Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has caused significant healthcare service disruptions. Surgical backlogs have been estimated but not for other healthcare services. This study aims to estimate the backlog of preventive care services caused by COVID-19.

Methods

This observational study assessed preventive care screening rates at three primary care clinics in Ottawa, Ontario from March to November 2020 using data from 22,685 electronic medical records. The change in cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, and type 2 diabetes screening rates were crudely estimated using 2016 census data, estimating the volume of key services delayed by COVID-19 across Ontario and Canada.

Results

The mean percentage of patients appropriately screened for cervical cancer decreased by 7.5% (− 0.3% to − 14.7%; 95% CI), colorectal cancer decreased by 8.1% (− 0.3% to − 15.8%; 95% CI), and type 2 diabetes decreased by 4.5% (− 0.2% to − 8.7%; 95% CI). Crude estimates imply 288,000 cervical cancer (11,000 to 565,000; 95% CI), 326,000 colorectal cancer (13,000 to 638,000; 95% CI), and 274,000 type 2 diabetes screenings (13,000 to 535,000; 95% CI) may be overdue in Ontario. Nationally the deficits may be tripled these numbers. Re-opening measures have not reversed these trends.

Interpretation

COVID-19 decreased the delivery of preventive care services, which may cause delayed diagnoses, increased mortality, and increased health care costs. Virtual care and reopening measures have not restored the provision of preventive care services. Electronic medical record data could be leveraged to improve screening via panel management. Additional, system-wide primary care and laboratory capacity will be needed to restore pre-COVID-19 screening rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 has strained our healthcare system and workforce in unprecedented ways and these effects are gradually being understood. Ministry of Health directives significantly reduced the volume of surgical procedures completed since March 2020 [1]. However, COVID-19’s impact on health care delivery extends beyond the operating room. Screening volumes decreased drastically shortly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and in many cases have not returned to baseline levels [2]. Yet the volume of patients that are now due for screening according to clinical guidelines has yet to be quantified. Screening services are important for early cancer detection and treatment. Delays in cancer diagnosis and treatment significantly increase mortality rates [3]. Much of this screening is performed by primary care providers in community clinics. The Ontario Ministry of Health has advised that community clinics limit in-person appointments, favouring virtual care assessments instead [4]. Many preventive care services do not require in-person assessments and may still be provided through virtual care [5]. However, many provincial screening programs were paused at the beginning of the pandemic [6,7,8,9]. In Ontario, restrictions on colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) lasted almost six months, lifting for high priority patients as of August 25, 2020 [10].

While non-official reports indicate that cancer screening has decreased, there is still limited data that quantifies the volume of delayed preventive care services. Electronic medical record (EMR) data could help provide insight into this deficit [11]. EMRs provide a longitudinal history of patients’ health and statuses, including provision of preventive care services [11]. Primary care EMR data uniquely combines internally produced data with imported data from laboratories, imaging centers, specialists, and acute care [12]. Accordingly, primary care EMR data may provide timely information on health outcomes and service delivery for health system planning and research purposes. This study utilized primary care EMR data to quantify the impact of COVID-19 on the delivery of preventive care services, namely cervical cancer, CRC, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) screening. It is expected that the number of patients screened has decreased since COVID-19 restrictions began.

Methods

Preventive care data sources

This was an observational cohort study. Data was extracted from three urban primary care clinics in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Two clinics were academic family health teams, and one was a community family health organization. All three clinics used PS Suites, which is provided by TELUS Health [13]. A scheduled data export was developed using PS Suites’ built-in scheduled reports functionality [12]. The scheduled report identified all active patient records and output each patient’s age, gender, past medical history, and select preventive care data in a tab delimited file. The scheduled reports ran every week from March 15, 2020, until November 29, 2020. Preventive care data necessary to determine compliance with the Canadian Task Force for Preventive Health Care’s (CTFPHC) recommendations were exported. The number of months since the latest Papanicolaou smear was exported for cervical cancer screening and are represented by four data points [14]. The number of months since the latest fecal occult blood test (FOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy were exported for CRC screening [15]. The number of months since and results of the latest hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and fasting blood sugar (FBS) were exported for T2DM screening [16]. See Additional file 4 for details of exported data. A separate manual review of 900 charts was completed to validate the exported data and confirmed data accuracy. These 900 charts were randomly selected from consenting providers’ patient panels. The primary investigator first reviewed 300 charts manually and identified which screening tests were due according to the low-risk guidelines used here. The manual chart review was then compared to the algorithm used in this study. Inconsistencies were identified from these 300 charts and the algorithm adjusted before an additional 600 charts were reviewed. This validation has not yet been published but is available upon request from the authors.

Determining the impact on screening rates

Screening statuses for cervical cancer, CRC, and T2DM were determined from the exported EMR data. The analysis was completed using a Python 3.8 script, which analyzed the exported tab delimited files. The Python script determined each patients’ screening eligibility in agreement with the latest screening recommendations for cervical cancer [14], CRC [15], and T2DM [16, 17] (Table 1). Since insufficient data was available to calculate the T2DM risk (CANRISK score) [18] a minimum screening interval of 3 years was used instead, which aligns with both the CTFPHC [16] and Diabetes Canada [17] guidelines. Patients considered high risk or ineligible for screening were excluded from the analysis. Full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria algorithm are available in Additional files 1, 2, and 3.

After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, each primary care providers’ patient panel was assessed, determining the percentage of patients that were up to date for cervical cancer, CRC, and T2DM screening. If screening was completed within the recommended interval, then that patient was counted as up to date for that screening maneuver.

Once the percentage of patients up to date for the three screening tests was determined for each provider’s patient panel, then the mean percentage of patients up to date was determined for all providers. The mean percentage was determined to keep each provider’s screening rates confidential. The weekly mean percentages of patients up to date on preventive care screening were then graphed chronologically, including key dates from Ontario’s COVID-19 response [19]. Finally, the change in mean percentage of patients up to date for screening between March 15, 2020, and November 29, 2020, was determined.

The impact of COVID-19 on in-person preventive care (cervical cancer screening), provincial screening programs (CRC screening), and screening that could be delivered through virtual care without restriction (T2DM screening) was estimated based on the change in mean from the beginning of the pandemic response [5].

Crude estimates of the provincial and National Preventive Care Service Deficits

Crude estimates of the preventive care service deficits for Ontario and Canada were calculated based on the study clinics’ experience with service disruptions due to COVID-19. Census data from 2016 [20] were used to estimate the number of people in Ontario and Canada that are due for cervical cancer, CRC, and T2DM screening from baseline levels.

Statistical analysis

The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the mean percentage of all providers’ patients that are up to date on cervical cancer, CRC, and T2DM screening were determined using a normal approximation method.

Ethics approval

Patient consent was not required as was determined by the Bruyère Research Ethics Board at Bruyère Hospital in Ottawa, Ontario. REB Ethics Number: #M16–20-045. All required privacy and security measures were followed to maintain patient confidentiality.

Results

Practice demographics

The demographics of the three clinics is presented in Tables 2 and 3. Data was extracted from 22,685 active patients on a weekly basis across 29 providers. On November 29, 2020, there were 6754 patients eligible for cervical cancer screening and 492 were excluded since they met high risk or exclusion criteria according to Canadian screening guidelines. A total of 7168 were eligible for colorectal cancer screening and 200 were excluded. Lastly, 10,933 met eligibility criteria for type 2 diabetes screening and 1469 met the exclusion criteria. The numbers from March 15, 2020, were also reported for reference.

Impact of COVID-19 on mean preventive care screening rates

The period of data collection covered 38 weeks from March 15, 2020, until November 29, 2020. Two weeks of data were excluded due to errors in the scheduled data export causing incomplete data to be exported.

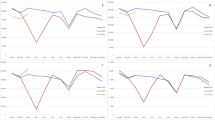

During the 38 weeks since March 15, 2020, the mean preventive care screening rates decreased for cervical cancer screening (Fig. 1), colorectal cancer screening (Fig. 2), and type 2 diabetes screening (Fig. 3). Cervical cancer screening rates decreased by 7.5% (− 0.3% to − 14.7%; 95% CI). The mean colorectal cancer screening rates decreased by 8.1% (− 0.3% to − 15.8%; 95% CI). The mean type 2 diabetes screening rates decreased by 4.5% (− 0.2% to − 8.7%; 95% CI).

Cervical Cancer Screening Rates. Shows the mean percentage (percentage screened ± SD) of eligible patients up to date for cervical cancer screening each week (n = 6765 March 15, 2020; n = 6754 November 29, 2020). For reference the lockdown and re-opening stages have been identified. Lockdown = March 20, 2020, Stage 2 = June 12, 2020, Stage 3 = July 17, 2020, and Modified Stage 2 = October 13, 2020

Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates. Shows the mean percentage (percentage screened ± SD) of eligible patients up to date for colorectal cancer screening each week (n = 7170 March 15, 2020; n = 7168 November 29, 2020). For reference the lockdown and re-opening stages and when FIT testing could be ordered again have been identified. Lockdown = March 20, 2020, Stage 2 = June 12, 2020, Stage 3 = July 17, 2020, FIT Resumes = August 25, 2020, and Modified Stage 2 = October 13, 2020

Type 2 Diabetes Screening Rates. Shows the mean percentage (percentage screened ± SD) of eligible patients up to date for cervical cancer screening each week (n = 10,897 on March 15, 2020; n = 10,933 on November 29, 2020). For reference the lockdown and re-opening stages have been identified. Lockdown = March 20, 2020, Stage 2 = June 12, 2020, Stage 3 = July 17, 2020, and Modified Stage 2 = October 13, 2020

A line of best fit was generated for each screening test and the slope indicated the weekly rate of change during this period. Cervical cancer screening rates decreased by 0.23% per week (Fig. 1). Colorectal cancer screening rates decreased by 0.25% per week (Fig. 2). Type 2 diabetes screening rates decreased by 0.13% per week (Fig. 3).

The Government of Ontario’s stages of gradual reopening are indicated for reference to demonstrate the impact of re-opening efforts on screening rates (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). For colorectal cancer screening, the date that FIT testing could be ordered was also shown (Fig. 2). None of the re-opening measures reversed the decreased screening trends across the three observed screening tests.

Crude estimates of the preventive care service deficits from baseline screening

The number of patients among the 22,685 active patients at the three clinics requiring screening to return to baseline, low-risk screening rates were determined. A total of 505 (20 to 993; 95% CI) patients would need to have Papanicolaou smear testing (Table 4), 577 (22 to 1133; 95% CI) would need CRC screening (Table 5), and 489 (21 to 951; 95% CI) would need type 2 diabetes screening (Table 6).

Extrapolation of these numbers to Ontario’s population provided a crude estimate of the Ontarians requiring screening to return to pre-COVID-19, low-risk screening rates. Potentially 288,000 Ontarians (11,000 to 565,000; 95% CI) would need Papanicolaou smear testing (Table 4), 326,000 Ontarians (13,000 to 638,000; 95% CI) would need CRC screening (Table 5), and 274,000 Ontarians (13,000 to 535,000; 95% CI) would need T2DM screening (Table 6).

Similarly, extrapolation to the Canadian population provided a crude estimate of Canadians needing screening to return to pre-COVID-19, low-risk screening rates. Potentially 745,000 Canadians (28,000 to 1,467,000; 95% CI) would need Papanicolaou smear testing (Table 4), 860,000 Canadians (35,000 to 1,685,000; 95% CI) would need CRC screening (Table 5), and 715,000 Canadians (34,000 to 1,396,000; 95% CI) would need T2DM screening (Table 6).

Interpretation

This observational cohort study demonstrates that preventive care service delivery was negatively affected by COVID-19 at the study clinics. This trend has not reversed with re-opening measures implemented by the Government of Ontario. This finding is supported by an abrupt decrease in screening volumes across Ontario for CRC and cervical cancer peaking at 91.3 and 92.3% reductions, respectively [2]. These decreased screening volumes were still below baseline levels as of December 2020 [2], which aligns with persistent decrease in screening demonstrated in this study. Here we provide crude estimates, which indicate that hundreds of thousands of Ontarians and Canadians may have delayed or been unable to access preventive care services since March 2020.

According to a review of preventive care services, only cervical cancer screening requires in-person assessments [5]. Therefore, the finding that cervical cancer screening decreased since March 2020 is as expected, because Ministry of Health directives recommended avoiding in-person assessments [21]. However, CRC screening may be offered through virtual care [5]. The observed decrease in CRC screening is not explained by fewer in-person appointments. Instead, both laboratories pausing FIT kit distribution to reserve capacity for COVID-19 testing [10] and the Ministry of Health recommendation to defer non-essential services [21] have likely contributed to decreased CRC screening. This recommendation to defer healthcare services has likely reduced T2DM screening, as screening could be offered through virtual care [5] without restrictions on hemoglobin A1c or fasting blood sugar testing. Similar findings of reduced utilization of healthcare services have been observed through fewer emergency department visits for heart failure [22], stroke [23], and pediatric assessments [24]. Patient and provider clinical priorities may also shift from prevention and screening to management of active problems, like increased demand for mental healthcare services [25]. Therefore, the findings of this study indicate that the reductions in preventive care service delivery are likely multifactorial.

Sustained reductions in preventive care are concerning since screening can detect early disease like cervical cancer, CRC, or T2DM. Accordingly, many cases of early disease are likely going undetected. Delayed diagnoses may have significant consequences as each 4 week delay in CRC treatment could increase mortality rates by 6 to 8% [3]. This is supported by a recent model that predicted prolonged preventive care delays will cause higher cancer mortality and advanced disease at diagnosis [26]. From a health system perspective, delayed cancer diagnoses may significantly increase cancer treatment costs [27]. Prolonged undiagnosed and untreated T2DM is also expected to present problems since untreated T2DM increases the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality [28]. Therefore, strategies to restore preventive care service delivery to pre-COVID-19 levels are essential. As COVID-19 restrictions persist and recur, the multifactorial patient, provider and health system factors impacting preventive care delivery need to be better understood and addressed.

This study has demonstrated that EMR data can be used to determine patients’ preventive care screening statuses. This automated function could be developed for other EMRs to generate monthly preventive care reports for providers [29]. These reports could then be used for targeted preventive care delivery, prioritising in-person visits for those most overdue or needing tests that require in-person assessments. Additionally, point-of-care tools could support opportunistic preventive care delivery during visits for other reasons. The literature supports that digital solutions like EMR reminders [30] combined with active panel management [29, 30] can improve screening rates. However, in order to leverage EMR data to improve preventive care rates, system capacity must be improved as laboratories have only recently restored some capacity for screening test [31].

Another potential strategy has already been implemented by the Government of Ontario to address the surgical backlog, including cancer surgeries [32]. This strategy involves investments in system capacity and providing financial incentives for health service delivery [33]. Directing additional resources upstream to support additional time and planning to restore preventive care services could effectively boost screening rates [34] and maintain early disease detection. This could help mitigate the anticipated increase in cancer mortality, later stage diagnoses [26], and increased health care costs [27]. These resources may also maintain the focus on early detection as large numbers of patients begin seeking care for neglected physical and mental conditions [35].

Limitations

This study extrapolated data based on three clinics in Ottawa, a single urban centre in Ontario, Canada. The data in Table 2 indicates that the study clinic age demographics do not exactly match the Ontario and Canadian populations. As well, differences may exist between urban and rural preventive care service delivery and across Ontario. Lastly, each province is responsible for the local health care service delivery. Therefore, the generalizability could be impaired, and attempts have been made to avoid overstating the results beyond the local clinic. This study also relies on high quality EMR data which may suffer from accuracy, completeness, and consistency issues [36]. These challenges arose when developing the data export. Screening data was not consistently encoded following the same method, therefore multiple exported data points had to be amalgamated to improve data quality. Lastly, the impact of COVID-19 on T2DM screening may be underestimated since a 3 year interval was used despite guidelines recommended 1 to 3 years based on calculated risk scores.

Conclusions

This observational cohort study estimated that hundreds of thousands of Canadians may not have been screened for cervical cancer, CRC, and T2DM according to low-risk screening guidelines. Re-opening initiatives have not reversed the decrease in screening rates. Given the decreased screening, Canadians will likely be facing a surge of later stage cancer and diabetes diagnoses. Therefore, strategies like using EMR data to inform active panel management and directing additional resources to preventive care delivery and testing will be needed to reverse these trends and catchup on the hundreds of thousands of overdue tests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due patient confidentiality and privacy. Filtered data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and review by Bruyère Research Ethics Board.

References

Wang J, Vahid S, Eberg M, Milroy S, Milkovich J, Wright FC, et al. Clearing the surgical backlog caused by COVID-19 in Ontario: a time series modelling study. CMAJ. 2020;192(44):E1347–56. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.201521.

Walker MJ, Meggetto O, Gao J, Espino-Hernández G, Jembere N, Bravo CA, et al. Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organized cancer screening and diagnostic follow-up care in Ontario, Canada: a provincial, population-based study. Prev Med. 2021;151:106586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106586.

Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, Jalink M, Paulin GA, Harvey-Jones E, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4087.

Ontario Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Guidance: Primary Care Providers in a Community Setting. Version 7. 2020.

Dickinson JA, Thériault G, Singh H, Szafran O, Grad R. Rethinking screening during and after COVID-19: Should things ever be the same again? Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(8):571–5.

Waterloo Wellington Regional Cancer Program. Cancer Screening – Gradual Phased Resumption Summary. 2020. Available from: http://www.cancercare4primarycare.com/uploads/Common/cancer%20screening%20-%20gradual%20phased%20resumption%20summary%20_FINAL.pdf

Cancer Care Program service reintroductions | Nova Scotia Health Authority [Internet]. Available from: http://www.nshealth.ca/service-reintroduction-notices/cancer-care-program-service-reintroductions. Accessed 28 Dec 2020.

COVID-19 and Cancer Screening [Internet]. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/health-professionals/covid-19-and-cancer-screening. Accessed 28 Dec 2020.

COVID-19 - Information for Breast Screening Clients [Internet]. Available from: http://www.saskcancer.ca/screening-article/covid-19-information-for-breast-screening-clients. Accessed 28 Dec 2020.

Ontario Health. COVID-19 cancer screening tip sheet for primary care providers: 15 – Guidance for primary care providers resuming breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.afhto.ca/sites/default/files/2020-07/COVID-19%20Tip%20Sheet%20%2315-%20Guidance%20for%20Primary%20Care%20Providers%20Resuming%20Cancer%20Screening.pdf. Accessed 21 Dec 2021.

Ehrenstein V, Kharrazi H, Lehmann H, Taylor CO. Obtaining Data From Electronic Health Records [Internet]. Tools and Technologies for Registry Interoperability, Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide, 3rd Edition, Addendum 2: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2019. [cited 2020 Dec 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551878/

Telus Health. PS Suite User Manual. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 8]. Available from: https://help.pssuiteemr.com/5.15/on/en/Content/01_Introduction/Download_PDFs.htm

PS Suite EMR | TELUS Health [Internet]. TELUS. Available from: https://www.telus.com/en/health/health-professionals/clinics/ps-suite. Accessed 8 Jan 2020.

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | Cervical Cancer (2013). [cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/cervical-cancer/

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | Colorectal Cancer (2016). [cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/colorectal-cancer/

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | Diabetes, Type 2 (2012). [cited 2020 Jan 22]. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/type-2-diabetes/

Ekoe J-M, Goldenberg R, Katz P. Screening for diabetes in adults. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42:S16–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.004.

CANRISK Tools - English [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.pharmacists.ca/education-practice-resources/patient-care/diabetes-practice-tools-and-resources/canrisk-tools/

Reopening Ontario in stages [Internet]. Ontario.ca. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 5]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/reopening-ontario-stages

Government of Canada SC. Census Profile, 2016 Census - Ontario [Province] and Canada [Country]. 2017 [cited 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=35&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=35&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=3

Ontario Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Directive #2 for Health Care Providers (Regulated Health Professionals or Persons who operate a Group Practice of Regulated Health Professionals). 2020.

Frankfurter C, Buchan TA, Kobulnik J, Lee DS, Luk A, McDonald M, et al. Reduced rate of hospital presentations for heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic in Toronto, Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(10):1680–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.07.006.

Bres Bullrich M, Fridman S, Mandzia JL, Mai LM, Khaw A, Vargas Gonzalez JC, et al. COVID-19: stroke admissions, emergency department visits, and prevention clinic referrals. Can J Neurol Sci J Can Sci Neurol. 2020;47(5):693–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2020.101.

Goldman RD, Grafstein E, Barclay N, Irvine MA, Portales-Casamar E. Paediatric patients seen in 18 emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2020;37(12):773–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-210273.

Vigo D, Patten S, Pajer K, Krausz M, Taylor S, Rush B, et al. Mental Health of communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatr. 2020;65(10):681–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720926676.

Mainprize BJHYJG, Yaffe MJ, Ruan Y, Poirier AE, Coldman A, Nadeau C, et al. The impact of episodic screening interruption: COVID-19 and population-based cancer screening in Canada. J Med Screen. 2020; [cited 2020 Dec 28]; Available from: https://journals-sagepub-com.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/doi/full/10.1177/0969141320974711.

Reyes C, Engel-Nitz NM, DaCosta BS, Ravelo A, Ogale S, Bancroft T, et al. Cost of disease progression in patients with metastatic breast, lung, and colorectal Cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(9):1209–18. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0018.

Flores-Le Roux JA, Comin J, Pedro-Botet J, Benaiges D, Puig-de Dou J, Chillarón JJ, et al. Seven-year mortality in heart failure patients with undiagnosed diabetes: an observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-10-39.

Marx R, Tse WM, Golden L, Johnson EC. Increasing colorectal Cancer screening at community-based primary care clinics in San Francisco. J Public Health Manag Pract JPHMP. 2016;22(5):466–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000275.

Loo TS, Davis RB, Lipsitz LA, Irish J, Bates CK, Agarwal K, et al. Electronic medical record reminders and panel management to improve primary care of elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1552–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.394.

Toronto Central Regional Cancer Program. COVID-19: Cancer Screening Update. 2020. Available from: https://www.trcp.ca/en/Documents/COVID-19_Guidance_for_Primary_Care_Providers_Resuming_Cancer_Screening.pdf

Ontario Office of the Premier. Ontario Investing $741 Million to Reduce Surgeries Backlog and Expand Access to Care [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/58557/ontario-investing-741-million-to-reduce-surgeries-backlog-and-expand-access-to-care. Accessed 28 Dec 2020.

Government of Ontario M of H and L-TC. OHIP INFOBulletin. Temporary Payment Criteria for After Hours Procedure Premiums [Internet]. Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; [cited 2020 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/redux/bul201110.aspx

Kicinger IM, Cuellar A, Helmchen LA, Gimm G, Want J, Kells BJ, et al. Quality of care and preventive screening use in the CareFirst patient-centered medical home program. J Healthc Qual Off Publ Natl Assoc Healthc Qual. 2019;41(6):339–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000169.

Williams R, Jenkins DA, Ashcroft DM, Brown B, Campbell S, Carr MJ, et al. Diagnosis of physical and mental health conditions in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(10):e543–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30201-2.

Feder SL. Data quality in electronic Health records research: quality domains and assessment methods. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40(5):753–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916689084.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Tim Ramsay at the Ottawa Methods Centre for critical review of the methodology.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) through the CGS-M scholarship #: 201912GSM. This grant provided salary support for SL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, including development of the scripts that performed the analysis. Both SL and SJ contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted and revised the final manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Bruyère Research Ethics Board at Bruyère Hospital in Ottawa, Ontario. REB Ethics Number: #M16–20-045.

Consent for publication

Patient consent was not required as was determined by the Bruyère Research Ethics Board at Bruyère Hospital in Ottawa, Ontario. REB Ethics Number: #M16–20-045. All required privacy and security measures were followed.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Laing, S., Johnston, S. Estimated impact of COVID-19 on preventive care service delivery: an observational cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 1107 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07131-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07131-7