Abstract

Background

Alcohol consumption patterns change across life and this is not fully captured in cross-sectional series data. Analysis of longitudinal data, with repeat alcohol measures, is necessary to reveal changes within the same individuals as they age. Such data are scarce and few studies are able to capture multiple decades of the life course. Therefore, we examined alcohol consumption trajectories, reporting both average weekly volume and frequency, using data from cohorts with repeated measures that cover different and overlapping periods of life.

Methods

Data were from nine UK-based prospective cohorts with at least three repeated alcohol consumption measures on individuals (combined sample size of 59,397 with 174,666 alcohol observations), with data spanning from adolescence to very old age (90 years plus). Information on volume and frequency of drinking were harmonised across the cohorts. Predicted volume of alcohol by age was estimated using random effect multilevel models fitted to each cohort. Quadratic and cubic polynomial terms were used to describe non-linear age trajectories. Changes in drinking frequency by age were calculated from observed data within each cohort and then smoothed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. Models were fitted for men and women separately.

Results

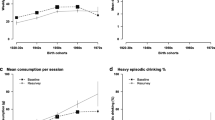

We found that, for men, mean consumption rose sharply during adolescence, peaked at around 25 years at 20 units per week, and then declined and plateaued during mid-life, before declining from around 60 years. A similar trajectory was seen for women, but with lower overall consumption (peak of around 7 to 8 units per week). Frequent drinking (daily or most days of the week) became more common during mid to older age, most notably among men, reaching above 50% of men.

Conclusions

This is the first attempt to synthesise longitudinal data on alcohol consumption from several overlapping cohorts to represent the entire life course and illustrates the importance of recognising that this behaviour is dynamic. The aetiological findings from epidemiological studies using just one exposure measure of alcohol, as is typically done, should be treated with caution. Having a better understanding of how drinking changes with age may help design intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol consumption and its associated harms are high on the public health agenda [1]. In the UK it is estimated that there were 8,367 alcohol-related deaths in 2012 [2] and that 8% of all hospital admissions involved an alcohol-related condition [3]. In order to identify high risk drinkers and plan for resource allocation, an accurate estimate of exposure to alcohol in the population is needed. In addition to sales data from industry sectors [4], estimates are typically drawn from cross-sectional population surveys such as, for example, the General Lifestyle Survey [5], the Health Survey for England [6], and the Scottish Health Survey [7]. Such surveys can help identify high risk groups in society [8], describe trends over time [9,10], and predict the associated burden of harm and costs [11].

Population cross-sectional surveys can also be used to compare consumption across age-groups [12]. However, cross-sectional surveys are limited as they are fixed in one specific historical moment. Alcohol consumption levels fluctuate across life [13,14] and only analysis of longitudinal data, with repeat alcohol measures, is able to reveal changes in consumption within the same individuals as they age [15]. Estimating alcohol consumption trajectories as people age and mature through the life course can ultimately be used to identify associated harm [16,17]. This allows for the investigation of whether there are sensitive periods during life when certain patterns of alcohol consumption are more harmful, and whether the impact of drinking accumulates over time [18]. Such information can be used to inform public health initiatives and sensible drinking advice.

Unfortunately, there is a paucity of datasets that are able to describe individual trajectories over the whole life course, with most focussing on adolescence to early adulthood [19-23] or mid-life into older age [24-29]. Previous attempts to synthesise data from several cohorts [30,31] in order to map across all ages are hampered by the inclusion of studies with only two time-point measurements of alcohol; this is not considered sufficient to examine trajectories [32] and may give rise to statistical issues such as regression to the mean [33]. An alternative to examining life course trajectories in a single cohort and an improvement over sequential cross-sectional analyses, is to compare data from multiple cohorts with repeated measurement that cover different and overlapping periods of life [34], as has been undertaken to examine blood pressure trajectories [35].

In this paper, we explore the extent to which alcohol consumption (mean weekly volume and drinking frequency) changes over the life course using data from nine UK-based cohorts with at least three repeated measures on individuals, with data spanning from adolescence to very old age (90 years plus). To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to synthesise information from overlapping large population-based cohorts to represent alcohol consumption across the entire life course.

Methods

Study populations

All cohorts included in these analyses have at least three repeat measures of alcohol consumption (volume and frequency) and are based in the UK (Table 1). Three are nationally representative birth cohorts: the Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD; 1946 British Birth Cohort) [36,37], the National Child Development Survey (NCDS; 1958 British Birth Cohort) [38], and the 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70) [39]. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) is a representative cohort of older people in England [40]. The Whitehall II study is a prospective cohort study of civil servants aged 35 to 55 years (at baseline) working in London [41]. Three cohorts are representative population samples from the West of Scotland (Twenty-07 study; T-07) [42]. These three cohorts are born 20 years apart (1930s, 1950s, and 1970s) with data collected from ages 15 to 37, 35 to 56, and 55 to 76 years. The Caerphilly Prospective Cohort Study (CaPS) is based on a population-based sample of men aged 45 to 59 years in South Wales [43].

The cohorts contributed data from early life (age 15 years in T-07 1970s cohort) up to age 90 years and older (ELSA), with cohorts overlapping to some extent across different periods of life. Most of the data collection phases were from the mid-1980s onwards (Table 1). The combined sample size was 59,397 individuals (54% men) with 174,666 alcohol observations.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was given by the Central Manchester Research Ethics Committee (REC) for the latest NSHD data collection, which took place in England and Wales (07/H1008/245), and by the Scotland A REC. Each wave of the West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study was approved by the local NHS or University of Glasgow ethics committees. The University College London Medical School Committee on the ethics of human research approved the Whitehall II study. The CaPS study was reviewed by several different RECs over the past three decades, including South Glamorgan Area Health Authority, Gwent REC, and South East Wales REC. Ethical approval for ELSA and NCDS was granted by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee. Written and informed consent was obtained for every participant.

Alcohol consumption

Mean weekly alcohol consumption was derived from each cohort and harmonised to UK units (where 1 unit equals 8 g ethanol [44]). Likewise, frequency of consumption was derived in each cohort and grouped as: “none in past year”, “monthly/special occasions”, “weekly infrequent”, and “weekly frequent” (daily or almost daily). Further details are available in Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

Predicted volume of alcohol consumed as a function of age was estimated using random effect multilevel models fitted to each cohort. In studies where age was consistent across individuals (birth cohorts), linear effects were assumed when only three measurement occasions were available (e.g., BCS70) while in studies with four or more measures, or a range of ages at each occasion, quadratic and cubic polynomial terms were used to describe non-linear trajectories. Covariance between the random coefficients was allowed. Models were fitted for men and women separately and estimated using a maximum likelihood algorithm. Model fit was evaluated using likelihood tests and examining changes in the Bayesian information criterion. Robust standard errors were calculated for the best fitting model. Changes in drinking frequency by age were calculated from observed data within each cohort and represented in terms of the mean percentage of individuals reporting a particular category of consumption at any given age. These observed trajectories were then smoothed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing.

We then combined all cohorts into a single dataset and fitted a three-level multilevel model (observations nested within individuals nested in individual cohorts) to estimate volume of alcohol consumed as a function of age across the life course with adjustment for period (broadly defined using the decade in which the measurements took place). We used fractional polynomial terms [45,46] to best describe the shape of the trajectory and centred age at 40 years. We also included an interaction between age and period to examine potential differences in alcohol intake across the life course at different time periods (available in Additional file 2).

All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 [47]. As a form of sensitivity analysis we compared the estimates obtained from these models to those calculated among complete cases only and found a consistent pattern of results (available upon request) suggesting that our findings are unlikely to be biased under the assumption of missing at random.

Results

Among men, mean consumption rose sharply during adolescence, peaked at around age 25 years at 20 units per week, and then declined and plateaued during mid-life, before declining from around 60 years to 5 to 10 units per week (Figure 1). Similar mean trajectories were seen for women, but with lower overall consumption (peak of around 7 to 8 units per week falling to 2 to 4 units in those aged 70 and above; Figure 2). The coefficients for the age effects from these models are shown in Table 2. The steepest rise in alcohol volume was found in the Twenty-07 1970s young male adolescent cohort, where increases in three and a half units per year (standard error, 0.63) were found between ages 15 and about 25 years. The steepest decline was found among ELSA men where decreases in almost one unit per year (regression coefficient, −0.90; standard error, 0.07) were found from 45 years.

The combined predicted mean consumption trajectories for men and women are shown in Figure 3. These show the sharp increase in volume during adolescence followed by a gradual decline as people age.

Non-drinkers were uncommon, particularly among men, where the proportion remained under 10% until old age, when it rose to above 20% among those aged over 90 (Figure 4). Drinking once or twice a week was prevalent among adolescents and those in their twenties. Drinking only monthly or on special occasions was more common among women than men (Figure 5). Frequent drinking (daily or most days of the week) became more common in middle to old age, most notably among men, reaching above 50% in men aged 65 years and over in the Whitehall II cohort. Frequent drinking declined in very old age.

Each cohort was overlapped to some extent by at least one other cohort with data at a similar age. Whilst the volume trajectories were broadly similar across cohorts at the same age points, there were some notable differences. For example, mean consumption was lower among men in the Whitehall II cohort and higher in the CaPs and ELSA cohorts at around ages 45 to 50 years. Older women in the West of Scotland cohort (T-07 1930s) reported much lower consumption than women of a similar age in the Whitehall II cohort. These data were collected at similar times (2002 onwards) so are unlikely to reflect period effects.

There were slight differences in rate of change in alcohol consumption across the life course by period; however, the overall shape of the trajectory remained the same (a peak in early adulthood followed by a decline from midlife onwards; Additional file 2).

Discussion

This is the first attempt to synthesise and harmonise information on alcohol consumption from overlapping cohorts to represent the whole life course, using data from large population based cohorts of men and women, with multiple repeated measures of consumption as they age. Our analyses describing the average volume of alcohol consumed showed a rapid increase in consumption during adolescence, followed by a plateau in mid-life, and then a decline into older ages. Drinking occasions, on the other hand, tended to become more frequent with daily/nearly daily consumption being most common in older men, suggesting a shift away from irregular drinking in earlier years. This latter finding supports concerns raised recently about the misuse of alcohol among older people [48].

The trajectories are based on over 174,000 alcohol observations. With a minimum of three repeated measurements from each cohort, we were able to model non-linear effects. This was a serious limitation of previous work [30,31]. Great care was taken to harmonise the information on volume and frequency despite it being gathered using different questionnaires; however, we were not able with these datasets to capture full details of drinking pattern or context of drinking occasions over time. The volume and frequency estimates were reliant upon self-report, which may lead to both over- and under-estimation [49] and the strength of some alcohol consumed is likely to have increased over time [12]. Estimates of population level alcohol consumption from surveys are lower than sales data suggest, largely due to their failure to capture heavy drinking sections of society [50,51]. Furthermore, longitudinal population cohort studies are at risk of selective attrition, which may mean that heavier drinkers were more likely to drop out [52]. However, our sensitivity analyses showed that selective attrition did not seem to affect the main results.

Our findings are broadly in agreement with individual studies on drinking behaviour change which report that alcohol consumption decreases with age [13,14,24,30], with some suggesting that drinking patterns stabilise around the age of 30 [31] and in middle age [29], whilst others suggest later at age 50 years [25]. Fillmore et al. [30] combined data from 20 longitudinal studies from Europe, US, and New Zealand to look at changes in quantity of drinking and found that mean consumption declined significantly with age in men until they reached their seventies, whilst mean consumption in women decreased slightly at ages 15 to 29 and 40 to 49 years [30]. In an updated meta-analysis of these studies, Johnstone et al. [31] evaluated drinking frequency and found settled patterns after the age of 30 years following earlier marked variation. In these meta-analyses, change in consumption was assessed using only two measurements of alcohol and, therefore, the authors were unable to estimate trajectories of change with growth curve or other dynamic modelling procedures.

The data presented in this paper were collected over a 34 year period (1979 to 2013) and the participants were born in different eras (spanning 1918 to 1973), therefore, the interpretation needs to be set against period and cohort effects [53]. To a certain extent, we were able to look at period effects by examining data collected in three different decades and found only minor differences. Furthermore, this is corroborated with data from the World Health Organisation, which suggest there have been only minor differences in the estimates of alcohol per capita over the last two decades [54]. On the other hand, the overlapping cohorts provide an opportunity to compare the robustness and time-resistant nature of the trajectories. Clearly, there are some cohort differences, which are likely to be partly attributable to covariates such as socio-economic position. The lower estimates of male alcohol consumption in the Whitehall II cohort are likely due to it being a ‘white collar’ occupational cohort compared to the other population-based cohorts. We chose not to adjust for covariates, but to present the actual trajectories for each cohort separately and combined.

Reassuringly, the estimates from the nine UK cohorts of around 15 to 20 units per week for adult men are similar to the estimates obtained in the General Lifestyle Survey (GLS), which covers Great Britain (mean of 17.8 units for men aged 45 to 64 years, 2010) [55]. The female cohort estimates of 4 to 6 units are slightly lower than the GLS estimates (approximately 8 units per week across adulthood). The GLS data also suggests declines in older age groups with lower average consumption among people aged 65 and over (12.5 units for men and 4.6 for women). However, the GLS cross-sectional data is fixed at one point in time (2010 in the case here) and should not be used alone to describe age-related alcohol trajectories.

In this paper, we focused on mean trajectories of consumption, which, by necessity, masks the individual variations. Future work will classify trajectories of lifetime drinking according to profiles (for example, persistent heavy drinker, increasing drinker, sporadic drinker, etc.) using growth mixture modelling or latent class analysis [19,56,57] and, where available, the identified trajectory profiles will be analysed in relation to outcome data such as mortality and incidence of cardiovascular disease and cancer. This will allow for the investigation of whether there are sensitive periods during life when certain patterns of alcohol consumption are more harmful and whether the impact of drinking accumulates over time [58]. Such information can be used to inform public health initiatives and sensible drinking advice.

Capturing variations in drinking pattern over time has been the focus of scientific endeavour for decades [13] and it has long been known that alcohol consumption may fluctuate over the life course. However, much of the evidence linking alcohol to health outcomes relies upon evidence from prospective cohort studies in which exposure to alcohol is measured only once at baseline. It is assumed that this initial consumption level is an accurate measure of exposure throughout the study period (which may be several decades for some health outcomes). Epidemiological studies using just one exposure measure of alcohol, as is typically done, should be treated with caution. The current evidence base lacks this consideration of the complexity of lifetime consumption patterns, as well as the major predictors of change in drinking and the subsequent health risks. Research on the health consequences of alcohol needs to address the effects of changes in drinking behaviour over the life course [59].

Conclusions

This is the first attempt to synthesise longitudinal data on alcohol consumption from several overlapping cohorts to represent the entire life course. We found that consuming alcohol is common at all ages in the UK and that individuals change their drinking pattern substantially as they age; initial increases in volume during adolescence are followed by a more stable period during mid-life before declines in volume into older age. The frequency of intake shifts from less frequent occasions to a daily/nearly daily intake being most common among elderly men.

Abbreviations

- BCS70:

-

1970 British Birth Cohort

- CaPS:

-

Caerphilly Prospective Cohort Study

- ELSA:

-

English Longitudinal Study of Ageing

- GLS:

-

General Lifestyle Survey

- NCDS:

-

National Child Development Survey

- NSHD:

-

National Survey of Health and Development

- REC:

-

Research Ethics Committee

- T-07:

-

Twenty-07 Study

References

Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365:519–30.

Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-related deaths in the United Kingdom, registered in 2012. London: ONS; 2014.

Office for National Statistics. Drinking habits amongst adults, 2012. London: ONS; 2013.

Beer B, Association P. Statistical handbook 2009. London: Brewing Publications Limited; 2012.

Robinson S, Bugler C. General lifestyle survey 2008. Smoking and drinking among adults, 2008. London: ONS; 2010.

Mindell J, Biddulph JP, Hirani V, Stamatakis E, Craig R, Nunn S, et al. Cohort profile: the health survey for England. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1585–93.

Gray L, Batty GD, Craig P, Stewart C, Whyte B, Finlayson A, et al. Cohort Profile: The Scottish Health Surveys Cohort: linkage of study participants to routinely collected records for mortality, hospital discharge, cancer and offspring birth characteristics in three nationwide studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:345–50.

Knott CS, Scholes S, Shelton NJ. Could more than three million older people in England be at risk of alcohol-related harm? A cross-sectional analysis of proposed age-specific drinking limits. Age Ageing. 2013;42:598–603.

Twigg L, Moon G. The spatial and temporal development of binge drinking in England 2001–2009: an observational study. Soc Sci Med. 2013;91:162–7.

Smith L, Foxcroft DR. Drinking in the UK: an exploration of trends. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2009.

Britton A, McPherson K. Mortality in England and Wales attributable to current alcohol consumption. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:383–8.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Statistics on alcohol: England, 2013. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2013.

Fillmore KM. Prevalence, incidence and chronicity of drinking patterns and problems among men as a function of age: a longitudinal and cohort analysis. Br J Addict. 1987;82:77–83.

Kerr WC, Fillmore KM, Bostrom A. Stability of alcohol consumption over time: evidence from three longitudinal surveys from the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2002;63:325.

Gilhooly ML. Reduced drinking with age: is it normal? Addict Res Theory. 2005;13:267–80.

Fan AZ, Russell M, Stranges S, Dorn J, Trevisan M. Association of lifetime alcohol drinking trajectories with cardiometabolic risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:154–61.

Berg N, Kiviruusu O, Karvonen S, Kestilä L, Lintonen T, Rahkonen O, et al. A 26-year follow-up study of heavy drinking trajectories from adolescence to mid-adulthood and adult disadvantage. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:452–7.

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:778–83.

Casswell S, Pledger M, Pratap S. Trajectories of drinking from 18 to 26 years: identification and prediction. Addiction. 2002;97:1427–37.

Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008;103:7–22.

Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103:84–99.

Degenhardt L, O’Loughlin C, Swift W, Romaniuk H, Carlin J, Coffey C, et al. The persistence of adolescent binge drinking into adulthood: findings from a 15-year prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003015.

Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Maggs JL, et al. Substance use changes and social role transitions: proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:917.

Moos RH, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, Moos BS. Older adults’ alcohol consumption and late‐life drinking problems: a 20‐year perspective. Addiction. 2009;104:1293–302.

Bobo JK, Greek AA, Klepinger DH, Herting JR. Alcohol use trajectories in two cohorts of US women aged 50 to 65 at baseline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2375–80.

Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos RH. Patterns and predictors of late-life drinking trajectories: a 10-year longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:254–64.

Bobo JK, Greek AA, Klepinger DH, Herting JR. Predicting 10-year alcohol use trajectories among men age 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:204–13.

Molander RC, Yonker JA, Krahn DD. Age-related changes in drinking patterns from mid- to older age: results from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1182–92.

Platt A, Sloan FA, Costanzo P. Alcohol-consumption trajectories and associated characteristics among adults older than age 50. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:169.

Fillmore KM, Hartka E, Johnstone BM, Leino EV, Motoyoshi M, Temple MT. A meta-analysis of life course variation in drinking. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1221–68.

Johnstone BM, Leino EV, Ager CR, Ferrer H, Fillmore KM. Determinants of life-course variation in the frequency of alcohol consumption: meta-analysis of studies from the collaborative alcohol-related longitudinal project. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1996;57:494.

Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–20.

Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age–period–cohort modelling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104:27–37.

Wills AK, Lawlor DA, Matthews FE, Sayer AA, Bakra E, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Life course trajectories of systolic blood pressure using longitudinal data from eight UK cohorts. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000440.

Wadsworth M, Kuh D, Richards M, Hardy R. Cohort profile: the 1946 National Birth Cohort (MRC National Survey of Health and Development). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:49–54.

Kuh D, Pierce M, Adams J, Deanfield J, Ekelund U, Friberg P, et al. Cohort profile: updating the cohort profile for the MRC National Survey of Health and Development: a new clinic-based data collection for ageing research. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:e1–9.

Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:34–41.

Elliott J, Shepherd P. Cohort profile: 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:836–43.

Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–8.

Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:251–6.

Benzeval M, Der G, Ellaway A, Hunt K, Sweeting H, West P, et al. Cohort profile: West of Scotland twenty-07 study: health in the community. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1215–23.

The Caerphilly and Speedwell Collaborative Group. Caerphilly and Speedwell collaborative heart disease studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 1979. 1984;38:259–62.

Department of Health, United Kingdom. Sensible drinking report of an inter-departmental working group. London: Department of Health; 1995.

Royston P, Ambler G, Sauerbrei W. The use of fractional polynomials to model continuous risk variables in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:964–74.

Royston P, Altman DG. Regression using fractional polynomials of continuous covariates: parsimonious parametric modelling. Appl Stat. 1994;43:429–67.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013.

Crome I, Brown A, Dar K, Harris L, Janikiewicz S. Our invisible addicts: first report of the Older Persons’ Substance Misuse Working Group of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2011.

Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity–frequency, graduated–frequency and recent recall. Addiction. 2004;99:1024–33.

Meier PS, Meng Y, Holmes J, Baumberg B, Purshouse R, Hill-McManus D, et al. Adjusting for unrecorded consumption in survey and per capita sales data: quantification of impact on gender- and age-specific alcohol-attributable fractions for oral and pharyngeal cancers in Great Britain. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:241–9.

Rehm J, Kehoe T, Gmel G, Stinson F, Grant B, Gmel G. Statistical modeling of volume of alcohol exposure for epidemiological studies of population health: the US example. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:3.

Grittner U, Gmel G, Ripatti S, Bloomfield K, Wicki M. Missing value imputation in longitudinal measures of alcohol consumption. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20:50–61.

Meng Y, Holmes J, Hill-McManus D, Brennan A, Meier PS. Trend analysis and modelling of gender-specific age, period and birth cohort effects on alcohol abstention and consumption level for drinkers in Great Britain using the General Lifestyle Survey 1984–2009. Addiction. 2014;109:206–15.

Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH). http://www.who.int/gho/alcohol/consumption_levels/en/.

Office for National Statistics. General lifestyle survey, 2010. London: ONS; 2012.

Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person‐centered and variable‐centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:882–91.

Oxford ML, Gilchrist LD, Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Lohr MJ, Lewis SM. Alcohol use among adolescent mothers: heterogeneity in growth curves, predictors, and outcomes of alcohol use over time. Prev Sci. 2003;4:15–26.

Mishra G, Nitsch D, Black S, De Stavola B, Kuh D, Hardy R. A structured approach to modelling the effects of binary exposure variables over the life course. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:528–37.

Greenfield TK, Kerr WC, Commentary on Liang & Chikritzhs (2011). Quantifying the impacts of health problems on drinking and subsequent morbidity and mortality – life-course measures are essential. Addiction. 2011;106:82–3.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants in the nine cohorts used in this study an also the research teams involved in collecting, preparing, and interpreting these data and entering them into electronic databases. We would also like to thank Professor Jane Elliot, Director of Institute of Education, University of London, for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Funding disclosure

AB and SB are funded by the European Research Council (309337, PI: Britton, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/alcohol-lifecourse). The Whitehall II study is supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (K013351), British Heart Foundation (RG/07/008/23674), Stroke Association, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL036310), and National Institute on Aging (AG13196 and AG034454). The NSHD and DK are supported by the Medical Research Council (MR_UC_12019/01). Twenty 07 is funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_A540_53462). The CaPS was funded by the MRC Epidemiology Unit (Cardiff).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB and SB conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. SB performed the statistical analyses. YB-S, MB, and DK provided data, participated in the design of the study, and contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Details on the harmonisation procedure for alcohol consumption data in the nine participating cohorts.

Additional file 2:

Additional analyses in the combined dataset testing for potential period effects.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Britton, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Benzeval, M. et al. Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Med 13, 47 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0273-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0273-z