Abstract

Background

Early readmission amongst older safety-net hospitalized adults is costly. Interventions to prevent early readmission have had mixed success. The role of perceived social support is unclear. We examined the association of perceived social support in 30-day readmission or death in older adults admitted to a safety-net hospital.

Methods

This is an observational cohort study derived from the Support From Hospital to Home for Elders (SHHE) trial. Participants were community-dwelling English, Spanish and Chinese speaking older adults admitted to medicine wards at an urban safety-net hospital in San Francisco. We assessed perceived social support using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). We defined high social support as the highest quartile of MSPSS. We ascertained 30-day readmission and mortality based on a combination of participant self-report, hospital and death records. We used multiple/multivariable logistic regression to adjust for patient demographics, health status, and health behaviors. We tested for whether race/ethnicity modified the effect high social support had on 30-day readmission or death by including a race-social support interaction term.

Results

Participants (n = 674) had mean age of 66.2 (SD 9.0), with 18.8% White, 24.8% Black, 31.9% Asian, and 19.3% Latino. The 30-day readmission or death rate was 15.0%. Those with high social support had half the odds of readmission or death than those with low social support (OR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.26–0.88). Interaction analyses revealed race modified this association; higher social support was protective against readmission or death among minorities (AOR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.16–0.76) but increased likelihood of readmission or death among Whites (AOR = 3.7, 95% CI 1.07–12.9).

Conclusion

In older safety-net patients nearing discharge, high perceived social support may protect against 30-day readmission or death among minorities. Assessing patients’ social support may aid targeting of transitional care resources and intervention design. How perceived social support functions across racial/ethnic groups in health outcomes warrants further study.

Trial registration

NIH trials registry number ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01221532.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Early hospital readmissions are costly to the health care system and considered markers of poor quality; up to 20% of hospitalized patients experience readmission within 30 days [1]. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program has focused attention on preventing 30-day hospital readmissions [2], spurring development of transitional care interventions. These studies show mixed results [3,4,5,6,7], particularly in safety-net settings with higher proportions of racial/ethnic minorities, non-English speakers, and patients with lower socioeconomic status [8].

One reason for difficulties reducing readmission rates is appropriate targeting of interventions. Known clinical risk factors associated with early readmission include history of recent prior hospitalization, high burden of comorbid illness and specific diagnoses [9]. But using only these factors, predicting readmission risk remains challenging [10]. According to Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, predisposing factors (eg. demographics, health beliefs), enabling resources (eg. access to care, social support), in addition to need (eg. clinical status) influence utilization [11].

Social support, a social network’s provision of psychological and material resources to benefit an individual’s ability to cope with stress, may serve as an enabling resource for health services use [11, 12]. Social support may buffer against the medical, financial, and emotional stresses of hospitalization [13, 14]. While structural factors (ie. living alone, marital status) are proxies for social support, assessing one’s perceived (ie. functional) social support may better reflect health utilization risk [15,16,17,18]. But its role in readmission amongst hospitalized safety-net patients is unclear. We address this gap by examining the role of a multi-dimensional measure of perceived social support in predicting 30-day readmission rates or death in a cohort of older, multi-ethnic hospitalized adults at a safety-net hospital. We hypothesized that individuals with high social support are protected against early readmission or death.

Methods

Study design and sample

The study was part of a randomized controlled trial, the Support From Hospital to Home for Elders (SHHE) [7], assessing a nurse-led hospital discharge intervention in an urban, publicly-funded, acute care hospital. Details about the trial are provided elsewhere [7]. Briefly, the intervention consisted of in-person education by a trained study nurse prior to discharge, a patient-centered booklet for post-discharge care, and discharge follow-up telephone calls.

Between July 2010 and August 2012, we enrolled participants admitted to the medicine, cardiology, or neurology services of San Francisco General Hospital, an urban safety-net hospital [19]. Participants were eligible for the study if they spoke English, Spanish, or Chinese. The study was initially restricted to participants aged 60 and older, but the eligibility criteria expanded in March 2011 after 239 participants enrolled to include those aged 55 and older. We excluded participants who were [1]: transferred from an outside hospital [2]; admitted as a planned hospitalization [3]; likely to be discharged to an institutional setting [4]; unable to consent due to lack of understanding, cognitive impairment, or other reason [5]; diagnosed with metastatic cancer; and [6] unable to participate in telephone follow-up. The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco approved the above procedures.

Measures

Data sources

We conducted language-concordant baseline interviews at bedside during hospitalization and a follow-up telephone interview 30 days after discharge. We reviewed administrative and health record data for information on comorbidities and readmissions.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was 30-day readmission or death. We obtained administrative records at the index hospital and two affiliated university hospitals to ascertain readmissions data; for an additional six hospitals, we obtained administrative records for any patient who reported any hospitalization at the follow up interview. For other hospitals, we requested confirmation dates of readmission that patients reported. We identified deaths using hospital, health department, and state vital statistics records for patients who did not complete the 30-day follow up interview [7].

Primary predictor: perceived social support

We assessed social support using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [20]. The MSPSS is a validated scale that asks participants 12 questions about their perceived social support (i.e., emotional support, comfort, and assistance in making decisions) from family, friends, or significant others (Table 1). Participants rated each question on a 7 point Likert like scale from “very strongly disagree” (score of 0) to “very strongly agree” (score of 7) to derive the final score up to 84. We defined social support in categories based on quartiles (5–52, 53–64, 65–74, 75+). Because the rates of 30-day readmission and death were similar amongst the lower three quartiles, we collapsed the measure into a binary predictor with scores > 74 indicating high social support, compared to those with very low, low, and medium social support.

Other measures

At the baseline interview, participants reported date of birth, sex, race/ethnicity (Black/African-American Non-Latino; White, Non-Latino; Latino/Hispanic, Asian, or Other), total household income (≤$20,000 per year vs > $20,000 per year) [21], last completed grade in school (≤ 12 years vs > 12 years) and limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) two weeks prior to admission (1+ ADL limitation vs none). We asked what language the participant spoke at home, and how well the participant spoke English (not at all, not well, well, and very well). We defined low English proficiency as those participants speaking English “not at all” or “not well” [22]. We measured substance use using the WHO ASSIST instrument [23] and participants self-reported any tobacco use and illicit drug use in the prior 3 months. We assessed depression at admission using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (we defined depression as a PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) [24], and health literacy using a self-reported 3-item scale (we defined a score ≥ 9 as inadequate health literacy) [25]. We asked participants if they lived alone, with a spouse/partner, or in another situation. We asked participants if they were hospitalized in the six months prior to enrollment. We administered the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) to evaluate cognitive impairment, defined as a TICS score less than 20 [26]. We calculated the Charlson co-morbidity index using administrative ICD-9 codes from the index hospitalization (scores 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+, higher scores indicating higher co-morbidity) [27].

Analysis

We used chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables to compare participants in the highest quartile of social support versus those in the lower three quartiles. We described the rates of high social support across White, Black, Asian, and Latino populations in the cohort.

We used multiple/multivariable logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (and 95% CI) of 30-day readmission or death associated with the highest quartile of social support. We adjusted for variables chosen a priori based on literature or with significant association (p < .20) with readmission or death in bivariate analyses: demographics (age, race, sex), limited English proficiency, low health literacy, depression, cognitive impairment, any baseline ADL difficulties 2 weeks prior to admission, current smoker, hospitalized in prior 6 months, and Charlson comorbidity category. We conducted Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test to determine model fit. In a secondary analysis, we restricted the outcome to 30-day readmission and excluded patients who died to examine the effect of high social support on readmission alone.

We repeated this model using each source of social support (spouse, family, friends) as the predictor. We ran our models with and without our living situation variable to assess whether perceived social support was associated with readmission or death independent of structural support. We included treatment group assignment as a variable in the model but removed it from the final model because it was not significant. We tested for whether race/ethnicity modified the effect high social support had on 30-day readmission or death by including a race-social support interaction term. We created a new variable for White and non-White race because no Latino participants with high social support experienced 30-day readmission or death. Because the interaction was significant, we presented stratified results by race (White vs non-White).

We conducted all the analyses using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of participants

There were 674 participants in the cohort with mean age of 66.2 years; 43.8% were women. The cohort was diverse: 24.8% were Black, 19.3% were Latino, and 31.9% were Asian. The majority of participants had annual incomes less than $20,000 (88.6%). Many reported limited English proficiency (37.2%) and had inadequate health literacy (62.7%) (Table 2). The distribution of social support using the MSPSS was skewed, with a median score of 64 (out of 84) and an interquartile range of 52–74. Compared to participants in the low social support group, those in the high social support group were more likely to be Latino (35.5% vs 14.6%) and less likely to be White (9.9% vs 21.5%). Participants with high social support were also more likely to be female, be non-smokers, and report less illicit drug use within the prior 3 months, and were less likely to have depression or live alone.

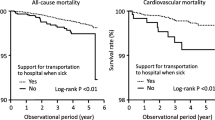

Relationship between social support and 30-day readmission or death

Among the participants, 14.3% were readmitted within 30 days and 0.7% died-- a combined readmission or death rate of 15.0%. Amongst those in the highest quartile of social support, 8.6% experienced readmission or death, compared to 16.9, 14.1, and 18.1% of participants with very low, low, and medium social support. In unadjusted analyses, high social support was associated with decreased odds of 30-day readmission or death (OR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.26–0.88). After adjustment, the association was attenuated but suggestive of a protective effect of social support (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.33, 1.21) (Table 3). Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test (p = 0.64) showed adequate fit. Our secondary analysis examining 30-day readmission rate alone as the outcome, excluding patients who died, revealed similar results (AOR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.34, 1.24). The change in odds ratio, and loss of statistical significance, was primarily due to adjustment for race/ethnicity, which subsequent interaction analysis showed to modify the association of social support with our outcome. Adding living situation to our models did not alter our findings.

There were differences in the sources of social support and association with 30-day readmission or death (Table 4). Participants most reported receiving high social support from a spouse (41.1%), followed by family (24.8%) and friends (21.4%). After adjustment, those who reported receiving high social support from friends had one-third the odds of experiencing 30-day readmission or death compared to those with lower levels of social support from friends (AOR, 0.32; 95% CI 0.14, 0.74). Participants with high social support from a spouse had lower 30-day readmission or death rates, but the association was not significant (AOR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.45, 1.25). Social support from family members was not associated with 30-day readmission or death (AOR, 1.10; 95% CI 0.62, 1.99).

Interaction analysis

We found evidence that non-White vs White race/ethnicity modified the effect of high social support on odds of 30-day readmission or death (Table 5, p-value for interaction p = .002). Amongst non-Whites, those with high social support had lower odds of 30-day readmission or death compared to those with low levels of social support (AOR, 0.35; 95% CI 0.16–0.76). In contrast, Whites with high social support had higher odds of 30-day readmission or death compared to Whites with low levels of social support (AOR, 3.72; 95% CI 1.07–12.89).

Discussion

Among ethnically diverse, older adults hospitalized at a safety-net hospital, we found that those with high perceived social support had lower rates of 30-day readmission and death. After adjustment for health factors associated with readmission, the association was not significant but still suggested a protective effect of social support. We also found that while spouses are the most common sources of social support, those who perceived high social support from friends were least likely to experience early readmission and death. Finally, we found that race modified the effect of social support on 30-day readmission and death.

To date, the role of perceived social support on early readmission has been unclear. Prior studies of hospitalized heart failure patients show a positive effect of high levels of perceived social support and reduced readmission [28] but several studies of hospitalized COPD patients found no association between perceived social support and hospital readmissions at two weeks, 3 months, or 12 months [29]. A study of general hospitalized patients found no association between social support and 30-day readmission, though in that study social support was assessed with a one-item question of having someone to help at home [30]. Our findings support a role for perceived social support in preventing early readmission.

Social support may operate as an enabling resource in Andersen’s model of care utilization. In this model, utilization is not only based on need for care, but also enabling resources. Perceived social support may prevent early readmission through the ability of patients to access resources necessary for recovery from hospitalization. Our results also suggest that social support may operate via a threshold effect, because participants in the lower three quartiles of social support had similar rates of early readmission or death. Prior studies found threshold effects of social support in adjustment outcomes for breast cancer survivors [31] and perceived stress in a cohort of firefighters [32], though in contrast to our results, they found social support effects diminished at higher levels. It may be that preventing readmission requires harnessing additional sources of social support, from multiple sources. This finding is preliminary and requires additional exploration.

This study supports assessing perceived social support in addition to structural measures such as living alone. Structural social support and perceived social support are related but different concepts -- living alone is often used as a proxy for low social support but can also be a marker for good health and thereby associated with lower hospitalization risk [33]. Adjusting for living alone in our study did not substantively affect our findings. It may be that quality of support matters most in healthcare utilization, and this is best measured by evaluating how supported the patient feels. Social support is a complex concept that may not be well captured by proxy measures.

Our finding of the importance of social support from friends contradicts an early study that found social support provided by family members had stronger association with health outcomes, though that study did not assess impact on early readmission [34]. Cantor’s model of hierarchical compensation posits that older adults select from a hierarchy of supportive relationships, with spouses and family members typically selected first [35]. During times of stressful events such as hospitalization, the ability to access additional social support from an extended social network may be important post-discharge. Spousal or familial support may not be sufficient to prevent re-hospitalization when unexpected needs arise. The importance of support provided by friends may support interventions that extend support beyond the patient’s immediate family (eg community health workers).

We found that race modifies the effect of perceived social support on readmission, with high social support being protective against readmission among minorities and Latinos in particular. This may reflect how social support varies across race and culture. Multiple studies show high social support predicts improved health outcomes among Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics, and social support may contribute to the Latino health paradox phenomenon [36,37,38]. A study of 7374 older low-income patients discharged to home found that Black elders were more likely to report having care support, and that White elders experienced greater stress at discharge than their Black, Asian, and Latino counter parts [39]. An observational study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found similar interaction between non-White race and high social support and decreased odds of hypertension diagnosis [40]. On the other hand, in Whites, the role of social support and readmission is less clear. While we found an association between high social support and increased utilization, there were few patients with high social support, and subsequent wide confidence interval. In these patients, high social support may indicate higher medical acuity or social vulnerability that are not captured in the data, or that these patients’ social support appropriately directed them to seek out medical care post-discharge. Alternatively, lower levels of institutional trust in health care by non-Whites compared to Whites might also explain the differential effects of social support by race [41] -- social support may help patients disinclined to return to the hospital avoid readmission without adverse health consequences. Our findings suggest that social support matters in minorities, particularly Latinos. That few White patients reported high levels of social support compared to minorities also bears noting—White patients in safety-net populations are different medically than those in non-safety-net settings [42], and our findings may suggest they differ socially as well. The influence of perceived social support across racial/ethnic groups deserves further study.

Our findings have implications for practice. A potential reason for the mixed impact of care transitions interventions on readmission is that programs are not targeting the right patients. Medically complex safety-net patients who have high levels of social support may not need the resources these programs provide to avoid unnecessary care utilization. Prior transitional care evaluations showing efficacy such as Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions) [43] and Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT) [44] included interventions that bolster social support of recently discharged patients in minority serving institutions; future transitions of care interventions should focus on ways of identifying patients with low social support, and then harnessing a patient’s social support network to avoid early readmission. The MSPSS can be practically administered by discharge planners to tailor transitional care planning.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. Our cohort was derived from those agreeing to enroll in a randomized controlled trial and may differ from the source population. The 30-day readmission rate of 14.3% was lower than anticipated and might reflect patient selection as well as the quality of care delivered during the trial period. In addition, safety-net populations differ in important ways from the general population, limiting generalizability. There may be differences in how Whites and non-Whites interpreted the social support measure. Finally, this was an observational study susceptible to confounding by unmeasured or incompletely measured variables.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to explore the role that perceived social support and the sources of that support have on early readmission in a cohort of low income hospitalized elders. Our results suggest that patients, particularly those of racial/ethnic minorities with high levels of perceived social support have lower odds of experiencing 30-day readmission or death. Future studies on how perceived social support functions in readmission might aid in in discharge intervention design.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- BOOST:

-

Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions

- CMS:

-

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Disease

- IMPaCT:

-

Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets Involvement Screening Test

- LEP:

-

Limited English Proficiency

- MSPSS:

-

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- SHHE:

-

Support From Hospital to Home for Elders

- TICS:

-

Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status

- WHO ASSIST:

-

World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance

References

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–28.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital readmissions reduction program. 2014 [cited 2015 March 28]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html.

Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1460–7.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–8.

Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–20.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–87.

Goldman LE, Sarkar U, Kessell E, Guzman D, Schneidermann M, Pierluissi E, et al. Support from hospital to home for elders: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(7):472–81.

Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2061–9.

Librero J, Peiro S, Ordinana R. Chronic comorbidity and outcomes of hospital care: length of stay, mortality, and readmission at 30 and 365 days. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(3):171–9.

Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–98.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57.

Pilisuk M, Boylan R, Acredolo C. Social support, life stress, and subsequent medical care utilization. Health Psychology. 1987;6(4):273–88.

Garey L, Reitzel LR, Anthenien AM, Businelle MS, Neighbors C, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Support buffers financial Strain’s effect on health-related quality of life. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(4):497–510.

Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, deGruy FV, Kaplan BH. Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Med Care. 1989;27(3):221–33.

DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004;23(2):207–18.

Blazer DG. Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(5):684–94.

Wethington E, Kessler RC. Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27(1):78–89.

San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center San Francisco. Available from: https://zuckerbergsanfranciscogeneral.org/. Accessed, 5 Mar 2019.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41.

Operario D, Adler NE, Williams DR. Subjective social status: reliability and predictive utility for Global Health. Psychol Health. 2004;19:237–46.

USC B. English Proficiency question U.S. summary: 2000 census US profile. Washington DC. 2000.

WHO ASSIST Working Group. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–94.

Reuland DS, Cherrington A, Watkins GS, Bradford DW, Blanco RA, Gaynes BN. Diagnostic accuracy of Spanish language depression-screening instruments. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(5):455–62.

Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Lopez A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):265–71.

Barber M, Stott DJ. Validity of the telephone interview for cognitive status (TICS) in post-stroke subjects. Int J Geriat Psychiat. 2004;19(1):75–9.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: an overview of the literature. J Cardiovascular Nurs. 2005;20(3):162–9.

Barton C, Effing TW, Cafarella P. Social support and social networks in COPD: a scoping review. Copd. 2015;12(6):690–702.

Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, Bell CM, Kaboli PJ, Auerbach AD, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211–9.

Mallinckrodt B, Armer JM, Heppner PP. A threshold model of social support, adjustment, and distress after breast cancer treatment. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(1):150–60.

Varvel SJ, He Y, Shannon JK, Tager D, Bledman RA, Chaichanasakul A, et al. Multidimensional, threshold effects of social support in firefighters: is more support invariably better? [references]. (4):458–465.

Ennis SK, Larson EB, Grothaus L, Helfrich CD, Balch S, Phelan EA. Association of living alone and hospitalization among community-dwelling elders with and without dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1451–9.

Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):488–531.

Cantor MH. Neighbors and friends: an overlooked resource in the INformal support system. Res Aging. 1979;1(4):434–63.

Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: testing the concept of familism. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1852–8.

Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, McCurley JL, Isasi CR, Penedo FJ, Daviglus ML, et al. Associations of structural and functional social support with diabetes prevalence in U.S. Hispanics/Latinos: results from the HCHS/SOL sociocultural ancillary study. J Behav Med. 2015;38(1):160–70.

Ruiz JM, Hamann HA, Mehl MR, O’Connor M-F. The Hispanic health paradox: from epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Proc Intergroup Relations. 2016;19(4):462–76.

Peng TR, Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH. Social support, home health service use, and outcomes among four racial-ethnic groups. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):503–13.

Bell CN, Thorpe RJ Jr, Laveist TA. Race/ethnicity and hypertension: the role of social support. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(5):534–40.

Guerrero N, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA, Jacobs EA. Determinants of trust in health care in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):553–7.

Balasubramanian BA, Garcia MP, Corley DA, Doubeni CA, Haas JS, Kamineni A, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in obesity and comorbidities between safety-net- and non safety-net integrated health systems. Medicine. 2017;96(11):e6326.

Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, Howell E, Halasyamani L, Maynard G, et al. Project BOOST: Effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. Journal of hospital medicine : an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013.

Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, White ML, McCollum S, Sellman J, et al. Patient-centered community health worker intervention to improve posthospital outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):535–43.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (DG, US, LG, JC, MC) and by the UCSF primary care research fellowship Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32HP19025) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded PCOR K12 award (K12HS022981) (BC). The funding source had no access to the data, role in design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BC and MK conceived and designed the study; LG, US, JC, MK were involved in acquisition of data; BC, MK, DG, LG, UC, JC, SS were involved in analysis and interpretation of data; BC drafted the manuscript; MK, SS, LG, UC, DG, JC were involved in critical revision; BC, MK, LG, US, DG, SS, JC read and approved final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, B., Goldman, L.E., Sarkar, U. et al. High perceived social support and hospital readmissions in an older multi-ethnic, limited English proficiency, safety-net population. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 334 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4162-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4162-6