Abstract

Background

Hearing loss can have a negative impact on individuals’ health and engagement with social activities. Integrated approaches that tackle barriers and social outcomes could mitigate some of these effects for cochlear implants (CI) users. This review aims to synthesise the evidence of the impact of a CI on adults’ health service utilisation and social outcomes.

Methods

Five databases (MEDLINE, Scopus, ERIC, CINAHL and PsychINFO) were searched from 1st January 2000 to 16 January 2023 and May 2023. Articles that reported on health service utilisation or social outcomes post-CI in adults aged ≥ 18 years were included. Health service utilisation includes hospital admissions, emergency department (ED) presentations, general practitioner (GP) visits, CI revision surgery and pharmaceutical use. Social outcomes include education, autonomy, social participation, training, disability, social housing, social welfare benefits, occupation, employment, income level, anxiety, depression, quality of life (QoL), communication and cognition. Searched articles were screened in two stages ̶̶̶ by going through the title and abstract then full text. Information extracted from the included studies was narratively synthesised.

Results

There were 44 studies included in this review, with 20 (45.5%) cohort studies, 18 (40.9%) cross-sectional and six (13.6%) qualitative studies. Nine studies (20.5%) reported on health service utilisation and 35 (79.5%) on social outcomes. Five out of nine studies showed benefits of CI in improving adults’ health service utilisation including reduced use of prescription medication, reduced number of surgical and audiological visits. Most of the studies 27 (77.1%) revealed improvements for at least one social outcome, such as work or employment 18 (85.7%), social participation 14 (93.3%), autonomy 8 (88.9%), education (all nine studies), perceived hearing disability (five out of six studies) and income (all three studies) post-CI. None of the included studies had a low risk of bias.

Conclusions

This review identified beneficial impacts of CI in improving adults’ health service utilisation and social outcomes. Improvement in hearing enhanced social interactions and working lives. There is a need for large scale, well-designed epidemiological studies examining health and social outcomes post-CI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hearing loss can have a negative impact on an adults’ health and social well-being. Globally, in 2019, an estimated 1.57 billion people had some form of hearing loss, and this figure is estimated to increase to 2.45 billion by the year 2050 [1]. Hearing loss can lead to more frequent use of inpatient or outpatient healthcare services [2, 3], increased fall risk in healthcare facilities [4] and other locations [5], poor communication with providers when using healthcare services [6] that can affect a health consumer’s satisfaction [7] with healthcare delivery and utilisation [8]. Hearing loss is also associated with negative social outcomes, such as reduced academic performance, lower chance of progressing to higher education or undertaking training [9,10,11], unemployment [10, 11], poor personal relationships [12], feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem [12, 13], social isolation and loneliness [14], and higher rates of depression and low QoL [15,16,17]. Integrated approaches that tackle barriers and social outcomes could mitigate some of these effects for both CI users and their health providers [18]. For example, strategies such as noise reduction approaches, and acting on hearing healthcare, are all likely to ameliorate some of the negative aspects of hearing loss [1, 3, 19].

Cochlear implantation is the surgical insertion of an electrode within the inner most part of the ear to transmit sounds from an externally worn device. Cochlear implants are suitable for individuals with a severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss, who do not benefit from standard hearing aids [20, 21]. A cochlear implanted device can improve a person’s ability to understand speech through providing improved access to speech sounds [22,23,24]. Compared to their preoperative hearing with the use of hearing aids, a majority of CI users demonstrate improvement in speech recognition [25, 26]; however, the magnitude of improvement varies considerably across individual CI users [27,28,29,30]. Factors contributing to this variation are unclear, but different studies have suggested that this could be influenced by: age at implantation, age at onset of hearing loss, duration of implant use (up to 1–2 years), duration and cause of hearing loss, placement of implant in the cochlea, integrity of the cochlear nerve, as well as learning ability of the individual living with hearing loss [27, 31, 32].

Several studies have measured hearing outcomes in CI users [25, 33,34,35]. However, the potential impact of CI on health service utilisation and social outcomes are less understood. To our knowledge, no review has been found that comprehensively synthesized impacts of CI on health service utilisation such as hospital admissions, ED presentations, GP visits and prescription medication use. In addition, there have been few scoping reviews that have examined social outcomes such as work, autonomy and participation post-CI [36]. This review offers some important insights into improve service delivery, health service use and social outcome trajectories of the CI users. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesise the evidence of the impact of CI on health service utilisation and social outcomes in adult CI users.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [37] and the protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023392131). This review included studies reporting on health service utilisation or social outcomes of adults aged ≥ 18 years with considerable hearing loss who received a CI. The comparison was performed either between CI users and non-users with hearing loss but not implanted or within CI users, based on their pre- and post-operative outcomes. Hearing loss was defined according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition into moderate: 41 to 60 dB, severe: 61 to 80 dB, profound or complete deafness: ≥ 81 dB [38, 39]. CI users could be fitted either unilaterally, bilaterally, bimodally (using a hearing aid on the other ear) or by electric-acoustic stimulation (only part of the cochlea is stimulated with a cochlear implant). Articles were excluded if they solely reported on children or individuals with prelingual hearing loss and did not separately report results for adults. Articles were excluded if they were reviews, editorials or opinion pieces, single case report, study protocols, or conference abstracts. This review included English-language articles that were published in a peer-review journal.

The main outcomes of interest are health service utilisation (e.g., hospital admissions, ED presentations, GP visits, CI revision surgery and pharmaceutical use); and social outcomes (e.g., circumstances relating to education, autonomy, social participation, training, disability, social housing, social welfare benefits, occupation, employment, income level, anxiety, depression, QoL, communication abilities and cognition).

Health service utilisation or social outcomes could either be in the short (e.g., < 6 months), medium (e.g., 6–12 months), or long-term (e.g., > 12 months). Health service utilisation included hospital admissions, ED presentations, GP visits, and prescription medication use. Social outcomes included information or circumstances relating to education, autonomy, social participation, training, disability, social welfare (e.g., social housing, welfare benefits), occupation, employment, or income level. Autonomy or independence was defined as the capability of living the way an individual wished to without being reliant on a third person to control, cope and make personal decisions on their life [36, 40]. Whereas the capability of participating in different social situations or activities without limitation due to hearing loss was defined as social participation [36, 41].

Study selection process

Five databases were searched, including MEDLINE and PsycINFO using the Ovid portal, Scopus, CINAHL using the EBSCOhost portal, and ERIC using the ProQuest portal. The search was conducted from 1 January 2000 to 16 January 2023 for the four common databases. On the recommendation of an educational expert, we added a search of the ERIC database in May 2023. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a university librarian. The full search strategy is provided (see Additional file 1). Snowballing of reference lists from the articles was conducted to identify any potential articles not previously identified. Title and abstract screening involved importing the title, abstract and citation information for each article identified during the database searching into EndNote X20. Duplicates were removed using EndNote. Following duplicate removal, the titles and abstracts of identified articles were screened and assessed for inclusion. Abstracts were excluded if they did not report on health service utilisation or social outcomes post-CI in adults. Uncertainties regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles based on title and abstract were discussed and consensus was obtained. Full-text screening was done by assessing each article against inclusion criteria. Following the full-text screening, a data extraction form was created and tested on five studies.

Data extraction

For studies that met the inclusion criteria, key characteristics of each study were extracted, including: authors and publication year; study objective or aim; study type; country/study setting and data collection timeframe; study population (e.g., mean age, sex, and sample size); information on health service utilisation and social outcomes. Data extraction was initially performed by one reviewer and subsequently verified for accuracy by two reviewers and any disagreements were discussed between reviewers and consensus was obtained.

Data synthesis

Information extracted from the included studies was narratively synthesised by one reviewer and appraised by two reviewers. The narrative synthesis involved tabulating and summarising health service utilisation and social outcomes.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of articles was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) cohort [42] or qualitative [43] study checklists as applicable. Quality assessment was initially performed by one reviewer and independently verified by two reviewers. Any disagreement regarding methodological quality were discussed between reviewers. The checklist consists of 12 questions for cohort, 10 questions for each cross-sectional and qualitative studies. Responses were recorded for each question based on the level of adequate information provided at design and analysis stages in the study. For example, “Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias?” ‘Yes’ was recorded for adequate information by looking for measurement or classification bias such as the use of subjective or objective measurements, do the measurement accurately measured what they intend to measure (validated vs. unvalidated tools), reliable method for detecting all cases, similarity of measurement methods in different groups and blinding of outcome assessor or subjects to exposure. Whereas ‘No’ was recorded for missing of one or more information and ‘Can’t tell’ was recorded if the information sought is not applicable. The overall quality of studies was judged based on ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ response to questions regarding relevance, reliability, validity and applicability.

Results

Description of studies

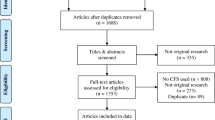

The search identified 2093 articles through searching of electronic databases and snowballing search methods. There were 2058 articles identified via the five databases, 541 were removed as duplicates. 1517 articles underwent title and abstract screening. Based on titles and abstracts, 1424 articles were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full text of the remaining 93 articles were assessed for eligibility. Following full text review, 49 articles were excluded due to an irrelevant target population or absence of the primary outcomes. The remaining 44 articles were intensively appraised and met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

There were 20 (45.5%) cohort studies (11 prospective and 9 retrospective), 18 (40.9%) cross-sectional studies and six (13.6%) qualitative studies. Almost all (93.2%, n = 41) of the included studies were conducted in high-income countries. Nine (20.5%) studies were conducted in United States of America (USA), six (13.6%) conducted in New Zealand, four (9.1%) conducted in Canada, three (6.8%) studies each were conducted in Germany and Norway, two (4.5%) studies each were conducted in Australia, Belgium, China, Finland, France, Norway and Poland and one study each was conducted in Brazil, Denmark, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Scotland, Sweden and the United Kingdom (UK). The sample size ranged from 125 to 5,130 participants for health service utilisation and 6 to 637 participants for social outcomes.

All studies included adults with severe to profound post-lingual hearing loss. Three studies [44,45,46] also included a few participants with prelingual hearing loss but were predominantly focussed on post-lingual hearing loss. Participants implanted with unilateral, bilateral, or bimodal CI were assessed within all studies. The mean duration of hearing loss was not often recorded in the included studies. Where reported (n = 11), the mean duration ranged from 2.5 to 32.7 years. The mean duration of follow-up from the date of CI ranged from 3 months to 23 years. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 101 years at the time of the study. However, one study had one CI user aged 17 years and thus was included in the sample [47]. The mean age of participants was not recorded in nine studies (20.5%), but where recorded, ranged from 21.9 to 80.9 years. Studies assessed outcomes by comparing CI users and non-users with hearing loss but not implanted (18.2%, n = 8) or within CI users, based on their pre- and post-operative outcomes (81.8%, n = 36).

Health service utilisation

Nine studies (20.5%) reported on health service utilisation (Table 1). Type of health service utilisation examined in each study varied and included readmission for CI revision (n = 5), post-operative surgical and audiological visits (n = 3), pneumococcal vaccination uptake (n = 1), extended hospital length of stay (n = 1), non-home destinations post-CI surgery (n = 1), and medication use (n = 1) (Table 2). The rate of CI revision surgery (with or without reimplantation) ranged from 1.1 to 3.8%. The average time from first implant to revision surgery ranged from 29 months to 7.8 years. Almost all studies indicated an ongoing need for CI revision surgery by users who had experienced complications post-CI. Where complications were reported, soft or hard device failure (n = 5) and flap skin infection, surgical or falls (n = 4) were the main reasons for the revision surgery. The mean number of health service visits ranged from 1.9 to 4.3 times a year. For example, one study [48] compared the health service visits of older (≥ 80 years) and younger adults (aged 60–79 years) within the CI group and found no difference in number of visits between the age groups, with the average number of visits decreasing for both age groups in the second year of post-operative follow-up. Pneumococcal vaccination uptake increased in CI users after a follow-up reminder in another study [49]. The study that examined medication use, identified that prescribed medication was used on average for 1.8 illnesses among CI users and for 3.1 illnesses in a non-user group [50].

Social outcomes

Thirty-five (79.5%) studies reported on social outcomes, 14 (40.0%) were cohort, 15 (42.9%) were cross-sectional and six (17.1%) were qualitative studies. The majority (71.4%, n = 25) of these studies reported social outcomes as a primary objective of the study (Table 3). Of the 35 studies, 21 (60.0%) reported on work or employment, 15 (42.9%) on social participation, nine (25.7%) on autonomy or independence, eight (22.9%) on education, six (17.1%) on perceived hearing disability, three (8.6%) on income, and two (5.7%) on safety and welfare.

Of the 21 studies that reported on work or employment, the majority (85.7%, n = 18) of studies found positive improvements on work or employment status post-CI. However, three studies (14.3%) did not find an additional benefit of CI on work or employment status. For example, one study conducted by Ross and Lyon [45], found CI users experienced difficulties in their workplace as employer expectations of hearing improvement post-CI were unrealistic.

Of the 15 studies that reported on social participation, improvement in social participation was observed in 14 (93.3%) studies post-CI. Only one study found no additional benefits in social participation post-CI [51]. The Chapman et al. 2017 [51] found that the CI cohort showed increased feelings of being limited due to their hearing loss, and that they participated less in mainstream organisational activities than the non-CI group. However, after categorising age into ≤ 25 and > 25 years, the authors found no statistical difference by age in participation in mainstream organisational activities. Also, the CI users in the older age group were found to socialise more with their hearing friends compared with non-users.

Independence or autonomy was reported in nine studies. Eight (88.9%) studies found substantial improvement in independence or autonomy following a CI. Only one study found no improvement in independence or autonomy measured by a subscale of quality of life [52]. Of the studies that found improvements in autonomy post-CI, Sonnet et al. 2017 [53], found improvement at 12-months post-CI. While another study [54] found a significant difference between pre- and post-implantation on autonomy at 6 months post-implantation, but this result did not persist at the 12-month follow-up.

Education or training was measured in nine studies. All studies that measured education or training found benefits post-CI. For example, Goh et al. 2016, found that 76% of CI users reported that the CI enabled them to access learning opportunities and gain tertiary qualifications [44]. Another study found that CI helped adults in retaining and developing professional abilities, for example two CI users were promoted to management positions and two moved to jobs requiring a higher level of skills [55].

Six studies measured perceived hearing disability. Five of the six studies found some improvements among respondents post-CI. For instance, one qualitative study [56] indicated participants perceived that the CI provided them a ‘new life’. CI was found to be associated with type of identity, such as deaf or hearing identity, type and quality of friendships, social activities, and feelings of limitation previously attributed to hearing loss [51].

Three studies reported on income and two on safety and welfare benefits. The three studies that reported on income, all found increases in the recipient’s income level post-CI. For example, one study [57] found a 31% increase in income bracket after a mean 6.6 years post-CI. Montero and colleagues [58] also found a significant increase in median annual income post-CI compared with preimplantation (CAD $42,672 vs. CAD $30,432). However, none of the identified studies found a positive change in welfare benefits. For instance, Mo et al. 2004 found no significant difference between CI and non-CI users in terms of safety, and welfare [59]. Again, the authors found that after 12 and 15 months post-CI, welfare and safety were not significantly improved [60].

Communication, anxiety, depression, quality of life and cognition

Of the 35 studies that reported on societal outcomes, ability to communicate was reported in 27 (77.1%), QoL in 15 (42.9%), and six (17.1%) studies each reported anxiety or depression and cognition. Of the studies that reported on communication abilities and QoL, all found improvement post-CI. Four of the six studies that reported on anxiety or depression found a reduced level of anxiety or depression post-CI. For example, Mo et al. 2005 [60] found the reduced mean score of anxiety and depression between pre- and post-implantation (-0.10 vs. -0.19). While two of the six studies found no change for anxiety or depression post-CI [53, 61]. There were mixed results on the effects of CI on anxiety, depression and cognitive function over time. For instance, Claes et al. 2018 found a decreased level of anxiety and depression at six months post-CI, however, the decrease was not sustained at a 12 month follow-up [62]. In contrast, another study found a decreased level of anxiety and depression after 12 months and 15 months post-CI [60] that was associated with gain in QoL. On the other hand, in the remaining study at 6 and 12 months post-CI, anxiety, depression levels and cognitive function remained stable [53].

Quality assessment

The overall quality of included studies was deemed low. None of the included studies had a low risk of bias due to inadequate methods to minimise the effects of confounding factors at design and analysis stage as defined by the CASP criteria. Few studies (36.4%, n = 16) scored ‘Yes’ for questions related to minimising the effects of confounding factors (see Additional file 2).

Discussion

This systematic review has synthesised evidence found in 44 studies regarding health service utilisation and social outcomes in adult CI users. The review identified limited research on health service utilisation post-CI. A systematic review that incorporated quantitative pooling of prospective studies to produce overall effect size is imperative. Despite a small number of studies examined health service utilisation, more than half found benefits of a CI. Most included studies (77.1%) have reported improvements for at least one social outcome post-CI.

Relatively small number of CI users who experienced complications required CI revision surgery. The review found that device failure (soft and hard) and medical-related predominantly skin flap-related infections were common reasons for the revision surgery. The current finding supports the need to maintain long-term follow-up post-CI to identify and manage any potential complications. Also, this study supports the importance of counselling for users about realistic expectations post-CI surgery. Prior research recommends that CI users receive a lifetime follow-up to identify and monitor any long-term complications [63, 64].

The current review found that CI users took prescribed medications for a lower number of illnesses than individuals on a wait list for a CI [50]. Similarly, prior studies have indicated that wearing hearing aids or cochlear implants improved communication abilities that further translated into improved health conditions and reduced unnecessary self-medication [19, 65]. However, it has been shown that waiting for medical intervention increases anxiety, depression and may reduce QoL [66]. As such, an individual’s position on a waiting list for CI may lead to negative emotions and associated physiological responses [50].

The current review found substantial improvement in work or employment status post-CI. These findings are consistent with a prior review that indicated evidence of improvement in work performance and employment status post-CI [36]. Only a few studies did not find an additional benefit of CI on work or employment. For instance, CI users reported challenges in their workplace because employers expected that CI can fully restore their normal hearing [45]. Further research that examines employers’ knowledge and expectations post-CI in the workplace may be of benefit.

Improvements were observed in social participation and in autonomy in almost all studies post-CI. Cochlea implant was associated with improved quality of life and speech perception which led to a demonstrated improvement in social participation [54, 67, 68]. CI was also found to improve independence in the adult population. Improvements in QoL may primarily be responsible for the increased feelings of autonomy or independence [69]. Similarly, a scoping review that examined the effects of CI on autonomy, participation and work found similar improvements post-CI [36]. The current review identified inconsistent definitions for both social participation and autonomy as well as inconsistency in the tools used to assess these constructs across studies. Within the included studies, there was an overlap between the examination of social participation and interrelated definitions, such as self-esteem, independence, activity limitations or QoL. Likewise, there were differences in the measurement of autonomy or independence across studies. Although the current review was inclusive of all definitions, further research is suggested to develop validated definitions for social participation and for autonomy or independence for CI users.

All studies that measured effects of CI on education or training found benefits post-CI. Compared with the general population, young adult CI users had a higher rate of attendance at post-secondary education programs and also reported being able to achieve their academic and personal goals [70]. Similarly, a review of five randomised controlled trials in adults who had received a hearing aid found that hearing aids were viewed as having improved educational opportunities [71].

Three studies reported on a CI recipient’s income [57, 58, 72] and all found a higher income level post-CI. However, none of the studies reporting on welfare found additional benefits post-CI. For example, Mo et al. 2004 compared CI with non-CI users and found no significant differences in terms of welfare or safety [59], even at 12 and 15 months post-CI [60]. Large scale and well-designed epidemiological studies are needed to examine the long-term association of CI on income or welfare benefits.

Studies that examined QoL found substantial improvement post-CI using different assessment tools [52,53,54, 59, 60, 62, 67,68,69, 73,74,75,76]. The current review findings are in line with previous reviews that found improvement in QoL post-CI [77,78,79]. For example, Andries et al. 2021, found improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) pre- and post-CI. Andries et al. study examined HRQoL in older adults only, but the current review examined general QoL and HRQoL, health service utilisation and other social outcomes both in younger and older adults. It seems that CI users felt they confidently communicated which resulted in improvements in health-related or general QoL. Prior research has also indicated improved communicative ability through rehabilitation resulted in improved QoL in older adults [80, 81].

The current review found a link between CI and anxiety or depression, with most included studies identifying improvements [59, 60, 62]. The current review is consistent with prior research which found improvements in internalising mental health conditions [82,83,84,85,86]. Improvements in mental health from pre-CI were seen in the first 6 months but diminished after a long-term follow-up at 12 months post-CI in a study of 20 older adults [62]. Several factors could explain these results including users may relate their expectations to unrealistic outcomes, such as device limitations and its maximum benefits post-CI [87].

In this review, CI was found to improve cognitive functions such as immediate memory, attention, and delayed memory subdomains at 12 months post-CI. In older adults, CI was associated with improved cognitive functions mainly by improving the attention domain [54, 61, 62]. These results corroborate previous research findings that found CI was associated with improvement in cognitive function in older adults [80, 82, 88, 89].

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review were that it followed the PRISMA guidelines, the search strategy was developed by consulting a university librarian, and dual screening and data extraction was conducted. Despite these strengths, there are limitations for this review. First, most studies reported results based on small sample sizes, which made it difficult to generalise findings to larger populations. Second, the validity of questionnaires for measuring outcomes such as social participation, autonomy or perceived hearing disability in included studies were not known. Studies have used different measurement tools for the same social outcomes, this may lead to variation in patient outcomes or inaccuracy of measured outcomes. Third, post-operative complications of care may not have been observed, or may be underreported, in the included studies. For example, these studies may have only been conducted with CI users who use their cochlear implant, limiting the knowledge that could be gained from CI users who may have stopped using their devices.

Conclusions

Despite identifying small body of evidence regarding health service utilisation, this review found benefits of CI in improving adults’ health service utilisation and social outcomes. Improvement in hearing and communication ability was shown to enhance social interactions and working life, and also to support independence in everyday life. However, the review highlights the need for large scale and well-designed epidemiological studies to measure health and social outcomes.

Data Availability

All data generated during this study are included in this systematic review and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Cochlear implant

- HRQoL:

-

Health related quality of life

- NR:

-

Not reported

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

GBD Collaborators. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996–1009.

Ye X, Zhu D, He P. The role of self-reported hearing status in the risk of hospitalisation among chinese middle-aged and older adults. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(10):754–61.

Genther DJ, Frick KD, Chen D, Betz J, Lin FR. Association of hearing loss with hospitalization and burden of disease in older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2322–4.

Mick P, Foley DM, Lin FR. Hearing loss is associated with poorer ratings of patient–physician communication and healthcare quality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2207–9.

Jiam NT-L, Li C, Agrawal Y. Hearing loss and falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(11):2587–96.

McKee MM, Moreland C, Atcherson SR, Zazove P. Hearing loss: communicating with the patient who is deaf or hard of hearing. FP Essent. 2015;434:24–8.

Barnett DD, Koul R, Coppola NM. Satisfaction with health care among people with hearing impairment: a survey of Medicare beneficiaries. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(1):39–48.

DeWalt DA, Boone RS, Pignone MP. Literacy and its relationship with self-efficacy, trust, and participation in medical decision making. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(1):27–S35.

Idstad M, Engdahl B. Childhood sensorineural hearing loss and educational attainment in adulthood: results from the HUNT study. Ear Hear. 2019;40(6):1359–67.

Järvelin MR, Mäki-Torkko E, Sorri MJ, Rantakallio PT. Effect of hearing impairment on educational outcomes and employment up to the age of 25 years in northern finland. Br J Audiol. 1997;31(3):165–75.

Furlonger B. An investigation of the career development of high school adolescents with hearing impairments in New Zealand. Am Ann Deaf. 1998;143(3):268–76.

Vas VF. The biopsychosocial impact of hearing loss on people with hearing loss and their communication partners [Ph.D thesis]. Ann Arbor: The University of Nottingham (United Kingdom); 2017.

Mousavi Z, Movallali G, Nare N. Adolescents with deafness: a review of self-esteem and its components. Auditory and Vestibular Research. 2017;26.

Shukla A, Harper M, Pedersen E, Goman A, Suen JJ, Price C, et al. Hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(5):622–33.

Blazer DG. Hearing loss: the silent risk for psychiatric disorders in late life. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(1):19–27.

Linszen MM, Brouwer RM, Heringa SM, Sommer IE. Increased risk of psychosis in patients with hearing impairment: review and meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;62:1–20.

Theunissen SC, Rieffe C, Kouwenberg M, Soede W, Briaire JJ, Frijns JH. Depression in hearing-impaired children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(10):1313–7.

Bierbaum M, McMahon CM, Hughes S, Boisvert I, Lau AYS, Braithwaite J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to cochlear implant uptake in Australia and the United Kingdom. Ear Hear. 2020;41(2):374–85.

Ye X, Zhu D, Wang Y, Chen S, Gao J, Du Y et al. Impacts of the hearing aid intervention on healthcare utilization and costs among middle-aged and older adults: results from a randomized controlled trial in rural China. Lancet Reg Health - Western Pac. 2022:100594.

Hoff S, Ryan M, Thomas D, Tournis E, Kenny H, Hajduk J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of cochlear implantation of young children, including those with complicating conditions. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(4):454–63.

Boisvert I, Reis M, Au A, Cowan R, Dowell RC. Cochlear implantation outcomes in adults: a scoping review. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2020;15(5):e0232421.

Abrar R, Mawman D, Martinez de Estibariz U, Datta D, Stapleton E. Simultaneous bilateral cochlear implantation under local anaesthesia in a visually impaired adult with profound sensorineural deafness: a case report. Cochlear implant Int. 2021;22(3):176–81.

Amin N, Wong G, Nunn T, Jiang D, Pai I. The outcomes of cochlear implantation in elderly patients: a single united kingdom center experience. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100(5suppl):842S–7S.

Lin FR, Chien WW, Li L, Clarrett DM, Niparko JK, Francis HW. Cochlear implantation in older adults. Medicine. 2012;91(5):229–41.

Dornhoffer JR, Reddy P, Meyer TA, Schvartz-Leyzac KC, Dubno JR, McRackan TR. Individual differences in speech recognition changes after cochlear implantation. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(3):280–6.

McRackan TR, Velozo CA, Holcomb MA, Camposeo EL, Hatch JL, Meyer TA, et al. Use of Adult patient focus groups to develop the initial item bank for a cochlear implant quality-of-life instrument. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(10):975–82.

Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Harris MS, Moberly AC. Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;3(4):240–54.

Moberly AC, Bates C, Harris MS, Pisoni DB. The enigma of poor performance by adults with cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(10):1522–8.

Moberly AC, Lowenstein JH, Nittrouer S. Word recognition variability with cochlear implants: “perceptual attention” versus “auditory sensitivity. Ear & Hearing. 2016;37(1):14–26.

Malzanni GE, Lerda C, Battista RA, Canova C, Gatti O, Bussi M, et al. Speech recognition, quality of hearing, and data logging statistics over time in adult cochlear implant users. Indian J Otology. 2022;28(1):45–51.

Blamey P, Artieres F, Başkent D, Bergeron F, Beynon A, Burke E, et al. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiol Neurootol. 2013;18(1):36–47.

Mahmoud AF, Ruckenstein MJ. Speech perception performance as a function of age at implantation among postlingually deaf adult cochlear implant recipients. Otology & Neurotology. 2014;35(10).

Boisvert I, McMahon CM, Dowell RC. Speech recognition outcomes following bilateral cochlear implantation in adults aged over 50 years old. Int J Audiol. 2016;55:39–S44.

Buchman CA, Herzog JA, McJunkin JL, Wick CC, Durakovic N, Firszt JB, et al. Assessment of speech understanding after cochlear implantation in adult hearing aid users: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 2020;146(10):916–24.

Ovari A, Hühnlein L, Nguyen-Dalinger D, Strüder DF, Külkens C, Niclaus O, et al. Functional outcomes and quality of life after cochlear implantation in patients with long-term deafness. J Clin Med. 2022;11:17.

Nijmeijer HGB, Keijsers NM, Huinck WJ, Mylanus EAM. The effect of cochlear implantation on autonomy, participation and work in postlingually deafened adults: a scoping review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(9):3135–54.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Hoffman HJ. Hearing loss grades and the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(10):725–8.

WHO. World report on hearing. Geneva; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

WHO. A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. Kobe (Japan). 2004.

Health, AIo. Welfare. The international classification of functioning, disability and health. Canberra: AIHW; 2002.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP cohort study checklist. 2018a.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative study checklist. 2018c.

Goh T, Bird P, Pearson J, Mustard J. Educational, employment, and social participation of young adult graduates from the paediatric Southern Cochlear Implant Programme, New Zealand. Cochlear Implants International: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2016;17(1):31–51.

Ross L, Lyon P. Escaping a silent world: profound hearing loss, cochlear implants and household interaction. Int J Consumer Stud. 2007;31(4):357–62.

Vieira SS, Dupas G, Chiari BM. Effects of cochlear implantation on adulthood. Codas. 2018;30(6):e20180001.

Spencer LJ, Tomblin JB, Gantz BJ. Growing up with a cochlear implant: education, vocation, and affiliation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2012;17(4):483–98.

Raymond MJ, Dong A, Naissir SB, Vivas EX. Postoperative Healthcare utilization of Elderly adults after cochlear implantation. Otology & Neurotology. 2020;41(2).

Carpenter RM, Limb CJ, Francis HW, Gottschalk B, Niparko JK. Programmatic challenges in obtaining and confirming the pneumococcal vaccination status of cochlear implant recipients. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(8):1334–6.

Guitar K, Giles E, Raymond B. D W. Health effects of cochlear implants. J New Z Med Association. 2013;126(1375).

Chapman M, Dammeyer J. The relationship between cochlear implants and deaf identity. Am Ann Deaf. 2017;162(4):319–32.

Hogan A, Hawthorne G, Kethel L, Giles E, White K, Stewart M, et al. Health-related quality-of-life outcomes from adult cochlear implantation: a cross-sectional survey. Cochlear Implants Int. 2001;2(2):115–28.

Sonnet MH, Montaut-Verient B, Niemier JY, Hoen M, Ribeyre L, Parietti-Winkler C. Cognitive abilities and quality of life after cochlear implantation in the elderly. Otology & Neurotology. 2017;38(8):e296–e301.

Völter C, Götze L, Dazert S, Falkenstein M, Thomas JP. Can cochlear implantation improve neurocognition in the aging population? Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:701–12.

Kos MI, Degive C, Boex C, Guyot JP. Professional occupation after cochlear implantation. J Laryngology Otology. 2007;121(3):215–8.

Rembar S, Lind O, Arnesen H, Helvik AS. Effects of cochlear implants: a qualitative study. Cochlear Implants Int. 2009;10(4):179–97.

Clinkard D, Barbic S, Amoodi H, Shipp D, Lin V. The economic and societal benefits of adult cochlear implant implantation: a pilot exploratory study. Cochlear implant Int. 2015;16(4):181–5.

Monteiro E, Shipp D, Chen J, Nedzelski J, Lin V. Cochlear implantation: a personal and societal economic perspective examining the effects of cochlear implantation on personal income. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d’oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2012;41 Suppl 1:S43–8.

Mo B, Harris S, Lindbaek M. Cochlear implants and health status: a comparison with other hearing-impaired patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(11):914–21.

Mo B, Lindbæk M, Harris S. Cochlear implants and quality of life: a prospective study. Ear Hear. 2005;26(2).

Mertens G, Andries E, Claes AJ, Topsakal V, Van de Heyning P, Van Rompaey V, et al. Cognitive improvement after cochlear implantation in older adults with severe or profound hearing impairment: a prospective, longitudinal, controlled, multicenter study. Ear & Hearing. 2021;42(3):606–14.

Claes AJ, Van de Heyning P, Gilles A, Van Rompaey V, Mertens G. Cognitive performance of severely hearing-impaired older adults before and after cochlear implantation: preliminary results of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study using the RBANS-H. Otology & Neurotology. 2018;39(9):e765–e73.

Terry B, Kelt RE, Jeyakumar A. Delayed complications after cochlear implantation. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2015;141(11):1012–7.

Halawani R, Aldhafeeri A, Alajlan S, Alzhrani F. Complications of post-cochlear implantation in 1027 adults and children. Ann Saudi Med. 2019;39(2):77–81.

Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2011;66A(10):1131–6.

Gagliardi AR, Yip CYY, Irish J, Wright FC, Rubin B, Ross H, et al. The psychological burden of waiting for procedures and patient-centred strategies that could support the mental health of wait-listed patients and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2021;24(3):978–90.

Issing C, Baumann U, Pantel J, Stöver T. Cochlear implant therapy improves the quality of life in older patients—a prospective evaluation study. Otology & Neurotology. 2020;41(9).

Czerniejewska-Wolska H, Kałos M, Sekula A, Piszczatowski B, Rutkowska J, Rogowski M, et al. Quality of life and hearing after cochlear implant placement in patients over 60 years of age. Otolaryngol Pol. 2015;69(4):34–9.

Issing C, Holtz S, Loth AG, Baumann U, Pantel J, Stover T. Long-term effects on the quality of life following cochlear implant treatment in older patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(11):5135–44.

Ganek HV, Feness M-L, Goulding G, Liberman GM, Steel MM, Ruderman LA, et al. A survey of pediatric cochlear implant recipients as young adults. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;132:109902.

Ferguson MA, Kitterick PT, Chong LY, Edmondson-Jones M, Barker F, Hoare DJ. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):Cd012023.

Hixon B, Chan S, Adkins M, Shinn JB, Bush ML. Timing and impact of hearing healthcare in adult cochlear implant recipients: a rural-urban comparison. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(9):1320–4.

Härkönen K, Kivekäs I, Kotti V, Sivonen V, Vasama JP. Hybrid cochlear implantation: quality of life, quality of hearing, and working performance compared to patients with conventional unilateral or bilateral cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(10):3599–604.

Looi V, Mackenzie M, Bird P. Quality-of-life outcomes for adult cochlear implant recipients in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2011;124(1340):4.

Härkönen K, Kivekäs I, Rautiainen M, Kotti V, Sivonen V, Vasama J-P. Sequential bilateral cochlear implantation improves working performance, quality of life, and quality of hearing. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135(5):440–6.

Hawthorne G, Hogan A, Giles E, Stewart M, Kethel L, White K, et al. Evaluating the health-related quality of life effects of cochlear implants: a prospective study of an adult cochlear implant program. Int J Audiol. 2004;43(4):183–92.

McRackan TR, Bauschard M, Hatch JL, Franko-Tobin E, Droghini HR, Nguyen SA, et al. Meta-analysis of quality-of-life improvement after cochlear implantation and associations with speech recognition abilities. Laryngoscope. 2017;128(4):982–90.

McRackan TR, Bauschard M, Hatch JL, Franko-Tobin E, Droghini HR, Velozo CA, et al. Meta-analysis of cochlear implantation outcomes evaluated with general health-related patient-reported outcome measures. Otology and Neurotology. 2018;39(1):29–36.

Andries E, Gilles A, Topsakal V, Vanderveken OM, Van de Heyning P, Van Rompaey V, et al. Systematic review of quality of life assessments after cochlear implantation in older adults. Audiol Neuro-otol. 2021;26(2):61–75.

Mosnier I, Bebear JP, Marx M, Fraysse B, Truy E, Lina-Granade G, et al. Improvement of cognitive function after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(5):442–50.

Clark JH, Yeagle J, Arbaje AI, Lin FR, Niparko JK, Francis HW. Cochlear implant rehabilitation in older adults: literature review and proposal of a conceptual framework. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1936–45.

Carasek N, Lamounier P, Maldi IG, Bernardes MND, Ramos HVL, Costa CC et al. Is there benefit from the use of cochlear implants and hearing aids in cognition for older adults? A systematic review. Front Epidemiol. 2022;2.

Acar B, Yurekli MF, Babademez MA, Karabulut H, Karasen RM. Effects of hearing aids on cognitive functions and depressive signs in elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(3):250–2.

Castiglione A, Benatti A, Velardita C, Favaro D, Padoan E, Severi D, et al. Aging, cognitive decline and hearing loss: effects of auditory rehabilitation and training with hearing aids and cochlear implants on cognitive function and depression among older adults. Audiol Neurotology. 2016;21(suppl 1):21–8.

Choi JS, Betz J, Li L, Blake CR, Sung YK, Contrera KJ, et al. Association of using hearing aids or cochlear implants with changes in depressive symptoms in older adults. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2016;142(7):652–7.

Contrera KJ, Sung YK, Betz J, Li L, Lin FR. Change in loneliness after intervention with cochlear implants or hearing aids. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(8):1885–9.

Lachowska M, Pastuszka A, Glinka P, Niemczyk K. Is cochlear implantation a good treatment method for profoundly deafened elderly? Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1339–46.

Calvino M, Sanchez-Cuadrado I, Gavilan J, Gutierrez-Revilla MA, Polo R, Lassaletta L. Effect of cochlear implantation on cognitive decline and quality of life in younger and older adults with severe-to-profound hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(10):4745–59.

Yeo BSY, Song H, Toh EMS, Ng LS, Ho CSH, Ho R et al. Association of hearing aids and cochlear implants with cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2022.

Aldhafeeri AM, Alzhrani F, Alajlan S, AlSanosi A, Hagr A. Clinical profile and management of revision cochlear implant surgeries. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(2):223–7.

Chen J, Chen B, Shi Y, Li Y. A retrospective review of cochlear implant revision surgery: a 24-year experience in China. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(3):1211–20.

Gumus B, İncesulu AS, Kaya E, Kezban Gurbuz M, Ozgur Pınarbaslı M. Analysis of cochlear implant revision surgeries. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(3):675–82.

Huarte A, Martinez-Lopez M, Manrique-Huarte R, Erviti S, Calavia D, Alonso C, et al. Work activity in patients treated with cochlear implants. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola. 2017;68(2):92–7.

Kay-Rivest E, Friedmann DR, McMenomey SO, Jethanamest D, Thomas Roland J Jr, Waltzman SB. The Frailty phenotype in older adults undergoing cochlear implantation. Otology & Neurotology. 2022;43(10):e1085–e9.

Park E, Shipp DB, Chen JM, Nedzelski JM, Lin VYW. Postlingually deaf adults of all ages derive equal benefits from unilateral multichannel cochlear implant. J Am Acad Audiol. 2011;22(10):637–43.

Sorrentino T, Coté M, Eter E, Laborde M, Cochard N, Deguine O, et al. Cochlear reimplantations: technical and surgical failures. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129(4):380–4.

Cole KL, Babajanian E, Anderson R, Gordon S, Patel N, Dicpinigaitis AJ, et al. Association of baseline frailty status and age with postoperative complications after cochlear implantation: a national inpatient sample study. Otology & Neurotology. 2022;43(10):1170–5.

Fazel MZ, Gray RF. Patient employment status and satisfaction following cochlear implantation. Cochlear implant Int. 2007;8(2):87–91.

Krabbe PF, Hinderink JB, van den Broek P. The effect of cochlear implant use in postlingually deaf adults. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(3):864–73.

Marschark M, Walton D, Crowe K, Borgna G, Kronenberger WG. Relations of social maturity, executive function, and self-efficacy among deaf university students. Deafness & Education International. 2018;20(2):100–20.

O’Neill Erin R, Basile John D, Nelson P. Individual hearing outcomes in cochlear implant users influence social engagement and listening behavior in everyday life. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2021;64(12):4982–99.

Saxon JP, Holmes AE, Spitznagel RJ. Impact of a cochlear implant on job functioning. 2001;67:49–54.

Fitzpatrick EM, Carrier V, Turgeon G, Olmstead T, McAfee A, Whittingham J, et al. Benefits of auditory-verbal intervention for adult cochlear implant users: perspectives of users and their coaches. Int J Audiol. 2022;61(12):993–1002.

Hogan A, Stewart M, Giles E. It’s a whole new ball game! Employment experiences of people with a cochlear implant. Cochlear implant Int. 2002;3(1):54–67.

Mäki-Torkko EM, Vestergren S, Harder H, Lyxell B. From isolation and dependence to autonomy - expectations before and experiences after cochlear implantation in adult cochlear implant users and their significant others. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(6):541–7.

Pulik Ł, Jaśkiewicz K, Sarzyńska S, Małdyk P, Łęgosz P. Modified frailty index as a predictor of the long-term functional result in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty. Reumatologia. 2020;58(4):213–20.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–43.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

Glickman N, Carey J. Measuring deaf cultural identities: a preliminary investigation: Erratum. Rehabil Psychol. 1994;39:Winter 1993 issue with an excessive number of typographical errors.

Maxwell-McCaw DL. Acculturation and psychological well-being in deaf and hard -of -hearing people [Ph.D thesis]. United States, District of Columbia: The George Washington University; 2001.

Claes AJ, Mertens G, Gilles A, Hofkens-Van den Brandt A, Fransen E, Van Rompaey V, et al. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status for hearing impaired individuals before and after cochlear implantation: a protocol for a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:512.

Hinderink JB, Krabbe PF, Van Den Broek P. Development and application of a health-related quality-of-life instrument for adults with cochlear implants: the Nijmegen cochlear implant questionnaire. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(6):756–65.

Noble W, Jensen NS, Naylor G, Bhullar N, Akeroyd MA. A short form of the Speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale suitable for clinical use: the SSQ12. Int J Audiol. 2013;52(6):409–12.

Stern AF. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med. 2014;64(5):393–4.

Gatehouse S, Noble W. The speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale. Int J Audiol. 2004;43(2):85–99.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(2):113–28.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5.

Pavot W, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess. 1991;57(1):149–61.

Hawthorne G, Hogan A. Measuring disability-specific patient benefit in cochlear implant programs: developing a short form of the Glasgow Health Status Inventory, the hearing participation scale. Int J Audiol. 2002;41(8):535–44.

Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Browning GG. Measuring patient benefit from otorhinolaryngological surgery and therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105(6):415–22.

Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):328–36.

Hawthorne G, Richardson J. Measuring the value of program outcomes: a review of multiattribute utility measures. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2001;1(2):215–28.

Conrad I, Matschinger H, Riedel-Heller S, Von Gottberg C, Kilian R. The psychometric properties of the german version of the WHOQOL-OLD in the german population aged 60 and older. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:105.

Torrance GW, Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Barr RD, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2 Med Care. 1996;34(7):702–22.

Castellanos I, Kronenberger WG, Pisoni DB. Questionnaire-based assessment of executive functioning: Psychometrics. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2018;7(2):93–109.

Kronenberger WG, Colson BG, Henning SC, Pisoni DB. Executive functioning and speech-language skills following long-term use of cochlear implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2014;19(4):456–70.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Wexler M, Miller LW, Berliner KI, Crary WG. Psychological effects of cochlear implant: patient and index relative perceptions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1982;91(2 Pt 3):59–61.

Crary WG, Wexler M, Berliner KI, Miller LW. Psychometric studies and clinical interviews with cochlear implant patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1982;91(2 Pt 3):55–8.

Ware J, Snoww K, Ma K, Bg G. SF36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric, Inc, 1993. 1993;30.

Sandanger I, Moum T, Ingebrigtsen G, Dalgard OS, Sørensen T, Bruusgaard D. Concordance between symptom screening and diagnostic procedure: the Hopkins symptom checklist-25 and the Composite International Diagnostic interview I. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(7):345–54.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist: a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15.

Cheng AK, Niparko JK. Cost-utility of the cochlear implant in adults: a meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(11):1214–8.

Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear. 1982;3(3):128–34.

Cox RM, Alexander GC. The abbreviated profile of hearing aid benefit. Ear Hear. 1995;16(2).

Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31(12):721–7.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86.

Leplège A, Perret-Guillaume C, Ecosse E, Hervy MP, Ankri J. von Steinbüchel N. A new instrument to measure quality of life in older people: the french version of the WHOQOL-OLD. Rev Med Interne. 2013;34(2):78–84.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98.

von Frenckell R, Lottin T. Validation of a depression threshold: the Hamilton scale. Encephale. 1982;8(3):349–54.

Power M, Quinn K, Schmidt S, Group W-O. Development of the WHOQOL-Old module. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(10):2197–214.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to CochlearLTD and Macquarie University for jointly funding this study. The authors wish to thank the Macquarie University medical librarians for their support in searching strategies for articles and the Professional and Community Engagement (PACE) students for assisting with screening and data extractions.

Funding

This study was jointly supported by the CochlearLTD and Macquarie University. The funders had no role in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation or writing this systematic review or the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TBO searched, screened all relevant articles, extracted the data, assessed quality and drafted the manuscript. RL and RM checked the screened articles, reviewed the extracted data and edited the manuscript. All authors provided comments on the draft manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekele Okuba, T., Lystad, R.P., Boisvert, I. et al. Cochlear implantation impact on health service utilisation and social outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 929 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09900-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09900-y