Abstract

Background

Quality healthcare services are considered one of the most effective vehicles for healthcare managers to achieve organizational goals. Therefore, this study aimed to combine the findings of comparable studies to identify consistencies and contradictions in the quality of outpatient services in Iran.

Methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted in 2022 according to PRISMA guideline. All relevant English and Persian studies were searched in databases, including Web of Sciences, PubMed, Scopus, Scientific Information Database, and Magiran. No year restriction was applied. The quality of the studies was assessed by the 22-item Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. The meta-analysis was conducted by using Open Meta Analyst, and between-study heterogeneity was investigated with I-squared statistic.

Results

Of the 106 retrieved articles, seven studies with a total sample size of 2600 were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled estimate of mean for overall perception was 3.95 (95% CI: 3.34- 4.55, P< 0.001, I2= 99.97), while the pooled estimate of the mean for the overall expectation was 4.43 (95% CI: 4.11- 4.75, P< 0.001, I2= 99.93). The highest and lowest perception mean scores were related to tangibility (3.52, Gap= -0.86) and responsiveness (3.30, Gap= -1.04) dimensions.

Conclusion

Responsiveness was identified as the weakest dimension. Therefore, managers are recommended to design suitable workforce-development programs which focus on the provision of timely and prompt services, polite and courteous interactions with patients, and prioritization of patients’ needs. Moreover, training public sector practitioners along with incentives can fill up the existing gaps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In today's competitive environment, the quality of services is one of the most effective vehicles for healthcare managers to achieve organizational goals. High-quality services can increase patient satisfaction and generate loyalty and trust [1, 2]. One of the main challenges of healthcare systems worldwide is the provision of quality services with limited resources. A good healthcare system must balance quality, cost and resource allocation [3]. Specific characteristics of healthcare systems, such as heterogeneity, intangibility, and simultaneity have made the definition of quality more difficult. Crosby defines quality as conformation to specification [4]. In contrast, Deming describes it as services and products designed to satisfy the needs and expectation of customers [5]. Similarly, Parasuraman defines quality as meeting customer expectations [6].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) health system framework, service quality bridges structural blocks and outcomes. If services are not of sufficient quality, healthcare systems will fail in reaching their final goals, i.e., people’s health [7]. Based on WHO report, between 5.7 and 8.4 million deaths are attributed to poor quality of care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) which accounts for approximately 15% of all deaths in these countries. Also, inadequate quality of care costs is estimated $1.4 to $1.6 trillion per year in lost productivity in LMICs [8, 9]. As a lower-middle-income country, Iran has taken significant measures to improve service quality, universal health coverage, and health system's responsiveness. The latest measure is the Health Transformation Plan (HTP) which was first implemented in 2014 to enhance public access to healthcare services and facilities of high quality. Therefore, some measures were taken to improve the quality of outpatient services, increase the number of specialists, and improve hospital facilities and hoteling services [10, 11].

The quality of outpatient services is of great importance because outpatient departments are the first point of contact when patients visit hospitals. They are one of the most important sources of patient flow to hospital inpatient departments; consequently, the manner of service delivery in these departments plays an important role in patients' overall perception of hospital services and their decisions for hospitalization [12]. It is expected that in the future, due to new technologies and shorter waiting time, outpatient departments will have the same or more income for hospitals than inpatient departments [13, 14].

In Iran, the quality of inpatient services and primary health care was investigated in several systematic review studies; however, the quality of outpatient services was neglected [15,16,17]. Therefore, the present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis combining the findings of comparable studies to identify consistencies and contradictions in the quality of outpatient services in Iran.

Methods

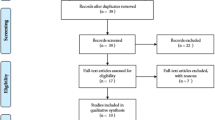

The current study was conducted in 2022 according to PRISMA guideline. The processes consist of the following steps; identification process, screening process, eligibility criteria, and selection of articles [18]. In cases where agreement could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted.

Identification process

Publications were searched in national and international databases, including Web of Sciences, PubMed, Scopus, Scientific Information Database (SID), and Magiran. Using MeSH headings, we searched for the terms: “service quality”, “quality of services”, “health quality”, “quality of health care”, “outpatient”, “outpatient clinics, hospital”, “ambulatory”, “ambulatory care”, and “Iran”. No year restriction was applied. The full search strategy in PubMed is highlighted in Table 1. These searches were supplemented by screening grey literature sources, including Google Scholar database, relevant reports, and conference abstracts.

Screening process

The study followed PRISMA guidelines for the screening process. The retrieved records were exported to Endnote X8 software, and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (PF and EZ) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies the full text of which were retrieved for detailed review and data extraction.

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to select studies: (1) Original articles; (2) Studies on hospital outpatient clinics; (3) Studies reporting the mean scores of service quality dimensions from patients’ viewpoints; (4) The availability of full text articles; and (5) Articles published in English and Persian. Outpatient care is defined as a service or treatment provided by outpatient departments in hospitals (private or public) where the patients are not hospitalized. Therefore, studies on clinical (technical) quality as well as studies conducted in clinics outside hospitals, such as dental clinics, pharmacies, etc., were excluded from the study.

Study selection

The full texts of all included studies were independently checked by two authors. All eligible or potentially eligible studies were assessed by the third author once again. Additionally, the 22-item Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [19] was used to assess the quality of the studies. A score between 0 and 7 was considered low quality, 8 and 17 as moderate, and 18 and 22 as high quality. A standard data collection form was used to collect data on author(s), publication year, research design, data collection tool(s), service quality dimensions, as well as the mean scores of the weakest and strongest service quality dimensions.

Synthesis methods

Between-study heterogeneity was investigated with I-squared (I2) statistic. All data related to mean and standard deviation (SD) as effect size were extracted from the included studies and transferred to standard error (SE). The meta-analysis was conducted by using Open Meta Analyst, and random effects model was used to estimate the overall effect size and was expressed as standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Meta-analysis was conducted based on the overall perception and overall expectation; moreover, subgroup analyses were performed based on tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy dimensions. Due to random effects, equal weights were given to the studies, and the weights were not reported. Similarly, there was no need to report the funnel plot [20] since the number of final studies was less than 10.

Results

Of the 106 retrieved articles, seven studies met our criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The studies were all quantitative and cross-sectional, and a questionnaire, developed by researchers, was used to collect data and the mean scores were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. In 70% of the studies (7 out of 10), the SERVQUAL questionnaire was used for data collection, and 60% of the studies (n=6) were conducted in Tehran and published in Persian. The total number of participants was 2600, and the minimum and maximum sample size varied between 200 and 650. The studies were conducted on service quality dimensions, i.e., tangibility, reliability, assurance, responsiveness, empathy, accessibility, physician’s consultation, providing information to patient, physical environment, perceived service costs, appointment, waiting time, and admission process. Eight studies, due to insufficient results and poor quality, were excluded, e.g. Tabibi et al. [21], Abedi et al. [22], and Yavari et al. [23]. In addition, three studies by Zarei et al. [12], Khalili et al. [24], and Abbasi-Moghaddam et al. [14] were disqualified from the synthesis phase because they used various data collection techniques and obtained disparate results.

As indicated in Table 2, 40% of the studies reported the lowest and highest mean scores for responsiveness and tangibility dimensions, respectively. The highest and lowest overall mean scores of patients’ perception were reported in studies by Ghobadi et al. (4.15 ±0.14) [25] and Havasbeigi et al. (2.78 ±0.21) [26], in that order. Furthermore, the largest and smallest gaps between patients’ perceptions and expectations were reported by Farrokhi et al. (gap= -1.55) [27] and, Bastani et al. (gap= -0.57) [28] (Table 3).

Perception

There was a high heterogeneity between the studies which can be attributed to different population, setting, gender, and age of the participants. According to the random effect model, the pooled estimate of mean for overall perception was 3.95 (95% CI: 3.34- 4.55, P< 0.001, I2= 99.97; see Fig 2). Also, regarding the dimensions, the pooled estimate of mean was 3.49 (95% CI: 2.71- 4.28, P< 0.001) for the assurance dimension, 3.31 (95% CI: 2.79- 3.82, P< 0.001) for the empathy dimension, 3.49 (95% CI: 2.84- 4.13, P< 0.001) for the reliability dimension, 3.30 (95% CI: 2.63- 3.99, P< 0.001 for the responsiveness dimension, and 3.52 (95% CI: 3.19- 3.85, P< 0.001) for the tangibility dimension (Table 4).

Expectation

According to the random effect model, the pooled estimate of the mean for the overall expectation was 4.43 (95% CI: 4.11- 4.75, P< 0.001, I2= 99.93; see Fig 3). Also, regarding the dimensions, the pooled estimate of mean was 4.37 (95% CI: 4.10- 4.64, P< 0.001) for the assurance dimension, 4.33 (95% CI: 4.01- 4.66, P< 0.001) for the empathy dimension, 4.43 (95% CI: 4.07- 4.80, P< 0.001) for the reliability dimension, 4.35 (95% CI: 4.03- 4.67, P< 0.001) for the responsiveness dimension, and 4.38 (95% CI: 4.04- 4.71, P< 0.001) for the tangibility dimension (Table 4).

The pooled estimate of the mean scores for perception and expectation was calculated: the overall gap between them was -0.48 which was equal to -0.88, -1.02, -0.94, -1.04, and -0.86 for assurance, empathy, reliability, responsiveness, and tangibility dimensions, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

For the first time, this study aimed to systematically review the available evidence on outpatient service quality in Iran. The overall mean score of outpatients’ perception (3.95) and expectation (4.43) about the quality of outpatient services illustrates a negative quality gap (-0.48) indicating that patients do not receive expected services, in other words, there is a gap between their expectations and the provided services, and their expectations are not sufficiently met. These results are consistent with Rezaei et al.’s study [15] which indicated that the overall mean scores of patients’ perception, expectation, and the gap between them were 3.69, 4.59, and -0.9, respectively. Similarly, in other studies by Teshnizi et al. [16] and Gilavand & Torabipour [32], the overall service quality gaps in health care centers were -1.64 and -0.86, in that order. Moreover, the overall service quality gap in primary healthcare services was found to be -0.83 by Gorji et al. [17] and -0.53 by Rahmani et al. [33]. Totally, outpatient service quality in Iran is in a good condition which can be attributed to factors, such as shorter length of stay, low out-of-pocket payment, and short-term treatment results.

The lowest overall perception mean score (3.30) was found to be related to the responsiveness dimension which obtained the lowest mean scores in four studies (40%). Responsiveness refers to organizational readiness to help patients, the behavior and attitude of the staff, waiting time and the provision of prompt services. It seems that the appointment and timely service delivery processes in outpatient centers were not satisfactory due to overcrowding, weak motivators, and lack of training of employees in answering patients' questions [27, 28, 31]. Similarly, a study in Turkey reported responsiveness and empathy as the lowest perceived dimensions (5.7 out of 9) [1]. In contrast, the results of a study in private hospitals in Syria showed the highest mean score (4.17) for responsiveness [34].

The highest overall perception mean score was related to the tangibility (3.52) dimension, i.e., organizations’ physical facilities, equipment, and the appearance of the personnel. According to the results, the patients were more satisfied with the tangibility dimension. In accordance with these findings, previous study by Qolipour et al. on service quality of medical tourism in private and public hospitals demonstrated that the tangibility dimension obtained the highest perception mean score and the lowest quality gap (3.92, Gap= -0.68) [35].

Furthermore, the highest and lowest quality gaps were related to the dimensions of responsiveness (-1.04) and tangibility (-0.86) which corroborate the findings of previous works [32, 36, 37] in which the highest quality gap was related to the responsiveness dimension. Therefore, it seems that adequate number of professional human resources and reduction in patient waiting time can help the improvement of this dimension. A systematic review by Batbaatar et al. showed that patients who had to wait longer in the outpatient department, without prior notice, tended to be less satisfied with the overall services [38]. In contrast, a study on the quality of outpatient services in Saudi Arabia indicated the highest gap (-1.42) in the tangibility dimension [39].

Study limitations

However, these findings are subject to publication bias, a problem that can distort the obtained estimations. Publication bias arises from aspects, such as language bias, multiple publications, selective outcome reporting, poor methodological design, and inadequate data analysis. The insufficient number of studies did not allow us to perform further analysis, such as funnel plots.

Conclusion

According to the results, few studies have been conducted on outpatient service quality which requires further attention by researchers. Moreover, it is suggested that researchers simultaneously measure the quality of outpatient, inpatient and primary care to understand why patient are more satisfied with outpatient services. The results of the current study can be used to better identify the strengths and weaknesses of outpatient services rendered by health organizations in Iran. Therefore, it is recommended that managers design suitable workforce-development programs focusing on the provision of timely and prompt services, polite and courteous interactions with patients, and prioritization of patients’ needs. Additionally, training public sector practitioners along with incentives can fill up the existing gaps.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- HTTP:

-

Health Transformation Plan

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- I2 :

-

I-squared

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean differences

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Pekkaya M, Pulatİmamoğlu Ö, Koca H. Evaluation of healthcare service quality via Servqual scale: an application on a hospital. Int J Healthc Manag. 2019;12(4):340–7.

Zarei E, Bagheri A, Daneshkohan A, Khodakarim S. Patients’ views on service quality in selected Iranian hospitals: an importance-performance analysis. Shiraz E-Med J. 2020;21(9).

Marzo R, Bhattacharya S, Ujang N, Naing TW, Fei A, Chun CK, et al. The impact of service quality provided by health-care centers and physicians on patient satisfaction. Int J Health Promot. 2021;10:160.

Crosby P. Quality is free-if you understand it. Winter Park Public Library History and Archive Collection. 1979:4.

Deming WE. Out of the Crisis, reissue: MIT press; 2018 Oct 16.

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J Mark. 1985;49(4):41–50.

Manyazewal T. Using the World Health Organization health system building blocks through survey of healthcare professionals to determine the performance of public healthcare facilities. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(1):50.

World Health Organization. Quality health services: a planning guide. 2020.

Berwick D, Snair M, Nishtar S. Crossing the global health care quality chasm: a key component of universal health coverage. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1317–8.

Harirchi I, Hajiaghajani M, Sayari A, Dinarvand R, Sajadi HS, Mahdavi M, et al. How health transformation plan was designed and implemented in the Islamic Republic of Iran? Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:121.

Moradi-Lakeh M, Vosoogh-Moghaddam A. Health sector evolution plan in Iran; equity and sustainability concerns. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(10):637.

Zarei E. Service quality of hospital outpatient departments: patients’ perspective. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015;28(8):778–90.

Carlucci D, Renna P, Schiuma G. Evaluating service quality dimensions as antecedents to outpatient satisfaction using back propagation neural network. Health Care Manag Sci. 2013;16(1):37–44.

Abbasi-Moghaddam MA, Zarei E, Bagherzadeh R, Dargahi H, Farrokhi P. Evaluation of service quality from patients’ viewpoint. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–7.

Rezaei S, Hajizadeh M, Zandian H, Fathi A, Nouri B. Service quality in Iranian hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. MJIRI. 2018;32(1):344–51.

Teshnizi SH, Aghamolaei T, Kahnouji K, Teshnizi SMH, Ghani J. Assessing quality of health services with the SERVQUAL model in Iran. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(2):82–9.

Gorji HA, Royani S, Mohseni M, Azami-Aghdash S, Moosavi A, Sheyklo SG. Primary health care quality in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Med Prim Care Rev. 2019;21(1):71–7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-9.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Jamalodin TS, Reza GM, Mohammad SB, Somayeh S. The impact of service quality on the loyalty of patients referring to outpatient clinics of studied hospitals in Tehran. Payavard Salamat. 2012;6(3):25–34.

Abedi G, Rostami F, Ziaee M, Siamian H, Nadi A. Patient’s perception and expectations of the quality of outpatient services of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Sari City. Mater Socio Med. 2015;27(4):272.

Yavari Z, Mohammad-Shafiee M, Ghauor F. Evaluating the service quality of selected specialized medical clinics in Shiraz city, Iran, using servqual model. Health Inf Manag J. 2018;14(6):236–42.

Khalili H, Sameti A. Healthcare quality and medicine reimbursement criteria in Iran. Int J Pharm Healthc. 2017;11(4):455–70.

Ghobadi H, Mehrnoush N, Hamidkholgh G, Amani F. Measuring the quality of services provided for outpatients in Kowsar Clinic in Ardebil City based on the SERVQUAL Model. Res Sci J Ardabil Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2014;14(4):387–79.

Havasbeigi F, Ahmadi A, Yasbolaghis B, Mohamadi E. A survey of the quality of the provided services by public hospitals of Ilam and Kermanshah city to the out-patients on the basis of SERVQUAL model. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2010;21(4):207–14.

Farrokhi P, Aryankhesal A, Bagherzadeh R, Aghaei HA. Evaluation of outpatient service quality: what do patients and providers think? Int J Healthc Manag. 2022;15(4):1–10.

Bastani P, Barati O, Sadeghi A, Sharifi S, Abhari S. Analysis of service quality gap in outpatient wards using SERVQUAL model in Shahid Motahhari clinic of Shiraz in 2014. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2016;14(12):1015–32.

Tabibi SJ, Gohari MR, Shahri S, Aghababa S. Assessment of health care services in outpatient clinics based on SERVQUAL model in hospitals of Tehran. Payavard Salamat. 2012;5(4):49–56.

Khaki M, Kargar M, Parham M, Mohebi S. Survey the quality of provided services in out-patient’s clinics of Shiraz training hospitals based on the model of SERVQUAL in 2014. Iran J Nurs Res. 2015;10(3):12–34.

Haghshenas E, Arab M, Rahimi FA, Movahed E. Assessing the quality of services provided at outpatient clinics among hospitals affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences based on SERVQUAL Model in 2015. Hospital. 2017;16(2):9–17.

Gilavand A, Torabipour A. The quality of services of Iran University hospitals based on SERVQUAL's evaluation model: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Front. 2022;10.

Rahmani H, Maleki R, Ghanbari MK, Behzadifar M. Quality assessment of services in primary healthcare in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32(2):453–62.

AlOmari F. Measuring gaps in healthcare quality using SERVQUAL model: challenges and opportunities in developing countries. Meas Bus Excell. 2021;25(4):407–20.

Qolipour M, Torabipour A, Khiavi FF, Malehi AS. Assessing medical tourism services quality using SERVQUAL model: a patient’s perspective. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(1):103.

Aghamolaei T, Eftekhaari TE, Rafati S, Kahnouji K, Ahangari S, Shahrzad ME, et al. Service quality assessment of a referral hospital in Southern Iran with SERVQUAL technique: patients’ perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–5.

Došen ĐO, Škare V, Čerfalvi V, Benceković Ž, Komarac T. Assessment of the quality of public hospital healthcare services by using SERVQUAL. Acta Clin Croat. 2020;59(2):285–92.

Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101.

Al Fraihi KJ, Famco D, Latif SA. Evaluation of outpatient service quality in Eastern Saudi Arabia: Patient’s expectations and perceptions. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(4):420.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the authors and publishers of the original studies.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PF conceived the study. PF and EZ searched for relevant literature, extracted data, and drafted the manuscript. MAZ analyzed and interpreted data. PF, EZ, and RB assisted with the search, revising, and writing of the manuscript. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Farrokhi, P., Bagherzadeh, R., Arab-Zozani, M. et al. Assessing the quality of hospital outpatient services in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 508 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09506-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09506-4