Abstract

Background

The medical discharge letter is an important communication tool between hospitals and other healthcare providers. Despite its high status, it often does not meet the desired requirements in everyday clinical practice. Occurring risks create barriers for patients and doctors. This present review summarizes risks of the medical discharge letter.

Methods

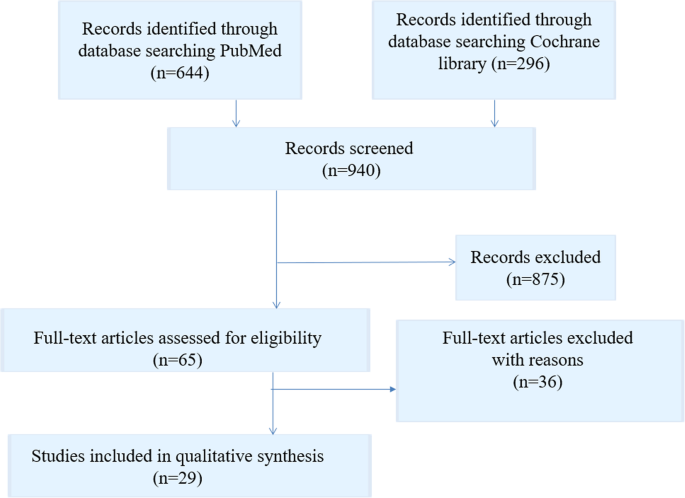

The research question was answered with a systematic literature research and results were summarized narratively. A literature search in the databases PubMed and Cochrane Library for Studies between January 2008 and May 2018 was performed. Two authors reviewed the full texts of potentially relevant studies to determine eligibility for inclusion. Literature on possible risks associated with the medical discharge letter was discussed.

Results

In total, 29 studies were included in this review. The major identified risk factors are the delayed sending of the discharge letter to doctors for further treatments, unintelligible (not patient-centered) medical discharge letters, low quality of the discharge letter, and lack of information as well as absence of training in writing medical discharge letters during medical education.

Conclusions

Multiple risks factors are associated with the medical discharge letter. There is a need for further research to improve the quality of the medical discharge letter to minimize risks and increase patients’ safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The medical discharge letter is an important communication medium between hospitals and general practitioners (GPs) and an important legal document for any queries from insurance carriers, health insurance companies, and lawyers [1]. Furthermore, the medical discharge letter is an important document for the patient itself.

A timely transmission of the letter, a clear documentation of findings, an adequate assessment of the disease as well as understandable recommendations for follow-up care are essential aspects of the medical discharge letter [2]. Despite this importance, medical discharge letters are often insufficient in content and form [3]. It is also remarkable that writing of medical discharge letters is often not a particular subject in the medical education [4]. Nevertheless, the medical discharge letter is an important medical document as it contains a summary of the patient’s hospital admission, diagnosis and therapy, information on the patient’s medical history, medication, as well as recommendations for continuity of treatment. A rapid transmission of essential findings and recommendations for further treatment is of great interest to the patient (as well as relatives and other persons that are involved in the patients’ caring) and their current and future physicians. In most acute care hospitals, patients receive a preliminary medical discharge letter (short discharge letter) with diagnoses and treatment recommendations on the day of discharge [5]. Unfortunately, though, the full hospital medical discharge letter, which is often received with great delay, is an area of constant conflict between GPs and hospital doctors [1]. Thus the medical discharge letter does not only represent a feature of process and outcome quality of a clinic, but also influences confidence building and binding of resident physicians to the hospital [6].

Beside the transmission of patients’ findings from physician to physician, the delivery of essential information to the patient is an underestimated purpose of the medical discharge letter [7]. The medical discharge letter is often characterized by a complex medical language that is often not understood by the patients. In recent years, patient-centered/patient-directed medical discharge letters are more in discussion [8]. Thus, the medical discharge letter points out risks for patients and physicians while simultaneously creating barriers between them.

Aim

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to identify patient safety risks associated with the medical discharge letter.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PubMed and Cochrane Database. Additionally, we scanned the reference lists of selected articles (snowballing). The following search terms were used: “discharge summary AND risks”, “discharge summary AND risks AND patient safety” and “discharge letter AND risks” and “discharge letter AND risks AND patient safety”. We reviewed relevant titles and abstracts on English and German literature published between January 2008 and May 2018 and started the search at the beginning of February 2018 and finished it at the end of May 2018.

Eligibility criteria

In this systematic review, articles were included if the title and/or abstract indicated the report of results of original research studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method approaches. Studies in paediatric settings or studies that do not handle possible risks of the medical discharge letter were excluded, as well as reports, commentaries and letters. Electronic citations, including available abstracts of all articles retrieved from the search, were screened by two authors to select reports for full-text review. Duplicates were removed from the initial search. Nevertheless, during the search of articles the selection, publication as well as language bias must be considered. Thereafter, full-texts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed to determine eligibility for inclusion. In the following Table 1 inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies are listed. Afterwards, key outcomes and main results were summarized. Differences were resolved by consensus. Finally, a narrative synthesis of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was conducted. Reference management software MENDELEY (Version 1.19.3) was used to organise and store the literature.

Data extraction

The data extraction in form of a table was used to summarize study results. The two authors extracted the data relating to author, country, year, study design, and outcome measure as well as potential risk factors to patient safety directly into a pre-formatted data collection form. After data extraction, the literature was discussed and synthesized into themes. The evaluation of the single studies was done using checklists [STROBE (combined) and the Cochrane Data collection form for intervention reviews (RCTs and non-RCTs)]. Meta-analysis was not considered appropriate for this body of literature because of the wide variability of studies in relation to research design, study population, types of interventions and outcomes.

Synthesis

Then a narrative synthesis was performed to synthesize the findings of the different studies. Because of the range of very different studies that were included in this systematic review, we have decided that a narrative synthesis constitutes the best instrument to synthesise the findings of the studies. First, a preliminary synthesis was undertaken in form of a thematic analysis involving searching of studies, listing and presenting results in tabular form. Then the results were discussed again and structured into themes. Afterwards, summarizing of included studies in a narrative synthesis within a framework was performed by one author.

This framework consisted of the following factors: the individuals and the environment involved in the studies (doctors, hospitals), the tools and technology (such as discharge letter delivery systems), the content of the medical discharge letter (such as missing content, quality of content), the accuracy and timeliness of transfer. These themes were discussed in relation to potential risks for patient’s safety. All articles that were included in this review were published before. The framework of this study was chosen following a previously published systematic review dealing with patient risks associated with telecare [9].

Results

The initial literature search in the two online databases identified 940 records. From these records, 65 full text articles were screened for eligibility. Then 36 full-text articles were excluded because they pertained to patient transfer within the hospital or to another hospital, or to patient hand-over situations. Finally, 29 studies were included in this review. Included studies are listed in Table 2. All document types were searched with a focus on primary research studies. The results of the search strategy are shown in Fig. 1.

From these 29 studies, 13 studies dealt with the quality analysis of discharge letters, 12 studies with delayed transmission of medical discharge letters and just as many with the lack of information in medical discharge letters. Only few studies dealt with training on writing medical discharge letters and with understanding of patients of their medical discharge letters. The descriptive information of the included articles is presented in Table 2. Overall quality of the articles was found to be acceptable, with clearly stated research questions and appropriate used methods.

Risk factors

In the following the identified major risk factors concerning the medical discharge letter are presented in a narrative summary.

Delayed delivery

The medical discharge letters should arrive at the GP soon after hospital discharge to ensure the quickest possible further treatment [4]. If letters are delivered weeks after the hospital stay, a continuous treatment of the patient cannot be ensured. Furthermore, the author of the medical discharge letter will no longer have current data after the discharge of the patient, which may result in a loss of important information [10]. Interfaces between different treatment areas and organizational units are known to cause a loss of information and a lack of quality in patient handling [11]. The improvement of information transfer between different healthcare providers during the transition of patients has been recommended to improve patient care [12, 13]. Delayed communication of findings may lead to a lack of continuity of care and suboptimal outcomes, as well as decreased satisfaction levels for both patients and GPs [14,15,16]. In a review of Kripalani et al., it was shown that 25% of discharge summaries were never received by GPs [17]. This has several negative consequences for patients. Li et al. [18] found that a delayed transmission or absence of the medical discharge summary is related to patient readmission, and a study by Gilmore-Bykovskyi [19] found a strong relationship between patients whose discharge summaries omitted designation of a responsible clinician/clinic for follow-up care and re-hospitalisation and/or death. A Swedish study by Carlsson et al. [20] points out that a lack of accuracy and continuity in discharge information on eating difficulties may increase risk of undernutrition and related complications. A study of Were et al. [18] investigated pending lab results in medical discharge summaries and found that only 16% of tests with pending results were mentioned in the discharge summaries, and Walz et al. [21] found that approximately one third of the sub-acute care patients had pending lab results at discharge, but only 11% of these were documented in the medical discharge summaries.

Quality, lack of information

Medical discharge letters are a key communication tool for patient safety issues [17]. Incomplete and insufficient medical discharge letters increase the risks of readmission and myriad other complications [22]. Langelaan et al. (2017) evaluated more than 2000 medical discharge letters and found that in about 60% of the letters essential information was missing, such as a change of the existing medication, laboratory data, and even data on the patients themselves [23]. Accurate and complete medical discharge summaries are essential for patient safety [17, 24, 25]. Addresses; patient data, including duration of stay; diagnoses; procedures; operations; epicrisis and therapy recommendations; as well as findings in the appendix; are minimum requirements that are supposed to be included in the medical discharge letter [4]. However, it was found that key components are often lacking in medical discharge letters, including information about follow-up and management plans [23, 26], test results [27,28,29], and medication adjustments [30,31,32,33,34,35]. In a review of Wimsett et al. [36] key components of a high-quality medical discharge summary were identified in 32 studies. These important components were discharge diagnosis, the received treatment, results of investigations as well as follow-up plans.

Accuracy of patients’ medication information is important to ensure patient safety. Hospital doctors expect GPs to continue with the prescribed (or modified) drug therapy. However, the selection of certain drugs is not always transparent for the GPs. A study by Grimes et al. [30] found that a discrepancy in medication documentation at discharge occurred in 10.8% of patients. From these patients nearly 65.5% were affected by discrepancies in medication documentation. The most prevalent inconsistency was drug omission (20.9%). Only 2% of patients were contacted, although general patient harm was assessed. A Swedish study of 2009 [37] investigated the quality improvement of medical discharge summaries. A higher quality of discharge letter led to an average of 45% fewer medication errors per patient.

A recent study by Tong et al. [38] revealed a reduced rate of medication errors in medical discharge summaries that were completed by a hospital pharmacist. Hospital pharmacists play a key role in preparing the discharge medication information transferred to GPs upon patient discharge and should work closely with hospital doctors to ensure accurate medication information that is quickly communicated to GPs at transitions of care [39]. Most hospitals have introduced electronic systems to improve the discharge communication, and many studies found a significant overall improvement in electronic transfer systems due to better documentation of information about follow-up care, pending test results, and information provided to patients and relatives [40,41,42]. Mehta et al. [43] found that the changeover to a new electronic system resulted in an increased completeness of discharge summaries from 60.7 to 75.0% and significant improvements in levels of completeness in certain categories.

Writing of medical discharge letter is missing in medical education

Both junior doctors as well as medical students reported that they received inadequate guidance and training on how to write medical discharge summaries [44, 45] and recognized that higher priority is often given to pressing clinical tasks [46]. Research into the causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors at hospitals in the UK has revealed that latent conditions like organizational processes, busy environments, and medical care for complex patients can lead to medication errors in the medical discharge summary [47].

Fortunately, some study results demonstrate that information and education on writing medical discharge letters would enhance communication to the GPs and prevent errors during the patient discharge process [37]. Minimal formal teaching about writing medical discharge summaries is common in most medical schools [39, 46]; however, a study by Shivji et al. has shown that simple, intensive educational sessions can lead to an improvement in the writing process of medical discharge summaries and communication with primary care [48].

Since the medical discharge letter should meet specific quality criteria, senior physicians and/or the head physician correct(s) and validate(s) the letter. The medical discharge letter therefore represents an essential learning target [8]. Training activities and workshops are necessary for junior doctors to improve writing medical discharge letters [44, 49]. It might be also useful for young doctors to use checklists or other structured procedures to improve writing [4]. Maher et al. showed that the use of a checklist enhanced the quality (content, structure, and clarity) of medical discharge letters written by medical students [50].

In the following Table 3 main risk factors of the medical discharge letter are summarized.

Discussion

The results of this systematic literature research indicate notable risk factors relating to the medical discharge letter. In a study by Sendlhofer et al., 360 risks were identified in hospital settings [51]. From these, 176 risks were scored as strategic and clustered into “top risks”. Top risks included medication errors, information errors, and lack of communication, among others. During this review, these potential risk factors were also identified in terms of the medical discharge letter.

Delayed sending and low quality of medical discharge letters to the referring physicians, may adversely affect the further course of treatment. However, a study of Spencer et al. has determined rates of failures in processing actions requested in hospital discharge summaries in general practice. It was found that requested medication changes were not made in 17% and patient harm occurred in 8% in relation to failures [52].

Despite the existence of reliable standards [53] many physicians are not adequately trained for writing medical discharge letters during their studies. Regular trainings and workshops and standardized checklists may optimize the quality of the medical discharge letter. Furthermore, electronic discharge letters have the potential to easily and quickly extract important information such as diagnoses, medication, and test results into a structured discharge document, and offer important advantages such as reliability, speed of information transfer, and standardization of content. Comprehensive discharge letters reduce the readmission rate and increase safety and quality by discharging of the patient. A missing structure, as well as a complex language, illegible handwriting, and unknown abbreviations, make reading medical discharge letters more complicated [4]. At least, poor patient understanding of their diagnosis and treatment plans and incomprehensible recommendations can adversely impact clinical outcome following hospital discharge. Many studies confirm that inadequate communication of findings [3, 39, 54] is an important risk factor in patients’ safety [51].

Most medical information in the discharge letter is not understood by patients (as well as relatives and other persons that are involved in the patients’ caring) and patients themselves do not receive a comprehensible medical discharge letter. The content of the medical discharge letter is often useless for the patient due to its medical terminology and content that is not matching with the patient’s level of knowledge or health literacy [55,56,57]. Poor understanding of diagnoses and related discharge plans are common among patients and family members and often accompanied by unplanned hospital readmissions [58,59,60,61]. In a study by Lin et al., it was shown that a patient-directed discharge letter enhanced understanding for hospitalization and for recommendations. Furthermore, verbal communication of the letter contents, explanation of every section of the medical discharge letter, and the opportunity for discussion and asking questions improved patient comprehension [7]. A study by O’Leary et al. showed that roughly 80–95% of patients with breast tumours want to be informed and educated about their illness, treatment, and prognosis [62].

High quality of care is characterized by a patient-centered communication, where the patient’s personal needs are also in focus [63]. Translation of medical terms in reports and letters leads to a better understanding of the disease and, interestingly, the avoidance of medical terms did not lead to deterioration in the transmission of information between the treating physicians. Moreover, it was found that the minimisation of medical terminology in medical discharge letters improved understanding and perception of patients’ ability to manage chronic health conditions [64]. In effect, it is clear that patient-centered communication improves outcome, mental health, patient satisfaction and reduces the use of health services [65].

Strengths and limitations

We have identified key problems with the medical discharge summaries that negatively impact patients’ safety and wellbeing. However, there is a heterogeneous nature of the included studies in terms of study design, sample size, outcomes, and language. Only two reviewers screened the studies for eligibility and only full-text articles were included in the literature review; furthermore, only the databases Pubmed and Cochrane library were screened for appropriate studies. Due to these constraints, there is a chance that other relevant studies may have been missed.

Conclusions

High-quality medical discharge letters are essential to ensure patient safety. To address this, the current review identified the major risk factors as delayed sending and low quality of medical discharge letters, lack of information and patient understanding, and inadequate training in writing medical discharge letters. In future, research studies should focus on improving the communication of pending test results and findings at discharge, and on evaluating the impact that this improved communication has on patient outcomes. Moreover, a simple patient-centered medical discharge letter may improve the patient’s (as well as family members’ and other caregivers’) understanding of disease, treatment and post-discharge recommendations.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Kreße B, Dinser R. Anforderungen an Arztberichte- ein haftungsrechtlicher Ansatz. Medizinrecht. 2010;28(6):396–400.

Möller K-H, Makoski K. Der Arztbrief - Rechtliche Rahmen- Bedingungen. 2015;5:186–94.

Van Walraven C, Weinberg AL. Quality assessment of a discharge summary system. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1437–42.

Unnewehr M, Schaaf B, Friederichs H. Die Kommunikation optimieren. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(37):831–4.

Roth-Isigkeit A, Harder S. Die Entlassungsmedikation im Arztbrief. Eine explorative Befragung von Hausärzten/−innen. Vol. 100, Medizinische Klinik. 2005. p. 87–93.

Bohnenkamp B. Arbeitsorganisation: Der Arztbrief - Viel mehr als nur lästige Pflicht. Vol. 113, Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2016. p. 2–4.

Lin R, Tofler G, Spinaze M, Dennis C, Clifton-Bligh R, Nojoumian H, Gallagher R, et al. Patient-directed discharge letter (PADDLE)-a simple and brief intervention to improve patient knowledge and understanding at time of hospital discharge. Hear Lung Circ. 2012;21:S312.

Hammerer P. Patientenverständliche Arztbriefe und Befunde. Springer Medizin. 2018;33(2):119–23.

Guise V, Anderson J, Wiig S. Patient safety risks associated with telecare: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):588.

Raab, A., & Drissner A. Einweiserbeziehungsmanagement: Wie Krankenhäuser erfolgreich Win-Win-Beziehungen zu niedergelassenen Ärzten aufbauen. Kohlhammer Verlag; 2011. 240 p.143.

Hart D. Vertrauen, Kooperation, Organisation. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2006. p. 845–7.

Cook RI. Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):791–4.

Duggan C, Feldman R, Hough J, Bates I. Reducing adverse prescribing discrepancies following hospital discharge. Int J Pharm Pract. 1998;6(2):77–82.

Polyzotis PA, Suskin N, Unsworth K, Reid RD, Jamnik V, Parsons C, et al. Primary care provider receipt of cardiac rehabilitation discharge summaries are they getting what they want to promote long-term risk reduction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):83–9.

Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson AS, Bates DW. “I wish i had seen this test result earlier!”: Dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Vol. 164, Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004. p. 2223–8.

Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: Challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Vol. 141, Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004. p. 533–6.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Were MC, Li X, Kesterson J, Cadwallader J, Asirwa C, Khan B, et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow-up providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1002–6.

Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Kennelty KA, Dugoff E, Kind AJH. Hospital discharge documentation of a designated clinician for follow-up care and 30-day outcomes in hip fracture and stroke patients discharged to sub-acute care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1).

Carlsson E, Ehnfors M, Eldh AC, Ehrenberg A. Accuracy and continuity in discharge information for patients with eating difficulties after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(1–2):21–31.

Walz SE, Smith M, Cox E, Sattin J, Kind AJH. Pending laboratory tests and the hospital discharge summary in patients discharged to sub-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):393–8.

Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, Chen C, Kanade S, Van Ness PH, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):436–43.

Alderton M, Callen JL. Are general practitioners satisfied with electronic discharge summaries? Vol. 36, Health Information Management Journal. 2007. p. 7–12.

Harel Z, Wald R, Perl J, Schwartz D, Bell CM. Evaluation of deficiencies in current discharge summaries for dialysis patients in Canada. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:77–84.

Philibert I, Barach P. The European HANDOVER Project: A multi-nation program to improve transitions at the primary care - Inpatient interface. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21(SUPPL. 1).

Greer RC, Liu Y, Crews DC, Jaar BG, Rabb H, Boulware LE. Hospital discharge communications during care transitions for patients with acute kidney injury: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:449.

Belleli E, Naccarella L, Pirotta M. Communication at the interface between hospitals and primary care: a general practice audit of hospital discharge summaries. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(12):886–90.

Roy CL, Poon EC, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–8.

Gandara E, Moniz T, Ungar J, Lee J, Chan-Macrae M, O’Malley T, et al. Communication and information deficits in patients discharged to rehabilitation facilities: an evaluation of five acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E28–33.

Grimes T, Delaney T, Duggan C, Kelly JG, Graham IM. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharge: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir J Med Sci. 2008;177(2):93–7.

Uitvlugt EB, Siegert CEH, Janssen MJA, Nijpels G, Karapinar-Çarkit F. Completeness of medication-related information in discharge letters and post-discharge general practitioner overviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1206–12.

Ooi CE, Rofe O, Vienet M, Elliott RA. Improving communication of medication changes using a pharmacist-prepared discharge medication management summary. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(2):394–402.

Perren A, Previsdomini M, Cerutti B, Soldini D, Donghi D, Marone C. Omitted and unjustified medications in the discharge summary. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18(3):205–8.

Garcia BH, Djønne BS, Skjold F, Mellingen EM, Aag TI. Quality of medication information in discharge summaries from hospitals: an audit of electronic patient records. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(6):1331–7.

Monfort AS, Curatolo N, Begue T, Rieutord A, Roy S. Medication at discharge in an orthopaedic surgical ward: quality of information transmission and implementation of a medication reconciliation form. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):838–47.

Wimsett J, Harper A, Jones P. Review article: Components of a good quality discharge summary: A systematic review. Vol. 26, EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2014. p. 430–8.

Bergkvist A, Midlöv P, Höglund P, Larsson L, Bondesson Å, Eriksson T. Improved quality in the hospital discharge summary reduces medication errors-LIMM: Landskrona integrated medicines management. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):1037–46.

Tong EY, Roman CP, Mitra B, Yip GS, Gibbs H, Newnham HH, et al. Reducing medication errors in hospital discharge summaries: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2017;206(1):36–9.

Yemm R, Bhattacharya D, Wright D, Poland F. What constitutes a high quality discharge summary? A comparison between the views of secondary and primary care doctors. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:125–31.

O’Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, Liss DT, Evans DB, Kulkarni N, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):219–25.

Chan S. P Maurice a, W pollard C, Ayre SJ, Walters DL, Ward HE. Improving the efficiency of discharge summary completion by linking to preexisiting patient information databases. BMJ Qual Improv Reports. 2014;3(1):1–5.

Lehnbom EC, Raban MZ, Walter SR, Richardson K, Westbrook JI. Do electronic discharge summaries contain more complete medication information? A retrospective analysis of paper versus electronic discharge summaries. Heal Inf Manag J. 2014;43(3):4–12.

Mehta RL, Baxendale B, Roth K, Caswell V, Le Jeune I, Hawkins J, et al. Assessing the impact of the introduction of an electronic hospital discharge system on the completeness and timeliness of discharge communication: A before and after study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1).

Heaton A, Webb DJ, Maxwell SRJ. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: the views of 2413 UK medical students and recent graduates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):128–34.

Maxwell S, Walley T. Teaching safe and effective prescribing in UK medical schools: A core curriculum for tomorrow’s doctors. Vol. 55, British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2003. p. 496–503.

Frain JP, Frain AE, Carr PH. Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries. Br Med J. 1996;312(7027):350.

Dornan T, Investigator P, Ashcroft D, Lewis P, Miles J, Taylor D, et al. An in depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. EQUIP study. Vol. 44, Methods. 2010.

Shivji FS, Ramoutar DN, Bailey C, Hunter JB. Improving communication with primary care to ensure patient safety post-hospital discharge. Br J Hosp Med. 2015;76(1):46–9.

Cresswell A, Hart M, Suchanek O, Young T, Leaver L, Hibbs S. Mind the gap: Improving discharge communication between secondary and primary care. BMJ Qual Improv Reports. 2015;4(1):u207936.w3197.

Maher B, Drachsler H, Kalz M, Hoare C, Sorensen H, Lezcano L, et al. Use of Mobile applications for hospital discharge letters - improving handover at point of practice. Int J Mob Blended Learn. 2013;5(4):29.

Sendlhofer G, Brunner G, Tax C, Falzberger G, Smolle J, Leitgeb K, et al. Systematic implementation of clinical risk management in a large university hospital: the impact of risk managers. Wien Klin Wochenschr [Internet]. 2015; 127:1–11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-014-0620-7

Spencer RA, Spencer SEF, Rodgers S, Campbell SM, Avery AJ. Processing of discharge summaries in general practice: a retrospective record review. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(673):e576–85.

Carpenter I. A Clinician’s guide to record standards - part 2: standards for the structure and content of medical records and communications when patients are admitted to hospital. Acad Med R Coll R Coll Physicians. 2008;10(5):24.

GMC. Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices. Good Medical Practice. 2013. p. 1–11.

Jolly BT, Scott JL, Sanford SM. Simplification of emergency department discharge instructions improves patient comprehension. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(4):443–6.

Williams DM, Counselman FL, Caggiano CD. Emergency department discharge instructions and patient literacy: a problem of disparity. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(1):19–22.

Jolly BT, Scott JL, Feied CF, Sanford SM. Functional illiteracy among emergency department patients: a preliminary study. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(3):573–8.

Soler RS, Juvinyà Canal D, Noguer CB, Poch CG, Brugada Motge N, Garcia D m, Gil M. Continuity of care and monitoring pain after discharge: patient perspective. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(1):40–8.

Grover G, Berkowitz CD, Lewis RJ. Parental recall after a visit to the emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994;33(4):194–201.

Witherington EMA, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2008;17(1):71–5.

Marcantonio ER, McKean S, Goldfinger M, Kleefield S, Yurkofsky M, Brennan T. a. Factors associated with unplanned hospital readmission among patients 65 years of age and older in a Medicare managed care plan. Am J Med. 1999;107(1):13–7.

O’Leary KA, Estabrooks CA, Olson K, Cumming C. Information acquisition for women facing surgical treatment for breast cancer: Influencing factors and selected outcomes. Vol. 69, Patient Education and Counseling. 2007. p. 5–19.

Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Bengel J. Arzt-Patienten-Kommunikation in der Tumorbehandlung: Erwartungen und Erfahrungen aus Patientensicht. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Psychol. 2006;15(4):149–61.

Wernick M, Hale P, Anticich N, Busch S, Merriman L, King B, et al. A randomised crossover trial of minimising medical terminology in secondary care correspondence in patients with chronic health conditions: impact on understanding and patient reported outcomes. Intern Med J. 2016;46(5):596–601.

Woods SS, Schwartz E, Tuepker A, Press NA, Nazi KM, Turvey CL, et al. Patient experiences with full electronic access to health records and clinical notes through the my healthevet personal health record pilot: Qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;(15, 3).

Weiskopf NG, Rusanov A, Weng C. Sick patients have more data: the non-random completeness of electronic health records. MIA Symp. 2013;2013:1472–7.

Choudhry AJ, Baghdadi YMK, Wagie AE, Habermann EB, Heller SF, Jenkins DH, et al. Readability of discharge summaries: with what level of information are we dismissing our patients? In: Am J Surg. 2016. p. 631–6.

Li JYZ, Yong TY, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH. Timeliness in discharge summary dissemination is associated with patients’ clinical outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(1):76–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research project was part of a project funded by the Gesundheitsfonds Steiermark. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS wrote the manuscript; CS, MH and PS performed the literature search; LK contributed to the conception of this work; GB contributed to the interpretation of data and GS supervised the project. All authors were critically revising the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwarz, C.M., Hoffmann, M., Schwarz, P. et al. A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis on the risks of medical discharge letters for patients’ safety. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 158 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3989-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3989-1