Abstract

Background

The incidence of tuberculosis (TB) is high in Uganda; yet, TB case detection is low. The population-based survey on the prevalence of TB in Uganda revealed that only 16% of presumptive TB patients seeking care at health facilities were offered sputum microscopy or chest-X ray (CXR). This study aimed to determine the magnitude of, and patient factors associated with missed opportunities in TB investigation at public health facilities of Wakiso District in Uganda.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional survey was conducted at 10 high volume public health facilities offering comprehensive TB services in Wakiso, Uganda, among adults (≥18 years) with at least one symptom suggestive of TB predefined according to the World Health Organisation criteria. Using exit interviews, data on demographics, TB symptoms, and clinical data relevant to TB diagnosis were collected. A missed opportunity in TB investigation was defined as a patient with symptoms suggestive of TB who did not have sputum and/or CXR evaluation to rule out TB. Poisson regression analysis was performed to determine factors associated with missed opportunities in TB investigation.

Results

Two hundred forty-seven (247) patients with presumptive TB exiting at antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinics (n = 132) or general outpatient clinics (n = 115) at public health facilities were recruited into this study. Majority of participants were female (161/247, 65.2%) with a mean + SD age of 35.1 + 11.5 years. Overall, 138 (55.9%) patients with symptoms suggestive of TB disease did not have sputum and/or CXR examinations. Patients who did not inform health workers about their TB related symptoms were more likely to miss a TB investigation (adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR): 1.68, 95%CI; 1.36–2.08, P < 0.001). However, patients who reported duration of cough of 2 weeks or more were less likely to be missed for TB screening (aPR; 0.69, 95%CI; 0.56–0.86, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

There are substantial missed opportunities for TB diagnosis in Wakiso District. While it is important that patients should be empowered to report symptoms, health workers need to proactively implement the WHO TB symptom screen tool and complete the subsequent steps in the TB diagnostic cascade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global public health problem and a leading cause of death from an infectious agent [1]. In 2018, it was estimated that there were 10 million new TB cases worldwide and 1.5 million TB deaths [1]. About 24% of these TB cases were in sub-Saharan Africa which accounts for about 86% of the global TB/HIV burden [1].

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the End TB strategy aim to end TB by 2030 [2]. Early diagnosis of TB is a critical component of the End TB interventions [2]. Despite roll out of new diagnostic tools such as GeneXpert to improve diagnosis, TB cases are still missed globally. In 2018, about 3 million people with TB were either missed or not reported and only one in three people with drug resistant TB accessed care [1]. Missed TB cases result in delayed treatment and premature death, complications, community and nosocomial transmission, and catastrophic costs for families [3, 4].

Uganda National TB and Leprosy Control Program recommends prompt screening for TB among all persons seeking health care at healthcare facilities [5, 6]. However, the population based survey on the prevalence of TB in Uganda found that only 16% of patients with symptoms suggestive of TB who visited health facilities were investigated for TB by sputum microscopy or Chest X-ray (CXR) [7]. Similar observations were reported from South Africa and India [8,9,10].

Previous studies on factors associated with missed TB cases in health facilities revealed that: health system factors such as lack of training, low staff motivation, and high workload; and contextual factors including time and cost borne by patients to seek and complete TB evaluation, poor health literacy, and stigma against patients contribute to missed opportunities in TB investigation at public health facilities [11].

In South Africa, a study done at clinics participating in a cluster randomised trial found that patient factors associated with TB investigation include increasing number of symptoms such as longer duration of cough, unintentional weight loss, and night sweats and reporting symptoms to healthcare worker [8].

There is a dearth of knowledge on patient factors associated with missed TB investigation among adults with TB related symptoms in public health facilities in resource limited settings. The objective of this study was to determine the magnitude of, and patient factors associated with missed opportunities in TB investigation at public health facilities in a peri-urban district in Central Uganda.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between April and June 2018 among adults who presented with symptoms suggestive of TB predefined according to the WHO criteria. Patients exiting 10 high volume public health facilities in Wakiso district in Uganda constituted the study population. In 2014, Wakiso District had an estimated population of 2.0 million [12]. About 60% of this population live in the urban areas [12]. Since 2010, interventions have been implemented to improve the case detection rate in the district. The interventions included: the DETECT child TB project; and roll out of national TB/HIV guidelines [13]. However, TB case detection rate remain low at about 57% [13].

Wakiso district has seven health sub districts namely Entebbe, Busiro South, Busiro North, Busiro East, Kyadondo North, Kyadondo South, and Kyadondo East. It hosts 67 public health facilities that offer free comprehensive primary health care services including screening and testing for TB. TB screening and testing services are expected to be offered at all care entry points especially outpatient, HIV/ART clinic, and Maternal & Child Health departments.

Study population

The study population included adults exiting the public health facilities at two care entry points; HIV/ART clinic and outpatient department. We included all adults aged 18 years or older with at least one symptom suggestive of TB predefined according to WHO criteria (namely - cough lasting for 2 weeks or more, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, and fever). In addition, for people living with HIV, we included patients presenting with cough of any duration. Patients who had sputum sent for TB investigation prior to current visit and TB patients who were already on TB treatment were excluded from the study and so were patients who were deemed incompetent to provide an informed written consent. In addition, patients with symptoms of TB other than those predefined by WHO criteria were also excluded from this study.

Sample size

We calculated a sample size of 255 clients using Kish (1965) formula for cross sectional studies [14]. According to a study to evaluate TB diagnostic practices at five primary care health facilities in Uganda for 1 year, proportion of patients with symptoms suggestive of TB offered sputum examination was 21% [15]. Hence p = 0.21, q = 0.79, d (acceptable degree of error) =0.05, z (standard normal value corresponding to 95% confidence interval) =1.96.

Therefore \( N=\frac{(1.96)^2x\ (0.21)x\ (0.79)}{(0.05)^2} \) = 255 participants.

Sampling procedure

Four health sub-districts were randomly selected from the seven health sub districts in Wakiso district. We then purposively selected 10 high volume health centres from the four health sub districts. They included Entebbe Hospital, Kasangati Health Centre IV, Wakiso Health Centre IV, Kajjansi Health centre IV, Buwambo Health Centre IV, Bweyogerere Health Centre III, Kiira Health Centre III, Nabweru Health centre III, Nsangi Health centre III, and Nakawuka Health Centre III. Each high-volume facility received an average of 98 (range 61–160) patients per day. The number of patients to be interviewed at each facility was determined by proportionate to size sampling. This depended on the average number of daily outpatient attendance over the last 3 months.

Data collection

Patients were screened consecutively for interviews as they exited the different clinicians’ rooms at OPD and HIV clinics. An interviewer-administered structured questionnaire was used to collect data on demographics, TB symptoms, and other clinical data relevant to TB diagnosis. Participants were also asked if they had sputum and/ or a CXR requested by a healthcare worker at that visit. If sputum and/ or CXR had not been requested, they were referred back to the clinic staff for appropriate investigations.

Quality control

The questionnaire used was pretested in two public health facilities and these were not part of the study sample. Research assistants were trained and supervised during data collection. Filled questionnaires were reviewed daily to check for completeness and consistency.

Data analysis

Data were entered in Epidata version 3.1 database (EpiData database, Odense, Denmark). Data were cleaned and exported to Stata v14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

Continuous variables were described using means, or medians and the corresponding standard deviations or the interquartile ranges respectively while categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. The proportion of missed opportunities in TB investigation was calculated by dividing the number of patients with symptoms suggestive of TB who did not have sputum examination and/or CXR requested to rule out TB disease by the total number of patients with symptoms suggestive of TB disease.

At bivariate analysis, modified Poisson regression was used to identify factors significantly associated with missed TB diagnosis. A p < 0.05 was used as level of significance at the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) to test this association. Prevalence ratio was used as the measure of association. At multivariate analysis, factors associated with the primary outcome at bivariate analysis were included in a multivariable model and adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% CI were estimated. A p < 0.2 was used as a cut off to determine which variables to carry for multiple modified Poisson regression model to build the final model. Forward regression technique was used to build the multiple modified Poisson regression model while assessing the model variables for significance at p < 0.05 and 95% CI. An adjusted R2 was generated for the final model to determine to what extent the factors were associated with the outcome of interest.

Ethical considerations

Makerere University School of Public Health Research and Ethics Committee (FWA00011353) provided ethical approval and Wakiso District Health Office provided approval and permission to perform the study in the public health facilities.

Results

Characteristics of the respondents

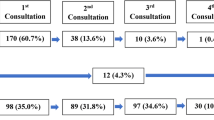

From April 2018 to June 2018, we screened 1543 adults upon exiting public health facilities for eligibility of whom 261 met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of this, 14 (5%) declined enrollment and 247 (95%) were enrolled.

The mean ± SD age of the participants was 35.1 ± 11.5 years, 161(65.2%) were female, 120 (48.6%) had attained primary education and 93 (37.6%) were in full-time employment. Just over half (n = 132,53.4%) of the participants were enrolled from the ART clinic, and 128 (51. 8%) resided in urban areas.

Majority (191/247, 77.3%) of the patients had cough and most (116/191, 60.7%) of them had had cough for between 2 and 4 weeks. Only 23/247(9.3%) had the four classical constitutional symptoms of TB. Majority (226/247, 91.5%) of the patients knew their HIV status; with nearly two-third (144/226, 63.7%) being HIV positive and 139/144 (96.5%) were on ART.

Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Missed opportunities for TB investigation

Of the 247 enrolled study participants, 138 (55.9%) had at least one symptom suggestive of TB disease but were not offered sputum and/or CXR investigations. Overall, 160/247 (64.8%) reported TB related symptoms to health workers. Less than half (103/247, 41.7%) of the participants were asked by the treating clinician to provide a sputum sample for microscopy and only 19/247 (7.7%) were offered a request for CXR examination. Another 13/247 (5%) were asked to provide both sputum for microscopy and CXR.

Factors associated with missed opportunities for TB investigation

Only duration of cough (APR; 0.69, 95%CI; 0.56–0.86, p < 0.001) and not informing the health worker about TB symptoms (APR; 1.68, 95%CI; 1.36–2.08, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with missed opportunities of TB investigation (Table 2).

Discussion

TB is a preventable and curable infectious disease that continues to infect and claim the lives of a significant number of individuals globally [1]. Early identification of symptoms and appropriate investigations are important for early diagnosis and institution of anti-TB regimen. TB case detection rates has remained low especially in the developing world, including Uganda [1]. The present study was conducted to determine patient factors associated with missed opportunities in TB investigation at public health facilities.

Our study reports a high prevalence of missed opportunities for TB investigations. However, this was relatively lower than what was reported during the Uganda national prevalence survey which stood at 84% [7]. The proportion of patients with symptoms suggestive of TB who were not asked by health workers to provide sputum samples for examination in this study was relatively lower at about 56% compared to previously published studies conducted in Uganda, Ghana, and South Africa reporting a relatively higher proportions ranging from 75 to 90% [15,16,17] . The observed differences could be attributed to the improved knowledge and vigilance by the health workers through different interventions such as facility-based trainings and mentorships by the government and its partners. However, putting this together, the proportion of missed opportunities for TB investigation is still high suggesting existing gaps in the TB case finding initiatives. Interventions to enhance TB case finding at the health facility need to be implemented.

Of further interest, our study found that reporting symptoms to health worker was associated with having sputum samples sent for TB investigation and/or CXR examination done. Similar findings were reported in South Africa where reporting symptoms to health workers was one of the strongest factors associated with having sputum samples sent for TB investigations [8]. This suggests that patients who had a positive symptom screen for TB were more likely to undergo TB evaluation. Therefore, there is need for health workers to actively screen for TB at health facilities using the standardized TB symptom screen tool.

Furthermore, our study found that patients with cough of duration of 2 weeks or more were about 30% less likely to miss TB investigation compared to those with cough of less than 2 weeks duration. This finding was not in agreement with a study in South Africa where duration of cough did not result into a statistically significant association with TB investigation [9]. This may suggest that patients who meet criteria for presumptive TB but have cough less than 2 weeks are likely to be miss TB evaluation. Moreover, a significant proportion of our study participants were HIV positive who should be screened for TB regardless of the duration of cough. Health workers should be sensitized to adhere to the TB screening and diagnosis protocols that recommend TB evaluation for all patients who meet the WHO predefined criteria.

Our study has some limitations. We used a cross sectional study design that mainly depended on self-reported responses that could be affected by recall bias. Additionally, this study design does not allow for inference for causality. Also, we focused majorly on two entry points at the public health facility –outpatient department and HIV care clinic, which may affect generalizability of our findings at the public health facility. Using the WHO predefined criteria also limited our study from investigating missed opportunities in the diagnosis of extra-pulmonary TB. Furthermore, we didn’t ask whether some patients had been evaluated using urine LAM as one of the TB investigations since it wasn’t widely available at the time. Consequently, this could have limited us from identifying some patients who could have been evaluated using urine LAM technique. Lastly, more females than males were included despite the fact that in Uganda more males have TB than females. This may mean that more males missed opportunities for TB investigation by simply not presenting to health care facilities. However, we report important gaps in facility-based investigations for TB disease in routine clinical practice that merits further research into clinician and patient factors that limits timely TB diagnosis.

Conclusion

The study showed a high proportion of the patients with symptoms suggestive of TB disease did not have sputum and/or CXR requested for TB investigation, which translates into a high prevalence of missed opportunities for TB investigations in these clinics. Patients who did not inform health workers about their symptoms and those that had shorter duration of cough were more likely to miss TB investigations, which highlights gaps in implementing TB screening and diagnosis protocols by clinicians in public health facilities. While it is important that patients should be empowered to report symptoms, health workers need to proactively implement the WHO TB symptom screen tool with fidelity in order to explore all TB symptoms among patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.I26.1.78.

World Health Organisation. Implementing the End TB Strategy: The Essentials, 2015. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2015/end_tb_essential.pdf?ua=1

Uys PW, Warren RM, van Helden PD. A threshold value for the time delay to TB diagnosis. PLoS One. 2007;2(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000757.

Toman K. Tuberculosis case-finding and chemotherapy. Citeseer; 1979.

Ministry of Health Uganda. Uganda national guidelines for tuberculosis infection control in health care facilities, congregate settings and households. published online 2010. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/uganda_hiv_tb.pdf

Ministry of Health Uganda. Manual of the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme. 2nd ed; 2010. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/uganda_tb.pdf

Ministry of Health Uganda. The Uganda National Tuberculosis Prevalence Survey, 2014–2015, 2016. https://www.health.go.ug/cause/the-uganda-national-tuberculosis-prevalence-survey-2014-2015-survey-report/

Chihota VN, Ginindza S, McCarthy K, Grant AD, Churchyard G, Fielding K. Missed opportunities for TB investigation in primary care clinics in South Africa: experience from the XTEND trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138149.

Kweza PF, Van Schalkwyk C, Abraham N, Uys M, Claassens MM, Medina-Marino A. Estimating the magnitude of pulmonary tuberculosis patients missed by primary health care clinics in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(3):264–72. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.17.0491.

Subbaraman R, Nathavitharana RR, Satyanarayana S, Pai M, Thomas BE, Chadha VK, et al. The tuberculosis cascade of care in India’s public sector: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):1–38. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002149.

Cattamanchi A, Miller CR, Tapley A, Haguma P, Ochom E, Ackerman S, et al. Health worker perspectives on barriers to delivery of routine tuberculosis diagnostic evaluation services in Uganda: a qualitative study to guide clinic-based interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0668-0.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). National population and housing census 2014, 2017. https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/2014CensusProfiles/WAKISO.pdf

Ministry of Health Uganda. Annual Tuberculosis Report June 2017–June 2018, 2018.

Kish L. Survey sampling: Wiley; 1965.

Davis JL, Katamba A, Vasquez J, Crawford E, Sserwanga A, Kakeeto S, et al. Evaluating tuberculosis case detection via real-time monitoring of tuberculosis diagnostic services. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(3):362–7. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201012-1984OC.

Buregyeya E, Criel B, Nuwaha F, Colebunders R. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Wakiso and Mukono districts, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-586.

Amenuvegbe GK, Francis A, Fred B. Low tuberculosis case detection: a community and health facility based study of contributory factors in the Nkwanta south district of Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2136-x.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants, research participants, facility managers and district officials in Wakiso district.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (KTK, NN, AK, FB, JBB, SOB) significantly contributed to the conceptualization, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained from the Makerere University School of Public Health Research and Ethics Committee (FWA00011353). Participants provided written informed consent before divulging any information and collection of data. Principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the conduct of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kakame, K.T., Namuhani, N., Kazibwe, A. et al. Missed opportunities in tuberculosis investigation and associated factors at public health facilities in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 359 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06368-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06368-6