not consistent with our previously reports showing that the dietary supplementation with functional nutrients in a single dose DON exposure [17–19]. A possible reason was the degradation of dietary valine, glycine, glutamine, and serine by the small intestine is increased by 3 dose DON-contaminated food, resulting in their deficiencies in the animals. Increasing evidence shows that these amino acids are very important for tissue protein synthesis and metabolic regulation [43–45].

Antioxidant enzymes comprise a major defense system for preventing organ injury due to excessive quantities of reactive oxygen species that attack proteins, lipids, and DNA, such as T-SOD, HP and GSH-Px [46, 47]. Most of the studies have demonstrated that some mycotoxins can contribute to oxidative stress in cells [48–50]. In the present study, we found that the activity of T-SOD, GSH-Px in the pig serum was markedly decreased after exposure to DON contaminated diets, indicating that DON resulted in oxidative stress in the whole body (Table 5). For the changes of GH and IGF1 in our study, only IGF1 levels were markedly decreased after exposure to DON contaminated diets (Table 5), which is consistent with previously reports [51, 52]. A possible mechanism for the DON-induced IGF-1 suppression involves the induction of IL-6 and other proinflammatory cytokines, which down-regulates the sensitivity of the GH receptor via suppressor of cytokines (SOCS)-and signal transducers and activator of transcription (STAT)-related mechanisms [53, 54].

The main morphological and histological effects observed included villi flattening and shortening, apical necrosis hyperemia and a reduction in the number of goblet cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 1 and Table 6). The villi height reduction indicate that DON resulted in malabsorption and impairment in the jejunum. Similar changes were observed during in vivo and ex vivo exposure of the intestine to DON [55, 56]. The toxic effects of DON are mediated via the inhibition of protein synthesis, thus primarily affecting rapidly dividing cells such epithelial and immune cells [1, 2]. Thus, the observed villi flattening and shortening in the jejunum is probably due to the impairment of cell proliferation as as shown in the Figs. 1. A hyperplasia of intestinal goblet cells has been observed in piglets and broiler chicks receiving feed contaminated with 30 and 300 mg FB1/kg feed, respectively [57, 58]. In the present study, a slightly decrease in the number of goblet cells and a increase lymphocyte cells were observed (Table 6). Intestinal mucus protects the epithelium against adhesion and invasion by pathogens, therefore, a increment in the number of lymphocyte cells can affect the intestinal barrier function [18, 19, 59, 60].

The absorption of amino acids mainly depends on their transporters on the membrane of the enterocyte [17, 61]. The mRNA expressions level of the B0,+AT, GLUT-2 and ASCT-2 were no significant differences among the 4 groups, intestinal protein levels for these transporters need to be quantified using western blot techniques [62]. The EAAC-3 is a sodium dependent glutamate transporter that can transport neutral amino acids, especially glutamate and cysteine, into intestinal vesicles [63]. The SGLT-1, which appears gradually on the apical membrane during the differentiation of enterocytes, but in mature enterocytes, the SGLT-1 is the main sugar transport system [64, 65]. In the piglet small intestine, PepT-1 mainly transports dipeptides and tripeptides from the digestion of dietary proteins [66]. In addition, CAT-1 transports cationic amino acids in the kidney and the small intestine, whereas LAT-1 transporter is a mediator of cationic amino acid efflux from epithelial cells [67]. In the present study, the mRNA expressions level of EAAC-3, SGLT-1, PepT-1, CAT-1 and LAT-1 in control were slightly or significantly higher than in the in the 3 DON-containing treatment groups. The SGLT-1 data, unlike that of GLUT-2, in the present study was consistent with that of study of Maresca et al. [11]. The EAAC and CAT-1 data were not consistent with our previous data obtained with a single dose of DON exposure [18]. Combined with the results of the present study and previously published data, it is clear that DON can decrease absorption of glucose, amino acid and peptide by inhibiting the mRNA expression of the relevant transporters [17–19]. However, the mRNA expression of amino acid transporters in the amino acid absorption ratio did not strictly correspond to the changes in amino acid intake [18]. This relationship between amino acid expression and amino acid intake in DON-contaminated pigs will require further investigation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, feeding DON-contaminated diets to growing pigs significantly reduced feed intake resulting in decreased growth performance. This further altered serum biochemical and amino acid profiles, jejunal morphology, and the mRNA expression of nutrients transporter genes. Therefore, dietary DON can selectively decreased the mRNA expression of nutrient transporter genes in growing pigs.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving animal subjects were approved by the animal welfare committee of the Institute of Subtropical Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Changsha, Hunan Province, China).

Preparation of mouldy corn

Fusarium graminearum isolate R6576 was obtained from the College of Plant Science & Technology of Huazhong Agricultural University (Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). Preparation, cultivation and collection of fungus from mouldy corn was performed as described previously [17–19]. In brief, water was added to a non-contaminated basal diet until it reached 20 % moisture. The wet feed was then cultured under ambient conditions (temperature 23–28 °C, humidity 68–85 %) until mildew was clearly observed. Finally, the mold contaminated diet was naturally air-dried, mixed, and sampled for detection of mycotoxins. The contents of mycotoxins in mould-contaminated feed were detected by liquid chromatography as described previously (Beijing Taileqi, Beijing, China) (Table 8) [17–19].

Pigs management and sample collection

A total of twenty-four 60 day-old healthy growing pigs (Landrace × Large × Yorkshire) (Zhenghong Co., Ltd., Hunan Province, China) with a mean body weight of 16.3 ± 1.5 kg were randomly assigned to 4 dietary treatments: (1) a DON-free diet (control); (2) a diet with 3 mg DON/kg; (3) a diet with 6 mg DON/kg diet; and (4) a diet with 12 mg DON/kg of diet. There were 6 pigs per group (three male; three female). All diets were formulated to meet the National Research Council (1998) recommended nutrient requirements for growing pigs. The ingredient and nutrient composition of the diets is as reported by our previously report [18]. Before the pigs were challenged with DON, pigs were allowed to acclimatize to the housing conditions with access to a commercial diet with 1.64 % Alanine as isonitrogenous control for 7 days. Pigs had free access to drinking water and their respective diets throughout the experimental period. After 21 days of dietary exposure to DON, and immediately after electrical stunning, the pigs were killed for analysis. Body weight and feed consumption were recorded.

After 21 days of dietary exposure to DON, 5 mL of blood was collected aseptically in tubes from a jugular vein 2 h after feeding, centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain serum samples, and stored at –80 °C for further analysis. The liver, spleen, kidney and heart were removed and weighed. The weights were recorded both as the organ weight and the weight as a percent of the total body weight. The small intestine was rinsed thoroughly with ice-cold physiological saline solution (PBS) and the jejunum and ileum were dissected.

Analysis of serum biochemical parameters and amino acid profile

Serum biochemical parameters, including GLU, ALB, ALT, AST, BUN, CRE, and ALP, were measured using spectrophotometric kits in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiangcheng Biotechnology Institute, Jiangsu Province, China) and determined using an Automatic Biochemistry Radiometer (Au640, Olympus).

Twenty amino acids in serum were determined by LC–MS/MS (HPLC Ultimate3000 and 3200 QTRAP LC–MS/MS) as described previously [68].

Analysis of serum hormonal components

GH, IGF1, T-SOD, HP and GSH-Px were measured with the use of ELISA test kits (Beijing Laboratory Biotech Co., LTD, China).

Determination of jejunal morphology

Segments (2 cm) of the jejunum were cut and fixed in 4 % neutral buffered 10 % formalin, processed using routine histological methods, and mounted in paraffin blocks [17, 69]. Six-micrometer-thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). After dehydration, embedding, sectioning, and staining, villous height, crypt depth, and goblet cell and lymphocyte counts were measured with computer-assisted microscopy (Micrometrics TM; Nikon ECLIPSE E200, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification of nutrients transporter genes mRNA

Total RNA was isolated from liquid nitrogen-pulverized intestine tissue sample with TRIzol regent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of RNA was checked by 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis after staining with 10 μg/ml ethidium bromide. The RNA had an OD260:OD280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0. First-strand cDNA was synthesized with oligo (dT) 20 and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA).

Primers were designed with Primer 5.0 based on the cDNA sequence of the pig to produce an amplification product (Table 9). β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize target gene transcript levels. Real-time PCR analysis was performed as described previously [18]. In brief, 2 μL of cDNA template was added to a total volume of 25 μL containing 12.5 μL SYBR Green mix and 1 μmol/l each of forward and reverse primers. We used the following protocol: (i) pre-denaturation (10 s at 95 °C); (ii) amplification and quantification, repeated 40 cycles (5 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 60 °C); (iii) melting curve (60–99 °C with a heating rate of 0.1 °C S-1 and fluorescence measurement). The relative levels of genes were expressed as a ratio of mRNA as R = 2-(∆∆Ct). The efficiency of real-time PCR was determined by the amplification of a dilution series of cDNA according to the equation 10(-1/slope), and the results for target mRNA were consistent with those for β-actin. Negative controls were created by replacing cDNA with water.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS17.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA) [17, 19]. Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance followed by the Duncan’s multiple comparisons test. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Abbreviations

- DON:

-

Deoxynivalenol

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- ADFI:

-

Average daily feed intake

- F/G:

-

Feed/gain ratio

- GIT:

-

Gastro-intestinal tract

- PBS:

-

Physiological saline solution

- GLU:

-

Serum fasting blood glucose

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate amino transferase

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CRE:

-

Creatinine

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- GH:

-

Growth hormone

- IGF1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- T-SOD:

-

Total superoxide dismutase

- HP:

-

Haptoglobin

- GSH-Px:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- EAAT-3:

-

Excitatory amino acid transporter-3

- B0,+AT:

-

B0,+amino acid transporter

- SGLT-1:

-

Sodium-glucose transporter-1

- GLUT-2:

-

Glucose transporter-2

- PepT-1:

-

Dipeptide transporter-1

- ASCT2:

-

Na+-dependent neutral amino acid exchanger-2

- CAT-1:

-

Cationic amino acid transporter-1

- LAT-1:

-

y+ L-type amino acid transporter-1

- AFB1 :

-

Aflatoxin B1

- ZEN:

-

Zearalenone

- OCH:

-

Ochratoxins

- FB1 :

-

Fumonisins B1

References

Pestka JJ. Deoxynivalenol: mechanisms of action, human exposure, and toxicological relevance. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84(9):663–79.

Pestka JJ. Mechanisms of deoxynivalenol-induced gene expression and apoptosis. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2008;25(9):1128–40.

Rotter BA, Prelusky DB, Pestka JJ. Toxicology of deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin). J Toxicol Environ Health. 1996;48(1):1–34.

Maresca M. From the gut to the brain: journey and pathophysiological effects of the food-associated trichothecene mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. Toxins (Basel). 2013;5(4):784–820.

Ferrari L, Cantoni AM, Borghetti P, De Angelis E, Corradi A. Cellular immune response and immunotoxicity induced by DON (deoxynivalenol) in piglets. Vet Res Commun. 2009;33 Suppl 1:133–5.

Kinser S, Jia Q, Li M, Laughter A, Cornwell P, Corton JC, et al. Gene expression profiling in spleens of deoxynivalenol-exposed mice: immediate early genes as primary targets. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2004;67(18):1423–41.

Chaytor AC, See MT, Hansen JA, de Souza AL, Middleton TF, Kim SW. Effects of chronic exposure of diets with reduced concentrations of aflatoxin and deoxynivalenol on growth and immune status of pigs. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(1):124–35.

Pestka JJ, Lin WS, Miller ER. Emetic activity of the trichothecene 15-acetyldeoxynivalenol in swine. Food Chem Toxicol. 1987;25(11):855–8.

Hunder G, Schumann K, Strugala G, Gropp J, Fichtl B, Forth W. Influence of subchronic exposure to low dietary deoxynivalenol, a trichothecene mycotoxin, on intestinal absorption of nutrients in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 1991;29(12):809–14.

Awad WA, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Bohm J, Zentek J. Effects of B-trichothecenes on luminal glucose transport across the isolated jejunal epithelium of broiler chickens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2008;92(3):225–30.

Maresca M, Mahfoud R, Garmy N, Fantini J. The mycotoxin deoxynivalenol affects nutrient absorption in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2002;132(9):2723–31.

Sergent T, Parys M, Garsou S, Pussemier L, Schneider YJ, Larondelle Y. Deoxynivalenol transport across human intestinal Caco-2 cells and its effects on cellular metabolism at realistic intestinal concentrations. Toxicol Lett. 2006;164(2):167–76.

Pinton P, Accensi F, Beauchamp E, Cossalter AM, Callu P, Grosjean F, et al. Ingestion of deoxynivalenol (DON) contaminated feed alters the pig vaccinal immune responses. Toxicol Lett. 2008;177(3):215–22.

Kasuga F, Hara-Kudo Y, Saito N, Kumagai S, Sugita-Konishi Y. In vitro effect of deoxynivalenol on the differentiation of human colonic cell lines Caco-2 and T84. Mycopathologia. 1998;142(3):161–7.

Awad WA, Ghareeb K, Zentek J. Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of the feed contaminant deoxynivalenol on glucose absorption in broiler chickens. Vet J. 2014;1:198–0.

Awad WA, Aschenbach JR, Setyabudi FM, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Bohm J, Zentek J. In vitro effects of deoxynivalenol on small intestinal D-glucose uptake and absorption of deoxynivalenol across the isolated jejunal epithelium of laying hens. Poult Sci. 2007;86(1):15–20.

Yin J, Ren W, Duan J, Wu L, Chen S, Li T, et al. Dietary arginine supplementation enhances intestinal expression of SLC7A7 and SLC7A1 and ameliorates growth depression in mycotoxin-challenged pigs. Amino Acids. 2014;46(4):883–92.

Wu L, Wang W, Yao K, Zhou T, Yin J, Li T, et al. Effects of dietary arginine and glutamine on alleviating the impairment induced by deoxynivalenol stress and immune relevant cytokines in growing pigs. PLoS One. 2013;8(7), e69502.

Xiao H, Tan BE, Wu MM, Yin YL, Li TJ, Yuan DX, et al. Effects of composite antimicrobial peptides in weanling piglets challenged with deoxynivalenol: II. Intestinal morphology and function. J Anim Sci 2013;91(10):4750–56.

Weaver AC, See MT, Hansen JA, Kim YB, De Souza AL, Middleton TF, et al. The use of feed additives to reduce the effects of aflatoxin and deoxynivalenol on pig growth, organ health and immune status during chronic exposure. Toxins (Basel). 2013;5(7):1261–81.

Shi Y, Pestka JJ. Attenuation of mycotoxin-induced IgA nephropathy by eicosapentaenoic acid in the mouse: dose response and relation to IL-6 expression. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17(10):697–706.

Awad WA, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Bohm J, Zentek J. Influence of deoxynivalenol on the D-glucose transport across the isolated epithelium of different intestinal segments of laying hens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2007;91(5–6):175–80.

Danicke S, Valenta H, Klobasa F, Doll S, Ganter M, Flachowsky G. Effects of graded levels of Fusarium toxin contaminated wheat in diets for fattening pigs on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, deoxynivalenol balance and clinical serum characteristics. Arch Anim Nutr. 2004;58(1):1–17.

Diesing AK, Nossol C, Danicke S, Walk N, Post A, Kahlert S, et al. Vulnerability of polarised intestinal porcine epithelial cells to mycotoxin deoxynivalenol depends on the route of application. PLoS One. 2011;6(2), e17472.

Nejdfors P, Ekelund M, Jeppsson B, Westrom BR. Mucosal in vitro permeability in the intestinal tract of the pig, the rat, and man: species- and region-related differences. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(5):501–7.

Xiao H, Wu MM, Tan BE, Yin YL, Li TJ, Xiao DF, et al. Effects of composite antimicrobial peptides in weanling piglets challenged with deoxynivalenol: I. Growth performance, immune function and antioxidation capacity. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(10):4772–80

Danicke S, Brosig B, Kersten S, Kluess J, Kahlert S, Panther P, et al. The Fusarium toxin deoxynivalenol (DON) modulates the LPS induced acute phase reaction in pigs. Toxicol Lett. 2013;220(2):172–80.

Rohweder D, Kersten S, Valenta H, Sondermann S, Schollenberger M, Drochner W, et al. Bioavailability of the Fusarium toxin deoxynivalenol (DON) from wheat straw and chaff in pigs. Arch Anim Nutr. 2013;67(1):37–47.

Moore CJ, Blaney BJ, Spencer RA, Dodman RL. Rejection by pigs of mouldy grain containing deoxynivalenol. Aust Vet J. 1985;62(2):60–2.

Gutzwiller A. Effects of deoxynivalenol (DON) in the lactation diet on the feed intake and fertility of sows. Mycotoxin Res. 2010;26(3):211–5.

Tiemann U, Danicke S. In vivo and in vitro effects of the mycotoxins zearalenone and deoxynivalenol on different non-reproductive and reproductive organs in female pigs: a review. Food Addit Contam. 2007;24(3):306–14.

Muller G, Kielstein P, Rosner H, Berndt A, Heller M, Kohler H. Studies on the influence of combined administration of ochratoxin A, fumonisin B1, deoxynivalenol and T2 toxin on immune and defence reactions in weaner pigs. Mycoses. 1999;42(7–8):485–93.

Prelusky DB, Gerdes RG, Underhill KL, Rotter BA, Jui PY, Trenholm HL. Effects of low-level dietary deoxynivalenol on haematological and clinical parameters of the pig. Nat Toxins. 1994;2(3):97–104.

Overnes G, Matre T, Sivertsen T, Larsen HJ, Langseth W, Reitan LJ, et al. Effects of diets with graded levels of naturally deoxynivalenol-contaminated oats on immune response in growing pigs. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A. 1997;44(9–10):539–50.

Swamy HV, Smith TK, MacDonald EJ, Boermans HJ, Squires EJ. Effects of feeding a blend of grains naturally contaminated with Fusarium mycotoxins on swine performance, brain regional neurochemistry, and serum chemistry and the efficacy of a polymeric glucomannan mycotoxin adsorbent. J Anim Sci. 2002;80(12):3257–67.

Bergsjo B, Langseth W, Nafstad I, Jansen JH, Larsen HJ. The effects of naturally deoxynivalenol-contaminated oats on the clinical condition, blood parameters, performance and carcass composition of growing pigs. Vet Res Commun. 1993;17(4):283–94.

Smith TK, McMillan EG, Castillo JB. Effect of feeding blends of Fusarium mycotoxin-contaminated grains containing deoxynivalenol and fusaric acid on growth and feed consumption of immature swine. J Anim Sci. 1997;75(8):2184–91.

Young LG, McGirr L, Valli VE, Lumsden JH, Lun A. Vomitoxin in corn fed to young pigs. J Anim Sci. 1983;57(3):655–64.

Rotter BA, Thompson BK, Lessard M, Trenholm HL, Tryphonas H. Influence of low-level exposure to Fusarium mycotoxins on selected immunological and hematological parameters in young swine. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994;23(1):117–24.

Swamy HV, Smith TK, MacDonald EJ, Karrow NA, Woodward B, Boermans HJ. Effects of feeding a blend of grains naturally contaminated with Fusarium mycotoxins on growth and immunological measurements of starter pigs, and the efficacy of a polymeric glucomannan mycotoxin adsorbent. J Anim Sci. 2003;81(11):2792–803.

Goyarts T, Grove N, Danicke S. Effects of the Fusarium toxin deoxynivalenol from naturally contaminated wheat given subchronically or as one single dose on the in vivo protein synthesis of peripheral blood lymphocytes and plasma proteins in the pig. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44(12):1953–65.

Nyblom H, Berggren U, Balldin J, Olsson R. High AST/ALT ratio may indicate advanced alcoholic liver disease rather than heavy drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(4):336–9.

Wu G. Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids. 2009;37(1):1–17.

Wang W, Wu Z, Dai Z, Yang Y, Wang J, Wu G. Glycine metabolism in animals and humans: implications for nutrition and health. Amino Acids. 2013;45(3):463–77.

Wu G. Functional amino acids in growth, reproduction, and health. Adv Nutr. 2010;1(1):31–7.

Yin J, Ren W, Liu G, Duan J, Yang G, Wu L, et al. Birth oxidative stress and the development of an antioxidant system in newborn piglets. Free Radic Res. 2013;47(12):1027–35.

Robert L. Serum haptoglobin in clinical biochemistry: change of a paradigm. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2013;61(6):277–9.

Jiang SZ, Yang ZB, Yang WR, Gao J, Liu FX, Broomhead J, et al. Effects of purified zearalenone on growth performance, organ size, serum metabolites, and oxidative stress in postweaning gilts. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(10):3008–15.

Dinu D, Bodea GO, Ceapa CD, Munteanu MC, Roming FI, Serban AI, et al. Adapted response of the antioxidant defense system to oxidative stress induced by deoxynivalenol in Hek-293 cells. Toxicon. 2011;57(7–8):1023–32.

Mary VS, Theumer MG, Arias SL, Rubinstein HR. Reactive oxygen species sources and biomolecular oxidative damage induced by aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 in rat spleen mononuclear cells. Toxicology. 2012;302(2–3):299–307.

Boisclair YR, Rhoads RP, Ueki I, Wang J, Ooi GT. The acid-labile subunit (ALS) of the 150 kDa IGF-binding protein complex: an important but forgotten component of the circulating IGF system. J Endocrinol. 2001;170(1):63–70.

Kobayashi-Hattori K, Amuzie CJ, Flannery BM, Pestka JJ. Body composition and hormonal effects following exposure to mycotoxin deoxynivalenol in the high-fat diet-induced obese mouse. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(7):1070–8.

Amuzie CJ, Pestka JJ. Suppression of insulin-like growth factor acid-labile subunit expression–a novel mechanism for deoxynivalenol-induced growth retardation. Toxicol Sci. 2010;113(2):412–21.

Amuzie CJ, Shinozuka J, Pestka JJ. Induction of suppressors of cytokine signaling by the trichothecene deoxynivalenol in the mouse. Toxicol Sci. 2009;111(2):277–87.

Kolf-Clauw M, Castellote J, Joly B, Bourges-Abella N, Raymond-Letron I, Pinton P, et al. Development of a pig jejunal explant culture for studying the gastrointestinal toxicity of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol: histopathological analysis. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23(8):1580–4.

Awad WA, Bohm J, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Zentek J. Effects of feeding deoxynivalenol contaminated wheat on growth performance, organ weights and histological parameters of the intestine of broiler chickens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2006;90(1–2):32–7.

Piva A, Casadei G, Pagliuca G, Cabassi E, Galvano F, Solfrizzo M, et al. Activated carbon does not prevent the toxicity of culture material containing fumonisin B1 when fed to weanling piglets. J Anim Sci. 2005;83(8):1939–47.

Brown TP, Rottinghaus GE, Williams ME. Fumonisin mycotoxicosis in broilers: performance and pathology. Avian Dis. 1992;36(2):450–4.

Bouhet S, Oswald IP. The intestine as a possible target for fumonisin toxicity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(8):925–31.

Bracarense AP, Lucioli J, Grenier B, Drociunas Pacheco G, Moll WD, Schatzmayr G, et al. Chronic ingestion of deoxynivalenol and fumonisin, alone or in interaction, induces morphological and immunological changes in the intestine of piglets. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(12):1776–86.

Wu G. Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids. 2013;45(3):407–11.

Zhang J, Yin Y, Shu XG, Li T, Li F, Tan B, et al. Oral administration of MSG increases expression of glutamate receptors and transporters in the gastrointestinal tract of young piglets. Amino Acids. 2013;45(5):1169–77.

Robinson MB. The family of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters: a focus on the GLT-1/EAAT2 subtype. Neurochem Int. 1998;33(6):479–91.

Hwang ES, Hirayama BA, Wright EM. Distribution of the SGLT1 Na+/glucose cotransporter and mRNA along the crypt-villus axis of rabbit small intestine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181(3):1208–17.

Wright EM, Loo DD, Turk E, Hirayama BA. Sodium cotransporters. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8(4):468–73.

Daniel H. Molecular and integrative physiology of intestinal peptide transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:361–84.

Broer S. Amino acid transport across mammalian intestinal and renal epithelia. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(1):249–86.

Ruan Z, Lv Y, Fu X, He Q, Deng Z, Liu W, et al. Metabolomic analysis of amino acid metabolism in colitic rats supplemented with lactosucrose. Amino Acids. 2013;45(4):877–87.

Wang J, Chen L, Li P, Li X, Zhou H, Wang F, et al. Gene expression is altered in piglet small intestine by weaning and dietary glutamine supplementation. J Nutr. 2008;138(6):1025–32.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB127301), Key project of the natural science foundation of Hunan province (12JJ2014), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31402088, 31330075 and 31201813).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

PL and TL conceived and designed the experiments. LW performed the experiments and analyzed the data. PL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LH, WR, JY and JD contributed reagents/materials/analytical tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Liao, P., He, L. et al. Growth performance, serum biochemical profile, jejunal morphology, and the expression of nutrients transporter genes in deoxynivalenol (DON)- challenged growing pigs. BMC Vet Res 11, 144 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0449-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0449-y