Abstract

Background

Truly patient-centred care needs to be aligned with what patients consider important, and is highly desirable in the first 24 h of an acute admission, as many decisions are made during this period. However, there is limited knowledge on what matters most to patients in this phase of their hospital stay. The objective of this study was to identify what mattered most to patients in acute care and to assess the patient perspective as to whether their treating doctors were aware of this.

Methods

This was a large-scale, qualitative, flash mob study, conducted simultaneously in sixty-six hospitals in seven countries, starting November 14th 2018, ending 50 h later. One thousand eight hundred fifty adults in the first 24 h of an acute medical admission were interviewed on what mattered most to them, why this mattered and whether they felt the treating doctor was aware of this.

Results

The most reported answers to “what matters most (and why)?” were ‘getting better or being in good health’ (why: to be with family/friends or pick-up life again), ‘getting home’ (why: more comfortable at home or to take care of someone) and ‘having a diagnosis’ (why: to feel less anxious or insecure). Of all patients, 51.9% felt the treating doctor did not know what mattered most to them.

Conclusions

The priorities for acutely admitted patients were ostensibly disease- and care-oriented and thus in line with the hospitals’ own priorities. However, answers to why these were important were diverse, more personal, and often related to psychological well-being and relations. A large group of patients felt their treating doctor did not know what mattered most to them. Explicitly asking patients what is important and why, could help healthcare professionals to get to know the person behind the patient, which is essential in delivering patient-centred care.

Trial registration

NTR (Netherlands Trial Register) NTR7538.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

To deliver patient-centred care, it is important to know what matters to every patient. Nevertheless, our study showed that a large group of patients felt that their treating physician did not know what mattered most to them at that moment.

-

Although the majority of patients initially indicated disease- and care-related matters to be most important, they shared diverse personal stories when asked about their motivations and why these were important. These stories show the person behind the patient.

-

The questions “What matters most to you?” and especially “why does this matters most?” are questions that can provide healthcare workers with personal information about the patients’ preferences, needs, goals, values and emotions, necessary to deliver patient-centred care.

Introduction

Effective patient-doctor communication and patient involvement can lead to increased patient satisfaction, better health outcomes, and is essential to the delivery of patient-centred care [1, 2]. However, with growing worldwide pressure on acute healthcare systems and the resultant limited time available per patient [3, 4], it is increasingly challenging for healthcare providers to have comprehensive conversations with patients. As a result, they may not have adequate psychological and emotional insights into the patients’ priorities [5, 6]. Research shows that many clinicians’ conversations are about patients and not with them [7], and that patients are seen as their disease(s) rather than as individuals [6].

The goal of patient-centred care is to customize care to the individual patient, taking into consideration their preferences, needs and values. To achieve this, Barry and Edgman-Levitan (2012) proposed asking the patient “what matters to you?”, in addition to “what is the matter?” [8]. This topic has received increasing attention over the years, and an annual international “What Matters to you?” day was launched in 2016 to promote meaningful conversations between healthcare providers and patients [9]. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) states that the “what matters to you?” question is a quick, simple, but yet profound way to start deep and personal conversations with patients [10]. It encompasses discussing the patients’ priorities and values alongside potentially revealing unanswered questions, which could provide input for a personalized care plan [11].

Much research has been conducted to investigate the priorities and preferences of patients with specific diagnoses [12,13,14], treated in the Emergency Department [15] or in chronic disease programs [16,17,18,19,20], which has resulted in the development of multiple frameworks (e.g. Lim [21] and Picker experience [22]). However, little is known about what is most important to the heterogeneous group of patients (with regards to morbidity, basic characteristics, culture, health and socio-economic status) during the acute phase of a hospital admission. The first 24 h of an acute admission will often determine the course of the hospital stay. In this phase many diagnostic tests are carried out, care plans are created, and key decisions made. It is crucial that during this time-period the priorities of the patient are clear to the healthcare team [12]. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to identify and categorize what matters most to the diverse group of patients in the first 24 h of an admission.

Not only must doctors converse with patients, it is important that patients feel that they have been listened to, have been understood, and that their concerns will be considered and addressed [5, 8, 23]. As such, the secondary objective of this study was to assess the patient perspective on whether they felt their doctor knew what mattered most to them.

Methods

Study design and setting

A large-scale qualitative international study was conducted using the flash mob research design [24, 25]. The flash mob research design is based on the concept of flash mobs, where groups of people suddenly meet in a public place, briefly perform a specific act and then quickly disappear. This allowed us to collect structured qualitative data from a large number of patients within a short time-period. To get an overview of what matters most to patients in a wider socio-cultural context, the study was conducted across a wide range of countries, regions and cultures.

The study started on November 14th, 2018 at 10 AM local time, and ended 50 h later on November 16th, 12 PM local time. Patients in 66 hospitals were recruited simultaneously in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, Switzerland, Hong Kong and Singapore. Data were collected in acute medical units (AMUs, short stay departments [26]) and other medical wards (i.e. observation units, cardiology, geriatrics, gastroenterology, haematology, internal medicine, nephrology, neurology, oncology, pulmonary medicine and rheumatology).

The Executive Committee of the Medical Ethics Review Committee of VU University Medical Center (IRB00002991) reviewed the research proposal, approved the project and decided that the Medical Research involving Human Subjects Act did not apply (reference No. 2018.318). In all other countries, approval of national ethics committees and executive boards was sought in line with local research policies.

The acute medicine research team of Amsterdam University Medical Center (located at VUmc, the Netherlands) coordinated the project. Collaborators from the Safer@Home research consortium were involved in the design of the study and acted as coordinating researchers, responsible for the recruitment of hospitals in their country [27].

Research team and responsibilities

The coordinating investigator in each country was responsible for translating the English datasheet into the local language (using forward- and backward translation, according to the ISPOR guidelines [28]) and translating the open text answers to English (with a forward- and backward translation of a 10% convenience sample).

Every hospital had one ambassador responsible for appointing interviewers for data collection, recruitment of patients and entering the data into the digitalized secured database (Castor EDC). Interviewers were physicians, (research) nurses, medical students, or psychologists, all trained in communication skills.

Recruitment of patients

Consecutive sampling was used to recruit a broad range of participants which would be largely representative of the acute patient population. All patients were 18 years or older, were unplanned admitted to hospital in the previous 24 h and able to give informed consent. Patients presenting with surgical, trauma and obstetric conditions and patients unable to give informed consent, as judged by the medical team, were excluded. Patients were asked for oral or written informed consent, depending on national research policies. Patients were approached face-to-face and assured that their decision to participate or not participate would have no consequences for their care.

Questionnaire

In the questionnaire we used the classic ‘what matters to you?’ question [8, 10, 29, 30]. After a pilot study in ten patients, we found that adding a probing question (‘why is this important to you?’) was necessary to grasp the full concept. The data from these patients were used purely for the purpose of pilot testing the questionnaire, and not included in the data analysis.

The question ‘does your treating doctor in the hospital know what matters to you most?’ was added to find out about the patients’ perception regarding this subject. The questionnaire was complemented by questions concerning basic characteristics, living conditions, social and work situation. To find out how patients interpreted all questions, we used a cognitive interviewing style [31] during the pilot (e.g. by asking their opinion about the content and relevance of questions).

All questionnaires were available in each country’s local language.

Data collection and privacy

Interviewers solely introduced themselves by name and had no prior relationship with the patients. Each interview took approximately 5 min. Data were collected at the bedside, and either entered directly into the digital database or transcribed from a paper datasheet, without the use of audio or visual recordings. Patients’ responses were not recorded verbatim, but paraphrased by the interviewer. Paraphrased answers were not returned to patients for review.

All interviewers had their own personal Castor EDC account for data input and were trained by both video tutorials and written instructions. Measures and warnings were built into the database to minimize the potential for errors. Interviewers transcribed the patient’s answers into the Castor EDC database. All records were labelled with an individual number. The key list with record numbers could only be accessed by the local coordinating researcher. No directly identifiable data were entered into the database.

Data translation and development of the conceptual coding framework for content analysis

Danish, Swiss and Dutch data were translated to English; back-translation was conducted on 10% convenience samples and checked by independent assessors. No essential differences between the original data and back-translations were found.

To analyse the large number of open-text answers, a framework needed to be developed that could be used for coding both the answers to the ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’ questions.

An inductive approach of content analysis was used to identify categories and sub-categories in the data, leading to the development of a conceptual framework on what matters most to acutely admitted patients and why [32]. This framework was developed through five phases (using open coding, grouping, categorization and abstraction throughout each phase [32]), by four researchers (two medical doctors and two psychologists). A detailed description of the process can be found in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material.

Coding and data analysis

All 3700 answers (100% of data) to the ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’ questions were independently coded by both a medical doctor (EE or MK) and a psychologist (BS or HM), using the developed framework. Multiple categories could be assigned to one answer, without hierarchy. When there were discrepancies in assigned categories, an extensive consensus procedure followed (resulting in 100% agreement regarding the final categories). Composition of teams rotated to account for differences in interpretation (i.e. EE + BS, EE + HM, MK + BS, MK + HM).

As the qualitative data were large-scale, the frequency of categories was analysed and visualized in word clouds. Moreover, we analysed the combined occurrence of answers to the ‘what matters most to you?’ and ‘why?’ questions to identify patterns. We did this by counting which combinations of categories occurred most between the ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’ question (for example; patients often wanted to go home because they missed family members). Finally, we performed multiple subgroup analyses.

Coding was performed in Excel (Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2016). Word counts and word clouds were generated using Atlas.ti8 (Atlas.ti Scientific Software GmbH). Descriptive statistics were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 24 (SPSS Inc).

Results

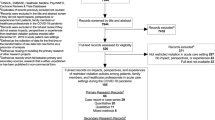

During the inclusion period, 2798 patients had been admitted to the participating units for 24 h or less, and were therefore eligible for inclusion. However, 866 (31%) patients were excluded because they were not able to give informed consent or were unwilling or unable to participate (Fig. 1). Eighty-two patients were interviewed but later excluded because they had been admitted for more than 24 h prior to their questionnaire. Therefore, the interviews of 1850 (66%) acutely admitted patients were analysed. Figure 1 provides an overview of the inclusion process and numbers of included patients per country. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics of the included patients.

What matters most to patients and why?

The coding framework included twelve categories (health, getting home, symptom relief, functioning, medical issues, hospital experience, patient values, reassurance, possessions, emotions, urgency, and other). These categories were divided into 38 sub-categories (e.g. ‘symptom relief’ was divided into pain, dyspnoea, fatigue, nausea). Table S1 in the Supplementary Material shows the categories and sub-categories, illustrated by explanations and quotes.

To most answers, two to four categories were assigned. Of all patients, 29.6% answered that being in good health or getting better was most important at that moment, 17.4% said they wanted to go home and 16.1% considered knowing the diagnosis was most important. These categories were assigned notably more often than others (see Fig. 2 and Table S2 in the Supplementary Material).

Compared to the answers to the ‘what matters most?’ question, the answers to ‘why does this matters most?’ showed a broader range of categories, with no clear top three (see Fig. 3). Health was mentioned less often as an underlying reason compared to the ′what matters′ question (Supplementary Material: Table S3). Many issues were mentioned by comparable numbers of patients (e.g. family and friends (11.8%), psychological functioning (11.2%), fear, anxiety and insecurity (10.4%)).

Combined occurrence of what matters and why

Underlying reasons for ‘what mattered most?’ were given when asked ‘why this mattered most?’. Analysis of answers to the ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’ questions, revealed combinations of answers that occurred frequently together. Illustrations of apparent combinations observed in the top three ‘what matters most?’ categories are shown below.

Getting better

Most patients wanted to get better to be reunited with their loved ones (usually partner or children, sometimes friends or other family members): “I miss my two-year-old son and sense that he is missing me a lot too. I want to get better so I can take care of my son and to have the energy to do fun things with him.” (Female, age-group 31–35 years, The Netherlands), “To get rid of my alcohol problem. It is important because it is destroying me and my family.” (F, 56-60Y, Denmark), “It’s important for me to recover as my children and grandchildren depend on me for money.” (M, 61-65Y, United Kingdom) Other patients wanted to get better to get back to their normal life: “That I will be able to do everything I feel like again.” (M, 71-75Y, The Netherlands).

Getting home

Most patients mentioned the familiarity of the home situation, their role as an informal caregiver or relationships as the main reason to strive for a return to home. Examples include: “I feel better at home, having your own stuff around.” (M, 71-75Y, The Netherlands), “At home I feel most comfortable, they have no dark beer here.” (M, 86-90Y, The Netherlands), “To get home to my wife and our 3-year old daughter. My wife is expecting, I just cannot bear the thought of her giving birth without me.” (M, 41-45Y, Denmark), “My husband is 80. It is more difficult for him to visit me in hospital now.” (F, 67-80Y, United kingdom), “Wish to get home to my daughter- in-law’s 50th birthday on Friday.” (M, 66-70Y, Denmark).

Getting a diagnosis

The wish for an established diagnosis was most often expressed in combination with fear and insecurity. Patients wanted reassurance and felt having a diagnosis would make them function better psychologically. “To know what is wrong for peace of mind.” (M, 46-50Y, The Netherlands), “I want to be able to do my own research or reading about the diagnosis.” (F, 66-70Y, United Kingdom), “It is unsafe to be sent home without clarification.” (F, 31-35Y, Denmark), “That I get my diabetes management optimised, even though I’m admitted with a COPD exacerbation. I’m scared that my legs will need amputating and then I can’t live in my apartment and keep my 11-year-old dog anymore.” (M, 51-55Y, Denmark), “To find peace of mind and closure. I’m afraid of Alzheimer’s and aging, it is affecting work.” (F, 56-60Y, Ireland).

Patient perspective: does your doctor know?

More than half of all patients (51.9%) felt their treating doctor did not know what mattered to them most. Of this group, some patients (21.3%) reported to not have seen a doctor yet. Other reasons included “it did not come up in the conversation”, “the doctor does not need to know”, “there was no chance or no reason to tell”, or “the doctor did not listen” (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis

Women more frequently considered the way that they were approached by healthcare staff (e.g. a kind approach, personal attention, honesty, openness, feeling supported, being treated with respect and dignity) as most important (12.2% of women, 5.6% of men). We found no major differences in both ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’ between different age groups (18–40, 41–70, 71+), patients with different length of stay (≤6 and > 6 h), and those who felt that the doctor knew (or not) (Supplementary Material: Table S4). In Asian countries we found a relatively high percentage of patients mentioning getting better/ good health as being most important (47.8–65.8% in Asian countries, 18.3–39.0% in Western countries). Patients in Singapore mentioned their work as the reason why things mattered more often than patients in other countries (17.1% and ≤ 7.2% respectively) (Supplementary Material: Table S5).

Discussion

In this study 1850 patients admitted acutely to sixty-six hospitals in seven countries were asked what mattered most to them and why. Irrespective of the country, disease- and care-related issues were predominant in reply to the ‘what matters most?’ question: getting better, knowing the diagnosis and being able to go home. This is in line with the main function of an acute hospital admission and the motivation and focus of clinicians: diagnosing, treating and timely discharge [33]. However, when asked why they answered the way they did, patients provided more personal answers, often mentioning relationships and psychological well-being. Whereas many patients mentioned the same issues to the question ‘what matters most to you?’, the underlying reasons as to ‘why is this important?’ differed significantly from patient to patient. This probably reflects the heterogeneity of acutely admitted patients with regards to morbidity, baseline characteristics, culture, health, socio-economic status and phases of their lives. It demonstrates the challenges of providing patient-centred care without discussing what is most important with each individual patient.

Although certain combinations of what matters? and why? were more common than others, and some categories were mentioned more frequently within certain subgroups of patients, individual priorities are not predictable. Knowing what matters to each individual patient is key [34,35,36] because, as our data shows, it is a reflection of personal goals and preferences.

A large group of patients felt the treating doctor was unaware of what mattered most to them, partly because it did not come up during the consultation. Doctor-patient communication is crucial to the doctor-patient relationship [37], and essential in delivering high quality care, since the priorities of doctors and patients can differ [38]. It is conceivable that doctors focus mainly on diagnosing and treating the underlying medical condition. However, since the data represents the perception of patients, it is also possible that doctors do know what matters most, without the patient consciously realizing this. As the feeling of being heard and understood is essential in the process of patient-centred decision-making [39], it is recommended to have explicit conversations about what matters most and why, even if the doctor believes they already know this. Feeling heard and understood is known to alleviate suffering [40, 41], reinforce dignity [42, 43] and is one of the key factors in patient reported quality of care [44, 45]. It could help making patients feel that doctors see them as a person instead of a disease to be treated.

In healthcare settings with limited time per patient, these two simple questions (‘what matters most to you?’ and ‘why?’) may be a feasible way to quickly get to know the person behind the patient. The conversation will give insight into the personal situation of the patient, stimulate patient involvement and ultimately could facilitate more patient-centred care [46]. Having these conversations early in the admission will help set the agenda and design a tailored care plan [8, 47, 48].

Strengths and limitations

The flash mob research design enabled us to include many patients within a short timeframe in seven different countries and 66 hospitals, across cities, towns and rural areas. It provided data from a large heterogeneous patient population representative of the wide diversity of acutely admitted patients. There were no missing data in the main questions. The scale of the study has enabled us to create awareness among many healthcare providers and patients. Lastly, we developed a new conceptual framework based on multiple perspectives using an iterative process. Answers were coded by both a medical doctor and psychologist, which ensured capturing the medical as well as the psychological component. The framework is comprehensive and suitable for the broad concept of ‘what matters most?’ and ‘why?’. Therefore, we believe the framework will be suitable for use in other patient groups and settings as well.

The results of our study need to be interpreted in the light of a few limitations. Firstly, answers from patients might have been paraphrased, which may have simplified patient answers. Secondly, due to the large number of interviewers, it is possible that there were differences in interview styles. However, as there were only two, highly standardized main questions, we believe this would not have had a significant influence on our results.

Future research might focus on how ‘what matters most’ to patients might change over the course of a hospital admission. Although no large differences were found between patients that had only spent up to 6 h in hospital and those in hospital from six to 24 h, we do not know whether the findings are representative for what matters most to patients in later phases of their admission. Furthermore, it would be interesting to conduct a study where both the patient, the doctor and all other professionals in the healthcare team are interviewed about what matters most to the patient in order to compare and align their views.

Conclusions

Patients most frequently mentioned the importance of getting better, having a diagnosis and going home in the first 24 h of an admission. ‘Why’ this matters is strongly determined by each individual patient and often goes well beyond the medical targets of healthcare professionals. When asking for the patient perspective, a large group of patients felt the treating doctor did not know what mattered to them. Explicitly asking ‘what matters most?’ and especially ‘why?’, may help the healthcare team to obtain a more holistic picture and to see the person behind the patient. Having conversations regarding what is important to the patient should assist with the design of a personalized care plan and will help the patient to feel heard, which positively effects the patient satisfaction, health outcomes and the overall quality of care.

Availability of data and materials

The anonymized dataset is available on reasonable request after approval of the corresponding author.

Change history

18 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06580-4

Abbreviations

- NTR:

-

Netherlands Trial Register

- AMUs:

-

Acute medical units

References

Kebede S. Ask patients “What matters to you?” rather than “What’s the matter?”. BMJ. 2016;354:i4045.

Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, Knowles SB, Lavori PW, Lapidus J, et al. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):566–77. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200906-0907OC.

Simmons S, Sharp B, Fowler J, Fowkes H, Paz-Arabo P, Dilt-Skaggs MK, et al. Mind the (knowledge) gap: the effect of a communication instrument on emergency department patients’ comprehension of and satisfaction with care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(2):257–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.020.

Sustersic M, Gauchet A, Kernou A, Gibert C, Foote A, Vermorel C, et al. A scale assessing doctor-patient communication in a context of acute conditions based on a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192306.

Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient–doctor communication during consultation: a narrative literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):641–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01065.x.

Muntlin A, Carlsson M, Gunningberg L. Barriers to change hindering quality improvement: the reality of emergency care. J Emerg Nurs. 2010;36(4):317–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2009.09.003.

Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient's agenda: have we improved? Jama. 1999;281(3):283–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.3.283.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1109283.

website what matters to you [cited 2019 12–07]. Available from: https://www.whatmatterstoyou.scot/.

Improvement IfH. The Power of Four Words: “What Matters to You?” [Available from: http://www.ihi.org/Topics/WhatMatters/Pages/default.aspx.

Rutherford PA. Reliably addressing “what matters” through a quality Improvement process. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(1):20–2. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.20-22.

Osborne TR, Ramsenthaler C, de Wolf-Linder S, Schey SA, Siegert RJ, Edmonds PM, et al. Understanding what matters most to people with multiple myeloma: a qualitative study of views on quality of life. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):496. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-496.

Guzman J, Gomez-Ramirez O, Jurencak R, Shiff NJ, Berard RA, Duffy CM, et al. What matters most for patients, parents, and clinicians in the course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis? A qualitative study. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(11):2260–9. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131536.

Karel MJ, Mulligan EA, Walder A, Martin LA, Moye J, Naik AD. Valued life abilities among veteran cancer survivors. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):679–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12343.

Kremers MNT, Zaalberg T, van den Ende ES, van Beneden M, Holleman F, Nanayakkara PWB, et al. Patient's perspective on improving the quality of acute medical care: determining patient reported outcomes. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(3):e000736. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000736.

Bos N, Sturms LM, Stellato RK, Schrijvers AJ, van Stel HF. The consumer quality index in an accident and emergency department: internal consistency, validity and discriminative capacity. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1426–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12123.

Jonathan D, Sonis ELA, Castagna A, White B. A conceptual model for emergency department patient experience. J Patient Exp. 2018;6(3):173.

Male L, Noble A, Atkinson J, Marson T. Measuring patient experience: a systematic review to evaluate psychometric properties of patient reported experience measures (PREMs) for emergency care service provision. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(3):314–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx027.

Vaillancourt S, Seaton MB, Schull MJ, Cheng AHY, Beaton DE, Laupacis A, et al. Patients’ perspectives on outcomes of care after discharge from the emergency department: a qualitative study. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):648–58.e2.

Olthuis G, Prins C, Smits MJ, van de Pas H, Bierens J, Baart A. Matters of concern: a qualitative study of emergency care from the perspective of patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(3):311–9.e2.

Lim CY, Berry ABL, Hirsch T, Hartzler AL, Wagner EH, Ludman EJ, et al. Understanding what is Most important to individuals with multiple chronic conditions: a qualitative study of Patients’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1278–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4154-3.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, Richards N, Chandola T. Patients’ experiences and satisfaction with health care: results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Qual Safety Health Care. 2002;11(4):335–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.11.4.335.

Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

Wesselius HM, van den Ende ES, Alsma J, Ter Maaten JC, Schuit SCE, Stassen PM, et al. Quality and quantity of sleep and factors associated with sleep disturbance in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1201–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2669.

Alsma J, van Saase J, Nanayakkara PWB, Schouten W, Baten A, Bauer MP, et al. The power of flash mob research: conducting a Nationwide observational clinical study on capillary refill time in a single day. Chest. 2017;151(5):1106–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.035.

Atkin C, Knight T, Subbe C, Holland M, Cooksley T, Lasserson D. Acute care service performance during winter: report from the winter SAMBA 2020 national audit of acute care. Acute Med. 2020;19(4):220–9.

Website Safer@Home [Available from: http://www.saferathome.org/.

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x.

Lang D, Hoey C, Whelan M, Price G. The introduction of “what matters to you”: a quality improvement initiative to enhance compassionate person-centered care in hospitals in Ireland. Int J Integr Care. 2017;17(5):445. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.3765.

Doyle C, Reed J, Woodcock T, Bell D. Understanding what matters to patients - identifying key patients’ perceptions of quality. JRSM Short Rep. 2010;1(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1258/shorts.2009.100028.

Aschermann E, Mantwill M, Köhnken G. An independent replication of the effectiveness of the cognitive interview. Appl Cogn Psychol. 1991;5(6):489–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350050604.

Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

Deruaz-Luyet A, N'Goran AA, Pasquier J, Burnand B, Bodenmann P, Zechmann S, et al. Multimorbidity: can general practitioners identify the health conditions most important to their patients? Results from a national cross-sectional study in Switzerland. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0757-y.

Naik AD. On the road to patient centeredness. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):218–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1229.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–3. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1239.

Hanyok LA, Hellmann DB, Rand C, Ziegelstein RC. Practicing patient-centered care: the questions clinically excellent physicians use to get to know their patients as individuals. Patient. 2012;5(3):141–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262487.

Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. Jama. 1992;267(16):2221–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480160079038.

Lee CN, Hultman CS, Sepucha K. Do patients and providers agree about the most important facts and goals for breast reconstruction decisions? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):563–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c01279.

Elwyn G, Lloyd A, May C, van der Weijden T, Stiggelbout A, Edwards A, et al. Collaborative deliberation: a model for patient care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(2):158–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.027.

Cassell EJ. Diagnosing suffering: a perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):531–4. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00009.

Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(11):639–45. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198203183061104.

Houmann LJ, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. A prospective evaluation of dignity therapy in advanced cancer patients admitted to palliative care. Palliat Med. 2014;28(5):448–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313514883.

Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, Thompson G, Dufault B, Harlos M. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(6):974–80 e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.291.

Ingersoll LT, Saeed F, Ladwig S, Norton SA, Anderson W, Alexander SC, et al. Feeling heard and understood in the hospital environment: benchmarking communication quality among patients with advanced Cancer before and after palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(2):239–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.04.013.

Gramling R, Stanek S, Ladwig S, Gajary-Coots E, Cimino J, Anderson W, et al. Feeling heard and understood: a patient-reported quality measure for the inpatient palliative care setting. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):150–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.018.

Leavitt M. Medscape's response to the Institute of Medicine Report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Medscape Gen Med. 2001;3(2):2.

CCI. The new agenda: patient-centered strategies for the exam room. 2016.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6.

Flash mob website SAFER@HOME [Available from: http://www.flashmobsite.com/.

Acknowledgements

The study was initiated and conducted by a collaboration of acute and emergency physicians and psychologists from several countries (Safer@Home consortium) [49].

We would like to thank all participating patients and healthcare professionals. We especially thank the local coordinators of all participating centres listed in the Supplementary Material.

Local collaborators

Vibe Maria Laden Nielsen, Aalborg University Hospital and Aalborg University, DK; Karen Vestergaard Andersen, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark; Hanne Nygaard, Bispebjerg Hospital, Denmark; Kasper Karmark Iversen, Herlev Hospital, Denmark; Martin Schultz, Herlev Hospital, Denmark; Peter Hallas, Holbæk Hospital, Denmark; Magnus Peter Brammer Kreiberg, Holbæk Hospital, Denmark; Line Emilie Laugesen, Hospital of South West Jutland, Esbjerg, Denmark; Anne Mette Green, Hospital of South West Jutland, Esbjerg, Denmark; Tanja Mose Kristensen, Hospital of South West Jutland, Esbjerg, Denmark; Helene Skjøt-Arkil, Hospital Sønderjylland, Aabenraa, Denmark; Hejdi Gamst-Jensen, Hvidovre Hospital, Denmark; Torbjørn Shields Thomsen, Hvidovre Hospital, Denmark; Camilla Dahl Nielsen, Kolding Hospital, Denmark; Kristian Møller Jensen, Kolding Hospital, Denmark; Søren Nygaard Hansen, Kolding Hospital, Denmark; Marc Ludwig, North Denmark Regional Hospital, Hjørring, Denmark; Henriette Sloth Høg, North Denmark Regional Hospital, Hjørring, Denmark; Dorthe Gaby Bove, North Zealand Hospital Hillerød, Denmark; Vibe Kristine Sommer Mikkelsen, North Zealand Hospital Hillerød, Denmark; Sune Laugesen, Odense University Hospital, Denmark; Nerma Todorovac, Odense University Hospital, Denmark; Stine Nørris Nielsen, Odense University Hospital, Denmark; Poul Petersen, Regional Hospital Herning, Denmark; Hanna Karstensen, Regional Hospital Herning, Denmark; Gitte Boier Tygesen, Regional Hospital Horsens, Denmark; Rasmus Aabling, Regional Hospital Horsens, Denmark; Lone Pedersen, Regional Hospital Randers, Denmark; Sef J L. W. Van Den Beuken, Regional Hospital Viborg, Denmark; Ditte Høgsgaard, Slagelse Hospital, Denmark; Thomas Christophersen, Svendborg Hospital, OUH, Denmark; Christina Smedegaard, Svendborg Hospital, OUH, Denmark; Mette Worsøe, Svendborg Hospital, OUH, Denmark; Marie-Laure M A Bouchy Jacobsson, Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark; Le Elias Lyngholm, Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark; Sara Fonager Lindholm, Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark; JM van Pelt-Sprangers, Admiraal de Ruyter Ziekenhuis, The Netherlands; Ralph K.L. So, Albert Schweitzer Hospital, The Netherlands; Sander Anten, Alrijne Hospital, The Netherlands; Judith van den Besselaar, Alrijne Hospital, The Netherlands; Gerba Buunk, Amphia Hospital, The Netherlands; Lorenzo Romano, Amphia Hospital, The Netherlands; Daan Eeftick Schattenkerk, Amsterdam University Medical Center, location AMC, The Netherlands; Frits Holleman, Amsterdam University Medical Center, location AMC, The Netherlands; Rishi S. Nannan Panday, Amsterdam University Medical Center, location Vu Medical Center, The Netherlands; Sacha C. Rowling, Amsterdam University Medical Center, location Vu Medical Center, The Netherlands; Michiel Schinkel, Amsterdam University Medical Center, location Vu Medical Center, The Netherlands; Sophie van Benthum, Catharina Hospital, The Netherlands; S.J.J. Logtenberg, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, The Netherlands; Esther M.G. Jacobs, Elkerliek Hospital, The Netherlands; Jelmer Alsma, Erasmus University Medical Center, The Netherlands; William Boogers, Erasmus University Medical Center, The Netherlands; Marlies Verhoeff, Gelre Hospitals, Apeldoorn and Zutphen, The Netherlands; Barbara V. van Munster, Gelre Hospitals, Apeldoorn and Zutphen, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands; Emma Gans, Groene Hart Hospital, The Netherlands; Noortje Briët-Schipper, Groene Hart Hospital, The Netherlands; Yotam Raz, Groene Hart Hospital, The Netherlands; Ayesha Lavell, Hospital Amstelland, The Netherlands; Fatima El Morabit, Hospital Amstelland, The Netherlands; Gert-Jan Timmers, Hospital Amstelland, The Netherlands; Ad Dees, Ikazia Hospital, The Netherlands; Ginette Carels, Ikazia Hospital, The Netherlands; Berit Snijer, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, The Netherlands; Anne Floor Heitz, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands; Pim A.J. Keurlings, Maas Hospital Pantein, The Netherlands; Susan Deenen, Maas Hospital Pantein, The Netherlands; Patricia M. Stassen, Maastricht University Medical Center, The Netherlands; Hajar Kabboue, Máxima MC, The Netherlands; Ineke Schouten, OLVG location East, The Netherlands; C.E.H. Siegert, OLVG location West, The Netherlands; Jacobien J. Hoogerwerf, Radboud University Medical Center, The Netherlands; Lianne de Kleijn, Radboud University Medical Center, The Netherlands; Frank H. Bosch, Rijnstate Hospital, The Netherlands; Annebel Govers, Sint Franciscus Gasthuis, The Netherlands; Bianca van den Corput, Sint Franciscus Gasthuis, The Netherlands; Susan Deenen, St. Anna Zorggroep, Geldrop/Eindhoven, The Netherlands; H.S. Noordzij-Nooteboom, The Van Weel-Bethesda Hospital ,The Netherlands; M.J. Dekkers, The Van Weel-Bethesda Hospital, The Netherlands; Annemarie van den Berg, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands; Jan C. ter Maaten, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands; Dennis G. Barten, VieCuri Medical Center, The Netherlands; VieCuri Medical Center, Tessel Zaalberg, The Netherlands; John Soong, National University Hospital, Singapore; Norshima Nashi, National University Hospital, Singapore; Louise S van Galen, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; Lim Wan Tin, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; Tharmmambal Balakrishnan, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; Siti Khadijah Binte Zainuddin, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; Christian H Nickel, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland; Victoria Siegrist, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland; Fraz Mir, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals, United Kingdom; Channa Vasanth Nadarajah, Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital, Hampshire Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom; Aled Lewis, Glan Clwyd Hospital - NHS Direct Wales, United Kingdom; David Ward, Hinchingbrooke Hospital, North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; C Weerasekera, Hull Royal Infirmary, United Kingdom; Thandar Soe, James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; Thomas Cozens, Royal Gwent Hospital, United Kingdom; Joanne McDonald, Salford Royal Hospital NHS FT, United Kingdom; Mark Holland, Salford Royal Hospital NHS FT, United Kingdom; Andrew Down, Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, United Kingdom; Immo Weichert, Ipswich Hospital, East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Foundation Trust (ESNEFT), United Kingdom; Harith Altemimi, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, King's Lynn. NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom; Tim Cooksley, University Hospital of South Manchester, United Kingdom; A Seccombe, University Hospitals Birmingham, United Kingdom; Chris P Subbe, Ysbyty Gwynedd Hospital, United Kingdom; Ben Lovell, University College London Hospitals, United Kingdom; Colin Graham, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Ronson Lo, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Ling Leung, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Rachel M Kidney, St. James’s Hospital, Ireland.

Transparency

The lead authors affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned and registered have been explained.

Funding

There were no funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

EE and BS contributed equally to this work. MB, CHN, PN jointly supervised this work. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author (PN) attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. Concept and design: EE; BS; MK; TC; CS; IW; LG; HH; JK; JA; EC; VS; CG; LLY; LL; FM; RK; HM; MB; CHN; PN. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: EE; BS; MK; HM; PN. Drafting of the manuscript: EE; BS; MK; HM; PN. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: EE; BS; MK; HM; PN. Obtained funding: None. Administrative, technical, or material support: PN. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Executive Committee of the Medical Ethics Review Committee of VU University Medical Center (IRB00002991) reviewed the research proposal, approved the project and decided that the Medical Research involving Human Subjects Act did not apply (reference No. 2018.318). In all other countries, approval of national ethics committees and executive boards was sought in line with local research policies. All protocols are carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All patients provided oral or written informed consent, depending on national research policies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The author Ling Yan LEUNG’s name has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Developmental process of framework. Table S1. Framework for coding. Table S2. Top ten answers to the question ‘what matters most’. Table S3. Top ten answers to the question ‘why is this important’. Table S4. Differences in what matters and why between sex, age groups, length of stay and if patients feel the doctor knows what matters or not. Table S5. Differences in what matters and why to patients between countries. List of local collaborators.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Ende, E.S., Schouten, B., Kremers, M.N.T. et al. Understanding what matters most to patients in acute care in seven countries, using the flash mob study design. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 474 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06459-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06459-4