Abstract

Introduction

Out-of-pocket payments for healthcare remain a significant health financing challenge in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), preventing women from using maternal health services. There is a paucity of empirical literature on the influence of health insurance coverage on the timeliness of antenatal care (ANC) attendance in low- and middle-income countries. In this study, we examined the association between health insurance coverage and timely ANC attendance among pregnant women in SSA.

Methods

Secondary data from Demographic and Health Surveys conducted between 2015 and 2020 in sixteen (16) sub-Saharan African countries with 113,918 women aged 15-49 years were included in the analysis. The outcome variable was the timing of antenatal care (ANC). A multilevel binary logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the association between health insurance coverage and timely ANC.

Results

The overall coverage of health insurance and timely antenatal attendance among pregnant women in SSA were 4.4% and 39.0% respectively. At the country level, the highest coverage of health insurance was found in Burundi (24.3%) and the lowest was in Benin (0.9%). For timely ANC attendance, the highest prevalence was in Liberia (72.4%) and the lowest was in Nigeria (24.2%). The results in the model showed that women who were covered by health insurance were more likely to have timely ANC attendance compared to those who were not covered by health insurance (aOR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.11-1.31).

Conclusion

Our findings show that that being covered under health insurance is associated with higher likelihood of seeking timely ANC attendance. To accelerate progress towards achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal targets by the year 2030, we recommend that governments and health insurance authorities across the sub-Saharan African countries actively implement health insurance policies as well as roll out health educational programmes that facilitate and ensure increased coverage of health insurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Achieving universal health coverage (UHC) is integral to the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly indicator 3.8.2 which seeks to identify people who spend greater than 10 or 25% of their household expenditure or income, respectively on health [1, 2]. UHC in this context denotes a situation where every individual and all communities have unparalleled access to quality health services without suffering any form of financial hardship [3]. This conceptualisation raises concerns about equity, quality, and financial risk protection [4]. Although the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the World Bank have been at the forefront of championing UHC due to the severe fiscal implications that are associated with UHC, its implementation has been largely driven by individual countries and states [5, 6]. Hence, different countries have adopted different mechanisms to arrive at UHC.

Prioritisation of health financing systems through health insurance schemes appears to be universal [4]. For example, countries such as China which has a population of over 1.3 billion people ensures health insurance coverage for its populace [7]. Several countries including the USA [8], Taiwan [9], and France [10] have all instituted national health insurance. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), countries like Ghana [3] and Nigeria [11] have health insurance schemes that aims to promote UHC and limit catastrophic health expenditure. Health insurance can either be a tax-financed government scheme, social health insurance, private compulsory health insurance and voluntary health insurance (i.e., private voluntary health insurance schemes and community-based health insurance) [12].

In most countries within SSA, health insurance offers greater opportunity for the population, especially, the vulnerable and those in poor economic status to have access to healthcare at any point in time [13]. One of such vulnerable populations that tends to benefit substantially from national health insurance coverage is pregnant women [13]. In some countries like Ghana, the government through an act of parliament (ACT 650) set up the national health insurance scheme in 2003, which exempts pregnant women from the payment of national health insurance premiums [14]. This is done as a means to encourage more pregnant women to enroll onto the national health insurance scheme [14]. Likewise, Nigeria in 2005 instituted their national health insurance scheme which offers 90% payment for the cost of drugs and healthcare while the subscriber paid only 10% of the cost of drugs [12].

Pregnant women are at risk of developing complications such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, anemia, severe persistent nausea, vomiting, and gestational diabetes [15]. Hence, antenatal care (ANC) becomes imperative to the health and wellbeing of the expectant mother and the unborn child [15]. For example, during ANC, pregnant women are provided with Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy [IPTp] for malaria control [16]. Moreover, through ANC attendance, the expectant mother and the unborn child benefit from nutrition and health checks, opportunity to detect high-risk pregnancy, counselling, and support for women and their families, as well as an increased propensity to have skilled birth delivery which may translate into a significant decline in the risk of maternal and neonatal mortality [17, 18].

Evidences from Ghana [19], Ethiopia [20], and Kenya [21] indicates that uptake of ANC is associated with maternal education, level of media exposure, region, place of residence, household wealth, place of delivery, marital status, age at first marriage, knowledge of ANC attendance, partner’s education and birth order. In relation to health insurance coverage, there is a plethora of evidence to suggest that health insurance coverage is significantly associated with ANC attendance among pregnant women [19, 22]. However, the question remains, to what extent does health insurance coverage influence not only the uptake of ANC attendance but more importantly, the timeliness of the attendance? This question remains less examined by the existing scholarship on health insurance coverage and ANC attendance. Timely ANC in this context refers to the ANC attendance for which the first contact occurred within the first 12 weeks (gestational period), with the subsequent ones occurring at 4-week intervals [23, 24]. Delaying ANC may result in serious deleterious consequences on the expectant mother and the unborn child, as well as exacerbate the risk of maternal morbidity and mortality [23, 24]. To address this concern of timeliness in ANC attendance, we examined the association between national health insurance coverage and timely ANC attendance among pregnant women in SSA.

Methods

Data source and study design

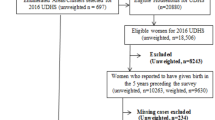

We analysed data from the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) of sixteen (16) countries in SSA. Countries were considered for inclusion into the study if they had dataset between 2015-2020 as well as have complete cases of variables of interest. In this study, the data were extracted from the women’s file (IR Recode) of the selected countries. The DHS is a nationally representative survey usually conducted periodically in over 85 low- and middle-income countries [25]. DHS employed a cross-sectional design in collecting data from the respondents. A two-stage sampling technique was employed to collect data from the respondents. Data on several health indicators such as maternal health care service utilisation, maternal and child health, nutrition, reproductive health, domestic violence, and men’s health was collected using a structured questionnaire [25]. The detailed survey methodology and sampling methods has been highlighted in a previous study [26]. A total of 113,918 women aged 15-49 years with complete observations were included in the analysis (Table 1). We relied on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement in writing the manuscript [27]. The dataset is freely available for download at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was the timing of antenatal care (ANC) attendance. The WHO defined the timing of ANC as the period in pregnancy during when the first ANC was sought [23]. To assess this variable, the women were asked “How many months pregnant were you when you first received ANC for this pregnancy? The response options to this question was recoded as ≤3 months or >3 months. The women with first ANC attendance in ≤3 months were categorised as having “timely ANC attendance” whilst those with ANC attendance in >3 months were said to have “late ANC attendance”. This categorisation has been used by studies that used the DHS dataset [20, 28, 29].

Key explanatory variable

Health insurance coverage was the key explanatory variable. In assessing this variable, the women were asked the question “Are you covered by any health insurance?”. The response options were “No” and “Yes”. The use of health insurance coverage as a key explanatory variable was informed by studies that used the DHS dataset [14, 28].

Covariates

A total of fifteen (15) variables were studied as covariates. The selection of the variables was informed by literature [20, 28,29,30,31,32] as well as their availability in the DHS datasets. The variables have been categorised into individual-level factors and contextual-level factors (Household/community factor).

Individual factors

The individual level factors were maternal age (15-19; 20-24; 25-29; 30-34; 35-39; 40-44; and 45-49), level of education (no education; primary; secondary; and higher), marital status (Never married; married; cohabiting; widowed; divorced; and separated), current working status (yes and no), religion (Christianity; Islamic; African Traditional; No religion; and Others), frequency of listening to radio (not at all; less than once a week, at least once a week; and almost every day), frequency of watching television (not at all; less than once a week, at least once a week; and almost every day), frequency of reading newspapers/magazines (not at all; less than once a week, at least once a week; and almost every day), getting medical help for self: permission to go (not a big problem and big problem), getting medical help for self: money to go (not a big problem and big problem), and getting medical help for self: distance to facility (not a big problem and big problem). Parity was recoded as “1”, “2”, “3”, and “4 or more”.

Household/community factors

Wealth index, place of residence, and studied countries were the contextual-level factors. From the DHS dataset, wealth index was coded as “poorest”, “poorer”, “middle”, “richer”, and “richest”. Sex of household head was coded as “male” and “female”. The age of household head was coded as “below 25”, “25-34”, “35-44”, and “45 and above”. Place of residence was coded as “urban” and “rural”. All 16 countries were included as a household/community level variables.

Statistical analyses

We performed the data analysis using Stata software version 16.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). First, percentages were used to present the results of the coverage of health insurance and timely ANC (Fig. 1). A Pearson chi-square test of independence was used to examine the relationship between health insurance, individual-level factors, contextual-level factors, and timely ANC (Table 2). All the variables that showed significance were placed in the regression model. We performed a multilevel binary logistic regression using four models to determine the association between health insurance and timely ANC controlling for the individual and household/community level factors (Table 3). We adopted multilevel regression analysis because of the complex structure of the DHS dataset [33]. Unlike the traditional regression, multilevel regression analysis best suites a hierarchical dataset structure similar to that of the DHS dataset, hence, its usage in the current study [34]. Also, the multilevel regression allowed us to incorporate variables measured at different levels of the hierarchy [34]. Model 0 showed the variance in timely ANC attributed to the clustering of the primary sampling units (PSUs) the health insurance and studied covariates. Model I was fitted to contain health insurance and individual-level factors. Model II contained the household/community-level factors. Model III was finally fitted to comprise of HEALTH INSURANCE, individual-level and household/community-level factors. We employed the Stata command “melogit” in fitting the four models. Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) tests for Model comparison was also used in the analysis. All the results were presented using adjusted odds ratios (aOR) at 95% Confidence Interval (CI). The women’s sample weight (v005/1,000,000) and the ‘svy’ command were used to correct for over and under-sampling, including the complex survey design to improve our findings’ generalisability. Hatt and Waters [35], argued that pooling data can reveal broader results that are “often obscured by the noise of individual data sets.” Therefore to calculate the pooled values an additional adjustment is needed to account for the variability in the number of individuals sampled in each country. This was achieved by using the weighting factor 1/(A*nc/nt), where A is the number of countries asked a particular question, nc is the number of respondents for the country c, and nt is the total number of respondents over all countries asked the question [36].

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not sought for this study since the data is freely available in the public domain. From the DHS reports, ethical clearance was sought and all ethical guidelines governing the use of human subjects in research were strictly adhered to. The detailed ethical guidelines are available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study is available at DHS dataset, http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Results

Health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance among pregnant women in SSA

The overall coverage of health insurance and timely ANC attendance among pregnant women in SSA were 4.4% and 39.0% respectively. At the country level, the highest coverage of health insurance was found in Burundi (24.3%) with the lowest coverage in Benin (0.9%). For timely ANC attendance, the highest prevalence was in Liberia (72.4%) and the lowest in Nigeria (24.2%) (Fig. 1).

Bivariable analysis of health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance among pregnant women in SSA

Table 2 presents the results on the distribution of timely ANC among pregnant women in SSA across health insurance coverage and women’ socio-demographic characteristics. With health insurance coverage, the results showed significant differences across timing of ANC at p<0.005. Specifically, timely ANC was higher among pregnant women who were covered by health insurance (51.8%) compared to those who were not covered by health insurance (38.4%). All the socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women also showed significant differences in the timing of ANC, except getting medical help for self: permission to go.

Multilevel regression analysis of health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance among pregnant women in SSA

Measure of association (Fixed effect results)

Table 3 shows results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis of the association between health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance among pregnant women in SSA while controlling for significant covariates. The last model (Model III), which contained health insurance and all the covariates was considered the best-fit model (AIC=142918.2). The results in the model showed that women who were covered by health insurance were more likely to have timely ANC attendance compared to those who were not covered by health insurance (aOR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.11-1.31).

With the covariates, timely ANC was higher among pregnant women of all age categories compared to women aged 15-19. Compared to pregnant women with no formal education, those with at least primary education were more likely to have timely ANC attendance, with the highest odds among those with higher education (aOR=1.56, 95% CI= 1.41,1.72). Women of all statuses of marriage were more likely to have timely ANC attendance compared to never married pregnant women. Pregnant women who were exposed to newspaper/magazine, radio, and television were more likely to have timely ANC attendance compared to those who were not exposed to any of these media sources. A higher likelihood of timely ANC attendance was found among pregnant women of the richest wealth index compared to those of the poorest wealth index (aOR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.26-1.47). Pregnant women who lived in rural areas were more likely to go for ANC attendance on time compared to those who lived in urban areas (aOR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.12-1.25). The odds of timely ANC decreased with parity with women who had four or more children having the lowest odds of timely ANC attendance (aOR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.64-0.73).

Measure of association (Random effect results)

The results from Table 3 showed a minute variation in timely ANC across the PSUs in the empty model (Model O) [σ2 =0.196; 95% (CI =0.165–0.232)]. In the Intra-Class Correlation (ICC), an approximately 6% (0.056) of the total variance was attributed to the between clusters differences of the communities were the pregnant women resided. The ICC decreased from about 5% (0.054) in Model I to 2% (0.024) in Model III. Hence, the study observed a decrease in variation across all the models attributable to the residential communities of the pregnant women. Also, the AIC values showed a significant reduction from 151099 in Model O to 142918.2 in Model III. As a result, Model III was adopted as the best fitted model for the study.

Discussion

Overall, coverage of health insurance and timely ANC attendance was low, at 4.4 and 39.0 percent respectively. This low prevalence observed in our study poses a serious public health concern and a likely staller for attaining the SDG target 3.8.2. While the general prevalence of timely ANC attendance and coverage of health insurance was low, our study observed that there was some level of heterogeneity with respect to inter-country variations. For example, Liberia had the highest prevalence of timely ANC attendance (72.4%) whereas Burundi recorded the highest coverage of health insurance (24.3%). Contextual evidence from Liberia reveals that maternal health care has been improving substantially since the end of the Liberian civil war in 1999, and is evident in the timing of the first ANC attendance [37]. Thus, explaining the high level of timely ANC attendance as observed in the present study. In the case of Burundi, the government with external support from implementation partners provided a complete exemption for the cost of healthcare services for pregnant women in 2006 [38]. This could explain the relatively high coverage of health insurance in Burundi as compared to a country like Ghana that implemented free maternal health care later in 2008.

The results from this study also revealed that health insurance coverage was significantly associated with timely ANC attendance among pregnant women as those covered by the health insurance having a higher likelihood of reporting timely ANC attendance. This finding corroborates earlier studies [37] that have found health insurance coverage to have a significant association with the odds of reporting timely ANC attendance. Previous studies [19, 22] have found that health insurance coverage is quintessential in eliminating out-of-pocket payments and significantly removing the financial barriers that often limit women’s capacity to attend ANC on time. Thus, serving as a motivating factor that encourages pregnant women to seek timey ANC attendance.

Education emerged as a significant covariate in our analyses. Pregnant women with no formal education were less likely to have timely ANC attendance as compared to those who had formal education. Our study further shows that among pregnant women with formal education, those who had secondary or higher education tend to have a higher likelihood of reporting timely ANC attendance as compared to their counterparts who have only primary education. The result is substantiated by previous studies from Ghana [19], Ethiopia [20], and Kenya [21] which found a higher likelihood in the uptake and timeliness of ANC attendance. A plausible explanation to this finding could be that women who have secondary or higher education are more likely to be exposed to the mass media which serves as a conduit for educating women, particularly about the relevance of attending ANC on time as well as the dangers of delaying ANC attendance. Another justifiable reason for this finding could be that pregnant women with higher levels of education tend to be empowered and are therefore able to take critical decisions concerning their reproductive health in an autonomous manner. Hence, the likelihood of delaying ANC attendance is significantly reduced while increasing the odds of timely ANC attendance. This also explains why women who were exposed to the mass media (i.e., newspaper/magazine, radio, and television) were more likely to have timely ANC attendance.

Compared to unmarried pregnant women, married pregnant women were more likely to have timely ANC attendance. An analogous finding was reported by Sakeah et al. [19]. This result is best explained from the socio-cultural perspective. In most courtiers within the sub-Saharan African region, pregnancy out of wedlock is taboo and is further exacerbated by the religious indoctrinations that portray pregnancy out of wedlock as sinful [39, 40]. As such, unmarried women who get pregnant find it difficult to attend ANC, and those that gather the courage to attend ANC often delay [39, 40]. This delay comes as a defensive mechanism to avoid stigma and ridicule from society as well as from healthcare providers [39, 40]. Another plausible explanation could be that unmarried women may sometimes find it difficult to access the financial resource needed to seek timely ANC attendance , particularly in areas where national health coverage is extremely low and there is no complete exemption for the cost of healthcare to pregnant women [19].

After controlling for other variables, pregnant women in rural areas were more likely to have timely ANC attendance. This finding is contrary to that of previous studies that higher risk of delayed initiation of ANC among rural dwelling women as compared to urban women, mainly due to the presence of substantial barriers in rural communities, such as issues of long-distance to health care facilities and unavailability of health facilities [19, 20]. Plausibly, this could be attributed to the busy and strenuous work demands of urban-dwelling women which makes it difficult for them to initiate ANC visits early as compared to women residing in rural settlements.

We also found a higher likelihood of timely ANC attendance among pregnant women of the richest wealth index compared to those of the poorest wealth index. The poorest women tend to suffer several challenges with respect to being able to afford health care as well as being capable of making decisions concerning their reproductive health and health promotive behaviors [41]. Hence, making them less likely to seek timely ANC attendance. Our study also revealed that the odds of timely ANC attendance decrease with higher parity. Multiparous women the lowest odds of timely ANC attendance. This finding confirms a related study conducted in Ethiopia [42] that found multiparous women to have the lowest likelihood of achieving timely ANC attendance. Given that multiparous women have greater experience with childbirth, they are likely to feel more confident about handling their pregnancy [42]. As such, they are likely to have lower perception about the relevance of ANC compared with primiparous women who are often inexperienced and will, therefore, feel inadequate to handle their pregnancy [42]. Hence, uniparous women have greater tendency to have timely ANC attendance.

Strengths and limitations

Nationally representative data were employed to examine the association between health insurance coverage and timely ANC attendance among pregnant women. This provided a wider coverage for our study that makes the findings statistically generalisable to the 16 sub-Saharan African countries included in the study. Moreover, we used robust analytical tools that make our study replicable and valid. Nevertheless, some inherent limitations must be taken into consideration during the interpretation of our findings. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the dataset used, causal inference cannot be established. Also, the data was self-reported, hence, there is the possibility of recall bias and social desirability.

Conclusion

Based on the findings from our study, we conclude that being covered by health insurance is associated with a higher likelihood of seeking timely ANC attendance. For this reason, we recommend that governments and national health insurance authorities across the sub-Saharan African countries to actively implement health insurance policies as well as roll out health educational programs that will facilitate and ensure high coverage of health insurance. Moreover, our study shows that higher level of education, wealth index, and urban residency are facilitating factors for timely ANC attendance. Therefore, it is imperative for the various governments across the sub-region to invest intensively in female education as well as improving the socio-economic status of women. This will ensure greater success in Africa’s quest to eliminate delayed ANC attendance, and rather promote timely attendance. Given that exposure to the mass media is an important factor in influencing timely ANC, attendance we recommend that the TV, radio, and newspapers be used as a conduit of delivering critical, accurate information and education about the importance of seeking timely ANC attendance and the potential dangers of delaying ANC.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study is available at: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- DHSs:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Derakhshani N, Doshmangir L, Ahmadi A, Fakhri A, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Gordeev VS. Monitoring Process Barriers and Enablers Towards Universal Health Coverage Within the Sustainable Development Goals: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:459.

United Nations. SDG Indicators Metadata repository. [Internet]. Retrieved: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=3&Target=3.8

World Health Organization. Together on the road to universal health coverage: A call to action. World Health Organization;2017.

Agbadi P, Okyere J, Lomotey A, Duah HO, Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO. Socioeconomic and demographic correlates of nonenrolment onto the national health insurance scheme among children in Ghana: Insight from the 2017/18 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Prev Med Rep. 2021;22:101385.

Rodin J, de Ferranti D. Universal health coverage: the third global health transition? Lancet (London, England). 2012;380(9845):861–2.

Pisani E, Olivier Kok M, Nugroho K. Indonesia’s road to universal health coverage: a political journey. Health Policy Plann. 2017;32(2):267–76.

Yu H. Universal health insurance coverage for 1.3 billion people: what accounts for China’s success? Health Policy. 2015;119(9):1145–52.

Knapp CD, Howell BA, Wang EA, Shlafer RJ, Hardeman RR, Winkelman TN. Health insurance gains after implementation of the Affordable Care Act among individuals recently on probation: USA, 2008–2016. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1086–8.

Shih YR, Liao KH, Chen YH, Lin FJ, Hsiao FY. Reimbursement Lag of New Drugs Under Taiwan's National Health Insurance System Compared With United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(5):916–22.

Grodner C, Sbidian E, Weill A, Mezzarobba M. Epidemiologic study in a real-world analysis of patients with treatment for psoriasis in the French national health insurance database. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(2):411–6.

Oladimeji AO, Adewole DA, Adeniji F. The bypassing of healthcare facilities among National Health Insurance Scheme enrollees in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int Health. 2021;13(3):291–6.

Barasa E, Kazungu J, Nguhiu P, Ravishankar N. Examining the level and inequality in health insurance coverage in 36 sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(4):e004712.

Amo-Adjei J, Anku PJ, Amo HF, Effah MO. Perception of quality of health delivery and health insurance subscription in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–1.

Ameyaw EK, Ahinkorah BO, Baatiema L, Seidu AA. Is the National Health Insurance Scheme helping pregnant women in accessing health services? Analysis of the 2014 Ghana demographic and Health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–8.

Graham A, Devarajan S, Datta S. Complications in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2015;25(1):1–5.

Appiah PK, Bukari M, Yiri-Erong SN, Owusu K, Atanga GB, Nimirkpen S, Kuubabongnaa BB, Adjuik M. Antenatal care attendance and factors influenced birth weight of babies born between June 2017 and may 2018 in the WA East district, Ghana. Int J Reprod Med. 2020;19:1–10.

Tadele N, Lamaro T. Utilization of institutional delivery service and associated factors in Bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia: community based, cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–0.

Mbuagbaw L, Medley N, Darzi AJ, Richardson M, Garga KH, Ongolo-Zogo P. Health system and community level interventions for improving antenatal care coverage and health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD010994.

Sakeah E, Okawa S, Rexford Oduro A, Shibanuma A, Ansah E, Kikuchi K, et al. Determinants of attending antenatal care at least four times in rural Ghana: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1291879.

Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M, Shah V, Kadio B, Udenigwe O. Timing and adequate attendance of antenatal care visits among women in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184934.

Wairoto KG, Joseph NK, Macharia PM, Okiro EA. Determinants of subnational disparities in antenatal care utilisation: a spatial analysis of demographic and health survey data in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–2.

Manzi A, Munyaneza F, Mujawase F, Banamwana L, Sayinzoga F, Thomson DR, et al. Assessing predictors of delayed antenatal care visits in Rwanda: a secondary analysis of Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):1–8.

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: World Health Organization; 2016.

Tuncalp O, Pena-Rosas JP, Lawrie T, Bucagu M, Oladapo OT, GA PA. WHO recommendation on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience–going beyond survival. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14599.

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1602–13.

Aliaga A, Ruilin R. Cluster optimal sample size for demographic and health surveys. In 7th International Conference on Teaching Statistics–ICOTS, vol. 7; 2006. p. 2–7.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strobe Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, Odusina EK, Keetile M, Yaya S. Examining barriers to healthcare access and utilization of antenatal care services: evidence from demographic health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–6.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, Mohammed A, Adu C, Agbaglo E, et al. Factors associated with the number and timing of antenatal care visits among married women in Cameroon: evidence from the 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. J Biosocial Sci. 2021;26:1–1.

Seidu AA. Factors associated with early antenatal care attendance among women in Papua New Guinea: a population-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):1–9.

Gebremeskel F, Dibaba Y, Admassu B. Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in Arba Minch Town and Arba Minch District, Gamo Gofa Zone, South Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. 2015;12:2015.

Manyeh AK, Amu A, Williams J, Gyapong M. Factors associated with the timing of antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–7.

Bell A, Fairbrother M, Jones K. Fixed and random effects models: making an informed choice. Qual Quantity. 2019;53(2):1051–74.

Austin PC, Goel V, van Walraven C. An introduction to multilevel regression models. Can J Public Health. 2001;92(2):150–4.

Hatt LE, Waters HR. Determinants of child morbidity in Latin America: a pooled analysis of interactions between parental education and economic status. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):375–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.007 PMID: 16040175.

Peng YK, Hight-Laukaran V, Peterson AE, Perez-Escamilla R. Maternal nutritional status is inversely associated with lactational amenorrhea in Sub-Saharan Africa: results from demographic and health surveys II and III. J Nutr. 1998;128(10):1672–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/128.10 PMID: 9772135.

Luginaah IN, Kangmennaang J, Fallah M, Dahn B, Kateh F, Nyenswah T. Timing and utilization of antenatal care services in Liberia: Understanding the pre-Ebola epidemic context. Soc Sci Med. 2016;160:75–86.

Edu BC, Agan TU, Monjok E, Makowiecka K. Effect of free maternal health care program on health-seeking behaviour of women during pregnancy, Intra-partum and Postpartum Periods in Cross River State of Nigeria: A Mixed Method Study. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. 2017;5(3):370.

Gibson-Davis C, Rackin H. Marriage or carriage? Trends in union context and birth type by education. J Marriage Fam. 2014;76(3):506–19.

Su JH, Dwyer EA. Repackaging Fatherhood: Father Engagement and Cooperative Coparenting in Mid-Pregnancy Marriages and Cohabitations. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82(5):1625–36.

Jacobs C, Michelo C, Moshabela M. Why do rural women in the most remote and poorest areas of Zambia predominantly attend only one antenatal care visit with a skilled provider? A qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Abuka T, Alemu A, Birhanu B. Assessment of timing of first antenatal care booking and associated factors among pregnant women who attend antenatal Care at Health Facilities in Dilla town, Gedeo zone, southern nations, nationalities and peoples region, Ethiopia, 2014. J Preg Child Health. 2016;3(258):2.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Measure DHS for granting us access to the data used for this study.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G.A., A.S., H.A. and B.O.A conceived the idea. J.O., R.G.A. and B. Z wrote the main text of the manuscript. H.A., A.S., B.O.A., and S.Y. prepared the tables and figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. J.O. was tasked with the final duty of submitting and correspondence.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not a requirement in this study since secondary data which is available in the public domain was used. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available can be found at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

A.S. is an associate editor for the BMC Health Services Research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aboagye, R.G., Okyere, J., Ahinkorah, B.O. et al. Health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 181 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07601-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07601-6