Abstract

Background

Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum has emerged in the Greater Mekong sub-region and poses a major global public health threat. Slow parasite clearance is a key clinical manifestation of reduced susceptibility to artemisinin. This study was designed to establish the baseline values for clearance in patients from Sub-Saharan African countries with uncomplicated malaria treated with artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs).

Methods

A literature review in PubMed was conducted in March 2013 to identify all prospective clinical trials (uncontrolled trials, controlled trials and randomized controlled trials), including ACTs conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa, between 1960 and 2012. Individual patient data from these studies were shared with the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) and pooled using an a priori statistical analytical plan. Factors affecting early parasitological response were investigated using logistic regression with study sites fitted as a random effect. The risk of bias in included studies was evaluated based on study design, methodology and missing data.

Results

In total, 29,493 patients from 84 clinical trials were included in the analysis, treated with artemether-lumefantrine (n = 13,664), artesunate-amodiaquine (n = 11,337) and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (n = 4,492). The overall parasite clearance rate was rapid. The parasite positivity rate (PPR) decreased from 59.7 % (95 % CI: 54.5–64.9) on day 1 to 6.7 % (95 % CI: 4.8–8.7) on day 2 and 0.9 % (95 % CI: 0.5–1.2) on day 3. The 95th percentile of observed day 3 PPR was 5.3 %. Independent risk factors predictive of day 3 positivity were: high baseline parasitaemia (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.16 (95 % CI: 1.08–1.25); per 2-fold increase in parasite density, P <0.001); fever (>37.5 °C) (AOR = 1.50 (95 % CI: 1.06–2.13), P = 0.022); severe anaemia (AOR = 2.04 (95 % CI: 1.21–3.44), P = 0.008); areas of low/moderate transmission setting (AOR = 2.71 (95 % CI: 1.38–5.36), P = 0.004); and treatment with the loose formulation of artesunate-amodiaquine (AOR = 2.27 (95 % CI: 1.14–4.51), P = 0.020, compared to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine).

Conclusions

The three ACTs assessed in this analysis continue to achieve rapid early parasitological clearance across the sites assessed in Sub-Saharan Africa. A threshold of 5 % day 3 parasite positivity from a minimum sample size of 50 patients provides a more sensitive benchmark in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to the current recommended threshold of 10 % to trigger further investigation of artemisinin susceptibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increasing availability of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) over the last decade has contributed to a substantial reduction in malaria morbidity and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1, 2]. However, the reduced efficacy of artemisinin against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Greater Mekong region [3–9] threatens to jeopardize the recent gains in malaria control and elimination. Identifying areas where decreased artemisinin susceptibility is emerging is critical to inform an adequate international response.

Delayed parasite clearance is the hallmark of artemisinin resistance [4, 10, 11]. However, its precise measurement requires frequent sampling and this is often logistically difficult to implement in resource-constrained settings [12]. Recently, specific mutations in the Kelch 13 (K13) gene have been shown to be highly correlated with the slow clearance phenotype in parasites from Northwest Cambodia [13] and other parts of the Greater Mekong sub-region [8, 14]. Although K13 mutations are present in Africa, the variants differ from those in Southeast Asia and their correlation with artemisinin resistance has yet to be substantiated [15–18]. The proportion of patients with persistent patent parasitaemia (parasite positivity rate, PPR) on day 3 has been proposed as a simple and pragmatic metric of choice for routine monitoring to identify suspected artemisinin resistance [19]. In depth clinical and parasitological assessments are warranted in sites where parasite positivity rate on day 3 (72 hours) exceeds 10 % in a study [19]. If less than 3 % of the patients in a site are still parasitaemic on day 3, artemisinin resistance is considered highly unlikely [20]. This threshold has been developed with data mostly from low transmission settings in Southeast Asia [20].

It is known that the speed of parasite clearance is influenced by a number of host, parasite and drug factors [10, 11, 21], including the level of acquired immunity [22–24], parasite density at presentation [20, 25–27], the quality of microscopy [28], the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles of the different artemisinin derivatives and the partner drugs [29].

Therefore, to assess the dynamics of early parasitological response after artemisinin combination therapy observed in SSA, parasite clearance data were compiled from patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria enrolled in ACT clinical efficacy trials conducted between 1999 and 2012. The aim was to provide a baseline of early parasitological response profiles so that sites at high risk (hot spots) for artemisinin resistance can be identified going forward, to inform malaria control and containment efforts.

Methods

Identification of studies for potential inclusion

Individual patient data

A literature review was conducted in PubMed in March 2013 and updated in 2014 to identify all published clinical trials of antimalarials since 1960. All antimalarial clinical trials published since 1960 were identified by the application of the key terms ((malaria OR plasmod*) AND (amodiaquine OR atovaquone OR artemisinin OR arteether OR artesunate OR artemether OR artemotil OR azithromycin OR artekin OR chloroquine OR chlorproguanil OR cycloguanil OR clindamycin OR coartem OR dapsone OR dihydroartemisinin OR duo-cotecxin OR doxycycline OR halofantrine OR lumefantrine OR lariam OR malarone OR mefloquine OR naphthoquine OR naphthoquinone OR piperaquine OR primaquine OR proguanil OR pyrimethamine OR pyronaridine OR quinidine OR quinine OR riamet OR sulphadoxine OR tetracycline OR tafenoquine)) through the PubMed library. All references containing any mention of antimalarial drugs were tabulated and manually checked to confirm prospective clinical trials. Studies on prevention or prophylaxis, reviews, animal studies or studies of patients with severe malaria or in pregnant women were excluded. When pdfs were available further details of the publications were reviewed, and basic details on the study methodology, treatment arms assessed and the study locations were documented. These are provided in the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) publication library [30]. Specific details of the studies with ACTs are available in Additional files 1 and 2. The year of the study was taken as the year in which the paper was published, although the start and end date of patient enrolment were also recorded. Where a specific site was not reported in the manuscript, the capital city of the country was used as the default location. Countries were grouped into four sub-regions: East; West; Central; and South Africa, as reported in the WHO World malaria report 2014 [1].

All research groups in the systematic review were contacted to share the entire dataset of their study with WWARN. Those who had contributed studies previously to the WWARN data repository were also invited to participate and asked whether they were aware of any unpublished or ongoing clinical trials involving ACTs, and these additional unpublished studies were also requested. Studies were included in the meta-analysis provided that they were: i) prospective clinical efficacy studies of uncomplicated P. falciparum (either alone or mixed infections with P. vivax); ii) clinical trials conducted in SSA with one of the following three ACTs: artemether-lumefantrine (AL) (six-dose), dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP) and one of the three formulations of artesunate-amodiaquine (AS-AQ): fixed dose combination (ASAQ-FDC), non-fixed dose combination in a loose formulation (ASAQ-loose NFDC) or non-fixed dose combination in a co-blister formulation (ASAQ-coblistered NFDC); and iii) parasitaemia was sampled at least on days 2 (48 hours) and 3 (72 hours) following treatment. Individual study protocols were available for all trials included, either from the publication or as a metafile submitted with the raw data. All data were uploaded to the WWARN repository and standardized using a methodology described in the clinical module data management and statistical analysis plan [31].

Definition of parameters assessed

Anaemia

Anaemia was defined according to WHO guidelines [32] (that is, haemoglobin cut-offs for moderate anaemia were 10 g/dl in children <5 years of age and 11 g/dl in older patients, and for severe anaemia were 7 and 8 g/dl, respectively). For studies where only haematocrit was measured, the following relationship was used to estimate haemoglobin: Haematocrit (%) = 5.62 + 2.60 × Haemoglobin (g/dl) [33].

Parasite positivity

A pre-defined algorithm was used to impute positivity status on days 2 or 3, if no observation of the blood film was recorded on that day [34]. For studies with frequent sampling, a patient was classified as being positive on days 1, 2 and 3 after enrolment if the measurements within a window of ± 3 hours of 24, 48 and 72 hours were positive.

Malaria transmission intensity

The study sites were classified into two categories, low/moderate and high malaria transmission, based on the observed re-infection rate and the parasite prevalence estimates obtained from the Malaria Atlas Project [35]. More information about this classification is available in Additional file 3.

Ethical approval

All data included in this analysis were obtained in accordance with ethical approvals from the country of origin. Ethical approval for pooled analysis of individual participant data was granted by the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OxTREC), based on the fact that all studies contributed to WWARN must have already obtained all necessary ethical approvals and informed consent.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out based on an a priori statistical plan [34]. The primary endpoint used in the analysis was microscopically defined parasite positivity on days 1, 2 and 3. The proportions of patients remaining parasitaemic on days 1, 2 and 3 were expressed as parasite positivity rates (PPRs) and were calculated for each study site separately using the individual patient data. The overall PPRs were calculated as a weighted average of the estimates from each of the individual study sites and associated confidence intervals (95 % CI) calculated by adjusting for within study clustering using the method described by Fleiss et al. [36]. Assuming baseline day 3 PPR equal to the upper limit of the 95 % CI around the observed PPR, we computed the maximum number of positive cases needed to be observed for the estimated 95 % CI to exclude this baseline for a given sample size, as described elsewhere [20].

Univariable and multivariable analyses of risk factors associated with parasite positivity status on days 1, 2 and 3 were conducted using generalized linear mixed model (logit link), in a one-stage analysis by combining all of the individual patient data. In order to account for within study clustering, study sites were fitted as random effects; the statistical significance of which was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified as the variance of the random effects using maximum likelihood method and the proportion of total variance contributed by the site-level variance component (ρ) was reported. Missing covariates were dealt with using multiple imputation methods. The number of imputations (m) was determined based on the fraction of missing information (γ) assuming 5 % loss in efficiency (η) using m ≥ γ*(η/1–η) [37]. Known confounders (age, parasitaemia and transmission setting) were kept in the model regardless of significance. Covariates examined at baseline included age, gender, fever (axillary, tympanic or rectal temperature >37.5 °C), parasitaemia, anaemia, gametocytemia, transmission setting, ACTs used for treatment, geographical region and year of the study. Any variables significant in univariable analysis (below 10 % level of significance) were kept for multivariable analysis; the decision of inclusion in the final model was assessed using a likelihood ratio test. In a sub-group of studies in which information was available on drug dosing, the effects of weight-adjusted doses (mg/kg) on parasite positivity status were evaluated after adjusting for the covariates significant in the multivariable analysis.

The robustness of the coefficients in the final multivariable model was examined using bootstrap sampling. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding one study site at a time and the coefficient of variation around the parameter estimates was calculated. The final model was used to simulate outcome for each patient and the observed PPRs were plotted against the simulated PPRs to assess model adequacy.

Continuous variables were compared between groups using generalized linear regression with study sites fitted as random effects. Data that were not normally distributed were compared with Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test. All statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 3.1.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using lme4 package.

Assessment of risk of potential bias

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, the risk of bias within studies was assessed based on: 1) study design (randomization, sequence generation, blinding); 2) microscopy methodologies for parasite quantification; and 3) the proportion of patients with (a) missing outcomes (missing outcome on days 2 and 3) and (b) missing baseline covariates (age, temperature, haemoglobin/haematocrit).

To assess whether the non-availability of some individual participant data could have biased the results, we extracted data on PPRs from studies not providing individual patient data and performed a two-stage meta-analysis of proportions using logit transformation; a continuity correction of 0.5 was applied to studies with zero cell count using meta package. Publication bias was assessed through the use of a funnel plot of the log-transformed odds ratio, the asymmetry of which was tested using Egger’s method.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

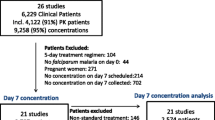

The systematic literature review identified 140 published clinical studies of ACT efficacy that were potentially relevant to this analysis. Researchers agreed to share individual patient data from 71 trials (50.7 %) including 25,731 patients (59.9 % of the targeted population). Additional data were available for 3,762 patients from 13 unpublished trials. In total, individual records were available from 29,493 patients enrolled in 27 different countries between 1999 and 2012 (Fig. 1). Fourteen studies (n = 4,177) had a single arm and the remaining 70 studies had at least two ACT arms (n = 25,376). Among these, 65 studies were randomized, 14 were non-randomized and randomization status was not reported in 5 studies. AL was administered to 46 % (n = 13,664) and DP to 15 % (n = 4,492) of patients. AS-AQ was administered in three different formulations: ASAQ-FDC (17 %, n = 4,907); ASAQ-loose NFDC (13 %, n = 3,925); and ASAQ-coblistered NFDC (9 %, n = 2,505). Thirty-five studies were conducted in West Africa (n = 10,676), 31 in East Africa (n = 8,331), 4 in Central Africa (n = 609), 4 in South Africa (n = 666), and the remaining 10 studies were multi-regional (n = 9,211).

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the included patients are given in Table 1. The mean age (years ± SD) was 6.7 ± 8.78, and was similar for patients treated with AL (7.4 ± 9.22) and AS-AQ (6.6 ± 8.60). The mean age was lower for patients treated with DP (4.9 ± 7.51), with 90 % (4,064/4,492) of patients treated with this regimen being less than 12 years old (P <0.05, linear regression). The median baseline parasitaemia was 20,200 parasites/μl (IQR: 6,320–51,520) with slight differences between treatment groups (Table 1). A high proportion (55.5 %, 11,918/21,479) of patients were anaemic at enrolment and 9 % (2,083/22,402) of the patients carried gametocytes at presentation (Table 1). After adjustment for age, both of these percentages were similar in the different treatment groups.

Observed parasite positivity rates (PPRs) on days 1, 2 and 3

The presence and density of parasites on day 1 could only be assessed in 55 % (16,196/29,493) of patients (52 studies). The overall parasite clearance rate for all studies was rapid. The PPR decreased from 59.7 % (95 % CI: 54.5–64.9) on day 1 (10,099/16,916) to 6.7 % (95 % CI: 4.8–8.7) on day 2 (1,853/27,496) and 0.9 % (95 % CI: 0.5–1.2) on day 3 (253/28,580). The PPRs on days 1, 2 and 3 were similar for AL, DP and ASAQ-FDC, but higher for the non-fixed formulations of AS-AQ on days 2 and 3 (Table 2). Compared to patients older than 12 years, children from 1 to 5 years had the highest PPR on day 1 (64 %, 6,430/10,053, P <0.001) and day 2 (7.5 %, 1,176/15,677, P <0.001), but there was no age-related difference on day 3. Patients with an initial parasite density >100,000 parasites/μl had a PPR of 82.7 % (1,494/1,807) on day 1, 14.3 % (385/2,696) on day 2 and 1.3 % (37/2,752) on day 3. The corresponding proportions for patients with parasitaemia less than 100,000 parasites/μl were 57.0 % (8,605/15,109), 5.9 % (1,468/24,800) and 0.8 % (216/25,828), respectively for days 1, 2 and 3 (all P <0.05). There were no regional differences or temporal trend in the PPRs on any days during the time period studied, that is, 1999–2012. A detailed summary of the PPRs for each of the treatment regimens stratified by country and calendar year is presented in Additional file 4. In total, there were 22 sites that had a PPR on day 3 exceeding 3 % (Table 3). The risk of day 3 parasitaemia exceeding 3 % was greatest in patients treated with ASAQ-loose NFDC (19.0 %, 8/42) and ASAQ-coblistered NFDC (11.1 %, 1/9) compared to 9.4 % (3/32) for AS-AQ FDC, 5.6 % (2/36) for DP and 7.6 % (8/105) for AL (Table 3). At two sites, the day 3 PPR was higher than 10 %: Miandrivazo, Madagascar, 2006 (n = 68, PPR = 10.3 %, ASAQ-loose NFDC) and Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2005 (n = 101, PPR = 30.1 %, ASAQ-coblistered NFDC) (Fig. 2).

Parasite positivity rates (PPRs) on days 2 and 3 following treatment administration. Boxplot showing PPRs for each of the ACTs separately. Only studies with sample size >25 patients were considered for the plot. There were two study sites with day 3 PPR >10 %, both of these sites used the non-fixed presentations of AS-AQ. ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; AL, artemether-lumefantrine; AS-AQ, artesunate-amodiaquine; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; PPR, parasite positivity rate

Risk factors associated with the parasite positivity status

The independent risk factors for parasite positivity were similar on days 1 and 2 (see Additional file 4: Table S6 for details on day 1 and Table 4 for day 2). After adjusting for confounding factors, patients treated with AL were at an increased risk of remaining parasitaemic on day 2 (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.21 (95 % CI: 1.01–1.44), P = 0.040) compared to those treated with DP or those treated with ASAQ-FDC (AOR = 1.33 (95 % CI: 1.08–1.63), P = 0.005). Similarly, patients treated with ASAQ-loose NFDC had an increased risk of remaining parasitaemic on day 2 compared to DP (AOR = 1.46 (95 % CI: 1.05–2.01), P = 0.022) and compared to ASAQ-FDC (AOR = 1.61 (95 % CI: 1.14–2.29), P = 0.007). In the same multivariable model, patients from low/moderate transmission sites were also at greater risk of remaining parasitaemic on day 2 compared to those from high transmission sites (AOR = 1.88 (95 % CI: 1.09–3.24), P = 0.024) (Fig. 3).

Probability of remaining parasitaemic (%) on days 2 and 3 for a given baseline parasitaemia in areas with different levels of transmission for children from 1 to 5 years of age. The probability of remaining positive on a given day was generated using coefficients from the final multivariable logistic regression with random effects for study sites. Zero study site effect was assumed for generating the predicted risk. The difference in risk of positivity for low/moderate setting has been given as δ and associated 95 % confidence interval presented

In multivariable analysis, the risk of being parasitaemic on day 3 increased with baseline parasitaemia (AOR = 1.16 (95 % CI: 1.08–1.25), for every 2-fold increase in parasite density, P <0.001), fever (AOR = 1.50 (95 % CI: 1.06–2.13), P = 0.022), severe anaemia (Hb < 7 g/dl) (AOR = 2.04 (95 % CI: 1.21–3.44), P = 0.008) and being from areas of low/moderate transmission (AOR = 2.71 (95 % CI: 1.38–5.36, P = 0.004 compared to high transmission areas); see Table 5. Patients treated with ASAQ-loose NFDC were at 2.27-fold ((95 % CI: 1.14–4.51), P = 0.020) increased risk of being parasitaemic on day 3 compared to patients treated with DP and 3.36-fold ((95 % CI: 1.61–6.98), P = 0.001) higher risk compared to patients treated with ASAQ-FDC. Similarly, patients treated with ASAQ-coblistered NFDC were at 4.18-fold ((95 % CI: 1.28–13.68), P = 0.017) greater risk compared to those treated with ASAQ-FDC (Table 5).

Effect of weight adjusted (mg/kg) artemisinin components

The weight adjusted drug dosage (mg/kg) was available in 72 % (21,310/29,493) of the patients. Adjusted for the baseline confounders, the mg/kg dose of artemisinin component was not associated with the risk of parasite positivity on any day for patients treated with DP or AS-AQ (either for the fixed or the loose combinations). However, in patients treated with AL, an increased mg/kg dose of artemether was associated with a lower risk of patent parasitaemia only on day 1. Every unit increase in daily mg/kg artemether dose reduced the risk of parasite positivity by 5 % ((95 % CI: 1–7 %), P = 0.003) (see Additional file 4: Table S10).

Derivation of day 3 PPR threshold for suspected diminished artemisinin susceptibility

The overall day 3 PPR was 0.58 % (95 % CI: 0.34–0.82) for AL, 0.54 % (95 % CI: 0.14–0.94) for ASAQ-FDC and 0.77 % (95 % CI: 0.11–1.42) for DP. In studies with a sample size greater than 50 patients, the observed PPR was unlikely to exceed 5 % positivity on day 3 (Fig. 4). However, in studies with fewer than 50 patients, the variance around the estimate was extremely wide, so a reliable estimate could not be derived (Table 6, Fig. 4).

Maximum day 3 parasite positivity rate (PPR) possible for each of the treatment regimens for a given study sample size. Worst-case estimates were used for the analysis, that is, an upper limit of 95 % CI was assumed to be the true underlying parasite positivity rate on day 3, which was 0.82 %, 0.94 % and 1.42 % for AL, ASAQ-FDC and DP, respectively. The horizontal solid line represents 10 % day 3 WHO threshold and the dotted horizontal line represents 5 % day 3 PPR. The saw-tooth spikes are the result of rounding to the nearest whole number. ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; AL, artemether-lumefantrine; ASAQ-FDC, fixed dose combination; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; PPR, parasite positivity rate

Assessment of potential bias

Attrition biases of the included studies are presented in Additional file 1. Sensitivity analyses showed that exclusion of any of the studies did not change the main conclusions of the analysis (Additional file 4: Table S12). In addition, parameter estimates obtained from bootstrap sampling were similar to the estimates from final multivariable models (Additional file 4: Figures S2,3). Combining studies with and without individual patient data concluded similar results to those in which only studies with individual patient data were available (Additional file 4: Table S13). Funnel plots of the log-transformed odds ratio against standard error were symmetric suggesting low risk of publication bias (Additional file 4: Figures S7,8).

Discussion

This large pooled analysis of nearly 30,000 patients from trials conducted before 2012 highlights that parasite clearance after treatment with an ACT is still extremely rapid in Sub-Saharan Africa. More than 90 % of the patients were aparasitaemic by day 2 and 99 % by day 3, consistent with previous reports demonstrating rapid parasite clearance after treatment with ACTs in high transmission settings [20, 26].

In areas of intense transmission, immunity develops at a relatively young age [38, 39] and is a key determinant of the antimalarial therapeutic response [40]. Our results show that patients from areas of low/moderate transmission were at greater risk of parasite positivity compared to patients from high transmission regions, a likely reflection of the influence of immunity in the early therapeutic response. Almost 80 % of patients were less than 12 years old, an age group with the highest risk of parasitaemia on days 1 and 2. Every 2-fold increase in parasite density was associated with 1.5 to 1.2-fold risk of failing to clear parasitaemia on days 1 to 3, respectively. Similarly, patients with fever at enrolment had a higher risk of persistent parasitaemia. Fever and parasitaemia are closely correlated, with symptoms manifesting in those exceeding a pyrogenic threshold, this threshold rising as the host experiences repeated infections and acquires a degree of immunity. However, independent of baseline parasitaemia, patients with fever on presentation showed slower parasitological clearance as has been noted previously and hypothesized to relate to a reduced host immunity [25, 27]. The results of these analyses emphasize the importance of transmission intensity in the development of immunity and the pivotal role of acquired immunity in modulating early parasitological response to treatment with ACTs [22, 23]. Patients who were severely anaemic at presentation were also at greater risk of remaining parasitaemic on days 1 to 3 compared to those who were non-anaemic. Severe anaemia is associated with recurrent episodes of malaria and can arise as a consequence of treatment failure, hence may be indicative of a poor immune response or emerging parasite resistance [41]. In addition, co-infections with helminths, poor socioeconomic status and malnutrition may further compound the effects [42]. Further research is needed to understand the underlying biological pathways and will be explored in the WWARN Haematology Study Group [43].

After adjusting for these parasite and host factors, the risks of persistent parasitaemia on days 1 and 2 were higher in patients treated with AL compared to those treated with DP and ASAQ-FDC, but this difference was no longer apparent by day 3. Artemether is a lipophilic compound and is more slowly absorbed than artesunate or dihydroartemisinin, and this difference may explain the slower action of AL [44, 45]. Moreover, artemether is delivered in a lower dose which is split into twice daily target dosing of 1.7 mg/kg compared with the once daily dose of 4 mg/kg dose of dihydroartemisinin in DP and 4 mg/kg dose of artesunate in AS-AQ [46, 47]. This dose effect was apparent on day 1 but not on days 2 and 3, with every unit increase in artemether dose reducing the risk of day 1 positivity by 5 %, a result observed previously in a large pooled analysis [48]. Similarly, patients treated with ASAQ-loose NFDC were at increased risk of slow clearance on days 2 and 3 compared to those treated with ASAQ-FDC (and DP) despite the target dose of artesunate being the same (4 mg/kg/day) across all the formulations. The differences in the mg/kg amodiaquine dosage between different formulations were found not to affect early parasitological responses (data not shown). The elevated risk observed with the NFDCs could be associated with several factors including drug quality and tablet splitting required for many children, which could potentially lead to dosing inaccuracy or reduced compliance [49, 50].

The study period encompasses 1999 to 2012, covering the period during the introduction of the large scale deployment of ACTs across Africa. Overall, there were no differences in the early parasitological response post-ACT treatment in different sub-regions of SSA and there was no evidence of decreased susceptibility to artemisinin in Africa over this time period. Nevertheless, there were 22 sites where PPR on day 3 exceeded 3 % (the threshold below which artemisinin resistance in unlikely), with two sites exceeding day 3 PPR of 10 % (the WHO threshold for suspected partial resistance). In Miandrivazo (Madagascar), the reported PPR was 10.3 % in 2006 [51] but less than 1 % in a subsequent trial in the same region (Tsiroanomandidy) [52]. In Yaoundé, a PPR of 30 % was reported in 2005 [53]; however, in a study conducted at the same site 7 years later [54], the PPR was 2.9 % (95 % CI: 3.7–27.2, 2/68) suggesting that the high PPR observed in our dataset could have been an artefact. High day 3 PPR does not necessarily relate to a change in parasite susceptibility to artemisinin; other factors, such as declining immunity [55], poor drug quality [56] and variable quality of microscopy [57] can play major roles. Studies with more intense blood sampling are needed in areas of delayed parasite clearance [10, 12]. These will require better definition of the parasite clearance, complementary in vitro testing [58] and molecular analysis [13] to rule out any change in artemisinin susceptibility.

Our analysis has a number of limitations. First, the literature search was limited to prospective clinical trials indexed in PubMed and some relevant studies may have been overlooked. However, we actively looked for relevant trials (unpublished) and the research groups contacted represent the majority of the malaria community, which is relatively small and highly interactive. It is highly unlikely that any studies were missed. The assessment of publication bias (PB) showed that effect sizes were symmetrical suggesting low risk of bias in studies included. Of the 140 trials identified, individual patient data were available for inclusion for 71 of the published studies (50.7 %). To address this potential bias, included studies were compared with the published studies that were not available. There were no apparent differences in patient population and/or outcomes between the studies included and those where individual patient data were not available. Reassuringly, the results from two-stage meta-analyses, which combined studies with and without individual patient data, were also similar to the results obtained from studies where only individual patient data were available, suggesting that systematic attrition bias was unlikely. A second issue is that, although the days of follow-up were recorded in the studies, the actual time of blood collection was not. Daily samples were taken over a range of times and the interval between days is likely to have varied significantly from the desired 24-, 48- or 72-hour timelines. Third, the data used rely on quantitative microscopy and quality control on microscopy procedures were reported in only 60 % of the studies. Accurate recording of the time of sampling, harmonizing microscopy procedures and appropriate quality control procedures could greatly improve the precision of the parasite clearance time [11]. To facilitate this process, a new microscopy procedure has been developed recently to improve comparability of results between groups [59]. Finally, no data on drug levels were available to assess whether patients achieved therapeutic blood concentrations. However, absorption of artemisinin derivatives in uncomplicated malaria is usually good and in the majority (89 %) of studies, drug administration was observed fully or partially by the clinical team.

This large dataset provided a unique opportunity to identify a threshold for day 3 parasite positivity based upon African studies, below which artemisinin resistance is highly unlikely. The upper limit of the 95 % CI for day 3 PPR, indicative of the worst-case scenario, defines maximum PPR which could be observed reliably in a clinical trial. This threshold was vulnerable to the initial parasitaemia and study sample size. For example, in studies with 50 or less patients, the confidence interval around any threshold value was wide, hence its predictive utility under those circumstances is limited. Our results demonstrate that the 95th percentile of the observed day 3 PPR in Africa was 5.3 %, substantially lower than the currently recommended threshold of 10 % for suspected partial artemisinin resistance. These findings strongly suggest that a ‘one size fits all’ threshold of 10 % should be used with caution. A simple sensitive parameter indicative of potential artemisinin resistance would be an extremely useful surveillance tool. Our analysis suggests that although the widely proposed 10 % threshold would be specific, it lacks sensitivity in detecting an early stage changes of delayed parasite clearance. Moreover, a previous WWARN meta-analysis of published literature showed that the PPR on day 3 over the same period (1999–2012) was much lower in Africa (1 %) compared to Asia (3.8 %) [26]. A threshold of 5 % provides greater sensitivity and an early warning signal in SSA. Modelling will help to refine this threshold further [21, 60].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this pooled analysis provides critical baseline information regarding early parasitological response post-treatment with ACTs in SSA. The assessment of the host, parasite and drug determinants which influence the early parasitological response can provide evidence-based guidance for monitoring the early signs of artemisinin resistance and effective case management that will be critical in optimizing malaria control and containment efforts.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- AL:

-

Artemether-lumefantrine

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- AQ:

-

Amodiaquine

- AS:

-

Artesunate

- AS-AQ:

-

Artesunate-amodiaquine

- ASAQ-coblistered NFDC:

-

Non-fixed dose combination in a co-blister formulation

- ASAQ-FDC:

-

Fixed dose combination

- ASAQ-loose NFDC:

-

Non-fixed dose combination in a loose formulation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DP:

-

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine

- IPD:

-

Individual participant data

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LLIN:

-

Long-lasting insecticidal net

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OxTREC:

-

Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee

- PPR:

-

Parasite positivity rate

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RSD:

-

Relative standard deviation

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TDR:

-

The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WWARN:

-

Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network

References

World Health Organization (WHO). World malaria report 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Noor AM, Kinyoki DK, Mundia CW, Kabaria CW, Mutua JW, Alegana VA, et al. The changing risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection in Africa: 2000–10: a spatial and temporal analysis of transmission intensity. Lancet. 2014;383:1739–47.

Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM, et al. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2619–20.

Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–67.

Phyo AP, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S, Mc Gready R, et al. Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2012;379:1960–6.

Leang R, Barrette A, Bouth DM, Menard D, Abdur R, Duong S, et al. Efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Cambodia, 2008 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:818–26.

Kyaw MP, Nyunt MH, Chit K, Aye MM, Aye KH, Lindegardh N, et al. Reduced susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in southern Myanmar. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57689.

Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–23.

Tun KM, Imwong M, Lwin KM, Win AA, Hlaing TM, Hlaing T, et al. Spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Myanmar: a cross-sectional survey of the K13 molecular marker. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;5:415–21.

Flegg JA, Guerin PJ, White NJ, Stepniewska K. Standardizing the measurement of parasite clearance in falciparum malaria: the parasite clearance estimator. Malar J. 2011;10:339.

White NJ. The parasite clearance curve. Malar J. 2011;10:278.

Flegg JA, Guérin PJ, Nosten F, Ashley EA, Phyo AP, Dondorp AM, et al. Optimal sampling designs for estimation of Plasmodium falciparum clearance rates in patients treated with artemisinin derivatives. Malar J. 2013;12:411.

Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois A-C, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–5.

Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Arze C, Cummings MP, Silva JC, Dondorp AM, et al. Independent emergence of Plasmodium falciparum artemisinin resistance mutations in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis. 2014;211:670–9.

Conrad MD, Bigira V, Kapisi J, Muhindo M, Kamya MR, Havlir DV, et al. Polymorphisms in K13 and falcipain-2 associated with artemisinin resistance are not prevalent in Plasmodium falciparum isolated from Ugandan children. PLoS One. 2014;9.

Kamau E, Campino S, Amenga-Etego L, Drury E, Ishengoma D, Johnson K, et al. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2014;211:1352–5.

Taylor SM, Parobek CM, DeConti DK, Kayentao K, Coulibaly SO, Greenwood BM, et al. Absence of putative artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Sub-Saharan Africa: a molecular epidemiologic study. J Infect Dis. 2014;211:680–8.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN). Tracking resistance. [http://www.wwarn.org/tracking-resistance/]

World Health Organization (WHO). Status report on artemisinin resistance. Geneva: WHO; 2014 [http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/status_rep_artemisinin_resistance_sep2014.pdf?ua=1]

Stepniewska K, Ashley E, Lee SJ, Anstey N, Barnes KI, Binh TQ, et al. In vivo parasitological measures of artemisinin susceptibility. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:570–9.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) Parasite Clearance Study Group. Baseline data of parasite clearance in patients with falciparum malaria treated with an artemisinin derivative: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Malaria Journal. 2015; In Press.

Maiga AW, Fofana B, Sagara I, Dembele D, Dara A, Traore OB, et al. No evidence of delayed parasite clearance after oral artesunate treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:23–8.

Lopera-Mesa TM, Doumbia S, Chiang S, Zeituni AE, Konate DS, Doumbouya M, et al. Plasmodium falciparum clearance rates in response to artesunate in Malian children with malaria: effect of acquired immunity. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1655–63.

Ndour PA, Lopera-Mesa TM, Diakité SAS, Chiang S, Mouri O, Roussel C, et al. Plasmodium falciparum clearance is rapid and pitting independent in immune Malian children treated with artesunate for malaria. J Infect Dis. 2014;211:290–7.

Sowunmi A, Adewoye EO, Gbotsho GO, Happi CT, Sijuade A, Folarin OA, et al. Factors contributing to delay in parasite clearance in uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. Malar J. 2010;9:53.

Das D, Price RN, Bethell D, Guerin PJ, Stepniewska K. Early parasitological response following artemisinin-containing regimens: a critical review of the literature. Malar J. 2013;12:125.

Muhindo MK, Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Talisuna A, Osilo E, Orukan F, et al. Early parasite clearance following artemisinin-based combination therapy among Ugandan children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2014;13:32.

Fairhurst RM, Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Hallett R, Vennerstrom JL, Duong S, et al. Artemisinin-resistant malaria: research challenges, opportunities, and public health implications. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:231–41.

White NJ. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1413–22.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN). WWARN Clinical Trials Publication Library: Methodology. [http://www.wwarn.org/tools-resources/literature-reviews/wwarn-clinical-trials-publication-library/methodology]

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN). Clinical module: data management and statistical analysis plan. Version 1.2. Oxford: WWARN; 2012.

World Health Organization (WHO). Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf]

Lee SJ, Stepniewska K, Anstey N, Ashley E, Barnes K, Binh TQ, et al. The relationship between the haemoglobin concentration and the haematocrit in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2008;7:149.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN). Statistical analysis plan artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) in Africa baseline early parasitological response (EPF) individual patient pooled analysis Version 1. Oxford: WWARN; 2012.

Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL, Guerra CA, Elyazar IR, Johnston GL, et al. A new world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2010. Malar J. 2011;10:378.

Fleiss J, Paik M, LB H. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

Db R. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1987.

Smith T, Felger I, Kitua A, Tanner M, Beck HP. Dynamics of multiple Plasmodium falciparum infections in infants in a highly endemic area of Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:35–9.

Snow RW, Marsh K. New insights into the epidemiology of malaria relevant for disease control. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:293–309.

Greenhouse B, Slater M, Njama-Meya D, Nzarubara B, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C, Clark TD, et al. Decreasing efficacy of antimalarial combination therapy in Uganda is explained by decreasing host immunity rather than increasing drug resistance. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:758–65.

Price RN, Simpson JA, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Hkirjaroen L, ter Kuile F, et al. Factors contributing to anemia after uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:614–22.

Matangila JR, Doua JY, Linsuke S, Madinga J. Inocêncio Da Luz R, Van Geertruyden J-P, et al. Malaria, schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminth burden and their correlation with anemia in children attending primary schools in Kinshasa. Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110789.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN): Haematology Study Group. [http://www.wwarn.org/working-together/study-groups/haematology-study-group]

White NJ, van Vugt M, Ezzet F. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and pharmacodynamics of artemether-lumefantrine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:105–25.

Ezzet F, van Vugt M, Nosten F, Looareesuwan S, White NJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lumefantrine (benflumetol) in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:697–704.

World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Price RN. Potential of artemisinin-based combination therapies to block malaria transmission. J Infect Dis. 2013. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit079.

WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN) AL Dose Impact Study Group. The effect of dose on the antimalarial efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine: a systematic review and pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:692–702.

Elliott I, Mayxay M, Yeuichaixong S, Lee SJ, Newton PN. The practice and clinical implications of tablet splitting in international health. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:754–6.

Newton PN, Schellenberg D, Ashley EA, Ravinetto R, Green MD, Kuile FOT, et al. Quality assurance of drugs used in clinical trials: proposal for adapting guidelines. BMJ. 2015;350:h602.

Ménard D, Ratsimbasoa A, Randrianarivelojosia M, Rabarijaona L-P, Raharimalala L, Domarle O, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of antimalarial drugs recommended by the National Malaria Control Programme in Madagascar: up-dated baseline data from randomized and multi-site clinical trials. Malar J. 2008;7:55.

Ndiaye JL, Randrianarivelojosia M, Sagara I, Brasseur P, Ndiaye I, Faye B, et al. Randomized, multicentre assessment of the efficacy and safety of ASAQ - a fixed-dose artesunate-amodiaquine combination therapy in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2009;8:125.

Ndiaye JL, Faye B, Diouf AM, Kuete T, Cisse M, Seck PA, et al. Randomized, comparative study of the efficacy and safety of artesunate plus amodiaquine, administered as a single daily intake versus two daily intakes in the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2008;7:16.

Tahar R, Almelli T, Debue C, Foumane Ngane V, Djaman Allico J, Whegang Youdom S, et al. Randomized trial of artesunate-amodiaquine, atovaquone-proguanil, and artesunate-atovaquone-proguanil for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1962–71.

Borrmann S, Sasi P, Mwai L, Bashraheil M, Abdallah A, Muriithi S, et al. Declining responsiveness of Plasmodium falciparum infections to artemisinin-based combination treatments on the Kenyan coast. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26005.

Tabernero P, Fernández FM, Green M, Guerin PJ, Newton PN. Mind the gaps - the epidemiology of poor-quality anti-malarials in the malarious world - analysis of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network database. Malar J. 2014;13:139.v

Murphy SC, Shott JP, Parikh S, Etter P, Prescott WR, Stewart VA. Malaria diagnostics in clinical trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:824–39.

Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, et al. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1043–9.

Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR)/World Health Organization (WHO). Methods manual. Microscopy for the detection, identification and quantification of malaria parasites on stained thick and thin blood films in research settings. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/microscopy_detec_ident_quantif/en/]

White LJ, Flegg JA, Phyo AP, Wiladpai-Ngern JH, Bethell D, Plowe C, et al. Defining the In vivo phenotype of artemisinin-resistant falciparum malaria: a modelling approach. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001823.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and all the staff that participated in these clinical trials at all the sites, and the WWARN team for technical and administrative support.

The WWARN ACT Africa Baseline Study Group writing committee

Prabin Dahal, Umberto d’Alessandro, Grant Dorsey, Philippe J Guerin, Christian Nsanzabana, Ric N Price, Carol H Sibley, Kasia Stepniewska and Ambrose O Talisuna.

Salim Abdulla1, Ishag Adam2, George O Adjei3, Martin A Adjuik4, Bereket Alemayehu5, Richard Allan6, Emmanuel Arinaitwe7, Elizabeth A Ashley8, Mamadou S Ba9, Hubert Barennes10,11, Karen I Barnes12,13, Quique Bassat14,15, Elisabeth Baudin8, Nicole Berens-Riha16,17, Anders Björkman18, François Bompart19, Maryline Bonnet20, Steffen Borrmann21,22,23, Teun Bousema24,25, Philippe Brasseur26, Hasifa Bukirwa27, Francesco Checchi8, Prabin Dahal28,29, Umberto D'Alessandro30,31,32, Meghna Desai33, Alassane Dicko34,35, Abdoulaye A Djimdé34, Grant Dorsey36, Ogobara K Doumbo34, Chris J Drakeley23, Stephan Duparc37, Teferi Eshetu15,38, Emmanuelle Espié8, Jean-François Etard8,39, Abul M Faiz40, Catherine O Falade41, Caterina I Fanello42, Jean‐François Faucher43,44,45, Babacar Faye9, Oumar Faye9, Scott Filler46, Jennifer A Flegg28,47, Bakary Fofana34, Carole Fogg48, Nahla B Gadalla24,49,50, Oumar Gaye9, Blaise Genton51,52, Peter W Gething53, José P Gil54,55,56, Raquel González14,15, Francesco Grandesso8, Bryan Greenhouse36, Brian Greenwood32, Anastasia Grivoyannis57, Philippe J Guerin28,29, Jean-Paul Guthmann58, Kamal Hamed59, Sally Hamour60, Simon I Hay61,62,63, Eva Maria Hodel51,64, Georgina S Humphreys28,29, Jimee Hwang33,65, Maman L Ibrahim66, Daddi Jima67, Joel J Jones68, Vincent Jullien69, Elizabeth Juma70, Patrick S Kachur33, Piet A Kager71, Erasmus Kamugisha72, Moses R Kamya73, Corine Karema74, Kassoum Kayentao34, Jean-René Kiechel75, Fred Kironde76, Poul-Erik Kofoed77,78, Peter G Kremsner22,79, Sanjeev Krishna80, Valérie Lameyre19, Bertrand Lell22,79, Angeles Lima81, Michael Makanga82, ElFatih M Malik83, Kevin Marsh21,29, Andreas Mårtensson18,84,85, Achille Massougbodji86, Hervé Menan87, Didier Menard88, Clara Menéndez14,15, Petra F Mens71,89, Martin Meremikwu90,91, Clarissa Moreira28,29, Carolyn Nabasumba8,92, Michael Nambozi93, Jean-Louis Ndiaye9, Billy E Ngasala94,95, Frederic Nikiema96, Christian Nsanzabana28,29, Francine Ntoumi22,97, Mary Oguike24, Bernhards R Ogutu98, Piero Olliaro29,99, Sabah A Omar100, Jean-Bosco Ouédraogo10,96, Seth Owusu-Agyei101, Louis K Penali102, Mbaye Pene9, Judy Peshu21, Patrice Piola103, Christopher V Plowe104, Zul Premji94, Ric N Price28,29,105, Milijaona Randrianarivelojosia106, Lars Rombo107,108,109, Cally Roper110, Philip J Rosenthal36, Issaka Sagara34, Albert Same-Ekobo111, Patrick Sawa112, Henk DFH Schallig89, Birgit Schramm8, Amadou Seck102, Seif A Shekalaghe1,113, Carol H Sibley28,114, Véronique Sinou115, Sodiomon B Sirima116, Fabrice A Somé96, Doudou Sow9, Sarah G Staedke7,117, Kasia Stepniewska28,29, Colin J Sutherland24, Todd D Swarthout118, Khadime Sylla9, Ambrose O Talisuna119,120, Walter RJ Taylor99,121, Emmanuel A Temu6,51,122, Julie I Thwing33, Roger CK Tine9, Halidou Tinto10,96, Silva Tommasini123, Offianan A Touré124, Johan Ursing77,95, Michel T Vaillant125,126, Giovanni Valentini123, Ingrid Van den Broek118,127, Michele Van Vugt128, Stephen A Ward129, Peter A Winstanley130, William Yavo131,132, Adoke Yeka27, Yah M Zolia68 and Issaka Zongo96.

1Ifakara Health Institute, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

2Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan

3Centre for Tropical Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, Ghana

4INDEPTH Network Secretariat, Accra, Ghana

5International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Programs, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

6The MENTOR Initiative, Crawley, UK

7Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda

8Epicentre, Paris, France

9Department of Parasitology and Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, University Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal

10Centre Muraz, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso

11French Foreign Affairs, Biarritz, France

12WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), Pharmacology module, Cape Town, South Africa

13Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

14Centro de Investigacao em Saude de Manhiça, Manhiça, Mozambique

15ISGlobal, Barcelona Centre for International Health Research (CRESIB), Hospital Clínic - Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

16Division of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Medical Center of the University of Munich (LMU), Munich, Germany

17German Centre for Infection Research (DZIF) at LMU, Munich, Germany

18Department of Microbiology, Tumour and Cell Biology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

19Direction Accès au Médicament/Access to Medicines, Sanofi Aventis, Gentilly, France

20Epicentre, Geneva, Switzerland

21Kenya Medical Research Institute/Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kilifi, Kenya

22Institute for Tropical Medicine, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

23German Centre for Infection Research, Tübingen, Germany

24Department of Infection and Immunity, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

25Department of Medical Microbiology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Njimegen, the Netherlands

26Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Dakar, Sénégal

27Uganda Malaria Surveillance Project, Kampala, Uganda

28WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), Oxford, UK

29Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

30Unit of Malariology, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium

31Medical Research Council Unit, Fajara, the Gambia

32Department of Diseases Control, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

33Malaria Branch, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia

34Malaria Research and Training Center, Faculty of Medicine Pharmacy and Dentistry, University of Bamako, Bamako, Mali

35Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine Pharmacy and Dentistry, University of Bamako, Bamako, Mali

36Department of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

37Medicine for Malaria Venture, Geneva, Switzerland

38Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences and Pathology, Jimma University (JU), Jimma, Ethiopia

39Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Montpellier, France

40Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

41Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

42Mahidol-Oxford Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

43Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Mother and Child Health in the Tropics Research Unit, Paris, France

44PRES Sorbonne Paris Cité, Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France

45Department of Infectious Diseases, Besançon University Medical Center, Besançon, France

46The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Geneva, Switzerland

47School of Mathematical Sciences and Monash Academy for Cross and Interdisciplinary Mathematical Applications, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

48University of Portsmouth/Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Portsmouth, UK

49Department of Epidemiology, Tropical Medicine Research Institute, National Centre for Research, Khartoum, Sudan

50National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Rockville, MD, USA

51Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland

52Division of Infectious Diseases and Department of Ambulatory Care and Community Medicine, University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

53Spatial Ecology and Epidemiology Group, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

54Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Drug Resistance Unit, Section of Pharmacogenetics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

55Faculty of Sciences, Biosystems and Integrative Sciences Institute (BioISI), University of Lisboa, Campo Grande, Lisboa, Portugal

56The Harpur College of Arts and Sciences, Binghamton University, The State University of New York, Binghamton, NY, USA

57Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

58Département des Maladies Infectieuses, Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint Maurice, France

59Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA

60UCL Centre for Nephrology, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

61Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

62Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

63Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

64Parasitology Department, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK

65Global Health Group, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

66Unité de Parasitologie, Centre de Recherche Médicale et Sanitaire, Niamey, Niger

67Federal Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

68National Malaria Control Programme, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Monrovia, Liberia

69Université Paris Descartes, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France

70Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya

71Centre for Infection and Immunity Amsterdam (CINIMA), Division of Infectious Diseases, Tropical Medicine and AIDS, Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

72Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania

73College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

74Malaria and Other Parasitic Diseases Division-RBC, Ministry of Health, Kigali, Rwanda 75Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, Geneva, Switzerland

76Departement of Biochemistry, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

77Projecto de Saúde de Bandim, Bissau, Guinea-Bissau

78Department of Paediatrics, Kolding Hospital, Kolding, Denmark

79Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné, Lambaréné, Gabon

80Institute for Infection and Immunity, St George’s, University of London, London, UK

81Médecins Sans Frontières, Operational Centre Barcelona – Athens, Barcelona, Spain

82European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), Cape Town, South Africa

83Federal Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan

84Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

85Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

86Centre d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Paludisme Associé à la Grossesse et à l’Enfant (CERPAGE), Faculté des Sciences de la Santé (FSS), Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Bénin

87Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

88Malaria Molecular Epidemiology Unit, Institut Pasteur in Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

89Royal Tropical Institute, KIT Biomedical Research, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

90Department of Paediatrics, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria

91Institute of Tropical Diseases Research and Prevention, Calabar, Nigeria

92Faculty of Medicine, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda

93Tropical Diseases Research Centre, Ndola, Zambia

94Department of Parasitology, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

95Malaria Research, Infectious Disease Unit, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

96Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé, Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso

97Fondation Congolaise pour la Recherche Médicale (FCRM), Faculté des Sciences de la Santé, Université Marien Ngouabi, Brazzaville, République du Congo

98Kenya Medical Research Institute/United States Army Medical Research Unit, Kisumu, Kenya

99UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (WHO/TDR), Geneva, Switzerland

100Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Centre for Biotechnology Research and Development, Nairobi, Kenya

101Kintampo Health Research Center, Kintampo, Ghana

102WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN)-West Africa Regional Centre, Dakar, Senegal

103Epidemiology Unit, Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, Antananarivo, Madagascar

104Howard Hughes Medical Institute/Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

105Menzies School of Health Research and Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia

106Malaria Research Unit, Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, Antananarivo, Madagascar

107Malaria Research Laboratory, Unit of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

108Department of Infectious Diseases Mälarsjukhuset 631 88 Eskilstuna, Sweden

109Centre for Clinical Research, Sörmland, Uppsala, Sweden

110Department of Pathogen Molecular Biology, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

111Faculté de Médecine et des Sciences Biomédicales, Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire de Yaoundé, Yaoundé, Cameroon

112Human Health Division, International Centre for insect physiology and Ecology, Mbita, Kenya

113Kilimanjaro Clinical Medical Research Institite, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Tanzania

114Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

115UMR-MD3, Faculty of Pharmacy, Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France

116Centre National de Recherche et de Formation sur le Paludisme (CNRFP), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

117Department of Clinical Research, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

118Médecins Sans Frontières, London, UK

119WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN)-East Africa Regional Centre, Nairobi, Kenya

120University of Oxford/KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Nairobi, Kenya

121Service de Médecine Internationale et Humanitaire, Hopitaux Universitaries de Genève, Geneva, Switzerland

122University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

123Sigma-Tau Industrie Farmaceutiche Riunite S.p.A, Rome, Italy

124Malariology department, Institut Pasteur de Côte d'Ivoire, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

125Methodology and Statistical Unit, Center for Health Studies, CRP Santé, Luxemburg, Luxemburg

126Unité 3677, Bases thérapeutiques des inflammations et infections, Université Victor Segalen Bordeaux 2, Bordeaux, France

127Centre for Infectious Disease Control, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands

128Division of Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Medicine and Travel Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

129Department of Parasitology, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK

130Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

131Department of Parasitology and Mycology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences, University of Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

132Malaria Research and Control Center, National Institute of Public Health, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

More information about the authors can be found in (Additional file 5).

Funding

WWARN is funded by a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant. The funder did not participate in the study protocol development or the writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Additional information

Competing interests

Stephan Duparc is an employee of Medicines for Malaria Venture, Geneva, Switzerland; Kamal Hamed is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA; Valerie Lameyre and François Bompart are employees of Sanofi, Paris, France; and Silva Tommasini and Giovanni Valentini are employees of Sigma-Tau Industrie Farmaceutiche Riunite, Rome, Italy. Piero Olliaro co-initiated and Jean René Kiechel managed the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative FACT project, which developed fixed dose artesunate-amodiaquine. Umberto D’Alessandro has received research funding and travel grants from Sanofi, Novartis and Sigma Tau, and has been a consultant for Sigma Tau on dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Quique Bassat has received speaker fees and travel grants from Sigma Tau. Elizabeth A Ashley has worked as an investigator on studies of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine sponsored by both Holley-Cotec, Beijing, China, and Medicines for Malaria Venture, and has received research funding from Holley-Cotec. Ric N Price served on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for the Sigma Tau DP multicenter clinical trials and received reimbursements for travel expenses to attend these meetings. Karen I Barnes is a recipient of a research grant from the Medicines for Malaria Venture and is a sub-recipient of grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Karen I Barnes is a member of the WHO Technical Expert Group on Malaria Chemotherapy and Drug Resistance and Containment. Piero Olliaro is a staff member of the WHO. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the WHO. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

SA, IA, GOA, MAA, BHA, RA, EA, EAA, MSB, Hbarennes, KIB, QB, EB, NBR, AB, FB, MB, SB, TB, PB, HBukirwa, FC, UDA, MD, AD, AAD, GD, OKD, CJD, SD, TE, EE, JFE, AMF, COF, CIF, JFF, BFaye, OF, SF, BFofana, CF, NBG, OG, BGenton, JPGil, RG, FG, BGreenhouse, BGreenwood, AG, PJG, JPGuthman, KH, SH, EMH, JH, MLI, DJ, JJJ, VJ, EJ, PSK, PAK, EK, MRK, CK, KK, JRK, FK, PEK, PGK, SK, VL, BL, AL, MMakanga, EMM, KM, AMartensson, AMassougbodji, HM, DM, CMenendez, PFM, MMeremikwu, CNabasumba, MN, JLN, BEN, FNikiema, FNtoumi, MO, BRO, PO, SAO, JBO, SOA, LKP, MP, JP, LP, PP, CVP, ZP, RNP, MR, LR, CR, PJR, IS, ASE, PS, HDFHS, BS, SAS, CHS, VS, SBS, FAS, DS, SGS, CJS, TDS, KSylla, AOT, WRJT, EAT, JIT, RCKT, HT, ST, OAT, JU, MTV, GV, IVDB, MVV, SAW, PAW, WY, AY, YMZ and IZ conceived and designed the experiments. SA, IA, GOA, MAA, BHA, RA, EA, EAA, MSB, Hbarennes, KIB, QB, EB, NBR, AB, FB, MB, SB, TB, PB, HBukirwa, FC, UDA, MD, AD, AAD, GD, OKD, CJD, SD, TE, EE, JFE, AMF, COF, CIF, JFF, BFaye, OF, SF, BFofana, CF, NBG, OG, BGenton, JPGil, RG, FG, BGreenhouse, BGreenwood, AG, PJG, JPGuthman, KH, SH, EMH, JH, MLI, DJ, JJJ, VJ, EJ, PSK, PAK, EK, MRK, CK, KK, JRK, FK, PEK, PGK, SK, VL, BL, AL, MMakanga, EMM, KM, AMartensson, AMassougbodji, HM, DM, CMenendez, PFM, MMeremikwu, CNabasumba, MN, JLN, BEN, FNikiema, FNtoumi, MO, BRO, PO, SAO, JBO, SOA, LKP, MP, JP, LP, PP, CVP, ZP, MR, LR, CR, PJR, IS, ASE, PS, HDFHS, BS, SAS, VS, SBS, FAS, DS, SGS, CJS, TDS, KSylla, AOT, WRJT, EAT, JIT, RCKT, HT, ST, OAT, JU, MTV, GV, IVDB, MVV, SAW, PAW, WY, AY, YMZ and IZ enrolled patients. PD, PJG, CMoreira, CNsanzabana, RNP, CHS and KStepniewska analyzed the pooled individual patient data. PD and KStepniewska performed the statistical analysis. JAF, PWG, SIH and GSH contributed to the analysis. AS contributed to the collection of the different datasets. CNsanzabana performed the literature search. PJG identified the relevant studies to be included in the analysis. PD, UDA, GD, PJG, CNsanzabana, RNP, CHS and AOT wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and participated in subsequent editing and final submission and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

References of all clinical trials and their study designs. (XLSX 1094 kb)

Additional file 2:

Maps showing locations of published clinical efficacy studies and the studies included in the pooled analysis. (PDF 173 kb)

Additional file 3:

Transmission classification. (XLSX 29 kb)

Additional file 4:

Additional tables and figures. (DOCX 379 kb)

Additional file 5:

Authors and contributions. (XLS 82 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

WWARN Artemisinin based Combination Therapy (ACT) Africa Baseline Study Group. Clinical determinants of early parasitological response to ACTs in African patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria: a literature review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMC Med 13, 212 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0445-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0445-x